Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

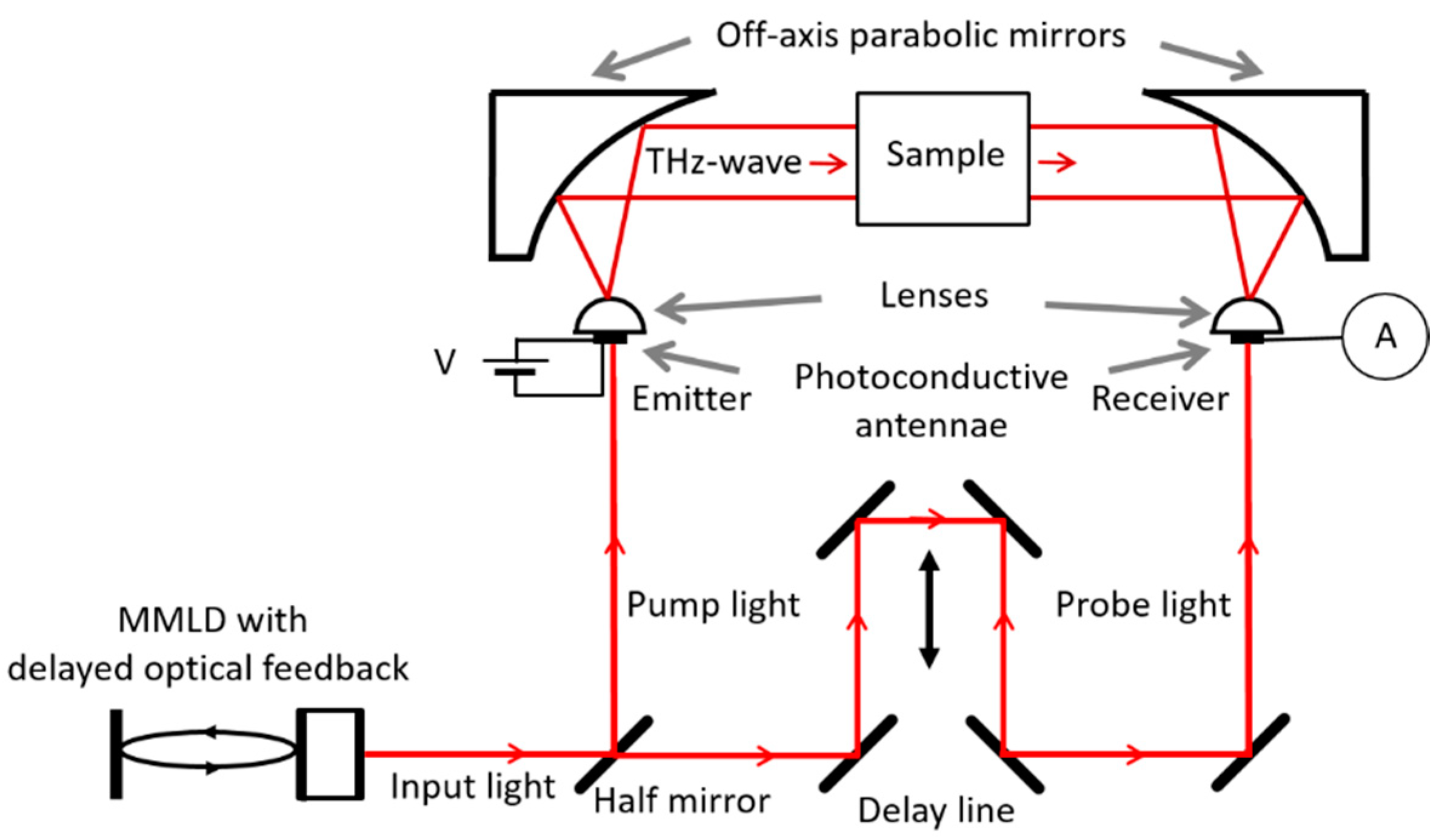

2. Methods

2.1. Rate Equations for a Multimode Laser Diode with Delayed Optical Feedback

2.2. Simulation Model for THz Time-Domain Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussion

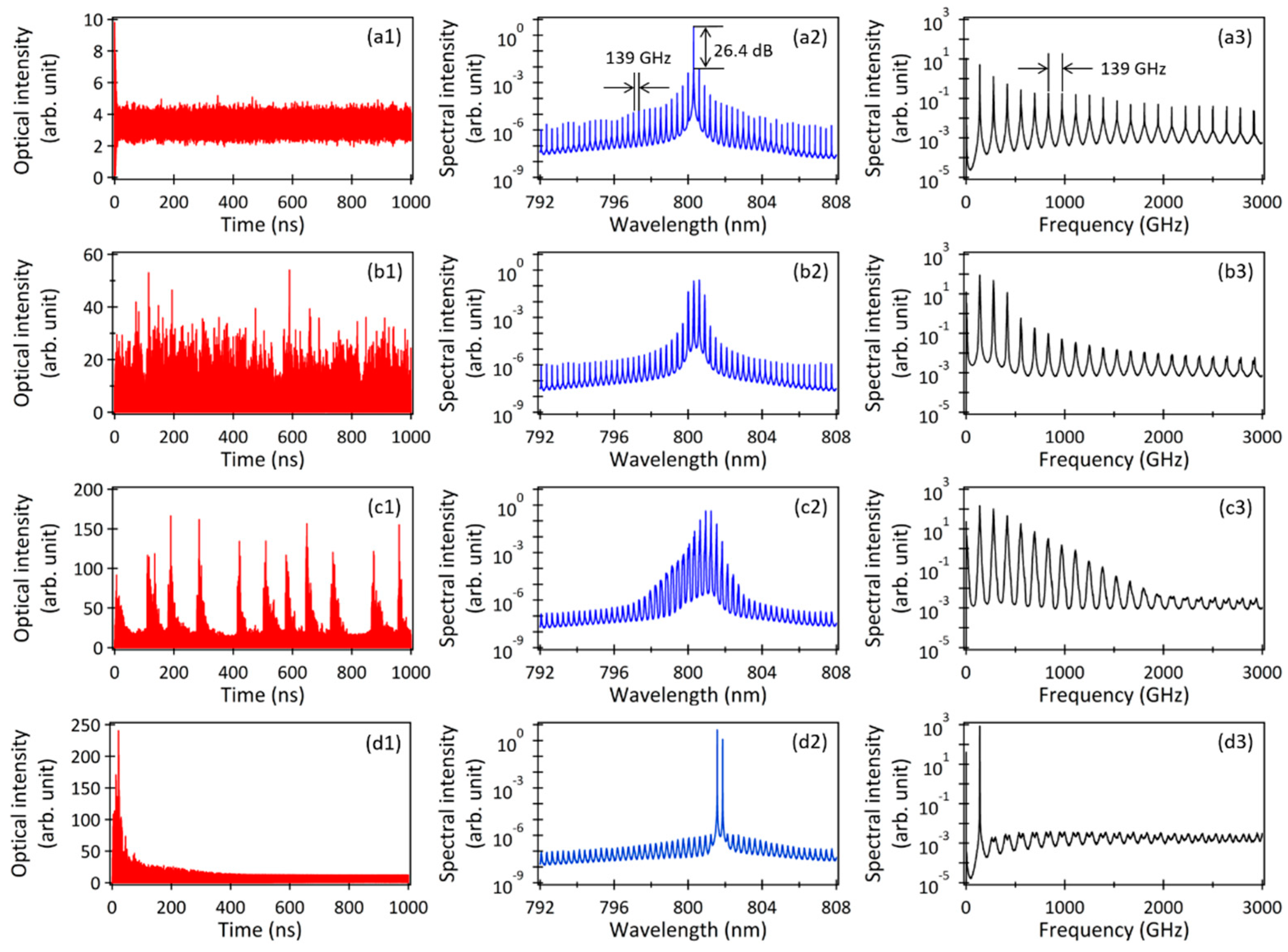

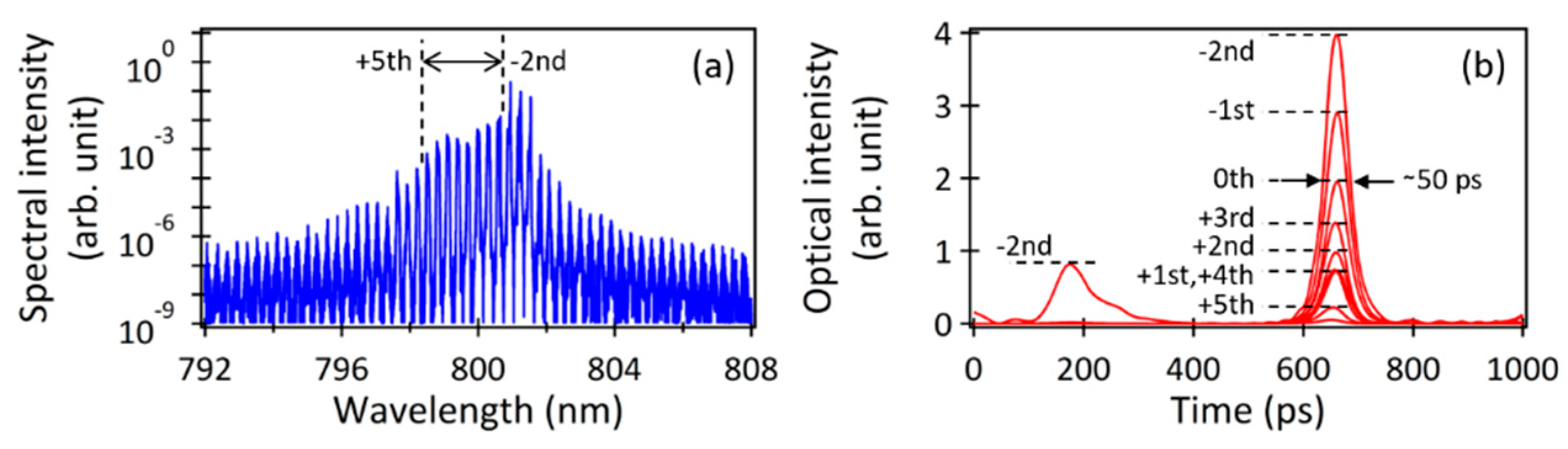

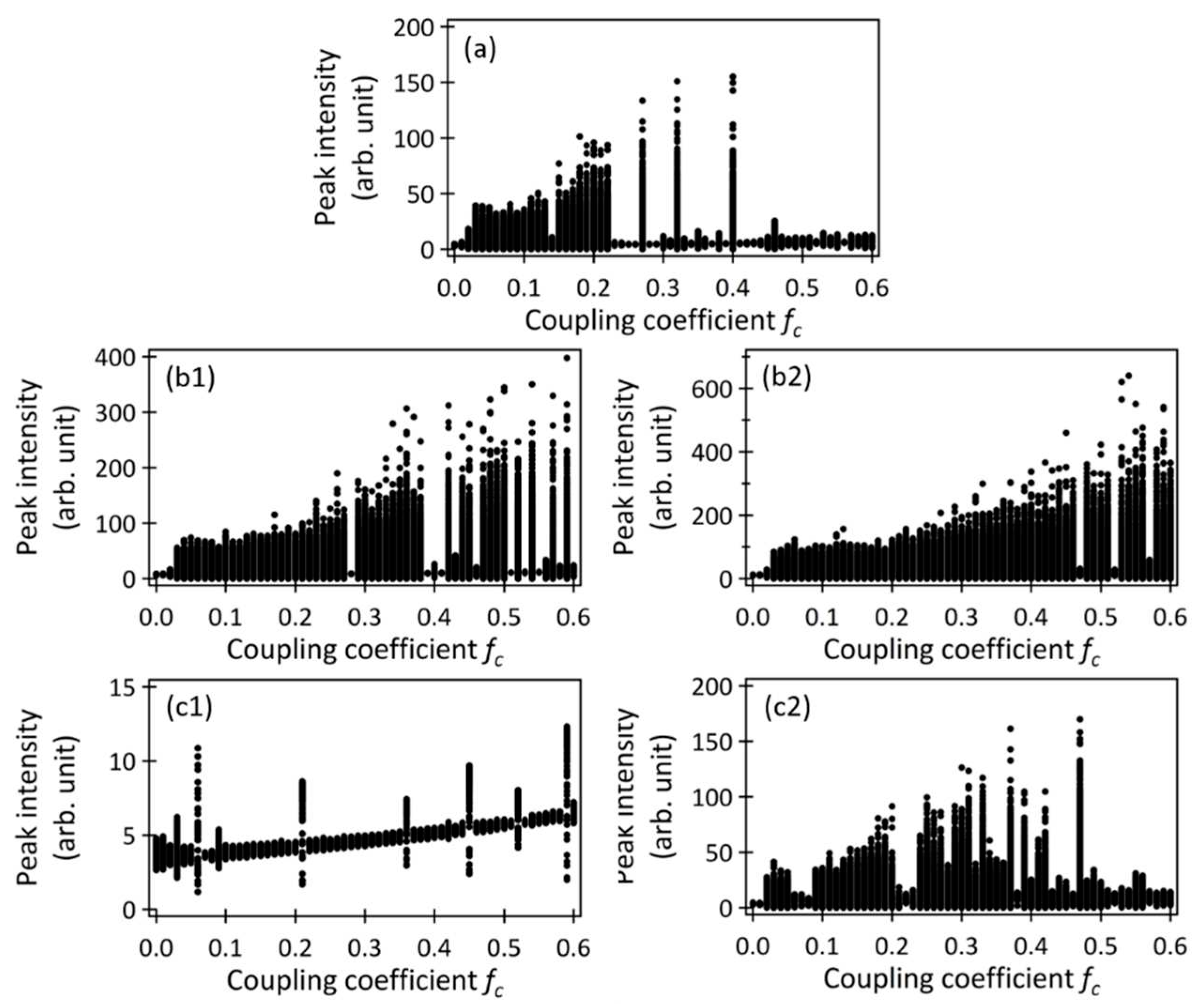

3.1. Classification of LD Oscillation State by the Coupling Coefficient of Optical Feedback

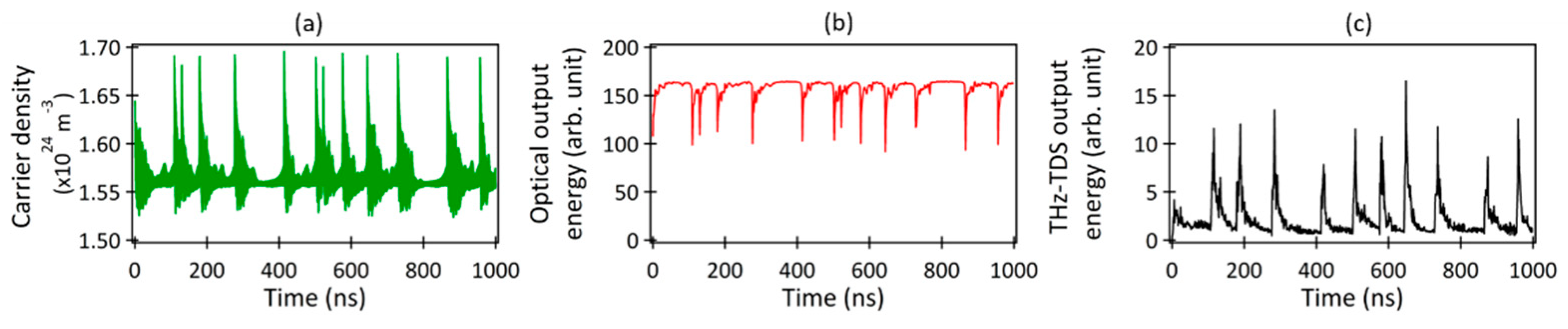

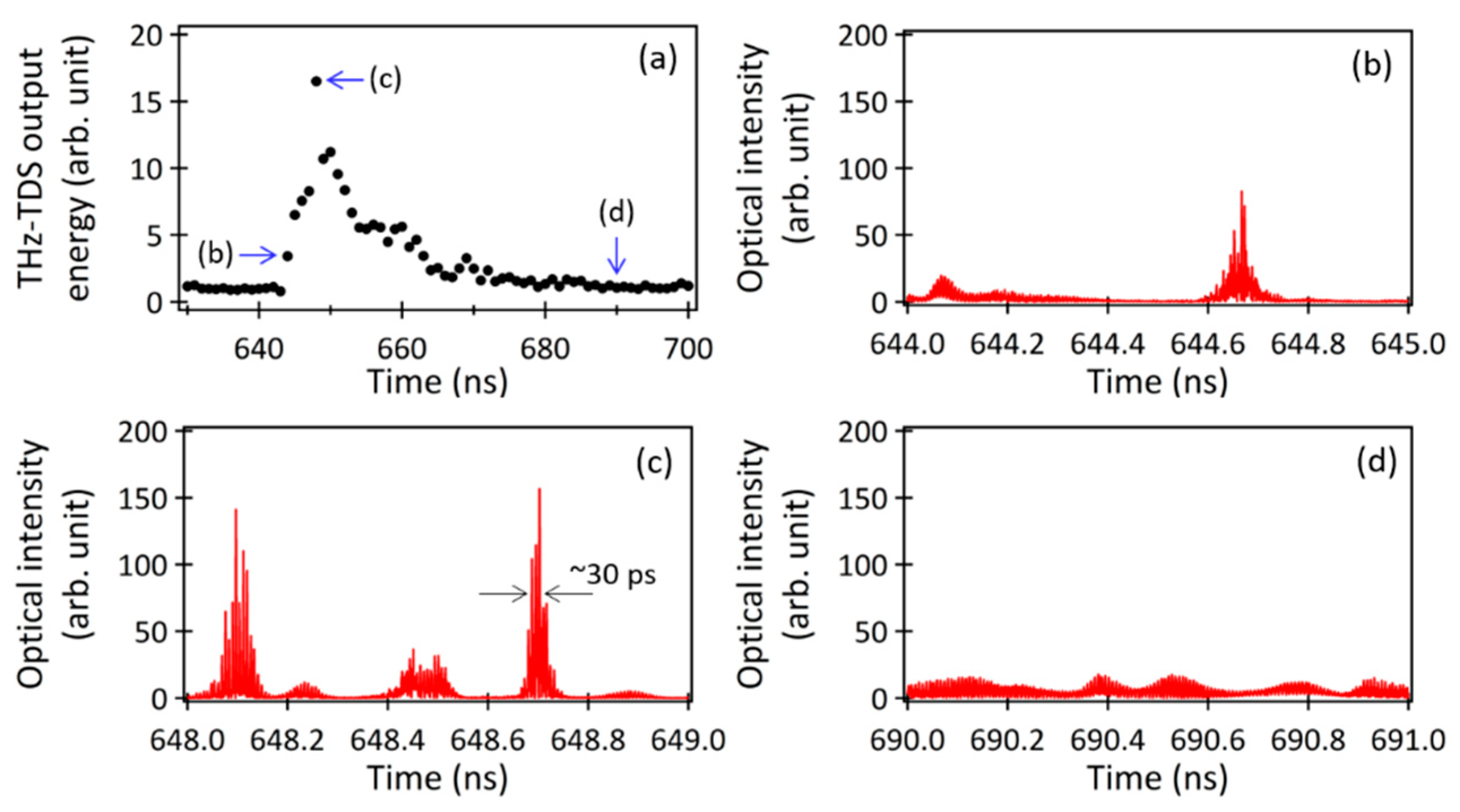

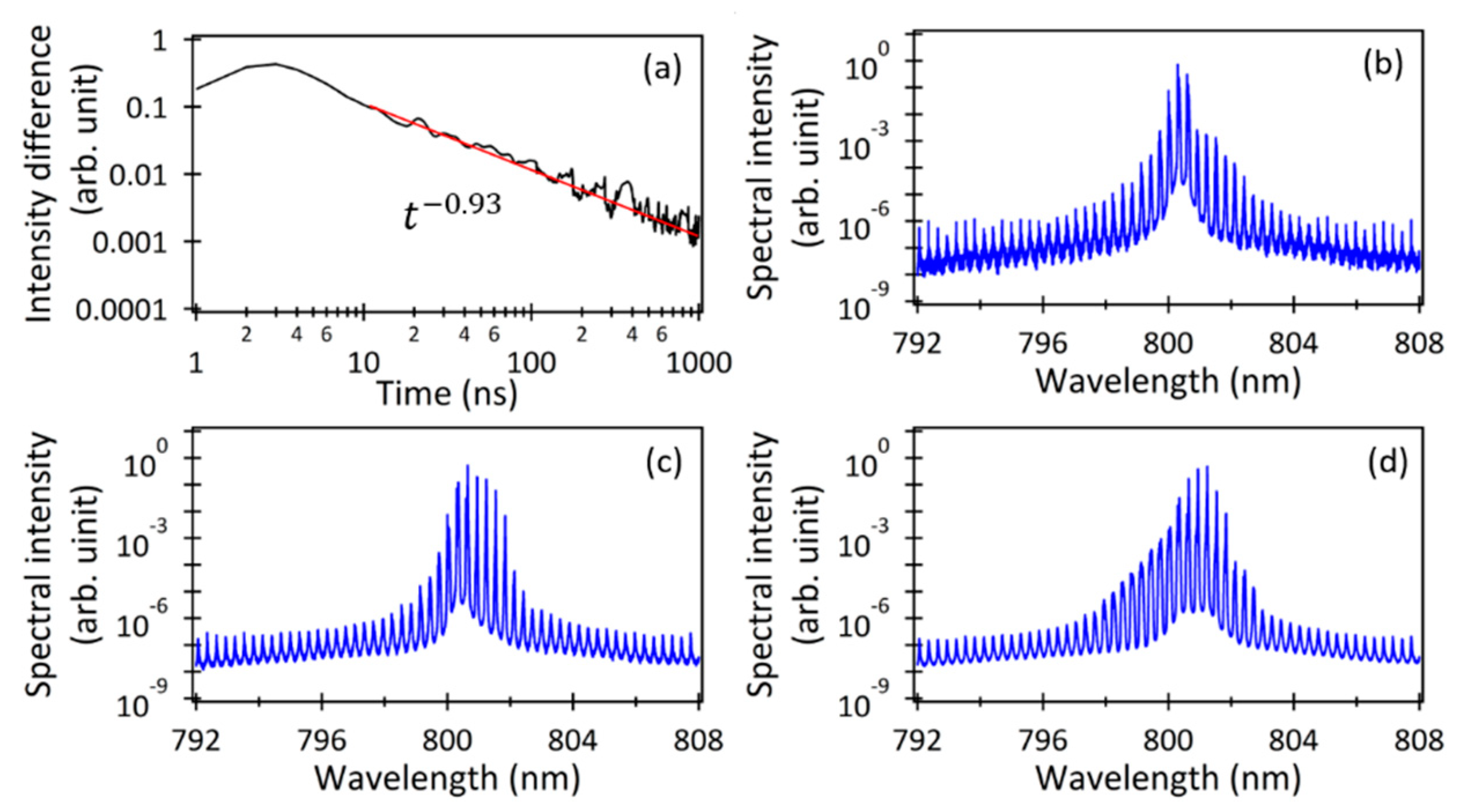

3.2. Characteristics of Intermittent Chaotic Oscillations

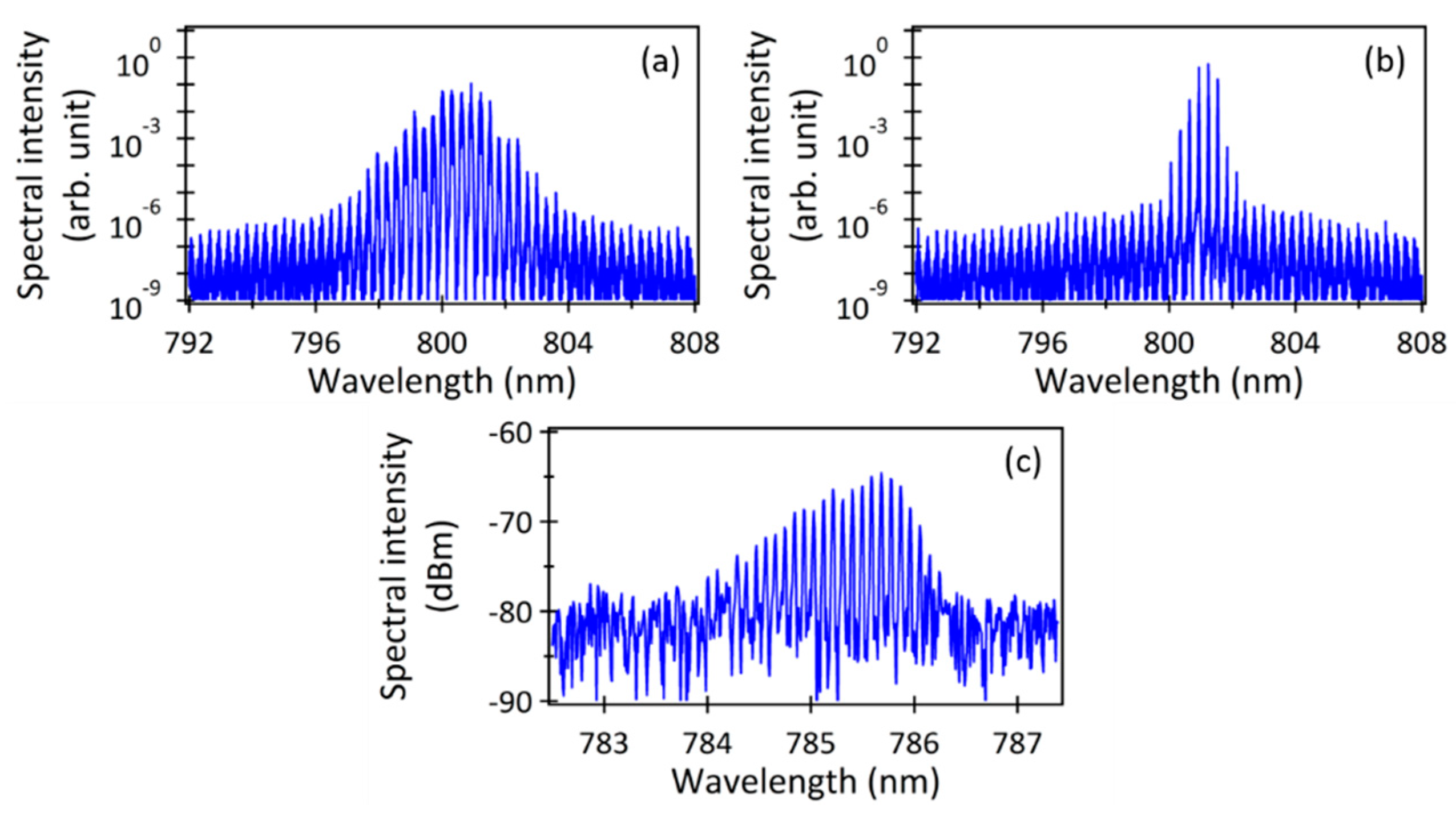

3.3. Time Convergence of Output Spectral Shapes

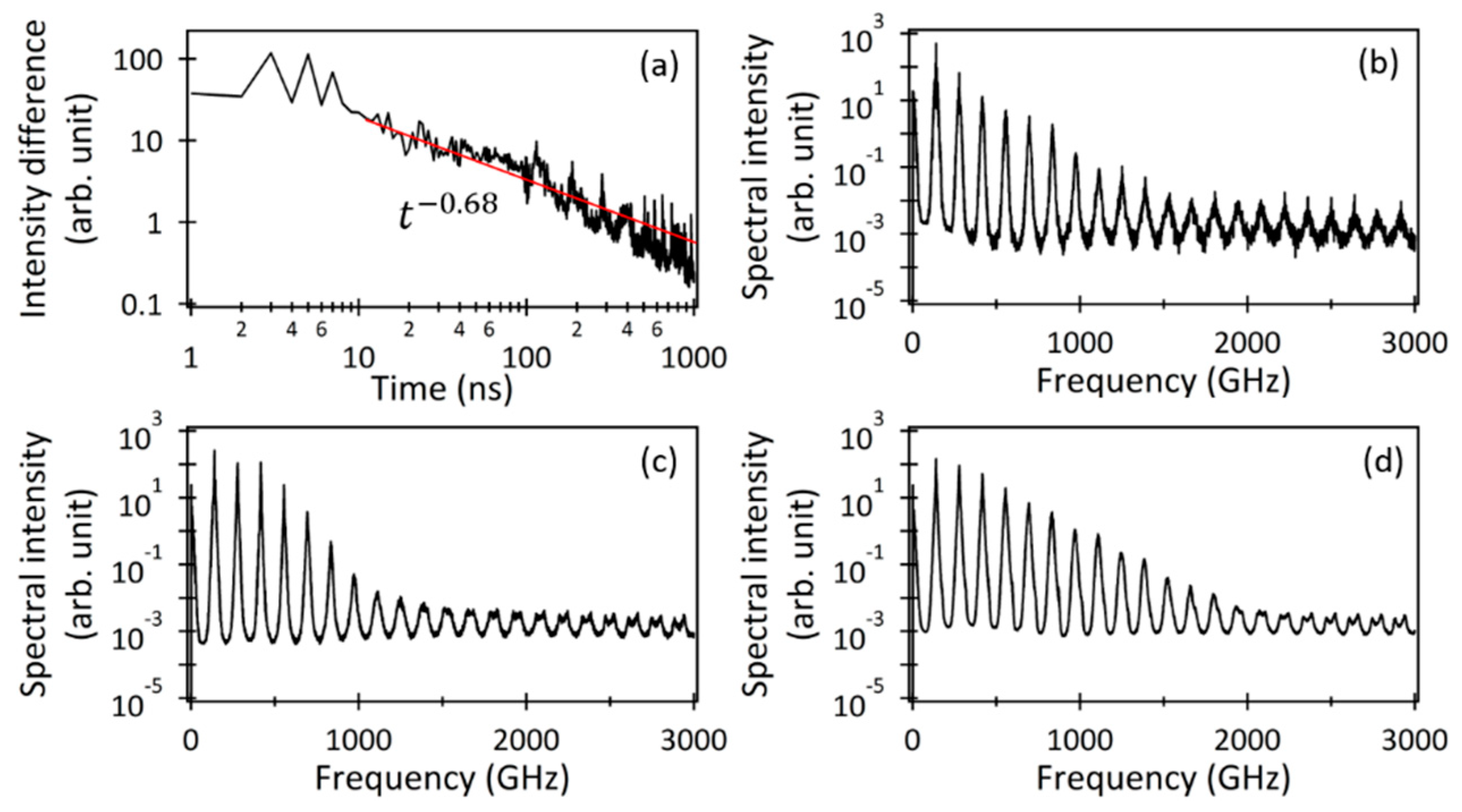

3.4. Expansion of Intermittent Chaotic Oscillation Region

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hangyo, M. Development and future prospects of terahertz technology. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 120101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundamentals of Terahertz Devices and Applications; Pavlidis, D., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; NJ, USA, 2021.

- Terahertz Optoelectronics; Sakai, K., Ed.; Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2005.

- Zhang, X.−C.; Xu, J. Introduction to THz Wave Photonics; Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2010.

- Auston, D.H.; Cheung, K. P.; Smith, P.R. Picosecond photoconducting Hertzian dipoles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1984, 45, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupeza, I.; Wilk, R.; Koch, M. Highly accurate optical material parameter determination with THz time-domain spectroscopy. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 4335–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withayachumnankul, W.; Fischer, B.M.; Lin, H.; Abbott, D. Uncertainty in terahertz time-domain spectroscopy measurement. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 2008, 25, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.R.; Chen, Z.C.; Lim, C.S.; Ng, B.; Hong, M.H. Broadband multi-layer terahertz metamaterials fabrication and characterization on flexible substrates. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 6990–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shutler, A.; Grischkowsky, D. Measurement of the transmission of the atmosphere from 0.2 to 2 THz. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 8830–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrekenhamer, D.; Rout, S.; Strikwerda, A.C.; Bingham, C.; Averitt, R.D.; Sonkusale, S.; Padilla, W.J. High speed terahertz modulation from metamaterials with embedded high electron mobility transistors. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 9968–9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, J.; Leonhardt, R.; Leon-Saval, S.G.; Argyros, A. THz propagation in kagome hollow-core microstructured fibers. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 18470–18478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, T.; Withayachumnankul, W.; Ung, B.S.-Y.; Menekse, H.; Bhaskaran, M.; Sriram, S.; Fumeaux, C. Experimental demonstration of reflectarray antennas at terahertz frequencies. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 2875–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, Md.S.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Franco, M.A.R.; Sultana, J.; Cruz, A.L.S.; Abbott, D. Terahertz optical fibers. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 16089–16117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Xu, D.; Jiang, B.; Ge, M.; Wu, L.; Yang, C.; Mu, N.; Wang, S.; Chang, C.; Chen, T.; Feng, H.; Yao, J. Terahertz spectroscopic diagnosis of early blast-induced traumatic brain injury in rats. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 4085–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, M.; Matsuura, S.; Sakai, K.; Hangyo, M. Multiple-frequency generation of sub-terahertz radiation by multimode LD excitation of photoconductive antenna. IEEE Microw. Guid. Wave Lett. 1997, 7 282−284.

- Morikawa, O.; Tonouchi, M.; Tani, M.; Sakai, K.; Hangyo, M. Sub-THz emission properties of photoconductive antennas excited with multimode laser diode. Jpn. J. Appl. Phy. 1999, 38, 1388–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, O.; Tonouchi, K.; Hangyo, M. Sub-THz spectroscopic system using a multimode laser diode and photoconductive antenna. Appl. Phy. Lett. 1999, 75, 3772–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, M.; Koch, M. Terahertz quasi time domain spectroscopy. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 17723–17733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, O.; Fujita, M.; Takano, K.; Hangyo, M. Sub-terahertz spectroscopic system using a continuous-wave broad-area laser diode and a spatial filter. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 063107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwashima, F.; Taniguchi, S.; Nonaka, K.; Hangyo, M.; Iwasawa, H. Stabilization of THz wave generation by using chaotic oscillation in a laser. Int. Conf. Infrared, Millimeter and Terahertz Waves, paper Tu-P.63, Rome, Italy, 5−10 September 2010.

- Kuwashima, F.; Shirao, T.; Kishibata, T.; Okuyama, T.; Akamine, Y.; Tani, M.; Kurihara, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Nagashima, T.; Hangyo, M. High efficient THz time domain spectroscopy systems using laser chaos and a metal V grooved waveguide. Int. Conf. Infrared, Millimeter and Terahertz Waves, paper W5-P24.2, Tucson, Arizona, USA, 14−18 September 2014.

- Kuwashima, F.; Jarrahi, M.; Cakmakyapan, S.; Morikawa, O.; Shirao, T.; Iwao, K.; Kurihara, K.; Kitahara, H.; Furuya, T.; Wada, K.; Nakajima, M.; Tani, M. Evaluation of high-stability optical beats in laser chaos by plasmonic photomixing. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 24833–24844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.; Yoshioka, H.; Jiaxun, Z.; Matsuyama, T.; Horinaka, H. Simple form of multimode laser diode rate equations incorporating the band filling effect. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 3019–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.; Matsuyama, T.; Horinaka, H. Simple gain form of 1.5μm multimode laser diode incorporating band filling and intrinsic gain saturation effects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phy. 2015, 54, 032101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Kitagawa, N.; Matsukura, S. , Matsuyama, T.; Horinaka, H. Timing and amplitude jitter in a gain-switched multimode semiconductor laser. Jpn. J. Appl. Phy. 2016, 55, 042702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Kitagawa, N.; Matsuyama, T. The degree of temporal synchronization of the pulse oscillations from a gain-switched multimode semiconductor laser. Materials 2017, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.; Kobayashi, K. External optical feedback effects on semiconductor injection laser properties. IEEE J. Quantum. Electron. 1980, 16, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegman, A.E. Lasers, University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 1004−1022.

- Ohtsubo, J. Chap. 5, Semiconductor Lasers−Stability, Instability and Chaos−, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Notation | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| m | Mode number | −30 ~ +30 | |

| τp | Photon lifetime | 2.0 | Ps |

| Trt | Round-trip time of the LD cavity | 7.1 | Ps |

| τfb | Delay time of the optical feedback fields | 1 | Ns |

| C1 | Nonradiative recombination rate | 2.0 × 108 | s−1 |

| C2 | Radiative recombination coefficient | 2.0 × 10−16 | m3 s−1 |

| C3 | Auger recombination coefficient | 0 | m6 s−1 |

| fc | Coupling coefficient of the optical feedback fields | 0 ~ 0.6 | |

| α | Linewidth enhancement factor | 3.0 | |

| β | Spontaneous emission factor | 1.0 × 10−6 | |

| εS | Gain compression factor | 0.05 × 10−23 | m3 |

| δf | Longitudinal mode spacing | 0.139 | THz |

| ∆τc | Coherence time of amplified spontaneous emission | 7.1 | Ps |

| e | Elementary electric charge | 1.60 × 10−19 | C |

| L | Laser cavity length | 300 | Μm |

| V | Laser cavity volume | 180 | μm3 |

| nr | Refractive index of the active layer | 3.6 | |

| ε0 | Dielectric constant for vacuum | 8.85 × 10−12 | F/m |

| h | Planck’s constant | 6.63 × 10−34 | Js |

| fm | Oscillation frequency of the mth-mode | 375 + 0.139m | THz |

| I | Bias current | r × Ith0 | mA |

| r | Pumping rate | 1.5 ~ 2.5 | |

| Ith0 | Threshold current for the central mode | 24 | mA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).