Introduction

Up to three million healthcare workers (HCW) are exposed to body fluid and resulting bloodborne pathogens each year, causing more than 170 000 HIV infections, two million viral hepatitis B (HBV) and 0,9 million viral hepatitis C (HCV) [

1]. Some of these infections result from poor compliance with standard precautions while providing health services [

1,

2].

The implementation of standard precautions within healthcare facilities aim to curve the transmission of infections. Standard precautions include administrative aspects of infection control measures, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), engineering and environmental measures [

4]. Insufficient adherence to standard precautions have been linked to poor supply of PPE and factors related to work environment [

5]. Several institutional and healthcare workers related factors affect compliance with standard precautions, especially in resource limited countries [

6]. Low compliance with adequate precautions leads to high vulnerability of HCW. All categories of health facilities are affected, including reference hospitals where a high prevalence of accidental exposure to body fluids and poor coverage with required vaccines has been reported among HCW [

7]. Splashes occur frequently among midwives and nurses where they involve mucous membranes or skin breaches [

8,

9]. Most of such accidental exposures occur during childbirth, in surgical room during pulsatile lavage [

10,

11]. It is also frequently observed in almost every manual cleaning activity especially those involving running the faucet and rinsing soiled medical devices [

12,

13]. Interest in the control and prevention of infections in healthcare settings has been renewed with the advent of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome due to Corona Virus (COVID – 19) and its inclusion in the list of diseases transmitted by contaminated expectorations [

14]. HCW are four times greater risk of contracting HBV and COVID-19 infections than the general population [

15]. Vaccination is the most cost-efficient intervention for transmissible diseases prevention. In preventing healthcare associated infections, many countries recommend that HCW receive shots against influenza, hepatitis B, pertussis, measles, rubella, mumps, varicella, tetanus, diphtheria and COVID-19 [

16]. Vaccine administration aims to stimulate host immunity. Vaccines are typically whole virus, protein subunit, viral vector or pathogen nucleic acid [15-16]. Even though HCW are considered a priority intervention group for COVID-19 vaccination, unconfirmed reports indicated vaccine hesitancy as a barrier to its uptake [

18].

The present study aimed to assess the level of implementation of infection control measures in reference health facilities, inclusive of compliance with vaccination during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Methods

Study design & period: We conducted an institutional-based cross-sectional study in the six district hospitals of Yaounde from January to April, 2022.

Setting: The Cameroonian health system is organised around health districts. The district hospital is the first level of reference in the health pyramid. It is responsible for providing primary health cares to the population [

19]. The Yaounde DHs (Biyem Assi, Cite Verte, Djoungolo, Efoulan, Mvog Ada and Nkolndongo) cover a population of 3.2 million residents, cumulate nearly 400 health personnel, 330 beds, 153 583 consultations with 19 092 hospital admission per annum [

20,

21].

Participant: The study population consisted of workers who are in contact with patients and potentially exposed to body fluids. They were medical (physician and intern), paramedics (nurse, assistant nurse, midwife, laboratory and dental technician) and hygiene (cleaners, hygiene and sanitation engineer).

Sample size: The sample size was calculated using the single proportion formula (n = [Zα / 2]

2 *[P (1-P)]/ E

2) at 95% confidence interval, where Zα / 2 = 1.96 and P = 36,7 % was obtained from a similar study in referral hospital in Yaounde [

22]. The standard error was E = 5 %. Using above formula, we obtained 357 + 36 (10% dropouts) = 393 as our sample size. Since our exact population of respondents was less than 10 000, we used correction formula (nf = [ni / (1 + ni / N)] , where nf = minimum required sample size, ni = reduced sample size and N = total number of our respondents [

23]. Using correction formula [393 / (1 + 393 / 400)], a minimum required sample size of 198 was obtained. An exhaustive sampling method was adopted in each clinical department and all consenting personnel included.

Data collection: The study instrument was an anonymous, structured and self – administered questionnaire consisting of 20 questions on demographics (age, gender, occupation, length of employment), compliance with standard precautions, AEB experience, appreciation of PPE availability and vaccination status.

Data processing and analysis: All filled questionnaires were entered and analysed using R statistics Version 4.2.3. The Chi-square (X2) test or Fisher's exact test for proportions were used to compare proportions. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to assess the strength of the association between variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Out of the 279 healthcare workers who were contacted, 217 returned the completed questionnaire, representing a response rate of 78 %.

Most of study participants were female (81%). Participants aged 25-34 (38.2%) were the most represented. Almost half of the participants were married (54.8%). Participants were mainly nurses (32.3%) and laboratory technicians (21.2%). Half of the health personnel had a professional experience of 3 to 7 years of professional experience (Table II).

Reported observance of universal precautions

A third of the participants (30 %) stated that they placed used syringes temporarily on benches and trolleys. Nearly a quarter of the participants (17 %) reported washing the scalpel blades for reuse and the highest proportion was found among medical personnel (9.2 %) (p-value < 0.0001) (Table I).

Table I.

Selected Practices related to Universal Precautions among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n=217)

Table I.

Selected Practices related to Universal Precautions among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n=217)

| Variable |

Professional group n (%) |

Total |

p-value |

Precaution activity

|

Medical

n = 34 |

Paramedics

n = 163 |

Hygiene

n = 20 |

|

|

| Needle recapping |

28 (82.4) |

107 (65.6) |

11 (55) |

146 (67.3) |

0.077(1)

|

| Temporal staging of used needles on bench |

12 (35.3) |

53 (32.5) |

0 |

65 (30.0) |

0.008(1)

|

| Wash of scalpel for reuse |

1 (3.0) |

15 (9.2) |

1 (5) |

17 (8.5) |

<0.0001(2)

|

| Facilities used for sharps disposal |

|

|

|

|

|

| Safety box |

33 (97.0) |

159 (97.5) |

19 (95) |

211(97.3) |

|

| Plastic bottle |

0 |

4 (2.5) |

0 |

4 (1.8) |

0.213(2)

|

| Trash can |

1 (3.0) |

0 |

1 (5) |

2 (0.9) |

|

Hand washing

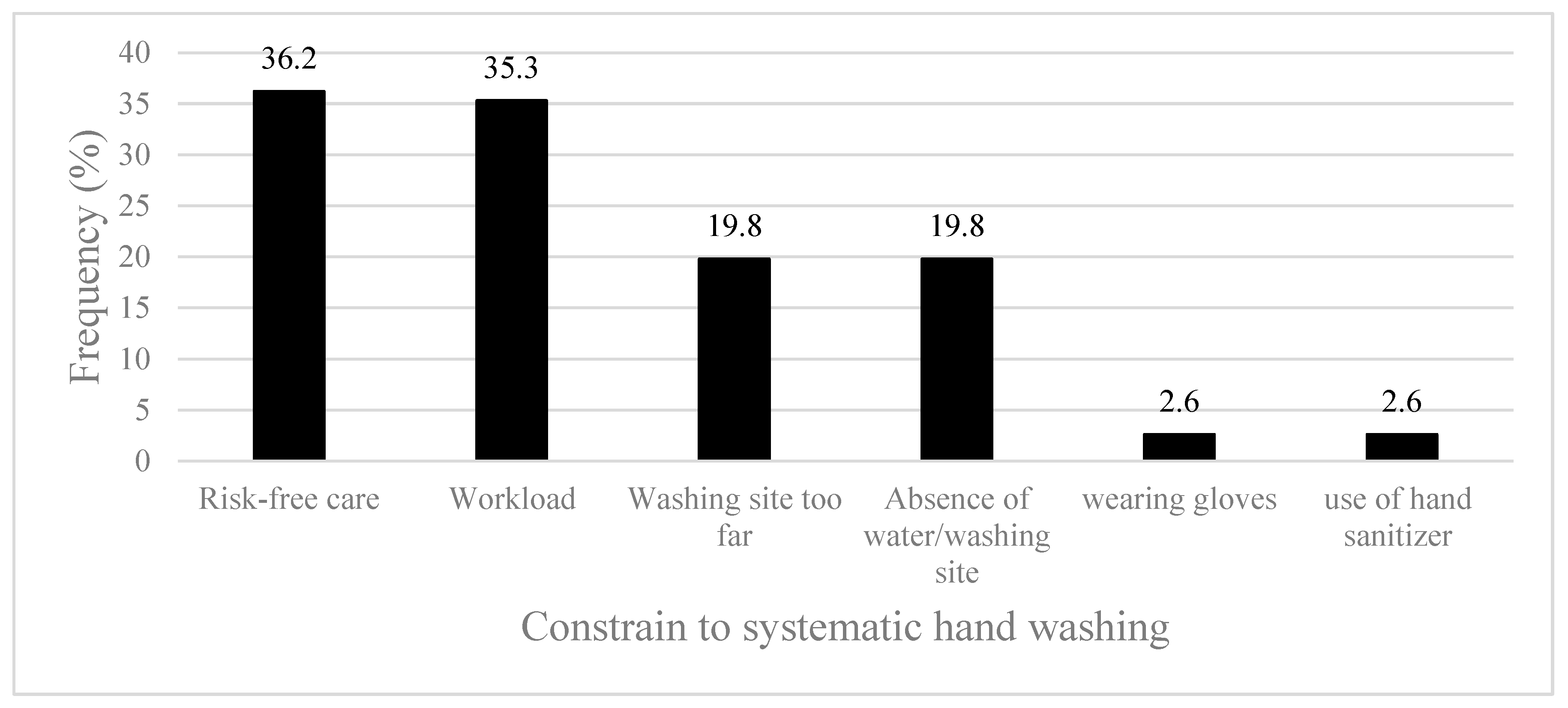

More than half of the participants (53.5 %) reported not systematically washing their hand after each care. Such was attributed mainly to the perception that the patient care for was risk free (36 %), high workload (35 %) and the proximity of the point of care to the running water washing point (20 %) (

Figure 1).

Accidental exposure to blood

Over the last 12 months, almost half of HCW (46.5 %; CI: 39.8 – 53.4 %) experienced a splash exposure. (Additional information on needle stick exposure are available through the link:

https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100321)

Mvog Ada DH (60 %) had the highest prevalence of exposure to splashes. The difference was however non-significant (p-value = 0.057) (Table I).

Table I.

Experience of Training on Infection Prevention and splashes among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n = 217)

Table I.

Experience of Training on Infection Prevention and splashes among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n = 217)

| Health facility |

Training on IC |

p – value (1)

|

splash ≤ 12 months |

|

p-value(1)

|

| |

n (%) |

|

n (%) |

95 % CI Limit |

Total |

|

| |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

|

| Biyem Assi |

20 (51) |

|

12(33.3) |

18.6 |

51.0 |

39 |

0.057 |

| Cite Verte |

21 (49) |

|

12 (30.8) |

17.0 |

47.6 |

43 |

| Djoungolo |

10 (26) |

0.337 |

21 (48.8) |

33.3 |

64.5 |

38 |

| Efoulan |

1 (3) |

|

21 (55.3) |

38.3 |

71.4 |

30 |

| Mvog Ada |

13 (42) |

|

18 (60) |

40.6 |

77.3 |

31 |

| Nkolndongo |

15 (42) |

|

17 (54.8) |

36.0 |

72.7 |

36 |

| Total |

80 (37) |

|

101 (46.5) |

39.8 |

53.4 |

217 |

|

Participants that reported splashes were midwifes/birth attendants (71.4 %). Surface workers were the least exposed (5.6 %). The difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.002). Most of projections were observed in the surgical (64.7 %), obstetrics & gynaecology (64.5 %) and stomatology departments (61.1 %). The difference was significant (p-value <0.0001) (Table II).

Table II.

Socio-professional determinants among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospital, April 2022 (n = 217).

Table II.

Socio-professional determinants among healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospital, April 2022 (n = 217).

| Characteristic |

Count (n) |

Frequency (%) |

Total (100 %) |

p-value |

| Gender |

|

|

|

0.055(1)

|

| Female |

87 |

49.4 |

176 |

| Male |

14 |

34.1 |

41 |

| Age |

|

|

|

|

| 18 - 24 |

5 |

29.4 |

17 |

0.122(2)

|

| 25 - 34 |

46 |

55.4 |

83 |

| 35 - 44 |

33 |

42.9 |

77 |

| 45 - 49 |

8 |

33.3 |

24 |

| 50 + |

9 |

56.2 |

16 |

| Professional grade |

|

|

|

|

| Assistant nurse |

8 |

44.4 |

18 |

|

| Student |

6 |

50.0 |

12 |

|

| Nurse |

39 |

44.3 |

70 |

|

| Sanitary engineer |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.002(2)

|

| Doctor |

18 |

48.6 |

37 |

|

| Cleaner |

1 |

5.6 |

18 |

|

| Midwife/Birth attendant |

10 |

71.4 |

14 |

|

| Laboratory & dental technician |

19 |

41.3 |

46 |

|

| Unit |

|

|

|

|

| Surgery |

22 |

64.7 |

34 |

|

| Hygiene and sanitation |

1 |

5 |

20 |

|

| Laboratory |

21 |

41.2 |

51 |

|

| Obstetrics & gynaecology |

20 |

64.5 |

31 |

<0.0001(2)

|

| Medicine |

14 |

37.2 |

37 |

|

| Stomatology |

11 |

61.1 |

18 |

|

| Paediatrics |

12 |

46.2 |

26 |

|

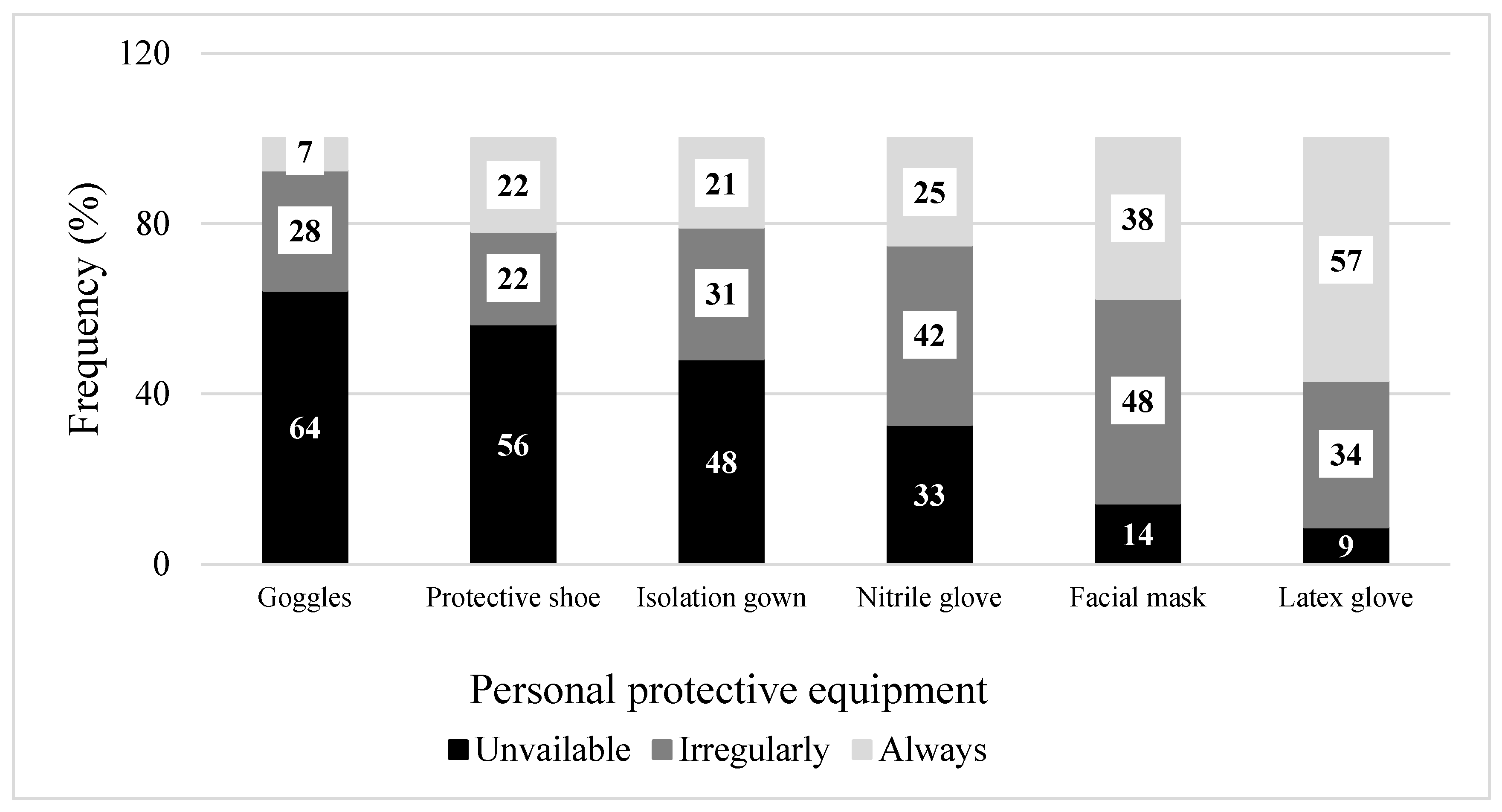

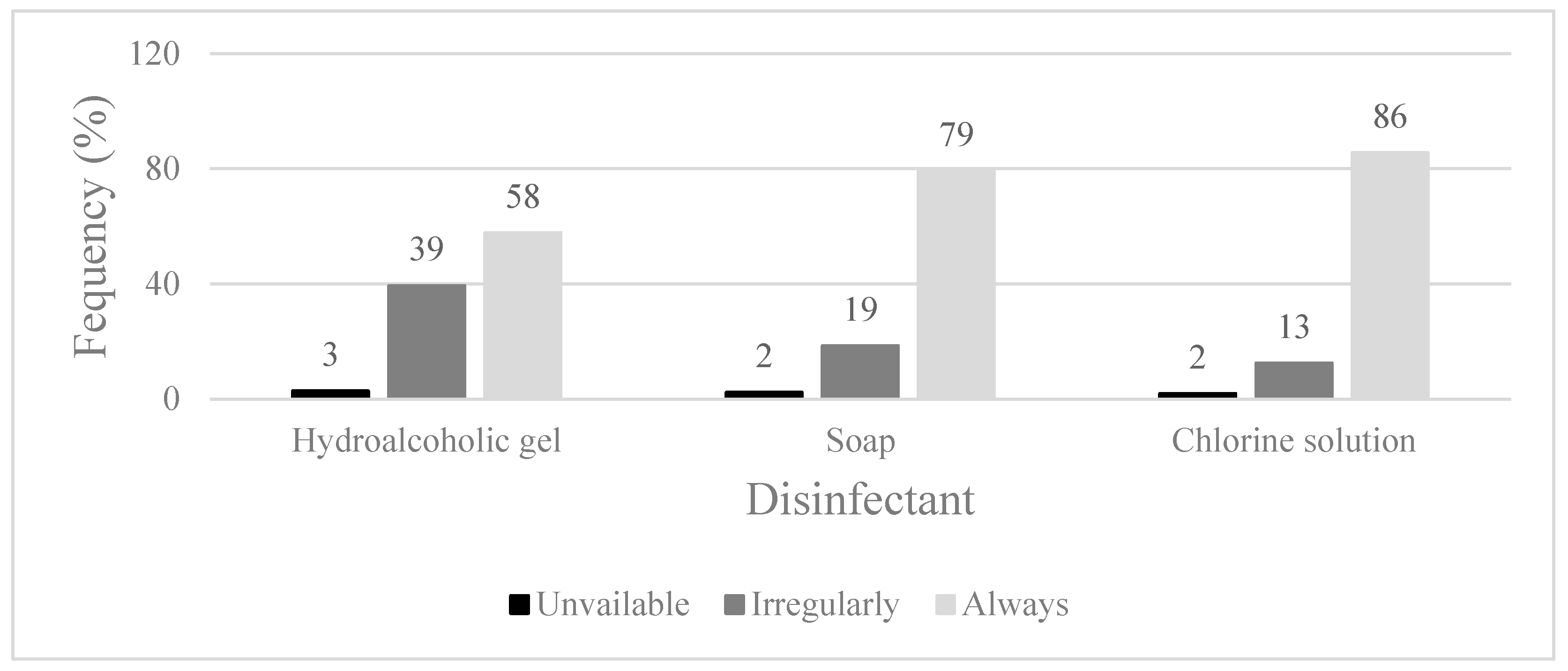

Personal protective equipment (PPE) and hygiene

HCW reported that PPE was always available for use (43 %). Goggles/visors/face shields, protective shoes and gowns were the least accessible PPE. Face masks and sterile gloves were inconsistently accessible (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Djoungolo, Mvog Ada and Nkoldongo District Hospitals reported a considerable deficit in infection control inputs. The obstetrics and stomatology departments reported the least PPE supplies.

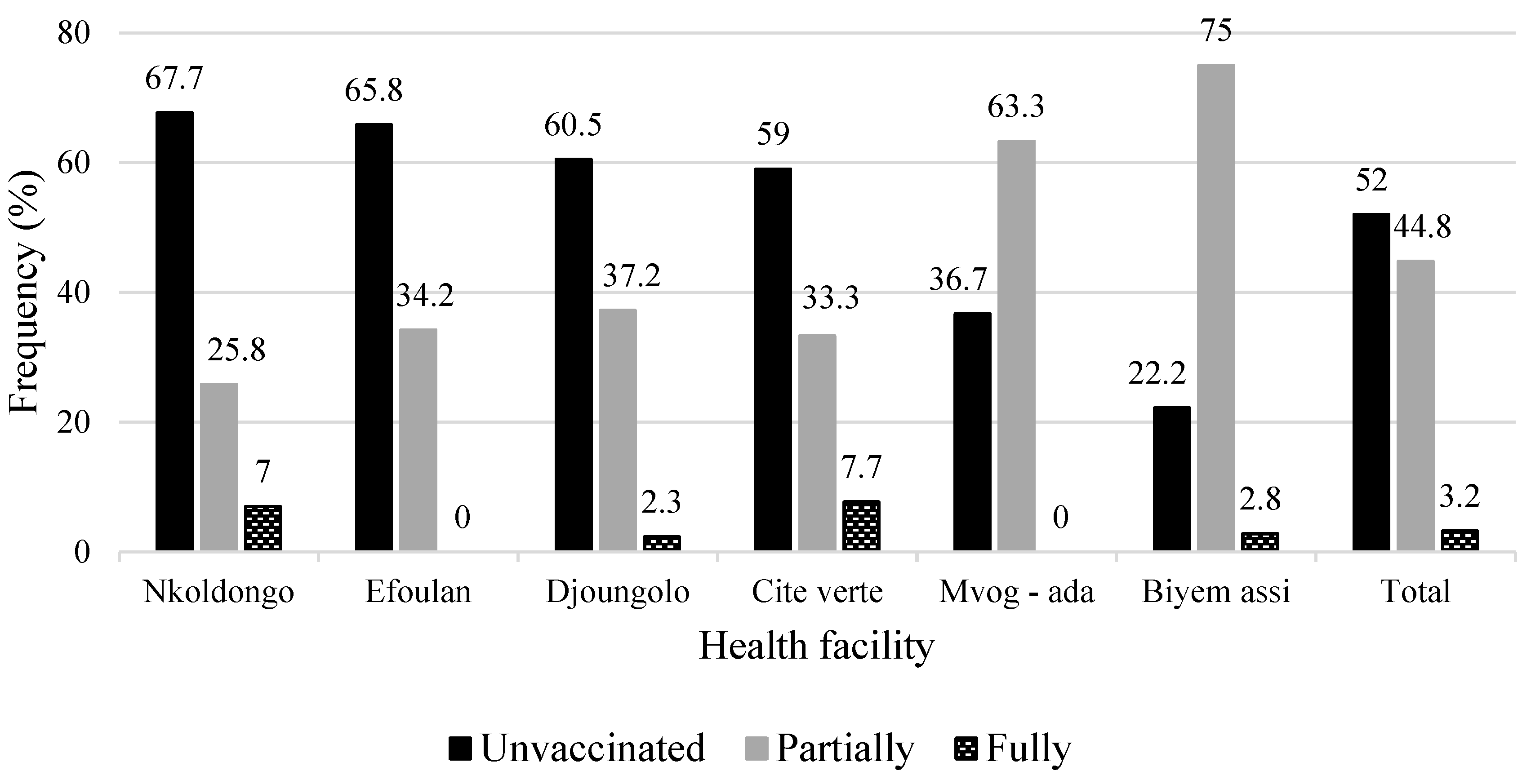

COVID-19 vaccination coverage

Less than half of participants had received a course of COVID-19 vaccine (44.8 %). Nkolndongo (74.2 %) and Cite Verte (66.7 %) had the highest of non-immunized (

p-value <0.0001) (

Figure 4).

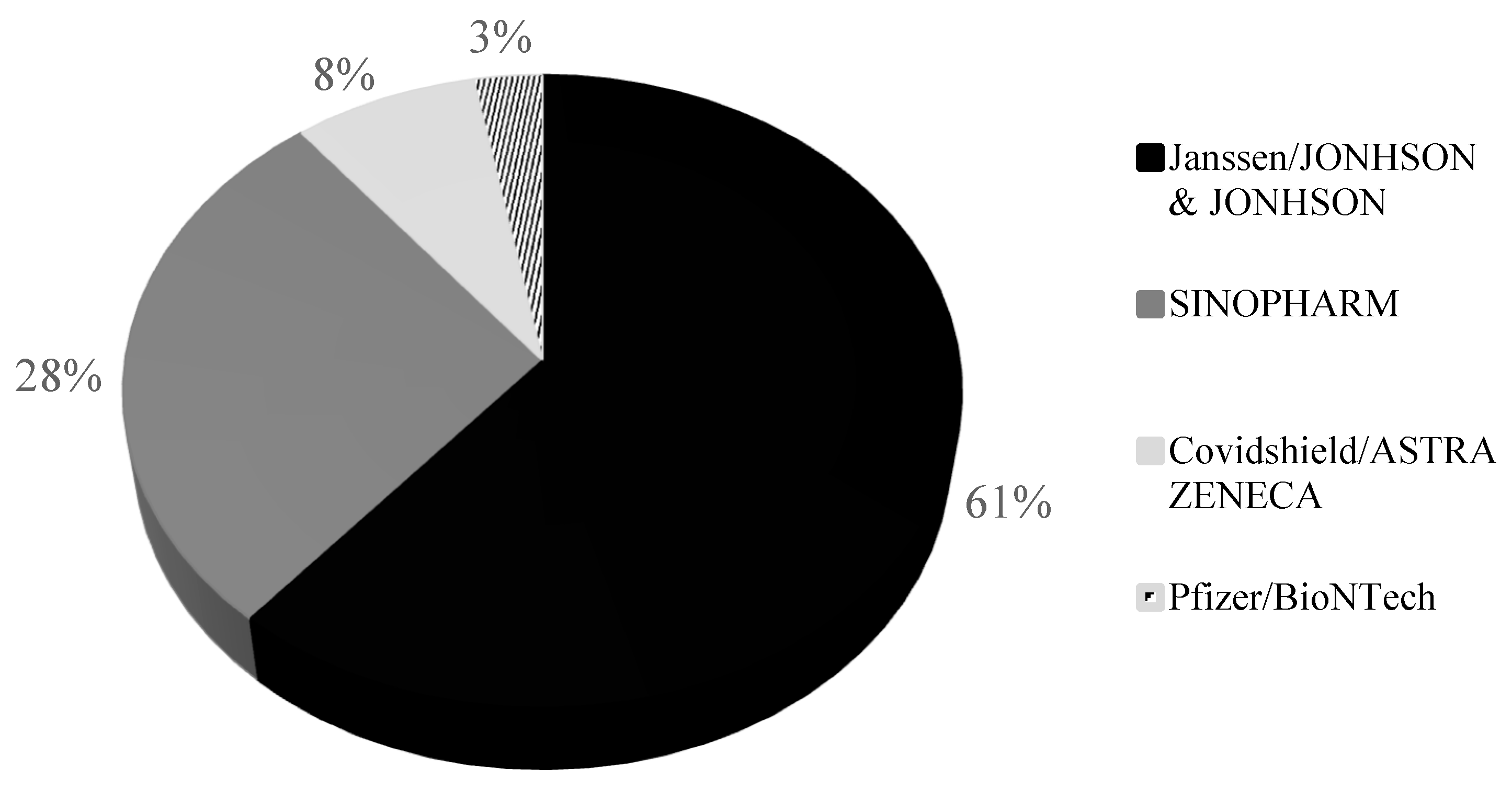

The vaccine most preferred by HWC were Janssen (61 %) and Sinopharm (28 %). Astra Zeneca and Pfizer were the least administered (

Figure 5).

Most of non-fully immunized healthcare workers were medical (61.8 %) and paramedical (52.1 %) professionals. (Table III).

Table III.

COVID – 19 vaccination status and socio - professional status of healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospital, April 2022 (n = 217).

Table III.

COVID – 19 vaccination status and socio - professional status of healthcare workers in Yaounde district hospital, April 2022 (n = 217).

| Professional status |

Vaccination status n (%) |

Total |

p-value(1)

|

| |

Unvaccinated |

Partially |

Fully |

|

|

| Medical |

21 (61.8) |

0 |

13 (38.2) |

34 (100) |

|

| Paramedics |

85 (52.1) |

7 (4.3) |

71 (43.6) |

163 (100) |

0.42 |

| Hygiene |

8 (40.0) |

0 |

12 (60) |

20 (100) |

|

Being a non-doctor or civil servant were among the protective factors (Table IV).

Table IV.

Factors associated with unacceptance of COVID – 19 vaccinations among health staff in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n = 217).

Table IV.

Factors associated with unacceptance of COVID – 19 vaccinations among health staff in Yaounde district hospitals, April 2022 (n = 217).

| Factor |

aOR |

95% CI |

| |

|

Lower |

Upper |

| Male/Female |

0.90 |

0.45 |

1.81 |

| Single/Married |

1.16 |

0.66 |

2.03 |

| Educational level: < 12 years/≥ 12 years |

1.50 |

0.68 |

3.34 |

| Other working group/Doctors |

0.65 |

0.30 |

1.43 |

| Civil servant/Contractual |

0.73 |

0.40 |

1.31 |

| Infection control training: No/Yes |

0.97 |

0.55 |

1.71 |

| aOR : adjusted Odds Ratio |

|

|

|

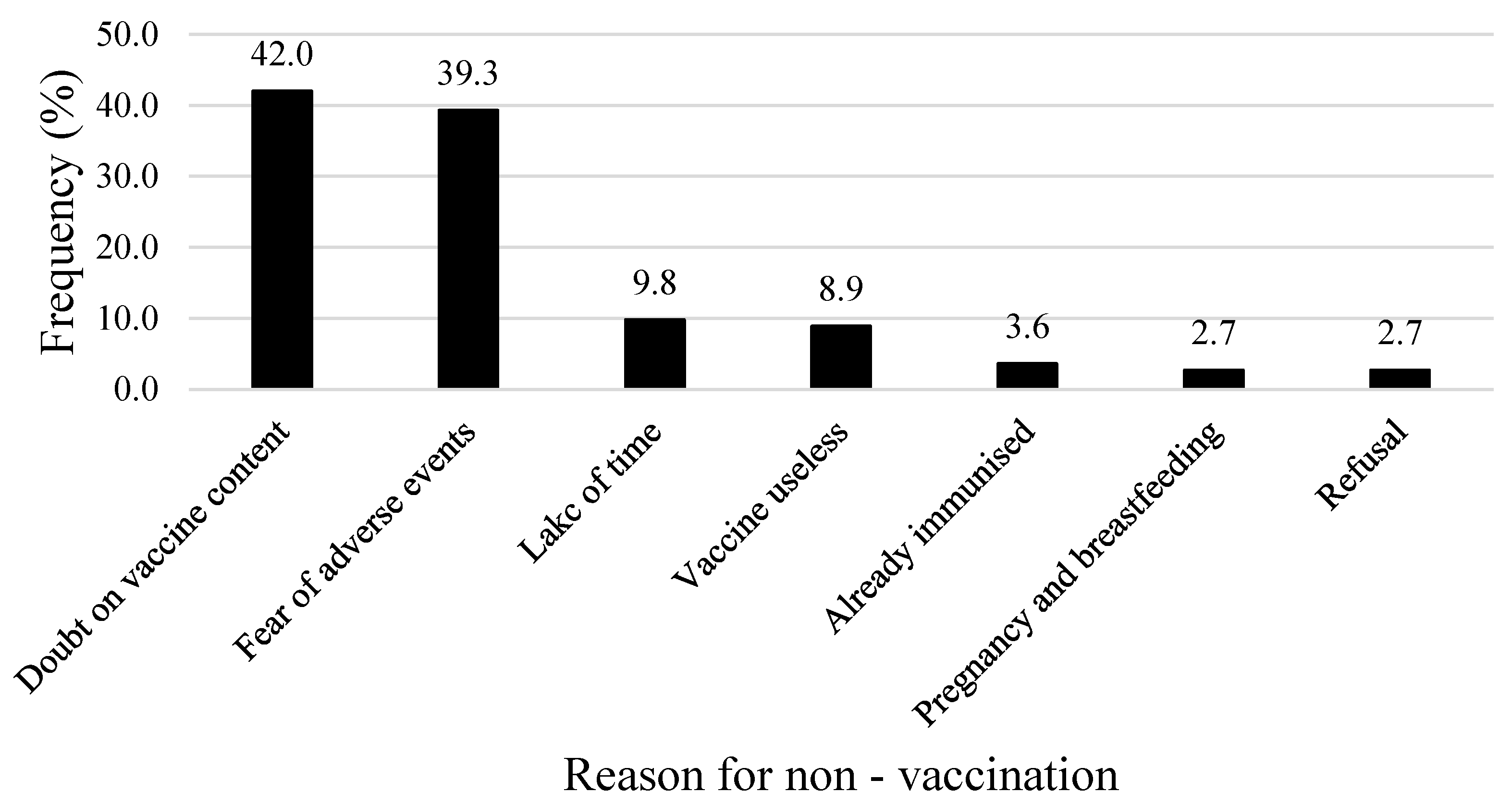

The main reasons of non-vaccination against COVID-19 were doubt on the content of the vaccines (42 %) and fear of side effects (39.3 %) (

Figure 6).

Discussion

More than two third of respondents recap needles during healthcare activities. This proportion is higher than that found in Congo and Morocco [

22,

23]. Nearly a third of respondents reported poor used needle disposal practices. Nearly 10 % of respondent claimed to wash the scalpel blades for reuse, a practice that increases the risk of percutaneous exposure to blood. Non-compliance with universal precautions was higher among paramedics.

The fact that half of staff did not systematically wash their hands after health services is worrisome. This practice is higher than those reported elsewhere in Africa [

24,

25]. Healthcare workers attributed this poor performance to contextual difference including high workload and unavailability of water or washing facilities far from the point of care. Mandana and Likwela in DRC reported urgency as the main reasons for non-compliance with this standard precaution [

24]. Sub – optimal adherence to universal precautions may reflect insufficient supervision of health facilities and their staff by intermediate or central level public health authorities. In developed countries these measures are enforced in health facilities by an infection control committee. Internal and external monitoring and supervision ensure compliance with defined guidelines [

26].

Midwives and nurses were the most affected by splashes confirming observations in other settings in France and Ivory – coast [

10,

25].

PPE were inconsistently available for use (43,6 %). This corroborates studies in Yemen (46.3 %) [

28]. Higher availability were observed in Nigeria (67.2 %) [

29].

Goggles/facial shields, protective shoes and gowns were the least accessible PPE while face masks and sterile gloves were inconsistently accessible. Departments most affected by lack of PPE included obstetrics & gynaecology and stomatology. Under resources constrains, it was expected that surgery department was given precedence as invasive procedures are carried out. [

30]. Such misconceptions and erroneous perception should be cleared.

Nevertheless, some of these inputs (care/sterile gloves) were made available to the care provider by patients, which explain the fact that most of healthcare workers did not express the shortage. Non-systematic use of these devices by healthcare providers exposes them to the risk of HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses contaminations etc [

26,

29].

Almost half of healthcare personnel (52 %) were unvaccinated for COVID-19. Vaccination against COVID-19 has experienced great media coverage both nationally and internationally. District Hospitals have put in place incentive procedures such as the availability of daily vaccination centres. The cost free vaccine has also facilitated access at a time (April 2022) when coverage of fully vaccinated people was still very low (4.4 – 4.6 %) [

31,

32].

The Janssen vaccine was the most requested vaccine (61 %), consistent with the national trend [

18]. Its unique dose regimen has largely contributed to its appropriation by healthcare workers.

The fact that medical (61.8 %) and paramedics (56.4 %) professionals were more reluctant to vaccination is staggering. This could be due to doubts about the content of the vaccine (42 %) and fear of vaccine-related side effects (39.3 %). Indeed, people with doubts about vaccine content had a 91 % chance of not accepting the COVID-19 vaccine [

33].

Controversies that aroused by the COVID-19 vaccine in social media regarding efficacy and safety, would have fuelled the poor adherence and vaccine hesitancy among health staff who belong to this virtual community. In this regard, vaccine hesitancy was described as one of the barriers to vaccination [

33].

Conclusion

Splash exposure was common among healthcare workers. PPE availability remained a challenge for most of health facilities despite the request of guidelines in COVID-19 pandemic context. More institutional strategies should be implemented to tackle occupational infection related to splashes. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among health personnel remains insufficient to ensure adequate protection. Communication on COVID-19 vaccine safety will be a useful tool against vaccine hesitancy.

Author's Contribution

Drafting of the study protocol, data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafting and editing of manuscript: F.Z.L.C.; Critical revision of protocol, critical revision of manuscript: E.E.L., J.H.N., and M-K.F-X.; Conception, design and supervision of research protocol and implementation, data analysis plan, revision, editing and final validation of the manuscript: I.T.

Funding Source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Approval Statement

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Regional Human Health Committee of the Centre (CRERSH - Ce) and the ethical clearance: CE N° 2245/CRERSHC/2021 issued.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to the health personnel who agreed to participate in this study and to the managers of the health facilities who gave their authorisation for the conduct of this study.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest and have approved the final article.

References

- Westermann, C.; Peters, C.; Lisiak, B.; Lamberti, M.; Nienhaus, A. The prevalence of hepatitis C among healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 72, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Aide-memoire for a strategy to protect health workers from infection with bloodborne viruses [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2003 [cited 2021 Sep 8]. Report No.: WHO/BCT/03.11. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/68354.

- Annette PU, Elisabetta R, Yvan H. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med [Internet]. 2005 Dec [cited 2021 Sep 8];48(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16299710/.

- Infection Prevention and Control of Epidemic- and Pandemic-Prone Acute Respiratory Infections in Health Care [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 [cited 2023 Jun 28]. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK214359/.

- Motaarefi H, Mahmoudi H, Mohammadi E, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A. Factors Associated with Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Occupations: A Systematic Review. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2016 Aug;10(8):IE01–4.

- Gumodoka, B.; Favot, I.; A Berege, Z.; Dolmans, W.M. Occupational exposure to the risk of HIV infection among health care workers in Mwanza Region, United Republic of Tanzania. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 1997, 75, 133–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cheuyem, F.Z.L.; Lyonga, E.E.; Kamga, H.G.; Mbopi-Keou, F.-X.; Takougang, I. Needlestick and Sharp Injuries and Hepatitis B Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Cross Sectional Study in Six District Hospitals in Yaounde (Cameroon). J. Community Med. Public Heal. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene T, Tadesse S. Predictors of occupational exposure to HIV infection among healthcare workers in southern Ethiopia. 2014;10(i3).

- Em B, It W, Cn S, Me C. Risk and management of blood-borne infections in health care workers. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2000 Jul [cited 2021 Sep 8];13(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10885983/.

- Ward, C.L.; Kozian, L.; Bartolacci, J.; Krupp, J.C.; Karadsheh, M.J.; Weiss, E.S.; Patel, S.A.M. A Novel Approach to Reducing Splash Exposure in Pulsatile Lavage. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. - Glob. Open 2023, 11, e5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent A, Cohen M, Bernet C, Parneix P, L’Hériteau F, Branger B, et al. [Accidental exposure to blood by midwives in French maternity units: results of the national surveillance 2003]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2006 May;35(3):247–56.

- Shitu, S.; Adugna, G.; Abebe, H. Occupational exposure to blood/body fluid splash and its predictors among midwives working in public health institutions at Addis Ababa city Ethiopia, 2020. Institution-based cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0251815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofstead, C.L.; Hopkins, K.M.; Daniels, F.E.; Smart, A.G.; Wetzler, H.P. Splash generation and droplet dispersal in a well-designed, centralized high-level disinfection unit. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2022, 50, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagoe-Moses, C.; Pearson, R.D.; Perry, J.; Jagger, J. Risks to Health Care Workers in Developing Countries. New Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziraba, A.K.; Bwogi, J.; Namale, A.; Wainaina, C.W.; Mayanja-Kizza, H. Sero-prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 191–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haviari, S.; Bénet, T.; Saadatian-Elahi, M.; André, P.; Loulergue, P.; Vanhems, P. Vaccination of healthcare workers: A review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 2522–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- There are four types of COVID-19 vaccines: here’s how they work | Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/there-are-four-types-covid-19-vaccines-heres-how-they-work.

- Amani A, Njoh AA, Mouangue C, Cheuyem Lekeumo FZL, Mossus T. Vaccination Coverage and Safety in Cameroon; Descriptive Assessment of COVID-19 Infection in Vaccinated Individuals. Health Sci Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul 31 [cited 2022 Aug 31];23(8). Available from: http://www.hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/hsd/article/view/3806.

- Bonny, A.; Tibazarwa, K.; Mbouh, S.; Wa, J.; Fonga, R.; Saka, C.; Ngantcha, M.; Death, O.B.O.T.P.A.S.O.C. (.T.F.O.S.C. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death in Cameroon: the first population-based cohort survey in sub-Saharan Africa. Leuk. Res. 2017, 46, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong SYJ, Wi DH, Ro YS, Shin SD, Jeong J, Kim YJ, et al. Changes in the healthcare utilization after establishment of emergency centre in Yaoundé, Cameroon: A before and after cross-sectional survey analysis. PLOS ONE. 2019 Feb 8;14(2):e0211777.

- Reports | DHIS2 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 15]. Available from: https://dhis-minsante-cm.org/dhis-web-reports/index.html#/data-set-report.

- Nouetchognou, J.S.; Ateudjieu, J.; Jemea, B.; Mbanya, D. Accidental exposures to blood and body fluids among health care workers in a Referral Hospital of Cameroon. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshering, K.; Wangchuk, K.; Letho, Z. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of post exposure prophylaxis for HIV among nurses at Jigme Dorji Wanghuck National Referral Hospital, Bhutan. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0238069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandana BN, Likwela LJ. Connaissances, attitudes et pratiques des professionnels de santé face aux précautions standards en milieu hospitalier. Connaiss Attitudes Prat Prof Santé Face Aux Précautions Stand En Milieu Hosp. 2013.

- Djeriri, K.; Charof, R.; Laurichesse, H.; Fontana, L.; El Aouad, R.; Merle, J.; Catilina, P.; Beytout, J.; Chamoux, A. Comportement et conditions de travail exposant au sang : analyse des pratiques dans trois établissements de soins du Maroc. 2005, 35, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laraqui O, Laraqui S, Tripodi D, Zahraoui M, Caubet A, Christian V, et al. Évaluation des connaissances, attitudes et pratiques sur les accidents d’exposition au sang en milieu de soins au Maroc. Med Mal Infect - MED MAL INFEC. 2008 Dec 1;38:658–66.

- Gondo D, Effoh N, Adjoby R, Konan J, Koffi S, Diomande F, et al. Connaissances, attitudes et pratiques (CAP) du personnel soignant sur les accidents d’exposition au sang (AES) dans 4 maternités d’Abidjan. Rev Afr Anesth Med Urgences [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Jun 3];21(1). Available from: https://www.calameo.com/read/00456829377ef9fab7bf6.

- Al-Abhar N, Moghram GS, Al-Gunaid EA, Al Serouri A, Khader Y. Occupational Exposure to Needle Stick Injuries and Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage Among Clinical Laboratory Staff in Sana’a, Yemen: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Mar 31;6(1):e15812.

- Akpuh, N.; Ajayi, I.; Adebowale, A.; Suleiman, H.I.; Nguku, P.; Dalhat, M.; Adedire, E. Occupational exposure to HIV among healthcare workers in PMTCT sites in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbanya D, Ateudjieu J, Tagny CT, Moudourou S, Lobe MM, Kaptue L. Risk Factors for Transmission of HIV in a Hospital Environment of Yaoundé, Cameroon. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010 May;7(5):2085–100.

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Ritchie, H.E.; Mathieu, L.; Rodés-Guirao, C.; Appel, C.; Giattino, E.; Ortiz-Ospina, J.; Hasell, B.; Macdonald, D.; Roser, B.a.M. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Amani A, Mossus T, Cheuyem Lekeumo FZ, Bilounga C, Mikamb P, Atchou JB, et al. Gender and COVID-19 Vaccine disparities in Cameroon [Internet]. Public and Global Health; 2022 Jun [cited 2022 Jun 17]. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2022.06.12.22276293.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).