1. Introduction

Melanoma represents a global health problem, being one of the most aggressive skin tumors. The treatment of this pathology has made great progress in recent years, with new staging techniques and the appearance of targeted molecules for the systemic treatment.

Although from an epidemiological point of view it represents only 1% of skin tumors, this neoplasia accounts for approximately 325,000 new cases and 57,000 deaths annually [

1]. Among the most important risk factors, exposure to UVA and UVB radiation should be mentioned, this mechanism inducing cellular changes that lead to an uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytes [

2]. Another important aspect is the family history, between 5 and 10% of patients with melanoma reporting that they have relatives with the same pathology, at the same time it is known that the risk of developing the disease is 2 times higher for those who have relatives with this pathology. Among the personal characteristics, those with light skin are more prone to the appearance of melanoma than the black population. This is also valid for people with blue eyes, blond or light hair, those who have immunosuppressive diseases, respectively those who present a large number of nevi [

3].

The methods of preventing this pathology can be summed up in the application of sunscreen with SPF > 30, or performing total body dermoscopy and repeating it dynamically in order to notice any changes in the skin lesions and detect the suspicious ones.

SLNB Concept

Cutaneous melanoma is characterized by the local proliferation of malignant melanocytic cells, followed by the extension to the lymphatic system, the main site of melanoma metastasis. A category of patients can develop satellite metastases located less than 2 cm from the primary tumor and in-transit metastases located between 2 cm and the first nodal site of drainage [

4].

The way of dissemination of melanocytic cells is that of the lymph nodes, this makes the difference between the localized disease and the systemic disease. Following research, it was demonstrated that the most important prognostic factor in terms of survival in cutaneous melanoma is represented by the lymph node involvement [

5]. It must be defined that the sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node that drains the lymph from the primary tumor, it constitutes a first filter for the neoplastic cells in their way of dissemination. The first mentions of this concept were in the 60s with parotid neoplasms, but the international recognition and validation of this method came in 1992 when Morton and Cochran presented the technique on a group of melanoma patients [

6]. The idea behind this concept was to evaluate patients in whom clinical or imaging metastases are not detected, by determining the first lymph node that drains the lymph from the tumor and analyzing it to determine if the disease has remained localized to the tumor or reached the stage with micrometastases.

SLNB indications

The SLNB technique is one of the most important staging techniques in cutaneous melanoma and the indications have been intensively studied and elaborated by the current guidelines. According to the NCCN guide, the indications are the following:

Tumors that are in the T1a stage, with a Breslow index of less than 0.8 mm, are considered in situ tumors, an early stage that does not require additional investigations, the disease being located strictly at the level of the tumor. However, there are indications for certain tumors that have a Breslow Index below 0.8 mm, if the histopathological and immunohistochemical examination reveals signs of increased aggressiveness of the tumor, such as ulceration or increased mitotic index.

Patients with small-thickness melanomas (<1 mm) have a low rate of sentinel node positivity of approximately 5%. Still, a subgroup of patients with an increased risk of sentinel node positivity exists. In these patients, other risk factors associated with sentinel node positivity are Clark level, mitotic rate, TIL (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes), lymphovascular invasion, VGP (vertical growth phase), and ulceration. In contrast, the presence of regression as a predictive factor is controversial. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, SLNB is recommended for patients in stage IB (>1 mm thick or 0.76–1.0 mm thick with ulceration or mitotic rate ≥1 per mm2 ) or stage II [

7].

Regarding melanomas with a thickness greater than 4mm (T4) and clinically negative nodes, the indication of sentinel lymph node biopsy is unclear and remains a recommendation. Patients with T4 tumor stage and clinically negative lymph nodes can be classified into the following clinical categories: stage IIB negative lymph node, non-ulcerated, stage IIC with negative node, ulcerated, stage IIIA positive node and non-ulcerated, IIIB with positive node ulcerated with predicted 5-year survival of 70, 53, 78, and 59 % [

8]. Stage IIC patients have a higher risk of recurrence and are not eligible for therapy since stage T4 melanomas have not been evaluated as extensively as those with intermediate tumor thickness. Patients in this category may be stratified using sentinel lymph node biopsy and given the option of adjuvant treatments [

9].

The multicenter, randomized phase 3 study KEYNOTE-716 demonstrated the benefits of adjuvant therapy with Pembrolizumab for stages IIB, and IIC resected melanoma with the improvement of survival outcomes in this population [

10].

Another particular situation is desmoplastic melanoma, in which the Breslow index does not correlate with SLN positivity, and SLN positivity does not correlate with disease-specific survival. This subtype of melanoma consists of more than 90% collagen stroma associated with hypocellularity with spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and lymphocyte islands. This subtype presents a minimal risk of distant metastases [

11].

The utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy after wide local excision is controversial due to the possible interruption of lymphatic drainage. However, some studies indicate that the correlation between preoperative and postoperative lymphoscintigraphy following wide excision and tissue rearrangement is between 89 and 95% [

12]. The recommendation is to biopsy the sentinel lymph node concomitant with resection and oncological margins, especially if rotation flaps or skin grafts were utilized for reconstruction since they affect the accuracy of the SLNB result [

7].

Sentinel lymph node biopsy contraindications

1. Patients with microsatellites or in-transit metastases who are initially staged as stage III of the illness do not require a sentinel lymph node biopsy [

13]. The NCCN guide recommends that patients with resectable isolated in-transit metastases can undergo SLNB.

2. The patient is in stage IV of the disease when organ metastases are present, and sentinel lymph node biopsy is no longer required for staging [

7].

3. Considering that the sentinel lymph node biopsy can provide access to immunotherapy, performing the sentinel biopsy is not contraindicated during pregnancy. The blue dye cannot be used due to the possibility of adverse allergic reactions, whereas the radioactive tracer 99mTc can be used without significant risks. Because the contrast agent is excreted through breast milk, breastfeeding must be discontinued for 4 to 24 hours after the administration.

4. Other contraindications include comorbidities that restrict the intervention (advanced age, poor general health status).

Sentinel lymph node – histopathological report

The identified lymph node is sent for histopathological examination using immunohistochemistry analysis and hematoxylin-eosin staining. Depending on the thickness of the tumor (Breslow index) determined by the histological analysis of the initial excisional biopsy, the intervention is continued with the excision of the safety margins of the scar [

7].

For a subgroup of patients, the histopathological analysis of the sentinel lymph node can be performed during the operation by analyzing the frozen sections in order to perform complete lymph node dissection during the procedure to avoid the costs and morbidity of a subsequent intervention [

14]. Permanent sections are superior to frozen sections because isolated tumor cells resemble macrophages, making it difficult to identify micrometastases in frozen sections. Additionally, the initial metastatic deposits are located subcapsular, and sometimes impossible to examine these in frozen sections. This analysis might lose tissue intended for evaluation or change the topography of the malignant cells at the lymph node level [

15].

Formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, sequential sectioning with hematoxylin-eosin staining, and immunohistochemical analysis with S100, HMB45, and MART-1 for molecular analysis remain the standard method of analysis of the SLN [

16].

The number of positive nodes, the amount of tumor tissue at the level of the lymph node, the location (subcapsular or intraparenchymal), as well as the presence of the extracapsular extension, are all identified in the histological analysis of the biopsied nodes [

17].

The Rotterdam criteria are used to classify patients according to the size of the tumor deposits into three groups: <0.1mm, 0.1-1mm, and >1mm in diameter. Patients with deposits greater than 1 mm in diameter have a higher probability of testing positive for other regional lymph nodes in addition to having a poor melanoma-specific survival (MSS) [

18].

Extracapsular extension and non-subcapsular metastases are also associated with decreased survival and an increased probability of developing macroscopic, clinically detectable metastases.

In more than 50% of cutaneous melanomas, the BRAF mutation activates the MAP kinase/ERK signaling pathway. In patients with localized or widespread metastatic disease, examination is required for therapeutic decisions. The guidelines recommend testing from the metastatic tissue as often as possible in patients with regional or systemic metastatic disease [

19]. According to Ascierto et al., BRAF contributes to the progression of melanoma by stimulating the secretion of VEGF and the vascularization of the tumor, as well as the factors that influence cell migration, integrin signaling, and cell contractility [

20].

Sentinel lymph node – the key to the appropiate treatment of the patient with melanoma

SLNB is the most important staging technique for melanoma patients without clinical ora imaging metastases, being the only method that can upstage a patient with stage III. At the same time, after this correct diagnosis of the stage of the disease, all therapeutic options and additional investigations can be considered [

7].

Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the sentinel lymph node biopsy function. Results from the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1), which included 1347 stage I/II melanoma patients suitable for SLNB, demonstrated the utility of this technique in the stratification of melanomas with intermediate thickness [

21].

The first randomized phase III study to evaluate the efficacy of CLND in patients with positive SLNB, including both patients with tumor burden <1 mm and those with tumor burden >=1 mm, was the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group-Sentinel Lymph node Trial (DeCOG-SLT). They concluded that there were no significant differences between CLND versus periodic nodal ultrasonography follow-up [

22].

The findings of phase 3 MSLT-II trial support those of the DeCOG-SLT study. In this study comparing sentinel node biopsy with complete lymph node dissection to sentinel node biopsy with active follow-up and periodic soft-tissue ultrasound and dissection if signs of lymph node metastasis appear. There was no difference in melanoma-specific survival after a median follow-up of 43 months for 1934 patients [

23].

These findings are limited by the nodal low tumor burden, and the small cohort of patients makes it difficult to assess the efficacy of total nodal dissection in high-risk patients (with high tumor burden, TB >1 mm).

All patients with positive SLNB are no longer recommended to undergo CLND, especially those who are not at risk for developing metastases in the other lymph nodes. As a consequence, patients with a low risk of distant metastases but a high probability of regional metastases over time may benefit from immediate CLND [

24].

The aim of the study is to investigate the variability of lymphatic drainage in the case of the sentinel lymph node of melanomas located on the trunk.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study there were included 62 cases of melanoma located on the trunk, patients operated on between July 2019 and March 2023, in a private hospital unit in Bucharest, Romania. The inclusion criteria for the present study were melanomas with a Breslow index of at least 0.8 mm and the absence of imaging and clinical detectable metastases. Also, the patients are over 18 years old and the SLNB was performed at a maximum of 6 weeks after the melanoma biopsy. The exclusion criteria were represented by melanomas with distant metastases, patients with severe associated cardiovascular diseases or low performance index that presented contraindications for the anesthesia, respectively age below 18 years and patients with melanoma location other than the trunk.

The indication to perform SLNB is obtained following a multidisciplinary meeting attended by doctors from the specialties of general surgery, plastic surgery, medical oncology, histopathology, dermatology, nuclear medicine and the anesthesiologist which analyze the case and determines the appropriateness of the intervention. The surgical procedure is performed on the same day as the injection of the radiotracer, so that the radioactive charge of the lymph nodes is as high as possible.

For the comparison analysis the patients were divided into two subgroups as follows the upper trunk melanoma (UpM) represented by the anterior and posterior thoracic region, and lower trunk melanoma (LoM) represented by abdomen and the lombar region.

The characteristics studied in this work were demographic, such as age, sex, BMI, and also those related to the pathology of skin melanoma. The main variables in this study were represented by tumor stage, Breslow index, location of sentinel lymph nodes, node positivity, type of anesthesia, average time of surgery. The results were reported as number and frequency for ordinal values and median with minimum and maximum value for numerical data. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0. The tests performed for the comparison were Pearson's chi square test and Mann–Whitney U test with a significant result at p<0.05.

SLNB surgical technique

The SLNB technique is used to determine the first lymph node that drains from the tumor, being unanimously accepted as a very reliable method of staging the disease, by clarifying the existence of any tumor dissemination at the lymphatic level. The procedure begins by performing a lymphoscintigraphy on the day of the surgical intervention or at the earliest approximately 24 hours before it, when it is injected a radiotracer (Technetium Tc-99m) at 1 cm distance from the scar of the excised melanoma. The colleagues from nuclear medicine provide the results of this investigation with the determination of the lymphatic route and the drainage to the sentinel lymph node. In order to increase the sensitivity of the detection, a blue dye will be injected around the scar when the patient arrives in the operating room, after which it will take about 15 minutes to reach the level of the sentinel lymph node. The area where the sentinel lymph node is supposed to be will be checked with the gamma probe and the incision will be made in such a way as to provide the best possible exposure of the respective area to facilitate the dissection of the surrounding structures. Finally, the identification of the sentinel lymph node is done in a dual way: with the gamma probe thus determining the radioactivity of the lymph node, respectively, the accumulation of the blue dye.

It should be mentioned that the measurement of the lymph node radioactivity is done in 3 moments: preoperative, intraoperative and ex-vivo. Also, after the sentinel lymph node has been excised, the operative field will be checked once again for the possibility of the presence of another radioactively charged lymph node (if it has a radioactive value of more than 10% of the value of the “hottest lymph node”).

3. Results

In this study, a total of 62 cases were analyzed. Among them, 62.9% (39 cases) were diagnosed with upper melanoma, while the remaining 37.1% (23 cases) were diagnosed with lower melanoma. The characteristics of patients and the comparison between upper and lower trunk melanoma cases is showed in

Table 1. The median age of the patients included in the study was 55 years, with a range of 34 to 78 years. Specifically, patients diagnosed with lower carcinoma had a median age of 53 years (min-max=33-77). However, the difference in age between patients with upper and lower melanoma was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.782). In terms of gender distribution, 36 cases (58.1%) were male out of the total, with 22 cases (56.4%) being male among the LoM group. Additionally, the study examined the body mass index (BMI) of the patients, which showed a median of 23.7 kg/m2 (ranging from 19.8 to 30.6 kg/m2) for upper melanoma cases and 24.1 kg/m2 (ranging from 19.9 to 29.2 kg/m2) for lower melanoma cases, indicating no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.291). The tumor stage distribution revealed that among all cases, 32.3% were classified as pT1, 14.5% as pT2, 24.2% as pT3, and 29.0% as pT4. When comparing UpM and LoM no statistically significant differences were observed in the distribution of tumor stages (p = 0.413).

The Breslow thickness, which measures the depth of the melanoma, was assessed in the study with a median of 2.3 (0.5-12.5). When comparing UpM with LoM groups regarding the Breslow index there was no significant difference (median of 2.3 (0.5-12.5 for UpM vs 2.3 (0.8-9.3) for LoM, p = 0.511).

Regarding the number of LN excided per patients, 44 patients had only one LN biopsy while 18 had two LN excided, and there were two cases with three LNB.

The primary lymph node localization was examined, and the analysis revealed that 9.7% of cases had cervical LN involvement, 71.0% had axillary LN involvement, and 19.4% had inguinal LN involvement. When comparing upper and lower melanoma, a statistically significant difference was observed in the distribution of LN localization (p < 0.001), with UpM cases showing a higher percentage of axillary LN involvement (84.6%) compared to LoM cases (33.3%).

Regarding the secondary LN localization, a subgroup analysis was conducted on 20 cases. Among them, 10.0% had cervical LN involvement, 80.0% had axillary LN involvement, and 10.0% had inguinal LN involvement. However, no significant difference was found in the distribution of secondary LN localization between UpM and LoM cases (p = 0.057). Furthermore, analyzing the LN involvement for the LoM group, for the first LN almost half of the patients had axillary involvement (47.8%), while for the second LN excided 66,7% were from inguinal region, with an additional third lymph node from inguinal side as well.

The presence of positive LN, indicating the presence of cancer cells in the lymph nodes, was investigated. It was observed that 25.8% of all cases had positive LN involvement, with 30.8% in UpM patients and 17.4% in LoM patients. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.245).

Anesthesia type administered during the surgical procedure was also analyzed. Among patients with upper melanoma, all cases underwent general anesthesia, while none received local anesthesia. In contrast, patients with LoM had 39,1% of cases which only required local anesthesia, with a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.001).

The surgery duration had a median of 120.0 minutes (ranging from 75 to 195) for upper melanoma cases and 110.0 minutes (ranging from 70 to 200) for lower melanoma cases. Although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.056), it suggests a slightly longer surgery duration for UpM cases.

Regarding postoperative outcomes, the rate of reintervention was low, with only 1.6% of all cases requiring additional surgical interventions. The only one case which required reintervention belonged to LoM group (2.6%).

The healing periods for the melanoma site and the lymph nodes were also recorded. The median period of healing for the melanoma site was 12 days for both UpM and LoM cases, showing no significant difference (p = 0.833). Similarly, the median period of healing for the LN was 8 days (ranging from 7 to 9) for UpM and 8 days (ranging from 7 to 8) for LoM, indicating no significant difference (p = 0.373).

Additionally, the presence of the BRAF gene was registered in a subset of 14 cases, with a total of 10 cases having a positive BRAF gene. Among them 6 were from patients with UpM and 4 from patients with LoM, with no significant difference observed between the two groups (p =1.000). This indicates a similar prevalence of the BRAF gene in both upper and lower trunk melanoma.

The total number of sentinel lymph nodes identified in the study was 84, the distribution is illustrated in

Table 2. Among these, 54 (64.3%) were from patients diagnosed with UpM, with 13 (24.1%) of them being positive for malignancy. In contrast, 30 (35.7%) were associated with LoM, and out of these, 6 (20%) were positive for malignancy (p=0.264).

In terms of lymph node involvement, the analysis revealed that among all cases of trunk melanoma in this study, 9.5% had cervical LN involvement, 73.8% had axillary LN involvement, and 16.7% had inguinal LN involvement.

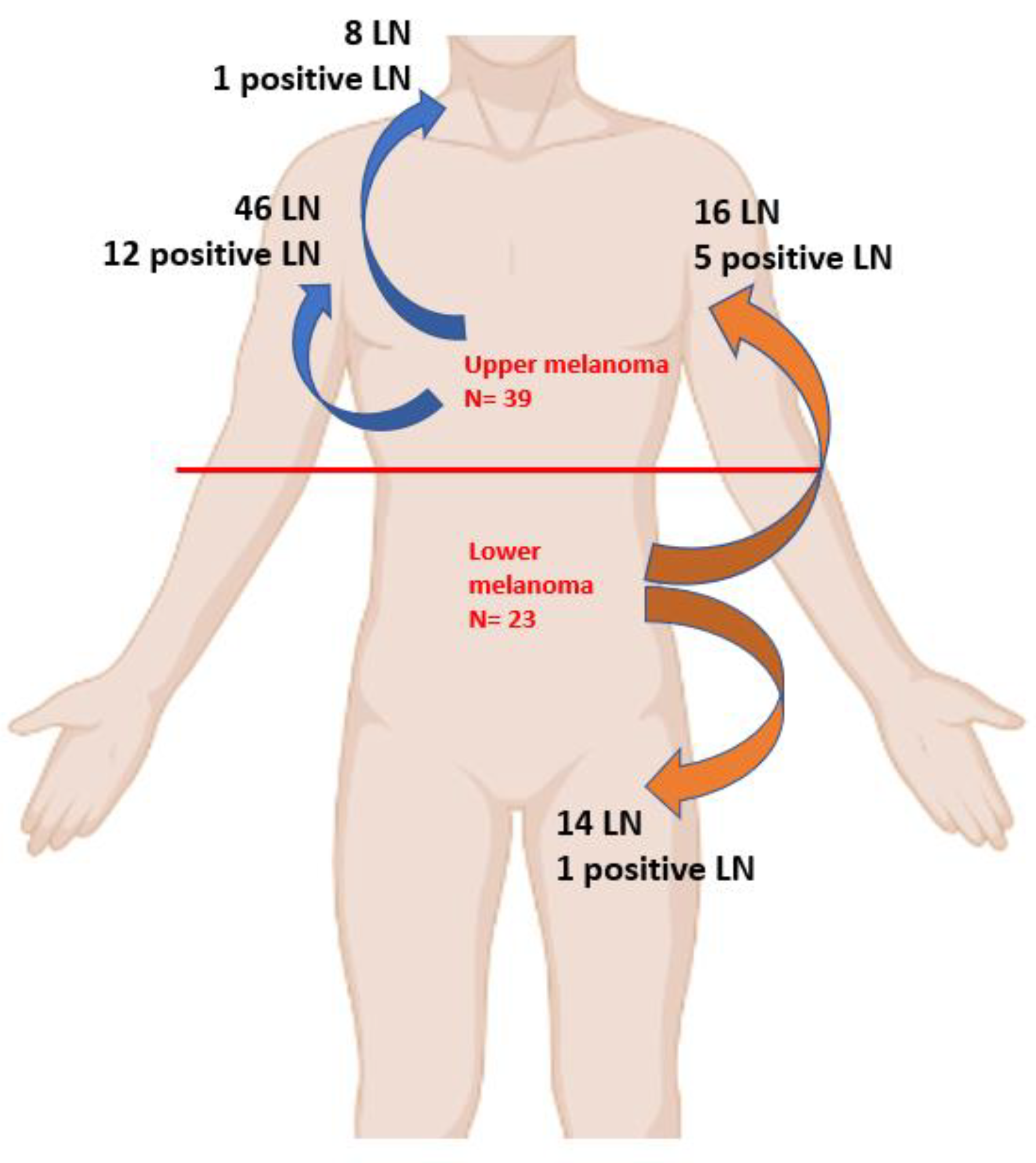

As illustrated in

Figure 1, in upper melanoma patients out of 54 LN identified, 13 were positive, with a total of 12 positive LN from axillar basin and only 1 from cervical region.

On the other hand, for cases diagnosed with lower trunk melanoma, no LN involvement was observed in the cervical LN. However, 16 of cases out of 30 had axillary LN involvement, while 14 had inguinal LN. From LoM subgroup a total of 6 cases had positive LN, with 5 cases in axillar region and only one in inguinal region.

Moreover, analyzing the variability of multiple basin drainage, among the 20 patients with a minimum of 2 sentinel lymph nodes identified, 7 had LN involvement in 2 basins. However, only 1 of these cases showed positivity for malignancy, specifically in the posterior thoracic site with axillary and cervical drainage.

Furthermore, among the 20 patients with a minimum of 2 sentinel lymph nodes, 15 had upper melanoma (with 5 cases showing drainage in 2 basins), while 5 had lower melanoma (with 2 cases showing drainage in 2 basins).

4. Discussion

This study emphasized the distribution of lymph nodes regarding the melanoma location on trunk. From a total of 62 patients included, upper trunk melanoma had a higher frequency than lower trunk location for such tumors (62.9% vs 37.1%). The median of age of the patients included in the study was 54.5 years for the hole group with 55 years old for patients diagnosed with upper trunk melanoma, results comparable to that obtained by a Dutch study carried out on a larger group of 1192 patients with melanoma located in the upper trunk, where the average age obtained was 56 years old [

25].

Related to the gender distribution, the study emphasized the fact that the male gender predominates with 58.1% of cases, this value being close to that obtained by an American trial based on a cohort of 178,000 cases from the period 2004-2014, where in the case of melanomas located on the trunk, 66.1% were male patients [

26]. Moreover, in our study male gender was more frequent among subjects diagnosed with lower trunk melanoma than those with upper trunk melanoma. Another study carried out in Sweden, shows a predominance of the male sex in the case of melanomas of the trunk, the proportion being 53%, compared to 47% for the female sex [

27].

Another important aspect of the current study is represented by the Breslow index, the median value being 2.3 mm in both the upper and lower melanoma regions. The specialized literature confirms this value, a study conducted in the USA that included 818 cases of melanoma of the trunk with an average Breslow index value of 2.3 mm [

28].

However, the distribution according to the T stage of the tumor differs a lot from other populations. If in the current work, T1 tumors represented the highest percentage of cases, 32.3%, while T2 represented the other extreme, 14.5% of cases, the literature shows completely different values, tumors in stages T3 and T4 representing the most of the cases, with 35% and 22%, respectively [

27].

A study carried out in Portugal shows a different distribution regarding the T staging of tumors, with the exception of T3 where the values are almost equal. This study also shows a predominance of tumors located at the level of the upper trunk, this result being in accordance with what we obtained in our study, the tumors located at the upper level being 62.9% [

29].

Regarding the identification of the sentinel lymph node, the results of the study showed that there are tumors that can drain in one lymphatic way, others through 2 ways and some of them can even have 3 sentinel lymph nodes. The variability of the lymphatic channels is given by the location of the primary trunk tumor in relation to the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphatic basins, with significant statistical results when compared upper region with lower region of trunk melanoma in our findings (p<0.05). Melanomas of the upper trunk had predominantly sentinel lymph nodes in the axillary lymph basin (84.6% for the first LNB, 85.7% for the second LNB, and 100%for the third LNB, respectively). In contrast, for melanomas of the lower trunk the results on LN location varied, if the first sentinel node was in somewhat similar proportions between the axillary region and groin (47.8% vs. 52.2%), in the case of the second sentinel lymph node, the axillary region had 2 thirds of the cases (66.7% vs. 33.3%). In both regions, both upper and lower trunk melanomas, there was one case with a 3rd sentinel lymph node present at the axillary level.

In the specialized literature, it is confirmed that melanomas located on the trunk are those that could have multiple lymphatic drainage regarding the sentinel lymph node, a study conducted on 135 patients with 61 cases of multiple drainage (45.2%) [

29], respectively another study showing on 352 trunk melanomas that 77 cases had multiple drainage (21.9%) [

30]. It should be mentioned that another study carried out in Italy on 656 patients revealed that 167 cases had multiple drainage (25.4%) [

31]. All these results are comparable to those obtained in our study in which there are 20 patients with multiple drainage, respectively 32.2% of the cases.

The positivity of the sentinel lymph node is closely related to the T stage of the melanoma, respectively to its Breslow index. In our study, which had a total of 62 patients, 84 lymph nodes were analyzed, 22.6% being positive, 22.6% being positive. A comparative study in which there were 39 patients with melanoma and in which SLNB was performed, a total of 121 lymph nodes were excised, of which 22 positive nodes (18.1%) were found at the histopathological examination, totaling 13 patients with a positive sentinel node [

25].

Regarding the duration of the surgical intervention, there is an important difference between the two locations, superior and inferior trunk. It should be mentioned that this duration involves the sentinel lymph node biopsy, the excision with safety oncological margins and the closure of the wound, in some areas the graft taken by the plastic surgeon is needed. The median time spent more with interventions at the level of the upper trunk presupposes dissection in areas with lymphatic basins and important vascular structures, as we find in the cervical lymph nodes area (120 vs. 110 minutes).

The type of anesthesia chosen represents another stage in these interventions. If at the level of the lower trunk, we can opt for a spinal anesthesia that can reach both the area of the melanoma and the region of the sentinel lymph node, if it is only in the inguinal region, for melanomas located at the level of the upper trunk, general anesthesia was preferred in its entirety by oro-tracheal intubation, the difference between the two being statistically significant (p<0.001).

Another important feature of our study is represented by lower trunk melanomas that had sentinel nodes located at the axillary level, 16 out of 30 nodes (53.3%) being present in this lymphatic basin. Also, another interesting result obtained is that among the positive sentinel nodes of melanomas of the lower trunk, 5 out of 6 nodes (83.3%) are at the axillary level, something that could be further investigated on a larger cohort in order to research the lymphatic pathways of melanomas depending on the location of the primary tumor. In the literature, another study that highlighted lymphatic drainage in different locations of melanomas showed that in the case of 67 patients with trunk melanoma who underwent SLNB, 35 axillary nodes (28.6%) were detected [

32]. The presence of positive LN varied between the groups, with a higher percentage observed in upper melanoma cases with axillar basin being the most frequent location for all trunk melanomas (85.1%).

5. Conclusion

These findings contribute to our understanding of the characteristics and outcomes of melanoma of the trunk by upper versus lower region, emphasizing the importance of considering sentinel lymph node involvement and type of anesthesia in the management of these cases. The small number of patients is a limitation of this study, which is why further studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate and extend these findings.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, F.B. and M.L.; methodology, D.G.; software, D.S.; validation, A.B., C.A. and D.D.; formal analysis, L.V.; investigation, D.D. and D.G.; resources, M.L.; data curation, L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.; writing—review and editing, T.P.; visualization, C.A. and D.S.; supervision, M.L. and T.P.; project administration, A.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dr Leventer Centre (no 1/11.04.2023).” .

Informed Consent Statement

“Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Ferlay J., Ervik M., Lam F., Colombet M., Mery L., Piñeros M., Znaor A., Soerjomataram I., Bray F. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: [(accessed on 10 May 2021)]. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Arisi M, Zane C, Caravello S, Rovati C, Zanca A, Venturini M, Calzavara-Pinton P. Sun Exposure and Melanoma, Certainties and Weaknesses of the Present Knowledge. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018 Aug 30;5:235. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Med Sci (Basel). 2021 Oct 20;9(4):63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, Hauschild A, Arenberger P, Basset-Seguin N, Bastholt L, Bataille V, Del Marmol V, Dréno B, Fargnoli MC, Forsea AM, Grob JJ, Höller C, Kaufmann R, Kelleners- Smeets N, Lallas A, Lebbé C, Lytvynenko B, Malvehy J, Moreno-Ramirez D, Nathan P, Pellacani G, Saiag P, Stratigos AJ, Van Akkooi ACJ, Vieira R, Zalaudek I, Lorigan P; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 1: Diagnostics: Update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Jul;170:236-255. 12 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han D, Han G, Duque MT, Morrison S, Leong SP, Kashani-Sabet M, Vetto J, White R, Schneebaum S, Pockaj B, Mozzillo N, Sondak VK, Zager JS. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Is Prognostic in Thickest Melanoma Cases and Should Be Performed for Thick Melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021 Feb;28(2):1007-1016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, Economou JS, Cagle LA, Storm FK, Foshag LJ, Cochran AJ. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992 Apr;127(4):392-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines – Melanoma: Cutaneous, Version 2 - 2023. C: Guidelines – Melanoma.

- Dickson PV, Gershenwald JE. Staging and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2011 Jan;20(1):1-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyorki DE, Sanelli A, Herschtal A, Lazarakis S, McArthur GA, Speakman D, Spillane J, Henderson MA. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in T4 Melanoma: An Important Risk-Stratification Tool. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Feb;23(2):579-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke JJ, Ascierto PA, Carlino MS, Gershenwald JE, Grob JJ, Hauschild A, Kirkwood JM, Long GV, Mohr P, Robert C, Ross M, Scolyer RA, Yoon CH, Poklepovic A, Rutkowski P, Anderson JR, Ahsan S, Ibrahim N, M Eggermont AM. KEYNOTE-716: Phase III study of adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected high-risk stage II melanoma. Future Oncol. 2020 Jan;16(3):4429-4438. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dear, VG. Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017 Sep;37(3):417-430. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyan S, Ali-Salaam P, Cheng DW, Truini C. Reliability of lymphatic mapping after wide local excision of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007 Aug;14(8):2377-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluemel C, Herrmann K, Giammarile F, Nieweg OE, Dubreuil J, Testori A, Audisio RA, Zoras O, Lassmann M, Chakera AH, Uren R, Chondrogiannis S, Colletti PM, Rubello D. EANM practice guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015 Oct;42(11):1750-1766. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatib W, Hertzenberg C, Jewell W, Al-Kasspooles MF, Damjanov I, Cohen MS. Utility of frozen-section analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy specimens for melanoma in surgical decision making. Am J Surg. 2008 Dec;196(6):827-32; discussion 832-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, VG. Use of frozen sections in the examination of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with melanoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2008 May;25(2):112-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amy E Somerset, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Patients with Melanoma, Updated: Oct 14, 2021. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/854424-overview#a1.

- Prieto, VG. Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017 Sep;37(3):417-430. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodin KE, Fimbres DP, Burner DN, Hollander S, O'Connor MH, Beasley GM. Melanoma lymph node metastases - moving beyond quantity in clinical trial design and contemporary practice. Front Oncol. 2022 Oct 14;12:1021057. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, Hauschild A, Arenberger P, Basset-Seguin N, Bastholt L, Bataille V, Del Marmol V, Dréno B, Fargnoli MC, Forsea AM, Grob JJ, Höller C, Kaufmann R, Kelleners-Smeets N, Lallas A, Lebbé C, Lytvynenko B, Malvehy J, Moreno-Ramirez D, Nathan P, Pellacani G, Saiag P, Stratigos AJ, Van Akkooi ACJ, Vieira R, Zalaudek I, Lorigan P; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 1: Diagnostics: Update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Jul;170:236-255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM, Grob JJ, Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Maio M, Palmieri G, Testori A, Marincola FM, Mozzillo N. The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma. J Transl Med. 2012 Jul 9;10:85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachare SD, Brinkley J, Wong JH, Vohra NA, Zervos EE, Fitzgerald TL. The influence of sentinel lymph node biopsy on survival for intermediate-thickness melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Oct;21(11):3377-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y. The Role and Necessity of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Invasive Melanoma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019 Oct 22;6:231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Andtbacka RH, Mozzillo N, Zager JS, Jahkola T, Bowles TL, Testori A, Beitsch PD, Hoekstra HJ, Moncrieff M, Ingvar C, Wouters MWJM, Sabel MS, Levine EA, Agnese D, Henderson M, Dummer R, Rossi CR, Neves RI, Trocha SD, Wright F, Byrd DR, Matter M, Hsueh E, MacKenzie-Ross A, Johnson DB, Terheyden P, Berger AC, Huston TL, Wayne JD, Smithers BM, Neuman HB, Schneebaum S, Gershenwald JE, Ariyan CE, Desai DC, Jacobs L, McMasters KM, Gesierich A, Hersey P, Bines SD, Kane JM, Barth RJ, McKinnon G, Farma JM, Schultz E, Vidal-Sicart S, Hoefer RA, Lewis JM, Scheri R, Kelley MC, Nieweg OE, Noyes RD, Hoon DSB, Wang HJ, Elashoff DA, Elashoff RM. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 8;376(23):2211-2222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoud SJ, Perone JA, Farrow NE, Mosca PJ, Tyler DS, Beasley GM. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Completion Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018 Sep 19;19(11):55; Erratum in: Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019 Aug 29;20(10):76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenstra HJ, Klop WM, Speijers MJ, Lohuis PJ, Nieweg OE, Hoekstra HJ, Balm AJ. Lymphatic drainage patterns from melanomas on the shoulder or upper trunk to cervical lymph nodes and implications for the extent of neck dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Nov;19(12):3906-12. 11 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon CM, Mehta NK, Li H, Nguyen SA, Koochakzadeh S, Elston DM, Kaczmar JM, Day TA. Anatomic Region of Cutaneous Melanoma Impacts Survival and Clinical Outcomes: A Population-Based Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 15;15(4):1229. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon D, Smedby KE, Schultz I, Olsson H, Ingvar C, Hansson J, Gillgren P. Sentinel node location in trunk and extremity melanomas: uncommon or multiple lymph drainage does not affect survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Oct;21(11):3386-94. 28 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadaki N, Li R, Parrett B, Sanders G, Thummala S, Martineau L, Cardona-Huerta S, Miranda S, Cheng ST, Miller JR 3rd, Singer M, Cleaver JE, Kashani-Sabet M, Leong SP. Is head and neck melanoma different from trunk and extremity melanomas with respect to sentinel lymph node status and clinical outcome? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Sep;20(9):3089-97. 7 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado FJ, Soeiro P, Brinca A, Pinho A, Vieira R. Does the pattern of lymphatic drainage influence the risk of nodal recurrence in trunk melanoma patients with negative sentinel lymph node biopsy? An Bras Dermatol. 2021 Nov-Dec;96(6):693-699. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribero S, Quaglino P, Osella-Abate S, Sanlorenzo M, Senetta R, Macrì L, Savoia P, Macripò G, Sapino A, Bernengo MG. Relevance of multiple basin drainage and primary histologic regression in prognosis of trunk melanoma patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Sep;27(9):1132-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribero S, Osella-Abate S, Pasquali S, Rossi CR, Borgognoni L, Piazzalunga D, Solari N, Schiavon M, Brandani P, Ansaloni L, Ponte E, Silan F, Sommariva A, Bellucci F, Macripò G, Quaglino P. Prognostic Role of Multiple Lymphatic Basin Drainage in Sentinel Lymph Node-Negative Trunk Melanoma Patients: A Multicenter Study from the Italian Melanoma Intergroup. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 May;23(5):1708-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson JF, Uren RF, Shaw HM, McCarthy WH, Quinn MJ, O'Brien CJ, Howman-Giles RB. Location of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with cutaneous melanoma: new insights into lymphatic anatomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1999 Aug;189(2):195-204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).