1. Introduction

Central Asia has long been a volatile region riddled with geopolitical tensions and relentless conflicts over water resources. Among the post-Soviet republics in Central Asia, Uzbekistan, as a landlocked country, finds itself grappling with formidable challenges in effectively managing its water resources (Holmatov et al., 2016). Given its arid climate and surging water demand, it is imperative for Uzbekistan to urgently embrace sustainable water practices. However, the region's heavy reliance on the Amudarya and Syrdarya rivers as primary water sources, coupled with neighboring republics' unabashed consumption of copious amounts of water through extensive irrigation, presents a critical issue. The deteriorating state of irrigation infrastructure, predominantly remnants of the Soviet era (Brauch, 2009), has further exacerbated the loss of water and inefficiency in its utilization. The heart of the matter lies in the shared rivers, where conflicts and disputes emerge among neighboring countries regarding the use and distribution of this precious resource. In recent years, Uzbekistan's new government, assuming power after 2017, has initiated half-hearted and feeble efforts to address water-related challenges and repair crumbling irrigation infrastructure. These inadequate attempts manifest as hollow regional water diplomacy and cooperation purportedly aimed at resolving disputes over water resources. However, it is evident that these actions fall significantly short of addressing the urgent need for effective water management and distribution in the region. Unfortunately, tensions over water resources persist unabated, molding the geopolitical landscape with each passing day.

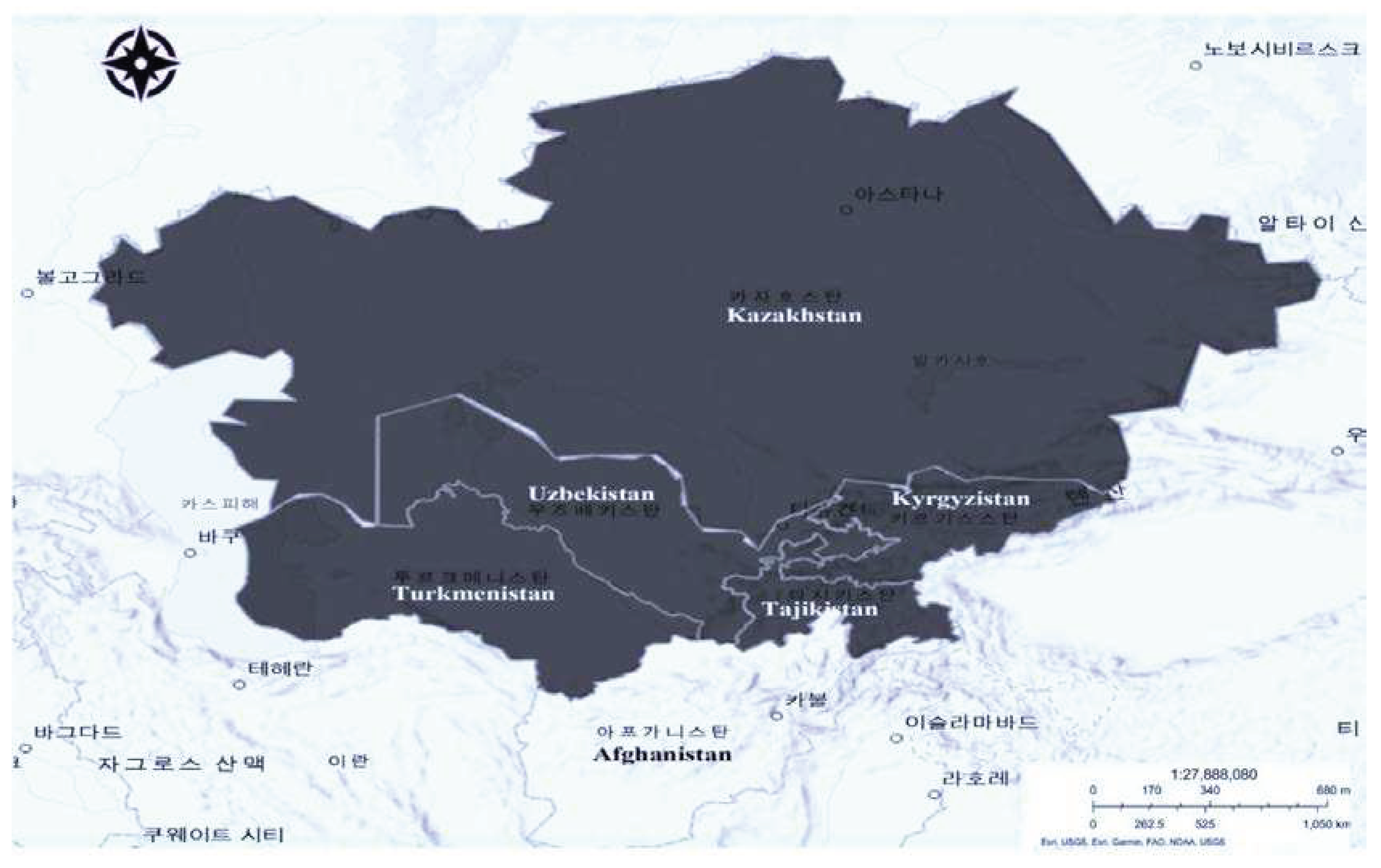

This study aims to undertake a comprehensive examination of the geopolitical dimensions underlying the water issue between Uzbekistan and its neighboring republics, with a specific focus on the Amudarya and Syrdarya river basins. The primary objective is to dissect and analyze the causes and factors contributing to conflicts and disagreements surrounding water issues. By doing so, we intend to shed light on the far-reaching implications these conflicts have on peace, security, and human welfare in Central Asia. Moreover, we strive to explore holistic solutions to avert the impending water crisis looming large over the region. This study adopts a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating incisive geopolitical analysis, rigorous geographic examinations, and valuable insights from relevant studies and works. We will employ qualitative research methods, including meticulous literature reviews, comprehensive data analysis, and insightful case studies, to foster a holistic understanding of the intricate web of water-related challenges plaguing Central Asia (

Figure 1).

In our quest for a comprehensive understanding of the water issue, we turn to the concept of resource nationalism or hegemony, which provides a suitable framework for analyzing the dynamics of water resources within the region. Through this lens, we seek to unravel how the control and distribution of water resources shape precarious geopolitical relationships and fuel unrelenting conflicts. Inextricably linked to this study is the seminal “soft power theory” pioneered by Joseph Nye in the 1990s. “Soft power”, characterized by a nation’s ability to exert influence through cultural, economic, and diplomatic means, holds immense relevance in the context of the water issue (Zaharna, 2021). The genuine pursuit of soft power diplomacy can play a pivotal role in fostering cooperation, resolving conflicts, and spearheading sustainable water management initiatives throughout Central Asia. This study builds upon previous work that has boldly examined the geopolitical dimensions of water resources in different regions. These studies highlight the critical role of resource interdependence and emphasize the need for regional cooperation to address water scarcity. Notable contributions include David Reed’s “Water, Security, and U.S. Foreign Policy” (2017), which underscored the link between water scarcity, national security, and the importance of comprehensive water management strategies. Aaron Wolf’s “Hydropolitics along the Jordan River” (1995) examined the geopolitical dimensions of water scarcity and aligns with our examination of tensions over shared water resources in Uzbekistan and neighboring republics. François Molle and colleagues’ “Hydraulic bureaucracies and the hydraulic mission [...]” (2009) offered insights into managing water resources in unstable regions and inspire our pursuit of holistic solutions in Central Asia. Anton Earle et al. “Transboundary water management and the climate change debate” (2015) examined the challenges of transboundary water management and guide our analysis of increased cooperation in Central Asia. Salman and Uprety’s “Conflict and Cooperation on South Asia's international rivers: A legal perspective” (2021) extended our understanding of water conflicts and legal frameworks beyond Central Asia. Building on this work, our study aims to comprehensively analyze water issues in Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries, examine the causes of conflict, and present holistic solutions with implications for peace. Through collaborative efforts, we can overcome the grip of water scarcity and forge a better future.

2. Background of the Study

Recently Uzbekistan experienced a severe power outage caused by a systemic failure in the Sirdarya thermal power plant, leading to a cascade effect that affected Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan as well (January 2022). This synchronized disruption of the power grid had significant implications, especially considering the harsh winter conditions during the blackout. The incident highlighted the reliance on outdated Soviet-era power infrastructure and emphasized the interdependency among these nations for their energy supply (source:

www.gazeta.uz, 2022/03/16). Similarly, in May 2020, Uzbekistan faced another calamitous event with the collapse of the “Sirdaryo” thermal power plant’s “Sardoba” dam in the Syrdarya region, a crucial nexus in Central Asia's energy grid (Xiao et al., 2022). The breach resulted in widespread flooding across extensive agricultural areas, impacting not only Uzbekistan but also neighboring Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. This dam failure brought attention to the pressing issue of transboundary water management in the water-scarce region. Tajikistan, known for its hydropower potential in Central Asia, also faces challenges in providing electricity to its citizens as water levels in the hydropower-generating rivers continue to decline. This predicament poses threats to the quality of life for the populace and the agricultural sector within the country (source:

www.eurasianet.org, 2023/04/04).

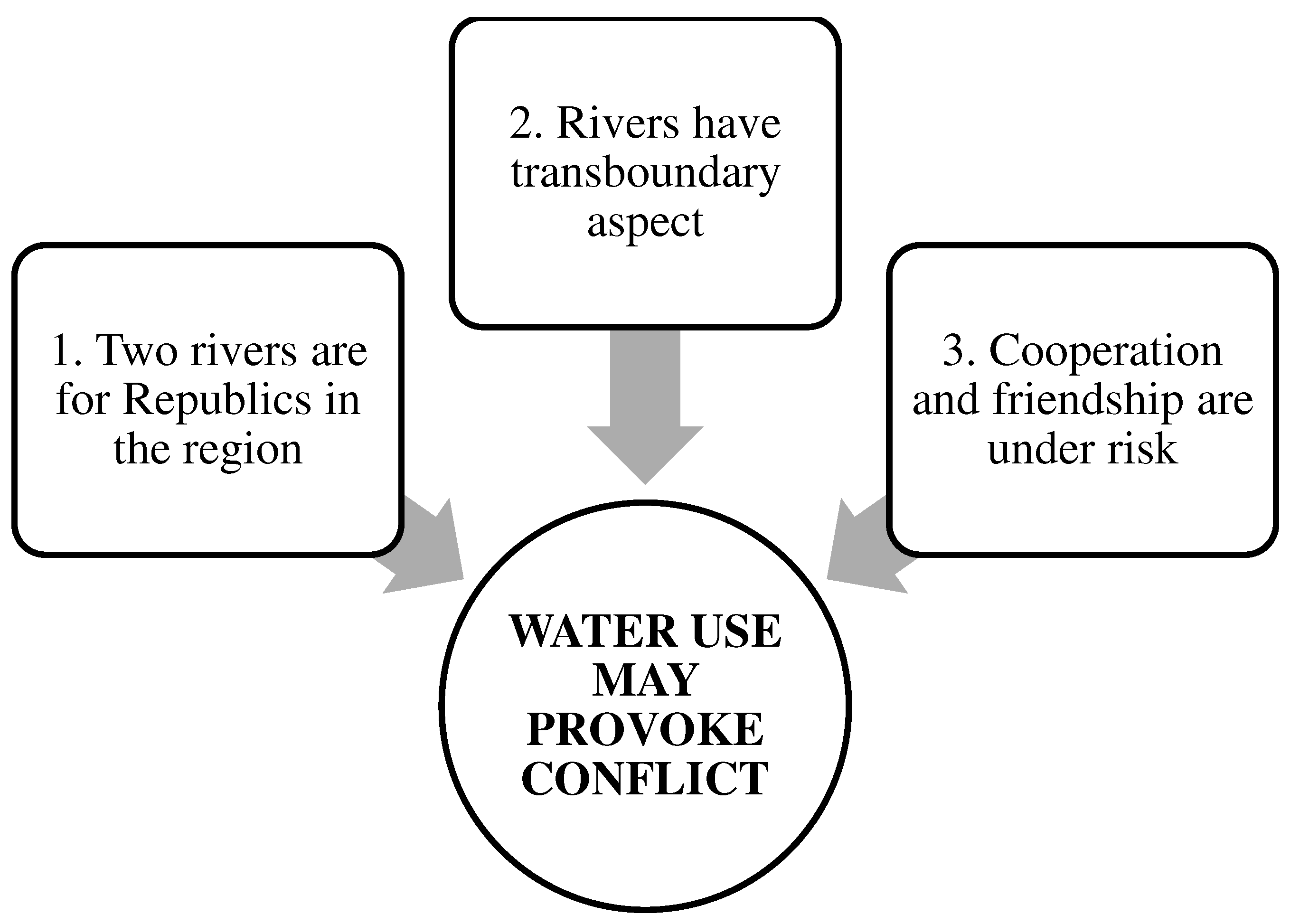

Kyrgyzstan, a mountainous nation rich in water resources, grapples with water scarcity despite its water abundance. This water crisis carries significant implications for the socio-economic development of the country, as Kyrgyzstan primarily exports hydroelectric energy to neighboring countries, particularly Uzbekistan. The presence of the Fergana Valley, which extends into Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, creates conflicts in the border areas. Additionally, two districts of the Fergana region are located within Kyrgyz territory, forming enclave areas (see Appendix, Figure B). The water issue in Uzbekistan becomes a critical matter that could potentially trigger regional conflicts due to the interconnectedness of the Central Asian republics through water bodies. Moreover, the entirety of Uzbekistan's two main rivers' riverbeds lies beyond the country's current borders, further escalating the potential for water-related disputes in Central Asia. These factors contribute to a geopolitical dynamic in the region, leading to the following hypotheses in our study (

Figure 2).

Therefore, our study delves into the intricate nature of water resource distribution, recognizing its geopolitical ramifications. We examine the perspectives of various Uzbek and foreign experts as expressed in television and internet publications. The prevailing consensus suggests that recent years have witnessed a geopolitical landscape shaped by the distribution of water resources, posing security challenges between Uzbekistan and its neighboring states. It is evident that water-related disputes will impede cooperation and partnership across various domains between Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries. Hence, this study seeks to comprehensively explore the complexities surrounding water distribution to gain a deeper understanding of the issue.

3. Objective Framework

Numerous scholarly inquiries have employed the renowned security theory propagated by the Copenhagen School to analyze the multifaceted dimensions of contentious issues, including the one under investigation (Glass, 2010; Thapliyal, 2011; Hadian & Rigi, 2019; Stępka, 2022; Mohapatra, 2023). The Copenhagen School posits that security is not an inherent state but a socially constructed concept, emerging through subjective interactions and discursive practices among influential actors who propose threat definitions and relevant audiences who accord recognition to such definitions. It signifies a deliberate process of constructing security (Buzan et al., 1998; Stępka, 2022). Therefore, considering the uncharted landscape concerning the political geography of water conflict in the Amudarya and Syrdarya watersheds of Uzbekistan, this study aims to provide comprehensive illumination on this intricate phenomenon. Various factors contribute to the complex water predicament in Uzbekistan, necessitating careful scrutiny. Firstly, Uzbekistan possesses the highest population and the most rapid growth rate among its regional counterparts (refer to

Table 1). Secondly, the country's increasing agricultural diversification and burgeoning industrialization, particularly evident in the oasis regions west of Tashkent, exert mounting pressure on resolving the water crisis faced by Uzbekistan and its neighboring states.

Significantly, the issue of water resources and security in Uzbekistan assumes paramount sensitivity in the region due to its potential to significantly impact intergovernmental relations and interstate dynamics (

www.awwa.org, www.uzsuv.uz,

www.un.org, and

www.worldwaterweek.org). Accordingly, this study adopts a theoretical perspective to explore the intricate interplay between water and security, while also considering potential measures that Uzbekistan and its neighboring nations can undertake to ensure regional water security. Geopolitics serves as the overarching theme permeating this investigation (Vinogradov, 1996; Zakhirova, 2013). The study delves into the trajectories of two pivotal rivers in Central Asia, namely the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya. Considering that the Amu Darya traverses the territories of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, and the Syr Darya courses through Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, the water predicament transcends mere national confines and assumes a regional dimension (Pianciola, 2020). In this regard, the Syr Darya assumes critical importance as the primary water source for Uzbekistan, thus possessing the potential to ignite a regional conflict involving Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The protracted water conflicts between Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries serve as evidence of the precarious precipice on which the rapidly evolving Central Asian region teeters, verging on a geopolitical impasse. The study also explores the notion of resource scarcity, commonly known as the "threat of own resources," which constitutes the underlying trigger for the geopolitical challenges plaguing Central Asia (Karakuzu, 2017; Safranchuk et al., 2022).

4. Literature Review

The impact of natural resource abundance or scarcity on regional and international relations is widely acknowledged. Water, as a crucial resource, is no exception, and its scarcity often leads to conflicts between nations, as evident in Uzbekistan and its surrounding regions. Previous studies have explored water conflicts through critical and classical theories (Dungen, 1985; Kreamer, 2012; Mohapatra, 2023). Classical literature addresses the concept of "resource scarcity" (Barnett & Morse, 1963; Barbier, 1989; Jayasuriya, 2015), and the term "water scarcity" is commonly used in contemporary scientific articles (Kummu et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022). Water scarcity triggers disputes over river flow control, infrastructure development such as hydropower plants and dams, and competition among economic sectors reliant on shared water resources. Consequently, the issue of water scarcity assumes a geopolitical nature, involving power struggles and control over water resources (Ocakli & Artman, 2023). However, it is important to note that water scarcity does not always lead to conflict; it can also create opportunities for alliances between countries, as observed in the theory of complex interdependence (Nye, 1987). Michel Foucault's concept of the intersection of power, knowledge, and space (1984) can further contribute to improving the water situation in Uzbekistan and neighboring countries. United Nations reports on global water development are considered authoritative sources. The 2020 report indicates an annual one percent increase in water demand, leaving 1.6 billion people facing water scarcity due to inadequate distribution infrastructure (

www.un.org). Population growth, globalization-induced changes in consumption patterns, and economic development contribute to water scarcity, which is projected to reach forty percent by 2030 (

www.reliefweb.int, 2022/03/21). Different regions experience water shortages and increased flooding, as evidenced by numerous floods reported by the UN, highlighting water-related problems as significant risks (

www.unstats.un.org: SDG Report-2022). Considering the theoretical and analytical data mentioned above, it becomes apparent that the water problem presents a regional and global security challenge, with deep-rooted crises that can exacerbate other issues. Water scarcity, as a form of resource scarcity, has the potential to trigger major conflicts on a regional or global scale (Rheinbay et al., 2021). In light of the theoretical and scientific perspectives, the geopolitical implications of the water problem in Uzbekistan can be summarized as follows:

Water is both an essential resource for Uzbekistan and a shared resource with neighboring countries, influencing relations between post-Soviet republics in Central Asia. Security challenges in the region arise from climate change, global warming, the shrinking of the Aral Sea, declining water levels in major rivers such as the Amudarya and Syrdarya, water scarcity, population growth, and economic competition. Analyzing these interconnected problems necessitates a comprehensive consideration of factors such as agriculture, economy, production, precipitation, temperature, and climate change in the region. Climate change studies highlight the impact of global warming on the shrinking of Antarctic ice and the volume of water during hot and dry periods, emphasizing the potential for regional conflicts arising from decreased water volume (Hamidov et al., 2018). Water-related conflicts leading to armed conflicts have been documented in specific regions (Erdonov & Mustayev, 2022), and academic articles present case studies on unequal water use (Peña-Ramos et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Disputes over water resources or ownership have been identified as underlying causes of conflicts in areas such as Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, and others (Daoudy, 2008; Mueller et al., 2021; Kibaroglu & Scheumann, 2013). Water pollution, in addition to climate change, poses a threat to human health and can potentially lead to social or political conflicts in regions like Uzbekistan that share water resources with neighboring countries. While there are currently no disputes specifically related to water pollution, existing pollution in Uzbekistan's rivers contributes to soil salinization and impacts agricultural practices. Therefore, water pollution in shared rivers cannot be confined to a single area; it has the potential to escalate into social, environmental, and regional conflicts.

Territorial claims, such as water conflicts between Israel and Jordan or Iraq and Turkey, have been studied in the context of the water problem (Elmusa, 1995; Ferragina, 2008;

www.climate-diplomacy.org, 2021). Similar cases exist in Central Asia, prompting this research to provide a geopolitical analysis of how the water problem threatens peace in the region. Resource dependence or scarcity in countries holds geopolitical significance (Dogan, 2021; Nygaard, 2022), and the legacy of the forced resource-sharing system from the USSR era remains geopolitically relevant in Central Asia. Conflicts may arise when one republic desires to build infrastructure like dams, reservoirs, or hydroelectric power plants that are perceived as potential threats by another republic. At the international level, studies suggest that China's dam construction in Tibet harms India, highlighting power struggles and inadequacies between the two countries (Miao et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2019). Such issues are seen as a quest for international political hegemony. The pressure exerted on another country or region sharing the same resource is another aspect highlighted in this context (Boehmer-Christiansen, 1996; Global Risk Report, 2023). Geopolitical considerations of "hegemony" have been applied to the water problem in North Africa (Baconi, 2018) and West Asia (Khalid, 2020). Negotiations based on supply and demand have been proposed as potential solutions for maintaining peace and cooperation (Dore et al., 2010). Central Asia also exhibits signs of resource-based hegemony, with Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan possessing more gas and oil resources while Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have more water resources. There is a tendency to exert pressure using their respective resources (Sehring, 2019). However, the current system of resource sharing, including electricity and some rivers or reservoirs left over from the USSR, limits immediate tensions. Nevertheless, the potential for water conflicts remains as local conflicts have already occurred in the region under the pretext of water (Gleason, 1997), negatively impacting people's security and ultimately threatening regional stability.

5. Methodology

To ensure a comprehensive analysis from a political geography perspective, this study employs a mixed methodology that integrates historical analysis, critical observation, and data analysis from international and national reports. The study delves into the historical context of water-related issues in Uzbekistan, with a particular emphasis on the legacy of resource sharing inherited from the Soviet era. By examining past situations and conflicts concerning water resources between Uzbekistan and neighboring countries, such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the research aims to provide insights into the political geography of water-related conflicts in the region. This historical analysis offers a foundation for understanding the territorial dynamics, geopolitical relationships, and historical agreements that have shaped the current water problem. A critical approach is adopted to analyze the water problem in Uzbekistan and its geopolitical implications within the realm of political geography. This involves a meticulous examination of existing international and national reports on Uzbekistan and Central Asia, including annual reports published by international organizations. The study critically evaluates the data, identifying patterns, trends, and discrepancies through a political geography lens. Through this critical observation, the research aims to uncover the underlying political factors, power dynamics, and territorial disputes that contribute to the water problem. Furthermore, it explores the geopolitical relationships, strategic interests, and potential conflicts between countries in the region concerning water resources.

To enhance the empirical foundation of the study within the context of political geography, various sources of data are incorporated. Official statistical websites such as

www.stat.uz, www.stat.kg,

www.gov.kz, www.dataportals.org, and

www.stat.gov.tm, provide valuable data on water resources, population, agriculture, and other relevant factors. The collected data is subjected to rigorous analysis, utilizing political geography perspectives, to identify key spatial patterns, territorial dynamics, and correlations. Statistical analysis techniques are employed to derive meaningful insights, and visual representations such as maps, charts, and graphs may be utilized to present the findings in a clear and comprehensive manner, highlighting the political geography dimensions of the water problem. By synergizing historical analysis, critical observation from a political geography perspective, and data analysis, this study aims to provide a holistic understanding of the water problem in Uzbekistan within the context of political geography. Moreover, it seeks to elucidate the regional implications of this issue and its potential impact on security, territorial disputes, and geopolitical relationships in Central Asia. The utilization of a mixed methodology ensures a robust and multifaceted investigation, enhancing the scholarly rigor and enriching the findings of the research within the realm of political geography.

6. Geopolitical Perspective: Water Issues Series

The water crisis in Central Asia presents significant challenges from a political geography perspective. This analysis combines historical research, critical observation, and data analysis to delve into the complex dynamics surrounding water-related conflicts in the region. With a concise and cutting-edge approach, this study examines the available information. Central Asia is grappling with a severe water crisis, characterized by an average annual water supply per person below 1,000 cubic meters (

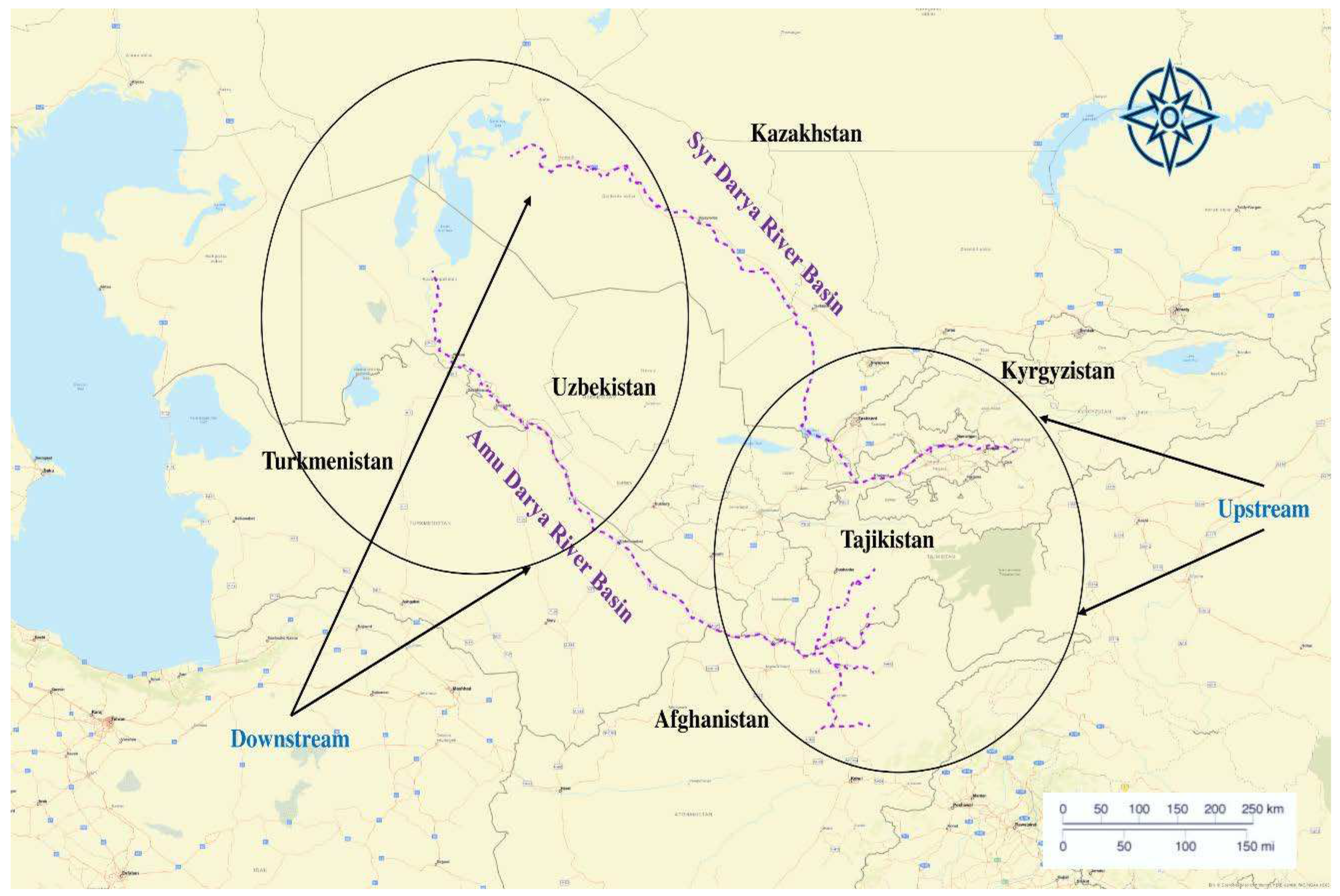

www.un.org). The projected population growth exceeding 100 million by 2050 further exacerbates water scarcity (Michanan, 2016). The catastrophic decline of the Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake globally, underscores the profound impact of irrigation practices, climate change, and other contributing factors on the region (Yanan et al., 2022). The economic ramifications of the water crisis are substantial, potentially amounting to 1.6% of the region's total gross domestic product annually, with agriculture being the most affected sector. Inefficient irrigation practices, outdated technology, and climate change contribute to significant water losses, estimated to be as high as 60%. Projections indicate a further 20-30% decrease in water resources by the end of the century, intensifying the crisis (Michanan, 2016). Transboundary water conflicts between “Upstream” and “Downstream” countries over the Amudarya and Syrdarya Rivers add to the challenges faced by Central Asia (

Figure 3). Uzbekistan heavily relies on these rivers as its primary water sources, but their riverbeds extend beyond its administrative boundaries, emphasizing the complexities of shared water utilization in the region. The Aral Sea Basin, historically dependent on these rivers for water supply, is located within the territories of Karakalpakstan and Kazakhstan, highlighting the pivotal role of water resources in socio-economic development. Also, glaciers in the mountainous regions of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan also contribute to the water supply (Rakhmatullaev et al., 2013).

Understanding the total annual volume of water resources, approximately 116 km

3, with 90% originating from the Amudarya and Syrdarya Rivers, is crucial in terms of political geography. Groundwater resources account for approximately 43.49 km

3, and water usage is primarily allocated to agriculture, with lesser portions for industry, households, services, and other purposes. Efforts to reform water resource management and regulatory systems following the dissolution of the USSR have been limited, with insufficient funding and declining expertise in the water sector. The region’s water management has only been partially implemented, affecting up to 15% of water management. Historical and political changes have influenced water-related relations between Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries. Water conflicts emerged during the first administration of Uzbekistan, with the construction of hydropower plants in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan politicizing the situation. Border demarcation disputes with neighboring countries, particularly Kyrgyzstan, have added complexity to the issue. Kyrgyzstan’s skepticism towards regional water cooperation institutions and the construction of large hydropower plants have impacted water-related relations. Inadequate regional cooperation has resulted in significant annual losses, highlighting the urgent need for water scarcity mitigation measures and desalination (“National Water Law of Central Asian Countries,”

www.cawater-info.net).

The unequal distribution of water resources in the region reflects both natural conditions and policies implemented during the Soviet era. Large-scale cotton cultivation in Uzbekistan and the demand for expanded agricultural land prompted the construction of dams, reservoirs, and canals. Inefficient water management and the delayed establishment of a dedicated water ministry during the Soviet Era have led to adverse consequences. Since 2017, political changes in Uzbekistan have brought renewed focus to water issues through bilateral and multilateral cooperation (

www.gazeta.uz, 2023). Reforms in agriculture, land, and water management are underway in Central Asia. While regulation in agricultural production and land tenure has declined compared to the Soviet Era, the state continues to play a vital role in ensuring food and water security. However, this strict regulatory system has deterred private investments, particularly in infrastructure. The water crisis in Central Asia, especially in Uzbekistan, presents significant challenges from a geopolitical standpoint. The region’s severe water scarcity, compounded by the decline of the Aral Sea and inefficient irrigation practices, necessitates a comprehensive understanding of transboundary water conflicts, border demarcation disputes, and large hydropower plant construction. Recent political changes in Uzbekistan have prompted a renewed focus on addressing water issues through cooperation, reforms, and attracting private investments. Recognizing the historical tradition of state control in water resource management is essential to comprehend the multifaceted challenges faced by Uzbekistan and the broader Central Asian region.

7. Water Distribution

The geopolitical scope of the water issue in Central Asia revolves around the distribution and management of water resources, particularly in relation to the region’s two major rivers. The Amu Darya, 2,400 km long, rises at the confluence of the Panj and Vakhsh rivers in Tajikistan's Pamir Mountains. It crosses the territories of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan before flowing into the Aral Sea. The Amu Darya is fed by various sources, including rivers, glaciers, and snow. About 1,000 glaciers contribute to its water supply. Most notably, the Fedchenko Glacier, the largest mountain valley glacier on Earth, and the Hindu Kush Mountains in Afghanistan feed the Amu Darya. Similarly, the Syr Darya flows westward, southwestward, and then northwestward through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan, eventually emptying into the Aral Sea. The river basin covers an area of about 462,000 km², with a catchment area of 219,000 km². The lower reaches of the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya are located in the republics of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan (Hamidov, et al., 2018. Understanding these geographic facts is critical to the geopolitical analysis of water resources in the region. An important geopolitical issue concerns the study of water distribution between Uzbekistan and its neighboring republics. It is worth noting that there is growing concern about "resource hegemony" or "resource dependence" in some regions, which adds to the dynamics of water conflicts between the post-Soviet Central Asian republics. In addition to water conflicts, there is a unique interdependence among the Central Asian republics for other resources (such as gas, minerals, etc.). Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan depend on Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan for gas supplies, while they rely mainly on Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan for water supplies (Mohapatra, 2023). This interdependence creates a delicate balance that can threaten peace and cooperation in the region when it comes to water distribution. Analytical information suggests that water-related disputes have the potential to trigger conflicts in the political and social spheres. Therefore, water resources alone can pose a significant security risk in the region.

Central Asia’s natural geography, impacted by climate change, further exacerbates water challenges. The region has experienced major population shifts and changes in economic development, resulting in increased water demand. Uzbekistan, in particular, has faced water scarcity despite its population growth and economic reforms. The combination of a food crisis, economic competition, and rapid development reforms is increasing demand for water. This leads to an implicit “resource hegemony” dynamic in which Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as upstream countries, occupy a “hydro-hegemony” position vis-à-vis Uzbekistan. Given these dynamics, the geopolitical landscape of the region can be understood by considering the importance of upstream and downstream locations. This highlights the potential risk of water conflicts between Uzbekistan and its neighbors, especially if Uzbekistan diversifies its agriculture. It is critical to manage these geopolitical complexities to ensure effective water management and promote regional stability.

8. Geopolitical Landscape of Water Distribution

8.1. Upstream Countries: The Agro-Hydro Dynamics

In the realm of agriculture, Kyrgyzstan stands out for its specialization in cultivating a diverse range of crops, including tobacco, cotton, potatoes, vegetables, grapes, fruits, and berries. The agricultural sector plays a significant role in the country, contributing to 20% of the gross domestic product and employing approximately 40% of the labor force. However, the agricultural prosperity of Kyrgyzstan hinges upon a crucial resource—water. Positioned in the headwaters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, Kyrgyzstan relies on these lifelines for 90% of its water supply. Alas, global climate change has taken its toll, with 16% of Kyrgyzstan's glacier area melting away. This stark reality undermines the notion of “unrestricted sharing” with Uzbekistan when it comes to water distribution. Tajikistan, another upstream country, primarily focuses on the cultivation of wheat, rice, and barley. This sector accounts for 22.6% of the country's GDP and employs 45.7% of its population. Similar to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan's agricultural success is inextricably linked to water availability. Positioned at the headwaters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the republic depends on these water bodies for 90% of its water resources. Unfortunately, the impact of global climate change is evident here as well, with 30% of Tajikistan’s glacier area melting away. This disheartening reality undermines any notions of a harmonious “sharing” strategy with Uzbekistan regarding water distribution (refer to

Table 1).

8.2. Downstream Countries: The Water-Dependent Realities

Kazakhstan, a downstream country, predominantly focuses on cultivating cereal crops, with wheat occupying the foremost position in terms of cultivated acreage. Barley, cotton, sunflower seeds, and rice also feature prominently. Agriculture contributes 5.03% to the country’s gross domestic product, with around 30% of the population deriving income from agricultural employment. Kazakhstan, too, understands that agricultural development hinges upon water resources. Positioned downstream, it relies on the Syr Darya River for sustenance. Consequently, the notion of “unrestricted sharing” of water in the region is rendered impractical. Turkmenistan's agricultural landscape thrives on the cultivation of cotton, wheat, corn, grapes, almonds, vegetables, oranges, pomegranates, figs, olives, and subtropical fruits. This sector significantly contributes to the country's gross domestic product, generating 11.7% and employing 40% of the labor force. Given the arid climate, irrigation becomes crucial for cultivating virtually all arable areas. As a downstream country, Turkmenistan, too, depends on the Amu Darya River for water supply. Consequently, the concept of “unrestricted sharing” of water resources proves unfeasible in the region. Afghanistan’s agricultural sector primarily focuses on growing wheat and cereals, making up a notable 33.48% of the country's GDP, although precise labor statistics are unknown. As a downstream country, Afghanistan heavily relies on water supply from the Amu Darya River. Understanding the vital role water plays in agricultural development, Afghanistan recognizes that water availability is pivotal.

Consequently, any prospects of “unrestricted sharing” in water distribution within the region become unrealistic. Uzbekistan, positioned downstream, specializes in the cultivation of cotton, wheat, barley, and corn. This agricultural sector significantly contributes to the country's GDP, accounting for approximately 25%, while employing 26% of the labor force. Uzbekistan, too, acknowledges the indisputable fact that water is an indispensable component of agricultural growth. With 90% of its water sourced from the lower reaches of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the strategy of "welcomed sharing" water resources in the region has proven futile (refer to

Table 1). The aforementioned points serve to illuminate the underlying disagreements and disputes concerning water distribution between Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries. While delving into the intricacies of water management across various regions within Uzbekistan is a worthy pursuit, for brevity's sake, it remains beyond the scope of this discussion.

9. Examination of Water Distribution

9.1. Water Management in the Syr Darya Basin

The preceding section’s analysis sheds light on the geographical attributes and significance of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers. During the Soviet Union’s “reign over” Central Asia, the recognition of these rivers’ water resources for agriculture was crucial, and a centralized approach to water distribution effectively mitigated conflicts within the river basins. However, following the post-Soviet independence of the republics, the dynamics surrounding water distribution shifted, necessitating a comprehensive examination within a broader geopolitical context. The Syr Darya basin in Central Asia provides valuable insights into the geopolitical research landscape concerning water distribution. Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan exert control over several significant reservoirs along the Syr Darya (

www.un.org). Within Uzbekistan, the Farkhod Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP) assumes a pivotal role. Situated near the Tajikistan border in the Bekobod district of the Tashkent region, the plant diverts water from the Syr Darya River to the Tashkent Region and the Farhod Reservoir through the Farhod Canal. Additionally, the Dostlik Canal conveys water to the semi-arid regions of the Jizzakh Region, known as “Mirzachul.” Uzbekistan’s Bekobod spans an area of 0.76 thousand km² with an irrigated area of 37.9 thousand hectares, while Mirzachul covers 10 thousand km² with an irrigated area of 205 thousand hectares. The Shardara Reservoir, located in the middle stream of the Syr Darya, spans the right bank in the South Kazakhstan region and the Jizzakh region of Uzbekistan. On the left bank of the middle stream, the Kyzylkum main channel distributes water to the new lands in Mirzachul (Jizzakh, Uzbekistan) and the irrigated lands in South Kazakhstan. In Tajikistan, the Khujand region primarily houses the Kayraqkum Water Reservoir and Kayraqkum HPP. A small portion extends into Uzbekistan's Fergana region to the west. Water from the Kayraqkum reservoir is distributed to the Fergana Valley and the northern districts of Tajikistan, with a permanent irrigated area surpassing 475 thousand hectares. Consequently, the Syr Darya River, from its inception to its terminus at the Aral Sea, intricately weaves a complex network of tributaries and channels. Human intervention, including the construction and operation of large dams, reservoirs, canals, and collectors across most tributaries, has significantly altered the river’s natural flow. Recent monitoring data demonstrates a substantial decline in the average annual water flow at Khujand (Tajikistan) to 476 m³/s and in the upper section at Gazali (Kazakhstan) to 158 m³/s.

9.2. Water Management in the Amu Darya Basin

The Amu Darya basin, comprising Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan, hosts the largest hydropower installations, namely the Norak Reservoir and Norak Power Plant. Unlike the Syr Darya, the Amu Darya basin possesses significant hydropower resources, with a total capacity of 63.2 million kilowatts. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are the primary consumers of water from the Amu River. Population growth and agricultural diversification are expected to increase the river's importance. However, the Amu River's glaciers, which serve as its source, are rapidly melting due to global warming and climate change, leading to water scarcity issues. Afghanistan's construction of the “Kushtepa” canal diverts one-third of Amu Darya's water, exacerbating water scarcity in Uzbekistan. Similar to the Syr Darya, the Amu Darya River system exhibits diverse tributaries and channels before reaching the Aral Sea. Predictions indicate a potential 20% reduction in the river's source glaciers by the 2030s, along with temperature increases of up to 30 degrees by the 2050s (

www.un.org). Glacier decline in Tajikistan ranges from 20-30%, while Afghanistan experiences a more significant decline of 50-70%. These changes have substantial implications for water availability, with projections suggesting a 20% decrease in Amu Darya’s water flow by the 2080s, potentially impacting up to 50% of cultivated land within the basin.

The geopolitical analysis of water distribution in Central Asia, focusing on the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, emphasizes the intricate interplay between water resources, infrastructure development, climate change, and regional politics. Water security, transboundary water management, and resource dependencies intersect in this context, shaping the region's geopolitical dynamics. Effective management of water resources and resolution of water-related disputes necessitate comprehensive approaches rooted in geopolitical theories such as hydro-hegemony, critical geopolitics, and resource diplomacy. By understanding and applying these theories and concepts, policymakers can navigate the complex water challenges in Central Asia and promote regional stability.

9.3. Controversies: “Resource hegemony” or “-nationalism”

Hence, controversies surrounding “resource hegemony” and “resource nationalism” have emerged in the political geography of Central Asia, particularly among Uzbekistan and its neighboring countries: Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. These disputes primarily centered around water resources and hydropower projects posed significant challenges to regional stability and this requires comprehensive analysis for viable solutions (Scientific Research Institute of Irrigation and Water Problems, 2022).

One of the disputes involved Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, with a focus on the construction of the Rogun Dam project. Under the leadership of President Karimov, Uzbekistan implemented measures such as ceasing gas supplies and restricting material transportation to Tajikistan in response to the project. Uzbekistan expressed concerns about the dam's seismic vulnerability, which could lead to catastrophic flooding in the region. In contrast, Tajikistan considered the Rogun Dam crucial for achieving energy independence and socioeconomic development. This situation highlighted a scenario of “resource hegemony” where Tajikistan seeks to assert control over water resources. However, the construction of the Rogun Dam might pose significant risks to Uzbekistan, including agricultural devastation and adverse environmental consequences. To address this issue, cooperation and recognition of shared obligations are essential. Employing “soft power” diplomacy, emphasizing resource exchange, water supply, and electricity, can facilitate a resolution to these challenges. Sustained dialogue and negotiations between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, with a deep understanding of each other’s concerns, can lead to a mutually beneficial outcome (Jalilov, 2011).

Another controversy arose between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan due to the construction of the Qambar-Ota hydropower plant in Kyrgyzstan. The project's impact on the Syrdarya River, which runs through the Fergana Valley, has strained relations between the two countries. Uzbekistan objected to the plant, resulting in a reduction of water flow and the suspension of gas exports to Kyrgyzstan. This situation escalated to heightened border controls and military deployments, which began to ease following a change in Uzbekistan’s government in 2017. Similar to the Uzbek-Tajik dispute, concerns about the dam’s location in an earthquake-prone area and potential disruptions to agriculture intensify tensions. Geopolitical hegemony was at play, with Kyrgyzstan leveraging its relationship with Russia against Uzbekistan. Resolving this issue requires recognizing shared obligations and fostering cooperation. The interdependence of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan in terms of water, gas, and electricity necessitates diplomatic efforts focused on soft power. The progress made through agreements and ongoing dialogues between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan indicates positive steps toward addressing these challenges.

Water trade between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan was also subject to economic, political, and environmental factors. Both countries heavily rely on the Amudarya River for water supply, leading to prolonged negotiations (Alimjanov, 2020). The dispute revolved around the utilization and management of Amudarya’s waters, including concerns about upstream dam construction and its impact on Uzbekistan's water supply. Turkmenistan aimed to develop hydropower and expand agricultural production, further complicating the negotiations. Encouragingly, recent years have witnessed positive developments in water negotiations between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, with joint water management committees and restoration projects initiated for the preservation of wetlands and ecosystems. However, achieving sustainable and equitable water usage remains a critical challenge that necessitates ongoing efforts and diplomatic engagement. Thus, the geopolitical dynamics surrounding water resources and hydropower projects in Central Asia require careful consideration, innovative approaches, and extensive cooperation. By understanding the complexities and interdependencies at play, policymakers can work towards resolving disputes, ensuring regional stability, and fostering sustainable development.

9.4. Importance of Regional Cooperation

The geopolitical and geographic image of Central Asia is deeply intertwined with the water issue, requiring meaningful and coherent cooperation among the countries in the region. The governments of Central Asia play a vital role in ensuring food and water security and acting as stabilizing forces. With ongoing agricultural, land, and water reforms, Afghanistan, following the rise of the Taliban, has initiated dialogues with the Central Asian republics, expressing its concerns about the water issue. This highlights the emergence of water scarcity as a common problem among the six countries. Experts argue that these nations lack the financial and technical expertise necessary to effectively address water scarcity on their own. Therefore, collaborative efforts among governments are essential in finding solutions to the water problem. Economic cooperation between countries becomes a pressing concern as it not only helps address common issues but also prevents the exploitation of minor problems, making it an important cohesive force among the republics. Recent endeavors, such as the meeting of foreign ministers of Central Asian countries, demonstrate efforts to understand the specific aspects of economic cooperation. To establish a pragmatic and stable system of cooperation among the leaders of Central Asian nations, fostering regional cooperation through institutions dedicated to nature conservation and water resource management is imperative. With the construction of large-scale reservoirs, ensuring their safety becomes paramount. Establishing a regional organization responsible for the safety and utilization of these water facilities represents a timely and progressive step forward. It is important to note that the water issue goes beyond borders for Uzbekistan, making cooperation with Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and other Central Asian countries crucial, particularly for Afghanistan. While Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are the upstream of main rivers, the water supply in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan is dwindling, especially during the peak water usage season in summer. Therefore, solving this problem through cooperation is of utmost importance.

Table 2 provides insights into the factors and solutions for the water issue in Central Asia. These factors play a significant role in addressing collaboration challenges and require attention. Analyzing per capita water consumption and understanding water usage patterns are crucial for achieving equitable distribution. Assessing the needs of each country, considering population sizes and water requirements, allows for fair allocation. Addressing unequal water distribution in agriculture is essential and calls for policies promoting efficient techniques and technologies. Modernizing water distribution mechanisms through technology and considering climate change projections optimizes resource allocation. Resolving territorial disputes over shared water resources is crucial and can be facilitated through diplomacy and adherence to international water law. Additionally, increasing common interests fosters cooperation by prioritizing shared goals like climate change adaptation and sustainable development. Addressing and resolving these factors effectively enable the management of water’s geopolitical nature, promoting equitable governance, sustainable development, and cooperation among Central Asian states. Strengthening regional cooperation becomes imperative to prevent conflicts, maintain regional security, and ensure the sustainable development of Central Asia. By working together, Central Asian countries can overcome water-related challenges and pave the way for a prosperous and cooperative future.

10. Conclusion

To conclude, this study provided an analysis of the political geography of water issues in the Amu and Syrdarya basins in Central Asia. The findings highlight the complex geopolitical landscape surrounding water resources and emphasize the need for enhanced regional cooperation to address water scarcity and mitigate conflicts. The study contributes to the field by employing classical geopolitical theories and critical approaches to gain valuable insights into the water issue in the region. Based on the research, several recommendations are proposed to improve cooperation on water resources in Central Asia. These include the development of new technical solutions, continuing reforms in the water sector, the introduction of appropriate incentives, and significant reforms in education and scientific research. Implementing these recommendations will strengthen water resource management, promote sustainable development, and reduce the risk of water-related conflicts in the region. Addressing the complex water problems in Central Asia requires a basin-based approach to water management, fostering cooperation and equitable sharing of resources. Mechanisms for cooperative management should be established among countries sharing the same river basins, and transboundary water agreements and joint management institutions can ensure sustainable water use while defusing conflicts. Diplomacy and multilateral forums play a crucial role in facilitating dialogue and negotiations among Central Asian states.

The study also emphasized the importance of adopting an environmental security framework to address interconnected environmental, social, and political dimensions associated with water conflicts. Sustainable development practices, ecosystem protection, and considering environmental factors in policymaking enable comprehensive solutions. Furthermore, regional integration initiatives and platforms like the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) program can promote cooperation, strengthen economic interdependence, and reduce the likelihood of conflict. Inclusive and participatory governance approaches that engage diverse stakeholders enhance transparency, accountability, and overall water governance effectiveness. By implementing these globally recognized ideal proposals rooted in theories of political geography, Central Asian countries can navigate the complexities of water conflicts and advance sustainable and cooperative water management. These approaches contribute to regional stability, socio-economic development, and the broader global agenda of water security and environmental sustainability. The study's novelty lies in its comprehensive analysis of the political, social, and human geography of water issues in Central Asia, offering valuable insights and practical solutions for policymakers and stakeholders in the region.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback and constructive comments, which greatly enhanced the quality and clarity of this manuscript. Their expertise and guidance have been instrumental in shaping this research and contributing to its scholarly rigor. The authors also acknowledge the efforts of the journal's editorial team for their support throughout the publication process.

Declaration

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- American Water Works Association [Internet]. 2022. Available from: www.awwa.org.

- AWWA [Internet]. 2023, Available from: www.awwa.org.

- Baconi T. Testing the water: How water scarcity could destabilise the Middle East and North Africa [Internet]. European Council on Foreign Relations; 2018 Nov 13. Available from: www.ecfr.eu.

- Barbier EB. Economics, natural resources scarcity and development conventional and alternative views. Earthscan Publications; 1989., pp.45-67.

- Barnett HJ, Morse C. Scarcity and growth: the economics of resource availability. John Hopkins Press; 1963., pp.98-109.

- Boehmer-Christiansen S. Political pressure in the formation of scientific consensus. Energy & Environment. 1996 Dec;7(4):365-75.

- Brauch HG. Introduction: facing global environmental change and sectorialization of security. InFacing Global Environmental Change: Environmental, Human, Energy, Food, Health and Water Security Concepts 2009 (pp. 21-42). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Buzan B, Wæver O, De Wilde J. Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers; 1998., pp.74-145.

- Central Asian Water Information [Internet]. National Water Law of Central Asian Countries. Available from: www.cawater-info.net.

- Daoudy M. Asymmetric power: Negotiating water in the Euphrates and Tigris. International Negotiation. 2009 Jan 1;14(2):361-91.

- Data Portals [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.dataportals.org.

- Dogan E, Majeed MT, Luni T. Analyzing the impacts of geopolitical risk and economic uncertainty on natural resources rents. Resources Policy. 2021 Aug 1;72:102056. [CrossRef]

- Dore J, Robinson J, Smith DM, editors. Negotiate: reaching agreements over water. IUCN; 2010. Ch.3, pp.37-45.

- Earle A, Cascão AE, Hansson S, Jägerskog A, Swain A, Öjendal J. Transboundary water management and the climate change debate. Routledge; 2015 May 26., pp.170-176.

- Elmusa SS. The Jordan-Israel Water Agreement: a model or an exception?. Journal of Palestine Studies. 1995 Apr 1;24(3):63-73. [CrossRef]

- Erdonov MN, Mustayev QR. Utilization of transborder subresources in central Asian countries: problems and solutions. Economics and society [In Uzbek: Markaziy Osiyo mamlakatlarida transchegaraviy suvresurslaridan foydalanish: muammo va yechimlar. Экoнoмика и сoциум.] 2022(11-1 (102)):74-80.

- Eurasianet.org [Internet]. 2023 Apr 04. Available from: www.eurasianet.org.

- Ferragina E. The Effect of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on the Water Resources of the Jordan River Basin. Global Environment. 2008 Jan 1;1(2):152-70. [CrossRef]

- Foucault M, Rabinow P. Space, knowledge, and power. Material Culture. In Paul Rabinow (Ed.) The Foucault Reader, New York: Pantheon, 1984:239–56.

- Gazeta.uz [Internet]. 2022 Mar 16. Available from: www.gazeta.uz.

- Gazeta.uz [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.gazeta.uz.

- Glass N. The water crisis in Yemen: causes, consequences and solutions. Global Majority E- Journal. 2010 Jun;1(1):17-30.

- Gleason G. Independence and decolonization in Central Asia. Asian Perspective. 1997, 1:223-46.

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.gov.kz.

- Hadian N, Rigi H. Securitization and international challenges on water in south Asia: A case study of Pakistan. Strategic Studies Quarterly. 2019 Dec 21;22(85):135-58. https://dorl.net/dor/20.1001.1.17350727.1398.22.85.6.2.

- Hamidov A, Helming K, Balla D. Impact of agricultural land use in Central Asia: a review. Agronomy for sustainable development. 2016, 36:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Ho S, Neng Q, Yifei Y. The Role of Ideas in the China–India Water Dispute. The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 2019 Jun 1;12(2):263-94. [CrossRef]

- Holmatov B, Lautze J, Kazbekov J. Tributary-level transboundary water law in the Syr Darya: overlooked stories of practical water cooperation. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics. 2016 Dec;16(6):873-907. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Duan W, Chen Y, Zou S, Kayumba PM, Qin J. Exploring the changes and driving forces of water footprint in Central Asia: A global trade assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022 Nov 15;375:134062. [CrossRef]

- Jalilov SM. Impact of Rogun dam on downstream Uzbekistan agriculture (Doctoral dissertation, North Dakota State University).2011 Vol 3(8):161-166.

- Jayasuriya RT. Natural resource scarcity-classical to contemporary views. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research. 2015 Oct 1;7(4):221-45. [CrossRef]

- Karakuzu T. Hegemony and energy resources: example of Central Asia. VUZF Review. 2017(2):108-123.

- Keohane RO, Nye JS. Power and interdependence revisited. International organization. 1987;41(4):725-53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2706764.

- Khalid M. Geopolitics of Water Conflict in West Asia: The Tigris-Euphrates Basin. Geopolitics. 2020 Oct;4(1):2-6.

- Kibaroglu A, Scheumann W. Evolution of transboundary politics in the Euphrates-Tigris river system: new perspectives and political challenges. Global Governance. 2013;19:279. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24526371.

- Kreamer DK. The past, present, and future of water conflict and international security. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education. 2012 Dec;149(1):87-95. [CrossRef]

- Kummu M, Guillaume JH, de Moel H, Eisner S, Flörke M, Porkka M, Siebert S, Veldkamp TI, Ward PJ. The world’s road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Scientific reports. 2016 Dec 9;6(1):38495. [CrossRef]

- Miao C, Borthwick A, Liu H, Liu J. China’s Policy on Dams at the Crossroads: Removal or Further Construction? Water [Internet] 2015;7(12):2349–57. [CrossRef]

- Michanan J, Dewri R, Rutherford MJ. GreenC5: An adaptive, energy-aware collection for green software development. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems. 2017, 13:42-60. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1122.

- Mohapatra NK. Geopolitics of water securitisation in Central Asia. GeoJournal. 2023 Feb;88(1):897-916. [CrossRef]

- Molle F, Mollinga PP, Wester P. Hydraulic bureaucracies and the hydraulic mission: Flows of water, flows of power. Water alternatives. 2009;2(3):328-49.

- Mueller A, Detges A, Pohl B, Reuter MH, Rochowski L, Volkholz J, Woertz E. Climate change, water and future cooperation and development in the Euphrates-Tigris basin. ResearchGate/Geoscience/Report. 2021 Nov., pp.38-53.

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.stat.kg.

- Nygaard A. The geopolitical risk and strategic uncertainty of green growth after the Ukraine invasion: How the circular economy can decrease the market power of and resource dependency on critical minerals. Circular Economy and Sustainability. 2022 Jul 2:1-28. [CrossRef]

- Ocakli B, Artman V. Nationalism and Violence in Central Asia [Internet]. Oxus Society; 2023. Available from: www.oxussociety.org.

- Peña-Ramos JA, Bagus P, Fursova D. Water Conflicts in Central Asia: Some Recommendations on the Non-Conflictual Use of Water. Sustainability 2021;13:3479. [CrossRef]

- Pianciola N. The Benefits of Marginality: The Great Famine around the Aral Sea, 1930–1934. Nationalities Papers. Cambridge University Press; 2020;48(3):513–29. [CrossRef]

- Rakhmatullaev S, Huneau F, Celle-Jeanton H, Le Coustumer P, Motelica-Heino M, Bakiev M. Water reservoirs, irrigation and sedimentation in Central Asia: a first-cut assessment for Uzbekistan. Environmental earth sciences. 2013 Feb;68:985-98. [CrossRef]

- Reed, D. (Ed.). (2017). Water, security, and US foreign policy. Taylor & Francis, Part II, pp.35-39.

- Regional Collaboration by Water Utilities. AWWA Policy Statement. 2019, (online article) at www.awwa.org.

- ReliefWeb [Internet]. 2022 Mar 21. Available from: www.reliefweb.int.

- Rheinbay J, Mayer S, Wesch S, Vinke K. A threat to regional stability: Water and conflict in Central Asia. URL: https://peacelab. blog/2021/04/a-threat-to-regional-stability-water-andconflict-in- central-asia (data 02.11. 21). 2021.

- Safranchuk IA, Zhornist VM, Nesmashnyi AD, Chernov DN. The Dilemma of Middlepowermanship in Central Asia: Prospects for Hegemony. Russia in global politics. 2022 Jul(3)., pp.116-133. [CrossRef]

- Salman SM, Uprety K. Conflict and cooperation on South Asia's international rivers: A legal perspective. BRILL; 2021 Oct 18.: Chapter 3, pp.195-203.

- Sehring J. Review of Power and water in Central Asia, Routledge, 2018, by Filippo Menga [Internet]. Water Alternatives; 2019, Available from: www.water-alternatives.org.

- State Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Uzbekistan [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.stat.uz.

- State Committee on Statistics of Turkmenistan [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.stat.gov.tm.

- Stępka M. The Copenhagen school and beyond. A closer look at securitisation theory. InIdentifying Security Logics in the EU Policy Discourse: The “Migration Crisis” and the EU 2022 Feb 10 (pp. 17-31). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Thapliyal S. Water security or security of water? A conceptual analysis. India Quarterly. 2011 Mar;67(1):19-35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45073036.

- UNECE & UNESCAP. Strengthening Cooperation for Rational and Efficient Use of Water and Energy Resources in Central Asia. United Nations: New York; 2023. Water 2050 website.

- United Nations [Internet]. 2022. Available from: www.un.org.

- United Nations [Internet]. Available from: www.un.org.

- United Nations Statistics Division [Internet]. SDG Report-2022, www.unstats.un.org.

- Uzsuv [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.uzsuv.uz.

- Van den Dungen P. Peace Research and the Search for Peace: Some Critical Observations. International Journal on World Peace. 1985 Jul 1:35-52.

- Vinogradov S. Transboundary water resources in the former Soviet Union: Between conflict and cooperation. Natural Resources Journal. 1996 Apr 1:393-415. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24885806.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Fang G, Li Z, Liu Y. The growing water crisis in Central Asia and the driving forces behind it. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022 Dec 10;378:134574. [CrossRef]

- Wolf AT. Hydropolitics along the Jordan River: Scarce water and its impact on the Arab-Israeli conflict. United Nations University Press; 1995, Vol. 99, Part 3, pp.87-100.

- World Water Week [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.worldwaterweek.org.

- Xiao R, Jiang M, Li Z, He X. New insights into the 2020 Sardoba dam failure in Uzbekistan from Earth observation. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. 2022 Mar 1;107:102705. [CrossRef]

- Zaharna RS. A humanity-centered vision of soft power for public diplomacy’s global mandate. Journal of Public Diplomacy. 2021;1(2):27-48 . [CrossRef]

- Zakhirova L. The international politics of water security in Central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies. 2013 Dec 1;65(10):1994-2013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).