Submitted:

23 July 2023

Posted:

24 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

| ID | Forecasting model | Year | Country | Forecast Horizon | Ref | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network (LSTM-RNN) | 2022 | USA | day ahead | [14] | 48.29 kW | 11.6 % | ||

| 2 | K-Nearest Patterns in Time Series (KNPTS) | 2021 | Spain | day ahead | [15] | 277.94 kW | |||

| 3 | Particle Swarm Optimization and Artificial Neural Network | 2021 | Germany | 15 min ahead | [16] | 1565 ± 150 kW | |||

| 4 | Transfer Learning +LSTM + BiGAN | 2020 | China | 15 min ahead | [17] | 0.003985 kW | 5.09 % | 0.942 | |

| 5 | Wolf-inspired optimization support vector regression (WIO-SVR) | 2022 | Vietnam | day ahead | [18] | 2.49 kWh | 6.25 kWh | 6.96 % | 0.98 |

| 6 | Multivariate CNN | 2021 | USA | month ahead | [19] | 1271.65 MW | 27.86 MW | 1.62 % | 0.92 |

| 7 | Multivariate Empirical Mode Decomposition (MEMD) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) with parameters optimized by Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | 2022 | China | day ahead | [20] | 113.9876 MW | 0.7866 % | 0.9542 | |

| 8 | Multi-temporal-spatial-scale Temporal Convolution Network (MTCN) | 2021 | China | day ahead | [21] | 119.2 kW | 79.4 kW | 1.89 % | 0.988 |

| 9 | A GAN-Enhanced Ensemble Model for Energy Consumption Forecasting in Large Commercial Buildings | 2021 | Korea | 10 min ahead | [22] | 1.39 | 0.81 | 0.98 | |

| 10 | CNN+Stacked+BiLSTM | 2021 | Korea | day ahead | [23] | 0.35 Wh | 0.31 Wh | 0.78 % |

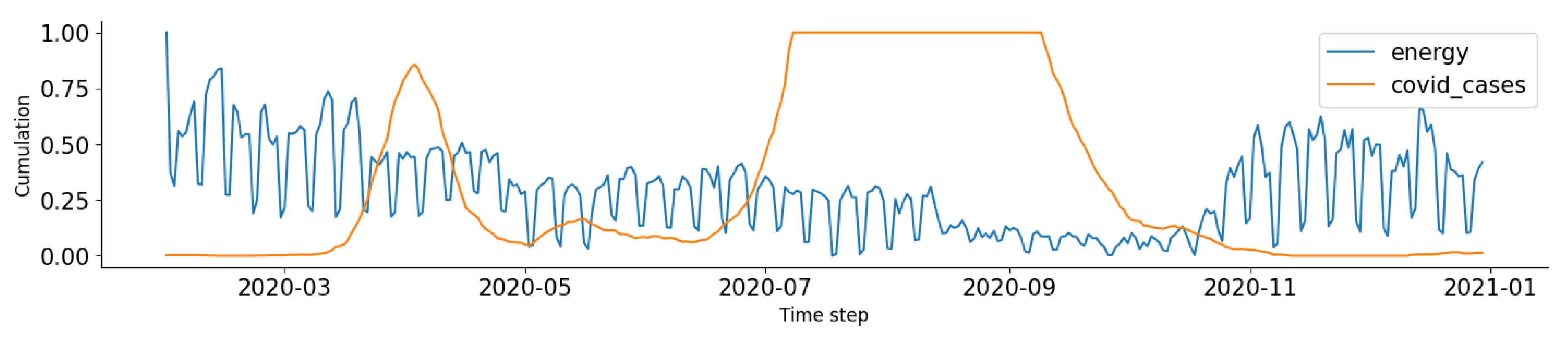

3. Data Used in This Study

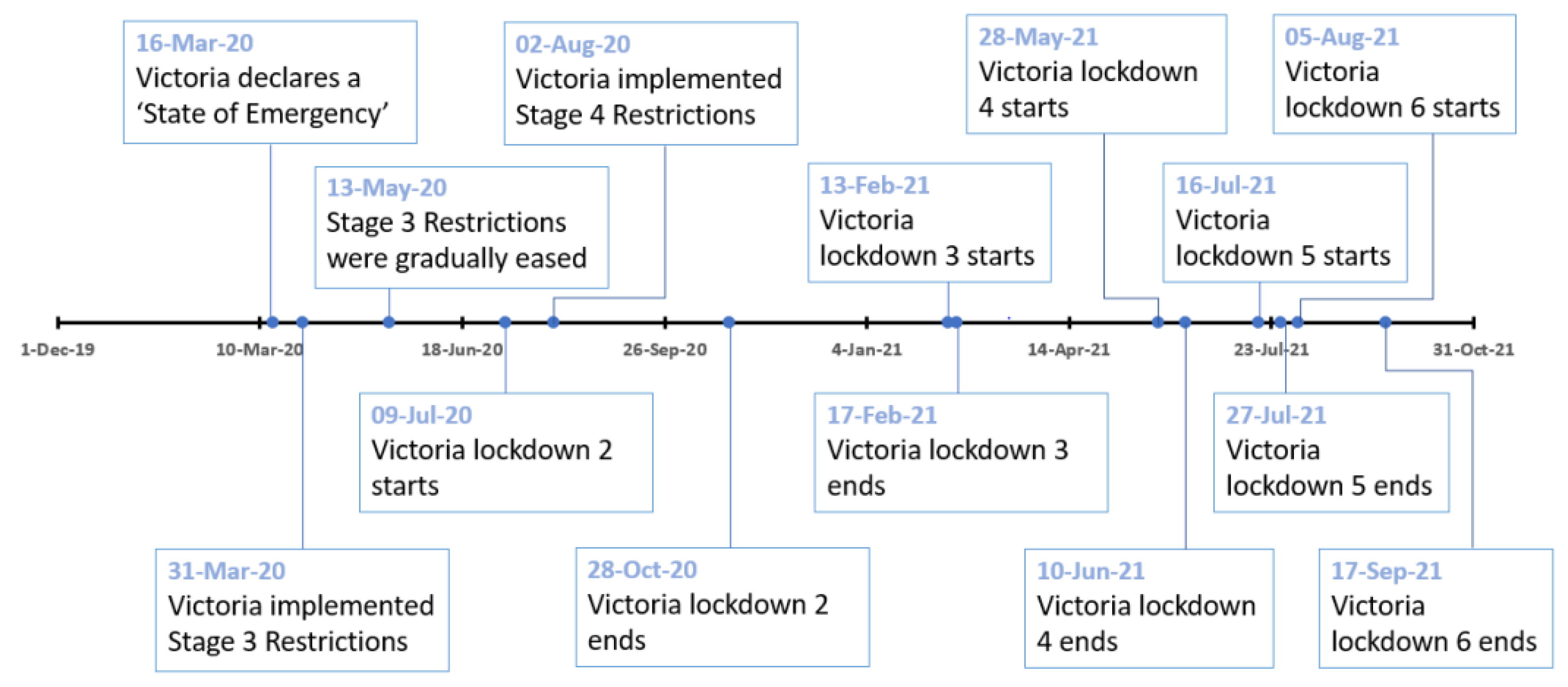

3.1. Daily COVID-19 Cases in Victoria

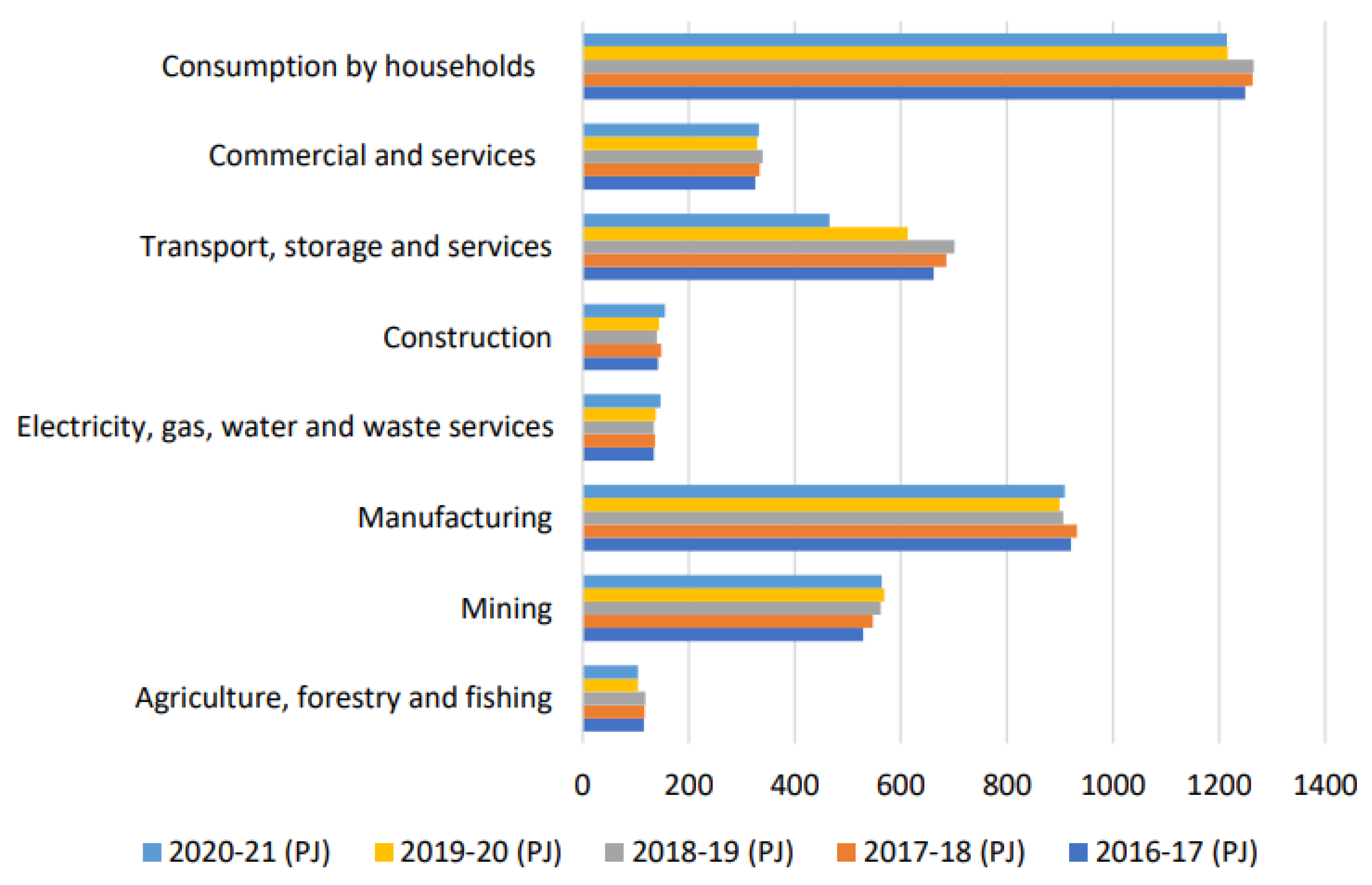

3.2. Impact of COVID-19 on Australian Higher Education

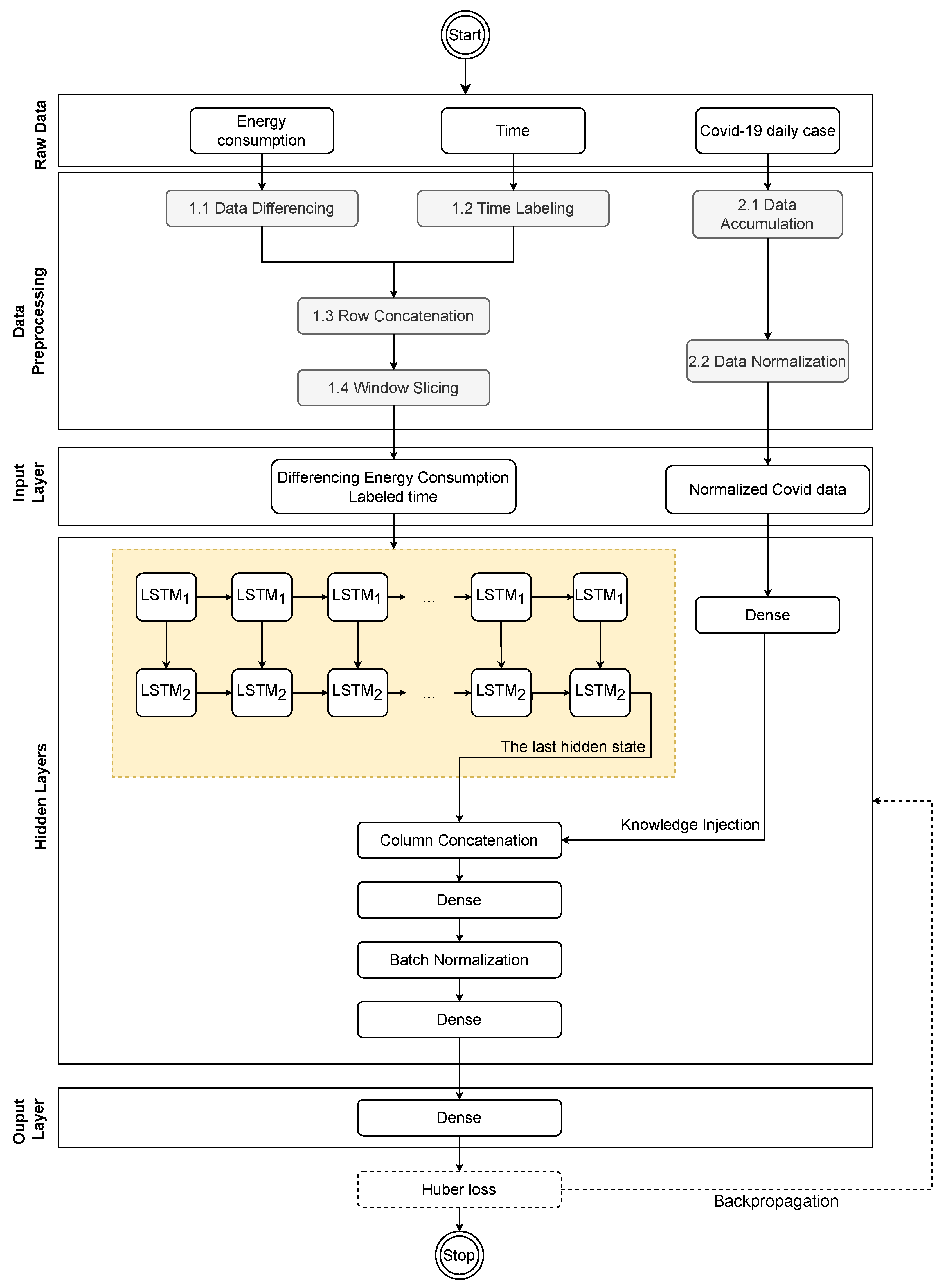

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Preprocessing

4.2. Forecasting Model

5. Experiment

5.1. Data

5.2. Baseline Model

5.3. Metric

5.3.1. MAPE

5.3.2. NRMSE

5.3.3. Score

5.4. Result

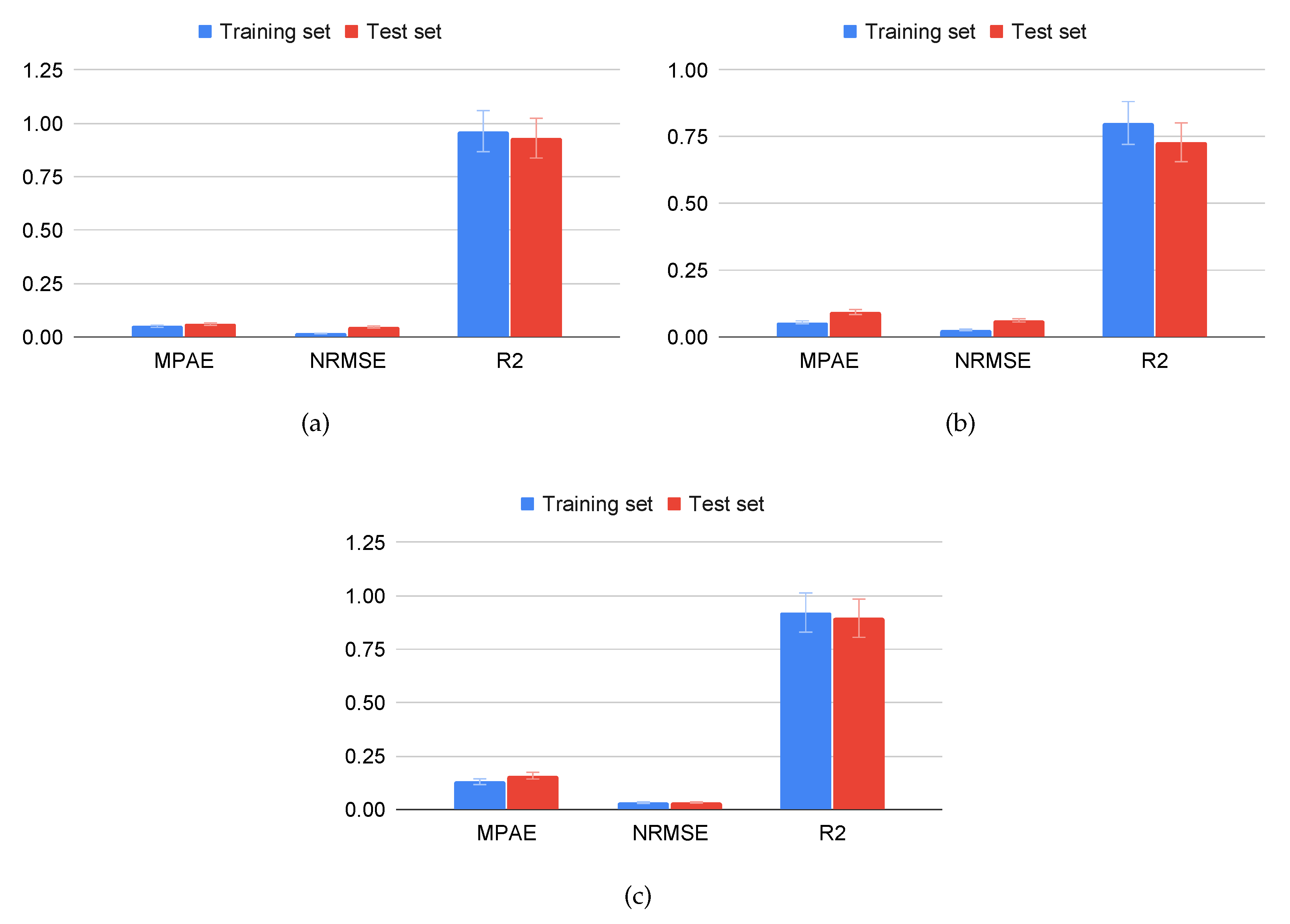

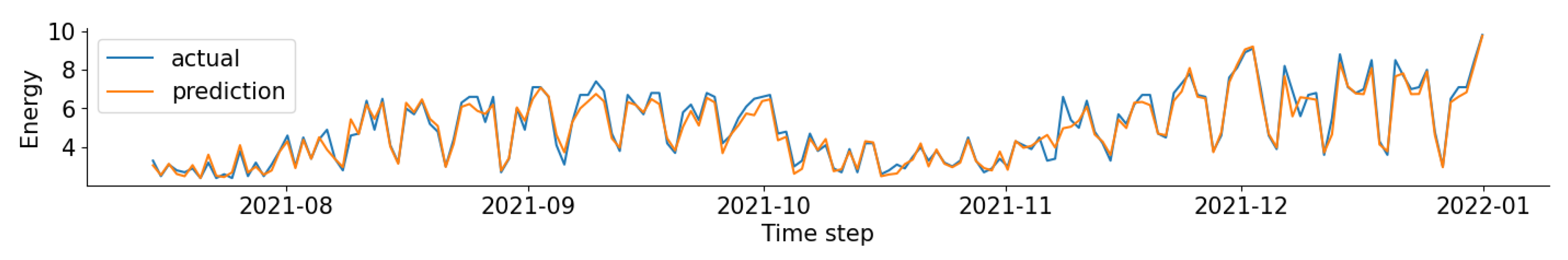

5.4.1. Performance of the Proposed Model on the Training and Test Sets

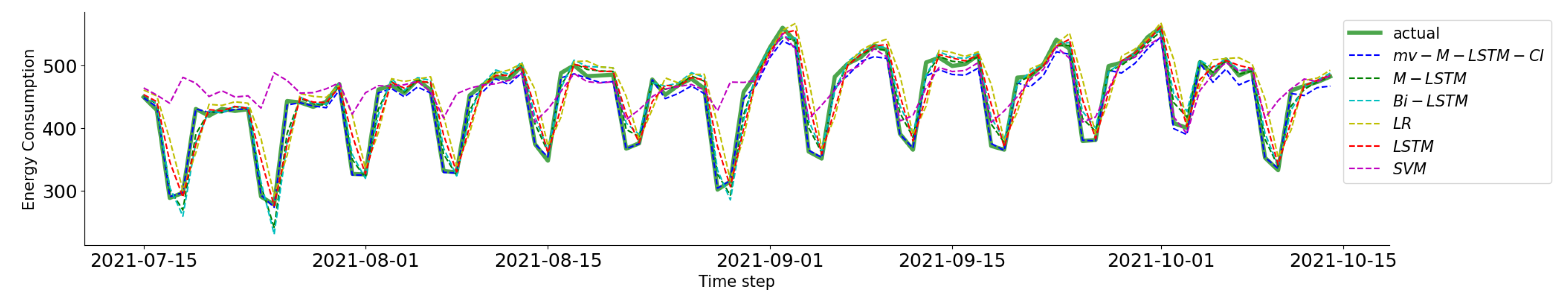

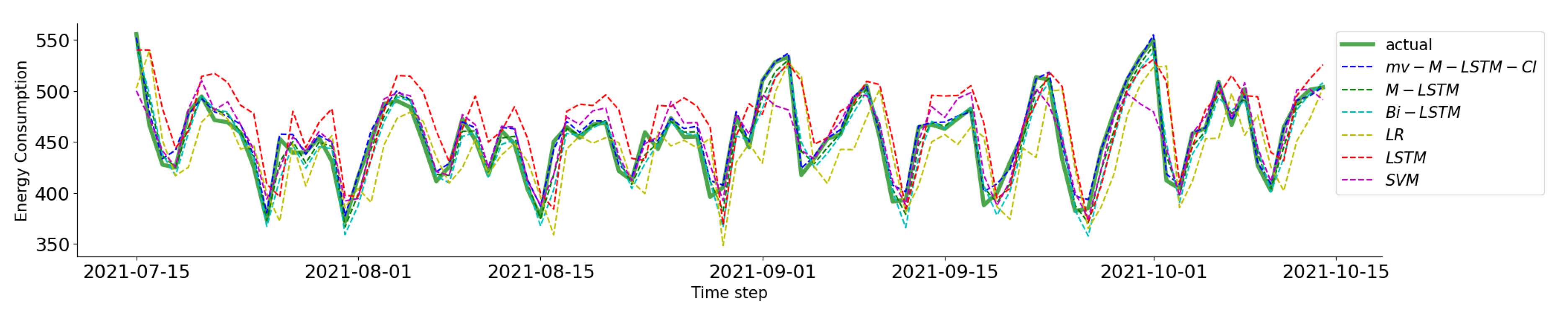

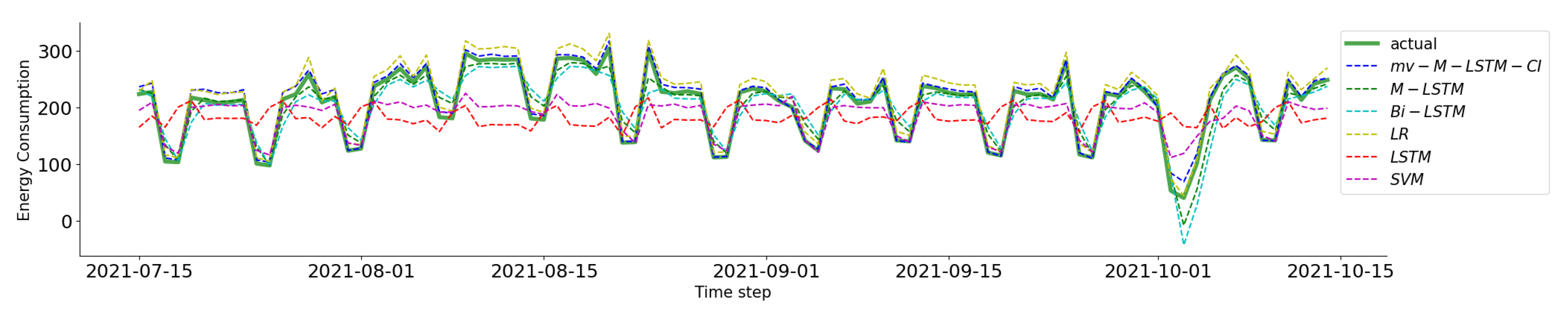

5.4.2. Comparison

6. Conclusion

References

- Year-on-year change in weekly electricity demand, weather corrected, in selected countries, January- December 2020 – Charts – Data Statistics - IEA — iea.org. (https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/year-on-year-change-in-weekly-electricity-demand-weather-corrected-in-selected-countries-january-december-2020?fbclid=IwAR0dN3dOAKFw85WuJr0bFJyTeOseC6U9kWfVSSuWZZT8I3sQUAkVdC2tQ), Accessed 03 Jul 2023.

- I. H. Panhwar, K. Ahmed, M. Seyedmahmoudian, A. Stojcevski, B. Horan, S. Mekhilef, A. Aslam, and M. Asghar. Mitigating power fluctuations for energy storage in wind energy conversion system using supercapacitors. IEEE Access. 8 pp. 189, 747–189, 760 (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. S. Thirunavukkarasu, M. Seyedmahmoudian, E. Jamei, B. Horan, S. Mekhilef, and A. Stojcevski. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—a review. Energy Strategy Reviews. 43 p. 100899 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023, Energy Account, Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023. (https://www.aer.gov.au/wholesale-markets/wholesale-statistics/annual-generation-capacity-and-peak-demand-nem), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Santiago, I., Moreno-Munoz, A., Quintero-Jiménez, P., Garcia-Torres, F. & Gonzalez-Redondo, M. Electricity demand during pandemic times: The case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy Policy. 148 pp. 111964 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Alasali, F., Nusair, K., Alhmoud, L. & Zarour, E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Electricity Demand and Load Forecasting. Sustainability. 13 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H., Tan, Z., He, Y., Xie, L. & Kang, C. Implications of COVID-19 for the electricity industry: A comprehensive review. CSEE Journal Of Power And Energy Systems. 6, 489-495 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sinden, G. Characteristics of the UK wind resource: Long-term patterns and relationship to electricity demand. Energy Policy. 35, 112-127 (2007).

- Rosenberg, E., Lind, A. & Espegren, K. The impact of future energy demand on renewable energy production – Case of Norway. Energy. 61 pp. 419-431 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N., Zarazua de Rubens, G., Choupanpiesheh, S. & Enevoldsen, P. When pandemics impact economies and climate change: Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on oil and electricity demand in China. Energy Research & Social Science. 68 pp. 101654 (2020).

- Bedi, J. & Toshniwal, D. Deep learning framework to forecast electricity demand. Applied Energy. 238 pp. 1312-1326 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Klemeš, J., Fan, Y. & Jiang, P. The energy and environmental footprints of COVID-19 fighting measures – PPE, disinfection, supply chains. Energy. 211 pp. 118701 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Ma, X. & Ma, M. A hybrid multi-objective optimizer-based model for daily electricity demand prediction considering COVID-19. Energy. 219 pp. 119568 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Haque, A. & Rahman, S. Short-term electrical load forecasting through heuristic configuration of regularized deep neural network. Applied Soft Computing. 122 pp. 108877 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Omella, M., Esnaola-Gonzalez, I., Ferreiro, S. & Sierra, B. k-Nearest patterns for electrical demand forecasting in residential and small commercial buildings. Energy And Buildings. 253 pp. 111396 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Brucke, K., Arens, S., Telle, J., Steens, T., Hanke, B., Maydell, K. & Agert, C. A non-intrusive load monitoring approach for very short-term power predictions in commercial buildings. Applied Energy. 292 pp. 116860 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D., Ma, S., Hao, J., Han, D., Huang, D., Yan, S. & Li, T. An electricity load forecasting model for Integrated Energy System based on BiGAN and transfer learning. Energy Reports. 6 pp. 3446-3461 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ngo, N., Truong, T., Truong, N., Pham, A., Huynh, N., Pham, T. & Pham, V. Proposing a hybrid metaheuristic optimization algorithm and machine learning model for energy use forecast in non-residential buildings. Scientific Reports. 12, 1065 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B. & Rabelo, L. A deep learning approach for peak load forecasting: A case study on panama. Energies. 14, 3039 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Hasan, N., Deng, C. & Bao, Y. Multivariate empirical mode decomposition based hybrid model for day-ahead peak load forecasting. Energy. 239 pp. 122245 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Yin, L. & Xie, J. Multi-temporal-spatial-scale temporal convolution network for short-term load forecasting of power systems. Applied Energy. 283 pp. 116328 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Hur, K. & Xiao, Z. A GAN-enhanced ensemble model for energy consumption forecasting in large commercial buildings. IEEE Access. 9 pp. 158820-158830 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M., Kwon, S. & Others Short-term energy forecasting framework using an ensemble deep learning approach. IEEE Access. 9 pp. 94262-94271 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Timeline of Every Victoria Lockdown (Dates & Restrictions), bigaustraliabucketlist 2021. (https://bigaustraliabucketlist.com/victoria-lockdowns-dates-restrictions/), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- State Of Emergency Declared In Victoria Over COVID-19, Premier of Victoria 2020. (https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/state-emergency-declared-victoria-over-covid-19), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- COVID-19 Update | 7 July 2020, National Retail Association 2020. (https://www.nra.net.au/covid-19-update-7-july-2020).

- Coronavirus: What changes under Melbourne’s Stage 4 restrictions, 9NEWS 2020. (https://www.9news.com.au/national/coronavirus-melbourne-stage-4-restrictions-explained-curfews-lockdown-what-is-open-closed-changes-covid19/652ee0f9-cc22-41df-b465-9a765a45c496), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Statement From The Premier, Premier of Victoria 2021. (https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/statement-premier-92), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- COVID LOCKDOWN: Victoria announces major restrictions to combat coronavirus outbreak, 7NEWS 2021. (https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/covid-lockdown-victoria-announces-major-restrictions-to-combat-coronavirus-outbreak-c-2148043), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Extended Lockdown And Stronger Borders To Keep Us Safe, Premier of Victoria 2021. (https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/extended-lockdown-and-stronger-borders-keep-us-safe), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Seven Day Lockdown To Keep Victorians Safe, Premier of Victoria 2021. (https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/seven-day-lockdown-keep-victorians-safe), Accessed 17 May 2023.

- International student numbers by country, by state and territory. (https://www.education.gov.au/international-education-data-and-research/international-student-numbers-country-state-and-territory), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- More than 17,000 jobs lost at Australian universities during Covid pandemic. (https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/feb/03/more-than-17000-jobs-lost-at-australian-universities-during-covid-pandemic), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- WA universities lose millions as COVID’s bite continues to be felt. (https://www.watoday.com.au/national/ western-australia/wa-universities-lose-millions-as-covid-s-bite-continues-to-be-felt-20230329-p5cwe5. html), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- Swinburne staff warned of job cuts as universities’ COVID-19 woes grow. (https://www.theage.com.au/ national/victoria/swinburne-staff-warned-of-job-cuts-as-universities-covid-19-woes-grow-20200603- p54z6s.html), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- Swinburne University staff condemn leadership over ’excessive’ cuts to courses, jobs. (https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/swinburne-university-staff-condemn-leadership-over-excessive-cuts-to-courses-jobs-20201112-p56dyy.html), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- RMIT, Swinburne, La Trobe post hefty deficits but not all unis in the red. (https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/rmit-swinburne-la-trobe-post-hefty-deficits-but-not-all-unis-in-the-red-20210504-p57ova.html), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- Swinburne welcomes international students back to campus. (https://www.swinburne.edu.au/news/2021/11/swinburne-welcomes-international-students-back-to-campus/), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- Swinburne’s strategic focus delivers financial turnaround – 2021 Annual Report released. (https://www.swinburne.edu.au/news/2022/05/swinburnes-strategic-focus-delivers-financial-turnaround-2021-annual-report-released/), Accessed: 2023-02-07.

- Dinh, T., Thirunavukkarasu, G., Seyedmahmoudian, M., Mekhilef, S. & Stojcevski, A. Predicting Commercial Building Energy Consumption Using a Multivariate Multilayered Long-Short Term Memory Time-Series Model. Applied Sciences. (2023).

- Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation. 9, 1735-1780 (1997).

- Huang, S. Robust learning of Huber loss under weak conditional moment. Neurocomputing. 507 pp. 191-198 (2022).

- Schuster, M. & Paliwal, K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions On. 45 pp. 2673 - 2681 (1997,12) https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1435.

- Liu, Z., Wu, D., Liu, Y., Han, Z., Lun, L., Gao, J., Jin, G. & Cao, G. Accuracy analyses and model comparison of machine learning adopted in building energy consumption prediction. Energy Exploration & Exploitation. 37 (2019,1).

| Dataset | Model | Metric | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPAE | NRMSE | |||

| 0.061 | 0.047 | 0.931 | ||

| LSTM | 0.366 | 0.100 | 0.690 | |

| M-LSTM | 0.103 | 0.094 | 0.784 | |

| Bi-LSTM | 0.365 | 0.088 | 0.760 | |

| LR | 0.396 | 0.143 | 0.365 | |

| SVM | 0.179 | 0.108 | 0.638 | |

| 0.093 | 0.062 | 0.729 | ||

| LSTM | 0.204 | 0.098 | 0.323 | |

| M-LSTM | 0.098 | 0.123 | 0.391 | |

| Bi-LSTM | 0.211 | 0.077 | 0.588 | |

| LR | 0.270 | 0.196 | -0.699 | |

| SVM | 0.131 | 0.101 | 0.286 | |

| 0.158 | 0.033 | 0.895 | ||

| LSTM | 0.802 | 0.085 | 0.298 | |

| M-LSTM | 0.711 | 0.105 | 0.676 | |

| Bi-LSTM | 0.946 | 0.064 | 0.603 | |

| LR | 0.926 | 0.110 | -0.169 | |

| SVM | 0.389 | 0.068 | 0.550 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).