1. Introduction

1.1. Hygiene Programming in Crises

Humanitarian emergencies such as natural disasters, disease outbreaks or armed conflicts cause displacement of populations, the destruction of social systems and infrastructure and present increased public health risks. These conditions create the ideal environment for the spread of communicable diseases [

1,

2]. Of particular concern are diseases which transmit through a faecal-oral route. Faecal-oral pathogens include diarrhoeal diseases, some respiratory infections and many outbreak-related diseases (e.g. Cholera) and are a leading cause of preventable illness and death across all types of humanitarian crises [

2]. Handwashing with soap is known to be one of the most cost-effective public health interventions and can result in diarrhoeal disease reductions by up to 48% [

3,

4] and reductions of respiratory infections of by up to 23% [

5,

6,

7]. In stable settings (locations not affected by crises), handwashing promotion should be facilitated by exploring what determines whether people wash their hands. Handwashing interventions which have been developed based on an understanding of these determinants have been proven to change behaviour [

8,

9]. Handwashing promotion in humanitarian crises typically utilises hygiene education (e.g., communicating the health benefits of handwashing) and the provision of hygiene products (e.g., provision of soap and handwashing facilities). This narrow focus on handwashing knowledge or infrastructure has proved insufficient to change handwashing behaviour in these settings [

10]. This could be because these represent just two of the many possible determinants influencing handwashing practices of crisis-affected populations.

The limitations of hygiene programming in humanitarian crises have been recognised [

11,

12] but change within the humanitarian sector has been slow. Prior research [

12,

13,

14] has identified that this is likely to be because current behaviour change approaches have not been designed with humanitarian contexts in mind and are often explained in long, written documents that are hard to apply within humanitarian timelines. Secondly, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) practitioners see behaviour change as something outside their remit and the competency of development actors. Hygiene programmes are often under-funded and either replicate activities which practitioners have tried in other contexts or rely on external consultants to develop more tailored programming. Lastly, even though implementers are keen to improve their programmes based on evidence, they often struggle to find the time and capacity to contextualise and adapt ideas that have worked elsewhere [

12,

13,

14].

1.2. The Wash’Em Process

Wash’Em is a process designed to help implementers to assess and design rapid, evidence-based, and context-specific hygiene behaviour change programmes. The Wash’Em process is intended to make designing and implementing behaviour change programmes more feasible for implementers, irrespective of their prior training or experience, thereby mitigating the need for external ‘experts’ to be flown in to support programming. The first step to using the Wash’Em process is to learn about what the process involves (

Figure 1). Organisations can pick from a range of training formats based on their needs, including a facilitated online course and a face-to-face training for implementers [

15]. The second step in the Wash’Em process is for implementing staff to use a set of five Rapid Assessment Tools to learn about the determinants of handwashing behaviour from crisis-affected populations in their setting. The Rapid Assessments are participatory methods which focus on the determinants of handwashing behaviour that are most likely to be affected in a crisis and are designed to generate the kinds of data needed to influence program design. The five Rapid Assessment Tools are described in

Table 1 and can be viewed via Supplementary material document S1 to S5. The third step is to summarise the findings from the Rapid Assessments by entering them into the Wash’Em software [

16] and answering 48 multiple choice questions. This prompts the software to select from more than 80 recommended handwashing activities, those which are most likely to change behaviour based on the contextual determinants. Each activity comes with a step-by-step guide to aid organisations in planning the logistics and delivery of their programme. The Wash’Em process was designed based on several years of research and iterative improvements based on feedback from humanitarian actors [

14,

17,

18]. It can be completed in as little as two days [

19] and has already been used in more than 94 humanitarian responses since March 2020.

Although the Wash’Em process has been widely used by implementing actors, this uptake has happened largely independently, with humanitarians in crisis-affected settings discovering the tool and using it without consultation with the Wash’Em developers. This has meant that it has been challenging to understand the ‘on the ground’ successes and challenges that are being faced by implementing partners, how the process is being adapted to suit different contexts, and whether the Wash’Em designed activities are acceptable and relevant to populations. This process evaluation is designed to track each phase of implementing Wash’Em in a crisis-affected setting in Zimbabwe. The overall aim of the process evaluation is to better understand if Wash’Em improves the process for developing acceptable, feasible and context-appropriate hand hygiene programmes in crisis-affected settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Population Demographics

The study took place in two districts of the Midlands Province in Zimbabwe. Most of the population in this region earn their living through agricultural activities, with the main produce being cotton [

21]. Zimbabwe has experienced a prolonged water and food security crisis in recent years due to increasingly severe economic challenges, rapidly rising inflation and climate hazards [

22,

23]. This insecurity was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

21]. A baseline survey conducted by Action Contre La Faim/Action Against Hunger (ACF) and Africa Head (AA) in January 2022 covered the two study districts and found that 40% of respondents used surface water as their main source of drinking while 36% used boreholes. More than 50% of respondents reported to spend more than 30 minutes travelling to and from the water point and 72% of the respondents said they did not have access to adequate water. Only 15% of households had a dedicated place to wash hands with soap [

24].

ACF, in collaboration with local partner AA were funded to implement a programme entitled ‘Community System Strengthening for Reducing Vulnerability, Restoring Economic Sustainability, and Improving Recovery from COVID-19 in Zimbabwe’ in the study districts from July 2021 to January 2023. This multipronged humanitarian initiative included a component on WASH. ACF and AA planned to use Wash’Em to design the handwashing promotion component of the programme. In addition to hygiene, AA intended to repair and rehabilitate 48 boreholes which were dysfunctional and drill an additional 6 boreholes. ACF and AA planned to deliver their programme, including the handwashing component, in partnership with the local government and Village Health Workers (VHWs). Village Health Workers are unpaid volunteers that work under the Environmental Health Technicians (EHTs) to help promote public health initiatives at a community level in Zimbabwe. AHA and AA also intended the Wash’Em designed activities to be delivered to communities through their Community Health Club (CHC) model [

25,

26,

27,

28] which brings together community members on a weekly basis to learn about and tackle health challenges in their community. This approach, they envisioned, would help to ensure that the Wash’Em activities reached most of the population, were linked to other WASH initiatives and led to sustained action.

2.2. Study Design and Framework

A theory of change was developed to provide a framework for this study and outline how the Wash’Em process intended to influence programme design. This was informed by the UKRI Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidelines for Process Evaluations of complex interventions [

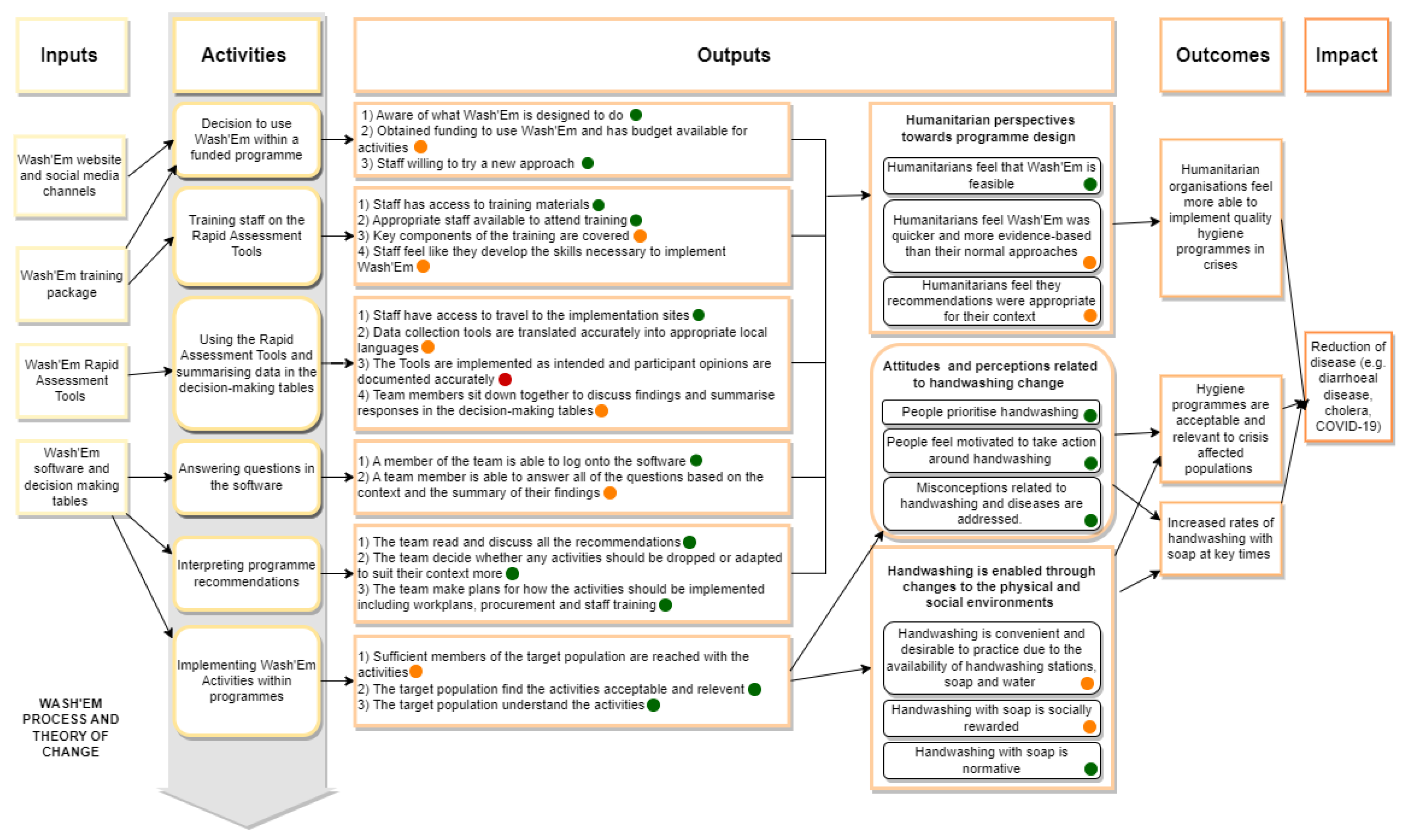

29] which is widely used for the evaluation of public health interventions. This is presented in

Figure 2 in the results section. This study was designed to assess four process domains which related to the steps that the organisations (AA, ACF, local government counterparts and the communities) followed to design the programme following the Wash’Em process. It also assessed nine programme domains relating to the actual programme that was implemented following the use of the Wash’Em process. All 11 domains were informed by the process evaluation guidance developed by Linnan and Steckler [

30], the MRC Guidelines and the stages of implementation as defined in in the Wash’Em programme design process. The domain definitions are available in

Table 2.

2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected from the start of the implementation of the Wash’Em designed hygiene programme (August 2022) and for the subsequent 6 months. A mix of qualitative methods were used including interviews with implementing staff, observations, photography and note taking throughout the design process and implementation; focus group discussions (FGDs) with the targeted crisis-affected populations; and secondary analysis of operational documents and programme reports.

Table 3 provides a summary of the methods used, their intention and the sample size used.

2.4. Interviews with Wash’Em Implementers

Interview participants were purposely sampled from all staff that were involved in the Wash’Em training or implementation of Wash’Em designed activities. Sampling was designed to include a mix of genders, experience, and positions within the implementation team. The in-depth interviews followed an interview guide (S6 Document) and aimed to investigate fidelity, context, acceptability, and feasibility of the Wash’Em process and programme. Interviews with these staff members took place after the Wash’Em implementation. In-depth interviews were conducted in person or remotely via Zoom, depending on the location and availability of staff. Interviews were done in either English or Shona language - whichever the staff member was more comfortable using. Interviews were led primarily by staff from Biomedical Research and Training Institute (BRTI) in Zimbabwe who were fully external to the implementation process. Staff from London School of Hygiene Tropical Medicine also supported interviews of AA and ACF staff remotely via zoom.

2.5. Observation, Notetaking, and Photography

Observation was used to assess whether the Wash’Em process was implemented as intended. The observation focused on key moments of the Wash’Em programme delivery including select moments during the delivery of Wash’Em designed activities. All observations were recorded on semi-structured observation forms which were specifically designed to track the intended steps at each implementation stage. Staff also took free-form notes and photos to complement this process. Observation was conducted by staff from BRTI.

2.6. FGDs with Crisis-Affected Populations

FGDs were held with crisis-affected populations living in villages where the Wash’Em designed handwashing programme was implemented. The study team recruited participants that could recall attending a meeting about handwashing in the last three months. All interviews were led by Shona speaking facilitators from BRTI. The focus group discussions followed an FGD guide (S7 Document) and aimed to investigate the acceptability and relevance of Wash’Em designed activities, participant engagement and response to the activities, and contextual factors affecting hygiene. FGDs took place at two time points, 2 and 8 months after the end of the implementation of Wash’Em designed activities. The second round of FGDs, conducted in May 2023, were done because after a preliminary analysis of the data the research team concluded that saturation had not been reached with the initial sample.

2.7. Secondary Analysis of Programme Documents

The implementing organisations provided several documents for secondary analysis. These included findings from the Rapid Assessments, outputs from the Wash’Em software, the broader programme baseline report, and the programme plans and budgets.

2.8. Data Management and Analysis

All interviews and FGDs were audio recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. The transcripts were then analysed thematically following the process outlined by Braun and Clarke [

31] and by using a coding structure based on the 11 process and programme domains described in

Table 2. All transcripts were double coded (by AHT and CVM) and disagreements discussed. Observational data, notes, photos, and programme documents were discussed by the evaluation team (LSHTM, BRTI and monitoring staff from ACF) and compared to the intended stages of Wash’Em use and the intended implementation of Wash’Em designed activities.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Study Participants.

In-depth interviews with implementers were conducted with 11 staff (one from ACF, four from AA, four EHTs and two VHWs). Three were female and eight were male. Those interviewed had between 1-13 years of experience working on either WASH programmes or on community health promotion. Nine focus groups were organised with 6-15 adult male and female participants in each. In total 56 people participated: 22 men and 34 women.

3.2. Category 1a: Implementation of the Wash’Em Process for Programme Design Compared to the Intended Process

Fidelity and Coverage

Figure 2 uses a traffic light system to indicate the extent to which the intended Wash’Em process was followed by in country implementers, with green indicating that the activity was completed as intended, orange indicating that the activity was partially carried out and red indicating that the activity was not carried out or carried out substantially different from what was intended. This visual summary and the written summary below are derived from observations of implementation and interviews with the implementation staff.

Figure 2.

Wash’Em Flow Diagram depicting the phases of implementation and the corresponding key actions that implementing organisations need to take. A traffic light system indicating the extent to which the intended process was followed by implementers has been applied.

Figure 2.

Wash’Em Flow Diagram depicting the phases of implementation and the corresponding key actions that implementing organisations need to take. A traffic light system indicating the extent to which the intended process was followed by implementers has been applied.

AA staff were introduced to the Wash’Em approach by ACF, and two AA staff were invited to attend a global online training on Wash’Em enabling them to develop a deep understanding of the approach and what it was designed to do. Wash’Em was written into a AA funding proposal, which expressly indicated that Wash’Em would be used to design the hygiene promotion component of their programme. However, the allocated funding covered the cost of the trainings, but no money was left for implementation of the Wash’Em designed programme. Staff within AA were excited to try a new approach to handwashing behaviour change because they recognised the limitations of some of their past programming. AA staff were introduced to the standard Wash’Em training materials [

16] during the global online training and then decided to modify and contextualise these materials to suit their purposes and allow them to deliver the training in a shorter space of time (1 day compared to the recommended 3 days). Ultimately, they delivered two in-person training sessions to a total of 22 staff across the two districts. Trainees included other staff from AA, Environmental Health Technicians (EHTs) from local Government and some volunteer Village Health Workers (VHWs). The condensed training timeline meant that some of the recommended training modules were covered rapidly or in some cases not covered at all. As such some implementation staff reported gaps in their understanding of Wash’Em.

The trained staff were able to travel to the programme sites the day after the training to use the Rapid Assessments. These were pre-translated by the AA staff but were not piloted with populations prior to use due to limited time and access to the programme locations. Data collection in both districts was complicated by the fact that the population was relatively dispersed, the districts were difficult to traverse, and the teams were only able to allocate 7 hours to data collection in each site. Due to these tight time constraints only three of the Rapid Assessment were utilised, with Disease Perception and Personal Histories being omitted in both districts because AA staff felt they were less relevant to their context (

Table 4, Quote 1).

Of the three Rapid Assessments that were implemented, the Touchpoint and Motives tools were implemented as intended within 6 focus groups. Twenty people participated in the Handwashing Demonstrations, but implementers reported prioritising houses nearby (therefore not applying guidelines for selecting a diverse sample) (S1 Document) due to time limitations and the dispersion of the population.

After collecting the data, staff in District 1 collectively entered the findings into the decision-making tables and Wash’Em programme designer software. Due to power outages in District 2 this collective process was not possible and instead was done by the lead trainer. In both districts the Handwashing Demonstrations Tool indicated that there were no handwashing facilities present at the household-level. Soap was available in half of the households but reported to be kept inside the main house, away from the kitchen and toilet. Water was also not stored in a location where it could be conveniently accessed for handwashing. In both districts, the Motives Tool revealed a need to increase the perceived link between handwashing and nurture (being a good parent) and disgust avoidance (being seen as a person who is neat). In District 1 handwashing was also linked to the motive of attractiveness (being seen as an attractive person) while in District 2 it was linked with status (being seen as a wise and well-educated person). The Touchpoint Tool indicated that the most effective ways of reaching the population in District 1 were through radio content, messaging at public transport hubs or through community meetings and events. In District 2 more people indicated that they had access to mobile phones and the tool also identified that schools and religious institutions could be appropriate ways of reaching the population.

Once the recommendations had been generated by the Wash’Em software, the training facilitators discussed the suggested activities with the training participants and decided which to implement. A total of 6 activities were recommended by the software for each district, with only one activity (‘The Power of Soap’) being recommended in both sites. A summary of the activities is presented in

Table 5 and a full description of each activity is available in SM3. In District 1 all activities were taken forward but in District 2 only one activity was taken forward and the rest of the programme utilised the activities recommended for District 1. This was because implementation staff felt that the finding from the Touchpoints Tool which indicated that most of the population had mobile phone access was not totally reliable as often people don’t have coverage, credit, or power to charge phones. Therefore, any activities that utilised phones or social media were dropped. AA also explained that they had a strong preference to continue to deliver hygiene programming through community events as that is what they are accustomed to. The ‘Watching Eyes’ activity was dropped because this was difficult to install with the type of handwashing facilities (Tippy Taps) that they were promoting. Once the activities had been decided on, many of the subsequent aspects of project planning (work plan development, procurement, and staff training) were done by engaging key staff as needed.

3.3. Category 1b: Implementation of the Wash’Em Designed Programme Compared to the Intended Process

3.3.1. Fidelity

The Wash’Em designed activities were intended to be implemented alongside a renewed curriculum for CHCs. However, due to delays in implementing the Wash’Em process, this was not possible and instead the previously designed activities were implemented by VHWs as they went house-to-house or worked with small groups doing hygiene promotion. As well as handwashing, the VHWs promoted menstrual hygiene management, the construction and safe use of household sanitation facilities, COVID-19 prevention behaviours, waste management, food hygiene and community water supply management.

Most Wash’Em implementation events were held outside community centres in the shade, under trees. All consumables required for the activities were purchased ahead of time by AA staff members. Due to the lack of funds available for implementation, staff had to draw from core budgets and other projects to cover the costs of the materials needed for implementation.

Table 3 presents an overview of the activities that were implemented. All activities were implemented with some local adaptations, reported in receipt and change mechanisms (

Table 4, Quote 2).

At each Wash’Em implementation event, 25 basic handwashing facilities and 25 bars of soap (a bucket with a tap attached often known as a veronica bucket) were distributed to the participants. Not all participants could receive a bucket as the budget only allowed for the purchase of 300 buckets. The distributions became divisive in some settings with participants feeling disappointed that they did not receive a handwashing facility when others did. In one community the VHW ensured there were only 25 people attending the implementation event. This approach led to a more peaceful and positive event but excluded members of the community from the programme. When asked about the organisation’s reasoning for purchasing and distributing a limited number of handwashing facilities, the implementers referenced the general tips section on the Wash’Em Programme Designer which states that when working with small hygiene budgets, organisations should focus resources on improving handwashing facilities and making soap more available for their population. The recommendations say this should be prioritised over the ‘soft’ part of the hygiene promotion given that handwashing infrastructure is so key for enabling practice. In addition to distributing handwashing facilities the implementers demonstrated how Tippy Taps [

32] can be constructed from locally sourced materials.

3.3.2. Coverage, Dose Delivered and Received

Initially, Wash’Em was intended to be implemented in every district and ward covered by the wider ACF and AA WASH response programme. However, due to delays in getting ethical approval for this study, AA and ACF agreed to implement the traditional handwashing promotion programme from the CHC in most wards in the two districts. A smaller group of 3 wards from each district that were not included in the CHC implementation were chosen to receive a customised Wash’Em designed intervention, as described above.

Implementation of the Wash’Em designed activities was conducted 2-3 months after the completion of the Wash’Em process to allow time for procurement and planning. In District 1, six implementation events were conducted. In District 2, six implementation events were planned and four completed (

Table 5). The number of participants at each event varied from 34-90. Most events had more women attending than men, due to men being busy at work during the day. In some instances, aging populations were unable to attend due to the challenge of transport to the event location. Observation notes indicated that the Wash’Em designed activities were delivered through stand-alone events on a range of weekdays. But in these districts, community meetings usually happen on Thursdays so leveraging these existing meetings could have led to higher attendance at implementation events (

Table 4, Quote 3).

According to the implementors, the VHWs in one ward in District 2 did not carry out the implementation of the hygiene programme due to the disgruntlement of the VHWs due to a lack of incentives.

3.4. Category 2a: Receipt and Mechanisms of Change (Implementers)

3.4.1. Feasibility (Process)

Overall, the senior implementers attending the training of trainers expressed that they found it useful and informative. The training left them prepared to organise and deliver their own face to face trainings. Reflecting on the structure of the implementer training, one staff member explained that although it was feasible to complete the training modules in one day, it was very intense and did not allow time for the participants to pause and reflect on the individual modules, due to the amount of content that had to be covered.

Due to power cuts at the venue for the training in District 2 the venue had to be evacuated due to the high temperatures inside without air conditioning. The training then had to be moved outside and completed in the shade of a large tree and using only printed materials as laptops used for presenting slides quickly ran out of power. The training facilitators were also concerned about the number of materials that had to be printed as it was a time and budget consuming task. However, they reflected that all the printed materials were useful and necessary for the effective completion of the training and allowed the participants to keep information about the training to refresh their memory at a later stage. The costs of the two implementer trainings and data collection was USD 2,552 USD, and included meals for training participants and venue costs.

When using the Rapid Assessment tools, implementers appreciated that the Wash’Em process allowed time for consulting with members of the community before designing and implementing hygiene promotion programmes (

Table 4, Quote 4).

Collecting data using the Rapid Assessment tools was considered a laborious process by implementers due to the long travelling distances from the training venue to the villages were crisis-affected populations were living. Furthermore, the distances between each household was far and only accessible by foot. Once the data collection team was present in the village, they used the AA implementers devices to capture quality videos for the Handwashing demonstrations tool.

The implementers reported that according to the Wash’Em training of trainers’ curriculum, the Personal Histories Tool should be used during a crisis or an outbreak. While their proposal defined the settings as being affected by a prolonged water and food security crisis, the AA implementers did not see this as being equivocal to the kind of disaster referred to in the tool, with staff viewing the current drought as ‘not that bad’. Furthermore, implementing staff explained that they understood that the Disease Perception Tool should only be used during or after a disease outbreak (such as COVID-19 or cholera), and that the chronic, high rates of diarrhoea in the districts did not merit being considered as an outbreak or a disease of concern.

3.4.1. Feasibility (Programme)

When ACF and AA’s wider WASH program was planned with a budget of USD 59,375, there was no funds allocated for the implementation of Wash’Em designed activities. This meant that the AA staff had to request additional funds to cover the cost of implementation. A total of USD 2,340 was spent on 300 handwashing facilities and 300 bars of soap. Other consumables needed for the implementation included food dye, bread, paper for printing and creating commitment cards, turmeric and Vaseline. However, no clear financial record exists for this spending and therefore was not able to be recorded accurately (

Table 4, quote 5).

The EHTs were paid their normal salary as they are employed by local government offices and the AA staff were on employment contracts and paid for their work. However, the implementers leading the implementation events and follow up, the VHWs, were not paid for their work and this was a significant barrier to their motivation for delivering Wash’Em activities. Some VHWs refused to implement activities due to lack of incentives, citing that other organisations would provide financial incentives for similar work. The VHWs, despite participating in the Wash’Em process, highlighted that they were overwhelmed as they are the focal entry point for all implementing agencies in the district. Given that AA did not provide financial incentives to the VHWs, they viewed the Wash’Em process and the associated activities as very intensive and time-consuming. Ultimately some VHWs reported prioritising the activities of the agencies that provided them with incentives, at the expense of Wash’Em.

3.5. Category 2b. Receipt and Change Mechanisms (Crisis-Affected Population)

3.5.1. Acceptability and Relevance

The recipients valued the fact that the hygiene promotion events in which the Wash’Em designed activities were implemented, were short in duration. Sessions took between one to two hours.

The activity ‘Being pulled in all directions’ (

Table 5) was implemented a total of 10 times in the two districts. AA officers made some adaptations when they translated the activity instructions, including adding local examples of chores a mother would usually have. The local adaptation allowed for a mother or a father to play the main role in the activity (

Figure 3).

Participants in the FGDs had the intended realisation this activity was designed to create, that is that after participating in this exercise they were able to see how women have a lot of chores that they need to do daily, and as such important behaviours like handwashing can sometimes be deprioritised (

Table 4, Quote 6). Observers noted that crisis-affected populations were eager to attend and were actively engaged in the activity but as the implementation events included both men and women, some women were felt uncomfortable engaging with men, given the physicality of this activity.

The ‘Dye on food’ activity (

Table 5) was amended by implementers to not include the first part where a table of food was set. Instead, the activity started by setting up activities where hands could be contaminated such as going to the toilet or changing a baby’s nappy, then immediately handling food or feeding the baby, therefore leading to contamination and facilitating the spread of germs. In the FGD, participants noted how the ‘Dye on food’ activity really helped to visually demonstrate how germs could move from one contaminated area and spread into their household which would explain the diarrhoea and cholera challenges that sometimes would be experienced in their area (

Table 4, Quote 7) (

Figure 4).

In the activity known as ‘Pledges’ (

Table 5), the implementers instructed participants to build on their experience of the ‘Power of soap’ activity which had demonstrated the importance of washing hands with soap and asked, “What things can you agree on that will help your community wash their hands with soap or ash regularly?”. Participants then agreed on several commitments to make together as a community: 1) building suitable toilets, 2) digging trash pits, 3) keeping food covered, 4) investing in handwashing stations around the homestead, 5) being more active in personal hygiene, and 6) investing in buying soap as a community. In some cases, the VHW facilitators sought and received the support of the headman and chief of the village. Implementers felt these hierarchies were a powerful influence to support this activity. VHW perceived that Wash’Em activities would continue beyond the presence or facilitation of AA because of the headman’s involvement and commitment to what was written on these pledges.

The ‘Child life game’ (

Table 5) was implemented four times in District 2. In one village this activity helped combat a local belief that children’s teething was a primary cause of diarrhoea. After the interactive play, the participants discussed with the facilitators and agreed that it was more commonly the child’s contaminated hands or other items they put in their mouth to sooth their sore gums that was the source of germs causing diarrhoea, not the teething itself. The activity ‘Child life game’ (

Table 5) was not implemented in District 1 as the implementers thought 5 handwashing activities were sufficient to promote handwashing in each village.

AA staff members prepared ‘Commitment cards’ (

Table 5) which were printed on paper at their offices before distributing these to VHWs to implement the activity at household level. The AA facilitators encouraged VHWs to work with each family to come up with a set of commitments, including building a toilet, water treatment and storage, digging a waste disposal, keeping their home environment clean as well as regularly washing hands with soap. Ultimately this meant that the activity was slightly less community led than intended.

3.5.2. Participant Engagement & Response

The crisis-affected population was observed to be engaged, interactive and overall pleased with the content of the hygiene promotion event (

Table 4, Quote 8). Participants expressed to the facilitators that they appreciated that the event did not last more than two hours, allowing them to get on with their day. Positive peer pressure through sharing knowledge as well as experiencing and understanding the handwashing promotion activities together elevated the community’s value placement on handwashing behaviours and associated WASH components.

3.5.3. Mediators

The Wash’Em designed activities appear to have had a positive influence on the number of households which built handwashing facilities. This is based on self-reports by crisis-affected populations who were exposed to the intervention who also described a marked change in their own behaviour and that of their neighbours (

Table 4, Quote 9). Secondly the EHTs collect data on handwashing indicators every quarter and reported that in the villages which the Wash’Em designed handwashing programme were implemented, there was more than a 90% increase in handwashing facilities at household level (

Figure 5). The handwashing facilities distributed by AA make up 57% of the new handwashing facilities reported. Within the scope of our research, we were not able to independently verify these self-reports or EHT data, however if accurate, this would indicate an increase from less than 1% of households having handwashing facilities to a coverage of more than 70% after the implementation of Wash’Em. Village 9 and Village 10 were the villages where the VHW did not implement any Wash’Em designed activities apart from distributing 25 veronica buckets in each village, and in these areas no additional handwashing facilities were reported 4 months after implementation. When comparing the villages that did not have Wash’Em designed activities implemented, the difference in number of new handwashing facilities built was marked, reported implementers.

3.6. Category 3: Context

The main external barrier to facilitating improved handwashing in these districts was identified by implementers and populations as being access to water (

Table 4, Quote 10). In addition to prolonged drought, the program was implemented during the dry season in August with rains expected between October 2022 and March 2023.

Although solidly constructed tippy taps can withstand general use by humans, another barrier to the effect of the programme was the destruction of the home-built handwashing stations by livestock and by children playing. Members of the community appreciated receiving soap from AA with the handwashing distribution but were worried about where the next bar of soap would come from as the costs of the soap was a barrier for purchase. Implementers noted that if the rainy season started as scheduled, they expected an increase in use of the newly distributed buckets and tippy taps for the collection of rainwater but felt that the additional access to water would ultimately make handwashing easier and more convenient for the community.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that in this context, the Wash’Em process was not fully implemented as intended. Of the 19 first-level outputs (as described in

Figure 2) 11 were coded green indicating that they had basically been implemented as intended. The remainder were only partially implemented (seven outputs), not implemented or differed substantially from what was intended (one output). Specifically our findings indicate that in Zimbabwe an abridged training was utilised; two of the five Rapid Assessment Tools were considered less relevant and omitted; many of the recommended activities were not implemented (particularly in District 2), the delivery modalities were different to what was proposed by ACF and AA but were also different to what was recommended by the Wash’Em software; the budget available was utilised on the initial CHC implementation and the training leaving minimal financial resources for the actual implementation; and the number of people exposed to activities was fewer than hoped.

Of the second-level outputs defined in

Figure 2, five of the nine were achieved in Zimbabwe. Implementers in general felt the Wash’Em approach was feasible, and populations exposed to the intervention reported that the Wash’Em designed activities led them to prioritise handwashing, took action around handwashing (e.g., building handwashing facilities), made the behaviour seem normative, and addressed misconceptions around handwashing and diseases that they held.

However other secondary-level outputs along the theory of change were only partially met. For example, implementing staff from ACF and AA did not feel that all of the Wash’Em recommended activities were relevant to their setting. Primarily this was because in District 2 the Touchpoints tool indicated digital media and radio may be effective ways reach populations, but based on the implementation team’s experiences this was likely to be impractical. The team opted to go for a more familiar delivery modality (in-person interactions) and an approach that was more aligned across the two districts. This decision meant that some of the nuance of the contextualisation that Wash’Em can offer was lost, and some of the other secondary-level outputs were not realised. For example, the Wash’Em activities also struggled to make handwashing more convenient and socially rewarded, because the activities that related to these outputs were dropped. The Wash’Em process does allow for ‘replacement activities’ to be selected if implementers feel some of the activities are less relevant but this feature was not utilised in Zimbabwe. It is not unexpected that implementers will customise and change the recommended activities to suit their own needs. In this case the decision made the programme easier to roll out across the two districts and allowed some innovative approaches to be utilised within a familiar delivery modality. Supporting innovation uptake within the humanitarian sector has been documented to take time. One reason for this because the chaotic nature of operating in a crisis tends to make actors risk averse, less prone to adopting innovative ideas and more likely to rely on what is familiar [

33,

34,

35]. Overcoming this requires a broad understanding of humanitarian decision-making processes and consultations with Wash’Em users to understand how support can be provided at this programme planning stage.

Some of the implementation team felt that the standard Wash’Em use timelines (approximately a week) was still too time consuming for their needs and for the constraints of accessing communities in their setting. The process may have seemed time consuming because most programmes previously designed in this context were developed by senior staff and with less active participation from the community. This type of ‘top-down’ programme design is not unusual for crisis response programmes. Prior research on hygiene programme design in these settings [

12,

13,

14] has indicated that implementers often have to compromise on more ‘ideal’ processes of programme design due to the perceived imperative to act with urgency and the associated time pressures and stress that come with this. As such programmes tend to rely on the past expertise of managerial staff to make decisions since it is not always possible for organisations to set aside time to learn from communities [

14,

33,

36]. Even when engagement with communities does take place, many programme teams struggle to use this data to contextualise programmes [

14]. However, when community engagement is done well and when learning feeds back into programme implementation, research indicates that programmes are more accepted, relevant, trusted and likely to lead to positive outcomes [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Indeed, in our study, implementers recognised that even though Wash’Em took more time, it was the in-person qualitative data collection that the implementing team valued and which they felt led to more contextualised and holistic programmes. There has been a strong push in recent years for anthropology and qualitative science to be better utilised to support humanitarian and outbreak programming [

41,

42,

43]. However, achieving this has been inherently challenging because the ‘humanitarian worldview’ is often epistemologically and methodologically at odds with the anthropological approach. This has led to qualitative science sometimes being seen by humanitarians as unscientific, unpragmatic, time-consuming, and something that requires specialist expertise [

41,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Wash’Em provides a semi-structured way for humanitarians, with limited experience in qualitative methods, to engage with communities and immediately use the results to influence programme design. As the name suggests, the Rapid Assessment Tools are not intended to be as ‘deep’ as traditional anthropological methods but may serve as a useful way of starting to strengthen qualitative capacities in the sector, something that has been acknowledged as weakness in past responses [

14,

47,

48].

The process of implementing Wash’Em may have also seemed burdensome to implementers in Zimbabwe because budgets were so limited. It is not unusual for humanitarian organisations to be working with limited budgets for hygiene programming and this has been recognised as a chronic challenge in the sector [

14,

19,

49,

50]. The Zimbabwean team decided to prioritise the limited funds they had for handwashing infrastructure. This was consistent with Wash’Em guidelines which recommend this because creating convenient and desirable handwashing facilities is likely to be the most influential determinant of handwashing behaviour [

18,

51]. However, with limited funds they were not able to purchase enough facilities for the whole target population. This created challenges for implementing staff and was divisive among communities. It is important that programmes can facilitate infrastructural changes in an equitable and sustainable manner. Global guidance on equitable commodity distributions exists [

52], however achieving this is likely to require a two-pronged approach consisting of increased and sustained financing from humanitarian donors and more effective engagement with communities to allocate resources and leverage local knowledge and innovations.

Wash’Em was implemented within a broader programme designed by ACF and AA which was intended to be multi-sectoral and address a range of needs facing the affected communities, including improving water access. This is consistent with Wash’Em guidance which emphasises that handwashing programming should not be seen as a stand-alone initiative. However, in practice the programme was not able to meet the scale of needs in the target areas. For example, there were an increased number of functioning water points in the region as a result of the programme, but most people exposed to the Wash’Em component of the programme did not experience meaningful improvements in water access. Therefore, populations in our study indicated that, despite generally liking the Wash’Em activities, their lack of water access was still a major barrier to regular handwashing practice. This finding acts as a reminder of the importance of designing humanitarian programmes that are holistic, cross-sectoral and sustainable. However, with current humanitarian funding only meeting 50% of global needs, the challenge of achieving meaningful change at scale is immense. Greater collaboration with government partners and the private sector is likely to be required to close the gap [

53].

A further challenge facing Wash’Em’s implementation in Zimbabwe was that the VHWs who were primarily responsible for delivering Wash’Em activities in communities were not renumerated for the additional time the Wash’Em activities took. While the payment of per diems or other forms of financial incentives can have complex flow on consequences [

54,

55], humanitarian programmes must be cautious that their programme design choices and delivery modalities do not create additional burdens on frontline staff, such as VHWs, who are often undervalued, time and resource limited and have to deal with a multitude of responsibilities while working under challenging conditions [

56,

57]. Reflecting on these power dynamics and the relationships between the different levels of implementing staff, should be an important aspect of undertaking quality programming [

58] and future implementation science research.

4.1. Implication of the Findings for Improving the Wash’Em Process

The Wash’Em process has been improved based on some of these observed deviations from the intended process. For example, it is now a requirement that users complete at least four Rapid Assessments in order to generate sufficient data for contextualisation of activities. A stark finding of this evaluation was that the protracted nature of the water and food security crisis in Zimbabwe was not viewed as a ‘crisis’ by frontline staff, nor did they view chronic diarrhoea challenges in the region as being a significant or unique disease risk. These variations in understanding have caused the global-level Wash’Em trainers to rethink the way fragility, crises and outbreaks are described and has prompted the team to reflect on how Wash’Em can be used to support resilience building and crisis mitigation programming. Issues related to budgeting for Wash’Em, were already a concern for the Wash’Em team and subsequently guidance is now available on how to effectively write Wash’Em into a proposal and develop and adequate budget [

59]. Finally, the results of this process evaluation highlighted that the stage where users assess the recommended activities, select which to implement and develop programme plans, is key. The Wash’Em developers have subsequently placed stronger emphasis on this stage of the process and have developed a programme planning tool to guide implementing actors through questions related to delivery modality, sustainability, cross-sectoral programming, logistics and procurement.

4.2. Limitations

Our ability to undertake a robust process evaluation was affected by a 9-month delay in gaining formal ethical approval for the study in Zimbabwe. This meant that the implementation of the Wash’Em process started before the process evaluation could commence and as such, we had to reply on secondary programmatic data describing the Wash’Em training, Rapid Assessment tool use, data entry and programme planning. This was then complemented with retrospective reflections on these stages of the process via the interviews with implementers. This inability to collect primary data during these stages of Wash’Em use (as initially proposed) resulted in some gaps in our understanding of how the Wash’Em design process was followed. Compressed timelines also resulted in us having to drop a household before and after survey which was intended to collect data on exposure to the intervention, mediating factors and behavioural outcomes (assessed through a proxy measure of whether handwashing facilities with soap and water were available. Unfortunately, this means that our understanding of intervention mediators and behavioural impact is self-reported and likely to be subject to social desirability bias. These are common challenges with evaluating handwashing behaviour change interventions [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. The delays we experienced reflect a broader challenge of undertaking implementation science in fragile settings which is that evaluations are often funded as stand-alone research activities which must align with separately funded ongoing programmes. Under this type of common funding modality, it is challenging not only align timelines but also to find common motivation across and donor, programme implementer and researcher interests. Similar challenges have been reported by others undertaking programme evaluations in complex crises or outbreaks [

65,

66,

67]. Mitigating such challenges could be possible if donors prioritise process evaluations within programme funding and encourage greater collaboration on such grants between academic partners and implementing actors.

5. Conclusions

Despite the real-world challenges of implementing Wash’Em amid the constraints of tight project timelines, limited funding, difficult terrain, and minimal changes to water infrastructure, the overall benefits of using Wash’Em to inform programme design appear to have been appreciated by implementers and populations alike. The prospect of utilising a novel process, like Wash’Em, to aid program design may initially seem daunting to implementers, but our findings indicate that programmes informed by community consultation and underpinned by theory and evidence are likely to yield positive results even if processes are followed imperfectly.

Supplementary Materials

S1. Document_Rapid Assessment tool guide: Handwashing Demonstrations, S2. Document_Rapid Assessment tool guide: Motives, S3. Document_Rapid Assessment tool guide: Disease Perception, S4. Document_Rapid Assessment tool guide: Personal Histories, S5. Document_Rapid Assessment tool guide: Touchpoints, S6. Document_In-depth Interview guide for implementing staff, S8. Document_Results of the Wash'Em Process - Activities recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AHT, SW and TH; methodology, AHT and SW; formal analysis, AHT and CVM; investigation, CVM, MT, JL, APM and TH; data curation, AHT; writing—original draft preparation, AHT and SW; writing—review and editing, JL, MT, CVM, APM, TH; project administration, TH, EZ, JL, CVM and MT.; funding acquisition, SW and TH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (grant number: AID-ODA-G-16-00270). The funding body played no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript. The contents are the responsibility of the authors of the paper and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s Ethics Review Board (26396) and the Biomedical Research and Training Institutional Review Board (AP173/2022), and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/2853).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of interview subjects.

Acknowledgments

The study team would like to extend our gratitude to Livision Chipatiso, Annah Matsika (ACF) for their contribution to the delivery of this study. We would like to thank the implementing staff and crisis affected population who participated in this research and who were willing to give up their time for this study and reflect openly on their experiences. This research was undertaken as part of the Wash’Em Project which aims to improve handwashing promotion in humanitarian crises. This research was supported by the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (grant number: AID-ODA-G-16-00270). The funding body played no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript. The contents are the responsibility of the authors of the paper and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Conflicts of Interest

TH and SW were involved in the design of the Rapid Assessment Tools and Wash’Em Software. APN, EZ and TH work within Action Contre la Faim which was one of the subjects of this process evaluation. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Francesco Checchi, M.G. , rebecca Freeman Grais, Edward J. Mills, Public Health in crisis affected populations. A practical guide for decision-makers., H.P. Network, Editor. 2007, Overseas Development Institute: London, UK.

- Connolly, M.A. , et al., Communicable diseases in complex emergencies: impact and challenges. The Lancet, 2004. 364(9449): p. 1974-1983. [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, S. , et al., Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea. Int J Epidemiol, 2010. 39 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): p. i193-205. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C. , et al., Hygiene and health: systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop Med Int Health, 2014. 19(8): p. 906-16. [CrossRef]

- Rabie, T. and V. Curtis, Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: a quantitative systematic review. Trop Med Int Health, 2006. 11(3): p. 258-67. [CrossRef]

- Ross, I. , et al., Effectiveness of handwashing with soap for preventing acute respiratory infections in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 2023. 401(10389): p. 1681-1690. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.E. , et al., Effect of Hand Hygiene on Infectious Disease Risk in the Community Setting: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 2008. 98(8): p. 1372-1381. [CrossRef]

- Biran, A. , et al., Effect of a behaviour-change intervention on handwashing with soap in India (SuperAmma): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health, 2014. 2(3): p. e145-54. [CrossRef]

- Dreibelbis, R. , et al., Behavior Change without Behavior Change Communication: Nudging Handwashing among Primary School Students in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2016. 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.M. , et al., Soap is not enough: handwashing practices and knowledge in refugee camps, Maban County, South Sudan. Confl Health, 2015. 9: p. 39. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A. , et al., Evidence on the Effectiveness of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Interventions on Health Outcomes in Humanitarian Crises: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE, 2015. 10(9): p. e0124688. [CrossRef]

- Vujcic, J., P. K. Ram, and L.S. Blum, Handwashing promotion in humanitarian emergencies: strategies and challenges according to experts. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2015. 5(4): p. 574-585. [CrossRef]

- Czerniewska, A. and S. White, Hygiene programming during outbreaks: a qualitative case study of the humanitarian response during the Ebola outbreak in Liberia. BMC Public Health, 2020. 20(1): p. 154. [CrossRef]

- White, S. , et al., How are hygiene programmes designed in crises? Qualitative interviews with humanitarians in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Iraq. Conflict and Health, 2022. 16(1): p. 45. [CrossRef]

- 15. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, C.f.A.W.a.S.T., Action Contre la Faim. Wash'Em Training 2023 8 June 2023]; Available from: https://www.washem.info/en/training.

- 16. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, C.f.A.W.a.S.T., Action Contre la Faim. Wash'Em. 2023 31 March 2023]; Available from: www.washem.info.

- Thorseth, A.H. , et al., An exploratory pilot study of the effect of modified hygiene kits on handwashing with soap among internally displaced persons in Ethiopia. Conflict and Health, 2021. 15(1): p. 35. [CrossRef]

- White, S. , et al., The determinants of handwashing behaviour in domestic settings: An integrative systematic review. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2020. 227: p. 113512. [CrossRef]

- Jenny Lamb, A.H.T. , Amy MacDougall, William Thorsen, Sian White, he determinants of handwashing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country analysis of data from the Wash’Em process for hygiene programme design. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square 2023.

- 20. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, C.f.A.W.a.S.T., Action Contre la Faim. Wash'Em Rapid Assessments. 2023 8 June 2023]; Available from: https://www.washem.info/en/rapid-assessments.

- Council, F.a.N. , Gowke South District Response Strategy in the Context of COVID-19, S.a.I.R.a.D.C. Food & Nutrition Council, Editor. 2021.

- Muzenda, C.S.V. , Ave, S.M., ZIMBABWE NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 1 “Towards a Prosperous & Empowered Upper Middle Income Society by 2030” January 2021 – December 2025.

- . 2020, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development: Mgandane Dlodlo Building.

- OCHA, Zimbabwe: Humanitarian Response Dashboard (January-June 2021), U.O.f.t.C.o.H. Affairs, Editor. 2021: Zimbabwe.

- Zimbabwe, A.A.H. , Community System Strengthening for Reducing Vulnerability, Restoring Economic Sustainability, and Improving Recovery from COVID-19 in Zimbabwe - Baseline Survey Report. 2022.

- Africa Ahead, A.C.L.F. , Community Health Clubs: How do they Work? 2013.

- Waterkeyn, J., Decreasing communicable diseases through improved hygiene in.

- community health clubs, in MAXIMIZING THE BENEFITS FROM WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION, s.W.I. Conference, Editor. 2005: Kampala, Uganda.

- Waterkeyn, J.A. and A.J. Waterkeyn, Creating a culture of health: hygiene behaviour change in community health clubs through knowledge and positive peer pressure. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2013. 3(2): p. 144-155. [CrossRef]

- Juliet Anne Virginia, W. , et al., Comparative Assessment of Hygiene Behaviour Change and Cost-Effectiveness of Community Health Clubs in Rwanda and Zimbabwe, in Healthcare Access, B. Umar, R. Urška, and T. Sonja Šostar, Editors. 2019, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 3.

- Moore, G.F. , et al., Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 2015. 350: p. h1258. [CrossRef]

- Steckler, A.E. and L.E. Linnan, Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. 2002: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Braun, V. and V. Clarke, Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 2006. 3(2): p. 77-101.

- TippyTap.org. TippyTap - Save water, save lives. 2023; Available from: https://www.tippytap.org/.

- Martin, A. and G. Balestra, Using Regulatory Sandboxes to Support Responsible Innovation in the Humanitarian Sector. Global Policy, 2019. 10(4): p. 733-736. [CrossRef]

- Obrecht, A. and A.T. Warner, More than just luck: innovation in humanitarian action. 2016: Humanitarian Innovation Fund.

- Betts, A.B. , Louise, Humanitarian Innovation: State of the Art in OCHA Policy and Studies Series OCHA, Editor. 2014.

- Knox Clarke, P. and L. Campbell, Decision-making at the sharp end: a survey of literature related to decision-making in humanitarian contexts. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 2020. 5(1): p. 2. [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, S., Bedson, J., Community Engagement in Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response: Lessons from Recent Outbreaks, Key Concepts, and Quality Standards for Practice, in Communication and Community Engagement in Disease Outbreaks, ed. Springer. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, B. , et al., Community engagement for COVID-19 prevention and control: a rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 2020. 5(10): p. e003188. [CrossRef]

- Vanderslott, S. , et al., How can community engagement in health research be strengthened for infectious disease outbreaks in Sub-Saharan Africa? A scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health, 2021. 21(1): p. 633. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A. , et al., Engaging 'communities': anthropological insights from the West African Ebola epidemic. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2017. 372(1721). [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, H.C. , et al., The Importance of Developing Rigorous Social Science Methods for Community Engagement and Behavior Change During Outbreak Response. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 2021. 15(6): p. 685-690. [CrossRef]

- Enria, L. , Citizen Ethnography in Outbreak Response: Guidance for Establishing Networks of Researchers, S.S.i.H.A. (SSHAP), Editor. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bardosh, K.L. , et al., Integrating the social sciences in epidemic preparedness and response: A strategic framework to strengthen capacities and improve Global Health security. Globalization and Health, 2020. 16(1): p. 120. [CrossRef]

- Darryl, S. , et al., Anthropology in public health emergencies: <em>what is anthropology good for?</em>. BMJ Global Health, 2018. 3(2): p. e000534.

- Johnson, G.A. and C. Vindrola-Padros, Rapid qualitative research methods during complex health emergencies: A systematic review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 2017. 189: p. 63-75. [CrossRef]

- Lees, S. , et al., Contested legitimacy for anthropologists involved in medical humanitarian action: experiences from the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic. Anthropology & Medicine, 2020. 27(2): p. 125-143. [CrossRef]

- Susante, H.v. , Perceptions and Experiences of Qualitative Data Use in Humanitarian Contexts: A Case Study of Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), K.R.T. Insititute, Editor. 2022: Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Gillian, M. , et al., ‘The response is like a big ship’: community feedback as a case study of evidence uptake and use in the 2018–2020 Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMJ Global Health, 2022. 7(2): p. e005971.

- UN-GLAAS, Hygiene: UN-Water GLAAS findings on national policies, plans, targets and finance. 2020: Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO, State of the world's hand hygiene: A global call to action to make hand hygiene a priority in policy and practice, U.N.C.s.F.a.W.H. Organization, Editor. 2021, World Health Organization.

- Wolf, J. , et al., Handwashing with soap after potential faecal contact: global, regional and country estimates. International Journal of Epidemiology, 2018. 48(4): p. 1204-1218. [CrossRef]

- (EPRS), E.P.a.R.S. , Emergency Handbook: Commodity distribution (NFIs, food), ed. T.U.R. Agency. 2018: UN High Commisioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

- Oxfam, Still too Important to fail: Addressing the humanitarian financing gap in an era of escalating climate impacts 2023.

- Samb, O.M., C. Essombe, and V. Ridde, Meeting the challenges posed by per diem in development projects in southern countries: a scoping review. Global Health, 2020. 16(1): p. 48. [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, Y. , et al., Reflections on per diems in international development projects: Barriers to and enablers of the project cycle. Development Southern Africa, 2018. 35(6): p. 717-730. [CrossRef]

- Ndu, M. , et al., The experiences and challenges of community health volunteers as agents for behaviour change programming in Africa: a scoping review. Glob Health Action, 2022. 15(1): p. 2138117. [CrossRef]

- Kasteng, F. , et al., Valuing the work of unpaid community health workers and exploring the incentives to volunteering in rural Africa. Health Policy and Planning, 2015. 31(2): p. 205-216. [CrossRef]

- Finley, E. , Closser S, Sarker M, Hamilton AB, Editorial: The theory and pragmatics of power and relationships in implementation. Front. Hwlth Serv., 2023. 3:1168559. [CrossRef]

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, C.f.A.W.a.S.T. , Action Contre la Faim. Wash'Em: How to write Wash'Em into a proposal. 2023 31 March 2023]; Available from: https://washem-guides.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/washem_quicktip_proposal.pdf.

- Contzen, N., S. De Pasquale, and H.-J. Mosler, Over-Reporting in Handwashing Self-Reports: Potential Explanatory Factors and Alternative Measurements. PLOS ONE, 2015. 10(8): p. e0136445. [CrossRef]

- Dickie, R. , et al., The effects of perceived social norms on handwashing behaviour in students. Psychol Health Med, 2018. 23(2): p. 154-159. [CrossRef]

- Grover, E. , et al., Social Influence on Handwashing with Soap: Results from a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2018. 99(4): p. 934-936. [CrossRef]

- Mortel, v.d. and F.G. Thea, Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2008. 25: p. 40-48.

- Shane, T. , et al., It depends on how you ask: measuring bias in population surveys of compliance with COVID-19 public health guidance. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2021. 75(4): p. 387.

- D’Mello-Guyett, L. , et al., Distribution of hygiene kits during a cholera outbreak in Kasaï-Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo: a process evaluation. Conflict and Health, 2020. 14(1): p. 51.

- Warsame, A. , et al., The practice of evaluating epidemic response in humanitarian and low-income settings: a systematic review. BMC Medicine, 2020. 18(1): p. 315. [CrossRef]

- Majorin, F. , Jain, A., El Haddad, C., Zinyandu, E., Gharzeddine, G., Chitando, M., Maalouf, A., Sithole, N., Doumit, R., Azzalini, R., Heath, T., Seeley, J., White, S., Using the Community Perception Tracker to inform COVID-19 response in Lebanon and Zimbabwe: A qualitative methods evaluation. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).