1. Introduction

Governments around the world have committed themselves to supporting the transformation towards more sustainable societies, endorsing transformative goals such as responsible consumption and production, the eradication of poverty, and clean and affordable energy for all (see

https://sdgs.un.org/goals). While transformations have also occurred in the past, the urgency associated with current social-ecological transformations is unprecedented. Here, we develop a novel transformation approach that both conceptualizes and nurtures transformative change through attention to multiple value creation and institutional change.

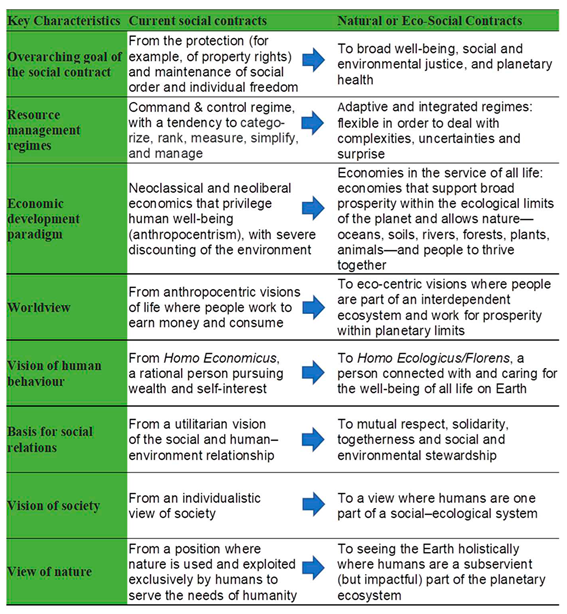

Our main argument is that transformative change towards sustainability (for instance, in the energy or food system and in making the economy more regenerative and fair) needs a society-wide approach. Importantly, realizing transformative change requires new Natural Social Contracts or Eco-Social Contracts (Huntjens, 2021; Huntjens and Kemp, 2022; UNRISD, 2022; Gough, 2022; Bogert et al. 2022; Kempf & Hujo, 2022; Krause et al. 2022). We define Natural Social Contracts or Eco-Social Contracts as the collective power of societies, people and nature for dealing with the polycrisis of the 21st century (including deepening inequalities and ecological crises) through collective agreements (at multiple governance levels) among members of a society to cooperate with one another and abide by certain rules or norms targeted at sustainability, equity and justice, with the associated rights and duties of care for the environment and the well-being of others (including future generations and all life on this planet). This involves adopting a different worldview (eco-centric or Earth-centric instead of anthropocentric), a different view of humanity (homo ecologicus/florens instead of homo economicus), and different economies and cultures (regenerative/post-growth/wellbeing economies and cultures instead of linear ones). Social contracts are different in each country and context; but essentially, they comprise the web of relationships that bind together disparate citizens, communities, institutions and governments into a just and sustainable society (Mohamed and Huntjens, 2023). Reimagining social contracts requires a reconfiguration of not only the overarching goal of a social contract, but also a fundamental restructuring of how humanity views itself and its relationship with nature (Mohammed & Huntjens, 2023). Given that ‘current’ social contracts, with their emphasis on economic growth, extractivism, human domination, global markets etc., are strongly associated with the current planetary crises, the development of new social contracts is urgently needed.

Table 1 provides an overview of the key characteristics of the underlying paradigm shift and transformation from current to new Natural or Eco-Social Contracts. This new discourse is nurtured and disseminated in the Global Research and Action Network for a New Eco-Social Contract established in 2021, coordinated by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) and the Green Economy Coalition (GEC), and with more than 350 participating organizations joining in the first two years. The network reflects the plurality of perspectives that are part of the ongoing visioning and implementation processes for new social contracts at various levels and different contexts.

The transformation to new social contracts appears an Herculean task, since any transformation is up to formidable barriers: i) no actor has the overview and power to do this, ii) transformative change entails the deliberate decline of certain arrangements and hence comes with disadvantages and costs for important actors, some of which will actively resist it (Rosenbloom and Rinscheid, 2020), iii) transformations are values-laden and entail conflict about the legitimacy of technologies, policies and practices (Geels and Verhees, 2011), iv) new system practices are not born perfect and their diffusion depends on their improvement and changes in the socio-economic context.

Due to lock-in effects along various dimensions (behavioral, technological, institutional; see Seto et al. 2016), most actors cannot change currently unsustainable practices, beliefs and dispositions as acts of free will (Kemp and van Lente, 2023). However, they can be enrolled in processes of transformative change if the outcomes of such processes are attractive for them. Making the outcomes attractive is a key challenge for transformative governance and requires the availability of different pathways to give actors a choice. In this paper, we will outline how the transformation flower approach and its focus on projected futures, visions of multiple value creation and required institutions, all of which are subject to change, can contribute to achieving transformative change. We develop our approach to support the formulation of acceleration agendas for context-specific transition pathways as well as society-wide transformations. We therefore aim to provide an answer to the following core question: How can positive transformative change be achieved through a society-wide transformation approach?

To demonstrate how our approach can be fruitfully applied, we use the case of the Dutch food system transformation. We chose this case due to our involvement in the National Research Program Transition to a Sustainable Food System (NWA-TDV) in the Netherlands, in particular focusing on the governance of food system transformation. We will thereby illustrate how our phase model, the TFA, may be used along four phases of enacting transformative change (described in section 4), drawing on theoretical building blocks that will be described in section 2.

To provide some context for our empirical illustration, critical reviews of the agri-food system (e.g. NewForesight and Commonland 2017; Godfray et al. 2010; SAPEA 2020, Huntjens, 2021, Aarts and Leeuwis, 2023) speak to the need for fundamental change, or a transformation, to a sustainable, healthy and just system. The current system is characterized by a dominant focus on production and efficiency, producing as much food per square meter as possible at the lowest possible cost for the producer, thereby compromising sustainability, justice and healthfulness. Moreover, value creation is limited to financial profit maximization and cost driven development (Huntjens, 2021). Technology (e.g. pesticides and artificial fertilizer) is used to make natural ‘production factors’ (i.e. water, soil, plants and animals) manageable in order to match a low cost price within an international competitive trade model. The predominant focus on productivity and profit maximization in ‘free markets’ has shifted social and ecological values along with justice concerns to the background (Huntjens, 2021). Profit is narrowly defined in monetary terms by externalizing ecological and social costs for humans and non-humans, which means these ‘hidden costs’ are usually not reflected in the price of food (ibid). A recent estimate puts the ‘hidden costs’ of global food and land-use systems at $12 trillion, which is 20% more than its market value of $10 trillion (Pharo et al. 2019). These figures only deal with production, but exclude the suffering endured by animals in animal agriculture, or the costs related to unsustainable and unhealthy food environments and consumption, the disconnection between industrial farmers and food consumers, and other social-economic costs.

Two broad trajectories have been established for limiting the negative effects of current agricultural production systems. The first one is based on agroecology, organic farming and local resourcing. This movement is linked with alternative conceptions of the economy (Vivero-Pol, 2017). The second is primarily based on technological fixes based on the premise of ‘sustainable intensification’. We do not take sides in the sense of advocating for any of these models. In our view, a crucial challenge is to provide farmers with the resources required to ensure that agricultural production will benefit society and the natural environment (potentially in multiple ways), while terminating practices that may be profitable in the short term but are clearly detrimental from a socio-ecological and long-term perspective. As we will explain, this requires cross-sectoral, long-term oriented and transdisciplinary governance and collaboration that allow for continuous learning and reflection. It requires interactive processes that bring together different actors, interests and perspectives, allow for shared problem definitions and narratives of change, and identify joint intervention strategies and an instituted process that deals with resistance and the accommodation of interests.

2. Transformative Change: Conceptual Building Blocks from the Social Sciences

2.1. Transformations and Governance

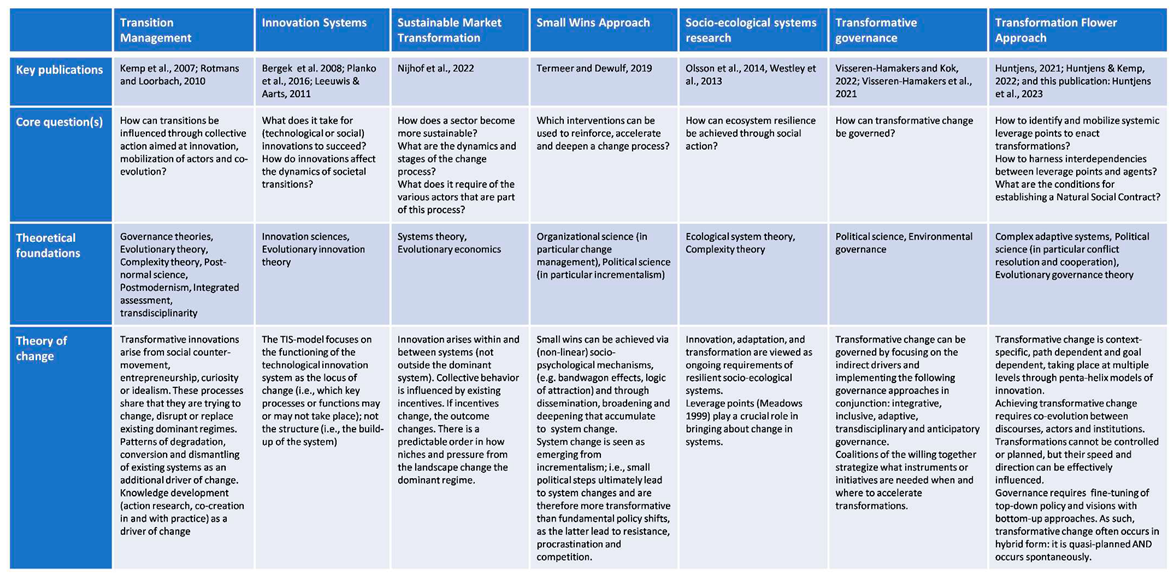

In the literature on sustainability transition and socio-ecological transformation, various steering approaches have been proposed. To varying degrees, these provide inspiration for the development of the TFA introduced in more detail in section 4. A particularly prominent approach is transition management, used in the Netherlands as a governance approach for system innovation. Transition management seeks to enroll business in a process of change towards more environmentally sustainable systems that require collective actions and programmes for achieving this (Kemp et al. 2007, Rotmans and Loorbach, 2010). The steering philosophy is

guided evolution, taking the form of active support for transition paths and transition experiments and selection pressures on unsustainable technologies. Transition management is based on the notion that persistent problems require fundamental changes in societal subsystems, which are best worked towards in a forward-looking and adaptive manner, based on multiple pathways to more ecologically sound systems of production and consumption (Kemp, 2010). Transition management shares several elements with the literatures on technological innovation systems (Bergek et al. 2008) and sustainable market transformation (Nijhof et al., 2022; see

Table 2), such as the emphasis on evolutionary change and an appreciation of the behavior of complex adaptive systems. It goes beyond these approaches, however, in its strong focus on governance interventions and modulation of the interplay of innovation and societal change.

Transition management continues to receive a lot of attention in academia and practice. It has been praised for focusing on the transformation of systems of production and the attention to pathways (Meadowcroft, 2009). Criticisms have been raised with respect to (1) its rather functionalist and technocratic character and the inherent democratic deficit (Hendriks, 2008), (2) the fact that the state is typically portrayed as a progressive and collaborative “facilitator-stimulator-controller-director” of the transition management process (Lawhon and Murphy, 2011), (3) a rather tenuous articulation of how socio-technical change is interacting with economic structures, cultural change and changing state-business-civil society relations (Feola, 2020; Kemp et al., 2020), (4) the missing attention to ecological gains and distributional consequences (for instance in developing countries; Wigboldus et al. 2021), and (5) the weak grasp on the politics of societal learning and the contextual embedding of policy design (Voss et al. 2009; Meadowcroft, 2011).

One overarching criticism of transition management is that the politics of complex system change are sidelined due to the over-emphasis on the problem-solving element of governance. Accordingly, transition management tends to neglect that powerful actors are able to mobilise societal support against interventions aimed at system change (Aarts & Leeuwis, 2023). A necessary condition for achieving system change is thus to attenuate the agency of actors resistant to ecologically desirable changes – be it by winning their support, changing institutional rules, or making them accept changes in regulations or market rules. As foreshadowed in the last column of

Table 2 and developed further below, we explicitly address this issue in our TFA, which aims at making transformative changes desirable and feasible for the beneficiaries of the current system, with a view on enhancing their capacity for change. With due attention to joint values and principles such as responsibility, resilience and ecological effectiveness and sensitivity to concerns about a ‘just transition’, different actors can be enrolled into processes of change.

Importantly, in contrast to other transformative approaches, our approach de-emphasizes forced change. Instead, it conceives change as involving multiple pathways. It thereby takes up insights from the Small Wins approach (Termeer and Dewulf, 2019), which emphasizes the merits of incremental changes. Incrementalism may not only avoid resistance, procrastination and competition, but also lead to transformation via an accumulation of potentially non-linear shifts.

Achieving transformative change also requires addressing the underlying paradigms, values, worldviews and principles (of current and future desirable systems) as indirect systems drivers (Huntjens, 2021; Huntjens and Kemp, 2022). Addressing these drivers is challenging because changes in worldviews and values are typically slow and protracted processes. Transformative governance theory (Visseren-Hamakers et al., 2021) offers five principles that are helpful for confronting these drivers: (1) building governance mixes that address cross-cutting challenges in an integrative way (across sectors, governance levels and places); (2) empowerment of weaker and marginalized voices; (3) adaptive decision-making (to harness feedback and recalibrate if necessary); (4) recognition of different knowledge systems and supporting the inclusion of sustainable and equitable values by focusing on types of knowledge that are currently underrepresented; and (5) application of the precautionary principle when governing for uncertain future developments, especially the development or use of new technologies (Visseren-Hamakers and Kok, 2022; Visseren-Hamakers et al., 2021). We endorse these principles of transformative governance theory and build on them in the development of the transformation flower methodology.

2.2. Dealing with Power

To identify leverage points for transformation pathways, it is vital to engage with the politics of transformations (Meadowcroft 2011); notably: what interests are at stake, how is political power distributed in a society and how is it exercised, what changes in power relations are needed to enable transformations and how can those be enabled, and what may coalitions for transformative change look like?

Questions of politics and power are a central theme of social science analyses of systems stability and change and have also received some attention in food systems transformation research (Clapp and Fuchs 2009; Cohen and Ilieva 2015; Hinrichs 2014; Karlsson et al. 2018). Given that politics—the activities and (often conflictual) processes surrounding the adoption or rejection of policy—are ultimately the result of power relations, we focus particularly on power. Rather than providing a comprehensive review of conceptualizations, we focus on established approaches to power that can be mobilized fruitfully in the context of our ambition.

According to Dahl (1957, p. 202), power is the capacity to make others do something they would not otherwise have done. This understanding, which is open to a variety of ways in which this capacity translates into outcomes (e.g., through coercion or persuasion), can be helpful in analyzing politics in situations of open contestation. But often, power plays out more subtly. For instance, powerful actors might exploit power asymmetries to prevent issues or solutions from appearing on the political agenda (Bachrach and Baratz 1962; Schattschneider 1960), and less powerful actors might choose not to participate in political struggles given their weak position (Pierson 2016). Power also entails ideational dimensions, manifested through the use of language and semiotics to sway the perceptions, cognitions and preferences of other actors (Lukes 2005, p. 28). Power, hence, becomes apparent in discursive interactions, in which actors strategically represent problems and possibilities in such a way that they shape decisions about future states perceived as viable and desirable (Levy and Egan 1998; Rosenbloom 2018; Smith et al. 2005). Seen in this light, power in food system transformations is closely interlinked with the ability to convince others of alternative visions of desirable future states of the system and its role in society.

A fundamental problem for steering societal processes is that those who are in charge of the steering wheel are at the same time part of systems they wish to steer. Dialogic webs, which have become an important governance mechanism since the 1980s, have been shown to be preferred by most economic actors across sectors, as they open opportunities for businesses to exercise ideational and persuasive power (Braithwaite and Drahos 2000). At the same time, such dialogic webs also provide potentially untapped opportunities for less powerful actors to work towards shifts both in dominant conceptualizations of problems and societal values and norms more broadly, if they succeed in the creation of “shared meanings and collective identities” (Fligstein and McAdam 2012, p. 46). Based on the webs of influence approach, Gunningham (2019), for instance, examines the effects of environmental activists on climate change governance. Despite being confronted with massive power imbalances and collective action problems, environmental movements or even single activists can become influential catalysts for transformation if they succeed in forming and navigating (e.g. when deciding which allies to invite when and where) webs of influence with a diverse range of actors, some of which are endowed with ‘hard’ power resources. When it comes to the food system, this means that even under conditions of massive power asymmetries between actors, change agents may be able to trigger cascades of transformative change as part of broader webs of influence.

2.3. Leverage Points

In order to propose powerful interventions that can transform deep-seated properties, behaviors and outcomes of systems of production and consumption, the identification of leverage points is a crucial analytical step. Leverage points are ‘places within a complex system […] where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything’ (Meadows, 1999, p. 1). This idea of leverage points is very appealing to external decision makers, but begs a diagnostic analysis and leverage point actions that are agreed upon and implemented. Application of the leverage points concept allows for a scientific unraveling of system complexity, which is needed to address root causes of unsustainable food systems.

An insightful visualization for identifying system leverage points has been constructed by Maani and Cavana (2007), building on the iceberg analogy of complex systems that consist of different levels (Meadows, 2008). It suggests that the most powerful transformative interventions are targeted at the deeper levels of the food system iceberg, in particular the mental models at the bottom that capture broader societal values, principles, assumptions and beliefs that shape our systems. Importantly, leverage points for food system transformation may be located in other systems often not accounted for when studying agri-food systems, such as the financial or energy sector, or in society-wide factors, such as the organization of our global economy. These cross-sector interactions highlight that transformative governance requires an integrative approach (Huntjens et al., 2012; Visseren-Hamakers and Kok, 2022). The TFA, which we introduce in section 4, incorporates the identification of leverage points as one of its key steps to analyze and propose transformative interventions for sustainable food systems. Our approach extends the model of Meadows (1997) in giving attention to bottlenecks and signals for distinctive pathways. Bottlenecks are “forces that sit between other phenomena and may gatekeep potential change” and signals are “highly connected elements” that serve as “lead measures for changes happening less visibly/more slowly elsewhere in the system” (Murphy, 2022, p. 10). We view mental models and paradigm shifts as strongly dependent on other changes (such as attractive transactions for the actors concerned) and avoid pitfalls of idealism, reductionism and pure pragmatism.

2.4. Values for Transformative Change

While the role of values has been widely acknowledged as potential drivers of transformative change (Horlings 2015), sustainability scientists have not yet put values at the center of scholarly attention (Miller et al. 2014). In psychological research, values are conceptualised as standards or principles that motivate and guide people’s judgments, decisions and behaviours. People’s judgments about good or bad, worth striving for or avoiding, justified or illegitimate depend on the values they prioritise (Schwartz 1992). The weight individuals assign to certain values (e.g., biospheric values like respecting the earth) determines the extent to which they develop specific beliefs about valued objects or beings and environmental norms, which in turn, if activated, shape environmentally relevant behaviours (Harland et al. 1999; Schwartz 1977). The fact that individuals differ in the ways in which they resolve trade-offs between different values helps to explain divergence in human behaviours (Schwartz 1992).

While psychological research focuses on individual human beings as “value holders”, research in cognitive anthropology and organisational studies examines values at the level of social groups, in particular organisations. Along these lines, values not only capture individual cognitive structures but also “collective social structures” (d’Andrade 2008). This distinction is highly relevant, as transformations involve the decisions of numerous organisational actors representing different backgrounds and interests. In the food system, for instance, the unsustainable system of food provision and consumption is upheld by dominant value orientations not only among individuals but also among many organisational actors that legitimize a focus on maximum production, efficiency, competition, market-driven allocation, and commodification of nature and animals. We argue that understanding the potential role of values in driving transformative change requires a sense of the interplay of personal and organisational values (Finegan 2000; Vandenberghe and Peiro 1999) and system values (McGreevy et al. 2022), with a particular focus on identifying the political and institutional factors that shape organisational or system values and on creating contexts conducive to activating transformative values.

The environmental values literature highlights that while analysing the prevalence of broad values among actors is important, understanding how certain contexts condition the activation of values in specific situations and their manifestation as more specific beliefs and norms may be even more relevant, especially when it comes to assessing the importance of values in driving system transformation (Horlings 2015; Tadaki et al. 2017; Te Velde et al. 2002). For instance, in a context where vegan food is cheap and superior in taste and texture to non-vegan alternatives, and plant-based lifestyles are promoted in an appealing way by celebrities or through other social institutions, individuals with strong hedonic value dispositions may engage in pro-environmental behaviour (a vegan diet) precisely because conditions make such a decision pleasurable and convenient (Miller et al. 2014; Steg 2016). Absent such conditions, pro-vegan beliefs and norms are much less likely to be developed by the same individuals. Hence, values cannot be separated from the environment and social processes in which they become activated and possibly also reshaped. Values are dynamic and often constrained by or traded off against one another or other drivers of behavior depending on context (Davis et al. 2023, in press).

Behavioural change thus depends on attractive practices (which are doable, affordable and attractive to the actors concerned), which in turn depend on coordinated actions to create those and changes in the (political and socio-economic) landscape. Along these lines, the principle of circularity and basic forms of animal well-being developed from nice but nonbinding aspirations to widespread norms, putting pressure on those not adhering to them yet. These developments may cause governments to set minimal standards and upgrade these over time. Latent values may thus become manifest values through alternative practices and institutions. This example also highlights that values and principles are interrelated with business practices and logics, policy and politics. Going one step further, we believe that an approach focusing on multiple value creation, a concept that understands values as an outcome of economic processes, holds great value for achieving change and effective cooperation (Miller et al. 2014). For instance, if farmers engage in the provision of ecosystem services (because they get paid for this), they not only diversify the range of socio-economic values they generate, but likely also shift their prioritization of ecosystem services in terms of values-as-standards and, in addition, may influence others to do the same. Farmers may also engage in energy production and tourism, as alternative sources of income, and be helped by government and other stakeholders to achieve this. Attention to multiple value creation helps to break the gridlock of efficiency via scale-economies.

Value change is an emergent outcome of transformations. Accepting responsibility for nature regeneration and lowering the environmental footprint of one’s actions depends on attractive ways to do so, which in turn depend on collective action and changes in incentives. Finding a common value base among actors and the use of attractive imaginaries for innovation and development may offer opportunities to steer a system into the desired direction. The IPBES Values Assessment Report (2022) finds that there are a number of broadly shared values that can be aligned with sustainability, emphasizing principles like unity, responsibility, stewardship, and justice towards other people, non-human animals and other parts of nature. According to the report, four values-centered leverage points can help create the conditions for transformative change towards more sustainable and just futures: (1) Recognizing the diverse values of nature; (2) Embedding valuation into decision-making; (3) Reforming policies and regulations to internalize nature’s values; (4) Shifting underlying societal norms and goals to align with global sustainability and justice objectives.

4. The Transformation Flower Approach

The Transformation Flower Approach (TFA) offers an analytical device for researchers and a hands-on tool for practitioners. It is a society-wide transformation approach to support the development of collective agreements and acceleration agendas (at multiple governance levels) targeted at a sustainable, equitable and just society. It serves the purpose of creating new social contracts with a more important role for duties of care and responsibility (Huntjens and Kemp, 2022). In the literature, these are referred to as a Natural Social Contracts (Huntjens, 2021; Huntjens and Kemp, 2022; Huntjens et al., 2023) or Eco-Social Contracts (Gough, 2022; Kempf and Hujo, 2022; Kempf, Hujo and Ponte, 2022; Krause et al. 2022; UNRISD 2022; Mohamed and Huntjens, 2023). The TFA has been adopted as a theory of change by the IPBES Transformation Change Assessment (2022-2024) for linking options, levers and actors for transformative change/pathways.

A preliminary version of the transformation flower was first published by Huntjens and Kemp (2022). Predecessors and related approaches have been used in environmental governance, diplomacy and mediation processes in various parts of the world, as well as for studying transformation processes and institutional change in water resources management, agriculture, and spatial planning (Wijnen et al., 2012; Huntjens et al. 2014, 2016; Yasuda et al., 2017; 2018; Islam and Madani, 2017; Huntjens, 2017, 2019, 2021). The TFA has been further developed with a view to clarify links to (and differences vis-à-vis) other transformative change approaches (see

Table 1). Moreover, based on insights gained during application, the approach has been continuously improved and refined further. In particular, the TFA has been applied in the research project ‘Transition to a Sustainable Food System’ in the Netherlands (2021-2024, funded by the Dutch Research Agenda, NWA) and in the IPBES Transformative Change Assessment (2022-2024) to develop and substantiate acceleration agendas for specific transformative pathways. This dialogue between theoretical work and application has enabled an ongoing iterative learning process. While the TFA discussed here presents a robust and validated approach, we anticipate further developments in the future.

In

Figure 1 we provide an overview on the different dimensions of the TFA, which are translated to phases when using the TFA as a transformative tool. The TFA can hence be used as a step-by-step approach to identify options for transformative change, multiple value creation and effective cooperation through connecting actor coalitions and interdependent systemic leverage points. The starting point of applying the TFA is set by defining context-specific and goal-dependent transformation paths (Huntjens and Kemp, 2022). By giving attention to the recursive relationship between practices and systems, leverage points for transformative change can be identified. From there, the transformation flower can be used as a ’plug and play’ tool for individual steps or combinations thereof within the TFA, varying from short-cycle knowledge development (including co-creation and brainstorming sessions, sandpits and Crutzen workshops) to long-term cyclical knowledge development (including multi-year transdisciplinary research in living lab-like settings). A short-cycle trajectory can be part of a medium or long-cycle trajectory. This offers a wide range of possible applications:

Vision development for a specific area or transformative pathway.

Identification of leverage points and actors involved, taking into account interdependencies and non-linear feedback loops.

Organization and steering of collective action & transformation agendas based on (priority) leverage points and including related actors/coalitions.

Identification of coupling opportunities, for example nexus solutions for water, climate, energy, food, nature and health.

Collective system analysis or systemic co-design, for example focusing on value orientations, coherence between system interventions and options for multiple value creation.

Political-economic analysis and understanding of power dynamics in order to inform strategic positioning and options for effective cooperation.

Monitoring, evaluation and adjustment of the transformation process. This can be based on (1) qualitative methods, such as reflexive monitoring, dynamic learning agendas or field notes, or (2) quantitative metrics, such as Key Performance Indicators or composite indicators for each dimension (petal) of the transformation flower, or (3) combinations thereof.

Social and transformative learning within a transformative learning environment.

Broad stakeholder participation and transdisciplinary collaboration, e.g. through multi-stakeholder workshops for systemic co-design, are an essential part of the TFA-methodology, with the aim to engage and involve relevant stakeholders as early as possible in the process of developing collective outputs. Depending on several factors, such as synchronization with ongoing processes, the workshops could be organized at various moments, and more specifically to collect stakeholder input for several phases in the TFA. As such, a TFA multi-stakeholder workshop allows for a participatory assessment regarding the following core questions:

- a)

What are important leverage points and related actors or coalitions?

- b)

What are possible connections (win-win, coupling opportunities and/or trade-offs) between these leverage points?

- c)

What are priorities (i.e. leverage points with (expected) high transformative impact) and related time-scale?

- d)

Which actors to involve & to join forces?

- e)

Collective agreement on action agenda, strategy and/or implementation plan

By attending to these questions, the TFA connects agency with structure, as a necessary step to determine the power to influence, and to find options for actor coalitions to realize transformative change. In the remaining part of this section, we provide an explanation and illustrations of the various phases of the TFA, based on the application of the approach to the transformation of the Dutch food system.

Phase 1: Clarifying the transformation arena

The initial phase of the TFA proceeds from identifying the transformation arena. The notion of pathways is central in this context. Here we use the definition of pathways that is also applied in the IPBES Values Assessment (IPBES, 2022, p. 405), where a pathway to transformation is defined as a strategy for getting to a desired future based on a recognizable body of sustainability thinking and practice, driven by an identifiable coalition of actors. This understanding also asserts that each transformation pathway is context-specific and goal-dependent, with an aspiration to break-away from path-dependencies. Examples of contextual factors include the nature and extent of the societal change in question, the history of cooperation (or the lack thereof) between the parties involved, and the key biophysical, material, and socio-economic features of the area or pathway in question (Huntjens, 2019, 2021).

Transformation pathways are used to work towards desired futures. The TFA asserts that both incumbents and challengers should be involved in the formulation and implementation of these pathways, in an effort to exploit every possible opportunity for changes in a forward-looking way. Such collaboratively developed transformation pathways help to escape the gridlock of incumbent-dominated systems for which there are no perfectly developed alternatives in the short term. A transformative change process from system A to system B may involve a bundle of technologies, practices, resources and organisations. As such, it may need to accommodate a plurality of perspectives, visions, and theories in order to help achieving more buy-in and mitigating resistance to change. While some paths might be dominated by challengers and others by incumbents, power balances are dynamic, which makes them subject to agency (i.e., the ability to exert influence, see Ali-Khan and Mulvihill 2008; Newman and Dale 2005) and social skills. To avoid the peril of ‘capture’ by incumbents that have no serious interest in transformative change and ensure that transformative pathways do not end up by merely tinkering at the margins, it is important that actor coalitions for transformative change strategically build webs of influence and employ ideational power in an effort to gain the upper hand in legitimacy struggles (Markard et al. 2021).

During the first phase, we suggest to use the X-curve model (Loorbach, 2014, and modified by authors, see

Figure 2) as a heuristic device to define the transformation arena along with an assessment of visions, values and goals based on the following guiding questions: (1) What needs to change in the current system, and (2) What needs to stop? While these two questions proceed from the current (often implicit) social contract (represented by the downward curve emerging from “system A” in the X-curve framework), two complementary questions attend to transformative visions and innovations (represented by the upward curve): (3) What needs to grow towards achieving a new Natural Social contract, and (4) What does a future perceived as desirable (or “system B”) look like? In the following, as an illustration of how this framework may be applied to the development of transformative pathways, we summarize how discussions surrounding the Dutch food system transformation may be usefully structured around these four questions and in line with the goals of phase 1 of the TFA.

First, what needs to change? We proceed from the observation that study after study makes clear that current food consumption and production patterns exacerbate a number of urgent sustainability challenges in the areas of health and well-being of humans, non-human animals, and the planet. The Dutch agri-food sector has traditionally focused on production and efficiency, producing as much food per square meter as possible at the lowest possible cost and with a limited appreciation of value creation (Huntjens, 2019, 2021). Given a low willingness among consumers to increase expenditures for food, the food industry relies on highly efficient, low-lost production methods, providing few incentives to invest in sustainability measures and true cost pricing. This economic logic leads to a vicious circle. The predominant focus on productivity and profit maximization in ‘free’ global markets has shifted social and ecological costs and values into the background (ibid). Profit is narrowly defined in monetary terms by externalizing ecological and social costs, which means these ‘hidden costs’ are usually not reflected in the price of food (ibid). As a bottom line, the entire agri-food system has to change in order to ensure a sustainable, healthy and just future, both at the level of its materiality (current systems of provision and consumption) and in terms of its interwoven ideational and economic underpinnings.

Second, what needs to stop? Recent research in the area of social-ecological transformations has highlighted the need to actively govern the termination of unsustainable configurations (Koretsky, Stegmaier, Turnheim, and van Lente, 2023; Rinscheid et al. 2021; van Oers, Feola, Moors, and Runhaar, 2021). Along these lines, food system practices that are detrimental to soil and water quality and the wellbeing of humans, plants, animals and planetary ecosystems, such as harmful pesticides, may need to be phased out in a timely manner. Beyond technologies and practices, the targets of such interventions also include economic incentives and structures that foster the treadmill of production.

Third, what needs to grow? The current food system can be made more sustainable through wider adoption of nature-inclusive agriculture, short food supply chains, agroecology, sustainable and circular (high-tech) horticulture and animal husbandry, in which emissions are captured and turned into valuable products. At the same time, there is a need to shift diets towards plant-based substitutes, given the high environmental impacts of meat and dairy products and non-human animal suffering. Farmers may also widen their activities, including farm-based tourism and the provision of ecosystem services for which they are rewarded. Transformative change in this direction can be promoted by policies at the national and regional level. Moreover, there are opportunities for harnessing multi-system interactions and integrating various sectoral transformational pathways into a more or less integrated approach, for examples involving improved water management, renewable energies and closing material loops (Huntjens, 2021; Rosenbloom, 2020). The Greenport West-Holland initiative, for instance, tries to achieve a more sustainable horticultural system in combination with renewable energy generation, the closing of material loops (e.g. water, plastics and biomass) and shorter food supply chains. While far from complete, this illustration shows that there is much more to transforming food systems than production, kilograms, and certification (Huntjens, 2019, 2021).

Finally, what is a desirable future? Answering this question requires an assessment of values, norms, transformative goals and visions among stakeholders. This involves examining which values and norms held by individuals and organizations may collide with each other, and which ones are shared and could therefore be the basis for encouraging collective action. As argued in section 2.3, a useful assessment of values would attend to the specific empirical context under examination and be tailored to identifying transformational visions shared by actors in order to help carving out transformative pathways. In this sense, the identification of a shared value base in a multi-stakeholder process serves the purpose of developing a transformative vision and related transformative goals for a specific area or pathway.

The TFA is strongly linked to emerging new social contract theories, the principles of which are shown in

Figure 3. Accordingly, it goes beyond achieving material goals and seeks to make all stakeholders part of better pathways of change.

Phase 2: Linking options, levers and actors for transformative pathways

Phase 2 aims at achieving three objectives: (a) a multi-level stakeholder assessment, (b) identification of leverage points, and (c) coupling opportunities.

Phase 2a involves the identification of key stakeholders, referring to “all persons, groups, and organizations with an interest in the societal development in question, either because they are affected or because they can influence its outcome. This may include individual citizens and businesses, interest groups, government agencies, experts and the media” (cf. Huntjens, 2021). It is important to map the interests, incentives, and access to financial, personal, or institutional resources of all stakeholders who participate in the transformation arena. In addition, existing coalitions and partnerships need to be taken into account, since they can influence power dynamics. In order to better understand cooperation and decision-making, it will often be necessary to identify the preferred or dominant negotiation and influence strategies of each actor, as this information, when bundled, will provide greater insight into the role and influence of each individual actor (ibid).

Phase 2b involves the identification of leverage points. These leverage points are places in a complex system where a small change could bring about major changes (Meadows 2008). Some of these leverage points may be found in the underlying, often taken-for-granted structures of the system – e.g., dominant principles or mental models. Targeting such leverage points carries the promise of a broad transformative impact on the system. Identifying leverage points alone is not enough, however. System change also requires a good insight into the interrelationships of system elements and dynamics, for example, via (non-linear) feedback loops, and how desired outcomes can be achieved with maximum synergy effects and minimal ‘trade-offs’ (Kennedy et al. 2018). Adopting a systems-based approach helps recognize synergies and trade-offs, moving beyond linear towards more circular, inclusive systems (cf. SAPEA 2020).

The TFA facilitates the identification of leverage points for the six dimensions laid out in the flower (see

Figure 1). We suggest using literature reviews and/or interviews to identify leverage points for each dimension, along with obstacles and opportunities for transformative pathways. To support collating such information, we have developed and tested a matrix that includes key questions for each dimension of the Transformation Flower. The key questions were derived from the principles and possible leverage points shown in

Figure 3, but are formulated in an open way to provide a semi-open questionnaire that avoids bias as much as possible (see supplementary materials).

In search of leverage points, our own data collection process of the Dutch case entails an extensive content analysis of academic papers, reports from both NGOs and government bodies, news articles, and interviews with relevant actors.

Figure 4 provides a synthesis of key leverage points and options for transformative change in the Dutch food system derived from our application of Phase 2b of the TFA. As such, the result is considered an essential building block of a transformation acceleration agenda for the Dutch food system. It relies on four transformation pathways: (1) Nature-inclusive and circular agriculture, (2) Short food supply chains, (3) Circular horticulture in the Greenport West-Holland, and (4) the Protein Transition. The detailed findings are included in the supplementary materials

Going beyond their identification, we acknowledge that interdependencies between leverage points exist. Phase 2c is hence concerned with finding coupling opportunities to inform transformational agendas. This exercise involves identifying not only interdependencies between leverage points, but also the interests and abilities of actors with respect to these leverage points along with structural constraints and opportunities for chain reactions (positive feedbacks). We also propose that during this phase, a prioritization of key leverage points should be conducted, for example by determining which leverage points can be expected to have the most far-reaching impact in realizing the transformative goals in question. We provide an example of a prioritization of leverage points and related actors and coalitions as well as interdependencies with other leverage points in

Table 3.

It is important to bear in mind that most leverage points will depend on specific processes or circumstances, such as legislative processes, time sequences, market forces or consumer behavior.

Phase 3: Actor-specific transformation flowers and opportunities for multiple value creation and effective cooperation

Phase 3 is geared toward the following two outputs: (a) actor-specific transformation flowers, and (b) identifying options for multiple value creation and effective cooperation. The TFA thereby supports stakeholders in enhancing strategic alignment of policies and of business practices and institutional work, and in finding coupling opportunities to embark on a transformative pathway.

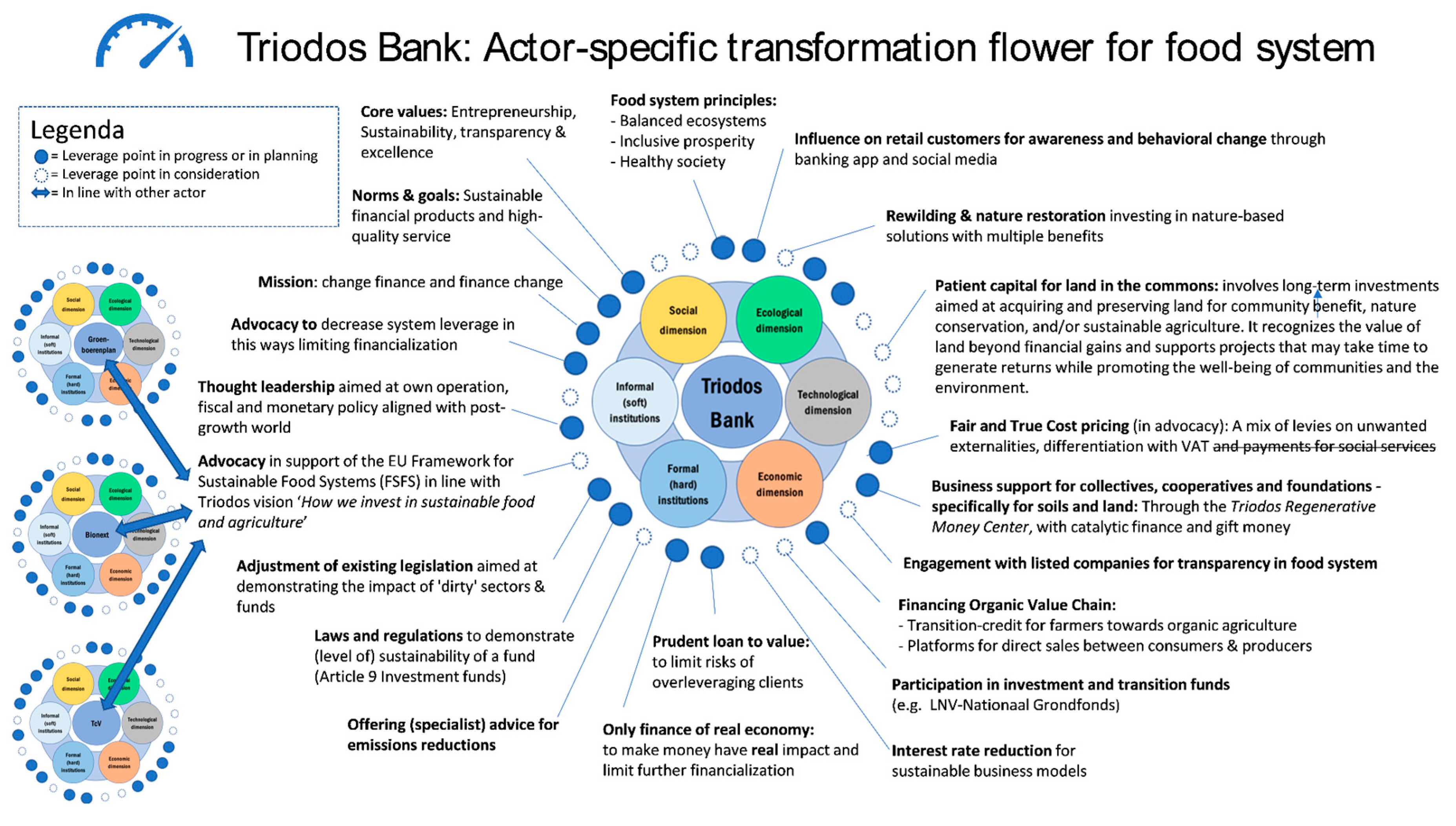

Complementing the systemic perspective taken in Phase 2, we propose to support and empower specific actors with a tailor-made transformation flower that provides an actor-specific overview of leverage points. For any individual actor, it is necessary to identify which leverage points are being implemented or targeted, as part of their influence strategy, and which leverage points are considered as an option, resulting in an actor-specific transformation agenda (see example in

Figure 5). Some actors may have different roles, ambitions or influencing mechanisms per leverage point. This differentiation per actor is an important addition to standard stakeholder analysis, because an actor can play different roles on different systemic leverage points. This information may also provide additional insight for the actor itself in order to support or strengthen its policy coherence, course of action or effective cooperation with others.

The allocation of key variables to specific actors is also relevant for indicating whether all relevant parties support a specific transformative pathway. As part of this analysis, it may turn out that some parties that could potentially play a relevant role are not yet involved.

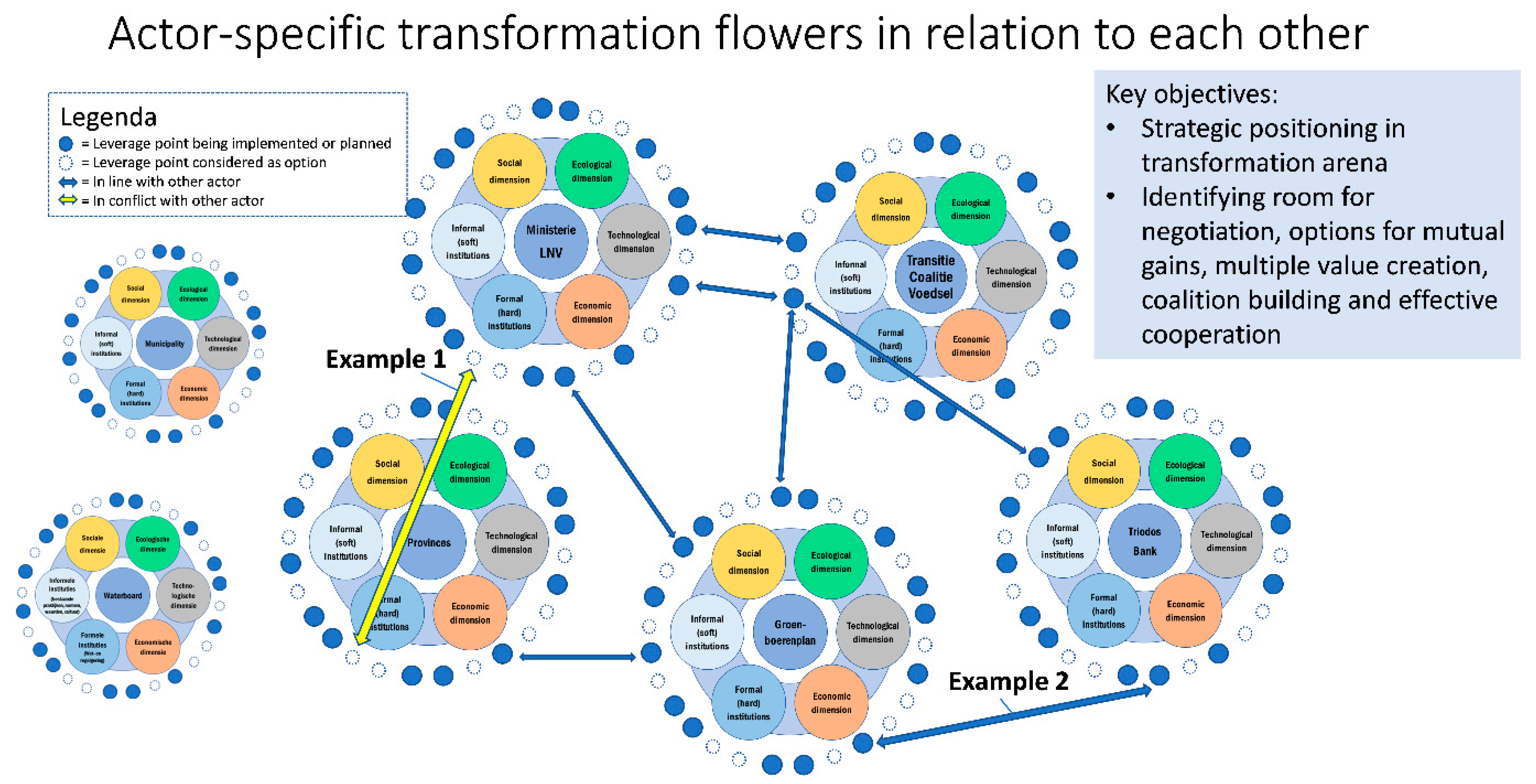

In addition to a regular stakeholder analysis, this phase will zoom in on how different actors relate to each other and how they influence the transformation pathway, thereby offering a novel method of power mapping and political economy analysis. This method takes the actor-specific transformation flowers (see example in

Figure 5) as key inputs, and compares them on similarities and differences. Our first assumption is that actors with a high level of similarity on leverage points, values, transition goals and vision will cooperate more easily, while actors with a high level of difference are less inclined to cooperate. Our second assumption is that more effective cooperation can be realized by coalition(s) of parties that offer complementarity in agency (i.e. the power to influence), for example by means of human capital, knowledge, technology, financial resources, or access to political and administrative networks. A legal mandate or the support of a large constituency can also be reasons to seek cooperation if one of the parties does not have this at its disposal, but is working on the same transformative goal(s). Our third assumption is that some tensions cannot be resolved and contestation is part of transformation. To only aim for consensus is not transformative at all, especially if current power relations are repeated in a multistakeholder setting. Paying attention to the quality of the conversations in which negotiations take place is therefore key, not to reach consensus, but to know the various perspectives, including the logics behind them and the power dynamics that are at stake.

A visual representation of this type of power mapping is shown in

Figure 6, including two examples of leverage points that are shared with other actors (see corresponding numbers): 1) a political difference between actors, in this case requiring negotiation to resolve the conflict, and 2) a similarity between actors with different agency, and thus providing an opportunity for effective collaboration.

Phase 4: Negotiation, transformative learning and dialogue

Clearly, the transformation of the food system depends on collaboration between stakeholders with different backgrounds and interests, which means that negotiations have to take place.

The distinction between distributive and integrative negotiations is insightful (Pruitt and Carnevale, 1993). Distributive negotiations start from the idea that there is a cake and it has to be divided. When one person gets more, the other gets less. A distributive negotiation is typically characterized by 1) over-questioning, hoping to get somewhere in the middle, 2) silent about own interests, and 3) no concern for the other. Whereas a distributive negotiating style is common in market relations it does not yield much in negotiations on the transformation of the current food system (Aarts and Van Woerkum, 1999). Negotiations will then have to take place in a different way: instead of dividing the cake, a new cake is baked, in which joint decisions are taken on the ingredients, the baking process and the intended result. An integrative negotiation is characterized by 1) concern for the other from the perspective that negotiation is only successful if all parties involved consider so, and 2) joint investigation of facts and values that is agreed upon by parties involved and that serves as a basis for next steps to be taken jointly. Integrative negotiation is difficult, precisely because it has to be applied in complex situations where interests are fundamentally different and often conflicting. Research shows that people quickly dig into their positions, of which they then try to convince the other (see for example Lems et al, 2013; Van Herzele en Aarts, 2013; Van Herzele et al, 2015; Bleijenberg et al, 2018).

An integrative negotiation style places high demands on the quality of the conversation. Such conversation should take the form of a dialogue. Other than in a discussion of a debate there are no opponents and no winners in a dialogue (Bohm, 1990). All participants and their input are respected, also if they think in fundamentally different ways. The aim of a dialogue is to explore and understand the differences between dissenters, and then to arrive at a common idea, a shared value, a collective conclusion. Dialogue is a connecting concept: despite major differences, a dialogue makes it possible to continue to communicate effectively.

This can lead to a change in old ways of thinking and to the emergence of new, shared perspectives, but that is not necessarily the case. Dialogue is about creating sufficient common ground to develop perspectives and activities that are shared by all parties concerned. An overlapping consensus (Rawls, 1971) is sufficient to arrive at a jointly chosen trajectory, without the parties involved having to beforehand give up their own ideas and identities, but instead explore what conditions are needed to stay involved. Obviously, such dialogues will need to be facilitated by professional boundary-spanners (Aarts, 2018).

The mutual gains approach is highly valuable in situations where two or more people are negotiating to reach an agreement that may be of benefit to both or all of them (Consensus Building Institute 2014). The MGA-approach lays out different steps for negotiating better outcomes while protecting relationships and reputation. “In the search for mutual gains, participants are encouraged to explore more ways to create more value (i.e. to increase the pie) and generate a broader vision on sharing benefits. To illustrate, whenever action is taken to remedy environmental problems, the benefits also cascade: for instance, nurturing wildlife and flora in a wetland can also reduce water pollution and soil erosion, and protect crops against storm damage, alleviating water scarcity and allowing sustainable food production” (cf. Huntjens, 2021).

The development of a context-specific agenda for transformative change is only one step in longer trajectories of co-creation and collective action. In this regard, transformation requires iterative learning cycles of monitoring, evaluation and transformative learning, which usually require longer trajectories of co-creation with sufficient time for reflexive monitoring, evaluation of interventions, and translating those lessons into a new cycle of ‘plan-do-evaluate-respond’ (Huntjens, 2021). This provides a foundation for reflection and social learning, while at the same time supporting accountability and an adaptive approach to deal with ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty, including unforeseen political or economic developments.

Transformative capacities can be strengthened through the strategic design of transformative learning spaces (Moore et al., 2018). Transformative learning can constitute a deep leverage point for a variety of actors for systemic change (Richardson et al., 2020).

Besides transformative learning, complex interaction effects are made a point of attention and scrutinisation. Social practice theory suggests that ‘group behaviour is shaped by a combination of cultural norms and habits, rules and regulations, modes of provision, and infrastructures that together determine the ways in which people behave’ (cf. Strengers and Maller 2014).

Actors often have implicit understanding of such interaction effects and possibilities for achieving systemic change. In this regard, we highlight the power of storytelling and narratives of change. When combining the strengths of stories—for instance about sustainability heroes—with that of system’s thinking it provides a powerful approach for transformative learning (e.g. see Tyler and Swartz 2012), and the application of complexity thinking in all social-ecological systems (Huntjens, 2021). This combination of storytelling and system thinking in order to facilitate transformative learning and institutional change is known in literature as ‘Narratives of Change’ (Krauß et al. 2018; Wittmayer et al. 2019; Huntjens, 2021).