1. Introduction

Congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) is a constellation of birth defects that can include cataracts, hearing loss, mental retardation, congenital heart defects and growth restriction.1 While the incidence in the United States is relatively low, CRS has been implicated in approximately 100,000 cases per year worldwide.2 While currently uncommon, rubella epidemics can lead to a drastic increase in morbidity for any given population and some countries, such as Japan, are seeing an increase in cases.2 With effective vaccination policies rubella could be eradicated since humans are the only known host. However, lack of formal vaccination programs, vaccine hesitancy or refusal, and missed opportunities by the medical community for vaccine intervention can lead to lack of rubella immunity. An example of this is the 2019 measles outbreak in the United States (US) where a slight decline in vaccine uptake by several close-knit communities led to an outbreak despite the World Health Organization (WHO) having previously declared measles eliminated from the US.3 As vaccine hesitancy increases in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic4, it has become increasingly important to educate patients and identify moments to intervene. One such clinical time point that lends itself as an optimal chance for vaccination intervention is during the postpartum period.

The current practice recommendation in the United States is to measure rubella antibody titers of newly pregnant women and to vaccinate those without immunity with either the Rubella vaccine or the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine postpartum, thereby decreasing the risk of rubella infection in a subsequent pregnancy. An additional postpartum medication routinely administered is Rho(D) immunoglobulin (Rhogam), which is given to Rh negative patients who have delivered a Rh-positive baby to decrease risk of alloimmunization and development of hemolytic disease in a subsequent fetus. Approximately 15% of all deliveries will require administration of Rhogam making this a common medication given on postpartum wards.5 However, there has been concern around postpartum administration of the Rubella vaccine generating suboptimal responses in rhesus (Rh) factor negative patients receiving concomitant administration of Rhogam 6. The concern arises from the possibility that giving a pooled immunoglobulin meant to suppress immune responses at the same time as a vaccine aimed at generating robust responses to viral antigens could theoretically blunt humoral and cellular immune responses.

For this reason, the CDC currently recommends checking for seroconversion several months after concomitant treatment to assure immunity.1 This has resulted in several pharmacological warnings and occasional reluctance to co-administer these injections6,7. Small studies in the early 70’s indicated that coadministering Rhogam and Rubella vaccine does not blunt the immune response to rubella8,9. In one study, 25 patients who were Rubella non-immune and Rh negative received postpartum Rubella vaccine and Rhogam and had the same seroconversion rates as a cohort of 21 rubella non-immune patients receiving Rubella vaccine alone. Even with the limited data supporting the coadministration of Rhogam and Rubella vaccine, the warning to not administer concomitantly still exists. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the serological outcome of co-inoculating patients with both Rhogam and Rubella vaccine postpartum. We hypothesized that seroconversion rates will be similar between groups who were administered concurrent Rubella vaccine and Rhogam to the group receiving Rubella vaccine alone. Overall, our study aims to provide additional data regarding the safety and efficacy of co-inoculation to guide policy changes for improved evidence based clinical care of pregnant patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study was performed within the Mayo Clinic Health System, which is a large network of hospitals serving Southeastern Minnesota. We identified all Rh-negative patients who delivered a neonate between January 1, 2000 to January 1, 2021. This group was then further sub-classified into patients who had a rubella non-immune or rubella equivocal titer during their incident pregnancy. Our cohorts were created by then dividing our population into patients who received Rhogam due to a Rh-positive offspring and into those who did not receive Rhogam due to Rh-negative offspring. Each subgroup was then further queried to see if the subjects had a subsequent pregnancy during which a rubella titer captured.

Inclusion criteria were women ≥18 years of age with Minnesota Research Authorization and a subsequent rubella titer captured during a later pregnancy. Chart review ensured that the timing of vaccinations was during the same postpartum hospitalization and that subsequent titers were available. Additionally, basic characteristics such as age, race and parity were collected for the incident pregnancy as well as the time interval between administration of Rhogam + Rubella vaccine and follow up rubella titer measurements. Ethical committee approval (IRB 21-000667) was obtained prior to initiation of this study and review of any records. All data was recorded in a secure REDCap database.10,11 Per our local laboratory guidelines, we utilized the antibody index during laboratory immunity assessment with >1 being defined as a positive result, >0.7 and <1 as an equivocal result, and <0.7 defined as a negative result.

3. Statistical Analysis

Basic comparisons of maternal features between groups were reported as means and standard deviations or counts and percentages. Significant differences between groups were estimated with Kruskal Wallis tests or chi-squared tests and defined as a p-value ≤0.05. SAS v9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC) was used for analysis.

4. Results

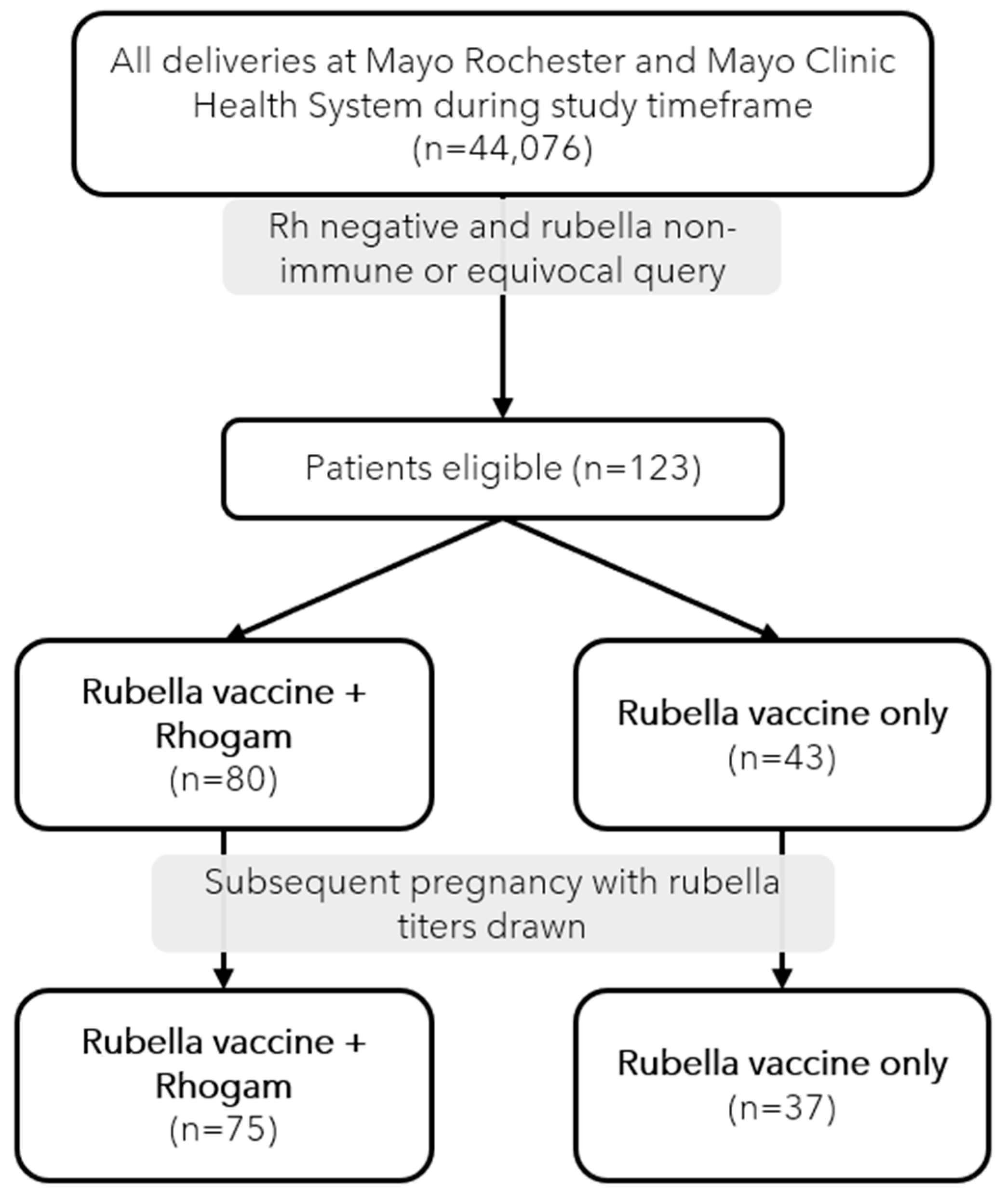

During the study period, 44,076 unique deliveries occurred within our population, out of which 123 (0.28%) were identified as eligible for study inclusion (

Figure 1). In our cohort of 123 subjects, eighty subjects (65%) were identified to be Rh-negative with non-immune or equivocal rubella titers and had delivered a Rh-positive neonate necessitating Rhogam administration. Forty-three subjects (35%) were Rh-negative with non-immune or equivocal rubella titers and delivered a Rh-negative neonate which did not require Rhogam. The maternal demographics of our cohort are displayed and compared in

Table 1. The groups were balanced in terms of age at delivery, race, ethnicity, gestational age, and delivery modality. Subjects receiving Rubella vaccination alone had a significantly higher parity than the Rubella vaccine plus Rhogam group (p=0.01). Nearly 90% of the participants delivered at or after 37 weeks gestation (p=0.21) and had a spontaneous vaginal delivery (p=0.14). All participants received Rubella vaccination during their postpartum hospitalization stay.

Subjects seeking prenatal care for their subsequent pregnancy had their rubella titers measured by a routine blood during the first trimester (

Table 3). In the group that previously received both Rubella vaccination and Rhogam administration postpartum (n=80), 70 were determined to be rubella immune (88%). The cohort receiving only Rubella vaccination (n=43), we observed that 35 subjects (81%) were seropositive for protection, which was not significantly different from those receiving both Rubella vaccine + Rhogam (p=0.36). Twelve percent and 19% of subjects did not show rubella seroconversion in the Rubella vaccine + Rhogam and Rubella vaccine alone groups, respectively. The time interval between the incident pregnancy and follow up rubella titers was significantly different between groups (p = 0.04). Specifically, in those who did not seroconvert, the group receiving Rubella vaccination + Rhogam had a longer interval (2.6 years) to follow up titer measurements compared to 1.0 year for the vaccine only group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella vaccination compared to Rubella vaccination alone.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella vaccination compared to Rubella vaccination alone.

| |

Patient Type |

|

| |

Rubella vaccine + Rhogam

(N=80) |

Rubella vaccine only

(N=43) |

Total

(N=123) |

P-value |

|

Age at Delivery, Mean (SD) |

27.4 (4.63) |

27.9 (4.13) |

27.6 (4.45) |

0.631

|

|

Race, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.092

|

| Non-White |

5 (6.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (4.1%) |

|

| White |

75 (93.8%) |

43 (100.0%) |

118 (95.9%) |

|

|

Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.302

|

| Hispanic or Latino |

2 (2.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (1.6%) |

|

| Not Hispanic or Latino |

78 (97.5%) |

43 (100.0%) |

121 (98.4%) |

|

|

Para, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.012

|

| 0 |

16 (20.0%) |

4 (9.3%) |

20 (16.3%) |

|

| 1 |

39 (48.8%) |

29 (67.4%) |

68 (55.3%) |

|

| 2 |

19 (23.8%) |

4 (9.3%) |

23 (18.7%) |

|

| 3 |

3 (3.8%) |

6 (14.0%) |

9 (7.3%) |

|

| 4+ |

3 (3.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (2.4%) |

|

|

Gestational Age, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.212

|

| 37+ |

74 (92.5%) |

36 (83.7%) |

110 (89.4%) |

|

| 32-36 6/7 |

5 (6.3%) |

6 (14.0%) |

11 (8.9%) |

|

| 24-31 6/7 |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (2.3%) |

1 (0.8%) |

|

| <24 |

1 (1.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (0.8%) |

|

|

Delivery Modality, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.142

|

| C-Section |

19 (23.8%) |

13 (30.2%) |

32 (26.0%) |

|

| Vaginal, Operational |

3 (3.8%) |

5 (11.6%) |

8 (6.5%) |

|

| Vaginal, Spontaneous |

58 (72.5%) |

25 (58.1%) |

83 (67.5%) |

|

|

1Kruskal-Wallis p-value; 2Chi-Square p-value |

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella vaccination compared to Rubella vaccination alone in their subsequent pregnancy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella vaccination compared to Rubella vaccination alone in their subsequent pregnancy.

| |

Patient Type |

|

|

| |

Rubella vaccine + Rhogam (N=75) |

Rubella vaccine only (N=37) |

Total

(N=112) |

P-value |

|

Age at Subsequent Delivery, Mean (SD) |

29.8 (4.64) |

29.6 (4.17) |

29.7 (4.48) |

0.741

|

|

Race, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.112

|

| Non-White |

5 (6.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (4.5%) |

|

| White |

70 (93.3%) |

37 (100.0%) |

107 (95.5%) |

|

|

Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.322

|

| Hispanic or Latino |

2 (2.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (1.8%) |

|

| Not Hispanic or Latino |

73 (97.3%) |

37 (100.0%) |

110 (98.2%) |

|

|

Para, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.522

|

| 1 |

3 (4.0%) |

1 (2.7%) |

4 (3.6%) |

|

| 2 |

51 (68.0%) |

30 (81.1%) |

81 (72.3%) |

|

| 3 |

12 (16.0%) |

4 (10.8%) |

16 (14.3%) |

|

| 4+ |

9 (12.0%) |

2 (5.4%) |

11 (9.8%) |

|

Table 3.

Crossover status of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella compared to Rubella vaccination alone and the interval of time between follow up rubella titer.

Table 3.

Crossover status of participants who received Rhogam + Rubella compared to Rubella vaccination alone and the interval of time between follow up rubella titer.

| |

Patient Type |

|

| |

Rubella vaccine + Rhogam (N=80) |

Rubella Vaccine Only (N=43) |

P-Value |

| Rubella status @ 2nd pregnancy |

|

|

0.361

|

| Negative |

10 (12%) |

8 (19%) |

|

| Positive |

70 (88%) |

35 (81%) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Time interval between incident pregnancy and subsequent rubella titer (years) |

|

|

0.042

|

| Negative, Mean (SD) |

2.6 (1.5) |

1.0 (0.95) |

|

| Positive, Mean (SD) |

2.0 (1.3) |

1.8 (1.1) |

|

5. Discussion

Our data demonstrates that patients receiving both Rhogam and Rubella vaccine during their postpartum hospitalization do not have worse rates of seroconversion to rubella immunity than those who received Rubella vaccine alone. These findings are consistent with smaller studies that found no difference between rubella titers in these two groups during a short time interval8,9. Our study evaluated the difference in real world application after months to years and found no effect of concomitant Rhogam and Rubella vaccine administration on subsequent rubella immunity status. In fact, for the group of subjects receiving both the Rubella vaccine and Rhogam concomitantly, who demonstrated a longer time interval between their incident and subsequent pregnancy, rubella titers remained similar to the rate of seroconversion of the group receiving the Rubella vaccine alone.

Following vaccination, the humoral immune system responds to the purposefully introduced antigen via production antibodies by B cells which have strong specificity and memory.12 This immunological memory allows for the immune system to rapidly respond to antigens in subsequent exposures, thereby limiting the potential negative consequences of pathogenic antigens. The goal of vaccination is to introduce these pathogenic antigens to develop humoral memory and thereby reduce the pathogenicity of various infectious antigens. After mounting an immune response to vaccination, a person’s response can be assessed via measurement of IgG, IgA, IgM, and if applicable IgE. During pregnancy, vertical transmission of immunoglobulin G (IgG) across the placenta confers both fetal and early postnatal protection.13

The immune response of individuals is known to vary and the field of vaccinomics is just beginning to uncover some of the reasons certain sub-groups of patients respond differently to the same vaccine.14 With contributing factors such as genetics, immune status, and medications being used, vaccine response is a complex and poorly understood area of study. While the administration of immunoglobin D (Rhogam) has been suggested6 to blunt the response of Rubella vaccination, there are only small studies that have been completed to date. As more is understood regarding individual response to vaccination, a personalized approach may be used in the future but as of now that level of individualization does not occur.

With the increase in vaccine hesitancy following the COVID-19 pandemic3,4 we believe studies such as this one are important in demonstrating the effectiveness of coadministering two very necessary treatments to avoid both congenital rubella syndrome and alloimmunization complications in future pregnancies. By utilizing the postpartum period as a time point to educate and intervene, the medical community can continue to make strides toward eradication of rubella. While extrapolation of this study’s results to other vaccines given in conjunction with Rhogam are outside of the current scope; it would be prudent to examine other immune response to COVID-19, human papilloma virus (HPV), and varicella vaccination.

This study assessed the seroconversion of patients who received both Rhogam and Rubella vaccination during their postpartum hospitalization. The comparison with the control of the Rh positive/rubella non-immune group of patients allowed us to demonstrate no significant difference in the seroconversion rates of those who received postpartum vaccination with concomitant administration of Rhogam. Our strengths include a large and diverse patient population at a high volume academic medical center with an extensive clinical database of obstetric details. This also to our knowledge is the largest cohort to address this clinical scenario and question to date. The main limitation to our design lies within the retrospective nature of our study. However, all patient data collection followed a strict protocol, and both clinical and laboratory records were retrieved from local well-curated, clinical databases. Another limitation lies within the fact that not all patients routinely have a subsequent pregnancy during which time we could identify whether they have undergone seroconversion from initial vaccination, which is not usually tested otherwise in this population.

6. Conclusions

Rubella infection is a preventable pathogen that can have severe consequences for developing fetus and neonate. Due to hesitancy in administering the Rubella vaccine and Rhogam concomitantly, our aim was to compare the seroconversion rates among patients receiving either Rubella vaccine + Rhogam versus Rubella vaccine alone. Given the findings in this study, that Rhogam administration at the time of Rubella vaccination has no effect on subsequent rubella immunity status, further warnings regarding coadministration of Rhogam with vaccines appear unwarranted. This finding has implications for pregnancy and postpartum administration of other vaccines as well, including COVID-19, varicella, and HPV. Vaccinating susceptible patients postpartum decreases the risk of subsequent infections and improves outcomes for neonates regardless of concomitant immunoglobulin administration. Incorporation of these findings into CDC recommendations is an important step toward hospital policy change to have the greatest impact on patient outcomes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Grant Support

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR002377).

Data Availability

Data can be made available on reasonable request.

References

- McLean, H.Q.; Fiebelkorn, A.P.; Temte, J.L.; Wallace, G.S. Prevention of Measles, Rubella, Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and Mumps, 2013, 2013, 62.

- Lambert, N.; Strebel, P.; Orenstein, W.; Icenogle, J.; Poland, G.A. Rubella. The Lancet 2015, 385, 2297–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambrell, A.; Sundaram, M.; Bednarczyk, R.A. Estimating the number of US children susceptible to measles resulting from COVID-19-related vaccination coverage declines. Vaccine 2022, 40, 4574–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoli, J.M.; Lindley, M.C.; DeSilva, M.B.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020, 69, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, G.S.M.; Keith, L. Utilization of Rh Prophylaxis. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology 1982, 25, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, A.; Wright, D. Potential drug interaction between Rho(D) immune globulin and live virus vaccine. Nurs Womens Health 2014, 18, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RhoGAM and rubella virus vaccine Interactions - Drugs.com [Internet]. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/rhogam-with-rubella-virus-vaccine-2008-2221-2034-0.html?professional=1 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Edgar, W.M.; Hambling, M.H. Rubella vaccination and anti-D immunoglobulin administration in the puerperium. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1977, 84, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroni, E.; Munzinger, J. Postpartum rubella vaccination and anti-D prophylaxis. Br Med J 1975, 2, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, B.L.; Pellicane, A.J.; Tyring, S.K. Vaccine immunology. Dermatol Ther 2009, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmann, T.R.; Marchant, A.; Way, S.S. Vaccination strategies to enhance immunity in neonates. Science 2020, 368, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, N.; Haralambieva, I.; Ovsyannikova, I.; Larrabee, B.; Pankratz, V.S.; Poland, G. Characterization of Humoral and Cellular Immunity to Rubella Vaccine in Four Distinct Cohorts. Immunol Res 2014, 58, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).