1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is currently the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in Poland [

1,

2]. Each year, over seventeen thousand new cases are reported in Poland, with more than 5.7 thousand resulting in death [

2]. Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men, following lung cancer. This cancer exhibits the highest growth rate in incidence. Over the past three decades, the number of cases has increased approximately fivefold.

The most significant risk factors for developing prostate cancer include age, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors such as a diet rich in animal fats and exposure to heavy metals [

3,

4]. The risk of developing this cancer increases with age and sharply rises after the age of 60, reaching its peak after the age of 75 [

5].

In the early stages, this cancer often remains asymptomatic [

5]. Symptoms that may occur as the disease progresses are related to the genitourinary system. Patients may experience difficulties with urination, nycturia, frequent urination, increased urgency to urinate, urinary tract infections, and sexual dysfunctions in the form of erectile dysfunction [

6]. The nature of these symptoms can be distressing for patients, contributing to worsened mental state, development of depression, and significantly reduced quality of life. There are many effective treatment methods for prostate cancer, which depend mainly on the stage of the tumour, age, and comorbidities. Radical prostatectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with localized cancer and a predicted life expectancy of over 10 years, while hormonal therapy is used in advanced stages [

7,

8]. Radiation therapy is often used as an adjunctive treatment. It can be applied as an adjuvant to surgical treatment in cases of localized cancers or palliatively in advanced cases. The most commonly used methods are HDR (High Dose Rate) brachytherapy and permanent seed brachytherapy [9-11]. Brachytherapy provides precise treatment and the high radiation dose reduces the treatment time.

With the increasing detection of prostate cancer, resulting from the growing awareness of the disease and the widespread testing of PSA levels, patients have an increased chance of survival and maintaining their current quality of life. The evaluation of quality of life plays a crucial role in the assessment and treatment of cancer patients.

This study aims to assess the quality of life of patients after prostate brachytherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the Lower Silesian Oncology Centre in Wroclaw, Poland, in the Inpatient Radiotherapy Department from November 2020 to March 2021. Written consent was obtained from the Directorate and the Head of the Department, as well as from the Bioethics Committee No. KB – 794/2020. The survey involved fifty respondents aged 51 to 85 years. Each participant gave informed and voluntary consent to participate in the survey. The inclusion criteria for the survey were a diagnosis of prostate cancer and treatment with brachytherapy. The surveys included standardized questionnaires: EORTC QLQ C-30, QLQ PR-25 (in the Polish version), PSS-10, Mini-MAC Scale, KATZ Scale, and a self-developed socio-demographic particulars.

The EORTC QLQ C30 questionnaire includes five scales assessing functional status, which are related to physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning. It also includes three scales assessing symptoms: fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain. In addition, it includes six single-item questions assessing symptoms such as loss of appetite, dyspnea, insomnia, constipation, diarrhoea, and financial difficulties as a consequence of the disease. This is a descriptive questionnaire to be completed by cancer patients. It consists of 30 Likert scale questions (28 questions on a 4-point scale and 2 questions on a 7-point scale). The questions are transformed into scales ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores in the functional scales and quality of life scales indicate better functioning or quality of life, while higher scores in the symptom scales indicate higher symptom severity . The reliability of the tool in the conducted study was 0.95, and the average item correlation was r=0.43 [

12,

13].

The QLQ-PR25 questionnaire is intended for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer. It assesses the quality of life related to physical, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning. The QLQ-PR25 consists of 25 questions on a 4-point scale, where 1 indicates “not at all,” 2 indicates “somewhat,” 3 indicates “considerably” and 4 indicates “very much so”. The reliability of the tool in the conducted study was 0.89, and the average item correlation was r=0.28 [

14,

15].

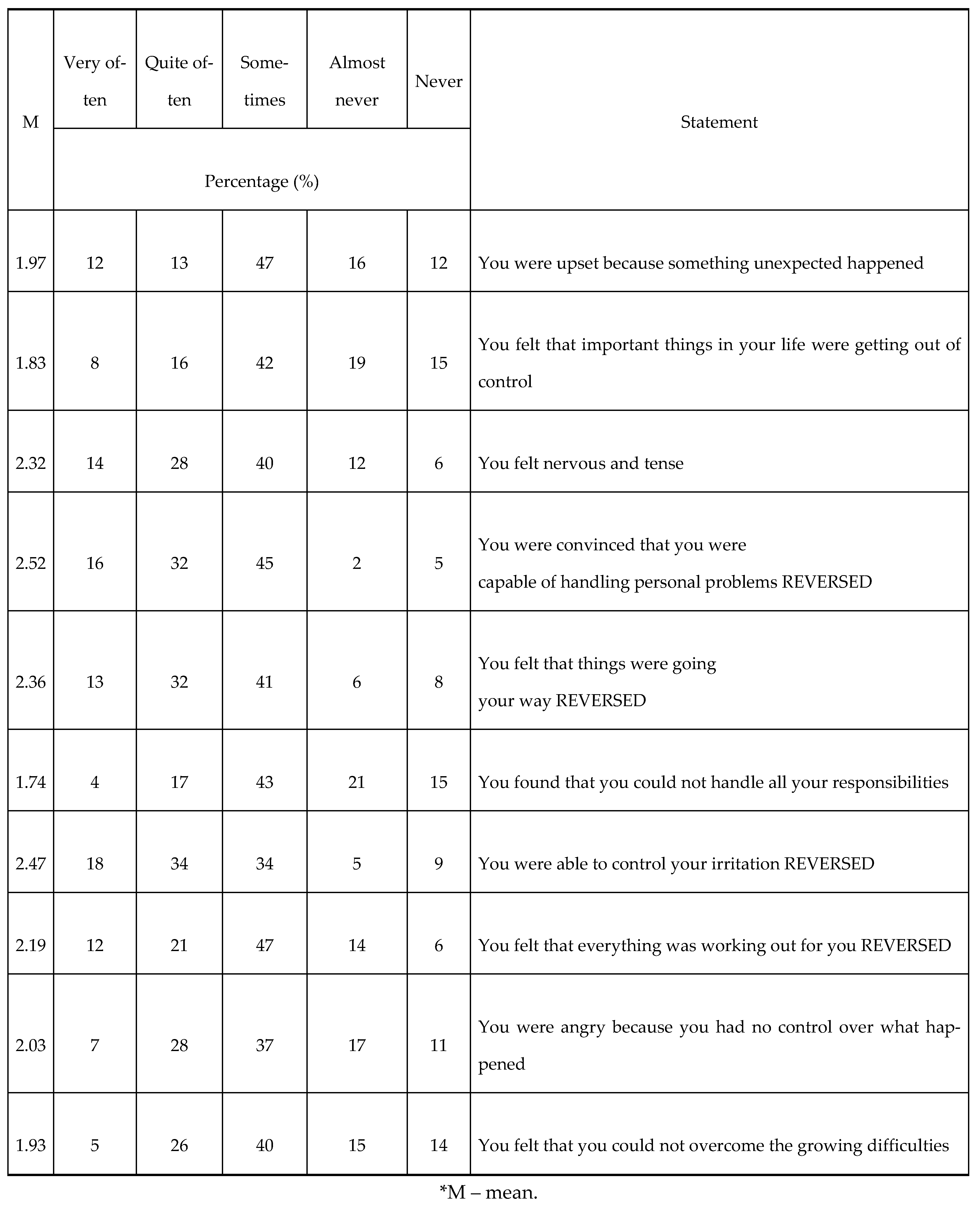

The PSS-10 (Perceived Stress Scale-10) assesses the degree of perceived stress. It is used for evaluation of the level of stress associated with one’s own life situation over the past month. It consists of 10 questions on a 1-4-point scale, addressing various subjective feelings related to problems, personal events, behaviour, and coping strategies. The PSS-10 can be used for the identification of individuals in need of psychotherapeutic and medical assistance. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress. The reliability of the tool in the conducted study was 0.83, and the average item correlation was r=0.33 [

16].

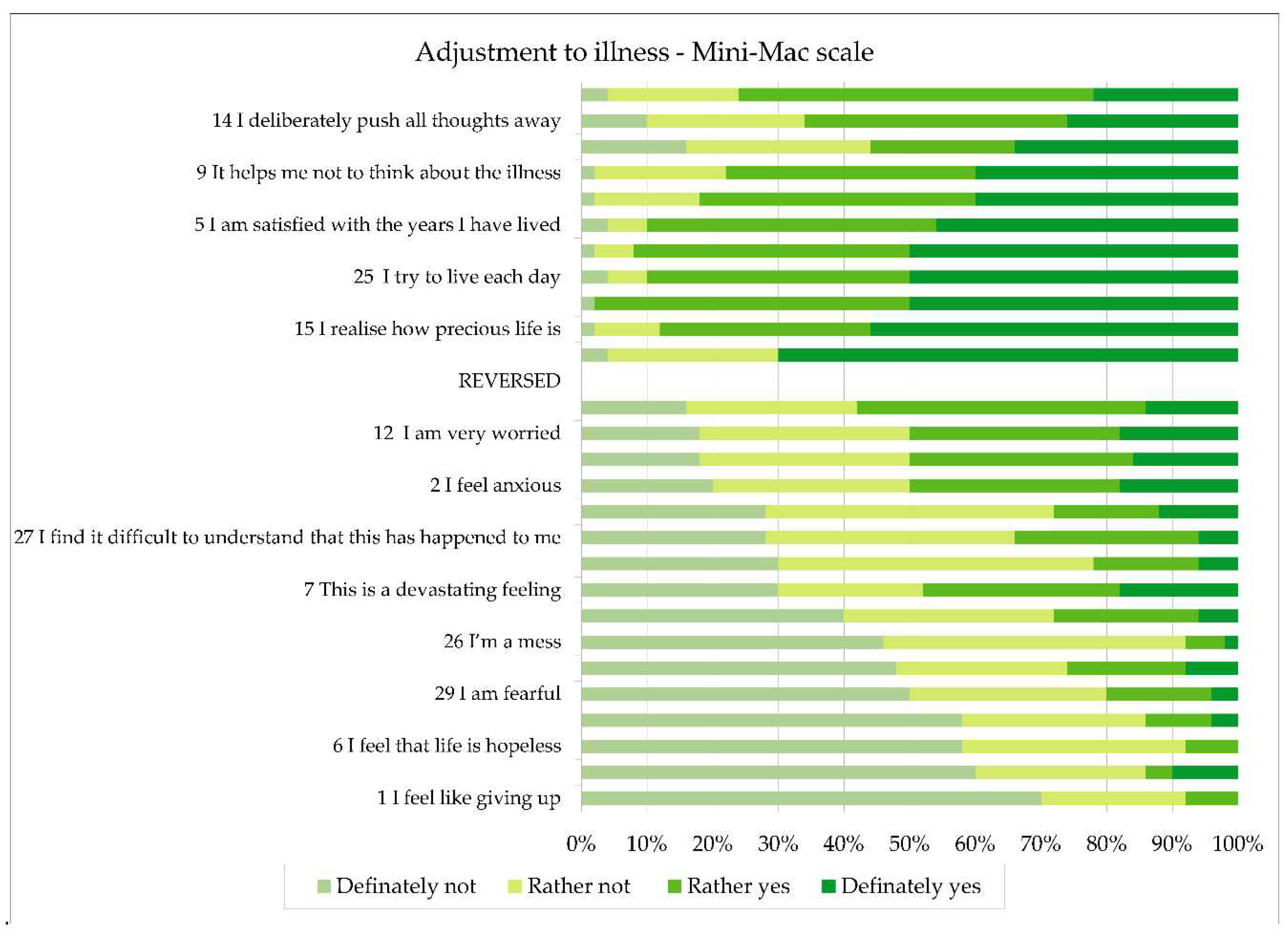

The Mini-MAC (Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer) contains 29 statements to which the respondent expresses agreement or disagreement on a 4-point scale (definitely not, rather not, rather yes, definitely yes). The Mini-MAC scale measures four coping strategies: anxious preoccupation, fighting spirit, helplessness-hopelessness, and positive redefinition. The reliability of the tool in the conducted study was 0.89, and the average item correlation was r=0.22 [

17,

18].

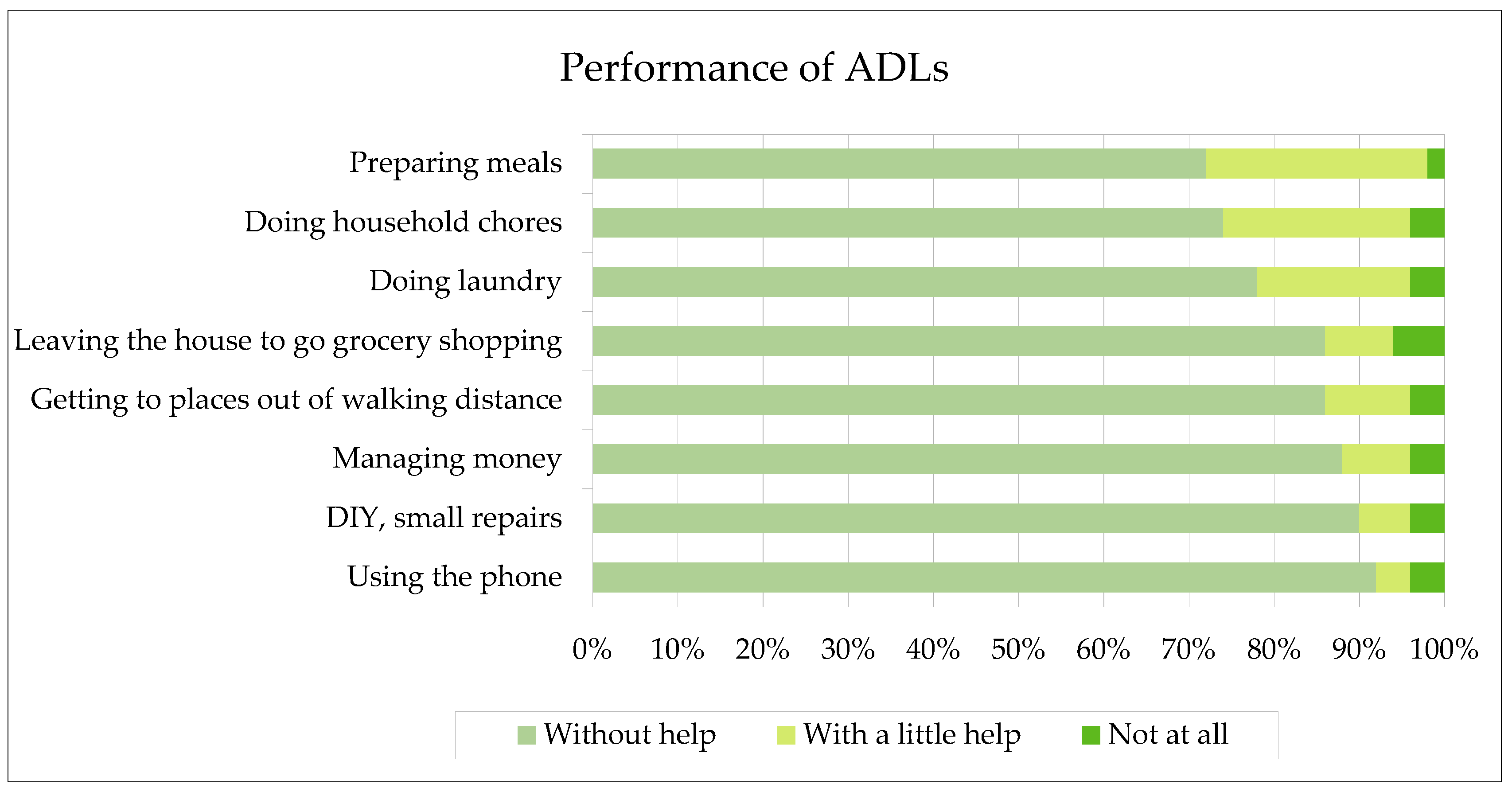

The ADL-Katz scale assesses the patient’s independence in 6 activities of daily living (ADLs): ability to maintain hygiene; ability to dress and undress independently; basic mobility; control of basic physiological functions, which are answered with a “yes” or “no” response. For each ADL performed independently, 1 point is awarded. Obtaining 5-6 points indicates that the respondent is independent, while obtaining 2 or fewer points indicates significant disability [

19].

The IADL scale is used form assessment of instrumental ADLs. It consists of 9 questions, where scores range from 1 to 3 points for each question. Three points indicate independent performance of a given activity. Two points indicate minor assistance, and one point indicates complete dependency of the respondent. A maximum score (27 points) indicates complete independence, a score of 10 to 26 points indicates partial dependency and moderate assistance, while a score of 1-9 points indicates severe dependency and low level of independence. The reliability of both the ADL and IADL instruments was 0.93, and the average position correlation was r = 0.55 [

20].

The self-designed questionnaire contains 8 questions related to the patient’s socio-demographic data. The questions include the patient’s age participating in the study, place of residence, marital status, level of education, employment status, assessment of economic situation, frequency of physical activity, and time elapsed since diagnosis.

The following tools were used for the analysis: Mann-Whitney U test to check the equality of means between two unequal independent groups, Student’s t-test to check the equality of means between two equal independent groups, correlation coefficients – Kendall’s tau (τ) and Spearman’s correlation (r), as well as the chi-squared test (χ²) (according to the data characteristics – nominal, ordinal, interval, and categorical numbers). The interpretation of the strength of the correlation calculated using the Spearman correlation coefficient (r) utilized the Guilford scale. The threshold value was set at p < 0.05, and when p fell within the range of <0.05-0.1>, it was considered a statistical tendency. The reliability of the scales used in the study was assessed by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each tool. The analysis was conducted using PQ Stat 18.0 software.

3. Results

The study group consisted of fifty men aged between 51 and 85 years old, with a mean age of 67 years. Based on a self-designed questionnaire assessing socio-demographic data, it was observed that 40% of the respondents permanently resided in cities with over 100,000 inhabitants, 20% lived in the smallest towns, 28% lived in rural areas, and the remaining respondents lived in cities with populations ranging from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants. Among the respondents, the dominant group was individuals with vocational education, accounting for 38% of the participants, followed by 36% with secondary education and 22% with higher education. In the studied population, 32% were actively employed, 62% were retired, and 6% were on disability pension. Among the male participants, 44% declared their financial situation to be at a good level, while 20% declared their material status as very good, allowing them to afford larger, unplanned expenses. However, 36% of individuals reported that their income was sufficient for daily needs but they had to save for larger expenses. In terms of physical activity, 30% of respondents stated that they were physically active several times a week, 24% reported daily physical activity, and another 24% declared being active 1-2 times a week. However, 22% of participants were physically active less than once a week. Among the men surveyed, 40% were not sexually active. Within the group of sexually active men, 2% reported high sexual activity, 26% reported significant activity, and 32% reported moderate sexual activity. The majority of patients were diagnosed with prostate cancer within a year (72%), while 22% of men received a diagnosis within 1-3 years, 4% were diagnosed within 2-5 years, and 2% were diagnosed after more than 10 years.

The PSS10 was used for the assessment of the psychological state of the patients. The minimum score obtained in this scale was 11 points, while the maximum score was 29 points. The results are shown in

Table 1.

Using the Mini-MAC scale, the patient’s adjustment to illness was assessed. There was a significant variation in results, with a minimum score of 35 points and a maximum score of 89 points. The average score in the sample was 55 points, with a standard deviation of SD=12.2. The results are shown in

Figure 1.

In terms of basic activities of daily living, as assessed based on the (ADL)-KATZ scale, the average score was 20 points while a minimum score was 11 points and a maximum score – 29 points. The percentage results are shown in

Figure 2.

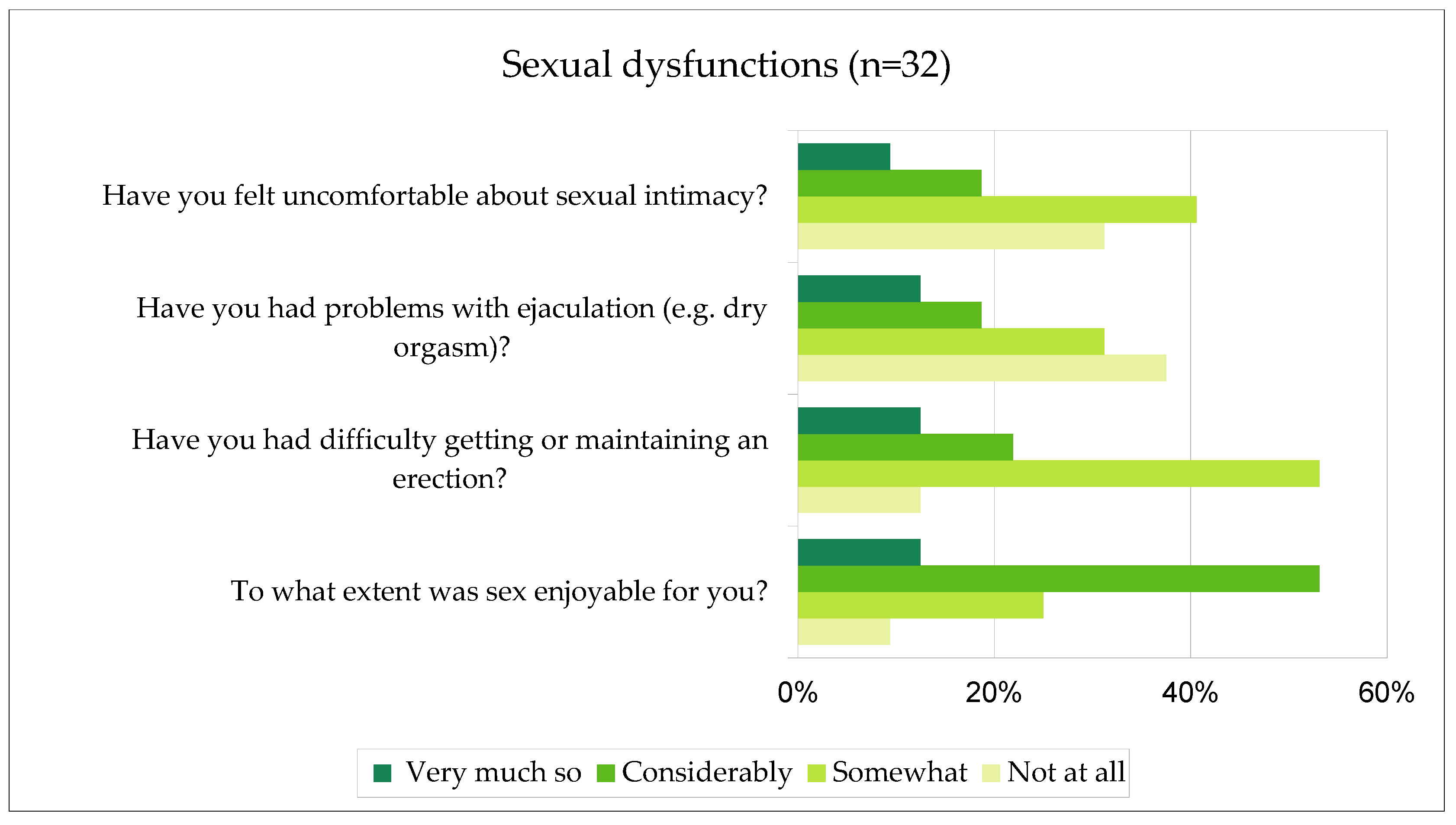

Individuals who reported being sexually active were additionally asked about the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions after brachytherapy. The type and intensity of these dysfunctions were determined. The percentage results are shown in

Figure 3. Those dysfunctions were not present before the use of brachytherapy. The study revealed that brachytherapy has an impact on the degree of sexual dysfunctions among sexually active patients.

Patients’ quality of life (QoL) in the past week was assessed based on question 29 of the QLQ30 scale using a 7-point scale, where 1 indicates very poor QoL and 7 indicates excellent QoL. The results show that 12 patients rated their QoL as excellent, 18 as very good, 30 as good, 24 as moderate, and 16 as poor.The relationship between the stage of the disease and the level of QoL was examined by using the Spearman correlation coefficient. The disease stage was assessed based on the QLQ25 scale, while the QoL was measured using the QLQ30 scale. The coefficient was found to be r=-0.52, p<0.01. It was concluded that there is a statistically significant correlation between those two variables with strong relationship between them (according to Guilford’s classification).

Based on the responses to the QLQ30 scale questions, patients were assigned to two groups: low QoL and high QoL. It was found that belonging to those groups does not have a statistically significant impact on the performance of basic ADLs according to the KATZ scale. However, the group of patients with low QoL had more difficulty performing instrumental ADLs (IADLs) compared to the group with high QoL (p<0.05). The results are shown in

Table 2.

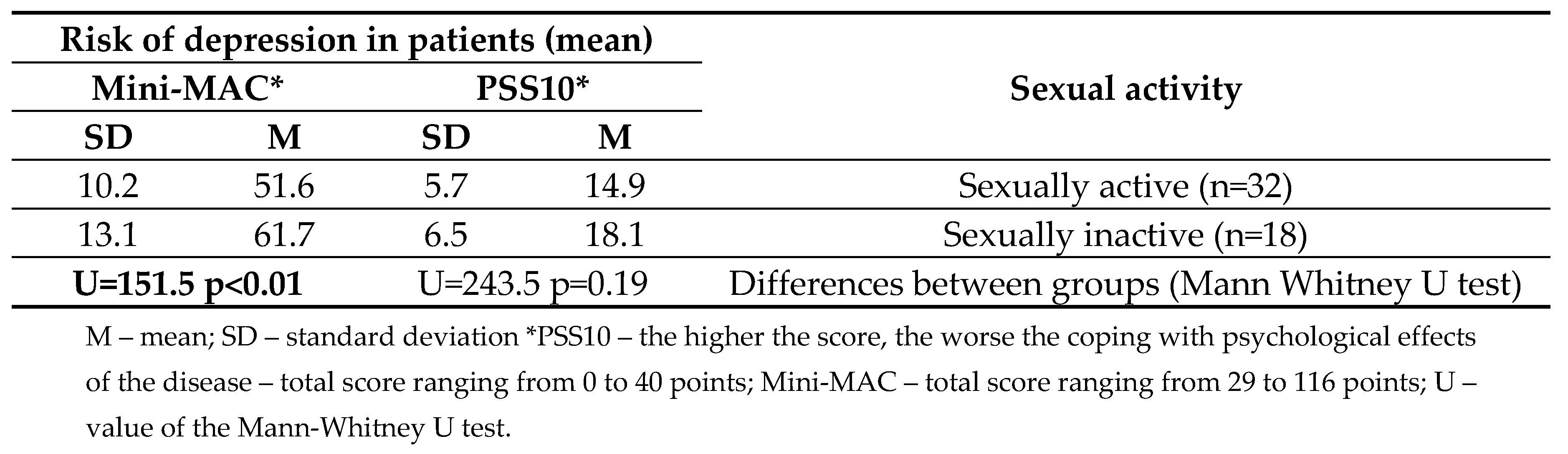

There was a statistically significant correlation between the level of sexual activity and the risk of depression. Sexually inactive individuals more frequently experience negative psychological symptoms, resulting in an increased risk of depressive disorders in this patient group. Statistical significance was only demonstrated based on the assessment using the Mini-MAC scale (p<0.01), while no statistical significance was found based on the assessment using the PSS10 scale (p=0.19). The analysis revealed a moderate correlation according to Guilford’s classification, in which an increase in negative psychological symptoms is accompanied by a decrease in interest in sex. The analysis also concluded that the intensity of sexual dysfunctions and the level of stress in patients diagnosed with prostate cancer mutually influence each other. The results are shown in

Table 3.

The analysis revealed significant correlations (at p<0.01) between disease symptoms and depression. There was an extremely high positive correlation (according to Guilford’s classification) between QoL measured by the QLQ-C30 scale and depression – the more disease symptoms, the greater the risk of depression.

There was a relationship between the influence of independence level, choice of coping strategies, economic status, physical activity, and the level of quality of life (p<0.01). Low level of independence, lack of coping with stress, and low economic status negatively affect the quality of life. Higher frequency of physical activity positively influences the quality of life and is a positive predictor of its improvement.

4. Discussion

The assessment of patients’ quality of life is an extremely important issue in medicine, and its value has been increasing in recent years. Special attention is given to oncology patients. Quality of life is assessed in a multidimensional way, considering emotional, psychological, social, physical, and spiritual aspects.

As patients develop cancer, there is severe stress associated with the burden of symptoms, fear of the disease, fear of poor prognosis, and usually the prospect of long-term treatment, which significantly impacts the quality of life [

21]. Due to the diagnosis of prostate cancer, there is a context of the impact of the disease on interest in sex and sexual activity. The type of treatment used can also influence the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions. In the presented study, it was found that brachytherapy significantly contributed to the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions. The chosen treatment method impaired achieving or maintaining an erection, made ejaculation difficult, and had a negative impact on the emotional approach to the topic of sex – patients felt uncomfortable, lost interest in sexual activities, and found sexual activity less enjoyable than before.

In their study, Roeloffzen et al. revealed that patients treated with brachytherapy for prostate cancer developed urinary, and gastrointestinal complaints. The treatment also increased pain and impaired physical performance and sexual activity [

22]. Similarly, a study by Brandeis et al. found that patients after brachytherapy were more likely to experience symptoms related to urinary tract irritation, and it also negatively affected the sexual function of those patients. Although the overall quality of life did not worsen in that group of men, the level of health-related quality of life was reduced by the occurrence of bothersome symptoms related to the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems [

23]. Sexual dysfunctions affect a very intimate sphere of patients, making it emotionally challenging for them and affecting their mental state. This can make it difficult for these patients to openly discuss such radiation therapy-related side effects with their doctors. According to the study by Merrick et al., erectile dysfunction occurs in up to 50% of patients undergoing brachytherapy for prostate cancer. These disorders are most commonly reported within the first 5 years following treatment. However, Merrick et al. note that despite the occurrence of erectile dysfunction in this group of men, they respond well to the use of sildenafil, which improves their sexual life [

24,

25]. Many other studies published in the available literature have also observed increased urinary urgency, urinary incontinence, frequent urination, and sexual dysfunctions in men during or immediately after brachytherapy [26-28]. Factors such as the patient’s age and his baseline sexual quality and activity also influence the quality of his sexual life [

29]. Despite the worsening of sexual function and urinary incontinence issues, the overall quality of life of these patients is satisfactory [

30].

The choice of coping strategies for cancer and stress have a greater impact on quality of life [

31]. Patients experience high levels of stress and uncertainty about the future from the moment of diagnosis. According to an article published by Groarke et al., stress was found to be the greatest predictor of deterioration in quality of life and severity of mental disorders in patients [

32]. The sense of uncertainty and anxiety promotes destructive coping methods, which in turn negatively affect quality of life [

33]. The presence of sexual dysfunctions also affects the mental state and may contribute to an increased risk of depression. Hartmann’s publication encourages routine screening to assess the risk of depression in every patient with sexual dysfunctions and emphasises that improvement in sexual function is an extremely important predictor of depression remission [

34]. It is also worth noting that there is a strong bidirectional influence between sexual dysfunctions and depression. The occurrence of sexual dysfunctions increases the risk of depression, and vice versa [

35]. Poor coping with cancer also exacerbates the intensity and frequency of symptoms. This can lead to an impairment of patients’ independence and a worsening ability to perform IADLs. Among factors unrelated to the disease, older age, low education level, and low financial status are negative predictors of quality of life [

36]. All of these factors worsen quality of life. However, there are studies suggesting the significant importance of physical activity, which can contribute to reducing the side effects of treatment and improving quality of life [

37,

38]. This is a hypothesis supported by the results of our study. Physical activity following local radiotherapy for prostate cancer reduces fatigue, improves cardiac fitness, and physical and social well-being, thereby positively impacting overall quality of life [

39].

Despite the negative impact of brachytherapy on the genitourinary system, which can potentially lower the quality of life for patients, it is not the sole determinant of quality of life. Overall quality of life is influenced to a greater extent by factors such as disease stage, mental state, physical activity, and financial situation.

This study aims to draw attention to the significance of the impact of prostate brachytherapy on patients’ lives. Awareness of the effects of this treatment method on sexual function and quality of life should be highly important for clinicians. It is suggested that oncologists engage in conversations with patients about these matters and build trust in the doctor-patient relationship. It is important that when sexual dysfunctions occur, the patient has the courage to share the problem, and the clinician knows how to help and treat the patient. It is crucial to consider the intimate nature of these dysfunctions and their impact on patients’ mental health. Therefore, we encourage clinicians with prostate cancer patients under their care not to hesitate to seek help from psychologists or psychiatrists when treatment has a negative impact on mental status. A holistic approach to patients and the assessment of quality of life should be a standard in medical care.

4.1. Limitations

A potential limitation of this study is the small number of patients, therefore the results of this study should be treated with caution. We encourage future researchers to raise up a subject in long-term research on a larger group of patients.

5. Conclusions

Prostate brachytherapy exacerbates the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions, which contributes to a reduction in quality of life.

Individuals who are sexually active exhibit fewer negative psychological symptoms compared to those who are sexually inactive.

There is a correlation between quality of life and disease stage, coping strategies for stress, level of independence in performing activities of daily living, economic status, and level of physical activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.; methodology, A.T.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, E.M. and A.T..; resources, A.T and W.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, W.M.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee No. KB – 794/2020 for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wardecki, D.; Dołowy, M. Prostate cancer- current therapeutic possibilities. Polish title: Rak prostaty – aktualne możliwości terapeutyczne. Farm Pol 2022, 78, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkologia.org.pl. Available online: https://onkologia.org.pl/pl/raporty (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Gandaglia, G.; Leni, R.; Bray, F.; Fleshner, N.; Freedland, S. J.; Kibel, A.; La Vecchia, C. Epidemiology and prevention of prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gann, P. H. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Rev. in Urol. 2002, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J. Oncol., 2019, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriel, S. W.; Funston, G.; Hamilton, W. Prostate cancer in primary care. Adv Ther 2018, 35, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, M.; Crook, J.; Morton, G.; Vigneault, E.; Usmani, N.; Morris, W. J. Treatment options for localized prostate cancer. Can Fam Physician 2013, 59, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Achard, V; Putora, P. M.; Omlin, A., Zilli, T., Eds.; Fischer, S. Metastatic prostate cancer: treatment options. Oncol, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis, G.; Kelekis, N.; Armonis, V.; Kouloulias, V. Brachytherapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review. Adv Urol 2009. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, L. C.; Morton, G. C. High dose-rate brachytherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, J.; Marbán, M.; Batchelar, D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 30, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, N.; Fayers, P.; Aaronson, N.; Bottomley, A.; de Graeff, A.; Groenvold, M.; Sprangers, M. A. G. EORTC QLQ-C30. Reference values. Brussels: EORTC. 2008.

- Fayers, P.; Bottomley, A. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Quality of life research within the EORTC—the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur. J. Cancer 2002, 38, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, G.; Bottomley, A.; Fosså, S. D.; Efficace, F.; Coens, C.; Guerif, S.; Aaronson, N. K. An international field study of the EORTC QLQ-PR25: a questionnaire for assessing the health-related quality of life of patients with prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.; Popovic, M.; Chow, E.; Cella, D.; Beaumont, J. L.; Lam, H.; Bottomley, A. Development, characteristics and validity of the EORTC QLQ-PR25 and the FACT-P for assessment of quality of life in prostate cancer patients. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2014, 3, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M. G.; Ørnbøl, E.; Vestergaard, M.; Bech, P.; Larsen, F. B.; Lasgaard, M.; Christensen, K. S. The construct validity of the Perceived Stress Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 84, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerw, A. I.; Marek, E.; Deptała, A. Use of the mini-MAC scale in the evaluation of mental adjustment to cancer. Contemp. Oncol. 2015, 19, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, M.; Law, M. G.; Santos, M. D.; Greer, S.; Baruch, J.; Bliss, J. The Mini-MAC: further development of the mental adjustment to cancer scale. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1994, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, I. A comparative review of the Katz ADL and the Barthel Index in assessing the activities of daily living of older people. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2007, 2, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale. Medsurg Nurs 2009, 18, 315–316. [Google Scholar]

- Radecka, B. Quality of life conditioned by health - meaning and methods of assessment in cancer patients. Polish title: Jakość życia warunkowana zdrowiem – znaczenie i sposoby oceny u chorych na nowotwory. Curr Gynecol Oncol. 2015, 13, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeloffzen, E. M.; Lips, I. M.; van Gellekom, M. P.; van Roermund, J.; Frank, S. J.; Battermann, J. J.; van Vulpen, M. Health-related quality of life up to six years after 125I brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandeis, J. M.; Litwin, M. S.; Burison, C. M.; Reiter, R. E. Quality of life outcomes after brachytherapy for early stage prostate cancer. J.Urol. 2000, 163, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, G. S.; Wallner, K. E.; Butler, W. M. Management of sexual dysfunction after prostate brachytherapy. Oncol. (Williston Park, NY) 2003, 17, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Potters, L.; Torre, T.; Fearn, P. A.; Leibel, S. A.; Kattan, M.W. Potency after permanent prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001, 50, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, C.; Schoffelmeer, C. C.; Tillier, C.; de Blok, W.; van Muilekom, E.; van der Poel, H. G. Quality of life in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. A comparative retrospective study: brachytherapy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus active surveillance. J.Endourol. 2014, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houede, N.; Rebillard, X.; Bouvet, S.; Kabani, S.; Fabbro-Peray, P.; Trétarre, B.; Ménégaux, F. Impact on quality of life 3 years after diagnosis of prostate cancer less than 75 years of age at diagnosis: observational case-control study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbal, C.; Tinay, I.; Şimşek, F.; Turkeri, L. N. Erectile dysfunction following radiotherapy and brachytherapy for prostate cancer: pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2008, 40, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Asakawa, I.; Anai, S.; Miyake, M.; Hori, S.; Fujimoto, K. Quality of life in patients who underwent 125I brachytherapy, 125I brachytherapy combined with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy, or intensity-modulated radiation therapy, for prostate cancer. J. Radiat. Res. 2019, 60, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buergy, D.; Schneiberg, V.; Schaefer, J.; Welzel, G.; Trojan, L.; Bolenz, C.; Wenz, F. Quality of life after low-dose rate brachytherapy for prostate carcinoma – long-term results and literature review on QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 results in published brachytherapy series. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. W.; Barden, S.; Terk, M.; Cesaretti, J. The influence of stigma on the quality of life for prostate cancer survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 35, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, A.M.; Curtis, R.; Skelton, J.; Groarke, J.M. Quality of life and adjustment in men with prostate cancer: the interplay of stress, danger and resilience. PloS One 2020, 15, e0239469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Santacrocoe, S.J.; Chen, D.G.; Song, L. Illness uncertainty, coping, and quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncol. 2020, 29, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, U. Depression and sexual dysfunction. J Mens Health 2007, 4, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlantis, E.; Sullivan, T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2012, 9, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, S. K.; Ng, S. K.; Baade, P.; Aitken, J. F.; Hyde, M. K.; Wittert, G.; Dunn, J. Trajectories of quality of life, life satisfaction, and psychological adjustment after prostate cancer. Psychooncol. 2017, 26, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendeiro, J. A.; Rodrigues, C. A. M. P.; de Barros Rocha, L.; Rocha, R. S. B.; da Silva, M. L.; da Costa Cunha, K. Physical exercise and quality of life in patients with prostate cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4911–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.; Hayes, S.C.; Newman, B. Level of physical activity and characteristics associated with change fallowing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psychooncol. 2009, 18, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, U.; Garber, S. L.; Thornby, J.; Vallbona, C.; Kerrigan, A. J.; Monga, T. N.; Zimmermann, K. P. Exercise prevents fatigue and improves quality of life in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007, 88, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).