1. Introduction

Sustainability encompasses the idea of responsibly managing natural resources, fostering social equity, and ensuring economic prosperity, all while safeguarding the well-being of present and future generations. The inherent challenges can be described as wicked problems, since they involve various stakeholders, are far reaching, complex, difficult to foresee, and occur at the intersection of science, policy, practice, and politics [

1]. Institutional sustainability refers to the policies, regulations, and institutions that contribute to sustainable development and address complex environmental, economic, and social issues [

2,

3,

4]. While sustainability governance initiatives have increased significantly in recent times, doubts persist over whether public institutions can be trusted as legitimate regulators and arbiters of sustainability [

5].

Consumer boycotts are considered a form of political consumerism in which consumers use their purchasing power to attain political, societal, environmental, or ethical objectives [

6]. The literature suggests that consumers may be more willing to engage in consumer activism for sustainability if they trust that a higher institutional authority will observe their actions and act accordingly, by implementing the necessary policies [

7]. However, the role of institutional trust in political consumerism remains ambiguous [

8]. In this context, it is vital to understand the role of institutional trust in consumers’ boycotting behaviour.

This study explores institutional trust as a potential driver for consumers’ boycotts. Besides institutional trust, other factors may affect consumers’ decision to boycott. Thus, our model resorts to political consumerism literature and tests additional potential factors influencing boycotting behaviour.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In the next section we present the theoretical background of the study. The research method is then presented. Next, the results are provided. The paper ends with a discussion of the research findings, as well as the study’s limitations, and directions for future studies.

2. Theoretical background

In recent years, sustainable consumption has emerged as a critical topic in the environmental sustainability and social responsibility literatures [

9,

10]. Citizens and consumers with increasing education and skills associated to the new horizons challenge about the climate change in a global market and globalization, reveal growing concerns about the negative impacts of production and consumption patterns on the environment [

11]. Hence, consumers are increasingly seeking ways to align their purchases with their values [

12] associated to the new emerging challenges across the world.

The anti-consumption movement can be traced back, at least, to the eighteenth century [

13]. Anti-consumption is not a single-dimensional movement. Multiple approaches to anti-consumption coexist and the motivations vary among political, personal, and ethical concerns [

14]. Anti-consumption can be framed under political consumerism, a concept that alludes to consumers expressing their political and ethical values via the purchase of goods or services [

15]. Consumption as voting refers to actions taken by consumers, in response to perceived problems in the market system, being motivated by personal beliefs, values or a moral position, and reflecting a concern for some general good rather than just personal benefits [

16]. Political consumerism can take multiple forms, including boycotting, buycotting, signing petitions, culture jamming and voluntary simplicity [

18,

19].

Research relating anti-consumption with sustainability is limited. Until now, the literature mostly analyses product boycott from a triple-bottom perspective. Pro-sustainability boycott is usually defined as a drive that motivates consumers to refuse to buy or consume products or services that are perceived to have negatively affected social, economic, and/or environmental dimensions of sustainability [

20]. This focus implies a very incomplete vision considering the economic, social, environmental, and institutional challenges reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Grean Deal [

21,

22,

23]. A holistic vision is crucial to align the sustainable practices of consumption, production and distribution and that approach requires a consideration of all the dimensions of sustainability, including the institutional dimension.

The SDGs were adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 in order to provide a comprehensive framework for addressing global challenges and achieving the main goals, sub-goals, indicators and targets to 2030 based on the sustainability concept [

23]. The traditional definition of sustainability from the UN understands the concept as the ability to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [

24] and, according to the UN [

23], and the literature in general, the concept of sustainability includes the standard dimensions of social, environmental and economics, recognizing at the same time, the interdependencies and trade-offs between these pillars.

From an economic perspective, the literature refers that boycotts can significantly impact corporate reputations and financial performance of firms and can compromise the competitive advantages across firms and countries [

25]. Companies facing boycotts often experience negative publicity, damage to their brand image, and a decline in sales [

26]. The literature explored the long-term effects of boycotts on corporate value, finding that sustained boycott activity can result in substantial financial losses for targeted companies [

27]. Understanding these economic consequences can provide insights into the potential influence of boycotts as a driver of sustainable business practices.

From the environmental dimension of sustainability, boycotts could raise awareness and mobilize the public discourse with positive or negative impacts on the environment [

28]. Boycotts play a vital role in raising awareness about environmental issues and stimulating public discourse; however, these processes can impact the environmental sustainability on a positive or/and negative way. On a normal situation, boycotts can capture media attention and spark conversations about environmental concerns [

29]. By drawing public awareness to specific environmental problems, boycotts can create a sense of urgency, mobilize public support, and facilitate broader societal discussions on sustainable practices and policies [

30]. Scientific knowledge about the role of boycotts in shaping public discourse is essential for fostering a collective understanding and commitment to environmental sustainability. However, some negative aspects can also occur. For example, in the agricultural sector there is a real gap of knowledge among consumers and producers [

31]. Sometimes, consumers and the media, without proper knowledge about the complexity of the production process and relative interdependences, spread misinformation negatively impacting the sustainability of the agricultural sector (and related industries and services) and the abandonment of the rural area/industries. For example, in Portugal the media recently emphasized the supposed negative environmental effects of Mirandesa cow production trough methane emissions ("agro-silvo-pastoris” animal systems, from the Mediterranean region) [

32]. This triggered some public institutions to implement restrictive measures and mainstream media in Portugal to develop “news” without proper scientific knowledge. To this regard it is important to refer that IPCC [

33] considers these extensive systems of animal production very important to avoid desertification and climate change, by promoting the environmental, social and economics agricultural activities at the countryside level.

From the social dimension of sustainability boycotts serve as a powerful mechanism for raising awareness about social issues, mobilizing consumers, and allowing firms to focus on social aspects [

34]. Boycotts can draw attention to various social concerns, such as labour rights violations, human rights abuses, and discriminatory practices [

35]. By boycotting companies associated with such issues, consumers signal their support for social justice and contribute to broader societal discussions. Understanding the role of boycotts in raising awareness can shed light on their potential to drive social change. Boycotts have the potential to drive companies towards adopting more social and responsible practices that align with societal expectations [

36]. Companies and international firms often respond by implementing reforms, improving working conditions, and adopting sustainable business practices [

36]. These can lead in the long run to a more powerful engagement among stakeholders and the respective institutions and international agreements.

Nowadays production and consumption due to the increasing globalization is more complex. Involves multiple interactions and participation across countries, industries, legislations, being affected by differentiated political visions of production and consumption, with participants’ different levels of development, infrastructure patterns, policies, and levels of support and subsidies to producers and consumers. This reality requires a more holistic and complete vision of sustainability, one that emphasizes the importance of the institutional context [

2].

The institutional dimension of sustainability emphasizes policy and the importance of governmental intervention for a top-down change in making consumption sustainable by implementing new growth models and changing the context for prosperity and wellbeing [

3,

4]. According to Dos-Santos and Ahmad [

2], the level of support of governments across the world and the respective policies and public measures and legislation allow for differentiated levels of participation and commitment of citizens, consumers, producers, and other supply chains participants. The different patterns and levels of compromising or disagreement among consumers, require specific types of intervention. Hence, stakeholders and institutions play a crucial role in supporting or disapproving boycotts and fostering sustainable business practices. This means that a holistic vision of sustainability needs to consider the macrolevel and institutional factors that directly and indirectly impact the world’s development [

2,

3,

37]. Past research, surprisingly, has paid little attention to the effects of the institutional dimension of sustainability in consumers’ boycotts. This study addresses this research gap by focusing on a specific dimension of institutional sustainability that is institutional trust.

Institutional trust concerns the trust between societal members and public institutions [

5] and has been pointed as a potential driver for institutional sustainability because of the need to balance complex political, economic, institutional, and power relations [

38]. However, the link between institutional trust and political consumerism is ambiguous, since the literature reports conflicting findings. Some studies indicates that political consumerism is positively associated with institutional trust [

39,

40] and others indicate that institutional distrust drives political consumerism [

6,

41].

Public institutions when promoting sustainability often face difficulties in ensuring compliance, because sustainability requires the fundamental change of practices, and behaviour of diverse actors, including consumers [

42]. A major aspect of the problem is translating beliefs into action. Some authors argue that high levels of institutional trust result in voluntary cooperation, meaning that citizens will support the public institution without much resistance and institutions will be expected to perform in the benefit of the citizens, reducing the need for extreme action, such as consumers’ boycotts [

5,

39,

40]. As such, trust in public institutions may be important in addressing complex issues, including the realization of the sustainability agenda [

43]. However, institutional trust beyond a certain high level, makes citizens’ personal contribution appear less relevant, since the state is assumed to take care of the sustainability agenda, regardless of individual activity, thus resulting in less pro-sustainability behaviour out of passivity [

6].

Besides institutional trust, other factors may affect civic engagement. Thus, our model resorts to political consumerism literature and tests additional potential factors influencing boycott behaviour, including gender [

40,

44], age and life-cycle effects [

12,

45], education [

45,

46,

47], interest in politics and level of satisfaction with the political system [

11,

38], generalized trust, meaning the level of faith people have in those around them [

48], personal well-being [

11], and consumers’ use and perceptions of information and communication technologies (ICT) [

49].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The set of data used in this study is freely made available by the European Social Survey (ESS) [

44]. This is a cross-national survey in its 10

th edition and covers 25 European countries. It was collected between the 25

th of May and the 18

th of September 2022. This survey has three aims:

“To monitor and interpret changing public attitudes and values within Europe and to investigate how they interact with Europe's changing institutions;

To advance and consolidate improved methods of cross-national survey measurement in Europe and beyond;

To develop a series of European social indicators, including attitudinal indicators. The survey involves strict random probability sampling, high response rate, and rigorous translation protocols.“

Data was collected through face-to-face interviews, however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic some interviews were performed via web or videoconference.

The survey covers several aspects of the European’s life, including social conditions and indicators, social behaviour and attitudes, general health and well-being, political behaviour and attitudes, political ideology, minorities, cultural and national identity, media, equality, inequality and social exclusion, language and linguistics, religion and values, family life and marriage [

45].

The represented universe in the sample includes persons aged 15 and over resident within private households, regardless of their nationality, citizenship, language or legal status, in the following countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Sweden, Slovenia, and Slovakia. The survey contains a total of 18.060 entries.

3.2. Variables included in the study

With the aim of studying consumerism in Europe, we have selected pertinent variables from the ESS. The surveyed individuals were asked several questions including a particular question of interest for our study and herein used as an independent variable: “Have you boycotted certain products in the last 12 months?”. The possible valid answers to the question were “yes” or “no”, the interviewees also had the choice of “no answer”, “refuse to answer” or “don’t know”.

As independent variables to explain the chosen dependent variable, we have selected questions related to demography, individual perception of the society and its policies, and exposure to internet and/or mobile communication systems. The variables that follow were used as independent variables.

Demographic: age, gender, marital status, years in education, and household size.

Individual perception of the society and its policies: trust in others, trust in the legal system, trust in scientists, satisfaction with the state of the economy, satisfaction with the government, satisfaction with the democratic system, happiness, satisfaction with the state of the education system, satisfaction with the state of the health services, and subjective general health.

We take the variables “trust in the legal system” and “trust in scientists” as proxies for institutional trust since law and science have been considered the two most relevant institutions directly or indirectly influencing policymaking [

46,

47].

The legal system serves as a framework for governance, providing a structured set of laws, regulations, and policies that can promote sustainable practices [

2,

3,

4]. It establishes guidelines for environmental protection, resource management, and social justice, creating a foundation for sustainable development. Additionally, the legal system can facilitate sustainable innovation and provide a platform for stakeholder engagement, driving collective efforts toward a sustainable future [

48]. Policymakers and citizens rely on sciences for accurate information on critical sustainability issues [

49]. Science trust is tied to the broader institutional contexts, in which scientists produce and disseminate knowledge [

49]. Research indicates that individuals tend to rely on pre-existing knowledge, values and beliefs as well as on their level of trust in science and scientific authorities to form attitudes towards sustainability issues [

50].

3.3. Statistical analysis

Due to the dichotomic nature of the dependent variable (yes, no) we have fitted models from the binomial family with a logit link to explain it. Firstly, we adjusted several models to access how each independent variable explains the dependent variable. Secondly, we entered all the variables in a multivariable model to produce a single model explained by the independent variables found significant. In the multivariable model, variables were selected after a backward stepwise procedure. Several link functions were also tested, and the best fit was chosen. The level of significance was set to p < 0.05.

The models were adjusted using the Generalized Linear Models routine in the statistical package IBM Corp.® SPSS® Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA. Version: 29.0.0.0 (241).

5. Discussion and conclusions

The main aim of this paper was to investigate institutional trust as a potential driver for consumers boycotting behaviour. Complementarily this research also aimed to empirically test other potential drivers for boycotts commonly mentioned in political consumerism literature. The model confirms the predictive power of several variables. Concerning the main focus of this research, the data indicates that past boycotting behaviour is positively affected by institutional trust. The single variable model indicates both a positive relationship between past boycotting behaviour and trust in the legal system and between past boycotting behaviour and trust in scientists.

The possible underlying mechanism for the positive relationship between boycotting behaviour and trust in the legal system is that consumers may be more willing to make individual sacrifices, such as abstention from consumption, if they believe that a higher authority has the capacity to observe their boycott behaviour and act accordingly [

6]. For example, pro-sustainability consumers may engage in boycotting to attract government attention and lead the government to act, by producing and implementing policy that forces companies to adopt sustainable business practices and to punish transgression. Trust in an institutional authority may lead political consumers to believe that their activism actions will have consequences and that their boycott initiatives will be reflected in government action. Furthermore, the results confirm that the probability of boycotting increases with trust in others. The dimensions of trust interact with each other. Sustainability as a long-term investment requires predictable conditions, so it is crucial that both social and institutional trust are established and exist at some level, for transition to take place [

37].

Social and institutional trust typically derive from previous experience, including perceptions concerning the competence of institutions [

51]. Our study confirms that past boycotting behaviour is positively affected by consumers’ satisfaction towards the government, the state of the democracy, the state of the health system and the state of the economy. This vision is coherent with the government´s role of trustee in sustainability, meaning a higher authority in charge with managing the affairs of another [

55], thus agency is a crucial tenet of institutional trust. Trust in public institutions implies an overall belief in institutional quality, or in this case, the government’s general capacity to manage and coordinate [

43].

Citizens, as well as policymakers, depend on science for accurate information on critical sustainability issues such as climate change. Our results indicate a positive relationship between boycotting behaviour and trust in science. Considering the gap in knowledge and information that separates scientists and consumers, trust in science, in its epistemic sense, may become a driver for sustainable behaviour [

54]. Furthermore, previous research indicates that citizens have a generally positive attitude toward the principle of scientists being involved in public policy and political debates [

49]. Science-informed policy is crucial in solving the interconnected and complex global to local sustainability problems society faces today. Equally important is the educational system, which plays a pivotal role in shaping sustainable mindsets, knowledge, and skills. The model indicates that the probability of boycotting increases as the years of full-time education increases. By integrating sustainability principles into curricula and educational practices, the educational system can equip individuals with the necessary tools to address sustainability challenges. It fosters awareness, critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities, empowering individuals to make informed decisions that contribute to sustainability. Moreover, the scientific and educational institutions themselves can serve as examples of sustainability by adopting eco-friendly practices, promoting sustainable behaviours among students and staff, and engaging with the wider community.

It was possible to confirm a gender gap in boycotting, since results indicate that females have a larger probability of engaging in such behaviour. This phenomenon has been attributed in classical consumerism literature to women’s role in household provisioning [

5,

52]. The data also confirms an age gap and the influence of life-cycle events in past boycott behaviour. Results indicate that the probability of boycotting decreases for older consumers and is lower in widows or if the civil partner has died, followed by legally separated, none of the stated or single and legally divorced or civil union dissolved, meaning that couples and families with higher number of members have the highest probability of engaging in boycotts.

In terms of the relationship between boycotting and personal well-being, the model indicates that the probability of boycotting increases with notions of self-happiness and decreases with positive self-health perceptions. Our exploratory analysis lends support to earlier research, which has shown that boycotts are not exclusively acts of altruism or ideological opposition [

53], individuals may oppose consumption based on self-interest, including the rejection of products that negatively affect their health. On the other side, some consumers may adopt anti-consumption driven primarily by objectives of happiness. In this case consumers reject the consumption of products that do not correspond to their ideal lifestyles and self-images [

12].

Although boycotting is usually framed under alternative forms of political participation [

17,

54], it was found that the probability of boycotting decreases with the time spent paying attention to politics and current affairs. These results suggest that consumers can engage in extreme forms of political consumerism, such as boycotting, without proper levels of knowledge and information about the issues involved. In opposition to the declining trend verified in traditional forms of political activity in Western democracies, such as voting and political party membership, this new century is characterized by the spread of alternative forms of political participation such as boycotts, a development that has been attributed to globalization and the widespread use of ICT, which have triggered a shared global sense of moral obligation [

7]. In fact, the model confirms the influence of digital communication in boycott behaviour. The probability of boycotting increases with the time spent on the internet. This finding is consistent with literature suggesting that ICT facilitates political consumption activities by allowing consumers to quickly disseminate information about boycott targets and persuade other consumers to participate [

14]. However, results also indicate that the probability of boycotting is positively affected by negative perceptions about ICT, including opinions that mobile communications and the internet makes work and personal life interrupt each other, expose people to misinformation and undermine consumers’ personal privacy. Social media have varied or even contradictory roles when it comes to shaping discussions around sustainability. Social media platforms are important sources of information for consumers to learn about boycott initiatives and for activist movements to organize [

19]. However, some of these digital platforms are also becoming the target of boycotts. For example, Facebook has suffered several boycotts due to misinformation on its platform as well as the way it handles contentious political issues [

55]. Conspiracy theories and disinformation spread rapidly and are amplified through social media [

2]. Negative perceptions about ICT may lead consumers to question the veracity on information available in the digital world and became more reluctant to engage in pro-sustainability consumerism.

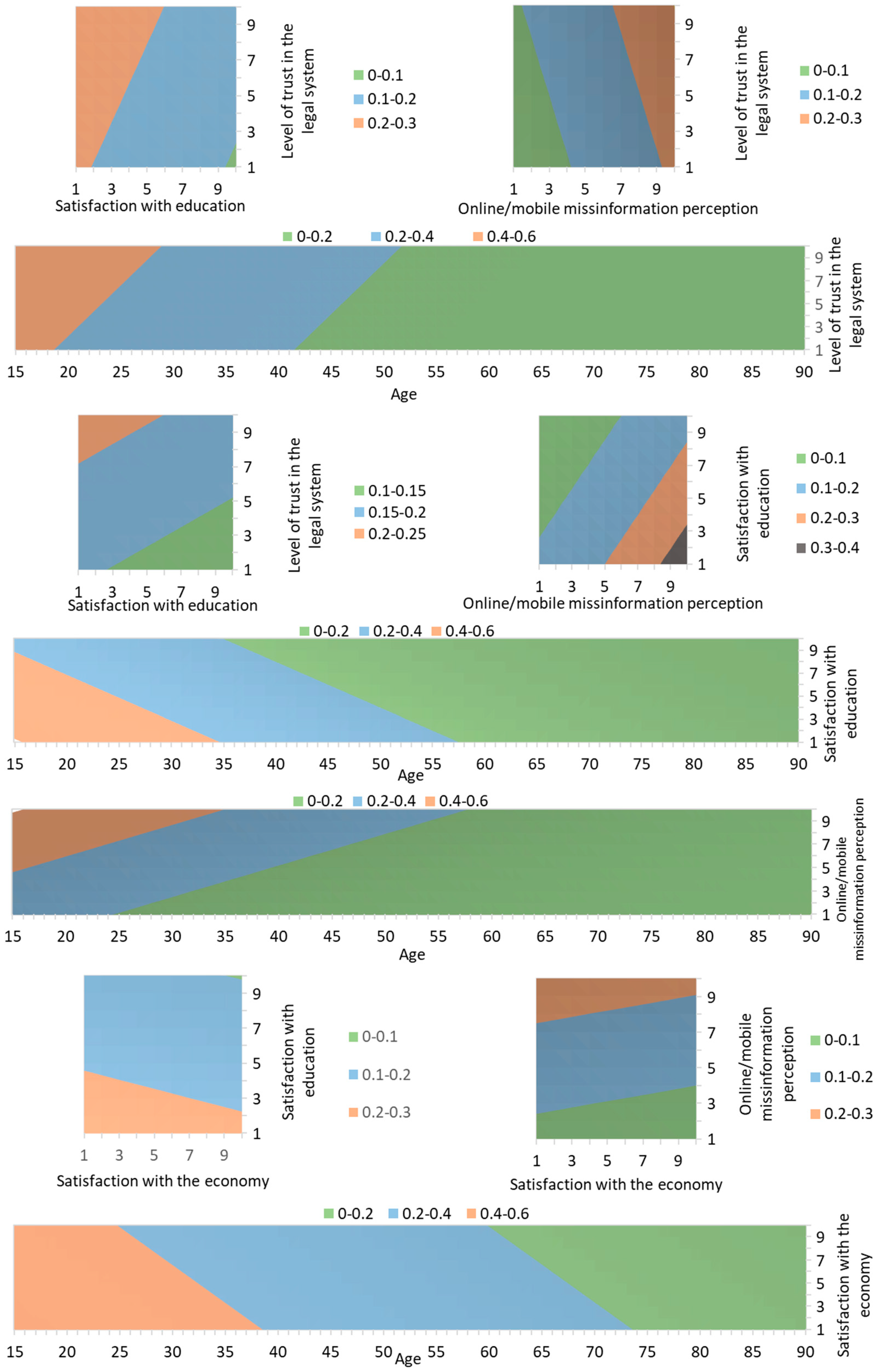

Finally, based on the interpretations of the multivariate model (please, see graphs in

Figure 1) it was possible to conclude that the probability of having boycotted a certain product in the past two years:

Is lower in individuals more satisfied with the status of the education in their countries and lower levels of trust in the legal system of their countries;

Is lower in individuals with both, lower levels of perception of misinformation in online/mobile communications, and lower levels of satisfaction in the legal system of their countries;

Is lower in older individuals with higher levels of trust in the legal systems of their countries;

Is lower in individuals with higher levels of satisfaction with the state of education in their countries and lower levels of trust in the legal system of their countries;

Is lower in individuals with lower perception of online/mobile misinformation and higher levels of satisfaction with the state of education in their countries;

Is lower in older individuals with higher levels of satisfaction with the state of education in their countries;

Is lower in older individuals with lower levels of perception of online/mobile misinformation;

Is lower in individuals with higher degrees of satisfaction with both the state of the economy and the state of the education in their countries;

Is lower in individuals with higher levels of satisfaction with the state of the economy of their countries and lower levels of perception of online/mobile misinformation;

Is lower in older individuals with a higher degree of satisfaction with the state of the economy in their countries.

These results suggest that the interplay between drivers of product boycott is complex and deserves further analysis. For example, age seems to play a decisive and complex role in boycotting decisions. While the univariate analysis indicates that boycott is generally positively influenced by trust in the legal system, older individuals have a lower probability of engaging in boycotting when the level of trust in the legal systems of their countries increases. Also, the probability of boycotting is lower in older consumers with reduced levels of perception of online/mobile misinformation. In addition, the multivariate analysis also indicates that the probability of having boycotted a certain product in the past two years is lower for individuals with both, lower levels of perception of misinformation in online/mobile communications, and lower levels of satisfaction in the legal system of their countries. These results indicate that the drivers for product boycott are characterized by multidimensionality, complex processes, and consumers with different motivations. This same conclusion was reached by previous research. For example, Baptista and Rodrigues recurred to a clustering methodology to produce a segmentation model of boycotters that offered a two clusters solution and concluded that the two segments, labelled conservative majority and active idealists, revealed significant differences in their levels of institutional trust [

7].

Recognizing the importance of institutional trust for implementing sustainability Weymouth and colleagues [

43] suggest several measures to increase institutional trust, including the government use of deliberative communication modes with consumers, involving the public exchange of reasons between people representing different perspectives on sustainability issues; the distribution of power combined with collaborative action between stakeholders, since centralized decision making can be too slow or too unnuanced to effectively address the inherent challenges; and the importance of adopting a scientific, evidenced-based perspective when mapping the problems and searching for solutions. In our view, other possible routes to improve institutional trust involve institutional and social innovation. Institutional innovation may involve partnerships linking consumers’ organizations and government agencies and collaborative ventures for sustainability. Considering the difficulties faced by governments in addressing some sustainability issues, policy intervention can focus in supporting third sector social enterprises and public-private partnerships, involving society and private sectors, which can bring both desirable effectiveness and efficiency to scalable pro-sustainability social innovation [

48].

Despite the importance of the institutional dimension at the interface of the other dimensions of sustainability (environmental, social and economic), there remains a paucity of research focused on this topic. The findings of this research have significant implications for policymakers, educators, and stakeholders involved in sustainability initiatives. Understanding the role of institutional trust in driving pro-sustainability behaviour can inform the design of policies, regulations, and educational programs that foster sustainable practices. Next, we enumerate some relevant research opportunities. First there is the need of conceptual studies that further explore the complex relationship exhibited in this study between institutional trust and consumers’ pro-sustainability behaviour. While findings here suggest a link between institutional trust and boycotting behaviour at a general global level, further analyses of this relationship are needed, focusing on specific sustainability issues. Second, our attempt to identify drivers of product boycott does not reveal much about the nature and interdependencies of these drivers. So, empirical studies are needed to understand how drivers relate. Third, research can adopt a case-study approach and focus on understanding the extent to which consumers’ boycotts are effective in tackling some specific sustainability challenges, such as climate change, poverty, income inequality or gender discrimination. Finally, despite the contributions made, this study has some limitations. The selection of variables was supported on political consumerism literature; however, it is possible that some relevant explanatory variables are missing from the study and causality relationships cannot be proven.