Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background:

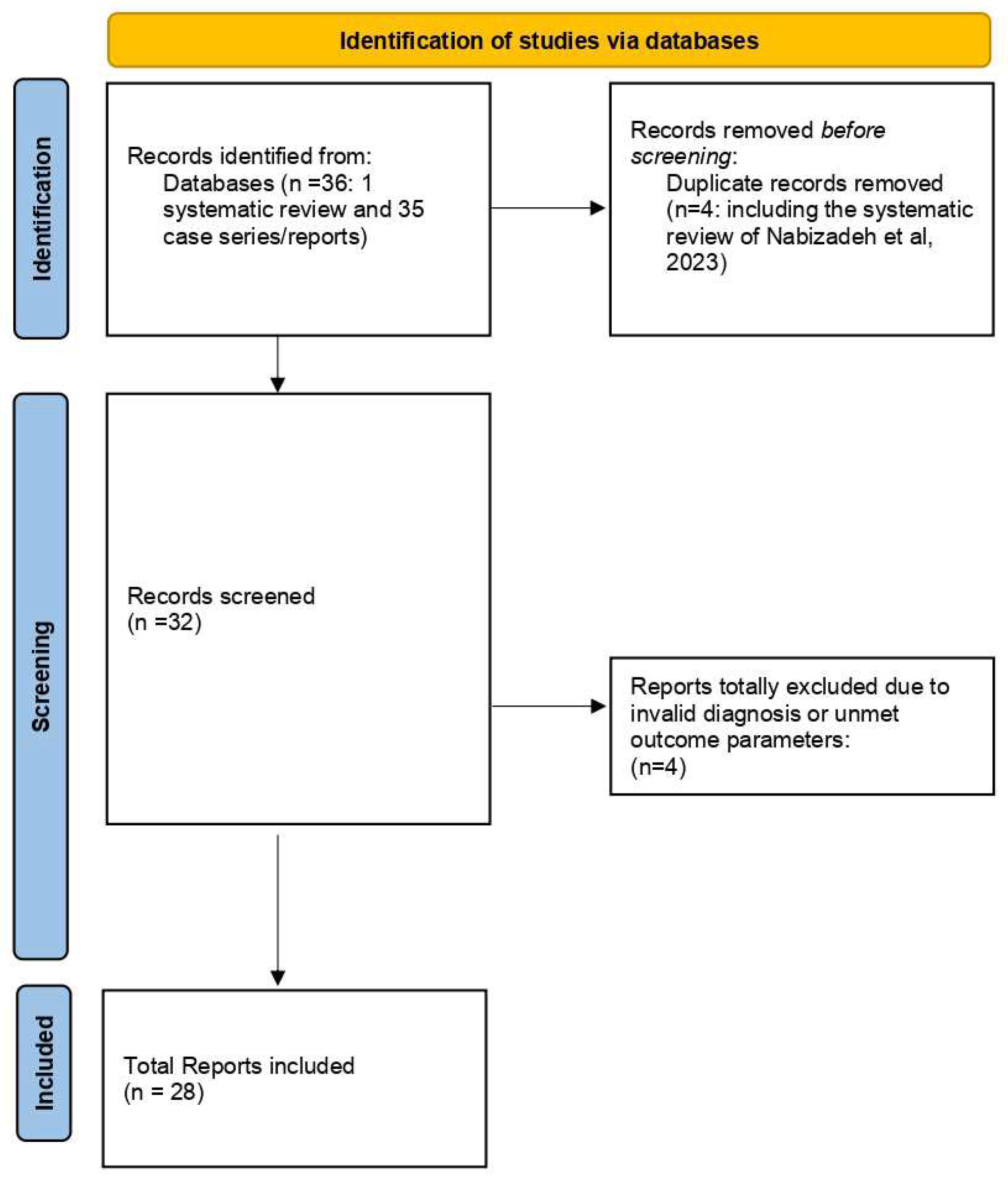

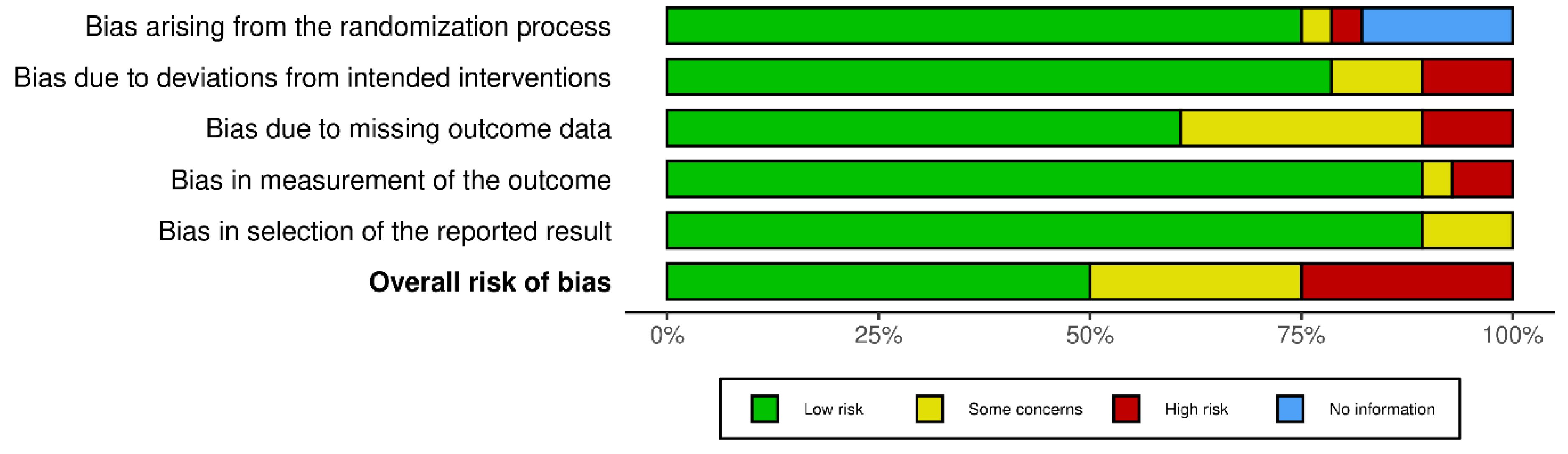

Methodology:

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Search

Outcome Parameters:

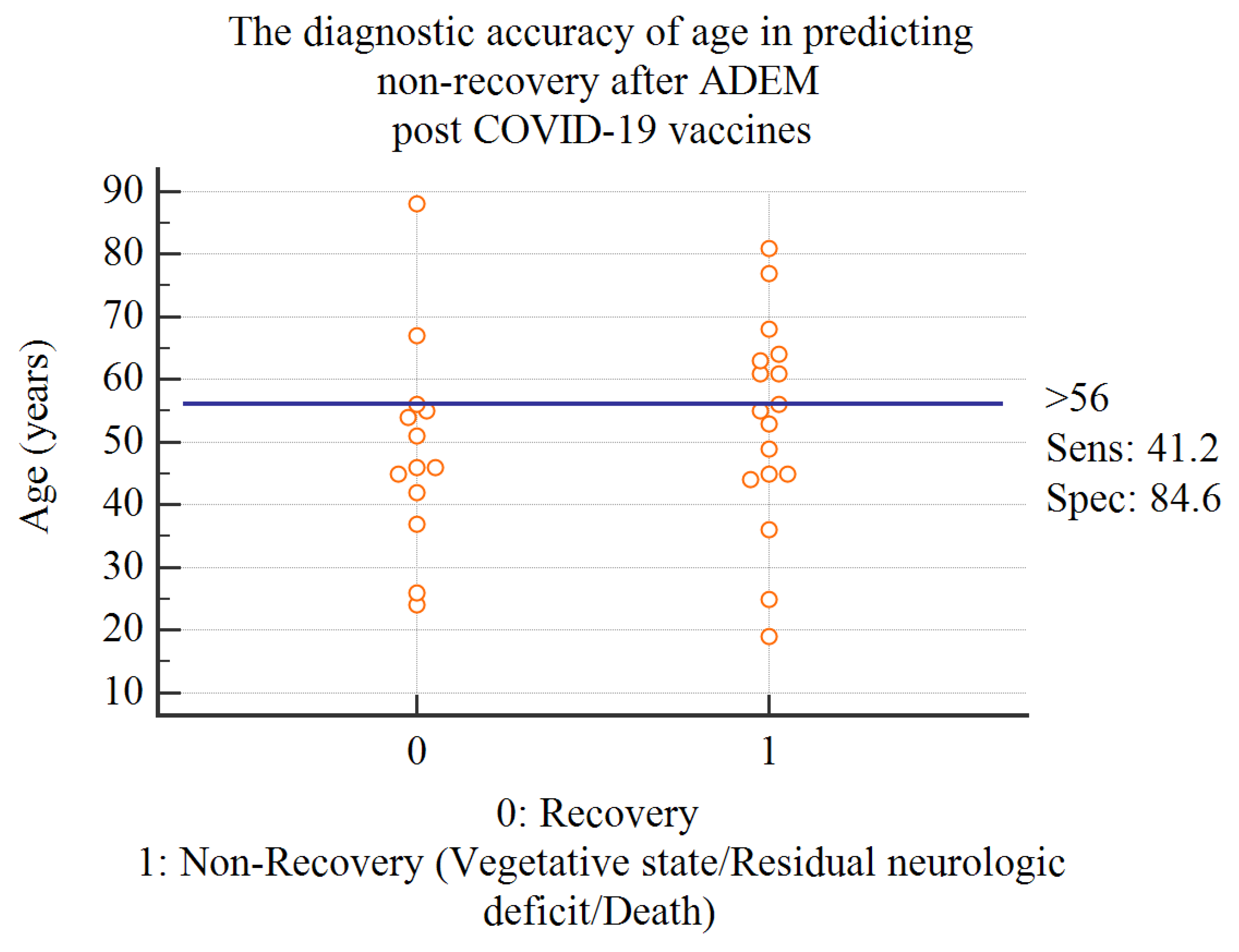

Statistical Analysis:

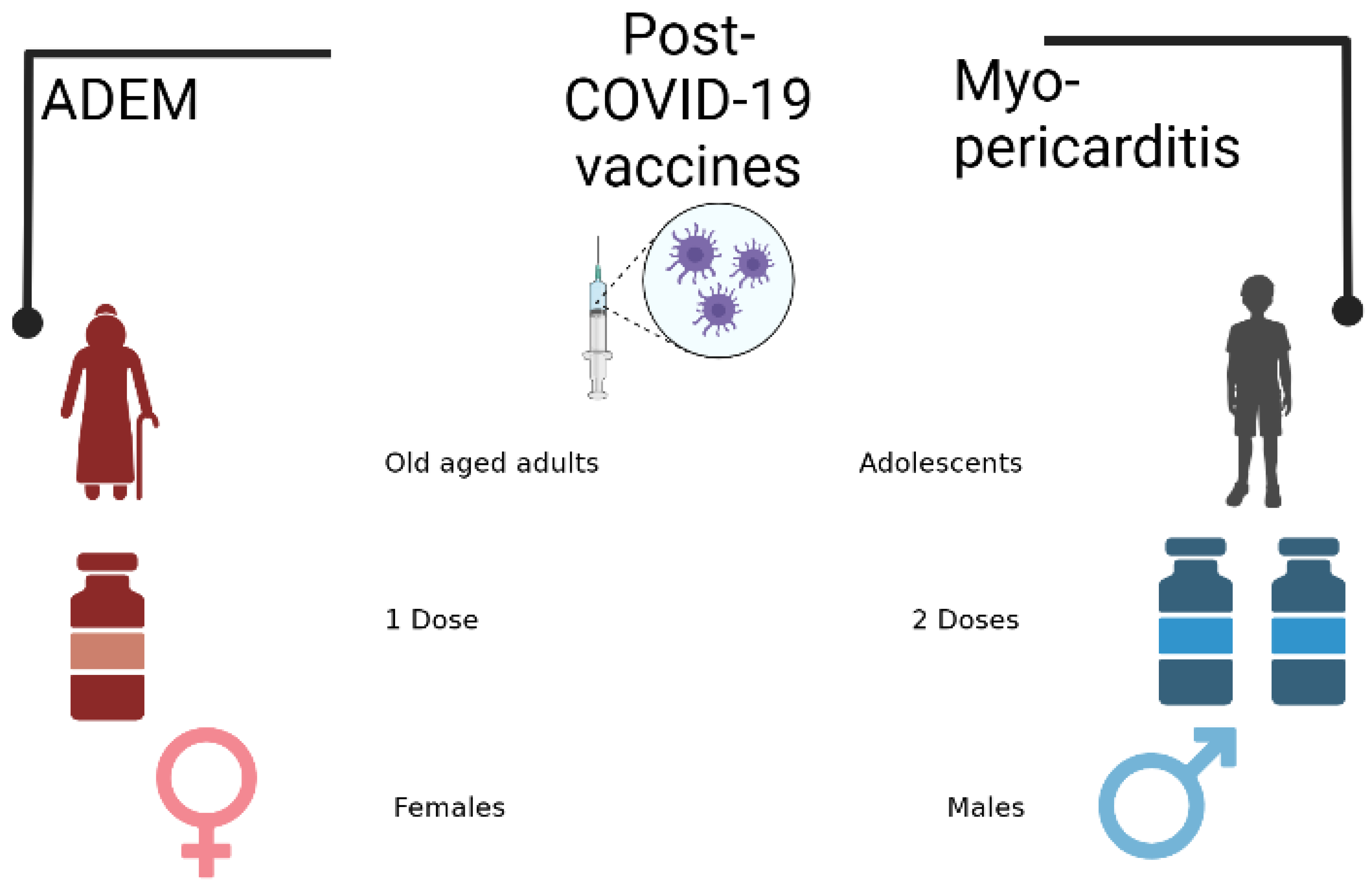

Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ad26.COV2. | Janssen vaccine |

| ADEM | Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis |

| BBB | Blood brain Barrier |

| BBIBP-CorV | Sinopharm |

| BCSFB | Blood cerebrospinal fluid barrier |

| BNT162b2 | Pfizer Biontech vaccine |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CoronaVac | Sinovac |

| Covax | Coronavirus vaccine initiative |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CTLA4 | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 |

| DCL | Disturbed Conscious level |

| Gam-COVID-Vac | Sputnik Vaccine |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LL | Lower Limb |

| MP | Methylprednisolone |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic acid |

| mRNA-1273 | Moderna Spikevax vaccine |

| NR | Not reported |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death ligand 1 |

| PP | Plasmapheresis |

| VAERS | Vaccine adverse events Reporting system |

References

- Li, M.; Yuan, J.; Lv, G.; Brown, J.; Jiang, X.; Lu, Z.K. Myocarditis and Pericarditis following COVID-19 Vaccination: Inequalities in Age and Vaccine Types. J Pers Med 2021, 11, 1106. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/11/11/1106. [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.T.; Dionne, A.; Muniz, J.C.; McHugh, K.E.; Portman, M.A.; Lambert, L.M.; et al. Clinically Suspected Myocarditis Temporally Related to COVID-19 Vaccination in Adolescents and Young Adults: Suspected Myocarditis After COVID-19 Vaccination. Circulation 2022, 145, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, R.J.M.; Nelson, M.R.; Collins Jr, L.C.; Spooner, C.; Hemann, B.A.; Gibbs, B.T.; et al. A Prospective Study of the Incidence of Myocarditis/Pericarditis and New Onset Cardiac Symptoms following Smallpox and Influenza Vaccination. Horwitz MS, editor. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118283. Available online: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, N.; Nokura, K.; Zettsu, T.; Koga, H.; Tachi, M.; Terada, M.; et al. Neurologic Complications Associated with Influenza Vaccination: Two Adult Cases. Intern Med 2003, 42, 191–194. Available online: http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/internalmedicine1992/42/2/42_2_191/_article. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, W.; Cordato, D.J.; Kehdi, E.; Masters, L.T.; Dedousis, C. Post-vaccination encephalomyelitis: Literature review and illustrative case. J Clin Neurosci 2008, 15, 1315–1322. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0967586808001896. [CrossRef]

- Sejvar, J.J. Neurologic Adverse Events Associated With Smallpox Vaccination in the United States, 2002-2004. JAMA 2005, 294, 2744. Available online: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.294.21.2744. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.; Pahud, B.A.; Vellozzi, C.; Donofrio, P.D.; Dekker, C.L.; Halsey, N.; et al. Causality assessment of serious neurologic adverse events following 2009 H1N1 vaccination. Vaccine 2011, 29, 8302–8308. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21893148. [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Noori, M.; Rahmani, S.; Hosseini, H. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review. J Clin Neurosci 2023, 111, 57–70. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0967586823000668. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Koh, J.; Takahashi, M.; Niwa, M.; Ito, H. A case of anti-MOG antibody-positive ADEM following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 3513–3514. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10072-022-06019-6. [CrossRef]

- Ballout, A.A.; Babaie, A.; Kolesnik, M.; Li, J.Y.; Hameed, N.; Waldman, G.; et al. A Single-Health System Case Series of New-Onset CNS Inflammatory Disorders Temporally Associated With mRNA-Based SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 796882. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35280277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Quliti, K.; Qureshi, A.; Quadri, M.; Abdulhameed, B.; Alanazi, A.; Alhujeily, R. Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis Post-COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diseases 2022, 10, 13. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9721/10/1/13. [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, F.; Iranpour, P.; Haseli, S.; Poursadeghfard, M.; Yarmahmoodi, F. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) after SARS- CoV-2 vaccination: A case report. Radiol case reports 2022, 17, 1789–1793. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35355527. [CrossRef]

- Permezel, F.; Borojevic, B.; Lau, S.; de Boer, H.H. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following recent Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2022, 18, 74–79. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12024-021-00440-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogrig, A.; Janes, F.; Gigli, G.L.; Curcio, F.; Del Negro, I.; D’Agostini, S.; et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2021, 208, 106839. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0303846721003681. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.R.; Timmermans, V.M.; Dakakni, T. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis After SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Am J Case Rep 2022, 23, e936574. Available online: https://www.amjcaserep.com/abstract/index/idArt/936574. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Ren, L. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: A case report. Acta Neurol Belg 2022, 122, 793–795. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13760-021-01608-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, A.M.; Monti, G.; Amidei, S.; Costa, M.; Vaghi, L.; Devetak, M.; et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IGG) antibody in a patient with recent vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. J Neurol Sci 2021, 429, 118167. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022510X21008637. [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, L.G.; Perea Cossio, J.E.; Luis, M.B.; Tamagnini, F.; Paguay Mejia, D.A.; Solarz, H.; et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: A case report. Brain, Behav Immun - Heal 2022, 20, 100439. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666354622000291. [CrossRef]

- Kania, K.; Ambrosius, W.; Tokarz Kupczyk, E.; Kozubski, W. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in a patient vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2021, 8, 2000–2003. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acn3.51447. [CrossRef]

- Nagaratnam, S.A.; Ferdi, A.C.; Leaney, J.; Lee, R.L.K.; Hwang, Y.T.; Heard, R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis with bilateral optic neuritis following ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Neurol 2022, 22, 54. Available online: https://bmcneurol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12883-022-02575-8. [CrossRef]

- Ozgen Kenangil, G.; Ari, B.C.; Guler, C.; Demir, M.K. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis-like presentation after an inactivated coronavirus vaccine. Acta Neurol Belg 2021, 121, 1089–1091. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34018145. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, V.; Bellucci, G.; Romano, A.; Bozzao, A.; Salvetti, M. ADEM after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine: A case report. Mult Scler J 2022, 28, 1151–1154. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13524585211040222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumoli, L.; Vescio, V.; Pirritano, D.; Russo, E.; Bosco, D. ADEM anti-MOG antibody-positive after SARS-CoV2 vaccination. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 763–766. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10072-021-05761-7. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Ogaki, K.; Nakamura, R.; Kado, E.; Nakajima, S.; Kurita, N.; et al. An 88-year-old woman with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following messenger ribonucleic acid-based COVID-19 vaccination. eNeurologicalSci 2021, 25, 100381. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34841097. [CrossRef]

- Ancau, M.; Liesche-Starnecker, F.; Niederschweiberer, J.; Krieg, S.M.; Zimmer, C.; Lingg, C.; et al. Case Series: Acute Hemorrhagic Encephalomyelitis After SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Front Neurol 2022, 12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.820049/full. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maramattom, B.V.; Lotlikar, R.S.; Sukumaran, S. Central nervous system adverse events after ChAdOx1 vaccination. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 3503–3507. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35275317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netravathi, M.; Dhamija, K.; Gupta, M.; Tamborska, A.; Nalini, A.; Holla, V.V.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine associated demyelination & its association with MOG antibody. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022, 60, 103739. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211034822002541. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.; Patel, T.H.; Meadows, I.; Ozdemir, B. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM) After Consecutive Exposures to Mycoplasma and COVID Vaccine: A Case Report. Cureus 2022. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/93548-acute-disseminated-encephalomyelitis-adem-after-consecutive-exposures-to-mycoplasma-and-covid-vaccine-a-case-report. [CrossRef]

- Sazgarnejad, S.; Kordipour, V. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: A case report Case presentation: 2022;1–9.

- Gustavsen, S.; Nordling, M.M.; Weglewski, A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following the COVID-19 vaccine Ad26.COV2.S, a case report. Bull Natl Res Cent 2023, 47, 5. Available online: https://bnrc.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42269-023-00981-7. [CrossRef]

- Bastide, L.; Perrotta, G.; Lolli, V.; Mathey, C.; Vierasu, O.I.; Goldman, S.; et al. Atypical acute disseminated encephalomyelitis with systemic inflammation after a first dose of AztraZaneca COVID-19 vaccine. A case report. Front Neurol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimkar, S.V.; Yelne, P.; Gaidhane, S.A.; Kumar, S.; Acharya, S.; Gemnani, R.R. Fatal Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis Post-COVID-19 Vaccination: A Rare Case Report. Cureus 2022. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/126502-fatal-acute-disseminated-encephalomyelitis-post-covid-19-vaccination-a-rare-case-report. [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Batra, P.K.; Gupta, P. Post COVID-19 Vaccination Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis: A Case Report. Curr Med Imaging Rev 2023, 19, 91–95. Available online: https://www.eurekaselect.com/204488/article. [CrossRef]

- Raknuzzaman. Post Covid19 Vaccination Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis: A Case Report in Bangladesh. Int J Med Sci Clin Res Stud.

- Lohmann, L.; Glaser, F.; Möddel, G.; Lünemann, J.D.; Wiendl, H.; Klotz, L. Severe disease exacerbation after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination unmasks suspected multiple sclerosis as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A case report. BMC Neurol 2022, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M.; Ray, I.; Mascarenhas, D.; Kunal, S.; Sachdeva, R.A.; Ish, P. Myocarditis post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A systematic review. QJM Int. J. Med. 2023, 116, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabie, N.; Lichtman, A.H.; Padera, R. T cell checkpoint regulators in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2019, 115, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M.P.; Agalliu, D.; Cutforth, T. Hello from the Other Side: How Autoantibodies Circumvent the Blood–Brain Barrier in Autoimmune Encephalitis. Front Immunol 2017, 8. Available online: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00442/full. [CrossRef]

- Spindler, K.R.; Hsu, T.-H. Viral disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Trends Microbiol 2012, 20, 282–290. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22564250. [CrossRef]

- No Title.

- Wu, X.; Wu, W.; Pan, W.; Wu, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.-L. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy: An underrecognized clinicoradiologic disorder. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 792578. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25873770. [CrossRef]

- Falahi, S.; Kenarkoohi, A. Sex and gender differences in the outcome of patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 151–152. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.26243. [CrossRef]

| Report | Age | Main Vaccine Mechanism | Subtype of Vaccine | Interval between Vaccine and Sequelae (days) | Dose Number |

Gender | Clinical Picture | Treatment Received | Recovery/Residual Lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Raknuzzaman n.d, 2021) | 55 | 1 | mRNA (unspecified subtype) | 21 | NR | 2 | Headache, somnolence, fluctuating alertness, and orientation consistent with delirium and convulsions | MP then oral steroids | full recovery |

| (Mousa et al. 2022) | 44 | 1 | mRNA (unspecified subtype) | 6 | 1 | 1 | Blurred vision, DCL, lower limb weakness, impaired sensation, urine retention. | IV, oral steroids and plasmapheresis | Bilateral optic atrophy |

| (Shimizu et al. 2021) | 88 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 29 | 2 | 1 | impaired consciousness and gaze-evoked nystagmus | Improved on pulse IV methylprednisolone for 3 days | Progressive improvement on day 31 and day 66 |

| (Kits et al. 2022) | 53 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Confusion and unconsciousness (GCS of 7), agitation, snoring, anisocoria, and reduced voluntary movements in the left arm and leg | MP, IVIG, PP | Remained in vegetative state |

| (Ahmad, Timmermans, and Dakakni 2022) | 61 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 70 | 1 | 1 | Generalized weakness and altered mental status | steroids and IVIG | Required tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube due to generalized weakness |

| (Miyamoto et al. 2022) | 54 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 12 | 2 | 1 | Fever, urine retention, headache, DCL, facial palsy. | MP, IVIG, PP | Well recovered |

| (Lohmann et al. 2022) | 68 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 23 | 1 | 1 | Exacerbating of preexisting paraparesis. | Improved on IV steroids and plasmapheresis. Also received eculizumab. | Residual paraparesis |

| (Vogrig et al. 2021) | 56 | 1 | BNT162b2 | 14 | 1 | 1 | unsteadiness of gait, predominantly on the left side, followed by clumsiness of left arm. | Steroids | Improvement in gait stability, being able to walk without aid. Mild dysmetria and intention tremor of the left upper limb were still present |

| (Kania et al. 2021) | 19 | 1 | mRNA-1273 | 14 | 1 | 1 | Severe headache, fever (37.5°C), back and neck pain, nausea and vomiting and urinary retention | MP | Residual mild headache |

| (Ballout et al. 2022) | 81 | 1 | mRNA-1273 | 13 | 1 | 2 | Coma | MP, IVIG, PP | Death |

| (Garg, Batra, and Gupta 2023) | 67 | 2 | ChAdOX1 nCoV-19 | 14 | nr | 1 | symptoms of encephalopathy | The patient was given steroids, and a good response was reported. | good response was reported |

| (Nimkar et al. 2022) | 77 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCov-19 | 15 | 1 | 1 | Altered sensorium for four hours, aphasia for four hours, and loss of consciousness within one hour. Altered mental status for 15 days | MP | vegetative state |

| (Bastide et al. 2022) | 49 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 7 | 1 | 1 | flu-like symptoms with fever, fatigue, neck pain, paraesthesia in both legs, up to the chest, Lhermitte's phenomenon and sphincter dysfunction. | MP then readmission/ PP, rituximab | 3 relapses, residual paraparesis |

| (Nagaratnam et al. 2022) | 36 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 14 | 1 | 1 | Reduced visual acuity, headache, fatigue, painful eye movement | Significant improvement on IV and oral steroids. | Mild impairment of visual acuity, one relapse |

| (Maramattom, Lotlikar, and Sukumaran 2022) |

64 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 20 | 2 | 2 | leg stiffness hand parathesia | IVIG | Mild residual paresis |

| 46 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 4 | 1 | 2 | LL weakness | IVIG, MP | Improvement | |

| 42 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 5 | 1 | 1 | headache/photophobia | spontaneous improvement | ||

| (Al-Quliti et al. 2022) | 56 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 10 | 1 | 1 | LL weakness | MP | Complete resolution |

| (Ancau et al. 2022) |

61 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Coma | MP | vegetative state |

| 25 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | Ascending weakness and numbness | MP/plasma exchange | Persistent hemiplegia | |

| 55 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | Tetraparesis | Steroids | Death | |

| (Mumoli et al. 2022) | 45 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 7 | 1 | 2 | Paraparesis and urine retention | MP | Persistence of urine retention |

| (Rinaldi et al. 2022) | 45 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 12 | 1 | 2 | Numbness, decreased visual acuity | - | Complete recovery |

| (Permezel et al. 2022) | 63 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 12 | 1 | 2 | Coma | MP-PP | Death |

| (Netravathi et al. 2022) | 54 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 14 | 1 | 1 | Quadriparesis | MP+PP | NR |

| 35 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | Paraparesis and sensory disturbances | MP | NR | |

| 33 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 14 | 1 | 1 | Persistent sensory disturbances below midthoracic level | MP+PP | NR | |

| 60 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 14 | 2 | 2 | Sensory disturbances, left hemiparesis, memory and behaviour disturbances | MP | NR | |

| 45 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 10 | 1 | 2 | Urine retention, altered sensorium | MP+PP | NR | |

| 52 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 | 35 | 1 | 1 | Slurred speech, swallowing difficulties, paresis involving right side | MP+ rituximab | NR | |

| 20 | 2 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 of the COVAX initiative | 1 | 1 | 1 | Paraparesis and altered sensorium | MP+PP | NR | |

| (Gustavsen, Nordling, and Weglewski 2023) | 31 | 2 | Ad26.COV2. | 28 | 1 | 1 | right-sided weakness and numbness during a three-week period. | MP | complete clinical recovery at the four-month follow-up. |

| (Lazaro et al. 2022) | 26 | 2 | Gam-COVID-Vac (sputnik) | 28 | 1 | 1 | Disorientation/gait imbalance | MP | Complete resolution |

| (Simone et al. 2021) | 51 | 2 | Adenoviral vector vaccine (unspecified) | - | nr | 1 | Paraparesis and urine retention | MP, | Improved |

| (Sazgarnejad and Kordipour 2022) | 45 | 3 | BBIBP-CorV | 28 | 1 | 2 | Acute disorientation and fever | No significant improvement on pulse corticosteroids and plasmapheresis. Also received cyclophosphamide and rituximab. | Residual aphasia and paresis |

| (Cao and Ren 2022) | 24 | 3 | BBIBP-CorV | 14 | 1 | 1 | Memory decline | IVIG | Complete resolution |

| (Yazdanpanah et al. 2022) | 37 | 3 | BBIBP-CorV | 30 | 1 | 2 | Tetraparesis | MP, PP | Improvement of motor function |

| (Ozgen Kenangil et al. 2021) | 46 | 3 | CoronaVac | 30 | 2 | 1 | Seizure | Steroids | Persistence of abnormal MRI |

| Age in patient receiving mRNA vaccines. Mean±SD |

57±19 |

| Age in patients receiving adenoviral vaccines. Mean±SD |

48±14 |

| Age in patients receiving inactivated vaccines. Mean±SD |

38±10 |

| Age in overall patients Mean±SD |

49±16 |

| Sex distribution in the collected cases n (%) |

Female 25(66) |

| Male 13(34) | |

| Major vaccine type distribution in the collected cases n (%) |

mRNA 10(26) |

| Adenoviral vector 24 (63) | |

| Inactivated 4 (11) | |

| Dose distribution in the collected cases n (%) |

1st dose 29 (76) |

| 2nd dose 6 (16) | |

| NR 3 (8) | |

| Interval between vaccination and ADEM Median (min-max) |

14 |

| Major outcome of collected cases n (%) | Complete clinical recovery 14 (37) |

| Residual Neurologic deficit 10 (26) | |

| Vegetative state 4 (11) | |

| Death 3 (8) | |

| NR 7 (18) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).