One study raised the concept of Primary Message Systems (PMS), which encompass ten separate kinds of human activity and non-linguistic forms of the communication process [

13]. According to Hall, this communication system involves: (1) Interaction, (2) Association, (3) Subsistence, (4) Bisexuality, (5) Territoriality, (6) Temporality, (7) Learning, (8) Play, (9) Defence, and (10) Exploitation (use of materials) [

13]. The ingredients of PMS are likely to be observed within street life, where humans tend to share the same impressions, emotions, and behaviours whether between people and the street edge or between each other. To a large extent, people have the same reactions and interactions to a given built setting. The origin of such responses to objects is inherent in people’s consciousness and reflects in their behaviour. According to [

13], three rules (activities) from the PMS can be recognised in street life:

Interactions with, and the definition and utilisation of space are significant criteria for determining the degree of street occupation and its components. Without these, the street could otherwise be considered abandoned. According to Alexander [14, p. 600] the concept of the street edge, which influences street life, is an important factor of a living city. Thus, “the life of [a] public square forms naturally around its edge. If the edge fails, then space never becomes lively [moreover] people gravitate naturally toward the edge of public spaces [so] if the edge does not provide them with places where it is natural to linger, space becomes a place to walk through, not a place to stop”. Furthermore, Hillier [

15] highlighted the two central tenets of territoriality theory and the extent to which they relate to the spatial domain; this denotes the organisation of space by human beings as a biologically determined (individual or collective) impulse that either claims or defends a marked territory against others. However, the theory represents a form of correspondence between socially identified groups and spatial domains, which makes it possible for spatial behaviours to be dynamically connected through the preservation of this correspondence. Although territorial theory explains the relationship between human behaviour when occupying space and the space itself, Hillier believed it is limited in its attempt to locate the origins of spatial order in the individual biological subject [

15].

2.1. Street Life and Urban Form

Urban elements in a city are part of a shared milieu which embrace people and activities. Thus, designers are responsible for enabling and accommodating this sharing and for the different patterns of urban entities where elements are broader than specialised design expertise. In other words, when making a decision, the design principle for any part of a city cannot generally be separated from its daily life, the social activities of urban areas, and the other influences and institutional considerations [

7]. Also, Carmona [7, p 201, 203] studied people’s movement in space, stating that it is crucial to enable a dynamic street and that, “movement is fundamental to understanding how places function. Pedestrian flows through public space are both at the heart of the urban experience and important in generating life and activity … Most shops, for example, are not a sufficient magnet and have to be well-located with respect to the existing movement patterns. The land-use activity merely reinforces/multiplies the basic movement” [7, p 201, 203].

For Montgomery [

16], the key to successful places is their ability to make different kinds of transaction possible between diverse activities. Montgomery argued that, without a transaction pattern for a wide variety of activities at many levels, it is not possible to create attractive urban places and a vibrant street life. For example, as not all transactions are economically-based, urban areas and cities must also allow space for social and cultural interactions. Montgomery listed a number of key indicators for vitality, one of which is the presence of an active street life and active street frontages. Furthermore, Kostof [17, p 123] stated that, “streets are public places: so is the harbour waterfront ... But streets and quays are primarily places of transit, capturing public life in momentary pauses from a river of people in motion. The public place, on the other hand, is a destination; a purpose-built stage for ritual and interaction. Broadly, the reference is to places we all are free to use, as against the privately-owned realm of houses and shops” [17, p 123].

Furthermore, Kostof [17, p 124] referred to the meaning of democracy when addressing the public realm of a city, stating that “the life and control of the public [is] indeed the fundamental aim of the public place is to ensconce community and to arbitrate social conflict. The program is a paradox. The square is where we exercise our franchise, our sense of belonging. We are meant to come and go as we please, without the consent of authorities and without any declaration of a justifying purpose” [17, p 124].

In comparison, one study conceptualized space through the significance of cultural and social values [

18]. It argued that “culturally and socially, space is never simply the inert background of our material existence. It is a key aspect of how societies and cultures are constituted in the real world, and, through this constitution, structured for us as ‘objective’ realities. Space is more than a neutral framework for social and cultural forms. It is built into those very forms. Human behaviour does not simply happen in space. It has its own spatial forms. Encountering, congregating, avoiding, interacting, dwelling, teaching, eating, conferring are not just activities that happen in space. In themselves, they constitute spatial patterns… But the relation between space and social existence does not lie at the level of the individual space, or individual activity. It lies in the relations between configurations of people and configurations of space” [18, p 29, 31–33].

Moreover, another study outlined a number of aims for a good urban environment which include: livability or whether the city is a comfortable place to live; identity and control, or whether it enables the sense of individual or collective belonging to an urban environment; access to opportunities, or whether there are chances to interact with space, people, and activities; community and public life or whether there is the ability to effectively participate in social and public life; and an environment for all, or whether the space is accessible for all people in a desirable and acceptable way [

19]. In comparison, a different study stated that, “the social space of streets is the single contiguous public off of which private spaces are carved… the public-private filtering of the building-plot-street system enables settlements to exist – they enable [a] large agglomeration of humans to coexist in a limited area. This is why the streets are not merely voids between blocks of buildings but must be seen as integral to the concept and fabric of a city” [20, p 110].

To add further detail and highlight the interrelationship between social and spatial dimensions, one study stated that street segments “… tended not to appear discretely but were observable sequentially, strung out along the extent of edges formed by overlapping adjacent realms. As one progressed along the extent of such an edge, the degree to which directional or locational attributes predominated tended to change according to local conditions, reflecting the changing type of segment” [2, p 218]. Moreover, “segments are as much social as they are spatial, and as such provide us, at least as an abstract approximation, with the beginnings of a socio-spatial structure capable of integrating social processes and spatial organization. Segments and their accumulation as transitional edges can, therefore, be a focus for design attention. They provide a structural framework amenable to conventional design decision-making processes that can, in optimal circumstances, deliver spatial porosity which then encourages and supports localized expression, coherence and adaptability” [2, p 218].

One of the fundamental aspects of a city’s street life is the need to understand the street as part of a network rather than an individual link. Therefore, it is important to recognize the street as a social network and a connective system for human beings as this helps to promote different patterns of interaction. In this respect, “network analysis is concerned with the structure and patterning of these relationships and seeks to identify both their cusses and consequences” [10, p 507]. Furthermore, the “pattern of interaction and communication [is] the key to understanding social life” [10, p 507 (19; Cooley 1956; Simmel and Wolff 1950, cited in Tichy, N. M., et al. 1979)].

2.2. Social Life and Urban Form

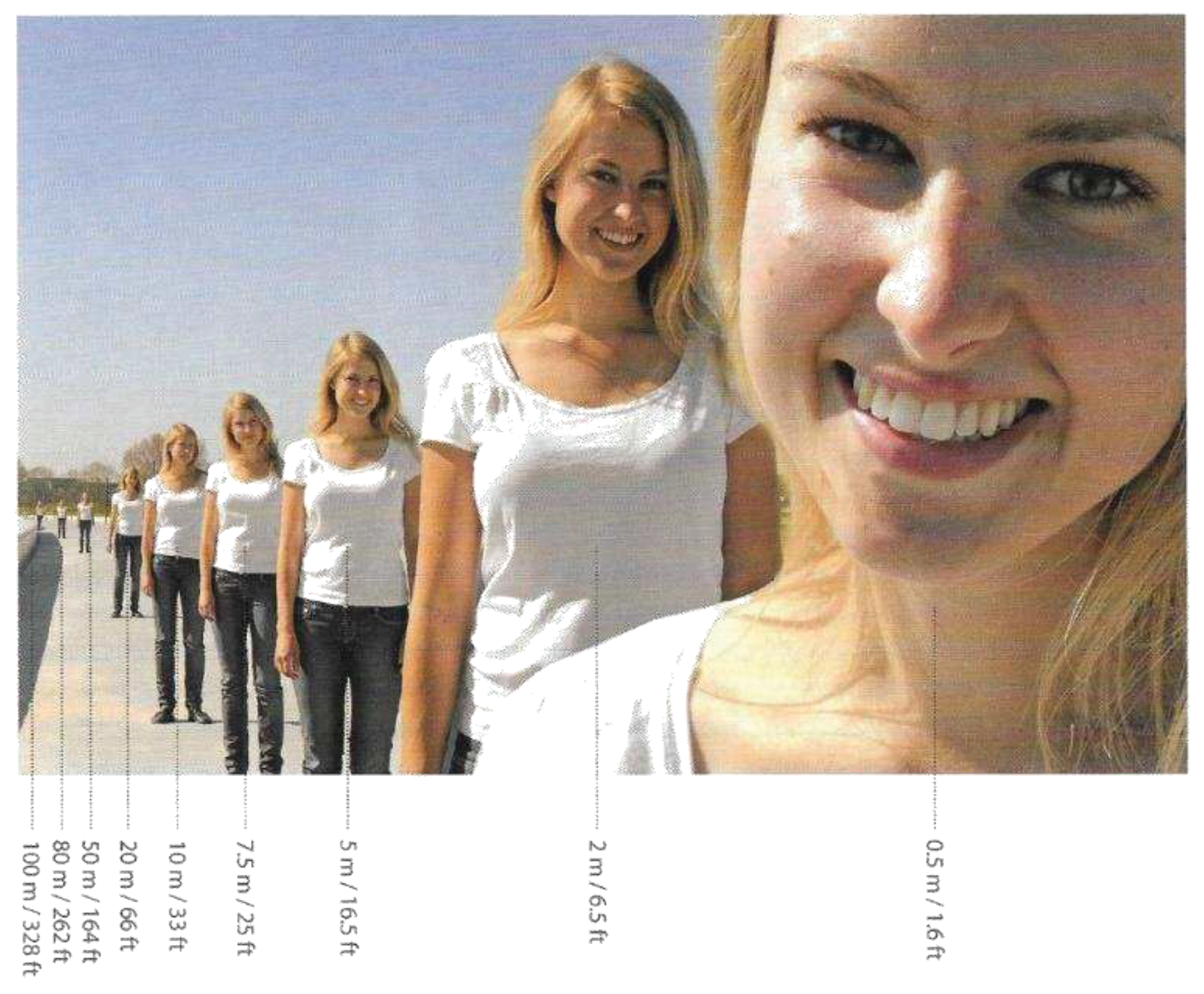

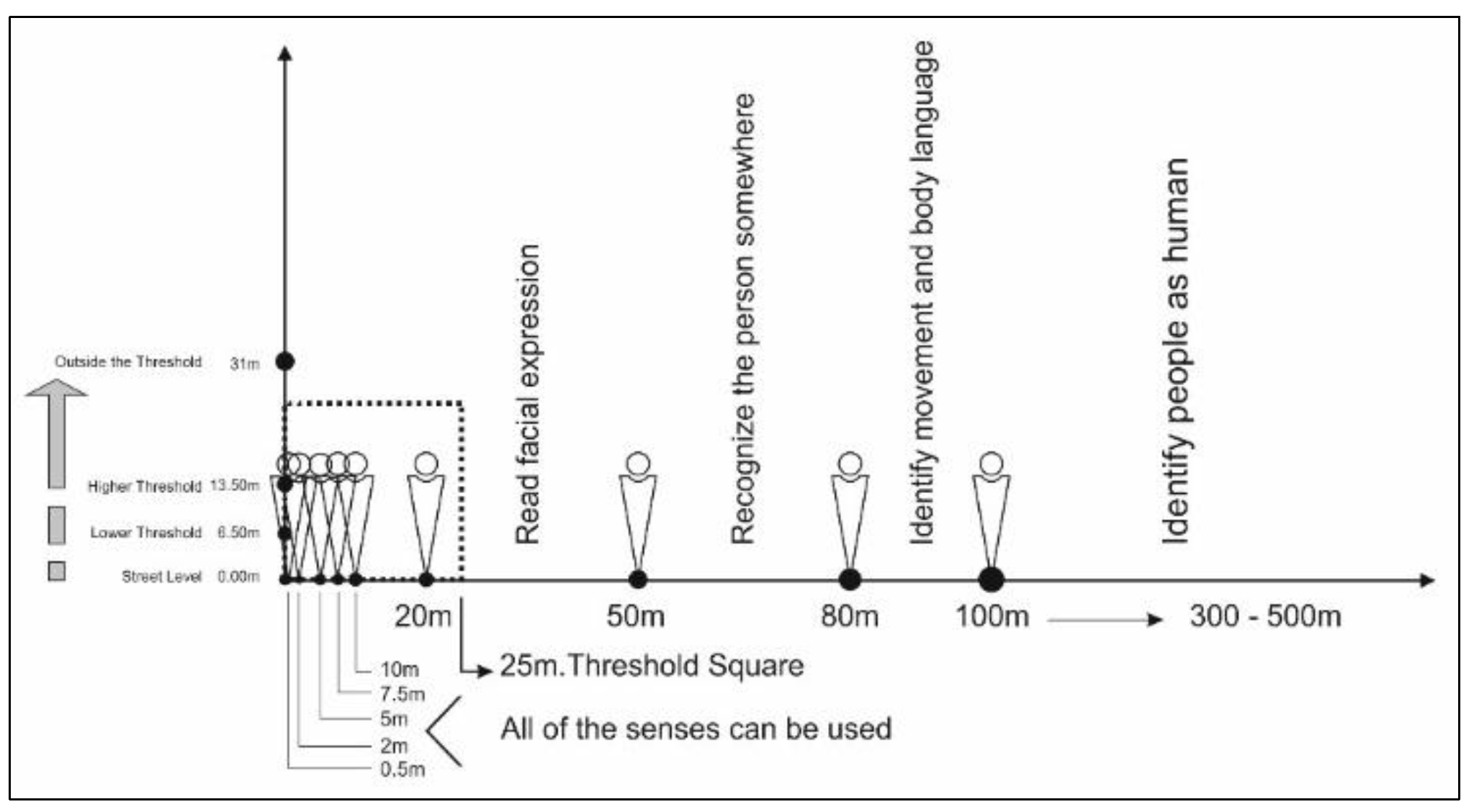

A series of factors and limitations related to the performance of sensory apparatus, are essential to understand and examine the nature of these systems. A number of considerations and limitations concerning the impact of sensory experience needs to be understood in order to understand social life and urban form. For instance, ‘performance’ denotes the relationship between humans and the environment in terms of perception and coexistence. These influences can be divided into two primary levels, firstly, the individual and secondly, the built environment. For the first level, one study noted that the crucial factors for perception are speed, time, and distance, and that humans are responsible for these when there is a wide range of alternatives and opportunities to control movement, time-lapse, and distance [

3]. These opportunities and controls are not spontaneous and independent but depend on the quality of the surroundings, which contribute to the ability of the individual to invest in what the environment offers. The second level relates to the surrounding areas, which include both the natural and built environment [

3].

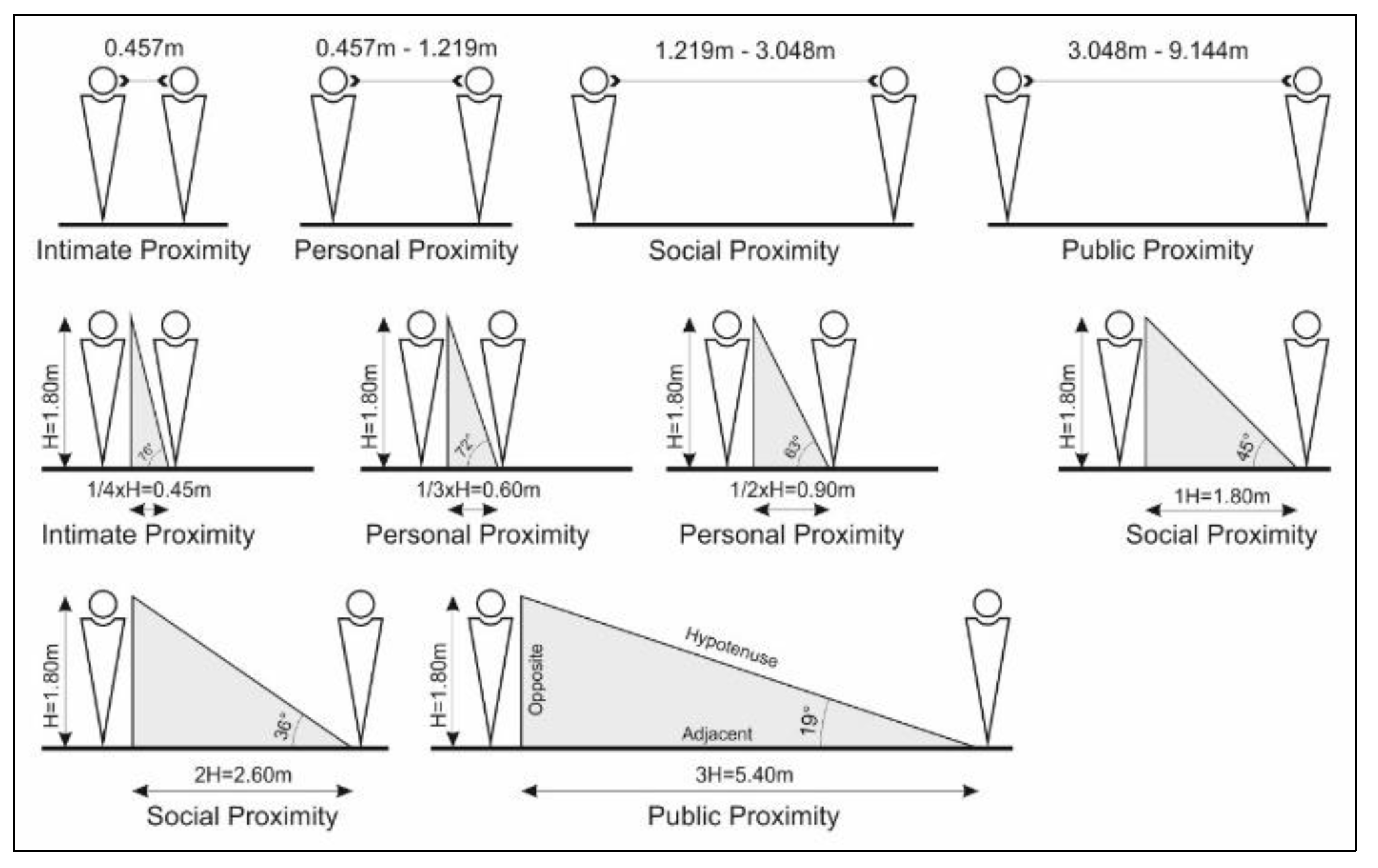

In an argument about the social logic of urban order, it was stated that, “the urban order is not only to do with humans as physical organisms and their individual inclinations; as we shall see, it is also to do with social considerations” [20, p 89-90, 95-98]. Therefore, “human behavior cannot be reduced to the satisfaction of the bodily and mental needs of individual person but must also take account of their social context”. Also, he stated that, “the form and internal structure of buildings will tend to reflect their social organization [and] the city is also inextricable from the human’s status as [a] social - and indeed political - animal; cities are strongly associated with citizenship and civilization” [20, p 89-90, 95-98]. Throughout history, humans have used particular communication systems amongst themselves to make sense of their community, regardless of the pattern and progress of its language. Also, communication enables direct interactions between people without artificial intervention, which makes the activity more social, and vice versa. Gehl offered five categories of communication in accordance with the distance that connects people: (1) intimate distance, which covers about 0.0 – 0.45 metres; (2) personal distance, which covers about 0.45- 1.20 metres; (3) social distance, which covers about 1.20 – 3.70 metres, and (4) public distance, which covers more than 3.70 metres [3, p 47] (

Figure 1).

These five types of proximity are likely to be experienced by those who use a street, as they represent a significant means to enable communication and interaction between people. This was explained as follows “the existence of these communication ground rules is important in order for people to move securely and comfortably among strangers in public space” [3, p 49]. Moreover, the differentiation between distances depends on the purpose of communication and its aim. In one space, there can be an opportunity to experience some contact among individuals at different distances (

Figure 2).

Also, the relationship between people is typified by the distance between those who use the space, and includes intimate, personal, social and public distances [

1], [

13] (

Figure 3). The meaning of proximity was also addressed through a taxonomy of relationships between people based on the nature of the messages communicated [

21]. These include: (1) Functional/Professional; (2) Social/Polite; (3) Friendship/Warmth; (4) Love/Intimacy; and (5) Sexual/Arousal [21, p 272-273]. Thus, a city’s ability to offer different levels of communication among its people by connecting distance, intensity, closeness, and warmth can help to raise its quality.

A lack of perspective is perceived as the loss of an essential human dimension. However, cities and spaces can be characterised by patterns of planning that provide considerable opportunities to make people feel like significant entities within the pattern by influencing each other. Moreover, space has been defined as a factor in cultural contact that influences communication, “spatial changes give a tone to a communication, accent it, and at times even override the spoken word. The flow and shift of distance between people as they interact with each other is part and parcel of the communication process” [13, p 175-176]. This understanding of informal spaces suggests the need for a hypothesis to explore the classification system of proxemics and the dynamism of space. Thus, a four-part classification system was distinguished to read the range of distances which mediate among people, namely intimate, personal, social, and public [

1]. Therefore, to bring the meaning of culture into space, planners were invited to be aware of the relationship between space and culture; “city planners should go even further in creating congenial spaces that will encourage and strengthen the cultural enclave. This will serve two purposes: first, it will assist the city and the enclave in the transformation process that takes place generation by generation as country folk are converted to city dwellers; and second, it will strengthen social controls that combat lawlessness” [1, p 174].

In addition, a further definition was offered of the interrelationships within urban form through the spaces and people who perform social and cultural activities [

22]. Thus, “space can be seen as a key aspect of how our social and cultural worlds are constituted in the physical world and structured for us as objective realities. Space is not the neutral framework for social and cultural forms. It is built into those very forms. It is because this is so that buildings can carry within their spatial forms the kinds of social knowing that Glassie notes” [22, p 11]. This means the physical environment can shape social meanings through signs and symbols which are fundamentally understood by society [

15]. For example, the street edge and transitional edge (as defined by [

2]) play a crucial role in formulating social interactions. Thwaites et al. [

2] state that this is evolutionary in its development and essentially expressive in its nature. Moreover, both the growth and development of the transitional edge as a street edge emerges from expressions of territorial occupation and use. Therefore, it represents an interdependent relationship between the social and spatial dimensions of the urban structure.

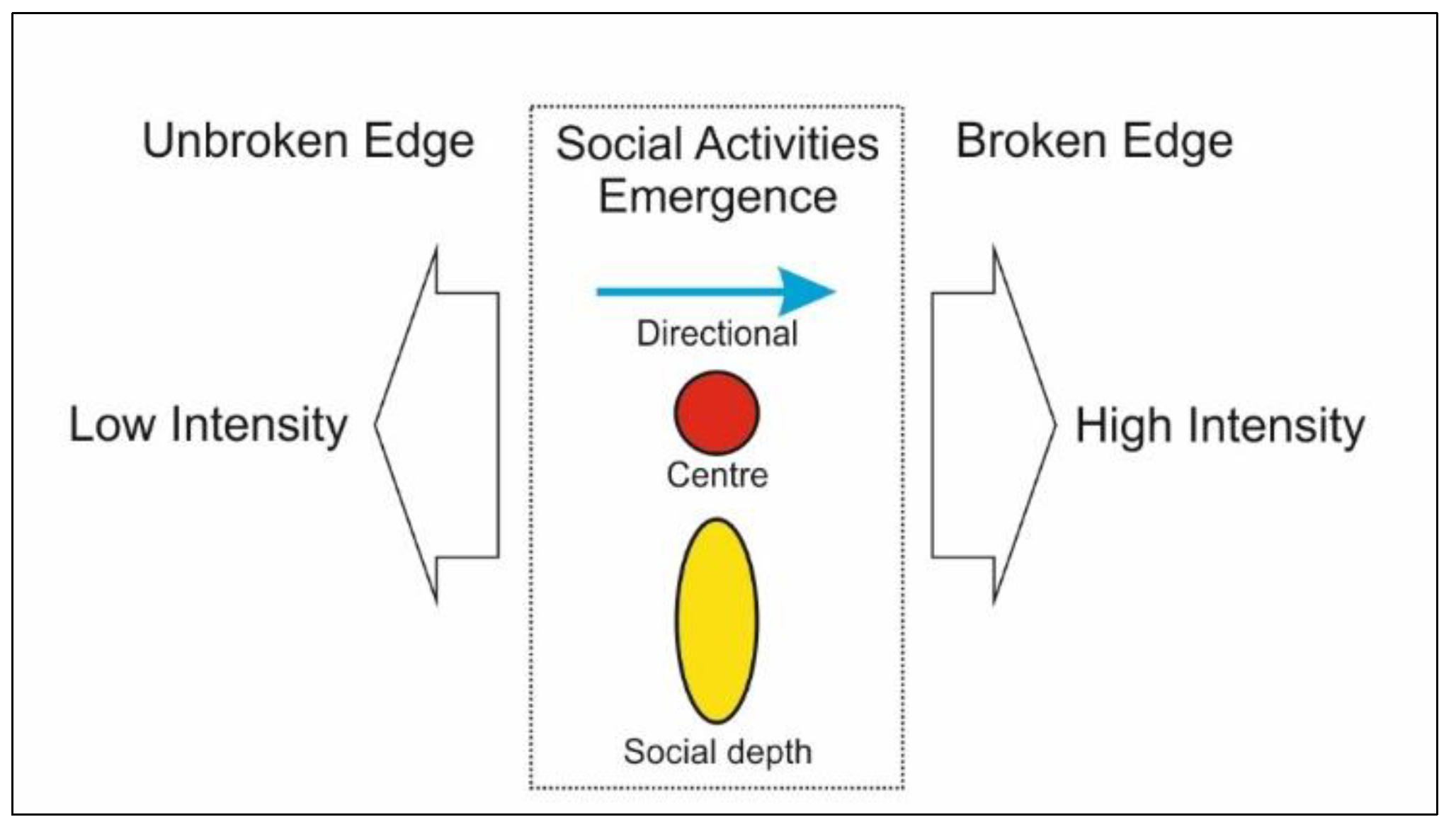

The transitional channel, namely the street edge, characterizes coherent, holistic socio-spatial realms in order to integrate spatial and social aspects of the urban form. In this respect, “the social dimension of transitional edges derives from interactions which generate engagement, action, and change. …[Consequently,] [t]ransitional edges thus become the visible socio-spatial form of built environments: that which gives meaning through use, character and identity through territorial expression, and sustainability through adaptation” [2, p 78]. In addition, a distinction was made between social activity and social interaction, by defining social activity as, “soft, active or engaging edges are commonly associated with social activity, usually generated by their capacity to hold the attention of passers-by. Such edges are also associated with transitional qualities defining an overlap of adjacent realms, their social activity related to accessibility across it and opportunities to be stationary coupled with things that can hold attention” [2, p 81, 83]. In comparison, social interaction was defined as, “the transitional nature of edges … associated with social interactions because of [the] qualities they possess which support stationary activities. It appears, therefore, that transitional edges, as elements of urban form, have a significant role to play in encouraging and sustaining the social dynamic of the urban realm” [2, p 81, 83].

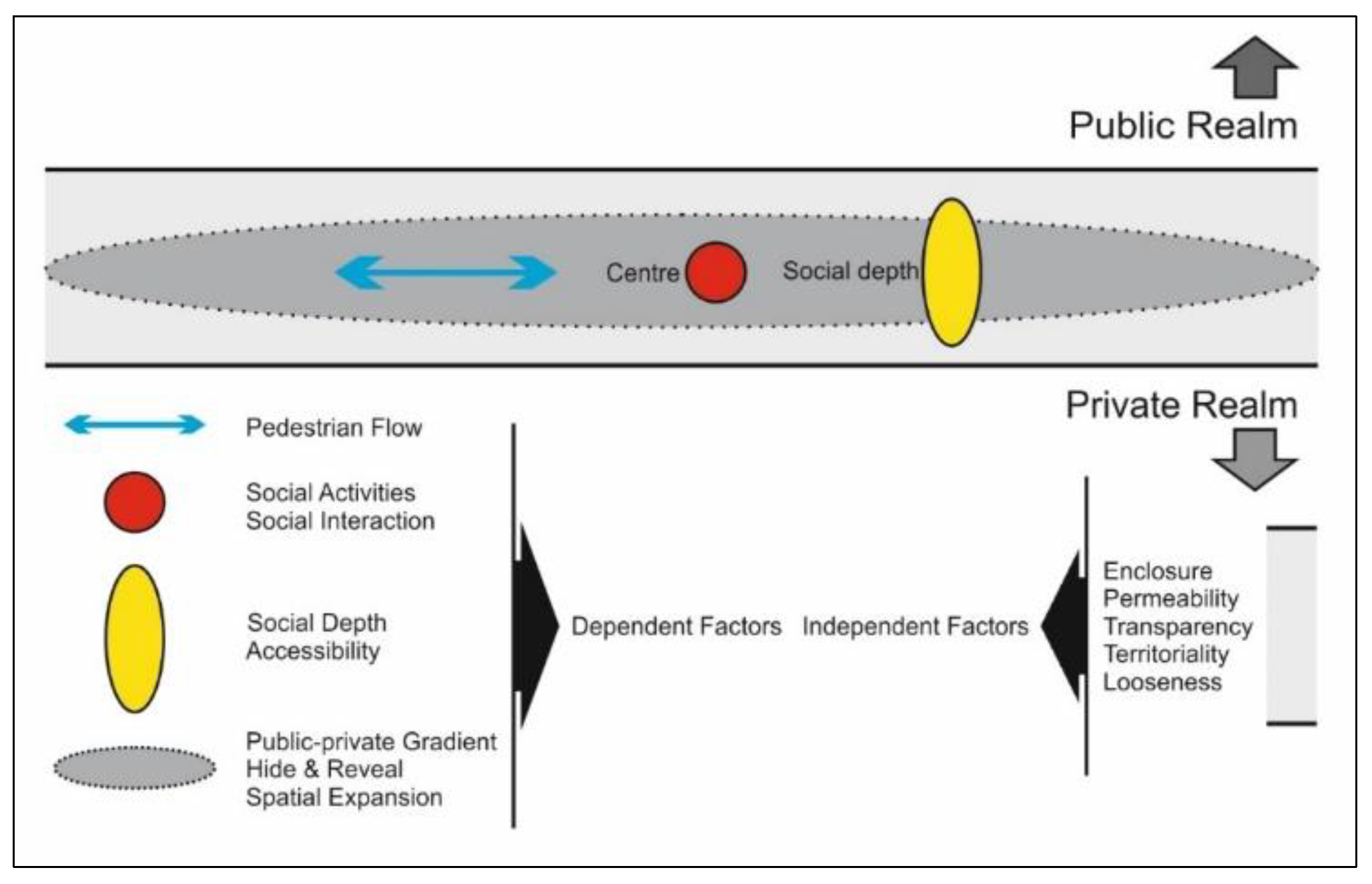

Furthermore, three fundamental factors have been outlined which play a vital role in the interactive value of such a segment: direction, centre, and social depth [

2]. These can be regarded as catalytic points or motivational spots that attract people to create an interactive dialogue. The three factors are governed by ten themes (social activity, social interaction, public-private gradient, hide and reveal, spatial expansion, enclosure, permeability, transparency, territoriality, looseness) and in turn determine the degree to which social activities take place in the surrounding environment (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). For example, some have argued that successful centers should offer three fundamental functions [

23]. Firstly, there should be social imageability in terms of facilities, pronounced physical features, visual variety and complexity, and social meaning. Secondly, there should be opportunities for social interaction which can be achieved by a significant convergence of routes, functions for waiting, seating in social groupings, features to encourage comment, revealingness, and places for arrival/departure. Thirdly, there should be restorative benefits, including separation from distraction, comfort and shelter, provision for rest, and the presence of nature [23, p 60-65].

In this regard, “if you want a structure that encourages social interaction, you must have human paths crossing; but if you want people to interact, there must be something that will encourage them to linger. Differences in interaction frequency are often related to the distances people must travel between activities” [21, p 126].