1. Introduction

In the 21st century, many museums have come to realize that the human skeletons they display sometimes have problematic origins (Alberti et al., 2009; Knoeff and Zwijnenberg, 2015; Swain, 2016; Overholtzer and Argueta, 2018; Jacobs, 2020; Stantis et al., 2023). The tradition of showcasing human remains goes back to the Early Modern Period (a.k.a. the Renaissance Period), when the first anatomical collections were assembled (Knoeff and Zwijnenberg, 2015). Autopsies were then performed in public, and human skeletons were put on display for the general population, with particular benefit for students of medicine, biology and art. A tradition evolved that allowed dead human bodies to be presented and viewed in a museum context “apparently isolated and insulated from society’s normal relationships with the dead: grief, morbidity, respect, invisibility” (Swain, 2016).

Today, that tradition is being challenged. Plastic skeletons and digital 3D models have replaced real skeletons as pedagogic tools. Furthermore, many anthropological skeletal collections originate from anatomical dissection of the executed and the very poor, or from scavenged graves of indigenous people during colonial times (Alberti et al., 2009; Knoeff and Zwijnenberg, 2015; Stantis et al., 2023). In particular the older collections have been assembled at a time when personal integrity was not a human right, and when people of the lower strata of society had very few rights at all. Current laws and ethical sentiments are very different, with a strong focus on individual consent. Clearly, most anthropological collections involve skeletons of individuals who did not consent to ending up as museum inventories. Such collections are therefore being re-evaluated in many countries (Alberti et al., 2009; Overholtzer and Argueta, 2018; Stantis et al., 2023), and repatriating or reburying museum skeletons have become viable options.

But what are the correct procedures for handling human remains when the deceased people’s last wills and wishes are unknown, as is the case for most museum collections? If no living descendants can be identified, a deceased person’s wishes and beliefs may be estimated from the traditions and religious practices of that person’s cultural group. It therefore becomes imperative to clarify the cultural affiliations of the human remains kept in museums. This is especially true in cases of possible repatriation – to whom might the remains be returned? But also human remains of unknown origin must somehow be handled, even though the proper course of action can be difficult to establish.

Here, we present and discuss one such difficult case, where a human skeleton of unclear origin in the 1930’s was brought to a museum in Sweden under likely unethical circumstances.

2. Materials and Methods: The Bollnäs Skull

In 1934 the Swedish-born U.S. immigrant Gerhard Linnér, at that time a Los Angeles resident, sent a human skeleton as a gift to the Bollnäs county museum in Sweden. He described it as the skeleton of a “wild Indian” from San Nicolas Island, who had been killed by an arrowhead still sitting in the skullcap. In his gift letter (Appendix 1), Linnér expressed his hopes that adding the skeleton to the museum’s collection would “make visiting the museum even more interesting”. When the Bollnäs county museum closed in the 1970’s, the skull, the arrowhead, and two associated sub-cranial bones (the sacrum and one lumbar vertebra; the other bones had been lost) were transferred to a local high school, i.e., Torsbergsgymnasiet, and used in biology classes. In 2007 the material was transferred to the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, and included in the museum’s collections as object number 2012.04.0001. The museum named the skull after its arrival place in Sweden, and presented it as “the Bollnäs skull” (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left: The Bollnäs skull, with the lithic point protruding from the skullcap. Museum inventory No. 2012.04.0001. Right: Close-up of the lithic point. The scale bars are 1 cm. Photographs by the Swedish Museum of Ethnography (

www.etnografiskamuseet.se), reprinted under a CC-BY license.

Figure 1.

Left: The Bollnäs skull, with the lithic point protruding from the skullcap. Museum inventory No. 2012.04.0001. Right: Close-up of the lithic point. The scale bars are 1 cm. Photographs by the Swedish Museum of Ethnography (

www.etnografiskamuseet.se), reprinted under a CC-BY license.

Examinations at the museum showed that the projectile point (

Figure 1) sits in a hole not created by violent impact, but rather created by manual carving with a sharp tool. Thus, the point’s location is not an original feature, nor is it the cause-of-death of the individual. Instead, it is an intentional post-mortem arrangement, with the likely purpose of making the skull appear more spectacular. As this clearly contradicts the statements that Linnér made about the point, his general truthfulness is in question. The museum staff concluded that they could not fully trust anything in his gift letter, including the claim that the skeleton originated from one of California’s Channel Islands. The museum therefore presented the skull as being of unknown origin.

One of the reasons why the Museum of Ethnography put the Bollnäs skull on display was to illustrate the post-colonial dilemmas currently facing European museums, such as how to handle human remains in museum exhibitions (Alberti et al., 2009; Swain, 2016), and what to do with human remains of unclear origins (Knoeff and Zwijnenberg, 2015). The visitors were encouraged to provide suggestions. The skull’s gift letter, and the projectile point arrangement, both indicate that the skull was brought to Europe under circumstances that today would be considered unethical (UNESCO, 1970). Realizing this, alternatives such as repatriation and reburial were considered but were deemed infeasible, at least as long as the cultural affiliation of the skeleton is unknown. With this in mind, it becomes important to carefully examine the Bollnäs skull and its associated material, to find out if anything can be concluded regarding its origin.

3. Results: Examination of the Bollnäs Skull

The style of the lithic point sitting in the skull (

Figure 1) is previously known from California’s Early (8000-5500 B.C.) and Middle (5500-3000 B.C.) archaic periods (Justice, 2002). This suggests that the people who inserted the point into the Bollnäs skull had access to ancient Californian archaeological material. The point appears to be made from chert, which possibly could be sourced to a particular quarry via chemical analysis (Eker et al., 2012; Geilert et al., 2014). And a detailed morphological analysis might be able to clarify the knapping technique used to produce the point (Sholts et al., 2012). But as the point apparently was combined with the skull only in the 20

th c., additional information about the point is unlikely to yield any conclusive information about the origins of the skeleton, even though the two hypothetically could be from the same archaeological context.

For the skull, two features that immediately stand out are the white-washed appearance and the severe dental wear (

Figure 1). The white-washed condition is typical for skeletal material buried in wet sand dunes, which are common along the California coastline and on the Channel Islands. Extensive tooth wear is relatively common in ancient populations, and usually relates to diet. For example, grains processed with grinding stones often contain small abrasive stone particles. But dental wear can also result from using teeth as tools, which was common in ancient California, for example in connection with basket-weaving (Blake, 2011). Thus, the texture and the tooth wear of the Bollnäs skull are both compatible with an ancient California origin, although skulls with these two features can also be found at many other coastal locations.

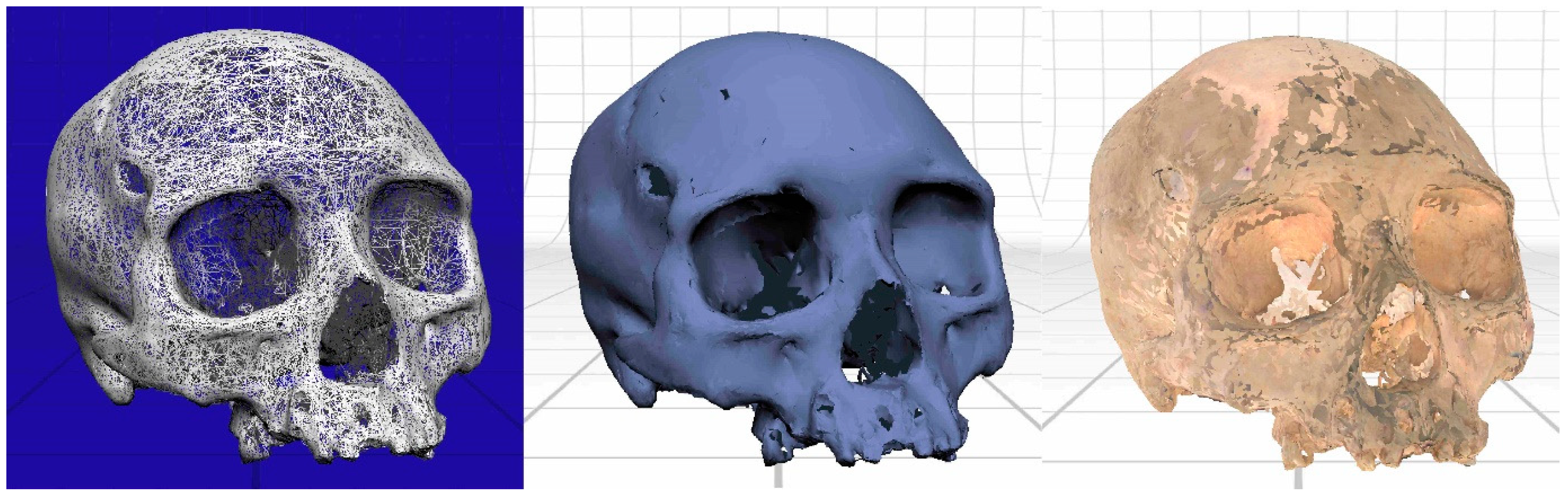

As mentioned above, digital 3D models are increasingly replacing real skeletons in museums and other learning environments. In particular, 3D models can be very useful in situations where displaying the actual human remains, or even accurate photographs of them, might be ethically sensitive. Because 3D models contain different layers of digital data, they can easily be adjusted to show different amounts of information, such as more or less individualizing features. An example is shown in

Figure 2, where a 3D model of the Bollnäs skull is shown in three versions with different levels of detail. This surface 3D model of the skull was recorded with a NextEngine laser scanner, using a previously published scanning protocol for human skulls (Sholts et al., 2010b). In short, 16 scans were recorded: eight scans around the skull positioned “face up”, five scans to capture the orbits, two to capture the respectively right and left zygomatic, and one scan for the posterior aspect of the alveolar bone. The different scans were then aligned and merged into a complete 3D model using the ScanStudio PRO 1.6.3 software (NextEngine Inc.). Such cranial 3D models contain accurate shape information that can help establish an individual’s biological affinity, as well as sex, by matching against skeletons of known origins (Sholts, 2010; Shearer et al., 2012; Sholts and Wärmländer, 2012; Bulut et al., 2016; Petaros et al., 2017; Petaros et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

The Bollnäs skull, shown as a surface-scanned 3D model with different levels of detail. Left: a mesh model, where short lines connect the scanned data points. Middle: a solid 3D model, produced by fusing the mesh model into a continuous surface. Right: A textured 3D model before smoothing, where 2D color photographs of the skull have been mapped onto the solid 3D model. Images by SW.

Figure 2.

The Bollnäs skull, shown as a surface-scanned 3D model with different levels of detail. Left: a mesh model, where short lines connect the scanned data points. Middle: a solid 3D model, produced by fusing the mesh model into a continuous surface. Right: A textured 3D model before smoothing, where 2D color photographs of the skull have been mapped onto the solid 3D model. Images by SW.

But such possible matching typically requires a clear hypothesis, together with reference skeletons corresponding to the hypothesis. As Linnér sent the skeleton from California and claimed that it was of a Native Californian, and as it appears that at least the lithic point in the skull might be from California, it appears relevant to discuss if the skeleton actually could be Californian. In particular, are there facts or features to support or contradict Linnér’s claim that it is from San Nicolas Island? To facilitate that discussion, we first briefly present this island and its history.

4. San Nicolas Island

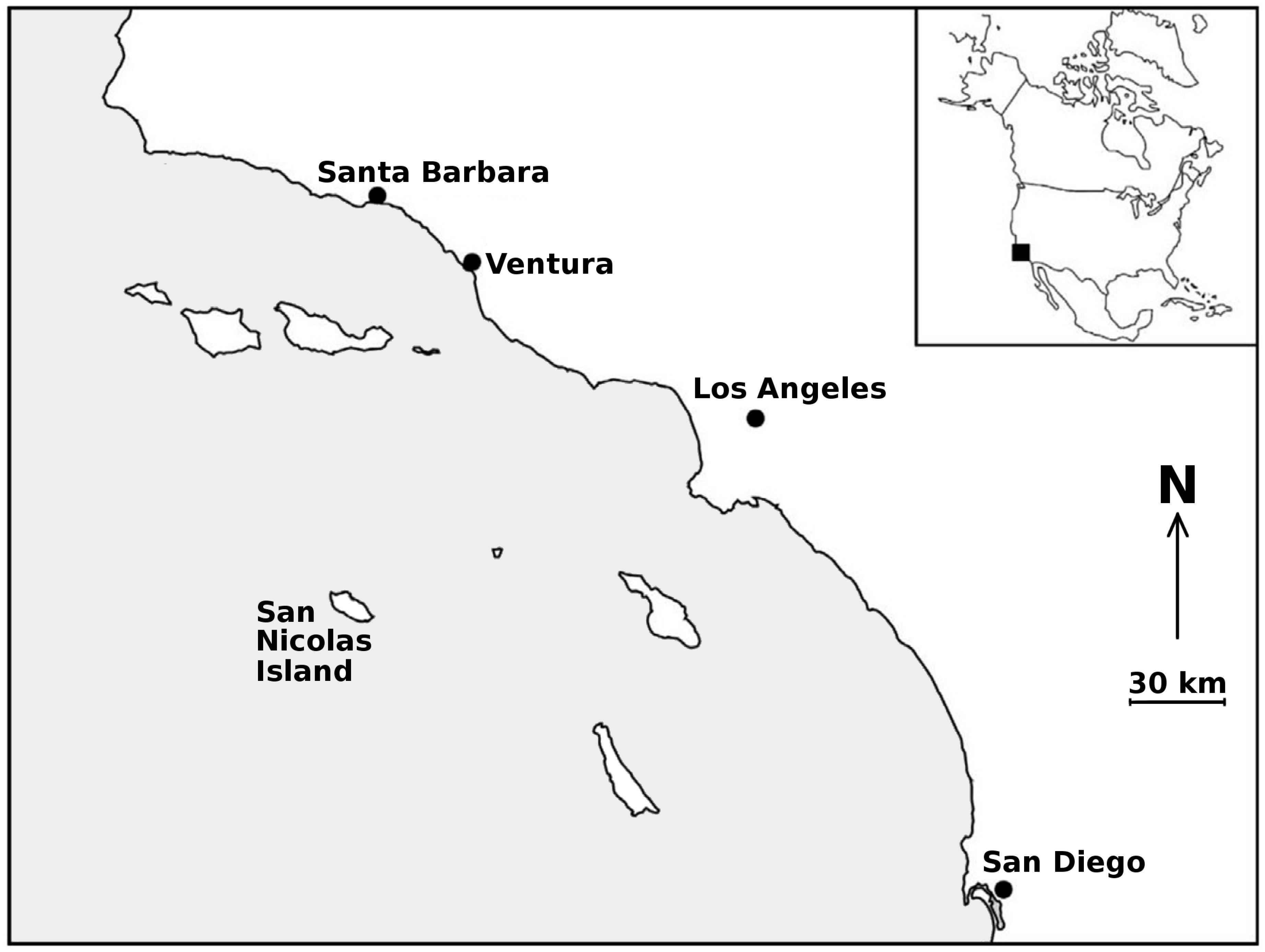

Even though it is the most remote of the California Channel Islands, San Nicolas Island (

Figure 3) has been inhabited for up to 10,000 years (Davis et al., 2010). It is still debated if the island’s inhabitants, known in Spanish and English as the Nicoleños, were a separate Native group with their own language, or if they belonged to the Gabrielino/Tongva group, which inhabited the other Southern Channel Islands (Golla, 2011; Morris et al., 2016). The Chumash group, which inhabited the Northern Channel Islands, is probably more distantly related (

ibid). From the European perspective, San Nicolas Island was discovered and named by the Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno in AD 1602 (Rolle, 1987; Bright, 1998). Under Spanish rule, and also later under Mexican rule, the Native population declined (Morris et al., 2016). In 1835, the remaining Nicoleños were evacuated to Catholic missions in mainland California, where they eventually perished (Morris et al., 2016). Their language died with the people and is now lost. The last San Nicolas inhabitant was a woman known as Juana Maria, who was left behind during the 1835 evacuation. She was found on the island in 1853 and then transferred to mainland Santa Barbara, only to die from dysentery seven weeks later (Morris et al., 2016). Today, San Nicolas remains uninhabited. It is owned and operated by the U.S. military, and archaeological research is conducted to clarify the history of the Nicoleño culture (Vellanoweth and Erlandson, 1999; Harrison and Katzenberg, 2003; Kerr, 2004; Davis et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

Map of the Southern California Bight, showing the location of San Nicolas Island. Drawing by SW, based on

Figure 3 in Smith et al., 2015 (Smith et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Map of the Southern California Bight, showing the location of San Nicolas Island. Drawing by SW, based on

Figure 3 in Smith et al., 2015 (Smith et al., 2015).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Even though Linnér’s gift letter (Appendix 1) contains numerous statements that are untrue, there is one piece of information in it that undeniably is correct, namely that the last inhabitant of San Nicolas Island (i.e., Juana Maria) left the island in 1853. This shows that Linnér was familiar with the island’s history. It also shows that not everything in the letter is made up or wrong. The overall impression when reading it, is that Linnér exaggerated certain details to create an “exciting” story about the skeleton. Thus, the Native Californians are described as “wild Indians”, and Juana Maria is described as being “captured”, when she actually was rescued and left the island voluntarily (Morris et al., 2016). The arrangement with the lithic point sitting in the skull is in line with such dramatic exaggerations, as is the purported rationale for sending the skeleton to the Swedish museum, i.e., to “make visiting the museum even more interesting”. From this point of view, it makes sense that Linnér gives the correct year for the final evacuation of San Nicolas – misrepresenting that detail would not make the skeleton’s story more exciting. The same is arguably true regarding the skeleton’s geographic origin – in the eyes of his Swedish friends, San Nicolas Island would not be a more exciting origin than any other island or mainland location. Thus, why make up or modify that part of the story?

In fact, as the most remote of the California Channel Islands, and being uninhabited since 1853, San Nicolas would have been the ideal location for unofficial archaeological enterprises, where Native American graves could be excavated for less scientific purposes with no one around to ask questions. We therefore argue that Linnér’s statement that the skeleton was taken from San Nicolas Island should not be outright dismissed, but rather be the main hypothesis regarding its origin. This hypothesis can be investigated with techniques such as 14C dating, 3D-based craniometrics, stable isotopes, trace elements, and genetic composition, to narrow down the age, geographic origin, and biological affinity of the skeleton, as has been done for other ancient human remains (Owsley and Jantz, 2014). Unfortunately, the bioarchaeological reference data for the Nicoleño population (Harrison and Katzenberg, 2003; Kerr, 2004; Morris et al., 2016) and the ancient Channel Islanders in general (Sholts, 2010; Sholts et al., 2010a; Sholts and Wärmländer, 2012) is limited. A bioarchaeological analysis of the Bollnäs skull should therefore ideally be carried out in collaboration with the living descendants of the various Channel Islands groups, who could provide access to both modern and ancient samples of comparative biological material.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, and especially former museum director Anders Björklund, for helpful discussions, help with accessing the Bollnäs skull, and permission to use the museum’s photographs.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interrest.

Appendix 1

Linnér´s gift letter (translation by S.W.), sent to the director of the Bollnäs Museum in 1934.

Los Angeles

Jan 16 – 1934

Mr O. Björkman

Bollnäs Museum.

Dear Sir.

First, thank you for Your letter of November 19, 1933. Good to hear that everything arrived home unharmed. Now, don’t be scared. I have sent a skeleton of an Indian. It was found on an island (San Nicolas) in the Pacific Ocean. This island was inhabited by wild Indians right up to the year 1853, when the last ones were captured. According to the director of the Los Angeles museum, this skeleton is one of the best examples of an American Indian. The strange thing about it is that the arrowhead with which the Indian was killed still remains in the skullcap.

The museum here in Los Angeles does not have such a good specimen as this. Now, I don’t know if all bones are included. If You want to assemble the skeleton and some bones are missing, write and let me know and I will try to get them. Otherwise, You can just lay them out on a table. You know best yourselves. I’m sending 4 spearheads and 6 arrowheads in a separate package.

My wish is now that this will arrive home unharmed, and that it will make visiting the museum even more interesting. In the future I will send the Museum some interesting things. Please write and let me know as soon as possible if the package arrived. Now I have to stop for this time, with best regards to all of You back home.

Regards

Gerhard Linnér

1350 so Union ave

Los Angeles

Calif.

References

- Alberti S., Bienkowski P., Chapman M.J. and Drew R. (2009) Should we display the dead? Museum and Society 7(3):133-149.

- Blake J. (2011) Nonalimentary tooth use in ancient California (Master’s Thesis). San Francisco, CA: San Francisco State University.

- Bright W. (1998) 1500 California Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Bulut O., Petaros A., Hizliol I., et al. (2016) Sexual dimorphism in frontal bone roundness quantified by a novel 3D-based and landmark-free method. Forensic Sci Int 261:162 e161-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.01.028. [CrossRef]

- Davis T., Erlandson J., Fenenga G. and Hamm K. (2010) Chipped Stone Crescents and the Antiquity of Maritime Settlement on San Nicolas Island, Alta California. California Archaeology 2(2):185-202. https://doi.org/10.1179/cal.2010.2.2.185. [CrossRef]

- Eker C.S., Sipahi F. and Kaygusuz A. (2012) Trace and rare earth elements as indicators of provenance and depositional environments of Lias cherts in Gumushane, NE Turkey. Geochemistry 72:167-177. [CrossRef]

- Geilert S., Vroon P.Z. and van Bergen M.J. (2014) Silicon isotopes and trace elements in chert record early Archean basin evolution. Chem. Geol. 386:133-142. [CrossRef]

- Golla V. (2011) California Indian Languages. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

- Harrison R.G. & Katzenberg M.A. (2003) Paleodiet studies using stable carbon isotopes from bone apatite and collagen: examples from Southern Ontario and San Nicolas Island, California. J. Anthrop. Archaeol. 22. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs I.R. (2020) Taking the Skeletons Out of The Closet: Contested Authority and Human Remains Displays in the Anthropology Museum (Bachelor’s Thesis). Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Justice N.D. (2002) Stone Age Spear and Arrow Points of California and the Great Basin. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Kerr S.L. (2004) The people of the southern Channel Islands: A bioarchaeological study of adaptation and population change in southern California. Doctoral Dissertation. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Knoeff R. & Zwijnenberg R., Eds. (2015) The Fate of Anatomical Collections. London, UK: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Morris S.L., Johnson J.R., Schwartz S.J., et al. (2016) The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 36(1):91-118.

- Overholtzer L. & Argueta J.R. (2018) Letting skeletons out of the closet: the ethics of displaying ancient Mexican human remains. International Journal of Heritage Studies 24(5):508-530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1390486. [CrossRef]

- Owsley D.W. & Jantz R.L. (2014) Kennewick Man: The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- Petaros A., Garvin H.M., Sholts S.B., et al. (2017) Sexual dimorphism and regional variation in human frontal bone inclination measured via digital 3D models. Leg Med (Tokyo) 29:53-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Petaros A., Sholts S.B., Cavka M., et al. (2021) Sexual dimorphism in mastoid process volumes measured from 3D models of dry crania from mediaeval Croatia. Homo 72(2):113-127. https://doi.org/10.1127/homo/2021/1243. [CrossRef]

- Rolle A.F. (1987) California: A History, 4th ed. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson Inc,.

- Shearer B.M., Sholts S.B., Garvin H.M. and Wärmländer S.K.T.S. (2012) Sexual dimorphism in human browridge volume measured from 3D models of dry crania: a new digital morphometrics approach. Forensic Sci Int 222(1-3):400 e401-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.06.013. [CrossRef]

- Sholts S.B. (2010) Phenotypic variation among ancient human crania from the northern Channel Islands of California: Reconstructing population history across the Holocene. Doctoral Dissertation. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Sholts S.B., Clement A.F. and Wärmländer S.K.T.S. (2010a) Additional Cases of Maxillary Canine-First Premolar Transposition in Several Prehistoric Skeletal Assemblages From the Santa Barbara Channel Islands of California. Amer. J. Phys. Anthrop. 143:155-160.

- Sholts S.B., Wärmländer S.K., Flores L.M., et al. (2010b) Variation in the measurement of cranial volume and surface area using 3D laser scanning technology. J Forensic Sci 55(4):871-876. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01380.x. [CrossRef]

- Sholts S.B. & Wärmländer S.K.T.S. (2012) Zygomaticomaxillary suture shape analyzed with digital morphometrics: reassessing patterns of variation in American Indian and European populations. Forensic Sci Int 217(1-3):234 e231-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.11.016. [CrossRef]

- Sholts S.S., Stanford D.J., Flores L.M. and Wärmländer S.K.T.S. (2012) Flake scar patterns of Clovis points analyzed with a new digital morphometrics approach: evidence for direct transmission of technological knowledge across early North America. Journal of Archaeological Science 39:3018-3026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.049. [CrossRef]

- Smith K.N., Wärmländer S.K.T.S., Vellanoweth R.L., et al. (2015) Residue analysis links sandstone abraders to shell fishhook production on San Nicolas Island, California. Journal of Archaeological Science 54:287-293. [CrossRef]

- Smith K.N., Vellanoweth R.L., Sholts S.B. and Wärmländer S.K.T.S. (2018) Residue analysis, use-wear patterns, and replicative studies indicate that sandstone tools were used as reamers when producing shell fishhooks on San Nicolas Island, California. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 20:502-505. [CrossRef]

- Stantis C., de la Cova C., Lippert D. and Sholts S.B. (2023) Biological anthropology must reassess museum collections for a more ethical future. Nat Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02036-6. [CrossRef]

- Swain H. (2016) Museum Practice and the Display of Human Remains. Archaeologists and the Dead – Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society. H. Williams and M. Giles. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- UNESCO (1970) Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

- Vellanoweth R.L. & Erlandson J.M. (1999) Middle Holocene Fishing and Maritime Adaptations at CA-SNI-161, CA-SNI-161, San Nicolas Island, California. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 21(2):257-274.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).