Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1 Clinical Features and Prevalence in the Indigenous Population of Western Canada

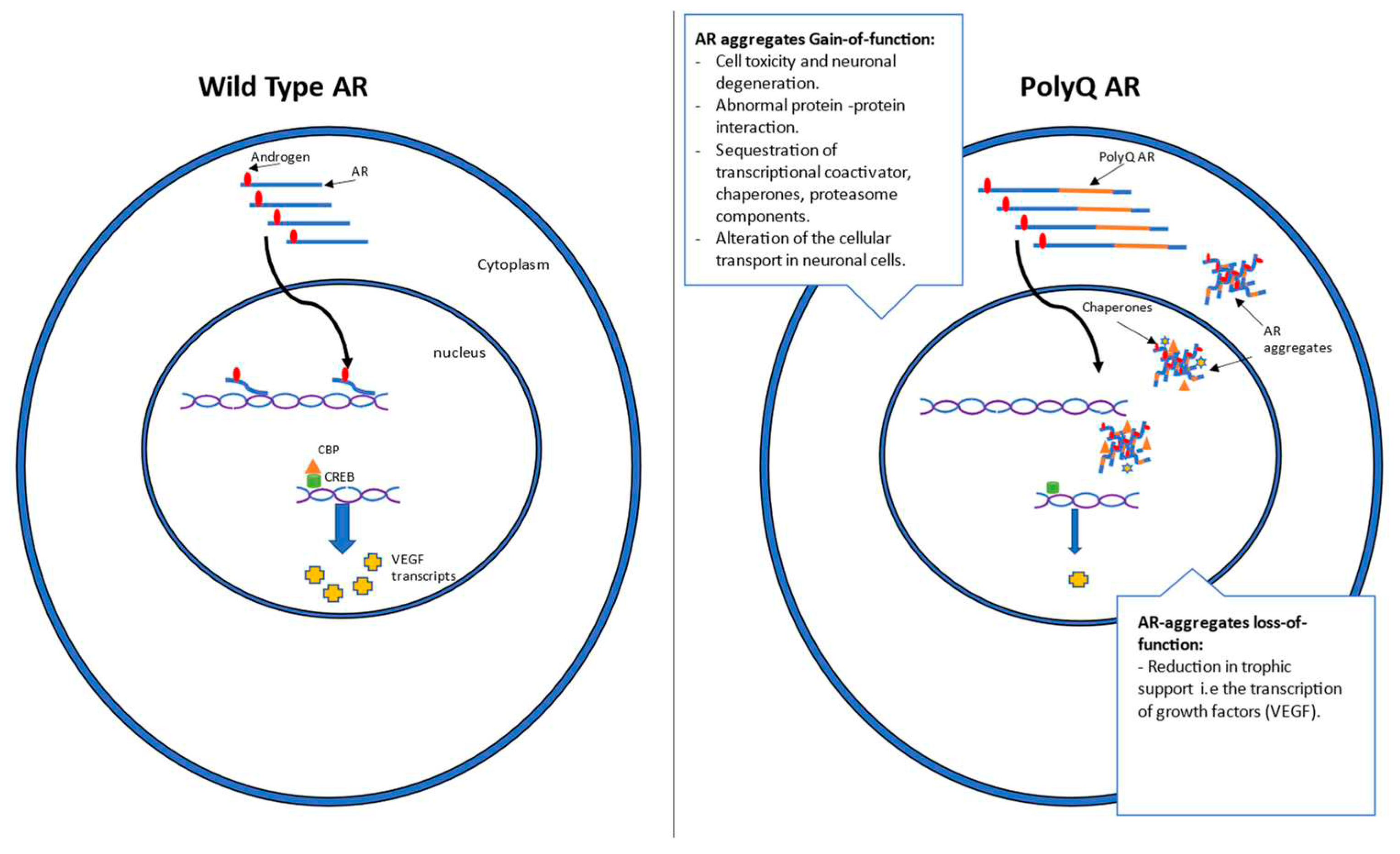

1.2 Mechanism and genetics

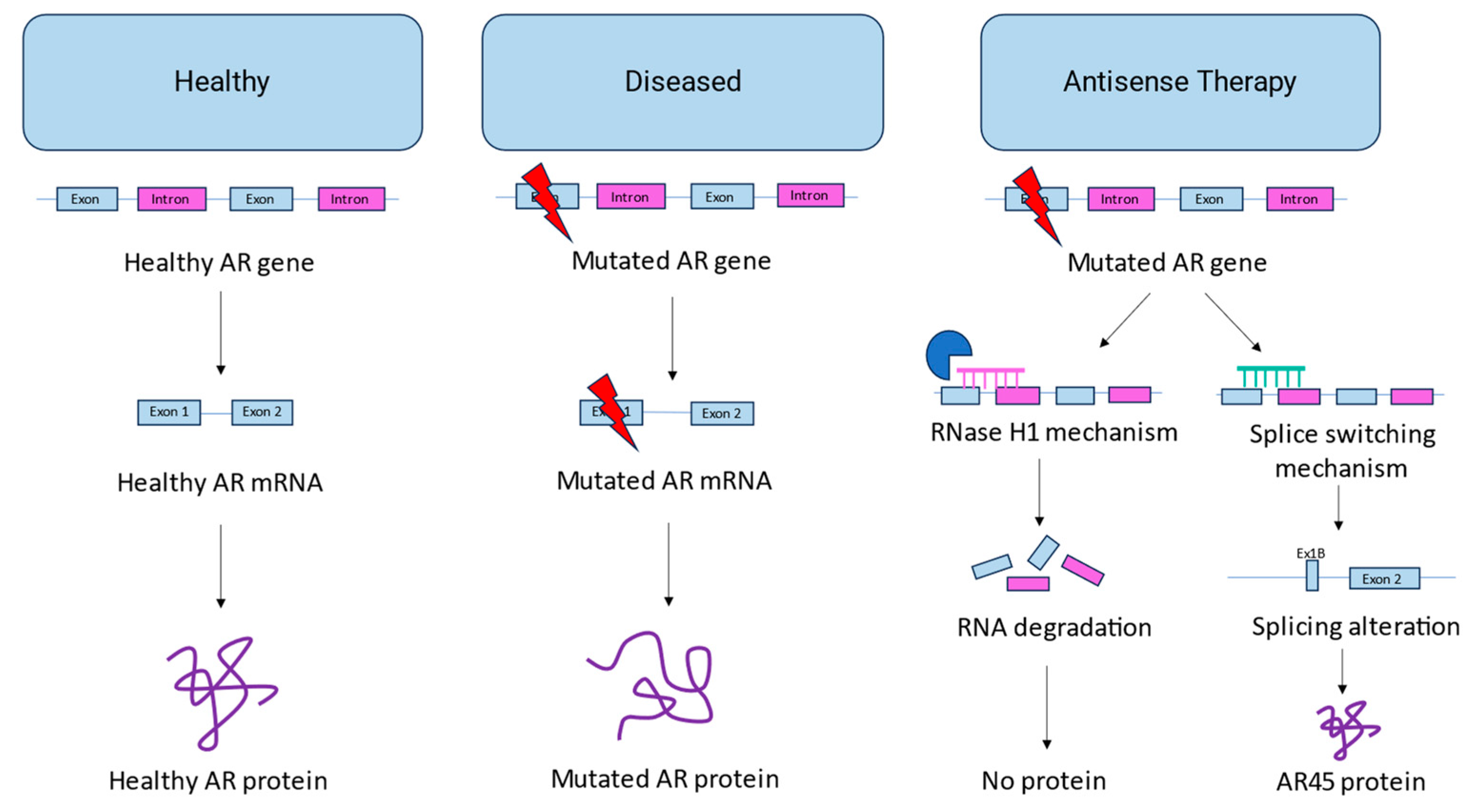

2. Current antisense approaches for SBMA

2.1. AON-mediated androgen receptor knockdown

2.2. AON-mediated androgen receptor splice switching

3. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennedy, W.R.; Alter, M.; Sung, J.H. Progressive Proximal Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy of Late Onset. Neurology 1968, 18, 671–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banno, H.; Katsuno, M.; Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, F.; Sobue, G. Pathogenesis and Molecular Targeted Therapy of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA). Cell Tissue Res 2012, 349, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsuta, N.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, M.; Banno, H.; Suzuki, K.; Katsuno, M.; Tanaka, F.; Tamakoshi, A.; Sobue, G. Natural History of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA): A Study of 223 Japanese Patients. Brain 2006, 129, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejager, S.; Bry-Gauillard, H.; Bruckert, E.; Eymard, B.; Salachas, F.; LeGuern, E.; Tardieu, S.; Chadarevian, R.; Giral, P.; Turpin, G. A Comprehensive Endocrine Description of Kennedy’s Disease Revealing Androgen Insensitivity Linked to CAG Repeat Length. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87, 3893–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbohm, A.; Hirsch, S.; Volk, A.E.; Grehl, T.; Grosskreutz, J.; Hanisch, F.; Herrmann, A.; Kollewe, K.; Kress, W.; Meyer, T.; et al. The Metabolic and Endocrine Characteristics in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. J Neurol 2018, 265, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querin, G.; Bertolin, C.; Da Re, E.; Volpe, M.; Zara, G.; Pegoraro, E.; Caretta, N.; Foresta, C.; Silvano, M.; Corrado, D.; et al. Non-Neural Phenotype of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy: Results from a Large Cohort of Italian Patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016, 87, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini-Pesenti, F.; Querin, G.; Martini, C.; Mareso, S.; Sacerdoti, D. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Cohort of Italian Patients with Spinal-Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Acta Myologica 2018, 37, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, F.; Katsuno, M.; Banno, H.; Suzuki, K.; Adachi, H.; Sobue, G. Current Status of Treatment of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Neural Plast 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradat, P.F.; Bernard, E.; Corcia, P.; Couratier, P.; Jublanc, C.; Querin, G.; Morélot Panzini, C.; Salachas, F.; Vial, C.; Wahbi, K.; et al. The French National Protocol for Kennedy’s Disease (SBMA): Consensus Diagnostic and Management Recommendations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2020 15:1 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, D.; Sabadini, R.; Ferlini, A.; Torrente, I. Epidemiological Survey of X-Linked Bulbar and Spinal Muscular Atrophy, or Kennedy Disease, in the Province of Reggio Emilia, Italy. Eur J Epidemiol 2001, 17, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.; Udd, B.; Juvonen, V.; Andersen, P.M.; Cederquist, K.; Davis, M.; Gellera, C.; Kölmel, C.; Ronnevi, L.O.; Sperfeld, A.D.; et al. Multiple Founder Effects in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA, Kennedy Disease) around the World. European Journal of Human Genetics 2001 9:6 2001, 9, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leckie, J.N.; Joel, M.M.; Martens, K.; King, A.; King, M.; Korngut, L.W.; Koning, A.P.J. de; Pfeffer, G.; Schellenberg, K.L. Highly Elevated Prevalence of Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy in Indigenous Communities in Canada Due to a Founder Effect. Neurol Genet 2021, 7, e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, A.; Udd, B.; Juvonen, V.; Andersen, P.M.; Cederquist, K.; Ronnevi, L.O.; Sistonen, P.; Sörensen, S.A.; Tranebjærg, L.; Wallgren-Pettersson, C.; et al. Founder Effect in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA) in Scandinavia. European Journal of Human Genetics 2000 8:8 2000, 8, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Doyu, M.; Ito, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Mitsuma, T.; Abe, K.; Aoki, M.; Itoyama, Y.; Fischbeck, K.H.; Sobue, G. Founder Effect in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA). Hum Mol Genet 1996, 5, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Smith, A.; Gracey, M. Indigenous Health Part 2: The Underlying Causes of the Health Gap. The Lancet 2009, 374, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.; Miller, A.P.; Quesnel-Vallée, A.; Caron, N.R.; Vissandjée, B.; Marchildon, G.P. Canada’s Universal Health-Care System: Achieving Its Potential. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1718–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, N.R.; Chongo, M.; Hudson, M.; Arbour, L.; Wasserman, W.W.; Robertson, S.; Correard, S.; Wilcox, P. Indigenous Genomic Databases: Pragmatic Considerations and Cultural Contexts. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 529095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, E.L.; Loy, C.J.; Sim, K.S. Androgen Receptor Gene and Male Infertility. Hum Reprod Update 2003, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.Z.; Wardell, S.E.; Burnstein, K.L.; Defranco, D.; Fuller, P.J.; Giguere, V.; Hochberg, R.B.; Mckay, L.; Renoir, J.M.; Weigel, N.L.; et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXV. The Pharmacology and Classification of the Nuclear Receptor Superfamily: Glucocorticoid, Mineralocorticoid, Progesterone, and Androgen Receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2006, 58, 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, I.; Gliozzi, A.; Rusmini, P.; Sau, D.; Crippa, V.; Simonini, F.; Onesto, E.; Bolzoni, E.; Poletti, A. The Role of the Polyglutamine Tract in Androgen Receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 108, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Goss, S.J.; Lubahn, D.B.; Joseph, D.R.; Wilson, E.M.; French, F.S.; Willard, H.F. Androgen Receptor Locus on the Human X Chromosome: Regional Localization to Xq11-12 and Description of a DNA Polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet 1989, 44, 264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lubahn, D.B.; Joseph, D.R.; Sullivan, P.M.; Willard, H.F.; French, F.S.; Wilson, E.M. Cloning of Human Androgen Receptor Complementary DNA and Localization to the X Chromosome. Science (1979) 1988, 240, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Kokontis, J.; Liao, S. Molecular Cloning of Human and Rat Complementary DNA Encoding Androgen Receptors. Science (1979) 1988, 240, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Laar, J.H.; Vries, J.B. de; Voorhorst-Ogink, M.M.; Brinkmann, A.O. The Human Androgen Receptor Is a 110 KDa Protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1989, 63, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, G.G.J.M.; Faber, P.W.; Van Rooij, H.C.J.; Van der Korput, J.A.G.M.; Ris-Stalpers, C.; Klaassen, P.; Trapman, J.; Brinkmann, A.O. STRUCTURAL ORGANIZATION OF THE HUMAN ANDROGEN RECEPTOR GENE. J Mol Endocrinol 1989, 2, R1–R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.J.; O’Malley, B.W. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Steroid/Thyroid Receptor Superfamily Members. Annu Rev Biochem 1994, 63, 451–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, A.O. Molecular Basis of Androgen Insensitivity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001, 179, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbeck, K.H.; Lieberman, A.; Bailey, C.K.; Abel, A.; Merry, D.E. Androgen Receptor Mutation in Kennedy’s Disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 1999, 354, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratta, P.; Collins, T.; Pemble, S.; Nethisinghe, S.; Devoy, A.; Giunti, P.; Sweeney, M.G.; Hanna, M.G.; Fisher, E.M.C. Sequencing Analysis of the Spinal Bulbar Muscular Atrophy CAG Expansion Reveals Absence of Repeat Interruptions. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 443.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyas, C.A.; La Spada, A.R. The CAG–Polyglutamine Repeat Diseases: A Clinical, Molecular, Genetic, and Pathophysiologic Nosology. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 147, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmann, E.P. Molecular Biology of the Androgen Receptor. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ing, N.H.; Beekman, J.M.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tsai, M.-J.; O’malleyl, B.W.; Sagami, I.; Tsai, S.Y.; Wang, H.; Tsii, M.-J.; Malley, O. ’; et al. THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Members of the Steroid Hormone Receptor Superfamily Interact with TFIIB (S300-11)" The S300-I1 Factor Was Discovered as an Activator of Ovalbumin Gene Transcription with the Chicken Oval-Bumin Upstream Promoter-Transcription Factor (COUP-T%’ Although S300-I1 Does Not Bind DNA Selec-Tively, It Stabilizes the Binding of COUP-TF to Its Cis-Element. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267, 17617–17623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniahmad, A.; Ha, I.; Reinberg, D.; Tsai, S.; Tsai, M.J.; O’Malley, B.W. Interaction of Human Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta with Transcription Factor TFIIB May Mediate Target Gene Derepression and Activation by Thyroid Hormone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 8832–8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brou, C.; Chaudhary, S.; Davidson, I.; Lutz, Y.; Wu, J.; Egly, J.M.; Tora, L.; Chambon, P. Distinct TFIID Complexes Mediate the Effect of Different Transcriptional Activators. EMBO J 1993, 12, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brou, C.; Wu, J.; Ali, S.; Scheer, E.; Lang, C.; Davidson, I.; Chambon, P.; Tora, L. Different TBP-Associated Factors Are Required for Mediating the Stimulation of Transcription in Vitro by the Acidic Transactivator GAL-VP16 and the Two Nonacidic Activation Functions of the Estrogen Receptor. Nucleic Acids Res 1993, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcewan, I.J.; Gustafsson, J.Å. Interaction of the Human Androgen Receptor Transactivation Function with the General Transcription Factor TFIIF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, I.G.; Chakravarti, D.; Juguilon, H.; Romo, A.; Evans, R.M. Interactions between the Retinoid X Receptor and a Conserved Region of the TATA-Binding Protein Mediate Hormone-Dependent Transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.S.; Fraley, G.S.; Damien, V.; Woodke, L.B.; Zapata, F.; Sopher, B.L.; Plymate, S.R.; La Spada, A.R. Loss of Endogenous Androgen Receptor Protein Accelerates Motor Neuron Degeneration and Accentuates Androgen Insensitivity in a Mouse Model of X-Linked Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2006, 15, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Glutamine Repeats and Neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000, 23, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A. When More Is Less: Pathogenesis of Glutamine Repeat Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neuron 1995, 15, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, T.J.; Henley, J.M. Fighting Polyglutamine Disease by Wrestling with SUMO. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Nakagomi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Merry, D.E.; Tanaka, F.; Doyu, M.; Mitsuma, T.; Hashizume, Y.; Fischbeck, K.H.; Sobue, G. Nonneural Nuclear Inclusions of Androgen Receptor Protein in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Am J Pathol 1998, 153, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, F.J.; Merry, D.E. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutics for SBMA/Kennedy’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2019 16:4 2019, 16, 928–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.; Watt, K.; Kelly, S.M.; Clark, C.; Price, N.C.; McEwan, I.J. Consequences of Poly-Glutamine Repeat Length for the Conformation and Folding of the Androgen Receptor Amino-Terminal Domain. J Mol Endocrinol 2008, 41, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, A.; Topal, B.; Kunze, M.B.A.; Aranda, J.; Chiesa, G.; Mungianu, D.; Bernardo-Seisdedos, G.; Eftekharzadeh, B.; Gairí, M.; Pierattelli, R.; et al. Side Chain to Main Chain Hydrogen Bonds Stabilize a Polyglutamine Helix in a Transcription Factor. Nature Communications 2019 10:1 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perutz, M.F.; Johnson, T.; Suzuki, M.; Finch, J.T. Glutamine Repeats as Polar Zippers: Their Possible Role in Inherited Neurodegenerative Diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H. Human Genetic Diseases Due to Codon Reiteration: Relationship to an Evolutionary Mechanism. Cell 1993, 74, 955–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morfini, G.; Pigino, G.; Szebenyi, G.; You, Y.; Pollema, S.; Brady, S.T. JNK Mediates Pathogenic Effects of Polyglutamine-Expanded Androgen Receptor on Fast Axonal Transport. Nature Neuroscience 2006 9:7 2006, 9, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rgyi Szebenyi, G.; Morfini, G.A.; Babcock, A.; Gould, M.; Selkoe, K.; Stenoien, D.L.; Young, M.; Faber, P.W.; Macdonald, M.E.; Mcphaul, M.J.; et al. Neuropathogenic Forms of Huntingtin and Androgen Receptor Inhibit Fast Axonal Transport Lengths of 20-25 Glutamines to Pathological Expansions of 40. Neurological Symptoms Typically Appear in Mid-Life, Although Longer PolyQ Repeats Are Associated with Earlier Onset of Symptoms. Aside from the PolyQ Tracts, Gene Products Associated with PolyQ Diseases Exhibit Minimal Sequence Homology. Knockouts of Genes En-Coding PolyQ-Containing Proteins Result in Different Phe-1. Neuron 2003, 40, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Piccioni, F.; Pinton, P.; Simeoni, S.; Pozzi, P.; Fascio, U.; Vismara, G.; Martini, L.; Rizzuto, R.; Poletti, A. Androgen Receptor with Elongated Polyglutamine Tract Forms Aggregates That Alter Axonal Trafficking and Mitochondrial Distribution in Motor Neuronal Processes. The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2002, 16, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopher, B.L.; Thomas, P.S.; Lafevre-Bernt, M.A.; Holm, I.E.; Wilke, S.A.; Ware, C.B.; Jin, L.W.; Libby, R.T.; Ellerby, L.M.; La Spada, A.R. Androgen Receptor YAC Transgenic Mice Recapitulate SBMA Motor Neuronopathy and Implicate VEGF164 in the Motor Neuron Degeneration. Neuron 2004, 41, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooke, S.T.; Baker, B.F.; Crooke, R.M.; Liang, X. hai Antisense Technology: An Overview and Prospectus. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021 20:6 2021, 20, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamecnik, P.C.; Stephenson, M.L. Inhibition of Rous Sarcoma Virus Replication and Cell Transformation by a Specific Oligodeoxynucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978, 75, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Lima, W.F.; Zhang, H.; Fan, A.; Sun, H.; Crooke, S.T. Determination of the Role of the Human RNase H1 in the Pharmacology of DNA-like Antisense Drugs. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 17181–17189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, M.; Ashizawa, A.T. The Challenges and Strategies of Antisense Oligonucleotide Drug Delivery. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, M.A.; Hastings, M.L. Splice-Switching Antisense Oligonucleotides as Therapeutic Drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A.P.; Yu, Z.; Murray, S.; Peralta, R.; Low, A.; Guo, S.; Yu, X.X.; Cortes, C.J.; Bennett, C.F.; Monia, B.P.; et al. Peripheral Androgen Receptor Gene Suppression Rescues Disease in Mouse Models of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Cell Rep 2014, 7, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahashi, K.; Katsuno, M.; Hung, G.; Adachi, H.; Kondo, N.; Nakatsuji, H.; Tohnai, G.; Iida, M.; Bennett, F.F.; Sobue, G. Silencing Neuronal Mutant Androgen Receptor in a Mouse Model of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2015, 24, 5985–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, M.M.; Pepers, B.A.; van Deutekom, J.C.T.; Mulders, S.A.M.; den Dunnen, J.T.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; van Ommen, G.J.B.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C. Targeting Several CAG Expansion Diseases by a Single Antisense Oligonucleotide. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamy, F.; Brondani, V.; Spoerri, R.; Rigo, S.; Stamm, C.; Klimkait, T. Specific Block of Androgen Receptor Activity by Antisense Oligonucleotides. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2003, 6, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Loriot, Y.; Beraldi, E.; Zhang, F.; Wyatt, A.W.; Nakouzi, N. Al; Mo, F.; Zhou, T.; Kim, Y.; Monia, B.P.; et al. Generation 2.5 Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting the Androgen Receptor and Its Splice Variants Suppress Enzalutamide-Resistant Prostate Cancer Cell Growth. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 1675–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, J.; Wang, Q.; Yan, L.; Wang, L.; Xing, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Delivering Antisense Oligonucleotides across the Blood-Brain Barrier by Tumor Cell-Derived Small Apoptotic Bodies. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2004929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kong, J.; Ge, X.; Mao, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. An Antisense Oligonucleotide-Loaded Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrable Nanoparticle Mediating Recruitment of Endogenous Neural Stem Cells for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 4414–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Naito, M.; Ogura, S.; Toh, K.; Hayashi, K.; Kim, B.S.; Fukushima, S.; Anraku, Y.; Miyata, K.; et al. Systemic Brain Delivery of Antisense Oligonucleotides across the Blood–Brain Barrier with a Glucose-Coated Polymeric Nanocarrier. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2020, 59, 8173–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echevarría, L.; Aupy, P.; Goyenvalle, A. Exon-Skipping Advances for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, R163–R172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, J.; Jearawiriyapaisarn, N.; Kole, R. Therapeutic Potential of Splice-Switching Oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotides 2009, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Casimersen: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierlega, K.; Yokota, T. Optimization of Antisense-Mediated Exon Skipping for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Gene Ther 2020, 27, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurster, C.D.; Ludolph, A.C. Nusinersen for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens-Fath, I.; Politz, O.; Geserick, C.; Haendler, B. Androgen Receptor Function Is Modulated by the Tissue-Specific AR45 Variant. FEBS J 2005, 272, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.M.; Mcphaul, M.J. A and B Forms of the Androgen Receptor Are Present in human Genital Skin Fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehm, S.M.; Tindall, D.J. Alternatively Spliced Androgen Receptor Variants. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011, 18, R183–R196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, A.; Coleman, I.; Yuan, W.; Sprenger, C.; Dolling, D.; Rodrigues, D.N.; Russo, J.W.; Figueiredo, I.; Bertan, C.; Seed, G.; et al. Androgen Receptor Splice Variant-7 Expression Emerges with Castration Resistance in Prostate Cancer. J Clin Invest 2018, 129, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Lu, C.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Nakazawa, M.; Roeser, J.C.; Chen, Y.; Mohammad, T.A.; Chen, Y.; Fedor, H.L.; et al. AR-V7 and Resistance to Enzalutamide and Abiraterone in Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Karsh, L.I.; Nissenblatt, M.J.; Canfield, S.E. Androgen Receptor Splice Variant, AR-V7, as a Biomarker of Resistance to Androgen Axis-Targeted Therapies in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2020, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.F.; Forouhan, M.; Roberts, T.C.; Dabney, J.; Ellerington, R.; Speciale, A.A.; Manzano, R.; Lieto, M.; Sangha, G.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Gene Therapy with AR Isoform 2 Rescues Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy Phenotype by Modulating AR Transcriptional Activity. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, K.A.; Keegan, N.P.; McIntosh, C.S.; Aung-Htut, M.T.; Zaw, K.; Greer, K.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D. Induction of Cryptic Pre-MRNA Splice-Switching by Antisense Oligonucleotides. Scientific Reports 2021 11:1 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.R.Q.; Woo, S.; Melo, D.; Huang, Y.; Dzierlega, K.; Shah, M.N.A.; Aslesh, T.; Roshmi, R.R.; Echigoya, Y.; Maruyama, R.; et al. Development of DG9 Peptide-Conjugated Single- and Multi-Exon Skipping Therapies for the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumpra, M.K.; Fukumoto, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeda, S.; Wood, M.J.A.; Aoki, Y. Peptide-Conjugate Antisense Based Splice-Correction for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Other Neuromuscular Diseases. EBioMedicine 2019, 45, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, H.M.; Moulton, J.D. Morpholinos and Their Peptide Conjugates: Therapeutic Promise and Challenge for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2010, 1798, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).