1. Introduction

The society shows a rapid growth in the proportion of women in the top management and entrepreneurship of companies and non-profit organizations. This growth in the number of female CEO and managers attracts the research attention about its outcome and performance in the workplace. Many women continue to be under-represented as leaders and senior managers worldwide. However, the role of women entrepreneurship draws the attention of previous studies for sustainable development[

1,

2]. Improvement in female entrepreneurial capacities increase women’s empowerment and reduce gender inequality for any entrepreneurship policy [

3,

4]. Female entrepreneurship is regarded as the country’s sustainable economic development to achieve UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) and gender equality for empowering all women involved.

Female entrepreneurship for the food sector can achieve of goals 8 “decent work and economic growth”, 9 “industry, innovation and infrastructure” and 12 “responsible consumption and production”. The food sector includes food sales, fast food, coffee shops, beverages, and restaurants and possess multi-faceted and complex set of challenges from farm to fork [

5,

6]. Akehurst, Simarro, & Mas-Tur [

7] and Mas-Tur & Ribeiro-Soriano [

8] indicates that women's businesses are usually concentrated in the services sector, especially in those activities in which they have traditionally had a greater presence such as retail, education, hospitality and personal assistance. United Nation emphasizes great importance to food sector in the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). Female entrepreneurship for the food sector achieves SDGs to promote sustainability by contributing economic growth and adequate consumption. However, there are many unanswered questions about women entrepreneurship policy instruments and empirical evidence regarding the potential for women entrepreneurship to contribute to sustainability performance.

The study observes which factors for women entrepreneurs with business success for achieving sustainable development. The factors of affecting the sustainability performance of women entrepreneurship are examined. The research aims to contribute to analyze women entrepreneurship from a gender perspective for making policy recommendation. In the sustainable development the policy instrument can promote and support women’s entrepreneurship as a means for by contributing economic growth and adequate consumption. This study fills this gap by examining what degree in a workplace affect women sustainability performance and investigating the characteristics of successful policy support.

Fernández; García-Centeno; Patier [

9]and Vracheva; Stoyneva [

10] compares the performance difference of businesswomen and businessmen to justify gender effect of female entrepreneurship study from the management theory. There are some economic sectors where women in management positions are usually better supported [

11,

12]. This study answers some research questions by investigating women entrepreneurs for the women’s entrepreneurship policy recommendations. Some studies can make women assistance policy recommendation such as the financial support, and marketing skills and business knowledge training [

13,

14]. Some studies also examine the challenges and barriers that the women workers face [

15,

16]. Although the issues of female entrepreneurs gain attention from the press and social media, previous studies focusing on women entrepreneurs for achieving policy recommendation are scare. The managerial implications and policy recommendation are provided for the women entrepreneurship research for achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

Feminist theory states that men and women is equal opportunity, but women for difficulty work environment because of lacking access to business networks or financial resources [

17,

18,

19]. Women face some barriers when they implement entrepreneurship plan or run a company. Therefore, gender differences examine economic power, social structure and class structure, but women's performance in business innovation, job creation, and economic growth is significant increase [

12,

20]. However, the gender heterogeneity of top management team for organizational performance findings are not conclusive [

21,

22].

Brush & Cooper [

23] recognize the need for a theoretical framework to examine women entrepreneurship and leadership. Some business model encompasses the ability of the women entrepreneurship [

24,

25]. Research progresses towards equality opportunities between men and women, but women is regarded as to take care of family and housework [

7,

26]. Women's entrepreneurship involves a complex process and challenge. In general, women entrepreneurship growth is especially high in developed countries if a government has adequate entrepreneurship assistance program and policy [

3,

9]. Therefore, there is no empirical study that examines whether women entrepreneurship has an impact on sustainability performance from the policy perspective.

2.2. Barrier and Women Entrepreneurship Capabilities

Entrepreneurship can help alleviate poverty, reduce environmental destruction and enhance education [

27,

28]. Women in the organization suffer from the glass ceiling level and major barriers to advance to the entrepreneurship management [

29,

30,

31]. Women entrepreneurship is important for economic growth [

32,

33,

34] and sustainable development [

25,

35]. Women entrepreneurship issues include gender differences, motivation and barriers for business start-up [

9,

14,

36] and examine success factors for women entrepreneurs [

37,

38].

Barriers obstruct women entrepreneurship, so the examination of women entrepreneurship’s barrier is important in the women entrepreneurship research [

39,

40]. Entrepreneurship capabilities are essential function of management for women. Women entrepreneurship capabilities can be developed in the process of entrepreneurship training and learning [

41]. Women entrepreneurship capabilities refers to develop the capabilities of detecting business opportunities, acting in uncertain environment and solving problem [

41,

42]. Female entrepreneurs can overcome some barriers for establishing their own firm and develop their capabilities. Therefore, it is important to identify the extent and context of barrier in women entrepreneurship research. To understand the barriers factors for women entrepreneurship is a research gap to be explored for implementing policy recommendation. Therefore,

H1 : Barrier has a negative effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities.

2.3. Family Support and Women Entrepreneurship Capabilities

Gender is an important performance difference variable for the women entrepreneurship research [

43,

44]. Although some progress of gender equality in business environment, it is important to examine gender performance differences for women entrepreneurship research [

10,

40]. The theoretical background relates to family researches such as the work–family balance perspective [

20,

41], the work–family interface perspective [

21,

46] and family support[

48,

49].

Women entrepreneurs may face some additional challenges such as family support and work–family responsibility [

46,

49]. Thus, women make efforts to enhance family support for entrepreneurship capabilities improvement. Many of the research focuses on female entrepreneurship, but there is a paucity of family support research in this women entrepreneurship area. Female entrepreneurs are engaged in work and family [

50,

51]. Female entrepreneurs may obtain family support that improve female entrepreneurship capabilities. For a better understanding of how family support affects women entrepreneurship capabilities, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2 : Family support has a positive effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities.

2.4. Motivation and Women Entrepreneurship Capabilities

Women entrepreneurs are motivated by economic factors, and they often adopt entrepreneurship for opportunities development [

45,

52]. To understand the motivation factors for women entrepreneurship is a research agenda to be explored for implementing policy recommendation. The motivation research construct can drive different women entrepreneurship capabilities [

53,

54]. In general, motivation can positively influence women entrepreneurship capabilities. Women entrepreneurs with high level of motivation may become more confident in develop or enhance women entrepreneurship abilities [

55,

56]. Ultimately, motivation may increase women entrepreneurship capabilities to make strategic decisions, and obtain desired performance. However, few studies examine whether motivation enhance women entrepreneurship and sustainable performance from a gender perspective. Therefore,

H3: Motivation has a positive effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities.

2.5. Barrier and Sustainability Performance

Wood,Ng, Bastian[

57] develops sustainability performance dimensions and indicators for organizations’ sustainable policy implementation. Sustainable performance consists of environmental and financial performances [

58,

59,

60]. Previous study composes sustainable performance frameworks including environmental and social performance to increase market share, enhance brand image, foster the quality of the product or service and drive financial performance [

61]. However, corporate sustainable performance is hardly assessed in practice [

59,

62]. Sustainability performance is increasingly becoming a hot topic in the field of service industry [

63,

64]. Sustainability performance includes national economic growth, global environmental protection and social responsibility [

65,

66,

67]. The research examining whether women entrepreneurship have contributed to achieving sustainability performance. Therefore, this study considers sustainability performance dimensions of women entrepreneurship for the food sector to achieve SDGs including female entrepreneurship can achieve of goals 8 “decent work and economic growth”, 9 “industry, innovation and infrastructure” and 12 “responsible consumption and production”.

Examining the role of women entrepreneurship is increasing, but barriers research on women entrepreneurs assistance program and policy is scarce [

18,

68]. Performance difference in companies exists between women and men [

36]. Watson [

69] find that women’s job performance tends to underperform from revenues, profitableness and sales in comparison to men’s job performance. Langowitz & Minniti [

70] examine the performance differences in women entrepreneurship and finds mixed results on performance difference with barriers in entrepreneurship. Barriers may hinder women entrepreneurs from becoming more performance [

71,

72]. This issue implies that women have less access to entrepreneurial capital, knowledge and networks to conduct their businesses, which results in under-performance. However, previous studies concern with the role of women entrepreneurship for sustainability development [

2,

30,

31], but few studies examine barriers for women entrepreneurship issues. Therefore,

H4: Barrier has a positive effect on sustainability performance.

2.6. Family Support and Sustainability Performance

Family support is very an important factor for enhancing better performance [

29]. Women entrepreneurship with family support are regarded as business-to-family interference[

74]. In general, women entrepreneurs often need to deploy their energy and time into several roles, which reduces the possibility to succeed in a company [

75,

76]. Therefore, women entrepreneurship with family support can achieve a competitive advantage[

49,

77]. The role of family support affects the business skills, education, and performance of women entrepreneurship. The family support may strengthen the women’s sustainable performance.

H5: Family support has a positive effect on sustainability performance.

2.7. Motivation and Sustainability Performance

The previous literature finds the relationship between motivation and performance [

78,

79]. Motivation are the most significant considerations for the performance of women entrepreneurs. Despite the growth in entrepreneurship research about women, few studies examine whether motivation enhance sustainable performance from a gender perspective. Previous research has identified motivation drives women entrepreneurship towards the role of sustainable development [

9,

14,

80]. Motivation boosts the level of positive performance. The positive motivation can help women entrepreneurs cope with better performance. As a result, positive motivation may have better performance consequences.

H6: Motivation has a positive effect on sustainability performance.

2.8. Women Entrepreneurship Capabilities and Sustainability Performance

Green entrepreneurship drives a company to create business competitive advantage [

81]. Policy recommendation for women entrepreneurs is to help more women engage in entrepreneurial activity for achieving the sustainability performance. However, entrepreneurship policy instruments may be biased and do not take into consideration women face in different entrepreneurial environment contexts [

4,

15]. However, many countries fail to implement women entrepreneurship policy and offer few or no programs that operationalize their policy. Policy are identified as an important research of the entrepreneurial ecosystem [

10,

82,

83,

84] Hopefully, the research purpose of women entrepreneurship policy can offer valuable insights from policy perspectives to offer potential policy solution and link policy recommendation instruments for women entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Women entrepreneurship capabilities play an important role in ensuring business success [

85,

86]. Despite many problems, women entrepreneurship capabilities have become imperative for the sustainability performance. Women entrepreneurs with entrepreneurship capabilities can attain high market value and business growth [

87,

88]. Women entrepreneurs are more in innovative concept by enhance entrepreneurship capacities to develop sustainable business[

89]. Women entrepreneurs needs to develop entrepreneurship capabilities to identify new market opportunities and seek recognition for better performance [

90,

91]. Thus, women entrepreneurship capabilities may affect the performance positively. Therefore,

H7: Women entrepreneurship capabilities have a positive effect on the sustainability performance.

3. Research Methodology

The research tests an empirical model on the basis of research variables and constructs by employing SEM approach. The research objective is to develop an empirical model to study and measure research constructs in women entrepreneurship and sustainability performance from entrepreneurship policy perspectives. Personal interviews are conducted with a convenient sample of 20 participants of women entrepreneurs in Taiwan. Through this step, participants are ensured of personal anonymity and confidentiality of the information shared during voluntary interviews.

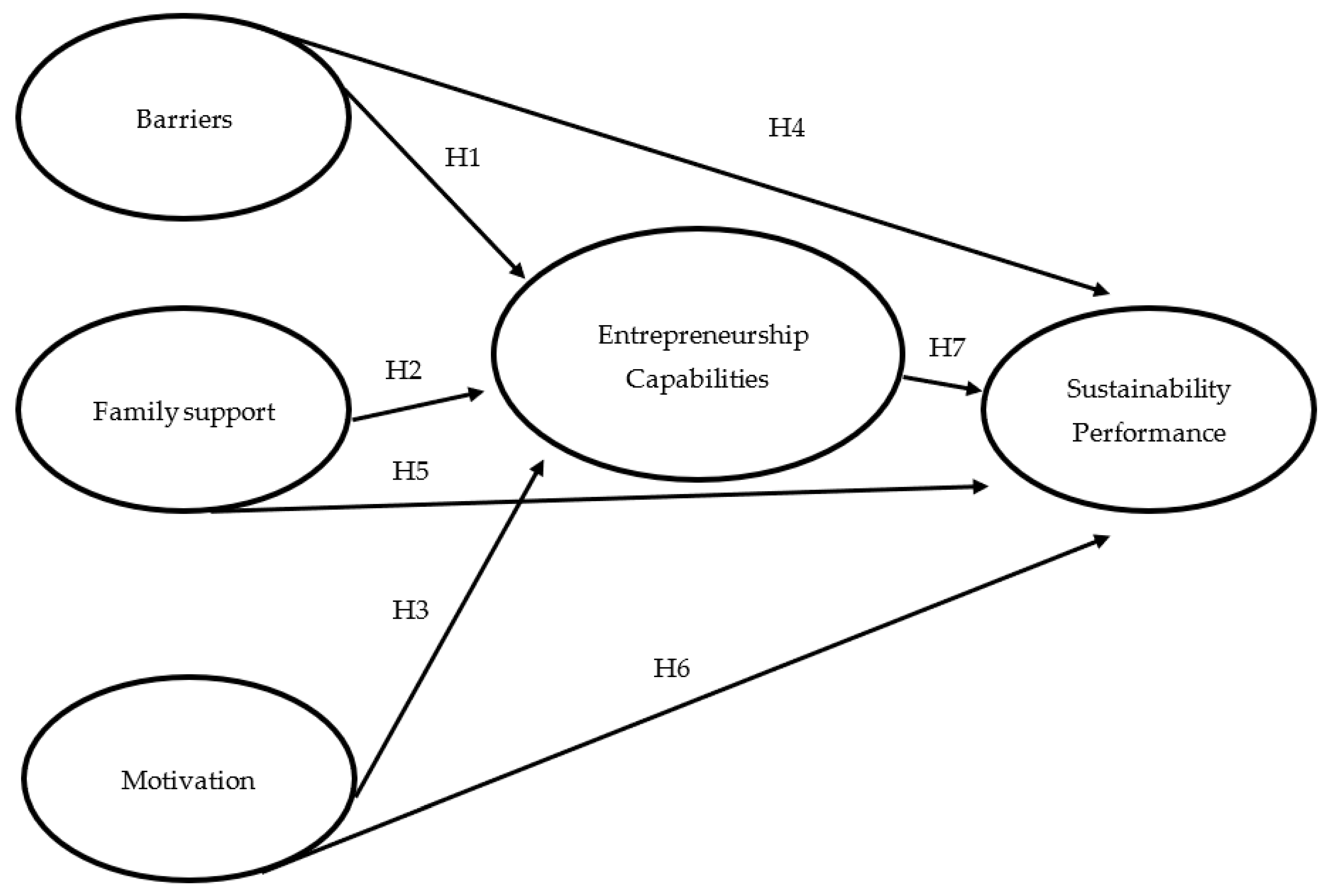

After finishing personal interview, an integrative model draws on these sets of sustainability performance antecedent factors including barriers, family support, motivation and women entrepreneurship capabilities from policy perspective. The research purpose is to examine the characteristics of successful women entrepreneurship policy and to develop an empirical model to measure variables relative to the sustainability performance of women entrepreneurship for implementing policy support and recommendation. Questionnaire is designed after personal interview, literature review and pilot study. The questionnaires are pre-tested composed of women entrepreneurs to clarify or eliminate misleading or ambiguous questions before final distribution, which is modified. This study collects data from women entrepreneurs in Taiwan for engaging in food industry. Women entrepreneurs are surveyed by using online questionnaire containing items dealing with barriers, family support, motivation, entrepreneurship capabilities, and performance. All questionnaire items measure women entrepreneurs’ perceptions on seven-point scale. The study employs SEM to test hypotheses. After reviewing the management literature and conducting a preliminary pre-test study with 20 participants, this study examines five groups of research constructs: barriers, family support, motivation, entrepreneurship capabilities, and performance. (please see

Figure 1).

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The study obtains 175 usable questionnaires from online survey. Married status (60%) outnumber Single (38%), and 35% are between the ages of 41 to 50. For the education status of respondents, 49% of respondents have undergraduate degrees and 31% of respondents have a master’s degree or higher and 15% of respondents have a senior high school degree. Regarding to respondents’ entrepreneurship experience, 41% of respondents have 5 to 10 years; 37 % of respondents have 6 to 9 under 5 years and 16% of respondents have 11 to 15 years. 46% of women entrepreneurs manage coffee shop followed by managing beverage(26%). Most company size are under 10 employees (58%) and 11-50 employee (20%).

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the women entrepreneur sample.

4.2. Measurement Model

Table 2 provides the questionnaire items, mean value, and standard deviations of research constructs in the measurement model outputs. The measurement model shows that 24 standardized loadings are high and have t-values with significant (p < 0.01).

The adequacy of the measurement model tests reliability (Cronbach’s alpha), convergent validity, and discriminant validity. This study examines a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability analysis for all the constructs (barriers, family support, motivation, women entrepreneurship capabilities, and sustainability performance). The empirical results indicate that composite construct reliability values and composite reliabilities exceed the threshold of 0.70 with adequate composite reliability. Average variance extracted (AVE) values shows indicators’ degree of shared representation with the constructs. The lowest value for average variance extracted is 0.63 with the convergent validity of the measures. The convergent validity of and discriminant validity for all research constructs are shown in

Table 3.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assesses the good-of-fit of the measurement. As a result, CFA is a good fit for the data collection((χ2 = 459.47, df = 174, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.93 , GFI = 0.91). Overall fit indices for the models show in

Table 4. The chi-squared test yields values of 459.47 for samples with 74 degrees of freedom, p = .00. Chi-squared values, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (0.055), goodness of fit index(GFI)(0.91), comparative fit index (CFI) (0.92) and normed fit index (NFI) (0.93) is adequate to assess model fit. Fit indices yield values that support a good model fit for the dataset.

4.3. Structural Model

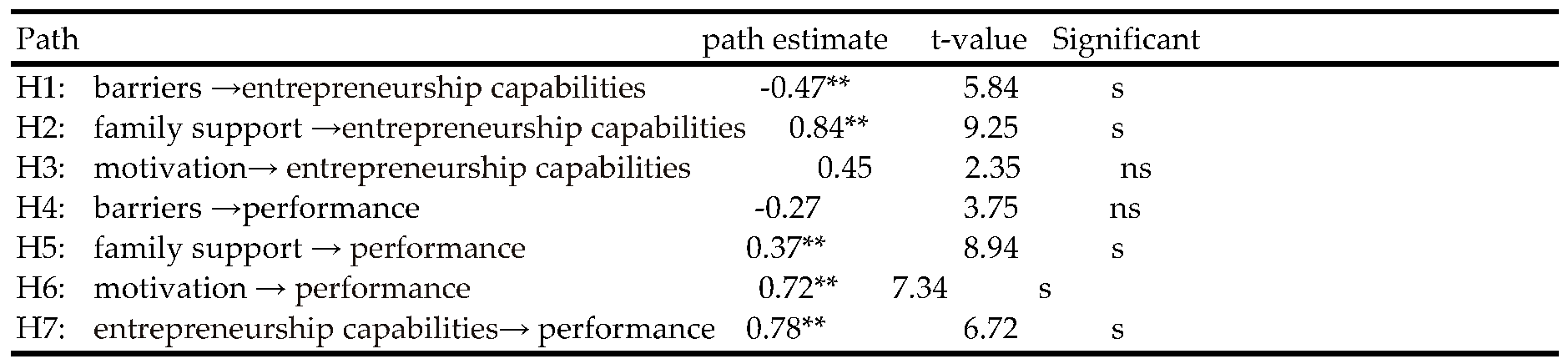

The result of each research hypothesis examines the causal relationship among research constructs is presented in

Figure 1.

Table 5 presents results of analyses of the SEM path coefficients in the structural model describing the relationships among constructs. Research results support 5 hypotheses: barrier has a negative effect on entrepreneurship capabilities(H1)( (β = -0.47, t = 5.84, p = 0.000); family support has a positive effect on entrepreneurship capabilities (H2)( β = 0.76, t = 7.47, p = 0.000); family support has a positive effect on performance(H5) (β = 0.37, t = 4.15, p = 0.000); motivation has a positive effect on performance (H6) (β = 0.72, t = 7.34, p = 0.000) and entrepreneurship capabilities have a positive effect on the performance (H7) (β = 0.78, t = 6.72, p = 0.000). Motivation has a positive effect on entrepreneurship capabilities (H3) and barrier has a negative effect on performance (H4) is not supported from the research.

5. Discussion

This study proposes as a foundation for a conceptual model of women entrepreneurship capabilities and sustainability performance in the food sector for achieving achieve policy recommendation. The results of this study show that family support and motivation have a significantly positive effect on female entrepreneurship capabilities while barrier has a significantly negative effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities. The research finds that family support and motivation have positive and significant effects on sustainability performance while barrier has no significant effect on sustainability performance. Thus, women entrepreneurship capabilities have a positive and significant effect on sustainability performance.

The findings of the study have several implications for women entrepreneurs in the food sector for policy support. The research finds that family support and motivation affect women entrepreneurship capabilities and sustainability performance. Family support includes family organizational support, family moral support and family financial support. Motivation reflects to develop my business capabilities, to be professional independence from my boss, to take on the risks and challenges, to be encouragement of government, to contribute something useful to society and to seek greater recognition. Accordingly, women entrepreneurs in the food sector have higher family support and motivation with high possibility of success. Particularly, women with higher entrepreneurship capabilities have better sustainability performance. Women entrepreneurship capabilities, family support and motivation are important determinant of success in the food sector. In terms of managerial practice, the finding suggests that government or firm should overcome the barrier and stimulate the motivation for the women entrepreneurs. Significantly, government should have policy operations in stimulating the women motivation and enhance the women entrepreneurship capabilities for achieving better performance.

Barrier has a negative effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities including ability to detect business opportunities, ability to act in uncertain environments, ability to solve problems, ability to be leadership, ability to communication and ability to manage, which suggests that barriers including lacking of business training, difficulty in obtaining financing, difficulty in obtaining subsidies, gender discrimination and high level of competition affect the women entrepreneurship capabilities in the food sector. The research results confirm and extend Shen, Sha and Wu[

22] and Costache et al’s[

39] results. These studies claim that barrier has a negative effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities. When women will start new business or implement entrepreneurship plan to overcome the barriers under policy support.

Family support has a positive effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities, which poses that family support has a positive effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities in a different way including family organizational support, family moral and financial support because women and men have different roles in the family [

48,

49]. Additionally, the results indicate that women tend to start business have barriers including lacking of business training, difficulty in obtaining financing, difficulty in obtaining subsidies, gender discrimination and high level of competition. Women actively seek family support and overcoming barriers for entrepreneurship. The results indicate that gender equality policies can be working but still are not enough for developing women entrepreneurship abilities.

Women entrepreneurship policy is recommended to provide more business training, offer some finance support or subsidies, give incentives for women entrepreneurs. The policy support also can offer some family financial or non-financial support for women entrepreneurs. Government can be recommended to encourage women entrepreneurs’ motivation to develop some entrepreneurship motivation such as offer some women entrepreneurship training courses, financial support, child care program. The research aims to contribute to analyze women entrepreneurship from a gender perspective for making policy recommendation for women entrepreneurship assistance program. In the sustainable development the policy tool can promote and support women’s entrepreneurship as a means for by contributing decent work and economic growth, creating industry, innovation and infrastructure and guaranteeing responsible consumption and adequate production. The research results are consisted with the previous studies that women entrepreneurship growth is especially high if a government has adequate entrepreneurship assistance program and policy [

3,

9,

71].

6. Conclusions and Research Limitations

The research fills the research gap for the women entrepreneurship and sustainability performance for examining key successful factors for the women entrepreneurship. The research purpose is to investigate these factors affect women entrepreneurship capabilities and sustainability performance by using SEM analysis. This research employs online and mail survey and obtains 175 women entrepreneur sample. The study finds that family support and motivation have positive effect on women entrepreneurship capabilities and sustainability performance. Barriers have no effect on performance. Hopefully, the research can provide the guidance to contribute to women’s entrepreneurship opportunities for policy support.

Although contributing the existing sustainability literature, this study has several research limitations. First, his study surveys only female entrepreneurs in the food sector in Taiwan, and the findings may be not generalizable to other countries and industries. Further research can test other research constructs of female entrepreneurs in other countries and various industries. Second, the size of the women entrepreneurship sample is small. Further women entrepreneurship research for policy development needs more resources to increase the sample size for various firms or industries. Third, women entrepreneurship may be observed on the long-term strategic behavior to sustainability performance changes over a one-year period, so future research should adopt a longitudinal design to test the causal relationship for women entrepreneurship in the policy support issues. Finally, not at all research variables and construct are measured and conceptualized in the research model, further research should explore the effect of other external and internal factors of women entrepreneurs for policy instrument evaluation.

Funding

Please add: The author acknowledges and is grateful for the financial support the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant 107-2410-H-005-019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges and is grateful for the financial support the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant 107-2410-H-005-019. Thank for may administrative and technical support and financial aid.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Qahtani, M.; Zguir, M.F.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Women entrepreneurship for sustainability: Investigations on status, challenges, drivers, and potentials in Qatar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.L.; Metcalfe, B.D.; Zali, M.R. Gender inequality: Entrepreneurship development in the MENA region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Barraza, N.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.F.; Salazar-Sepulveda, G.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Entrepreneurial intention: A gender study in business and economics students from Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Coleman, S.; Foss, L.; Orser, B.J.; Brush, C.G. Richness in diversity: Towards more contemporary research conceptualisations of women’s entrepreneurship. Int. Small Bus. J. 2021, 39, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual models of food choice: Influential factors related to foods, individual differences, and society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pounds, A.; Kaminski, A.M.; Budhathoki, M.; Gudbrandsen, O.; Kok, B.; Horn, S.; Malcorps, W.; Mamun, A.-A.; McGoohan, A.; Newton, R.; et al. More than fish—Framing aquatic animals within sustainable food systems. Foods 2022, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akehurst, G.; Simarro, E.; Mas-Tur, A. Women entrepreneurship in small service firms: Motivations, barriers and performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 2489–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, A.; Soriano, D.R. The level of innovation among young innovative companies: The impacts of knowledge-intensive services use, firm characteristics and the entrepreneur attributes. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.B.; García-Centeno, M.D.C.; Patier, C.C. Women sustainable entrepreneurship: Review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vracheva, V.; Stoyneva, I. Does gender equality bridge or buffer the entrepreneurship gender gap? A cross-country investigation. Int. J. Entre. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1827–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H. Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgheib, P. Multi-level framework of push-pull entrepreneurship: Comparing American and Lebanese women. Int. J. Entre. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orser, B.J.; Riding, A.L.; Manley, K. Women entrepreneurs and financial capital. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, L.M.; Bobek, V.; Horvat, T. Determinants of success of businesses of female entrepreneurs in Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguía, A.; Wach, D.; Garcia-Ael, C.; Moriano, J.A. Think entrepreneur – think male”: The effect of reduced gender stereotype threat on women's entrepreneurial intention and opportunity motivation. Int. J. Entre. Behav. Res. 2019, 28, 1001–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.R. The link between women entrepreneurship, innovation and stakeholder engagement: A review. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 63, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Rahman, M.; Radicic, D. Women entrepreneurship in international trade: Bridging the gap by bringing feminist theories into entrepreneurship and Internationalization Theories. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calás, M.B.; Smircich, L.; Bourne, K.A. Extending the boundaries: Reframing “entrepreneurship as social change” through feminist perspectives. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2009; 34, 552–569, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27760019. [Google Scholar]

- Melero, E. Are workplaces with many women in management run differently? J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinidis, C.; Lebègue, T.; El Abboubi, M.; Salman, N. How families shape women’s entrepreneurial success in Morocco: An intersectional study. Int. J. Entre. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1786–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Marti, A.; Porcar, A.T.; Mas-Tur, A. Linking female entrepreneurs’ motivation to business survival. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Sha, Z.; Wu, Y.J. Enterprise adaptive marketing capabilities and sustainable innovation performance: An opportunity– resource integration perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Cooper, S.Y. Female entrepreneurship and economic development: An international perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, K.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J. A theoretical framework on the determinants of food purchasing behavior of the elderly: A bibliometric review with scientific mapping in Web of Science. Foods 2021, 10, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdousi, F.; Mahmud, P. Role of social business in women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: Perspectives from Nobin Udyokta projects of Grameen Telecom Trust. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, K.; Ahmad, N.; Naveed, R.; Scholz, M.; Adnan, M.; Han, H. The impact of work–family enrichment on subjective career success through job engagement: A case of banking sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Vinuesa, R.; Nedungadi, P. Bibliometric analysis of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 studies from India and connection to sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.; Bosma, N.; Stam, E. Advancing public policy for high-growth, female, and social entrepreneurs. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baixauli-Soler, J.S.; Belda-Ruiz, M.; Sanchez-Marin, G. Executive stock options, gender diversity in the top management team, and firm taking. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, M.; Pinto, L.H.; Olveira Blanco, A.; Cancelo, M. Female entrepreneurship: Can cooperatives contribute to overcoming the gender gap? A Spanish first step to equality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Barraza, N.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.F.; Salazar-Sepulveda, G.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Entrepreneurial intention: A gender study in business and economics students from Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggesi, S.; Mari, M.; de Vita, L.; Foss, L. Women entrepreneurship in STEM fields: Literature review and future research avenues. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Kaleem, N.; Chani, M.I.; Ahmed, M. Worldwide role of women entrepreneurs in economic development. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setini, M.; Yasa, N.N.K.; Supartha, I.W.G.; Giantari, I.K.; Rajiani, I. The passway of women entrepreneurship: Starting from social capital with open innovation, through to knowledge sharing and innovative performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.L.; Metcalfe, B.D.; Zali, M.R. Gender inequality: Entrepreneurship development in the MENA region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R.W.; Robb, A.M. Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 8, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado-Gomis, A.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.-A.; Cervera-Taulet, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Women as key agents in sustainable entrepreneurship: A gender multigroup analysis of the SEO-performance relationship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, D.; Vasile, V.; Oltean, A.; Comes, C.A.; Stefan, A.-B.; Ciucan-Rusu, L.; Bunduchi, E.; Popa, M.-A.; Timus, M. Women entrepreneurship and sustainable business development: Key findings from a SWOT–AHP analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, C.; Dumitrascu, D.D.; Maniu, I. Facilitators of and barriers to sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises: A descriptive exploratory study in Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, A.; Soriano, D.R. The level of innovation among young innovative companies: The impacts of knowledge-intensive services use, firm characteristics and the entrepreneur attributes. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuwari, M.M.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Asking the right questions for sustainable development goals: Performance assessment approaches for the Qatar education system. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauceanu, A.M.; Rabie, N.; Moustafa, A.; Jiroveanu, D.C. Entrepreneurial leadership and sustainable development—A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Pathak, S.; Wennberg, K. Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 334–362, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23434167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.; Santos, A.; Ribeiro, M.; Chambel, M. Please do not interrupt me: Work–family balance and segmentation behavior as mediators of boundary violations and teleworkers’ burnout and flourishing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.A.; Barnes, C.M. A multilevel field investigation of emotional labor, affect, work withdrawal, and gender. Acad. Manage. J. 2011, 54, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; McDougal, M.S. Work–family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2007, 32, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Zhao, X. Employees' work–family conflict moderating life and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T.; Yirci, R.; Papadakis, S. Exploring the interrelationship between COVID-19 Phobia, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and life satisfaction among school administrators for advancing sustainable management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Moghaddam, K.; Cloninger, P.; Cullen, J. A cross-national study of youth entrepreneurship: The effect of family support. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Lenka, U.; Singh, K.; Agrawal, V.; Agrawal, A.M. A qualitative approach towards crucial factors for sustainable development of women social entrepreneurship: Indian cases. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Liang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, W. Science mapping: A bibliometric analysis of female entrepreneurship studies. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 36, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrachina Fernández, M.; García-Centeno, C.; Calderón Patier, C. Women sustainable entrepreneurship: Review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Pita, M. Appraising entrepreneurship in Qatar under a gender perspective. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2020, 12, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović-Pantić, S.; Semenčenko, D.; Vasilić, N. Women entrepreneurship in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Serbia. J. Women’s Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A.; Brush, C.G.; Welter, F. Advancing a framework for coherent research on women's entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.G.; Park, D. A few good women—On top management teams. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.P.; Ng, P.Y.; Bastian, B.L. Hegemonic conceptualizations of empowerment in entrepreneurship and their suitability for collective contexts. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletic, M.; Maletic, D.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomiscek, B. Sustainability exploration and sustainability exploitation: From a literature review towards a conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletic, M.; Maletic, D.; Dahlgaard, J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomiscek, B. Do corporate sustainability practices enhance organizational economic performance? Int. J. Qual. Serv. 2015, 7, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshiaba, S.M.; Wang, N.; Ashraf, S.F.; Nazir, M.; Syed, N. Measuring the sustainable entrepreneurial performance of textile-based small–medium enterprises: A mediation–moderation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Roy, M.J. Sustainability in action: Identifying and measuring the key performance drivers. Long-range planning 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Elmagrhi, M.H.; Rehman, R.U.; Ntim, C.G. Environmental management practices and financial performance using data envelopment analysis in Japan: The mediating role of environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. The link of environmental and economic performance: Drivers and limitations of sustainability integration. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, C.C.; Skaggs, B.C.; Pearce, C.L.; Wassenaar, C.L. Serving one another: Are shared and self-leadership the keys to service sustainability? J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.N.; de Carvalho, M.M. A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.; Babar, M.; Irfan, M.; Liren, A. Impact of environmental, social values and the consideration of future consequences for the development of a sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, A.; Huang, J.; Dreher, G.F. Mentoring across culture: The role of gender and martial status in Taiwan and the US. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2542–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Comparing the performance of male and female controlled businesses: Relating outputs to inputs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langowitz, N.; Minniti, M. The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hakim, G.; Bastian, B.L.; Ng, P.Y.; Wood, B.P. Women’s empowerment as an outcome of NGO projects: Is the current approach sustainable? Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, S.; Singh, W.; Suresh, V.; Rashed, T.; Uppaal, K.; Nair, R.; Bhavani, R.R. A priority action roadmap for women’s economic empowerment (PARWEE) amid COVID-19: A co-creation approach. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2021, 13, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, I.S.B.A.; Chan, V.; Chan, C. The Determinants factors of womenpreneurship performances in low economic class: An evidence from Melaka. Int. J. Entrep. Bus. Creat. Econ. 2021, 1, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolova, T.S.; Brush, C.G.; Edelman, L.F.; Elam, A. Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, M.; Johal, R.K. Rural women entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and beyond. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 18, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, G.; Cukier, W.; Gagnon, S. (In)visibility in the margins: COVID-19, women entrepreneurs and the need for inclusiverecovery. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, W.; Chavoushi, Z.H. Facilitating women entrepreneurship in Canada: The case of WEKH. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Jimenez, R.; Hernández-Ortiz, M.J.; Fernández, A.I.C. Gender diversity influence on board effectiveness and business performance. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Naz, S.; Akhtar, S.; Abreu, A. Linking entrepreneurial orientation with innovation performance in SMEs; the role of organizational commitment and transformational leadership using smart PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E.; Shamah, R. Determinants of women entrepreneurs’ firm performance in a hostile environment. J. Bus.Res. 2018, 88, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Ntanos, S.; Galatsidas, S.; Arabatzis, G.; Chalikias, M.; Kalantonis, P. The mediating role of firm strategy in the relationship between green entrepreneurship, green innovation, and competitive advantage: The case of medium and large-Sized firms in Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Mason, C. Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Bus Econ. 2017, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, D.; Yıldırım, N. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Mapping the business landscape for the last 20 years. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertello, A.; Battisti, E.; De Bernardi, P.; Bresciani, S. An integrative framework of knowledge–intensive and sustainable entrepreneurship in entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A.A.; Van Riel, A.C.R.; Essers, C. What drives ecopreneurship in women and men?—A structured literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.M.; Morillas, L.; Martins-Loução, M.A.; Cruz, C. Women’s empowerment, research, and management: Their contribution to social sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalan, M.; Bastian, B.L.; Viswanathan, P.K. The role of multi-actor engagement for women’s empowerment and entrepreneurship in Kerala, India. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, A.M.; Jayawarna, D. Bios, mythoi and women entrepreneurs: A Wynterian analysis of the intersectional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-employed women and women-owned businesses. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Women entrepreneurship: A systematic review to outline the boundaries of scientific literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermundsdottir, F.; Aspelund, A. Competitive sustainable manufacturing-Sustainability strtaegies, environmental and social innovations, and their effects on firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Khursheed, A.; Fatima, M.; Rao, M. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2021, 13, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).