Submitted:

07 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

The role of health providers

Intersectionality in service care for GBV survivors

Methods

- Study design

- Study instruments

- Study setting, and recruitment procedure

- Study population

- Study population and data collection procedure

Data analysis

- Ethical approval and consent to participate

Results

- A.

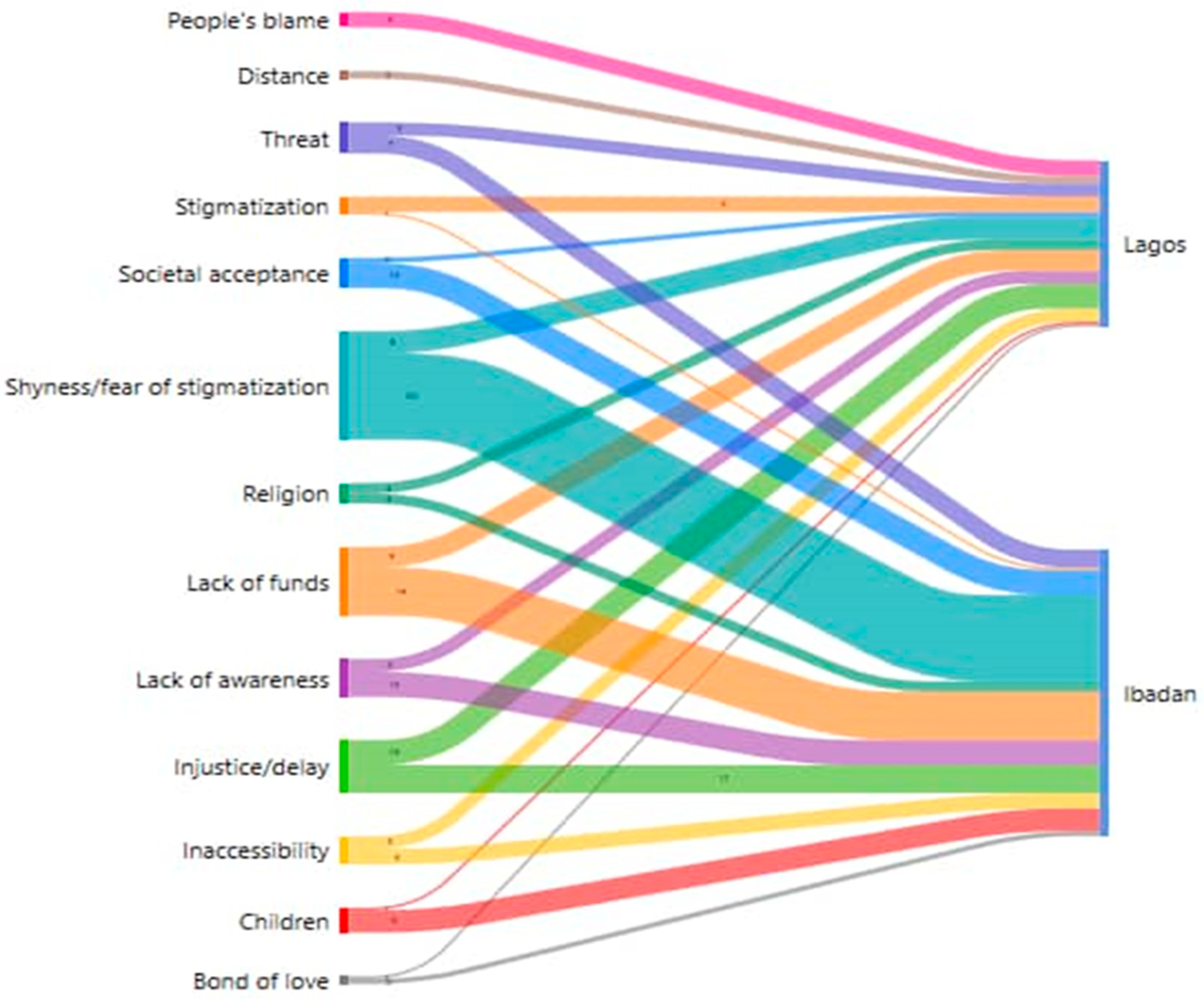

- Violence experiences and barriers in reporting

- 1)

- Factors responsible for not reporting abuse or utilizing health services for support

- Culture of silence among survivors of abuse

…..constant abuse, but It’s very rare cases where people come and report, so even there’s no forensic evidence, and the fact that, the community they live in, when you report abuse or rape, how are other people going to perceive you? I think it is a cultural issue for the community, the lack of voices. Moreover, people do not believe in the justice system. (Medical doctor, Sango Lagos)

[..] Culturally, it is not so much acceptable, they will believe that, “let us just cover it” so that at the end of the day, they will not be abusing the girl. Socially, they may be embarrassed so they will want to keep it [...]. (KII Health worker, Dopemu Lagos)

- Stigma; being judged, blame syndrome, discourage reporting

[…] Most of the concern they face is parent discouraging them in reporting, then fear of stigma, fear of being shouted at too, fear of – “I don’t know what-- people around, when they broadcast this issue now, I don’t know what my friends will see me as […]. (KII Health worker, Powerline Lagos).

People will blame them that before they started the relationship, why do not they seek counsel, so if they will have to report. [..]’ ‘[..] Because they are scared of what people are going to say, they are scared of being stigmatized. And again, due to the threat from the perpetrator […]’ (FGD Dopemu, Lagos)

- Fear of re-victimization from perpetrator and lack of confident in justice

[…] the perpetrators ran away to another environment immediately they commit the crime, they returned to the community with the hope that people would have forgotten the incident. I witnessed a case where a girl was raped of recent the perpetrators were caught and sent to prison, they have been released now. (IDI AYW, Soretire Lagos)

[…] when a woman is going through unpleasant things in her relationship and does not want her home to be separated if she wants to talk about her husband outside, she will say pleasant things even among her family members. A woman whose husband beats in the morning and she visits her family and she was asked how her husband is doing, hope he has stopped beating you? …She will say ‘we had our bath together this morning, he fetched water for me, I was in the kitchen, he bathed and took the child to school” -because she does not want her home to be scattered….so, she will have to bear it […]. (IDI AYW, Oniyanrin Ibadan)

- 2)

- Barriers in accessing support services and help for abuse/victims

- Finances; lack of money by AYW and family:

[…] most of them go to pharmacist and go to the hospital. If they have money, they will visit the hospital and the one that does not use hospital finds alternative (R2…FGD Oniyarin Ibadan)

[…] I think is that there is no way one will go to the hospital and they will not request for money, so if the person is capable and has the money she will go there (R8…FGD Oniyarin Ibadan)

…..the police cannot render any help, there is no police you go to that you will not spend money so there is no help police can render when it is not that we took a matter there, if she need support from police they cannot help her. And if it is government owned hospital, if anything happens to someone or the child even if you go there and they treat you they will end up collect some change (money) they cannot say someone should go free, so that is how it is (R 5 FGD, Ogunpa Ibadan)

- See below in the result section: Figure 1

- Preferred type of services by adolescents and young women in the community

[…] When it comes to rape, they go to private hospitals but not for beating. However, if is forced sex from their sexual partner, some people have nurses they confide in who comes to treat them at home. (Resp. 4, FGD AYW Sango Lagos)

[…] I heard the sound of bottle on my head that day. As I looked back I saw the person I was dating around this area, he lives around here. I suffered that day as blood was gushing out of my body, the cloth I wore turnedto blood all of a sudden… it was Group Medical (hospital) that admitted me […]’. (IDI AYW, Oniyarin Ibadan).

When it comesto pregnancy they go to the hospitals, it could be some government, or private depending on how much they can afford, but for beatings it usually chemist, and rape is definitely private or a nurse. (IDI AYW, Dopemu Lagos)

- 3)

- Support system available for adolescents and young women in the event of violence

[….] we have another support service within the community group. Which is actually a community group, it was founded by the Chamen’s foundation. It comprises of the police, health workers, community people like the Alfa, imams and pastor they form a social community network that fight against abuse. (Health provider, Sango Lagos)

[…] I have also seen a scenario by—a girl came to us and she told us that she was still a virgin though but she wants to do family planning because she knows that she can be raped at any time and she does not want to be pregnant because she understands the environment that she lives in. Even her grandmother consented to it because I was like—so the grandmother gave us the consent that she is actually right. So environment too. (Health provider, Powerline Lagos)

[….] Like I said the other time, okay I have remembered “The child Protection Committee” that has been set up within the community. We do not have it in every community but we have it in few communities like KwaKwa Uku community and few other communities also. Child Protection Association so it is like a link within the community to fight such things (Health Counsellor, Agege Lagos).

- Health care providers’ attitude to AYW and prompt intervention

[…] Adolescents that will go to hospitals go to private hospitals, they cannot go to general hospitals because they will counselthem there and they are not comfortable with it. General hospitals will want to get to the root of the matter, for example, maybe you go there and tell them your husband beat you and from there they will start probing wanting to know what is going on within the person’s family unlike private hospitals. They are just after their money, just pay them and they will treat you without story, they are less concerned about what is happening to you, just give them their money and you are good to go […]. (Resp. 3, FGD AYW Sango Lagos)

[…] They come to us. We have a contact with Lagos State where we can contact them and get in touch. We have some NGO’s that we work together like Hello Lagos. Hello Lagos has their branch at LASUTH, also at Agege too. So when such case is been found, it’s either I report to Hello Lagos LASUTH or I put to my office directly and they take it up, you know, ask the girl to come, fix her up. Then go through the protocol, then to Lagos State Domestic Violence Respond Squad […]. (Health provider, Powerline Lagos)

- Support by health providers for victims that utilizes service

‘[…] Like the one I referred to the other time the girl, seventeen years old was actually with her estranged boyfriend and she was stabbed with bottles on her hand and she had a baby and the baby was subtly taken away from her and all those stuffs. The mother came in and I had to refer the mother to the hmmmm-there is a center in the maternity that deals with violence […]’. (Health Counsellor, Agege Lagos).

‘[….] So whenever she comes for clinic, she does not interact, laugh nor smiles. Then one day, I called her, and asked her what the problem is, it was there she narrated the story that the mother in-law is not treating her well and her parent had warned her never to come back home. UCH organized one program/project on adolescents’ pregnancy. I had to inform them; they went to the place and settle the matter because I noticed she is already becoming depressed […]’. (Matron Ayeye, Ibadan).

‘[…] Unless only if the victim is injured, we take it up just to save the life of the girl, because sometimes if we refer them to ‘Adeoyo’ hospital, they we not go. So, we try and do some tests for them, like HIV test and give them and if there is none, we move further to pregnancy test, that is our limit, we don’t have any power other than that’. (Matron Oniyanrin Ibadan)

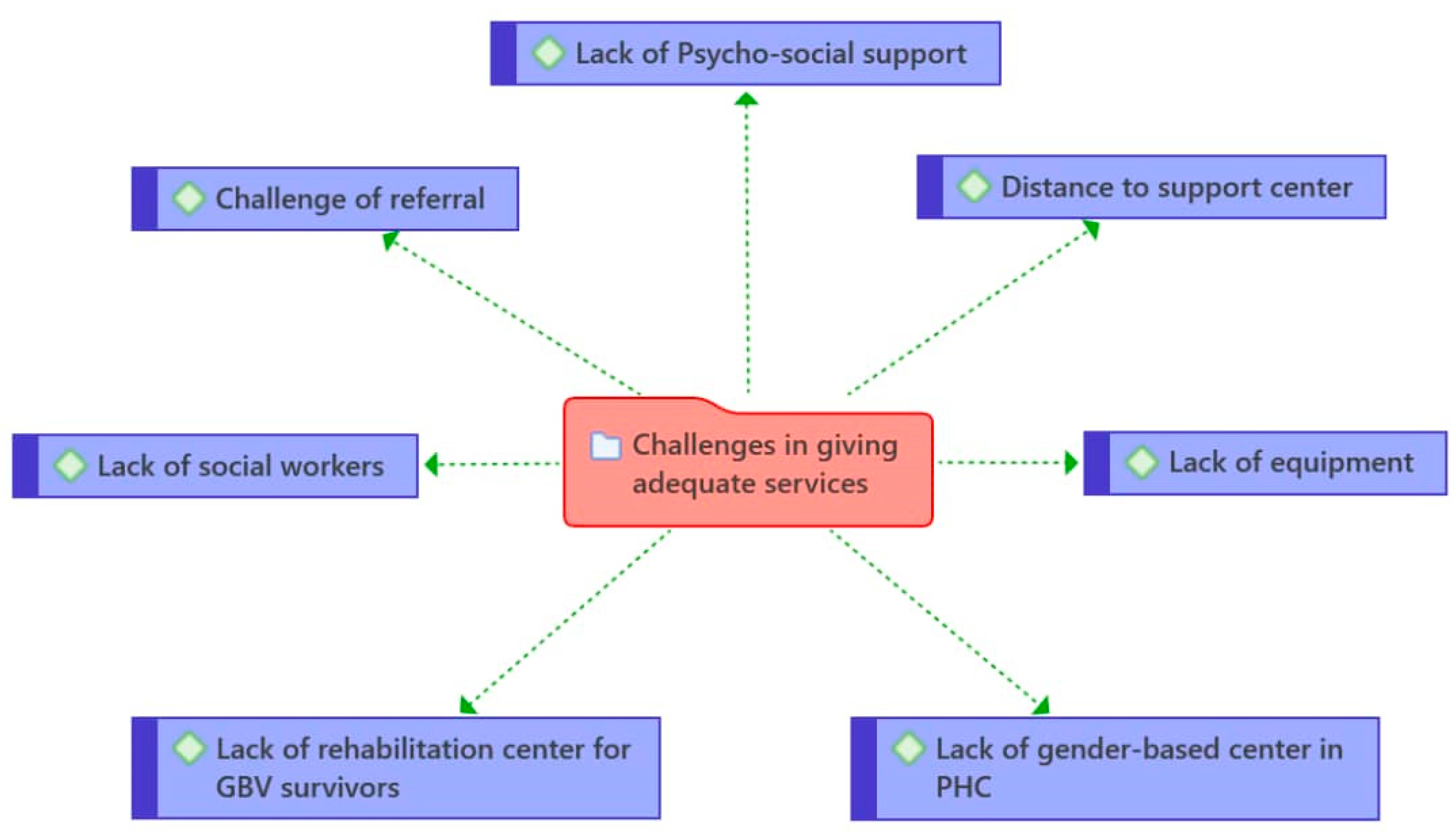

- Health care providers’ challenges in supporting violence victims/survivor

[…]There are no social workers in this community, if there were, they would be confronted with such problem as the woman who said she wanted to commit suicide […]. (Matron Ayeye Ibadan)

‘[…] In every local government, I believe there is a need to have a rehabilitation center for abuse or cases of abuse. Like now, I have case of abuse and I am going to Ikeja general hospital […]’. ‘[…] the survivors of GBV you can counsel them like I said but the treatment would not be entirely 100% fixed. The treatment would not be that comprehensive within the primary health center within the locality because we do not have a particular unit of it, so, if such office that is actually responsible for just gender-based violence for young people, it would actually go a long way […]’. (Health providers, Agege Lagos).

[….] is that most of these offenders we do not take them to rehabilitation homes before they are being jailed to prison or releasing them back into the community. They need to undergo rehabilitation; we need to have rehabilitation center probably within the local government at least two or three centers within the local government (Health Counsellor, Agege Lagos).

- Health providers’ professionalism in treating victims of GBV

[….] Like the one I referred to the other time the girl, seventeen years old was actually with her estranged boyfriend and she was stabbed with bottles on her hand and she had a baby and the baby was subtly taken away from her and all those stuffs. I had to refer the mother to the hmmmm….there is a center in the maternity that deals with violence also….(Health Counsellor, Agege Lagos).

[….] The major reasons why they need to go through this support service is to get better services. Better services in terms of psycho-social support services, better services on health, better services in managing the victims and the perpetrator also. Better services to manage the girl child to be able to fit in back into the community […] (Health provider, Agege Lagos).

[…] Like I told you that, we don't have much to meet, we don't have solution, we just counsel the person to voice out to look for solution, like me now. I only advised them to please voice out to look for solution […]. (Matron Ayeye Ibadan)

Discussion

- Strengths and limitations

- Implications for policy

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and materials

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- United Nations, UN special representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children. Accessed October 2022, https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/content/girls. 2021.

- United Nations, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Accessed October, 2022 https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. 2015.

- United Nations, Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016-20230). Accessed October, 2022 https://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org/pdf/EWEC_globalstrategyreport_200915_FINAL_WEB.pdf. 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents ( AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Accessed October, 2022 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512343. 2017.

- World Health Organisation (WHO), Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent’s Health 2016-2030. Accessed October, 2022 https://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org/. 2015.

- World Bank, Violence against women and girls – what the data tell us. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/overview-of-gender-based-violence/. 2022.

- UNFPA, ICPD Beyound 2014, High-Level Global Commitments: Implementing the Population and Development Agenda. Accessed October, 2022 https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/ICPD_UNGASS_REPORT_for_website.pdf. 2016.

- United Nations, Convention on the elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 20 December 1979. United Nations Human Rights office of the high commissioner. Accessed October, 2022 https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women. 1979. 18 December.

- ICF, N.P.C.N.a. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF. 2019.

- ICF, N.P.C.N.a. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF. 2013.

- Egbe IB, A.O., Itita EV, Patrick AE, Bassey OU. Sexual Behaviour and Domestic Violence among Teenage Girls in Yakurr Local Government Area, Cross River State, Nigeria. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 9.

- Okey-Orji S, A.E. Prevalence and Perpetrators of Domestic Violence against Adolescents in Rivers State. Arch. Bus. Res. 2020, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyemi K, O.T., Ogunnowo B, Onajole A., Sexual Violence Among Out-of-School Female Adolescents in Lagos, Nigeria. SAGE Open 2016, 6.

- Adegbite, O. and A. Ajuwon, Intimate partner violence among women of child bearing age in Alimosho LGA of Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research 2015, 18, 135–146.

- Herrero-Arias, R., et al., Keeping silent or running away. The voices of Vietnamese women survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Glob Health Action, 2021, 14, 1863128. [CrossRef]

- Rodella Sapia, M.D., et al., Understanding access to professional healthcare among asylum seekers facing gender-based violence: a qualitative study from a stakeholder perspective. BMC Int Health Hum Rights, 2020, 20, 25. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E., et al., Implementation of a Family Planning Clinic-Based Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion Intervention: Provider and Patient Perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 2017, 49, 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, E., et al., Getting dirty: Working with faith leaders to prevent and respond to gender-based violence. The Review of Faith & International Affairs. 2016, 16, 22–35.

- UN Women, Handbook for national action plans on violence against women. Accessed October 2022 https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2012/7/HandbookNationalActionPlansOnVAW-en%20pdf.pdf. 2012.

- World Health Organization, Strengthening health systems to respond to women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: A manual for health managers. Access August 2022 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259489. 2017.

- García-Moreno, C., et al., Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet, 2015, 385, 1685-95. [CrossRef]

- Briones-Vozmediano, E., et al., Professionals' perceptions of support resources for battered immigrant women: chronicle of an anticipated failure. J Interpers Violence, 2014, 29, 1006-27. [CrossRef]

- Ogbe, E., et al., The potential role of network-oriented interventions for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence among asylum seekers in Belgium. BMC public health. 2021, 21, 1–15.

- Fawole, O.I., A.J. Ajuwon, and K.O. Osungbade, Evaluation of interventions to prevent gender-based violence among young female apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Education, 2005.

- Wada, O.Z., et al., Gender-Based violence during COVID-19 lockdown: case study of a community in Lagos, Nigeria. African Health Sciences 2022, 22, 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Azuh, D.E., et al., KNOWLEDGE AND PREDICAMENTS OF GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE IN SOUTHWEST NIGERIA. Proceedings of ADVED, 2021. 2021(7th).

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review. 1991, 46, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, N.J. and I. Dupont, Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: Challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence against women 2005, 11, 38–64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzanka, P.R. From buzzword to critical psychology: An invitation to take intersectionality seriously. Women & Therapy 2020, 43, 244–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami, A. and O. Hankivsky, Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. Lancet 2018, 391, 2589–2591. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapilashrami, A. What is intersectionality and what promise does it hold for advancing a rights-based sexual and reproductive health agenda? BMJ Sex Reprod Health, 2019.

- Worldometer, Elaboration of data by United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects:The 2019 Revision. Accessed October, 2022 https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nigeria-population/. 2019.

- UN-HABITAT, Population living in slums (% of urban population)-Nigeria. United Nations Human settlements programme. Accessed October 2022 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?locations=NG. 2016.

- Gale, N.K., et al., Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013, 13, 117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A., P. Sainsbury, and J. Craig, Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapilashrami, A. and S. Marsden. Examining intersectional inequalities in access to health (enabling) resources in disadvantaged communities in Scotland: advancing the participatory paradigm. Int J Equity Health 2018, 17, 83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetters, M.D. The mixed methods research workbook: Activities for designing, implementing, and publishing projects. 2020: SAGE Publication.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).