1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), namely Crohn's Disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic, relapsing inflammatory immune-mediated disorders. Many patients affected by IBD need immunosuppressant therapies which are known to be associated with a higher risk of contracting opportunistic infectious diseases and of pre-neoplastic or neoplastic lesions such as cervical high-grade dysplasia and cancer. [

1,

2] Many of these potentially harmful diseases such as hepatitis B (HBV), flu, chickenpox, herpes zoster virus (HZV), pneumococcal pneumonia or human papilloma virus (HPV) infection can be prevented by vaccines. [

3] Each drug used in the treatment of IBD should be classified according to the degree of immunosuppression induced in the patient.

According to European Crohn´s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines, patients treated with anti-tumour necrosis alfa (antiTNF), corticosteroids, azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine and those on combination therapies are at increased infectious risk. Although some of the latest therapies approved for IBD treatments such as ustekinumab seem to have a lower degree of immunosuppression compared to anti-TNF, they are not risk-free drugs for infections. For example, patients of all ages treated with tofacitinib are at higher risk of Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. [

4] Several guidelines suggest investigating patients’ vaccination status before starting any treatment, and performing vaccinations against VPDs when required. [

3,

5,

6] Nevertheless, despite the increased risk of infections, vaccination rates in IBD patients are known to be suboptimal and may also be lower than vaccination rates in the general population. [

7,

8,

9,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the debate around vaccinations in the general population rose to prominence again due to concerns about mass vaccinations. To the best of our knowledge our study was the first national post-pandemic survey to investigate vaccination coverage against VPDs in IBD patients.

The aim of the study was to investigate the vaccination coverage against VPDs, attitude towards vaccinations and its possible determinants among a national cohort of IBD patients. Moreover, we aimed to evaluate whether the low vaccination coverage among IBD patients was mainly influenced by vaccination hesitancy or by suboptimal prescription by Healthcare Providers (HCPs).

2. Materials and Methods

Between February 10 and February 19, 2021, the Italian IBD patients’ association (

Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell’Intestino, also known as AMICI) distributed an anonymous online questionnaire to their adult members via mailing lists and social media platforms. The questionnaire was sent in one single mailing without any reminder, and only one post was made on AMICI social media platforms Facebook and Instagram (Meta platforms inc., Menlo Park, USA). The questionnaire consisted of an adapted version of a previously validated questionnaire on vaccine hesitancy [

10] and was divided into 2 sections seeking information on: (1) sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and IBD characteristics, (2) attitude towards vaccinations in general. Patients were asked to self-report their previous vaccinations and their attitudes towards them (with multiple-choice questions). Attitudes towards vaccination were defined as: opposed to vaccinations, indifferent, or in favour of vaccinations. The questionnaire was divided into seven sections and is reported in the supplementary material.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for the categorical (qualitative) variables, and quantitative variables were summarized by their means and range. All variables found to have a statistically significant association with vaccination attitude in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression model. All variables with a p value ≤ 0.20 were selected in the multivariate model to guarantee a conservative approach. A backward stepwise regression model was used. The crude odds ratio (crude OR) and the adjusted OR (AdjOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated in the logistic regression model. The level of significance chosen for the multivariate logistic regression analysis was 0.05 (2-tailed). We entered all the information into a database created with Epi Info™ 3.5.4 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). All the data were analysed using the statistical software package Stata/MP 12.1 (StataCorp, L.P.; College Station, TX, USA).

2.2. Ethical Statement

The study was approved by the Scientific Advisory Board Ethics Committee of AMICI ETS. All the subjects received an email explaining the rationale of the study and the digital informed consent to participate and had to sign the digital informed consent before participating. After they agreed, the subjects were directed via a link to an online structured questionnaire on the SurveyMonkey platform (Momentive Inc., San Mateo, CA 94403 United States). [

11]

3. Results

The questionnaire was sent to 4720 patients and had a response rate of 26.5% (1252 patients including 729 women, median age 47.7, interquartile range 37–58). 49% of participants reported suffering from Crohn’s disease, 48.9% from ulcerative colitis. Completed questionnaires were received from each of the 20 Italian regions. Socio-demographic, lifestyle and clinical characteristics of the study population are described in

Table 1.

Of note, 46.7% of the patients reported being treated with biologic or immunosuppressive drugs.

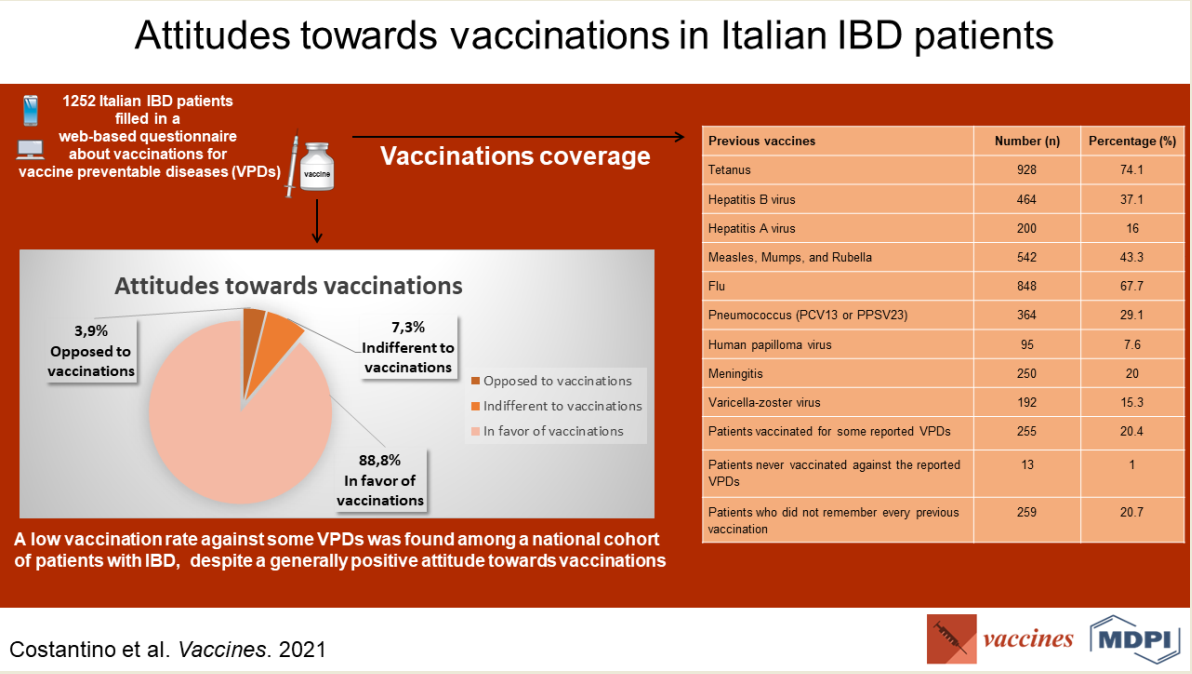

Patients declared being vaccinated against the following diseases: 74.1% tetanus, 67.7% flu (during last season), 43.3% (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) MMR, 37.1% HBV, 29.1% pneumococcus (pneumococcal conjugated 13-valent vaccine,

PCV13, or pneumococcal polysaccharide 23-valent vaccine, PPSV23), 20% meningitis, 16% hepatitis A (HAV), 15.3% VZV, 7.6% HPV. Two hundred and fifty-nine (20.7%) did not remember every previous vaccination. Reports of previous vaccination history are summarized in

Table 2.

The participants’ attitudes towards vaccinations in the study population are reported in

Table 3.

In summary, among the respondents, 1154 (92.2%) stated they wanted to be vaccinated in the future against VPDs. A previous negative experience with vaccinations, whether personal or referred by relatives, was reported by 163 (13.2%) among the 1238 respondents to this specific question. One thousand one hundred and twelve (88.8%) stated a positive attitude towards vaccination, 91 (7.3%) were indifferent, 49 (3.9%) reported being opposed to vaccinations. Four hundred and fifty-six (36.4%) stated that the main reason for vaccination adherence was their IBD.

The main determinant associated with a positive attitude towards vaccinations was the belief of possible return of VPDs with decline of vaccination coverage rates (AdjOR 5.67, 95% CI 3.45-9.30, p-value <0.001). The vaccination adherence motivated by their IBD was at the limit of significance (1.72 (0.99 – 2.97)

Table 4.

Other factors, such as gender, age, education level, number of family member and marital status,

disease type, adherence to the IBD therapy, disease duration, type of therapy (immunosuppressive

or not), smoking habit, use of complementary and alternative medicine, did not influence the attitude

towards vaccinations.

4. Discussion

Our results show a general positive attitude towards vaccinations, mainly influenced by the awareness of possible return of opportunistic infections with the decline of vaccinations rates. Only 3.9% of patients were opposing vaccinations. Nevertheless, there is still suboptimal vaccination coverage against VPDs in this national cohort of IBD patients, with almost half of patients (46.7%) taking immunosuppressive or biologic therapies.

Since most patients have a positive attitude towards vaccinations, this suggests a possible role of physicians in under-prescribing vaccinations to this population, possible difficulty in organizing vaccinations, and possible low patient awareness.

All these problems may be solved by specific vaccination campaigns among both HCPs and IBD patients, aimed at increasing vaccination rates against VPDs.

4.1. Overview of Vaccine Recommendations in Patient with IBD

Compared to the rest of the population, patients affected by IBD are known to be at higher risk of contracting some vaccine preventable diseases such as flu and pneumonia. [

12,

13] IBD patients affected with flu are at higher risk of hospitalization and developing serious complications. IBD patients on immunosuppressive treatment are at higher risk of contracting pneumonia and have an increased mortality rate when hospitalized. [

12] For these reasons annual vaccinations against flu with inactivated vaccines are recommended in all patients including those on immunosuppressive therapy. Vaccination against pneumonia is also recommended at the time of IBD diagnosis. [

5,

6] Nevertheless, the vaccination coverage for flu in these patients is known to be suboptimal. [

9,

13] Other potentially harmful VPDs include

Neisseria meningitidis infection which can cause meningitis with a high risk of complications. Anti-meningococcal vaccination can be safely administered in IBD patients independently of the therapies they are taking. [

5,

6] Before starting immunosuppressive treatment, the immunization status of IBD patients for other diseases including HPV, HBV and VZV should also be checked. [

3,

5,

6] HPV can cause anogenital and cervical cancer, therefore both men and women should be encouraged to get vaccinated before starting any treatment for IBD. Moreover, all women under immunosuppressants or steroid therapy should be encouraged to get cervical cancer screening at a higher frequency than the rest of the population, because of the reported increased risk of cervical cancer precursor lesions. [

14,

15,

16] HBV antibody titers should be tested before starting any patient on immunosuppressive treatment due to the risk of HBV reactivation which can result in hepatitis and hepatic failure. Patients with an antibody titer <10 mUI/mL, particularly, should be vaccinated or revaccinated, according with national or regional guidelines. [

3]

It is well known that IBD patients, particularly those on treatment with immunosuppressives, biological drugs or small molecules, have greater risk of severe primary VZV infection and of herpes zoster (HZ). The former can be life-threatening in immunocompromised patients, while the latter most frequently affects patients aged over fifty and those on combined immunosuppressive treatment. For this reason, vaccination against VZV is recommended in IBD patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. [

17,

18,

19] Recombinant herpes zoster vaccine (RZV) is the preferred vaccine for patients with IBD disease, given its efficacy and safety. If RZV is not available, a live zoster vaccine [ZVL] is recommended in immunocompetent patients with IBD aged ≥50 years. [

3]

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study has some limitations that must be addressed. First, people who filled the questionnaire could have had a greater willingness to be vaccinated than those who did not answer, representing a possible response bias. A similar limitation could be the possible selection bias arising from the delivery of the questionnaire through the mailing list of AMICI ETS. Those patients may be more concerned about their disease or have a more proactive attitude. Another possible limitation of the study is that the median age of the responders was 47.7. There is a possible higher inclination towards vaccination in middle age patients due to heightened fears of complications related to infectious diseases. A major limit of our survey is the use of a self-reported questionnaire instead of vaccination cards or official records. 20.7% of the responders could not remember every previous vaccination, despite all being members of a patients’ association. Despite this, a questionnaire still represents the most efficient way to investigate not only the vaccination status but also a great amount of data and parameters regarding vaccination hesitancy in a national cohort in such a short period. Furthermore, studies which compared the accuracy of self-reported vaccination status with official records showed comparable results. [

20,

21,

22] In 2021, Smith et al. demonstrated that self-report was an effective way to determine flu immunization status which provided useful information prior to administering pneumococcal vaccines in patients with IBD. [

21] Another study conducted on smallpox vaccines indicated a substantial and acceptable agreement between participants self-reporting of vaccination status, and electronic documentation. [

22]

Despite these limitations, our survey has many strengths.

First, every patient filled the questionnaire deliberately without remuneration. At the time of writing, this study represented the first post-pandemic national survey investigating vaccine status and attitude towards vaccination in a national IBD cohort. The questionnaire was sent through the mailing list of the major national patients’ association so it gives a realistic picture of the vaccination status among the Italian IBD population. The questionnaire was an adapted version of a previously validated questionnaire on vaccine hesitancy [

10]. It investigated vaccination attitudes through several sections and had a response rate comparable to similar web-based surveys (~25%). [

23] The greatest strength of our survey compared to previous studies investigating vaccine status in IBD patients is the high number of respondents (n=1252). This represents one of the biggest IBD populations investigated both for their vaccination coverage and hesitancy. The high response rate is likely due to the concurrent investigation of hesitancy and the attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines when the vaccination campaign started in Italy. [

24]

In the future, vaccination status among the IBD population could be examined through national official records or in multicentre cohorts of patients. Such studies should carefully consider issues around patients’ privacy.

4.3. Vaccine Hesitancy

Many IBD patients may be hesitant towards vaccines because of concerns about the balance between safety and benefits of vaccination. According to the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), vaccine hesitancy is the term used to describe: “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services”. [

25] Attitude towards vaccination is affected by many factors including complacency, convenience and confidence. Many studies demonstrated that vaccine hesitancy is a common phenomenon globally, with variability in the rationale behind refusal of vaccine acceptance, including perceived risks and benefits, religious beliefs and lack of knowledge and awareness. [

25] Other factors associated with vaccine hesitancy include public health policies, social factors, previous experience, educational and income levels and the messages spread by the media. [

26]

The COVID-19 pandemic brought back to public debate the discussion around vaccine hesitancy because of some mass media misinformation and emphasis on the hypothetical side effects of vaccines including long-term side effects, toxicity of adjuvants and preservatives and the weakening of the immune system. [

27]

In our survey, however, 88.8% of the participants stated a positive attitude towards vaccination while only 3.9% of the respondents expressed a negative attitude towards vaccines. This is a very encouraging result as other studies investigating vaccine hesitancy among patients affected by chronic illnesses showed more negative attitudes [

23]. Comparable results were found between patients who use chronic immunosuppressive treatments and those ones who underwent liver transplantation. [

28]

Patients in our study stated that their positive attitude towards vaccinations was mainly influenced by the awareness of the potentially harmful opportunistic infections which could spread again with the decline of vaccination coverage rates. Unexpectedly, the attitude towards vaccination was not influenced by the immunosuppressive treatments.

Unfortunately, despite a general positive attitude towards vaccinations, our study showed that the vaccination coverage among IBD patients keeps on being suboptimal as previously shown in many pre-pandemic studies. [

7,

8,

9,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] There is often poor awareness of the importance of vaccines for IBD patients by patients themselves as well by gastroenterologists and general practitioners. [

29,

30]

Gastroenterologists are the primary HCPs for IBD patients, playing a key role in ensuring adequate disease management. Unfortunately, their knowledge on the correct use of vaccines is often insufficient [

29,

30,

31,

32] and they do not always provide adequate patient counselling [

8], as has emerged from specific surveys.

4.4. Possible Strategies to Improve Vaccination Coverage among Patients with IBD

Since the general poor attention towards the importance of vaccinations could be due both to general practitioners and IBD specialists, the best way in which physicians can be helped is by the provision of checklists expressly created to investigate patients’ vaccination coverage and vaccinations to be prescribed. Several guidelines suggest that patients’ vaccination status should be checked by physicians at the time of diagnosis. This is particularly the case for gastroenterologists who play a primary and pivotal role in the treatment of IBD patients. A vaccination plan should be defined before starting any immunosuppressive treatment. It is essential to keep on promoting and updating guidelines that provide specific indications on how to actively advocate for vaccination, particularly for those IBD patients who need immunosuppressive therapies. As some gastroenterologists think that the planning and administering of vaccines should be done by general practitioners, a good strategy to increase vaccination coverage among IBD patients could be improving the communication between these categories of health care providers.

Other strategies include the involvement of patients' associations in spreading a culture of vaccination, the implementation of awareness campaigns aimed at adolescents, young adults and adults, with the support of digital instruments, and the organization of specific vaccination events. Web-based surveys like this one could represent a good awareness instrument. Other web-based instruments like telemedicine could play an important role, in particular during pandemics. [

33]

For those patients with a greater probability of being hesitant against vaccines (e.g., complementary and alternative medicine users, patients with low education level) the best way to change their minds may be by optimizing patient-doctor communication. Finally, education and correct information still represent the best ways to improve vaccination coverage among IBD patients: even when an adequate level of awareness is present, messages and warnings from healthcare providers seem to be necessary.

5. Conclusions

The public debate around vaccinations is a trending topic. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first national post-pandemic survey to investigate coverage and attitudes towards general vaccinations among IBD patients.

Our study demonstrated that, despite a general positive attitude towards vaccinations mainly influenced by the awareness of possible return of opportunistic infections with the decline of vaccinations rates, there is still suboptimal vaccination coverage against VPDs in IBD patients.

This might suggest a possible role of physicians in under-prescribing vaccinations to this population, since most patients have a positive attitude. A minority of hesitant patients (3.9%) still remain to be convinced, primarily by enhanced patient-doctor communication.

The results of this survey could be a starting point for developing specific vaccination campaigns to increase vaccination rates against VPDs in IBD patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, File S1: The adapted version of the validated questionnaire.

Author Contributions

A.C. contributed to the conceptualization, writing, review, and editing; M.M. contributed to the writing; D.N. contributed to the analysis of data, review, M.A., A.A., F.B., F.F., F.M., G.M., A.O., L.P., S.R., F.R., A.T., N.B. contributed to the review and editing; S.L. contributed to the data acquisition, review and editing; C.C. contributed to the conceptualization, analysis of data, writing, review and editing; M.V. contributed to the conceptualization, review and editing, F.C. contributed to the review and editing, supervision.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—current research IRCCS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Scientific Advisory Board Ethics Committee of AMICI ETS. All the subjects received an email explaining the rationale of the study and the digital informed consent to participate and had to sign the digital informed consent before participating.

Informed Consent Statement

Written digital informed consent has been obtained from the patients to conduct this research and publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

AMICI ETS—Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell’Intestino. The anonymous native English speaker who revised the manuscript for language and style is acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

A.C. served as an advisory board member and/or received lecture grants from Alfasigma, Aurora, Bromatech, Janssen, Ferring, Mayloy-Spindler, Simbios, Takeda. FSM served as an advisory board member and/or received lecture grants from AbbVie, Biogen, Galapagos, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. A.A. consultant/advisory board: AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Ferring, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, and Takeda; speaker fees: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ferring, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nikkiso, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda; research funding: Merck, Pfizer, and Takeda. F.B. advisory board per biogen, Celgene, MSD, Takeda, and Janssen. A.O. received lecture grants and/or served as an advisory board member for: AbbVie, Chiesi, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Sofar, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. S.R. reports Janssen, and Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceuticals. C.C. reports Pfizer, MSD, GSK, Seqirus, and Sanofi-Pasteur. M.V. served as consultant to: Abbvie, MSD, Takeda, Janssen-Cilag, Celgene; he received lecturer fees from Abbvie, Ferring, Takeda, MSD, Janssen-Cilag, Zambon. F.C. served as consultant to: Mundipharma, Abbvie, MSD, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Celgene; he received lecture fees from Abbvie, Ferring, Takeda, Allergy Therapeutics, and Janssen and unrestricted research grants from Giuliani, Sofar, MS&D, Takeda, and Abbvie. The other authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Beaugerie, L.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toruner, M.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Harmsen, W.S.; et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharzik, T.; Ellul, P.; Greuter, T.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease [published correction appears in J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Aug 16;:]. J Crohns Colitis. 2021, 15, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winthrop, K.L.; Melmed, G.Y.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Herpes Zoster Infection in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Receiving Tofacitinib. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farraye, F.A.; Melmed, G.Y.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Kane, S.V. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease [published correction appears in Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul;112(7):1208]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults [published correction appears in Gut. 2021 Apr;70(4):1]. Gut. 2019, 68 (Suppl. 3), s1–s106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omar, H.A.; Sherif, H.M.; Mayet, A.Y. Vaccination status of patients using anti-TNF therapy and the physicians' behavior shaping the phenomenon: Mixed-methods approach. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.; Rumman, A.; Thanabalan, R.; et al. Vaccination in inflammatory bowel disease patients: attitudes, knowledge, and uptake. J Crohns Colitis. 2015, 9, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melmed, G.Y. Vaccination strategies for patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunomodulators and biologics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, G.; Costantino, C.; et al. ESCULAPIO working group. Information sources and knowledge on vaccination in a population from southern Italy: the ESCULAPIO project. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017, 13, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey by Momentive. Available online: https://it.surveymonkey.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; McGinley, E.L. Infection-related hospitalizations are associated with increased mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2013, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinsley, A.; Navabi, S.; Williams, E.D.; et al. Erratum to Increased Risk of Influenza and Influenza-Related Complications Among 140,480 Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Number 61, April 2005. Human papillomavirus. Obstet Gynecol. 2005, 105, 905–918. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Demers, A.A.; Nugent, Z.; Mahmud, S.M.; Kliewer, E.V.; Bernstein, C.N. Risk of cervical abnormalities in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based nested case-control study. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Khatibi, B.; Reddy, D. Higher incidence of abnormal Pap smears in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Lautenbach, E.; Lewis, J.D. Incidence and risk factors for herpes zoster among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006, 4, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthrop, K.L.; Melmed, G.Y.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Herpes Zoster Infection in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Receiving Tofacitinib. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oorschot, D.; Vroling, H.; Bunge, E.; Diaz-Decaro, J.; Curran, D.; Yawn, B. A systematic literature review of herpes zoster incidence worldwide. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021, 17, 1714–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Sekine, M.; Kudo, R.; Adachi, S.; Ueda, Y.; Miyagi, E.; Hara, M.; Hanley, S.; Enomoto, T. Differential misclassification between self-reported status and official HPV vaccination records in Japan: Implications for evaluating vaccine safety and effectiveness. Papillomavirus Res. 2018, 6, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Hubers, J.; Farraye, F.A.; Sampene, E.; Hayney, M.S.; Caldera, F. Accuracy of Self-Reported Vaccination Status in a Cohort of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2021, 66, 2935–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeardMann, C.A.; Smith, B.; Smith, T.C.; Wells, T.S.; Ryan, M.A. Millennium Cohort Study Team. Smallpox vaccination: Comparison of self-reported and electronic vaccine records in the millennium cohort study. Hum. Vaccines 2007, 3, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, A.; Michelon, M.; Roncoroni, L.; et al. Vaccination Status and Attitudes towards Vaccines in a Cohort of Patients with Celiac Disease. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, A.; Noviello, D.; Conforti, F.S.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness and Hesitancy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Analysis of Determinants in a National Survey of the Italian IBD Patients' Association. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. Vaccine misinformation and social media. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e258–e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Invernizzi, F.; Centorrino, E.; Vecchi, M.; Lampertico, P.; Donato, M.F. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Liver Transplant Recipients. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, S.K.; Calderwood, A.H.; Long, M.D.; Kappelman, M.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Farraye, F.A. Immunization rates and vaccine beliefs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an opportunity for improvement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaluso, F.S.; Mazzola, G.; Ventimiglia, M.; et al. Physicians' Knowledge and Application of Immunization Strategies in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Survey of the Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion 2020, 101, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, S.K.; Coukos, J.A.; Farraye, F.A. Vaccinating the inflammatory bowel disease patient: deficiencies in gastroenterologists knowledge. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 2536–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.H.; Goodman, K.J.; Fedorak, R.N. Inadequate knowledge of immunization guidelines: a missed opportunity for preventing infection in immunocompromised IBD patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, A.; Noviello, D.; Mazza, S.; Berté, R.; Caprioli, F.; Vecchi, M. Trust in telemedicine from IBD outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dig Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, lifestyle and clinical characteristics of the study population with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (n = 1252).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, lifestyle and clinical characteristics of the study population with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (n = 1252).

| Characteristics |

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

Title 1 |

Title 2 |

Title 3 |

| Gender |

1252 |

|

entry 1 |

data |

data |

| Male |

523 |

41.8 |

entry 2 |

data |

data 1

|

| Female |

729 |

58.2 |

|

|

|

| Age (years), mean (range) |

47.7 (37-58) |

|

|

|

|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

| Married/cohabitant/second marriage |

854 |

68.2 |

|

|

|

| Single/divorced/widowed |

398 |

31.8 |

|

|

|

| Educational level |

|

|

|

|

|

| Undergraduate |

778 |

62.1 |

|

|

|

| Graduate |

474 |

37.9 |

|

|

|

| Number of family members |

|

|

|

|

|

| <4 |

1205 |

96.2 |

|

|

|

| >4 |

47 |

3.8 |

|

|

|

| Children under 10 years of age |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1065 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

187 |

|

|

|

|

| Disease type |

|

|

|

|

|

| Crohn’s Disease |

614 |

49 |

|

|

|

| Ulcerative colitis |

612 |

48.9 |

|

|

|

| Indeterminate colitis |

26 |

2.1 |

|

|

|

| Adherence to therapy recommended for IBD |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

16 |

1.3 |

|

|

|

| Yes/Most of the time |

1236 |

98.7 |

|

|

|

| Therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

| None/mesalamine |

668 |

53.3 |

|

|

|

| Biologic or Immunosuppressive drug |

584 |

46.7 |

|

|

|

| Disease duration |

|

|

|

|

|

| <5 Years |

161 |

12.9 |

|

|

|

| >5 Years |

1091 |

87.1 |

|

|

|

| Working as healthcare professionals (HCPs) |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1100 |

87.9 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

152 |

12.1 |

|

|

|

| Adherence to other preventive activities (e.g., oncological screening) |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

355 |

28.4 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

897 |

71.6 |

|

|

|

| Alcohol intake |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

759 |

60.6 |

|

|

|

| Yes often/minimal consumption |

493 |

39.4 |

|

|

|

| Self-reported active lifestyle |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

670 |

53.5 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

582 |

46.5 |

|

|

|

| Smoking habit |

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-smoker |

899 |

71.8 |

|

|

|

| Smoker/former smoker |

353 |

28.2 |

|

|

|

| Use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1093 |

87.3 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

159 |

12.7 |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Reported previous vaccinations among the study population affected (n = 1252).

Table 2.

Reported previous vaccinations among the study population affected (n = 1252).

| Previous vaccines |

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

Title 1 |

Title 2 |

Title 3 |

| Tetanus |

928 |

74.1 |

entry 1 |

data |

data |

| HBV |

464 |

37.1 |

entry 2 |

data |

data 1

|

| HAV |

200 |

16 |

|

|

|

| MMR |

542 |

43.3 |

|

|

|

| Flu |

848 |

67.7 |

|

|

|

| Pneumococcus (PCV13 or PPSV23) |

364 |

29.1 |

|

|

|

| HPV |

95 |

7.6 |

|

|

|

| Meningitis |

250 |

20 |

|

|

|

| VZV |

192 |

15.3 |

|

|

|

| Patients vaccinated for some of the reported VPDs |

255 |

20.4 |

|

|

|

| Patients never vaccinated against the reported VPDs |

13 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Patients who did not remember previous vaccinations |

259 |

20.7 |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Attitudes towards vaccinations in the study population (n = 1252).

Table 3.

Attitudes towards vaccinations in the study population (n = 1252).

| Attitudes towards vaccinations |

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

Title 1 |

Title 2 |

Title 3 |

| Opposed to vaccinations |

49 |

3.9 |

entry 1 |

data |

data |

| Indifferent to vaccinations |

91 |

7.3 |

entry 2 |

data |

data 1

|

| In favour of vaccinations |

1112 |

88.8 |

|

|

|

| Willingness to be vaccinated in future (against COVID-19 and other diseases) |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

98 |

7.8 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

1154 |

92.2 |

|

|

|

| Willingness to vaccinate your children in future |

(938) |

|

|

|

|

| No |

24 |

2.6 |

|

|

|

| Yes, totally |

752 |

80.2 |

|

|

|

| Yes, partially |

162 |

17.2 |

|

|

|

| Possible return of VPDs with decline of vaccination coverage rates |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

160 |

12.8 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

1092 |

87.2 |

|

|

|

| Previous negative experience (personal/family members/relatives reported/referred) with vaccinations |

(1238) |

|

|

|

|

| No |

1075 |

86.8 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

163 |

13.2 |

|

|

|

| Best strategy to prevent VPDs |

|

|

|

|

|

| Vaccination |

624 |

49.8 |

|

|

|

| Other (diet, physical activity, homeopathy etc.) |

60 |

4.8 |

|

|

|

| Vaccination + other strategies |

568 |

45.4 |

|

|

|

| Main reason for vaccination adherence due to their IBD |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

796 |

63.6 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

456 |

36.4 |

|

|

|

| Higher confidence in HCPs in comparison with mass media on vaccine information |

(1227) |

|

|

|

|

| No |

51 |

4.2 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

1176 |

95.8 |

|

|

|

Table 4.

Crude OR and adjOR of factors associated with trust and positive attitude regarding vaccinations among patients with IBD enrolled in the study (n=1252).

Table 4.

Crude OR and adjOR of factors associated with trust and positive attitude regarding vaccinations among patients with IBD enrolled in the study (n=1252).

| |

Crude OR |

CI 95% |

p-value |

AdjOR |

CI 95% |

p-value |

Title 1 |

Title 2 |

Title 3 |

Title 4 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

entry 1 * |

data |

data |

data |

| - Male |

ref |

|

0.92 |

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| - Female |

0.98 |

(0.69 – 1.40) |

|

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| Age in years (continuous variable) |

0.99 |

(0.98 - 1.01) |

0.94 |

|

|

|

entry 2 |

data |

data |

data |

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| - single/divorced/widowed |

ref |

|

0.42 |

|

|

|

entry 3 |

data |

data |

data |

| - married or cohabitant |

0.95 |

(0.82– 1.08) |

|

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| Children under 10 years of age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| No |

ref |

|

0.69 |

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| Yes |

1.04 |

(0.87– 1.22) |

|

|

|

|

entry 4 |

data |

data |

data |

| Degree |

|

|

|

|

|

|

data |

data |

data |

| Under graduation |

ref |

|

<0.05 |

ref |

|

0.29 |

|

|

|

|

| Graduation |

1.59 |

(1.01– 2.53) |

|

1.38 |

(0.75 – 2.52) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Working as an healthcare professionals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

0.78 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

1.08 |

(0.63– 1.87) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Adherence to therapy recommended for IBD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

0.35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

2.58 |

(0.48 – 9.35) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smoking habit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

0.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

0.75 |

(0.51 – 1.09) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Physical activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

0.60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

0.91 |

(0.64– 1.29) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alcohol use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

0.21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

1.26 |

(0.88 – 1.81) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Use of homeopathic products, believe in alternative medicine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.01 |

ref |

|

0.27 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

0.48 |

(0.31 – 0.75) |

|

0.89 |

(0.67 – 1.18) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Adherence to other preventive activities (e.g., oncological screening) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.05 |

ref |

|

0.14 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

1.58 |

(1.09 – 2.28) |

|

1.43 |

(0.89 – 2.31) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Possible return of vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) with decline of vaccination coverage rates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.001 |

ref |

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

11.3 |

(7.64 – 16.9) |

|

5.67 |

(3.45 – 9.30) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Past negative experience (also reported/referred) with vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.001 |

ref |

|

0.16 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

0.26 |

(0.17 – 0.39) |

|

0.66 |

(0.36 – 1.18) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Main reason for vaccination adherence due to IBD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.001 |

ref |

|

0.053 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

3.43 |

(2.14 – 5.49) |

|

1.72 |

(0.99 – 2.97) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Higher confidence in HCPs in comparison with mass media on vaccine information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.001 |

ref |

|

0.07 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

3.30 |

(1.73 – 6.27) |

|

2.33 |

(0.93 – 5.81) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Immunosuppressive therapies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

ref |

|

<0.029 |

ref |

|

0.179 |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

2.18 |

(1.07-3.79) |

|

1.35 |

(0.74-4.75) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).