Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Body morphology

2.2.2. Displacement Skills

2.2.3. Problematic Behaviors

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

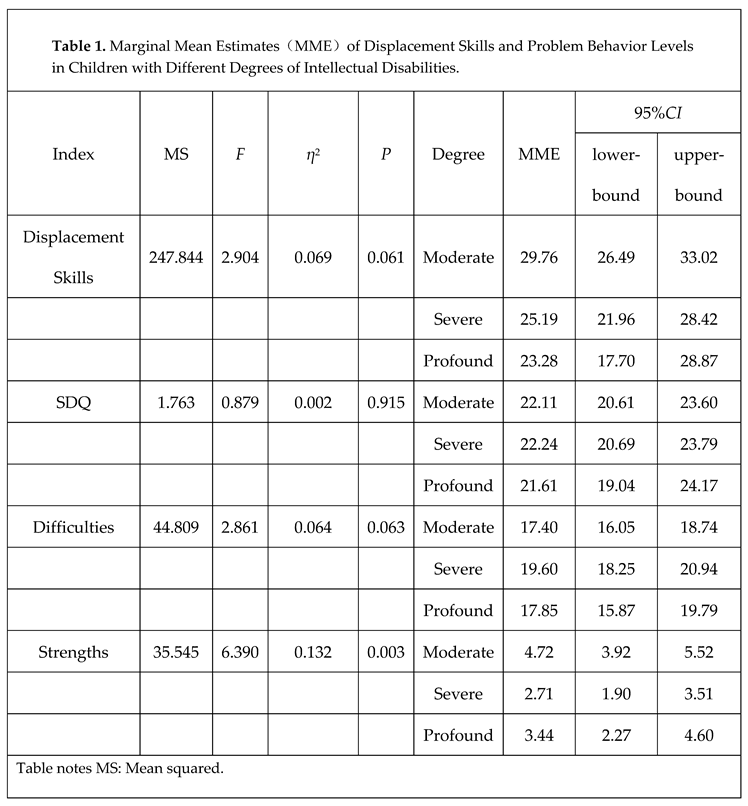

3.1. Analysis of displacement skills and problem behaviors in children with different levels of ID.

3.1.1. Displacement Skills

3.1.2. Problem Behaviors

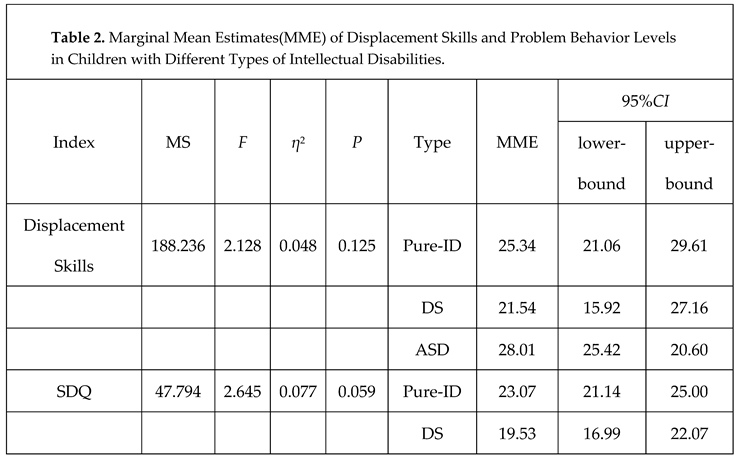

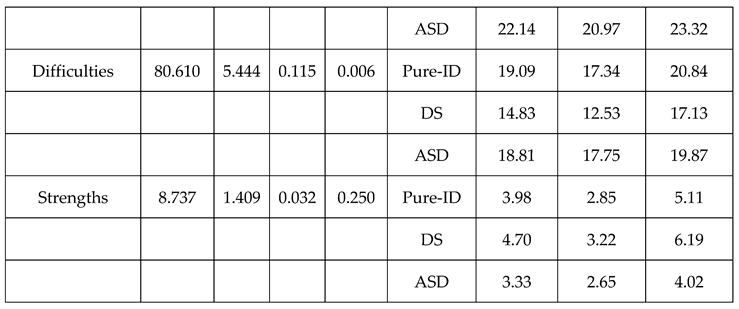

3.2. Analysis of displacement skills and problem behaviors in children with different types of ID.

3.2.1. Displacement Skills

3.2.2. Problem Behaviors

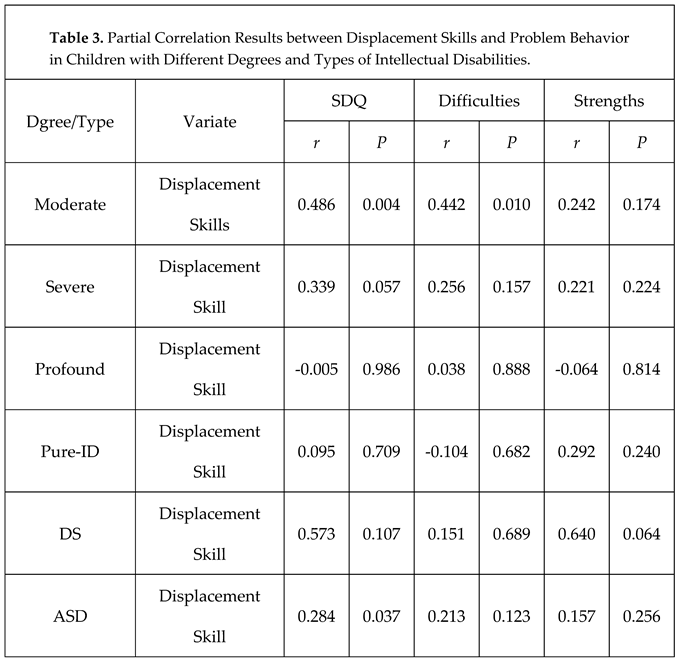

3.2.3. Correlation analysis of displacement skills and problematic behaviors in children with ID

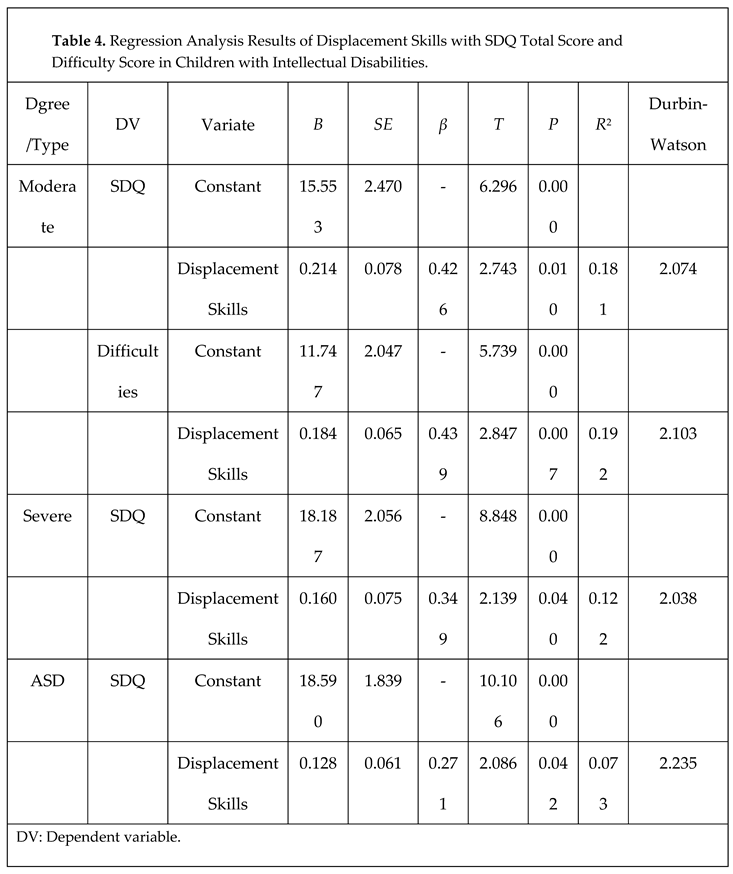

3.2.4. Multivariate linear regression analysis of the impact of displacement skills on problematic behaviors in children with ID

4. Discussion

4.1. Children with varying degrees of ID exhibit differences in their displacement skills and problem behaviors

4.2. Children with different types of ID exhibit differences in their displacement skills and problem behaviors

4.3. The relationship between displacement skills and problem behavior in children with ID

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matson, J.L.; Dixon, D.R.; Matson, M.L.; Logan, J.R. Classifying mental retardation and specific strength and deficit areas in severe and profoundly mentally retarded persons with the MESSIER. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2005, 26, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzhao, Z.; Yang, C. A Study on the Design Strategies for School Space of Special Needs Based on the Characteristics of Mentally Retarded Students. Architectural Journal. 2017, (05), 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, A.J.d.C.; Pinto, I.P.; Leijsten, N.; Ruiterkamp-Versteeg, M.; Pfundt, R.; de Leeuw, N.; da Cruz, A.D.; Minasi, L.B. Diagnostic yield of patients with undiagnosed intellectual disability, global developmental delay and multiples congenital anomalies using karyotype, microarray analysis, whole exome sequencing from Central Brazil. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0266493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemaker, E.; Hofmann, V.; Müller, C.M. Prosocial behavior in students with intellectual disabilities: Individual level predictors and the role of the classroom peer context. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0281598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taanila, A.; Ebeling, H.; Heikura, U. Behavioral problems of 8-year-old children with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Pediatric Neurology. 2013, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters, M.; Evenhuis, H.M.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M. Physical fitness of children and adolescents with moderate to severe intellectual disabilities. Disabil. Rehabilitation 2019, 42, 2542–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lier, P.A.C.; Vitaro, F.; Barker, E.D.; Brendgen, M.; Tremblay, R.E.; Boivin, M. Peer Victimization, Poor Academic Achievement, and the Link Between Childhood Externalizing and Internalizing Problems. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.A.; Sanford, C.B. Test of gross motor development; Pro-ed: Austin, TX, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, L.A. Exploration of reading interest and emergent literacy skills of children with down syndrome. International Journal of Special Education 2021, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L.M.; Beurden, E.V.; Morgan, P.J.; Lyndon, O.B.; John, R.B. Childhood Motor Skill Proficiency as a Predictor of Adolescent Physical Activity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008, 44, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwhy, J.D.; Ozmun, J.C.; Gallahue, D.L. Under-standing Motor Development:Infants, Children, Adolescent, Adults; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, USA, 2019; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gkotzia, E.; Venetsanou, F.; Kambas, A. EPJ Motor proficiency of children with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities: a review. 2017, 9, 46–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Z.; Dandan, W.; Xueping, W. Influence of Fundamental Motor Skills on Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity in Children with Intellectual Disabilities: Difference in Severity. China Sport Science and Technology. 2023, 59, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vuijk, P.J.; Hartman, E.; Scherder, E.; Visscher, C. Motor performance of children with mild intellectual disability and borderline intellectual functioning. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marieke, W.; Suzanne, H.; Esther, H.; Chris, V. Are gross motor skills and sports participation related in children with intellectual disabilities? Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011, 32, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, E.; Houwen, S.; Scherder, E.; Visscher, C. On the relationship between motor performance and executive functioning in children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguia, K.F.; Capio, C.M.; Simons, J. Object control skills influence the physical activity of children with intellectual disability in a developing country: The Philippines. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonis, K.P.; Jernice, T.S.Y. The gross motor skills of children with mild learning disabilities. International Journal of Special Education 2014, 29. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, 2013; pp. 936–937. [Google Scholar]

- Alesi, M.; Battaglia, G.; Pepi, A.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A. Gross motor proficiency and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with Down syndrome, children with borderline intellectual functioning, and typically developing children. Medicine. 2018, 97, e12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.C. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1994, 272, 828–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, S.; Jansen, D.E.M.C.; Vogels, A.G.C.; Reijneveld, S.A. Mental health problems in children with intellectual disability: use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 52, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovgan, K.; Mazurek, M.O.; Hansen, J. Measurement invariance of the child behavior checklist in children with autism spectrum disorder with and without intellectual disability: Follow-up study. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 58, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostikj-Ivanovikj, V. Behavioral Problems In Children With Mild And Moderate Intellectual Disability. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadini, T.; Courbois, Y.; Gentaz, E. Eye-tracking-based experimental paradigm to assess social-emotional abilities in young individuals with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0266176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.J.; Faraone, S.V.; Leon, T.L.; Biederman, J.; Spencer, T.J.; Adler, L.A. The Relationship Between Executive Function Deficits and DSM-5-Defined ADHD Symptoms. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Wang, Y. A survey of children's behavioral problems and Sensory processing disorders in urban areas of Beijing. Chinese Mental Health Journal 1997, 11, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, P.; Vajdic, C.; Trollor, J.; Reppermund, S. Prevalence and incidence of physical health conditions in people with intellectual disability – a systematic review. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0256294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, A. Jensory integration and learning disorders; Western Psychological Services: Los Angels, 1972; Volume 36, pp. 258–259. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.A.; Hastings, R.P.; Totsika, V. Clinical utility of the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a screen for emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents with intellectual disability. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2020, 218, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.A. Test of Gross Motor Development (Second Edition) Examiner’s Manual; pro-ed Publishers: Austin, TX, 2000; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Taylor and Francis, 2013; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lixia, Q.; Xiaoying, J. An Investigation Report on Current Situation of the Development of Mainstreaming in China. Chinese Journal of Special Education. 2004, (05), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Z.; Dandan, W.; Xueping, W. Characteristics and Differences of Fundamental Movement Skills in Children and Youth with Different Severity of Intellectual Disability. Journal of Capital University of Physical Education and Sports. 2022, 34(02), 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chunling, L.; Hongying, M. Development and education of children with intellectual disabilities; Peking University Press: Beijing, 2011; pp. 26-28, 68-72. [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung, B. Motor proficiency differences among students with intellectual disabilities, autism, and developmental disability. J. Exerc. Rehabilitation 2018, 14, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilker, Y.; Nevin, E.; Ferman, K.; Bulent, A.; Erdal, Z.; Zafer, C. The Effects of Water Exercises and Swimming on Physical Fitness of Children with Mental Retardation. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2009, 21, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Nianli, Z. Development and education of children with autism spectrum disorders; Peking University Press: Beijing, 2011; pp. 10-13, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D.; Charman, T.; Pickles, A.; Chandler, S.; Loucas, T.; Simonoff, E.; Baird, G. Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, M.C.; Koot, H.M. DSM-IV Disorders in Children With Borderline to Moderate Intellectual Disability. I: Prevalence and Impact. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, Z.; Junming, F. The Medical Foundation of Special Education; Peking University Press: Beijing, 2011; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).