Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proposed intervention program for CPTSD

2.2. Subject

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative analysis

2.3.2. Qualitative analysis

3. Results

3.1. Therapeutic intervention and symptom change during proposed program

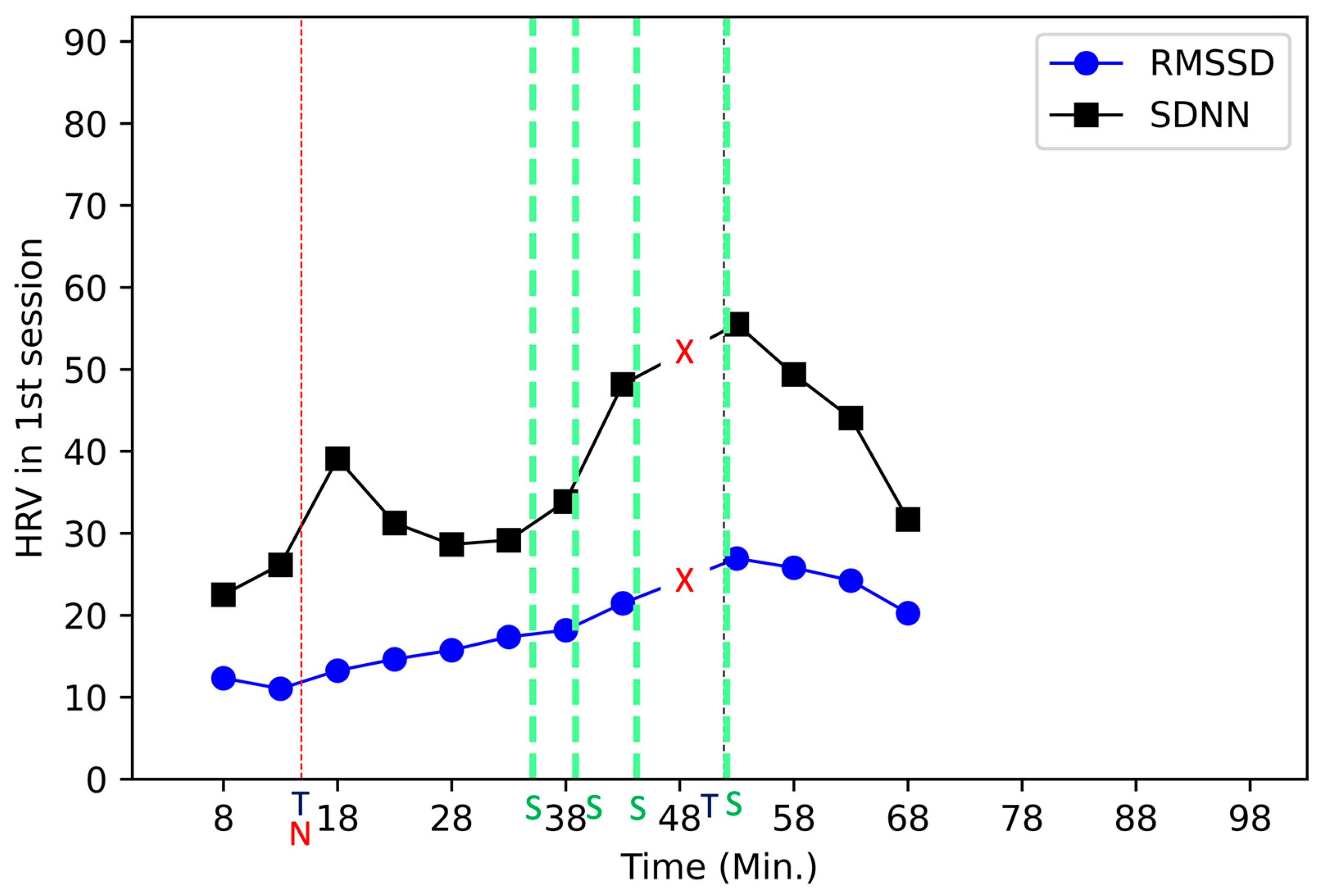

3.1.1. Session one: Exploring traumatic event and CPTSD symptoms, creating safety zone and training stabilization

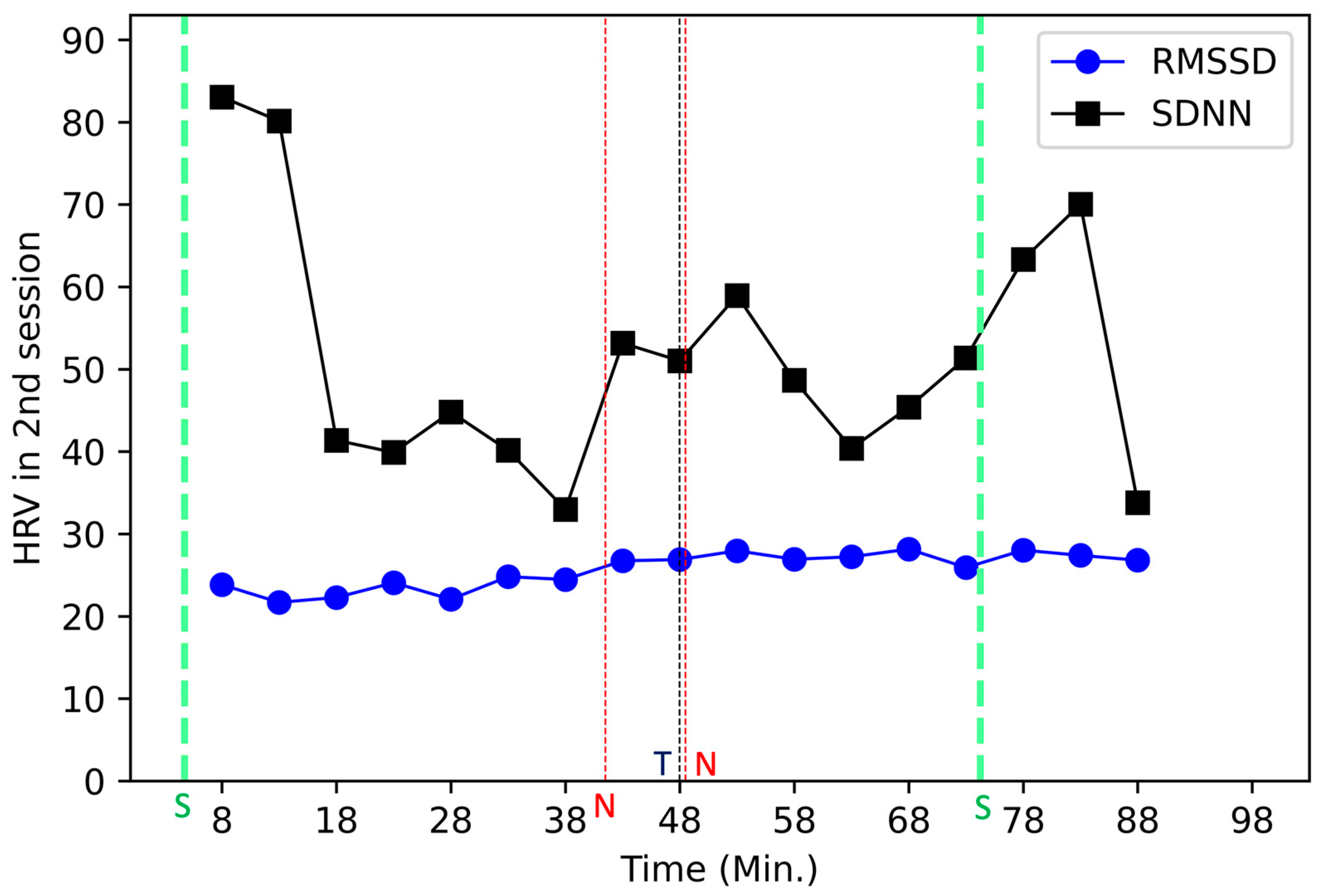

3.1.2. Session two: Cognitive reconstruction

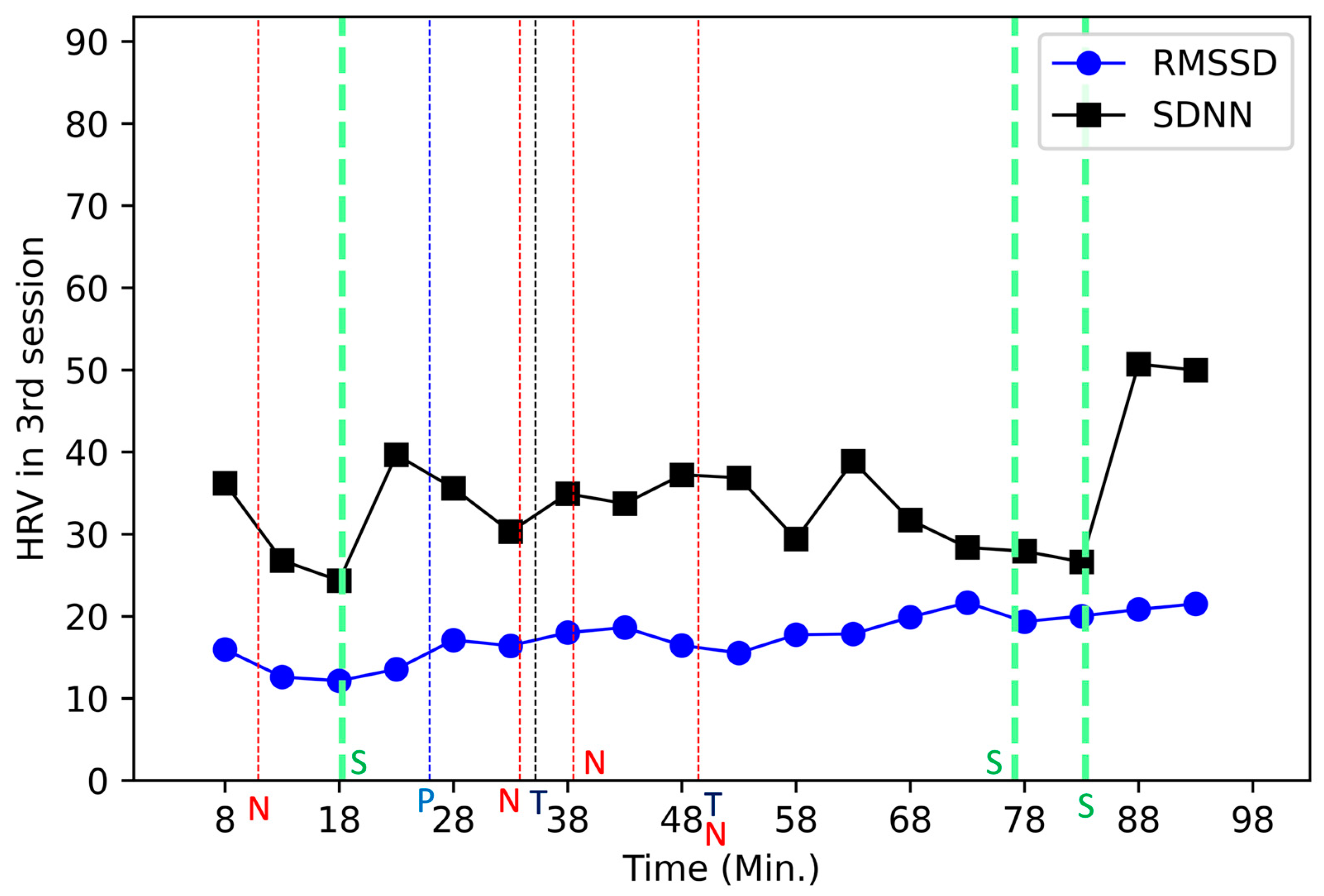

3.1.3. Session three: Sensory reconstruction and identifying resources

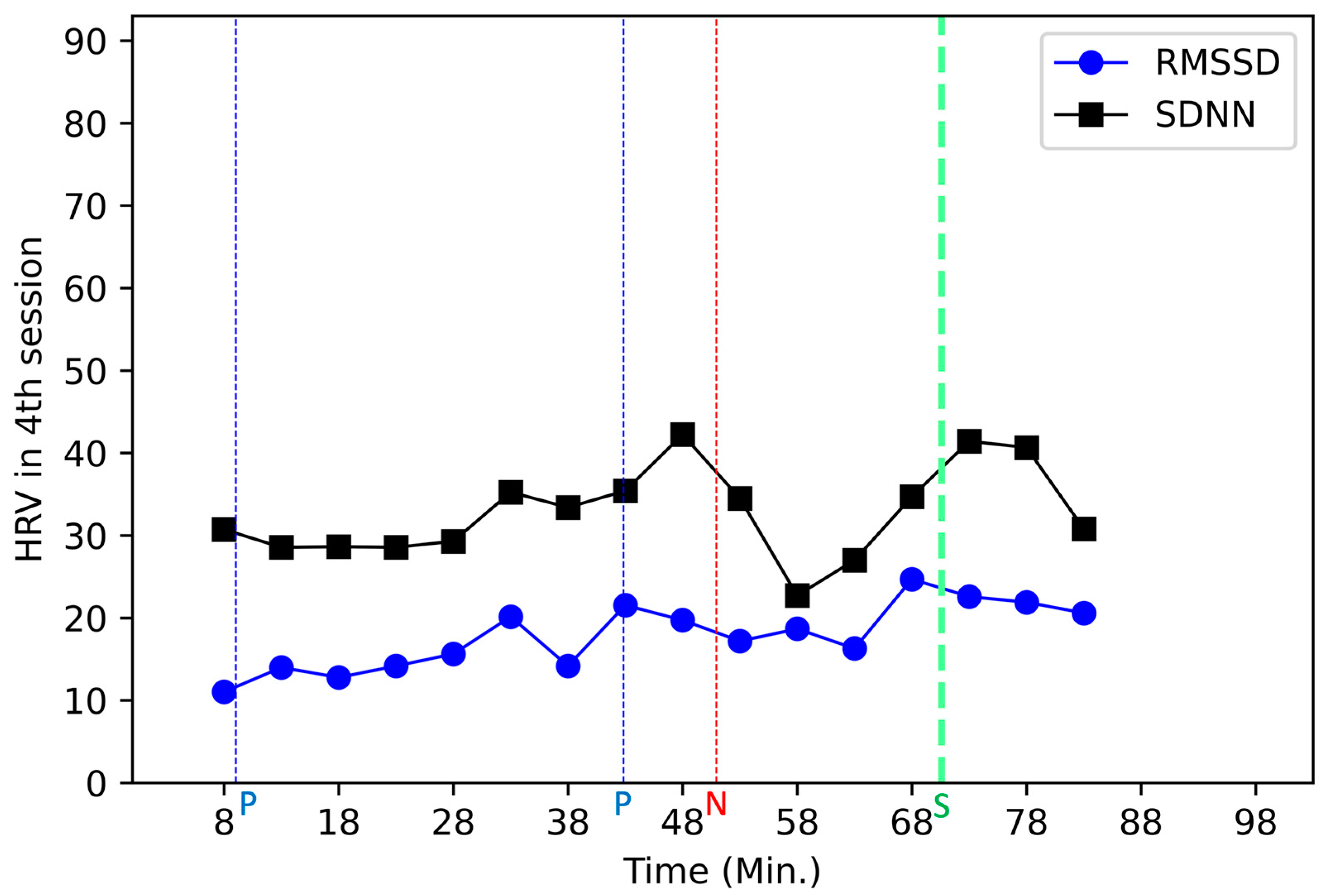

3.1.4. Session four: Confirming one’s own change, exploring self-management plan, and projecting one’s one future (going into the world)

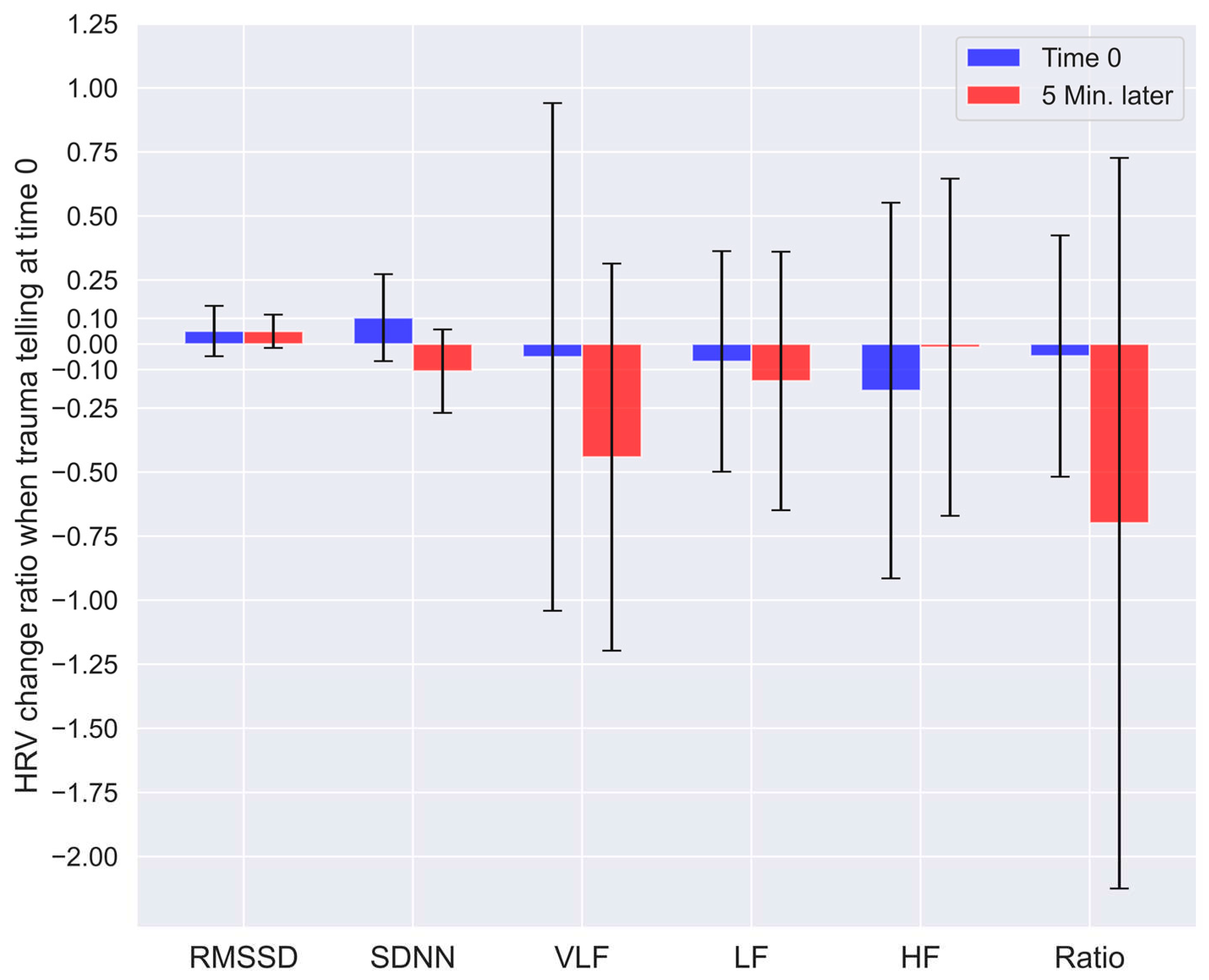

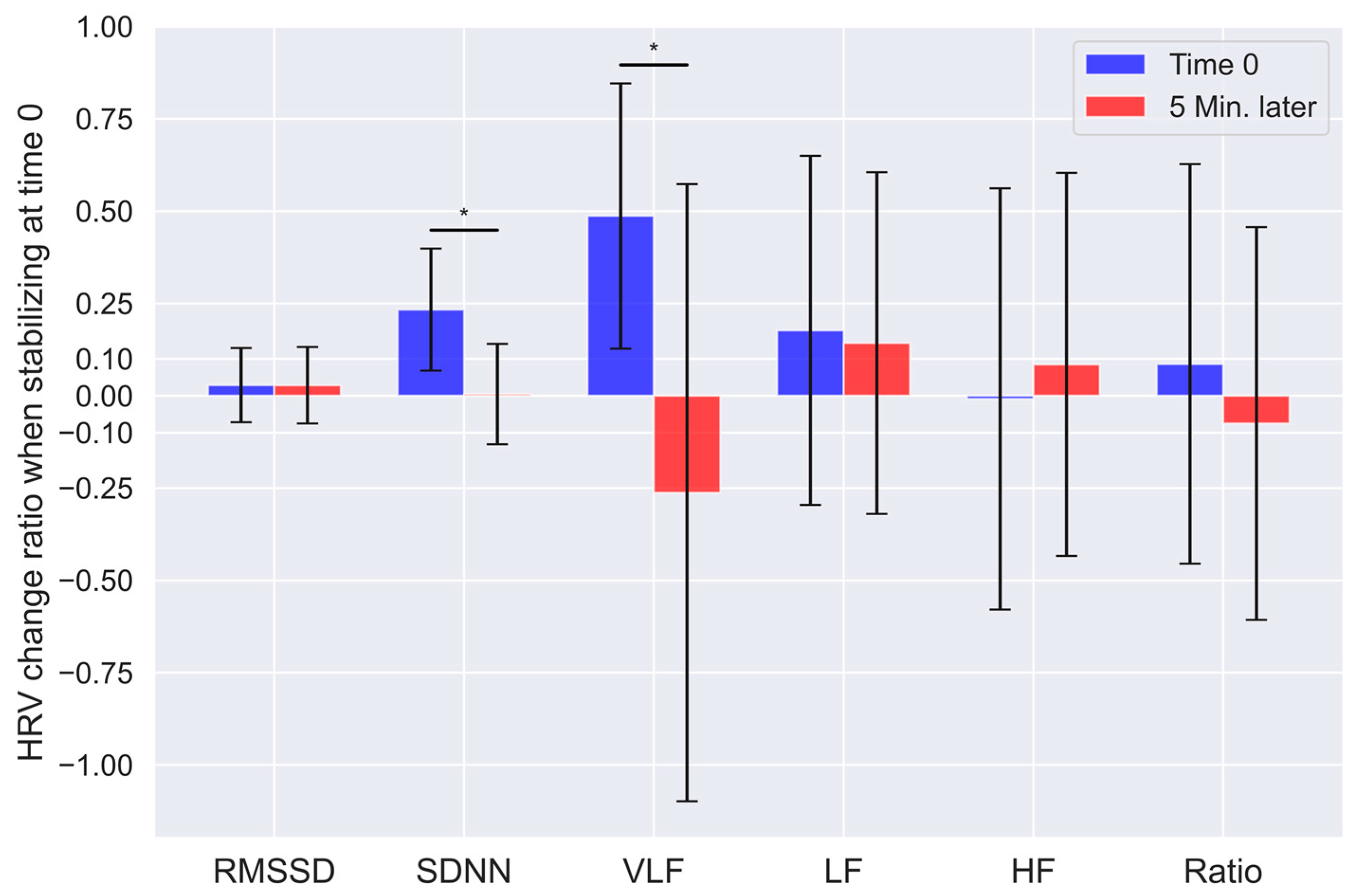

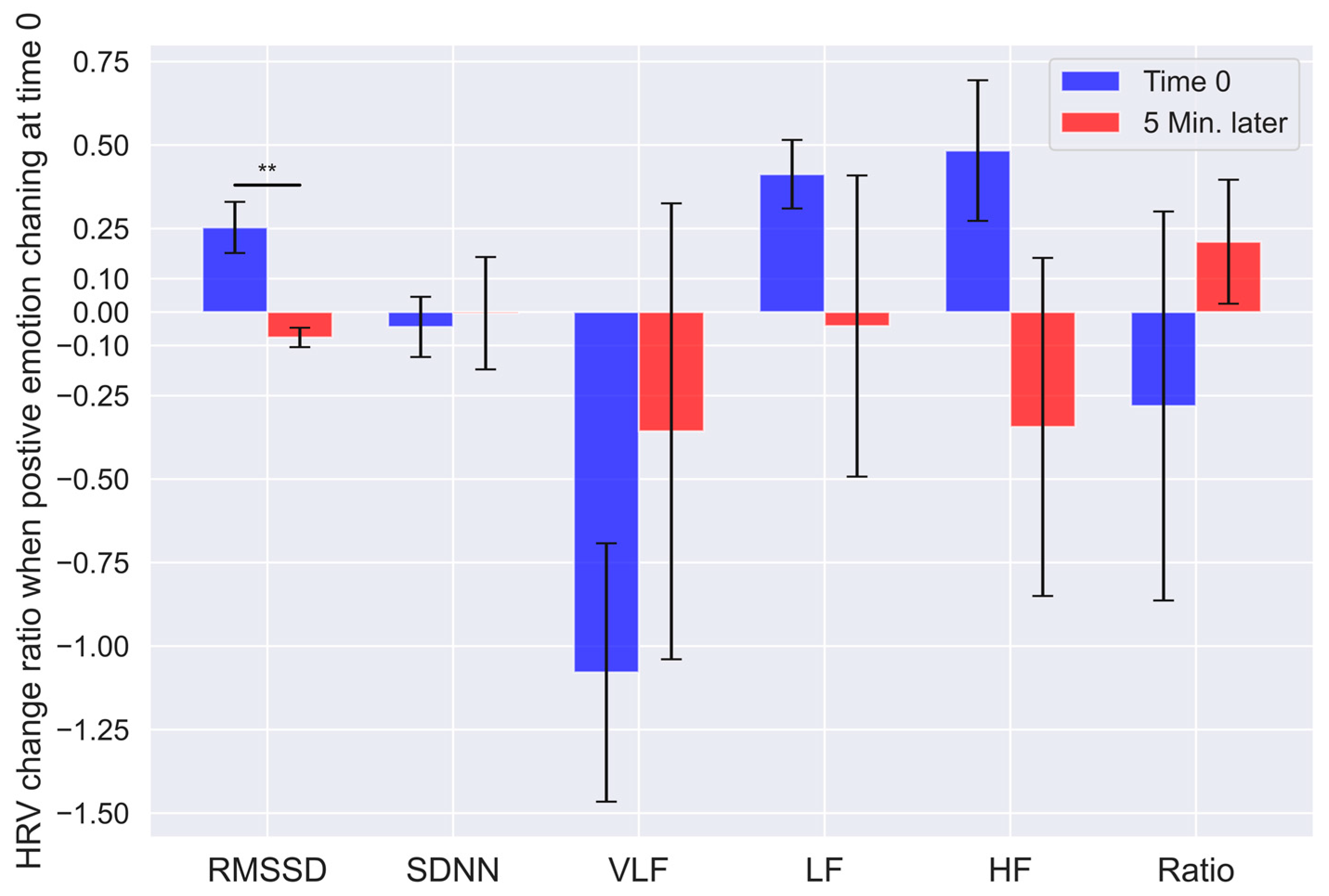

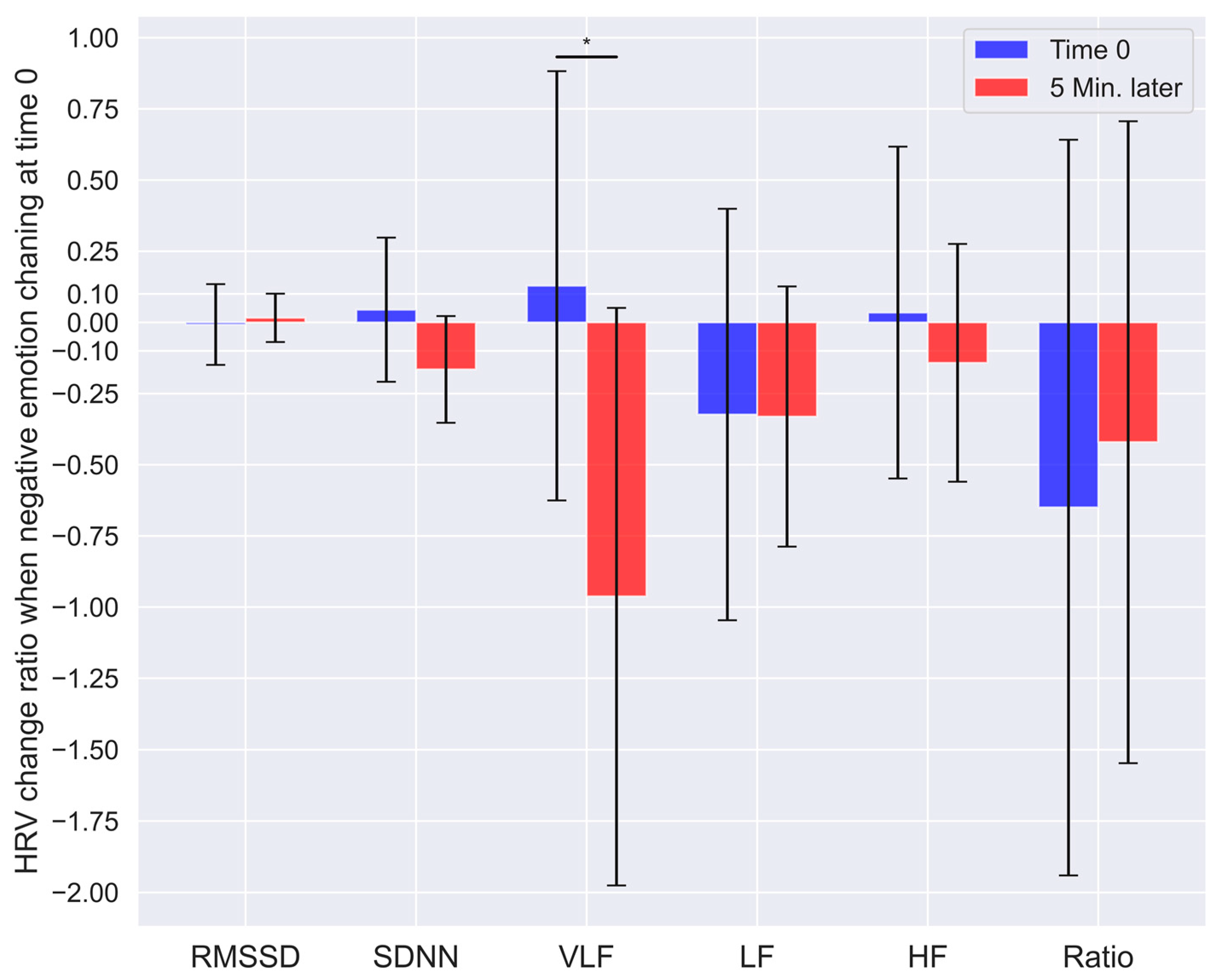

3.2. Statistical analysis of relation between the interventional event and the HRV change ratio

3.3. Change in the IES-R-K and AIS scale before, after, and 10 months after the proposed program

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herman, J.L. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1992, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terr, L.C. Childhood Traumas - an Outline and Overview. Am J Psychiat 1991, 148, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, B.v.d.; Pelcovitz, D. CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF THE STRUCTURED INTERVIEW FOR DISORDERS OF EXTREME STRESS (SIDES). Clinical Quarterly 1999, 8, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, C.A. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 2004, 41, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.L. Trauma and recovery, 2015 edition. ed.; BasicBooks: New York, 2015; pp. ix, 326 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Psychotherapy of Complex PTSD: Focus on a Phase-Based Approach. The Korean Journal of Psychology: General 2020, 39, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K. Differences in the Symptoms of Complex PTSD and PTSD in North Korean Defectors by Trauma Type. 2014, 4, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B.A.; Courtois, C.A. Editorial comments: Complex developmental trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2005, 18, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelcovitz, D.; van der Kolk, B.; Roth, S.; Mandel, F.; Kaplan, S.; Resick, P. Development of a criteria set and a structured interview for disorders of extreme stress (SIDES). Journal of Traumatic Stress 1997, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G.; Dansky, B.S.; Saunders, B.E.; Best, C.L. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1993, 61, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.-n. An Empirical Review of Complex Trauma. The Korean Journal of Psychology: General 2007, 26, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, H. Development of a trauma case formulation framework (TCFF): The case formulation approach for trauma-focused psychotherapy. Korean Journal Of Counseling And Psychotherapy 2016, 28, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, P.; Minton, K.; Pain, C. Trauma and the body : a sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy, 1st ed.; W.W. Norton: New York, 2006; pp. xxxiv, 345 p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Woo, J. Comparison of Smart Watch Based Pulse Rate Variability with Heart Rate Variability. Journal of Biomedical Engineering Research 2018, 39, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Na, Y.; Woo, J. Study on Listening Efforts Based on Heart Rate Variability. Journal of Biomedical Engineering Research 2019, 40, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. Heart Rate Variability in Stressful Events and Mental Disorder. Stress 2008, 16, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.-K.; Choi, S.-W.; Park, H.-i.; Seok, J.-H. Characteristics in Heart Rate Variability Associated with Early Life Stress in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Mood Emot 2017, 15, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bilchick, K.C.; Berger, R.D. Heart rate variability. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006, 17, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, A.; Geyer, M.A.; Baker, D.G.; Nievergelt, C.M.; O'Connor, D.T.; Risbrough, V.B.; Marine Resiliency Study, T. Heart rate variability characteristics in a large group of active-duty marines and relationship to posttraumatic stress. Psychosom Med 2014, 76, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, A.; Maihofer, A.X.; Baker, D.G.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Geyer, M.A.; Risbrough, V.B.; Marine Resiliency Study, T. Association of Predeployment Heart Rate Variability With Risk of Postdeployment Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Active-Duty Marines. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Camm, A.J. Heart rate variability; Futura Pub. Co.: Armonk, NY, 1995; pp. xiv, 543 p. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, G.G.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Eckberg, D.L.; Grossman, P.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Malik, M.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Porges, S.W.; Saul, J.P.; Stone, P.H.; et al. Heart rate variability: origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckberg, D.L. Sympathovagal balance: a critical appraisal. Circulation 1997, 96, 3224–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A.; Theus, S.A. Lower heart rate variability associated with military sexual trauma rape and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Res Nurs 2012, 14, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.J.; Lampert, R.; Goldberg, J.; Veledar, E.; Bremner, J.D.; Vaccarino, V. Posttraumatic stress disorder and impaired autonomic modulation in male twins. Biol Psychiatry 2013, 73, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulloch, H.; Greenman, P.S.; Tasse, V. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Cardiac Patients: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Considerations for Assessment and Treatment. Behav Sci (Basel) 2014, 5, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, R.M.; Freedland, K.E. Depression following myocardial infarction. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005, 27, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, H.; Benjamin, J.; Geva, A.B.; Matar, M.A.; Kaplan, Z.; Kotler, M. Autonomic dysregulation in panic disorder and in post-traumatic stress disorder: application of power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability at rest and in response to recollection of trauma or panic attacks. Psychiatry Res 2000, 96, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.L.; Minassian, A.; Paulus, M.P.; Geyer, M.A.; Perry, W. Heart rate variability in bipolar mania and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaspina, D.; Bruder, G.; Dalack, G.W.; Storer, S.; Van Kammen, M.; Amador, X.; Glassman, A.; Gorman, J. Diminished cardiac vagal tone in schizophrenia: associations to brain laterality and age of onset. Biol Psychiatry 1997, 41, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. Claude Bernard and the heart-brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009, 33, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Courtois, C.A.; Ford, J.D.; Green, B.L.; Alexander, P.; Briere, J.; Herman, J.L.; Lanius, R.; Stolbach, B.C.; Spinazzola, J.; et al. The ISTSS Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines for Complex PTSD in Adults. Available online: https://istss.org/ISTSS_Main/media/Documents/ISTSS-Expert-Concesnsus-Guidelines-for-Complex-PTSD-Updated-060315.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Kim, S.H.Y., K. L. A Validation Study of the Korean Version of the Complex Trauma Inventory. Journal of Rehabilitation Psychology 2020, 27, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P.; Keane, T.M. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD; Guilford Press: New York, 1997; p. xiv, 577 p. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, H.-J.; Kwon, T.-W.; Lee, S.-M.; Kim, T.-H.; Choi, M.-R.; Cho, S.J. A Study on Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised. JOURNAL OF THE KOREAN NEUROPSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION 2005, 44, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res 2000, 48, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Polar. Polar H10 User Manual. Available online: https://support.polar.com/e_manuals/h10-heart-rate-sensor/polar-h10-user-manual-english/manual.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Gomes, P.; Margaritoff, P.; Silva, H. pyHRV: Development and evaluation of an open-source python toolbox for heart rate variability (HRV); 2019; pp. 822–828. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, P. pyHRV - OpenSource Python Toolbox for Heart Rate Variability. Available online: https://pyhrv.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzman, J.B.; Bridgett, D.J. Heart rate variability indices as bio-markers of top-down self-regulatory mechanisms: A meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017, 74, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative Case Studies. In The Sage handbook of qualitative research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2005; pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

| Before | After | 10 moths after | ||

| IES-R-K (Full score: 88) |

Re-experiencing | 23 | 10 | 15 |

| Hyperarousal | 21 | 19 | 20 | |

| Sleep, emotion, dissociation |

14 | 15 | 10 | |

| Avoidance | 24 | 17 | 17 | |

| Summation | 60 | 43 | 40 | |

| AIS (Full score: 24) |

10 | 7 | 6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).