1. Introduction

Personality is defined as characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours over time and across situations [

1]. The Big Five personality traits represent the most widely accepted and commonly used taxonomy of personality [

2]. This model defines personality based on five dimensions: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

A limitation of the existing literature on personality and stress and coping strategies is its analysis of individual personality traits in isolation, without any considerations of how these operate together [

3]. In other words, the effect of high and low scores for single traits (e.g., extraversion or neuroticism) is prioritised, creating to a variable-centred approach, rather than assessing high-low combinations of different traits simultaneously (e.g., high extraversion, low neuroticism) in a person-centred approach [

4]. Personality psychology has traditionally focused on the variable-centred approach, which looks at individual differences and their observable variations in different personality traits. However, this may overlook one essential aspect of personality: the way in which traits are configured within an individual. For example, an individual is not exclusively extraverted, conscientious, or neurotic, but rather a combination of these traits. The score of any single trait may strengthen or weaken the relationship between another one [

5,

6].

Thus, one of the motivating assumptions of the person-centred approach is the idea that traits should not be studied in isolation. The person-centred approach identifies groups of individuals who share particular or similarly connected attributes. In the field of personality, the person-centred approach identifies individuals with the same basic personality profile [

7]. Personality types describe personality by assessing an individual’s scores on several personality dimensions. Nowadays there is little evidence for discrete personality types. Torgersen [

8] explored eight personality types based on different high vs. low combinations of the hysterical (extraversion), oral (neuroticism) and obsessive (conscientiousness). Vollrath and Torgersen [

6] replicated these eight personality types (see

Table 1 for the composition of the types and their labels), which may serve as useful and convenient labels for trait combinations associated with consequential outcomes. Therefore, a replicable and empirically validated personality typology can play an important and even necessary role in research on personality development [

9].

The Big Five model has contributed significantly to understanding dispositional coping. Lazarus & Folkman [

10] described coping as cognitive and behavioural reactions employed to deal with stressful demands perceived of as exceeding one’s personal resources. Tobin et al. [

11] determined that coping could be organised into two general categories; “coping activities that engage the individual with, and coping activities that disengage the individual from, the stressful situation” (p. 355). The authors differentiated between four specific engaged coping strategies: problem solving, cognitive restructuring, social support, and emotional expression. They noted that four specific disengaged coping strategies could also be employed: problem avoidance, wishful thinking, self-criticism, and social withdrawal. Likewise, engaged coping strategies have been treated as adaptive coping, while avoidance (disengaged) coping strategies are viewed as forms of maladaptive coping [

1,

12,

13].

Most research has focused on the role personality plays in coping, particularly traits like neuroticism and extraversion, while other personality dimensions have received relatively less attention [

14]. Studies have found that individuals with high neuroticism experience more stressful events and use passive and maladaptive coping, such as ignoring the problem, distracting, venting, or avoiding. Meanwhile, individuals with higher extraversion use more active coping strategies and seek more social support. However, regarding other personality dimensions, openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to active and less evasive coping [

15].

In the extensive literature on academic stress in university students [

16,

17,

18], alarming trends have recently been detected in perceived stress in this community. University students are exposed to a wide range of potentially stressful situations which can negatively affect their academic achievement and health [

19]. In fact, high stress levels experienced by university students are considered one of the more prevalent psychosocial problems in the university community. In their daily lives, university students must manage a wide variety of demands both academic and non-academic [

20]. Therefore, the university is a stressful time for most students. According to Russell & Petrie [

21], a student’s ability to adapt to university stress depends on three factors: academic performance, social adjustment, and personal adjustment. Yet little is known about how personality types relate to stress and coping, particularly among a student university sample. Only one study has examined how personality types compare in terms of the experience of stress and emotions and coping strategies in a sample of university students [

6]. The authors found that the most favourable stress and coping profile corresponded to personality types with low neuroticism and high conscientiousness, whereas those in which high neuroticism combined with low conscientiousness showed high vulnerability to stress and poor coping. Furthermore, the authors noted that the effects of extraversion were more ambiguous and appeared to depend on the specific combinations of neuroticism and conscientiousness. However, after several decades of studies on the impact of stress and coping strategies, substantial gaps and inconsistencies remain [

1].

Secondly, the literature reiterates the importance of considering both coping strategies and perceived coping efficacy in protection against stress [

19]. Though stress coping skills and perceived coping efficacy are two different concepts, they are related. Perceived coping efficacy could be considered a specific component of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy has been described as the belief in one’s capability to produce designated levels of performance for events that affect one’s life, “an important factor in determining how people feel, think, motivate themselves and behave” [

22]. Self-efficacy seems to strongly influence university adjustment [

22,

23], since individuals with a high sense of self-efficacy tend to feel able to overcome situational difficulties, attributing little stress to them. Different studies have found an association between the perception of self-efficacy and the coping strategies university students employ [

19,

24]. Coping strategies such as problem solving, positive re-evaluation and the search for social support have a positive effect on self-efficacy; however, other coping strategies such as venting negative emotions and negative auto-focus have a detrimental effect [

24].

Finally, gender is an essential variable in the relationship between university students and stress. Previous research has noted gender differences in stress levels and coping strategies [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Though women report higher stress levels than men [

25] they also make better use of emotional support [

28,

29]. Men, in contrast, tend more toward avoidance-focused coping [

26] and problem-focused coping than women [

28].

To date, no study has investigated the association between personality types, coping strategies, and perceived coping efficacy among university students. A better understanding of how these variables relate would have implications in the fields of education and clinical psychology. The use of adaptative coping strategies combined with a high level of perceived coping efficacy could result in greater wellbeing, quality of life, adaptation, or adjustment at university. Considering these gaps in the literature, the main aim of the present study was to explore the associations of eight personality types based on Torgersen’s typology with academic stress, coping strategies and perceived coping efficacy in a large sample of university students. Second, we explored the gender distribution of personality types and coping strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Data was collected from 1,305 psychology students at the University of Seville (Spain) who voluntarily participated. After the personality types analysis, the final sample included 810 participants, including 643 women (79.4%) and 167 men (20%); the average age was roughly 20 (M = 20.24; SD = 3.59).

2.2. Measures

Personality was assessed using the Spanish version of the Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) [

2,

30]. The NEO-FFI is a short self-report inventory that can be completed in approximately 15 minutes and measures the five personality dimensions described by Costa and McCrae: extraversion, degree of sociability, positive emotionality and general activity (e.g., I enjoy talking to people); agreeableness, altruistic, sympathetic and cooperative tendencies (e.g., I tend to think the best of people); conscientiousness, one’s level of self-control in planning and organisation (e.g., I work hard to achieve my goals); neuroticism, the tendency to experience negative emotions and psychological distress in response to stressors (e.g., when I'm under heavy stress, I sometimes feel like I'm going to fall apart); and openness to experience, levels of curiosity, independent judgment and conservativeness (e.g., I have a wide variety of intellectual interests). It is comprised of 60 items (12 per domain) rated on a 5-point Likert scale by indicating to what extent the respondents agree with each of the statements regarding themselves (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = neither agree nor disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree). Scores for each domain are the sum of the responses to the 12 items. The NEO-FFI has shown adequate levels of validity and reliability across a range of diverse populations. This Spanish version has appropriate indices of reliability and validity. Each of the five domains has been found to possess adequate internal consistency (α = 0.71 to 0.82) [

30] (see

Table S1 in the supplementary material for more details about the reliability of the scale).

Coping was assessed with the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI) originally created by Tobin et al. [

11] and adapted to Spanish by Cano-García et al. [

31]. This instrument contains a blank space for the respondent to describe a stressful situation in the maximum amount of detail. This is followed by the 40 items of the instrument, which reflect the thoughts, attitudes, feelings and coping behaviours linked to the situation described and scored on a Likert-type 5-point scale, where 0 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree. The instrument is composed of eight subscales, each with five items, so the range of direct scores for each is from 0 to 20. High scores indicate a major use of these strategies when faced with different stressful situations. The subscales are the following: problem solving (PS), understood as cognitive and behavioural strategies aimed at eliminating stress by modifying the situation which produces it (e.g., “I tried hard to resolve the problem”); cognitive restructuring (CR), understood as cognitive strategies that modify the meaning of the stressful situation (e.g., “I convinced myself that things were not as bad as they seemed”); social support (SS): understood as strategies referring to the search for emotional support (e.g., “I found somebody who was a good listener”); emotional expression (EE), defined as strategies aimed at releasing the emotions that arise during the stressful process (e.g., “I analyse my feelings and just let them out”); problem avoidance (PA), understood as strategies that include denial and avoidance of thoughts or acts related to the stressful event (e.g., “I refused to think about it too much”); wishful thinking (WT), understood as cognitive strategies that reflect the wish that reality were not stressful (e.g., “I wished I could have changed what had happened”); social withdrawal (SW), defined as strategies to withdraw from friends, family, peers and significant others associated with the emotional reaction to the stressful process (e.g., “I spent some time by myself”); and self-criticism (SC), understood as strategies based on self-blame and self-criticism due to the occurrence or inadequate handling of the stressful situation (e.g., “It was my mistake, so I have to suffer the consequences”).

Finally, in order to explore the perceived coping efficacy, one addition item is included (“I believe I can cope with the situation”). The variance and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the eight primary coping strategy ranged from 0.63 and 0.89 [

31], revealing good psychometric properties with Spanish samples. In the current study, the reliability indices for each coping strategy showed acceptable to excellent internal consistency in our sample, ranging from α = 0.71 for the problem avoidance strategy to α = 0.91 for the strategy of self-criticism (see

Table S1 in the supplementary material for more details about the reliability of the scale).

2.3. Procedure

In the first semester of each academic year from 2010-2011 through 2021-2022, students in the Personality Psychology and Human Diversity, in the second year of the Psychology degree program at the University of Seville (Spain), completed a battery of instruments, including the CSI and the NEO-FFI. The work was done on campus anonymously under the supervision of teaching staff. The stressful situation to be addressed in the CSI was academic; specifically, students had to describe a stressful academic situation they experienced during their university studies. They then respond to the 40 items of the inventory, plus the item related to perceived coping efficacy.

In order to create the personality type variable, scores for neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness were changed to an ordinal variable and assigned a value of high, medium or low. Subjects with medium scores were excluded and the rest assessed according to Torgersen’s classification of eight personality types (1995) (See

Table 1). However, instead of using the medians to determine the score levels, as those authors did, we transformed the NEO-FFI dimensions using the T-scores from a scale that relied on a large normative Spanish sample (Manga et al., 2004) in which T-scores means = 50 were considered for each dimension. We classified the participants of our study in low, medium, or high scores following a statistical scoring criterion with ±0.5 standard deviations from the normative group mean.

The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent is obtained in writing from each participant. Data processing has complied with the current regulations in this regard: first, with the Spanish Personal Data Protection Act of 1999 and, second, with the Spanish Data Protection Rule (GDPR) of 2016, which guarantees the anonymity and security of the information at all times As the subjects were university students, the following requirements were established: all were recruited by faculty members with whom they have had no academic involvement; the activity was voluntary, without incentives of any kind; and the activity was done outside of class.

2.4. Data Analyses

First, the differences in the eight coping dimensions were contrasted in a two-way MANOVA with gender and personality types as independent variables. Beforehand, the assumption of multivariate normality was evaluated with Mahalanobis distances and Mardia’s test; homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrices was assessed using Box’s M test; and the homoscedasticity for each coping strategy was measured with Levene’s tests. Because of the unbalanced design, and the lack of normality and homoscedasticity, Wilks’ Lambda was chosen as the contrast statistic [

32].

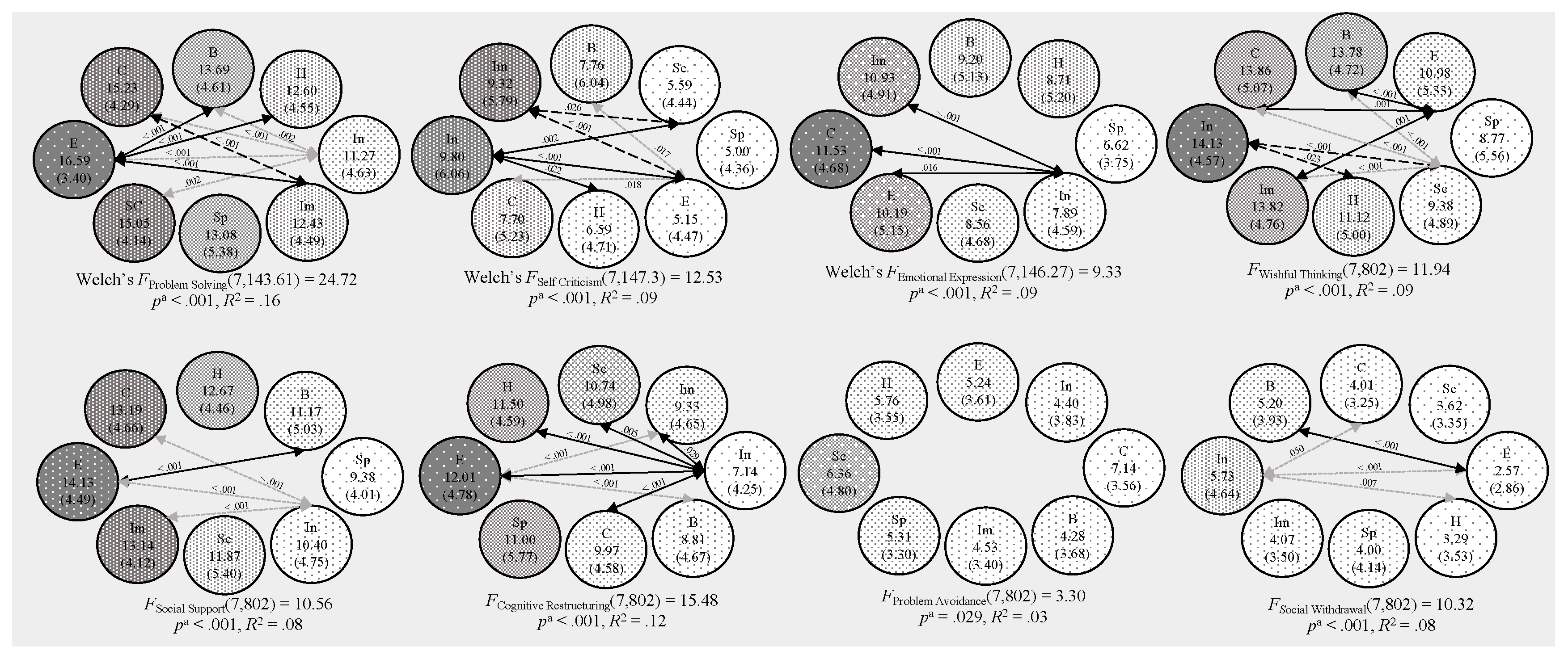

Because no interaction was detected and some of the coping strategies revealed heteroscedasticity, the MANOVA was followed by 16 one-way ANOVA tests, eight with gender as a factor and eight with personality types as a factor. This was to run Welch’s test and Games-Howell when homoscedasticity was not met, which is not possible in factorial ANOVA. Adjusted probabilities (adjusted p = p * 16) were used in all the ANOVA tests. The R2 of each factor was used as the effect size index, considering a medium effect size for values of 0.06 or a large effect size for 0.14. When statistical differences were found, multiple comparison tests, Tukey or Games-Horwell was run depending on homoscedasticity, with an additional Bonferroni adjustment for 16 tests.

Finally, a one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc comparisons were done to analyse the relationships between personality types and self-perceived efficacy, using Welch’s F and the Games-Howell test because of the heteroscedasticity. Again, R2 was used as the effect-size index.

The software SPSS 26.0 was used for the MANOVA and ANOVA plus post-hoc multiple comparisons; JASP 0.16 was used for reliability and Mardia’s tests.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between personality types and (i) the coping strategies and (ii) perceived coping efficacy among a large sample of university students using a person-centred approach. The study also explored the distribution of gender in both the personality types and coping strategies.

Along with previous personality types proposed study by Vollrath and Torgersen [

6], the most representative types in our sample were the insecure (21.7%), the entrepreneur (17.9%) and the brooder (17.8%), and the less representative types were the spectator (1.6%) and the sceptic (4.8%). However, the distribution of the impulsive, complicated and hedonist types were different between the two studies. Regarding gender, the types most prevalent among women were the insecure (20.8%) and the brooder type (19%) as also found by Vollrath and Torgersen [

6]. However, while the most representative types among men in this study were the insecure (25.1%), and the entrepreneur (15.6%), the hedonist and insecure types were most prevalent in the Vollrath and Torgersen [

6] sample. In both studies, the most representative types for women were similar and women were over-represented [

6]. It is worth highlighting that the current study focused exclusively on psychology students. In contrast, the earlier study included a cohort of students working toward different degrees. The method for creating the types was different between the two studies. In the Vollrath and Torgersen study [

6], each participant was assigned to one of the eight personality types by splitting the scales at the median and combining high and low scores. However, our personality types were created according to the mean T-score obtained in each dimension of the NEO-FFI, following the statistical criteria of scores 0.5 SD above and/or below the normative group mean.

Personality may explain why some people are more vulnerable to stress than others [

1] and may influence the reactivity to the stressor, thus affecting the choice of coping strategies, the degree of effectiveness of the chosen coping strategy, or both [

33]. The current findings indicate distinct coping strategies among different personality types. Specifically, we found two contrasting profiles in terms of vulnerability to stress and the use of adaptative coping strategies: the insecure and the entrepreneur types.

The insecure type was characterised by a high vulnerability with poor coping since it combines high neuroticism with low conscientiousness and low extraversion. These individuals presented high scores in wishful thinking, social withdrawal, and self-criticism, all of which are considered dysfunctional coping strategies; similarly, they had low scores for problem solving, cognitive restructuring, emotional expression and social support (functional coping strategies). In contrast, the entrepreneur was characterised by a low vulnerability to stress since this personality type combines low neuroticism with high conscientiousness and high extraversion. These individuals presented high scores in adaptive coping strategies such as problem solving, cognitive restructuring, emotional expression and social support; and low scores in dysfunctional coping such as wishful thinking, social withdrawal and self-criticism.

Our results align with the previous study [

6], which found that individuals with high neuroticism and conscientiousness—the impulsive and especially insecure types—used maladaptive coping strategies. This could indicate that students with an impulsive and, more significantly, insecure personality type are more vulnerable to stress. In contrast, personality types with low neuroticism with high conscientiousness, particularly the entrepreneur, opted for adaptive coping strategies. Thus, our findings reinforce the importance of personality and coping in student stress as noted in previous studies [

34,

35]. Students with an entrepreneur personality type could choose the right coping strategies and use them effectively to reduce stress experienced in academic situations. Some researchers found that coping strategies allowed students to change the course of things, develop more adaptive behaviours, possibly expand on their academic achievements [

36,

37] and experience fewer symptoms of depression [

38,

39]. In contrast, the use of maladaptive coping strategies such as wishful thinking and self-criticism, mainly by the insecure and impulsive types, is a serious problem since there is a negative association between the use of maladaptive coping strategies and academic performance [

40] and mental and physical health [

41].

In terms of gender differences in the coping strategies (regardless of the personality types later assigned), our results were like those obtained in other recent investigations, which found significant differences between women and men. Specifically, women are more likely to use verbal coping strategies such as seeking social support, emotional expression, wishful thinking or internal language [

27,

29]. However, this result must be interpreted with caution, since among all the coping strategies mentioned, only the relationship between emotional expression and gender obtained a medium effect. Furthermore, it is important to bear in mind that the gender differences in coping behaviour are likely due to gender socialisation as opposed to inherent differences in coping behaviours of men and women [

28].

Regarding the relationship between personality and perceived coping efficacy, our findings shed more light on this issue. According to our results, personality types characterised by low neuroticism with high conscientiousness—like the entrepreneur and the sceptic—exhibited higher perceived coping efficacy than those with a high score in neuroticism. It is interesting to note that the role of extraversion in perceived coping efficacy did not seem to have much of an effect. The entrepreneur and sceptic personality types were similar regarding the high level of their perceived coping efficacy, with the entrepreneur showing high extraversion and the sceptic, low extraversion. Stress coping skills and perceived coping efficacy may be two different concepts, but they are related. Students who cannot resolve a series of problems associated with their university experience can suffer mental stress and frustration associated with academic failure [

42]. For instance, if students characterised as insecure are involved in a stressful task, they may not believe they are up to it, leading them to use maladaptive coping strategies [

22] and making them vulnerable to chronic stress. Therefore, a better understanding of how individuals with different personality types manage stress, specifically academic stress, could prove invaluable for intervention and prevention efforts designed to enhance academic achievement and bolster psychological wellbeing and health. Overall, and in accordance with Vollrath and Torgersen [

6] our findings suggest that this typology helps address the question as to how individuals with different combinations of personality traits manage stressful situations and their perception of the resources, they have to cope with them.

The main strength of this study includes the analysis of the typological personality approach in a large university sample, using a standard and validated measure of personality traits and coping strategies. However, the study has some limitations. First, the results cannot be generalised to the general population or students from other schools and universities since all participants were recruited from the same university, specifically from the School of Psychology. Therefore, futures studies are needed with samples more diverse in terms of age, region and culture. Second, the study design did not enable causal inferences to be made about coping strategies, perceived coping efficacy and personality types, nor did it provide insight into how personality types evolve over time. Therefore, further prospective longitudinal studies are needed. Third, this studied relied on a single CSI item to measure perceived coping efficacy. Since this was considered an important variable in controlling stress and is a protective factor against the impact of day-to-day stressors, it should ideally be measured with a specific instrument.

Future studies should examine other characteristics that may influence the relationship between personality types, coping strategies and perceived coping efficacy in the university context such as prior academic performance and self-regulation; motivation could also be of interest. Although there is no consensus on the optimal way to determine personality type [

9], further studies with more advanced statistical techniques are needed for a definitive scoring process of the eight personality types. The CSI instrument assesses coping strategies used to manage or tolerate stressful situations; the current study has focused only on one type of stressful situation, e.g., academic stress. Students may cope with academic stress differently than they would with other life stressors. Therefore, future studies are necessary to analyse whether the relationship between personality types and coping strategies differ from one stressful situation to the next, as well as longitudinal studies to find out if this relationship remains stable over time or changes as people age. In addition, further research is needed to clarify how gender relates to coping strategies.