1. Introduction

Childhood obesity has been cited as an epidemic, and one of the most prevalent public health challenges in the United States [

1]. In the 1970s, rates of childhood obesity were 5%; by 2008, the United States had reached a rate of 17% [

2], more than tripling the prevalence in 40 years [

3]. Currently, the overall rates of childhood obesity are rising at a slower rate; however, rates of childhood obesity in underserved neighborhoods are increasing at a faster pace [

4]. To respond to this concerning trend, resources from federal, state, and local health departments along with non-profit health organizations have focused on a myriad of solutions with schools being at the epicenter where children spend much of their day and consume breakfast, lunch, and snacks.

School districts have implemented school-wide wellness policies, have improved school food to meet the national regulations of Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act [

5], and implemented garden-to-cafeteria programs. The policy, systems-level and environmental changes may be linked to declining obesity rates [

6,

7,

8]; however, often left out of this approach are the permanent residents of the schools, teachers. Teachers understand that healthy students are better learners [

9]. The inclusion of teachers in identifying multi-component solutions as well as integrating them into the program delivery to address childhood obesity and support child health broadly can be advantageous. Essential to this collaborative approach are authentic partnerships with educators and schools that center their voices and perspectives as the stakeholders closest to the community who will be served [

10,

11].

Teachers impact the lives of students they teach. Unfortunately, due in part to the nature of demands within schools and classrooms, it is a challenge to prioritize the health of these professionals. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the urgency for school districts to attend to the health and well-being of teachers as 55% of teachers report thinking about or planning to leave the profession [

12]. A recent 2022 RAND report found that nearly twice as many teachers reported job-related stress compared with the general population. The researchers also conclude that employer-provided wellness programming was associated with lower levels of job-related stress for teachers [

13].

Any new initiative, whether a program or policy, requires teachers’ buy in for the action to reach its intended effect. Thus, teachers who are equipped and confident in translating knowledge into daily lessons play an essential role in advancing childhood obesity and child health efforts. A multicomponent approach that centers teachers’ health and well-being is a starting place to address childhood obesity at the school-level. By engaging teachers with health-promoting activities and supporting healthy habits as part of their school day, teachers have an opportunity to reinforce self-care and become role models to their students [

14]. In so doing, teachers are then well positioned to transfer the knowledge and skills of personal health and wellbeing to the students in their classrooms, paving the way for this information to be applied to their lives for benefit across the lifespan. As collaborative champions, teachers best know their students, school culture, and community strengths. They are the foundation upon which school health is built and are the front door that welcomes students to develop healthy habits. Investing in teacher well-being is a short and long-term investment in creating a culture of health and learning.

Teacher well-being can be defined by a range of objective and subjective psychological, physical, and social factors that encompass health, resilience, and self-efficacy [

15]. Interventions to improve teacher well-being include programming to support mindfulness [

16], engagement and social connections [

17]. Previous studies have found when teachers engage in a commitment to their own health (physical and mental), students benefit from formal and informal instruction [

18,

19]. These positive outcomes move beyond academic productivity toward a holistic approach to both student well-being and professional autonomy for educators.

2. Materials and Methods

In Washington, DC, the City Council took a bold step to pass the Healthy Schools Act of 2010 (most recently amended by the Healthy Students Amendment Act 2018) which established comprehensive requirements to improve school meal and nutrition standards in the cafeteria and vending machines, increase student physical activity and health education time, support school gardens and farm-to-school education, and establish local school wellness policies to specifically address obesity and hunger [

20]. This environment created an opportunity for the implementation of a teacher-led program in elementary schools to address childhood obesity.

Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 is a five-year multicomponent intervention funded by USDA’s National Institute on Food and Agriculture that began in 2017. The goal of this quasi-experimental prospective study is to engage teachers to teach nutrition literacy skills and knowledge to prevent obesity among elementary school students in Washington, DC. In developing a multi-level equity focused approach, the program team utilized both the Social Ecological Model [

21] and Kumanyika’s Getting to Equity (GTE) in obesity prevention framework [

22] to improve student and teacher health. Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 aligns with the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) [

23] premise that introducing healthy behaviors during childhood is more effective than trying to change unhealthy behaviors during adulthood [

24] and the established correlation that healthy students are better learners [

25,

26]. The study design and student nutrition literacy instrument validation have been described previously [

27,

28]. Approval for this study was granted by the University’s Institutional Review Board in July 2017. Written informed consent was provided by teachers and student prior to data collection activities.

2.1. Priority Audience

One hundred percent of students in the two intervention and two comparison schools are in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and eligible for free breakfast and lunch. School enrollment ranged from 300-500 students in grades 1-5th. Students attending the schools are 90-98% Black and 2-10% Hispanic/Latino. Across all four schools, 2018-19 standardized tests show that 10-24% of students tested met or exceeded expectations in Math and 8-12% of students tested met or exceeded expectations in English Language Arts. Among teachers, demographic assessments were similar between the intervention and comparison schools. The majority of teachers at partner schools identified as Black (66%) and female (85%) with a mean age of 36 years, which is demographically representative of teachers in the Washington DC region. 38% of teachers had been teaching less than five years and 62% had been teaching five years or more.

Surveys were administered to participating teachers two times at baseline (n=92) and post-intervention (n=92). The Teacher Health Survey (THS) includes questions regarding personal health habits, mental health, job stress, beliefs about health and education, and self-efficacy. Responses are recorded on a Likert scale

negatively (1) to

positively (5) to self-report agreement/disagreement regarding each item. Teachers also provide demographic information including their gender, age, race/ethnicity, and teaching role (e.g., general classroom teachers, special education teachers). An aggregate health score was computed (range of 0-120) which included the sum of several variables: self-reported overall health, chronic condition (diabetes, asthma, and/or high blood pressure), health education beliefs (8 items), and self-efficacy (5 items). The THS has been previously administered in a similar setting and demonstrates good psychometric properties [

9].

2.2. Research Design

The primary research arm of this study focused on the professional development sessions with teachers to equip them with the skills and knowledge to incorporate nutrition into their classroom lessons. The overarching goal was to empower teachers with strategies for integrating health into their own lives and in the classroom curriculum. The program sessions were designed collaboratively with teachers. Each of the five professional development sessions started with a teacher wellbeing component, such as healthful eating, mindfulness, or a physical activity break. This simple start was intentional and acknowledged their own well-being is important and valued. After the wellness activity, the project team then presented a pre-developed curriculum from the USDA’s Serving up MyPlate: A Yummy Curriculum. This curriculum was selected because it aligns with core subject standards and therefore teachers could incorporate food and nutrition knowledge while implementing a math, science, or English Language lesson. Teachers were invited to attend the sessions by the school principal, who also attended and demonstrated leadership support for the wellness program. Each teacher was also provided with a complete kit that included paper copies of lesson materials, information from the professional development modules, and all other necessary supplies such as crayons, pencils, scissors, and stickers to deliver lessons. Pre and post surveys were administered to students to assess nutrition knowledge and attitudes [see also 27-28].

2.3. Lesson Implementation

Participating teachers in intervention schools were asked to implement a minimum of three nutrition lessons over the course of the school year and to log the implementation of each lesson in an online Qualtrics form. Teachers could also provide feedback on the lessons and curriculum in the form. Student knowledge was assessed via the validated Student Nutrition Literacy Survey consisting of 18 items assessing nutrition knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and intent [

29].

3. Results

Analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 29 and

R Core Team (2021) tidyverse package [

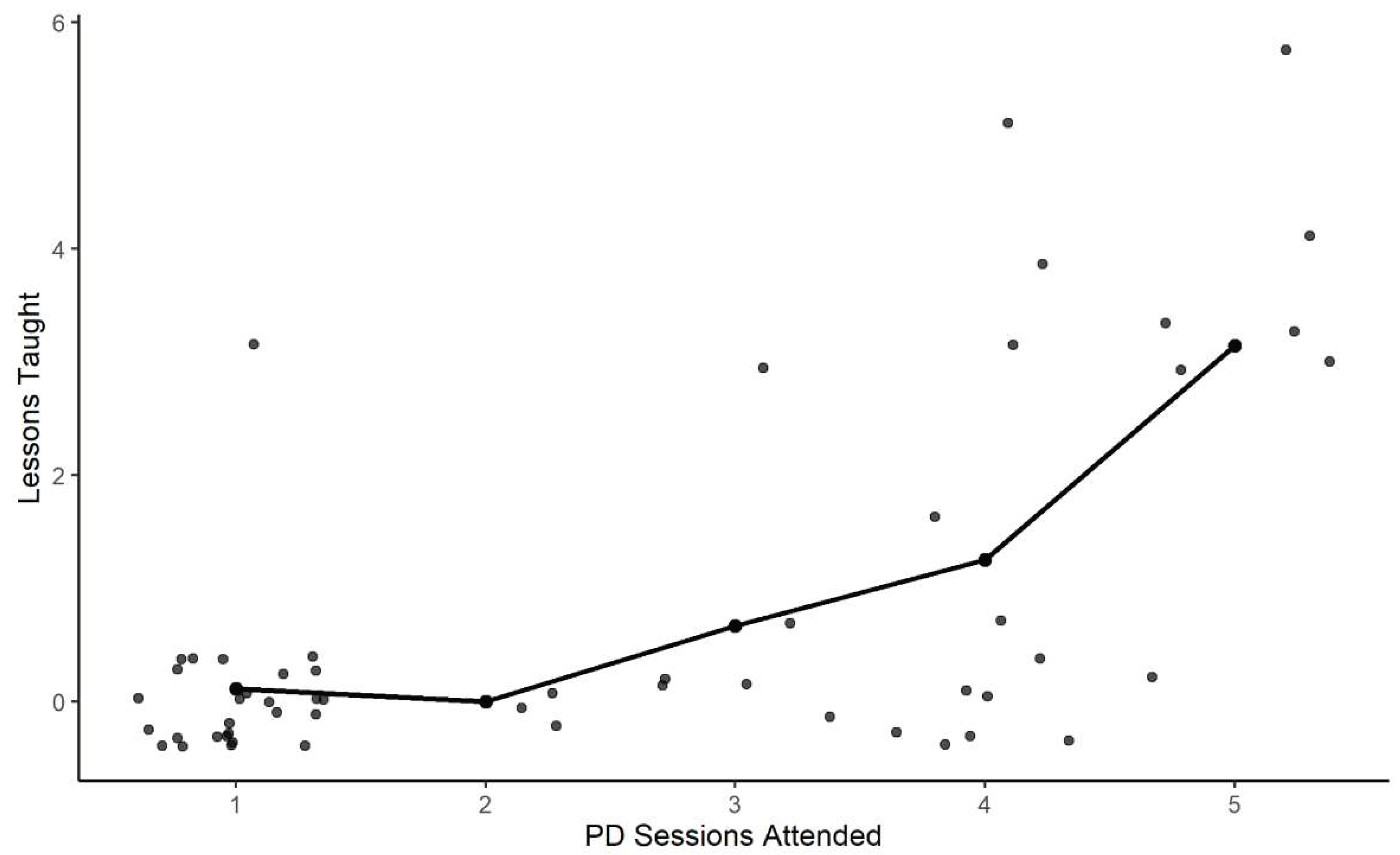

30]. Descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize teacher sociodemographic characteristics. Ninety-two teachers completed the THS pre and post surveys. Fifty-five teachers participated in one or more professional development sessions in the intervention schools; on average, teachers attended four of the five (SD = 1.5) professional development sessions. Teachers implemented a total of 71 nutrition lessons. Among teachers who implemented lessons, the average number of lessons implemented was four, with a range of one to nine lessons. There was a significant positive correlation between the number of professional development sessions attended and the number of nutrition lessons implemented in the classroom among teachers in intervention schools (

Figure 1) (r = 0.54, p<0.01, n=55) [

28].

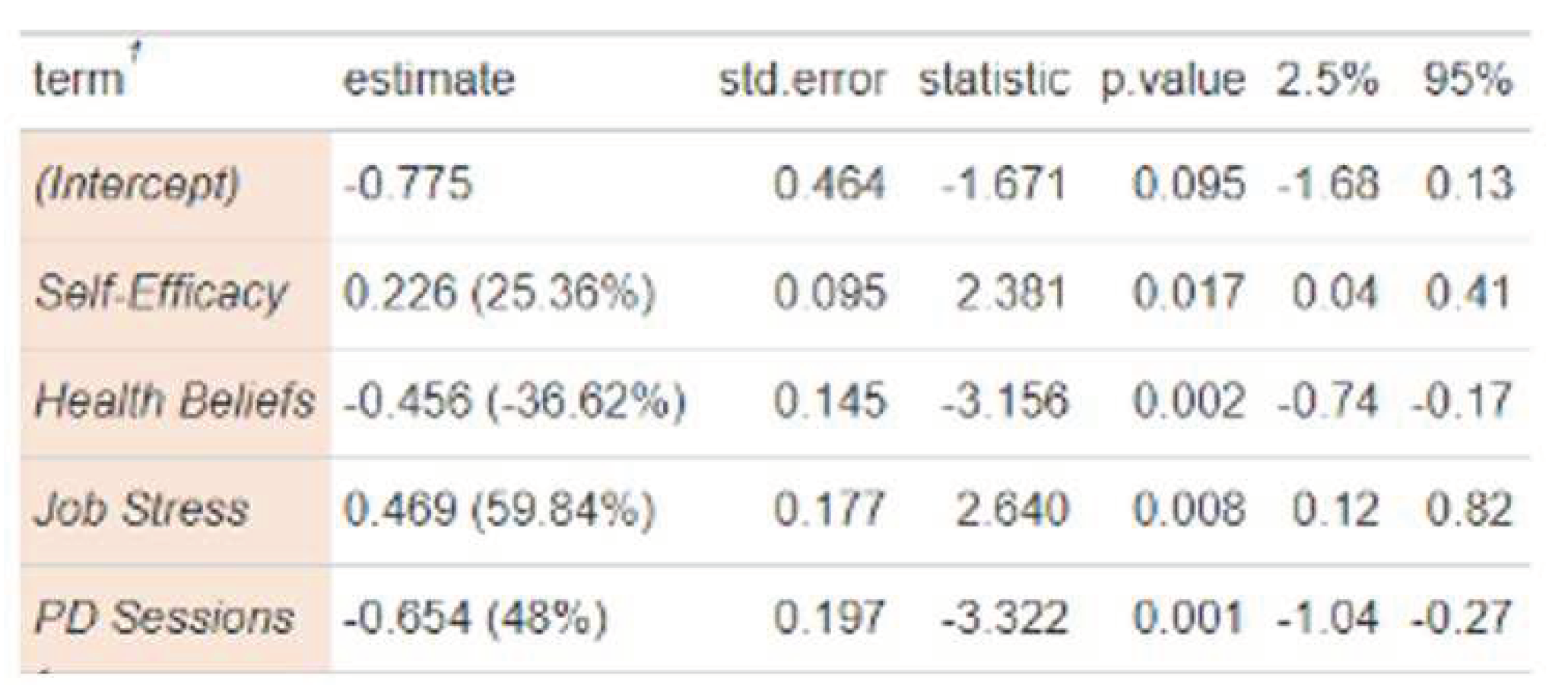

At baseline assessment, there were no differences among teacher average cumulative health scores by length of teaching time, grade taught, age or gender. Regression analysis demonstrated that self-efficacy, job stress, and professional development attendance predicted nutrition lesson implementation (

Table 1).

Each additional professional development session attended was associated with a 48% increase in likelihood to implement nutrition lessons in the classroom. Each additional increase in self-efficacy score was associated with a 25% increase in likelihood to implement nutrition lessons.

There was also a significant association between stress levels, cumulative health scores and lesson implementation. Of note, over 80% of teachers reported feeling ‘very high’ or ‘high’ stress in general. Further, stress scores were inversely correlated with lesson implementation (r = 0.46; p < 0.01); teachers who reported lower stress were significantly more likely to implement nutrition lessons than teachers who reported high stress (p <0.01). Teachers who attended 1 or more professional development sessions reported lower stress scores (mean score 2.2) compared to teachers who did not attend professional development sessions (mean score 3.8) (t=2.41, df=17, p<0.05). Teachers who did not implement nutrition lessons had an average overall health score of 63, whereas teachers who implemented 3 or more lessons, had an average overall health score of 86. Previous research had demonstrated that teachers who work in urban settings consistently report higher stress than those in rural or suburban settings [

31].

Students who received lessons from teachers who participated in the professional development program advanced their own nutrition knowledge. Participating students in grades 1-5 completed the brief student nutrition literacy survey at baseline (n=1001) and post assessment. There were no significant differences between student pre-test knowledge scores between intervention and comparison schools. There was a significant increase in student knowledge scores among students in the intervention schools (p = < 0.01, n= 659) compared to students in the comparison schools. Students who received the intervention (3 or more lessons) had knowledge scores that were on average 10% higher than those fewer lessons (0-2 lessons received) (p < .001, df = 2, F = 9.66). Students who received more than 3 lessons had scores that were 8% higher on average than those who received fewer lessons (0-2) (p < .01) [

28].

3.1. Limitations

There are important limitations to consider. The professional development program was opt-in introducing a healthy worker selection bias, and not all participating teachers completed the THS at each assessment time. Students may have received nutrition and health information from other sources that was not assessed. Generalizability is limited by the small sample size and number of schools. Further, the urban geographic region is not generalizable to other school districts.

4. Discussion

The preliminary findings emphasize the beneficial role of professional development, health beliefs, and teacher self-efficacy. These results indicate that a short-term professional development program supporting teacher health and integrating nutrition education into core classroom subjects demonstrates feasibility and sustainability. The role of education in supporting behavior change, both for teachers and students, is underscored in the preliminary findings from Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0. This study sought to test the effects of a teacher-led childhood obesity program in the school setting. Unique to this study was how teachers were engaged and empowered through the professional development program. As the leaders of their classrooms, they contribute to creating a culture of health in their classrooms that may influence the larger school environment and the surrounding community. Investing in teachers’ knowledge of nutrition education is a sustainable approach to support both teacher and student well-being. The social ecological model hinges upon the individual and interpersonal relationships that bind a culture and society and allow for systemic impact. Teachers are integral within the school system. Any program meant to advance student health that bypasses teachers reduces the likelihood for long-term success and scale [

32].

These findings are consistent with the principles of the social ecological model which emphasizes the multiple spheres of influence that are mutually reinforcing; in this intervention study, the impact of teachers’ knowledge, engagement with professional development, and implementation of nutrition lessons equips teachers as agents of change. This builds on previous research that posits teachers offer a critical role in student motivation and engagement [

33].

Teachers are an untapped resource in the childhood obesity crisis and their leadership is vital. To be effective, efforts to advance student health must begin with strategies to support teacher health. Building professional development into the workplace that address teacher health concerns must be prioritized. For these opportunities to be meaningful, they must be responsive and prioritize the unique needs of each school’s teachers. Thus, regular assessments of teacher health beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge are essential to understand changing needs. These assessments can then inform professional development offerings that are tailored to and co-created by teachers themselves. Explicit investment in teacher well-being is an investment in whole school health.

From a collaborative research standpoint, partnering with teachers builds capacity through empowerment while simultaneously supporting the social and economic resources of a community, two of the four key quadrants in Kumanyika’s GTE framework. Equipping teachers with the information, skills, and resources to manage their personal health allows them to become both the medium and the message in their classrooms. This poises teachers as agents of change who know the health needs, abilities, and opportunities of their students.

Activating teachers as assets in the fight against childhood obesity operationalizes efforts towards achieving health equity. Policies that require teacher well-being programs to be implemented may be a first step to advancing the Whole Child, Whole School, Whole Community framework. Further, professional development opportunities for teachers and designed collaboratively with teachers can translate policy mandates into effective strategies in the classroom. Teacher engagement is a vital component to support efforts to reduce the prevalence of childhood obesity.

4.1. Implications for Future Research

The holistic approach described in the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model illustrates a model for creating a culture of health in the school for teachers, staff, and students [

34]. Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 program centers teachers in a leadership role to support quality nutrition education for both teachers and students. The preliminary results of Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 further support the feasibility of professional development sessions on health-related content as a promising strategy to support both teaching well-being and obesity prevention efforts [

35]. Teachers play a powerful role in school-based obesity prevention efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and S.I.B; methodology, A.S, S.I.B., M.H.; formal analysis, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., R.M.; writing—review and editing, M.H. A.S.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, A.S, S.I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture from the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2017-68001-26356.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of American University (protocol code IRB-2018-67 and date of approval June 27, 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from teachers and parents of all students. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Data Availability Statement

Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 data is available upon request. The data presented in this study are available by request from the corresponding author. .

Acknowledgments

We thank the Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 Board of Advisors for their contributions: Donna Banzon, Caron Gremont, Robert Jaber, Nancy Katz, Miriam Kenyon, and Lindsay Palmer. A special thanks to the elementary school principals, teachers, and students in Washington, DC, for their participation, and Martha’s Table for their partnership.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the data collection, analyses, or in the interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kumar, S., & Kaufman, T. (2018). Childhood obesity. Panminerva Medica, 60(4). [CrossRef]

- Bryan, S., Afful, J., Carroll, M., et al. (2021). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [CrossRef]

- Harvard. (2016, April 8). Child obesity. Obesity Prevention Source. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends-original/global-obesity-trends-in-children/#:~:text=North%20America&text=In%20the%201970s%2C%205%20percent,19%20percent%20versus%2015%20percent.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2022, November 11). Ages 10-17. State of Childhood Obesity. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/demographic-data/ages-10-17/#:~:text=Roughly%20one%20in%20six%20youth,to%20the%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic.

-

S.3307 - Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 - congress. S.3307 - Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. (2010). Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3307.

- Ayala, G. X., Monge-Rojas, R., King, A. C., et al. (2021). The Social Environment and childhood obesity: Implications for research and practice in the United States and countries in Latin America. Obesity Reviews, 22(S3). [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, D. M., Ranjit, N., & Pérez, A. (2017). Surveillance systems to track and evaluate obesity prevention efforts. Annual Review of Public Health, 38(1), 187–214. [CrossRef]

- Holston, D., Stroope, J., Cater, M., et al. (2020). Implementing policy, systems, and environmental change through community coalitions and extension partnerships to address obesity in rural Louisiana. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. [CrossRef]

- Snelling, A., Ernst, J., & Belson, S. (2013). Teachers as role models in solving childhood obesity. Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 03(01), 055–060. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, E., Magarati, M., Boursaw, B., Oetzel, J., Devia, C., Ortiz, K., Wallerstein, N. (2020). Characteristics and Practices Within Research Partnerships for Health and Social Equity. Nurs Res. Jan/Feb;69(1):51-61. [CrossRef]

- Kumanyika, S.K. (2022) Advancing Health Equity Efforts to Reduce Obesity: Changing the Course. Annu Rev Nutr. 22;42:453-480. [CrossRef]

- Walker, T. (2022). Survey: Alarming number of educators may soon leave the profession. NEA. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/survey-alarming-number-educators-may-soon-leave-profession.

- Steiner, E. D., Doan, S., Woo, A., Gittens, A. D., Lawrence, R. A., Berdie, L., Wolfe, R. L., Greer, L., & Schwartz, H. L. (2022). Restoring Teacher and Principal Well-Being Is an Essential Step for Rebuilding Schools: Findings from the State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal Surveys. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-4.html.

- Pulimeno, M., Piscitelli, P., Colazzo, S., et al. (2020). School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(4), 316–324. [CrossRef]

- Dania, A. & Tannehill, D. (2022) Moving within learning communities as an act of performing professional wellbeing, Professional Development in Education. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. S., Bartlett, B., Greben, M., & Hand, K. (2017). A systematic review of mindfulness interventions for in-service teachers: A tool to enhance teacher wellbeing and performance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 26-42.

- Falecki, D., Mann, E. (2021). Practical Applications for Building Teacher WellBeing in Education. In: Mansfield, C.F. (eds) Cultivating Teacher Resilience. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Kalicki, M., Belson, S. I., McClave, R., & Snelling, A. (2019). Healthy Educators, Healthy Children: A Pathway to Lifelong Health Starts in Early Childhood. JOURNAL OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Snelling, A., Irvine Belson, S., & Young, J. (2011). School Health Reform: Investigating the Role of Teachers. Journal of Child Nutrition and Management, 36(1). http://www.schoolnutrition.org/Content.aspx?id=17259.

-

Healthy Schools Act. Office of the State Superintendent of Education. (n.d.). Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://osse.dc.gov/service/healthy-schools-act.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 18). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention violence prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Kumanyika, S. (2017). Getting to equity in Obesity Prevention: A new framework. NAM Perspectives, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, February 9). Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm.

- Lewallen, T. C., Hunt, H., Potts-Datema, W., et al. (2015). The whole school, whole community, whole child model: A new approach for improving educational attainment and healthy development for students. Journal of School Health, 85(11), 729–739. [CrossRef]

- Basch, C. E. (2011). Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the Achievement Gap. Journal of School Health, 81(10), 593–598. [CrossRef]

- Basch, C. E. (2011). Healthier students are better learners: High-quality, strategically planned, and effectively coordinated school health programs must be a fundamental mission of schools to help close the Achievement Gap. Journal of School Health, 81(10), 650–662. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M., Watts, E., Belson, S. I., & Snelling, A. (2020). Design and Implementation of a 5-Year School-Based Nutrition Education Intervention. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 52(4), 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M., Belson, S. I., McClave, R., et al. (2021). Healthy schoolhouse 2.0 health promotion intervention to reduce childhood obesity in Washington, DC: A feasibility study. Nutrients, 13(9), 2935. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M., Fuchs, H., Watts, E., et al. (2021). Development of a nutrition literacy survey for use among elementary school students in communities with high rates of food insecurity. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 17(6), 797–814. [CrossRef]

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen TL, Miller E, Bache SM, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel DP, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H (2019). “Welcome to the tidyverse.” Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, R. R., Frazier, S. L., Shernoff, E. S., Cappella, E., Mehta, T. G., Maríñez-Lora, A., Cua, G., & Atkins, M. S. (2018). Teacher Job Stress and Satisfaction in Urban Schools: Disentangling Individual-, Classroom-, and Organizational-Level Influences. Behavior therapy, 49(4), 494–508. [CrossRef]

- Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 262–273. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.M.; Zayco, R.A.; Herman, K.C.; Reinke, W.M.; Trujillo, M.; Carraway, K.; Wallack, C.; Ivery, P.D. Teacher and child variables as predictors of academic engagement among low-income African American children. Psychol Sch 2002, 39(4), 477-88. [CrossRef]

- McClave, R., Snelling, A. M., Hawkins, M., & Irvine Belson, S. (2023). Healthy Schoolhouse 2.0 Strides toward Equity in Obesity Prevention. Childhood obesity (Print), 19(3), 213–217. [CrossRef]

- Hauge, K, and Wan, P. (2019) Teachers’ collective professional development in school: A review study, Cogent Education, 6:1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).