Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

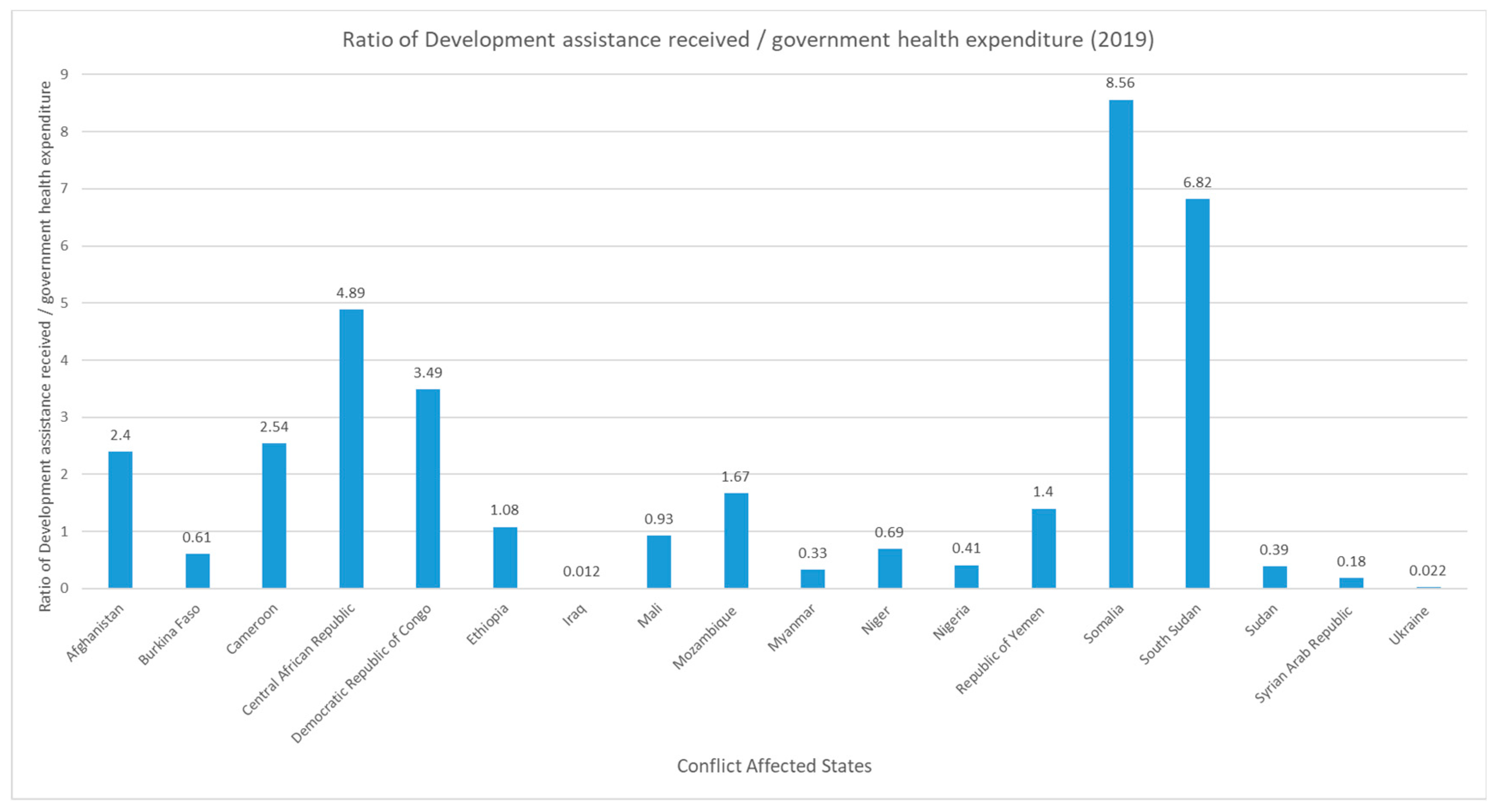

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

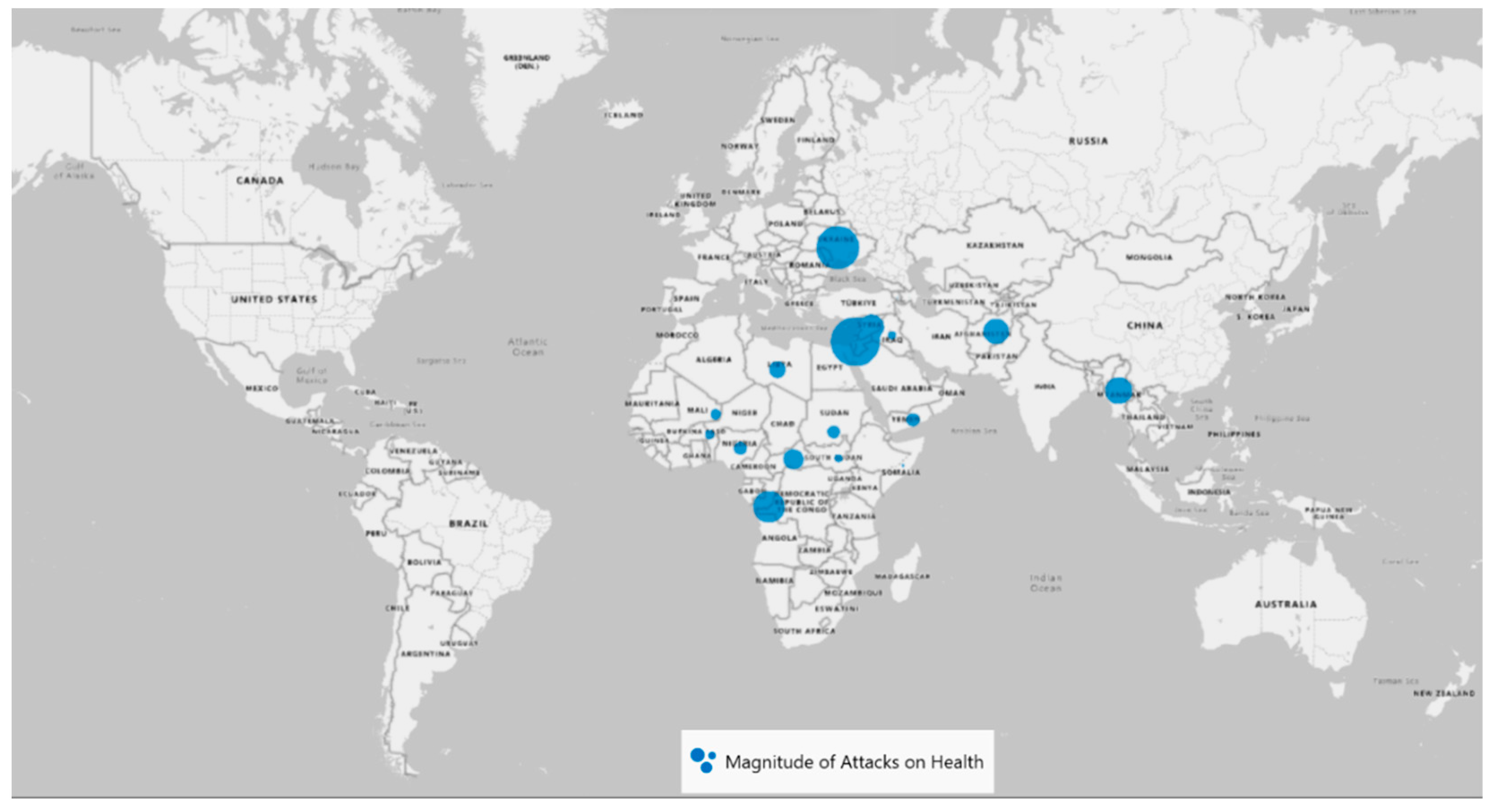

2. Attack on Health in Conflict Settings

3. International measures against attack on health

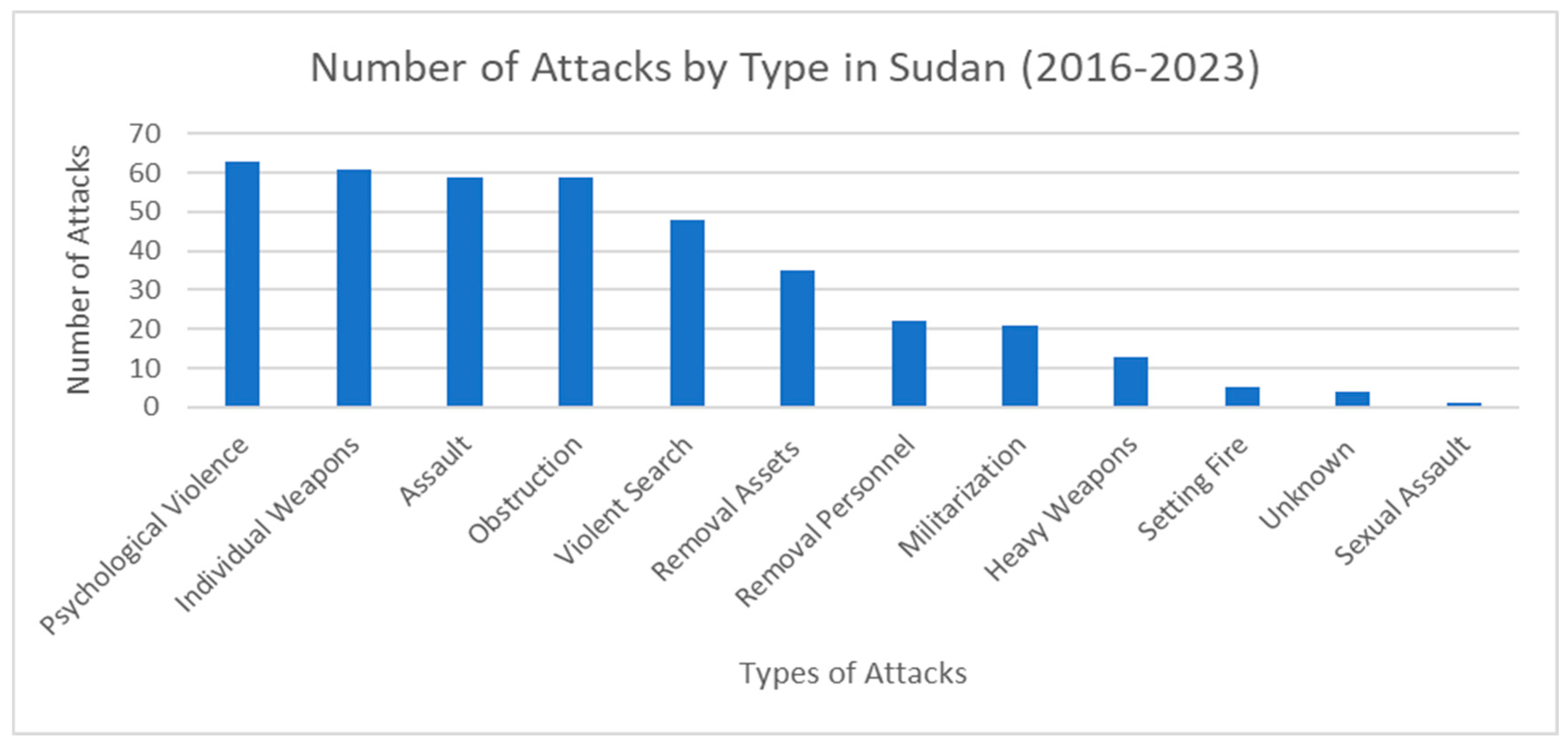

4. Healthcare in Threat – Sudan

5. Role of Health Diplomacy in Conflict Settings

6. Challenges for Health Diplomacy

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fidler, D.P. Health as Foreign Policy: Harnessing Globalization for Health. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21 (suppl_1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quality of Care in Fragile, Conflict-Affected and Vulnerable Settings: Taking Action; World Health Organization, Series Ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015203 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Devadas, S.; Elbadawi, I.; Norman, V. Loayza. Growth After War in Syria, 2019. Available online: https://erf.org.eg/publications/growth-after-war-in-syria/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business -- Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes : WHO’s Framework for Action. 2007, 44.

- International Committee of the Red Cross. Health Care in Danger: Making the Case; Publication; International Committee of the Red Cross: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/4072-health-care-danger-making-case (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- International Committee of the Red Cross. Respecting and protecting health care in armed conflicts and in situations not covered by international humanitarian law - Factsheet. International Committee of the Red Cross. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/respecting-and-protecting-health-care-armed-conflicts-and-situations-not-covered (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Faith Everett. Under threat: healthcare in conflict zones. The Health Policy Partnership. Available online: https://www.healthpolicypartnership.com/under-threat-healthcare-in-conflict-zones/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- IGNORING RED LINES Violence Against Health Care in Con_ict 2022; Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition and Insecurity Insight, 2022.

- WHO. Global Health Workforce Statistics Database. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/health-workforce (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- WHO. Hospital Beds (per 10 000 Population). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hospital-beds-(per-10-000-population) (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Brînzac, M.G.; Kuhlmann, E.; Dussault, G.; Ungureanu, M.I.; Cherecheș, R.M.; Baba, C.O. Defining Medical Deserts—an International Consensus-Building Exercise. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, ckad107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physicians for Human Rights. WAR CRIMES IN KOSOVO A Population-Based Assessment of Human Rights Violations Against Kosovar Albanians; Physicians for Human Rights: Boston, 1999; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Physicians For Human Rights. The Legacy of Oppression and Conflict on Health in Kosovo; June 16, 2009; US, 2009, pp. 22–34. Available online: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/perilous-medicine/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Taliban rue ambulance attack. The New Humanitarian. Available online: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2011/04/12/taliban-rue-ambulance-attack (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Fiona Terry. Violence against health care: insights from Afghanistan, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. International Review of the Red Cross. Available online: http://international-review.icrc.org/articles/violence-against-health-care-insights-afghanistan-somalia-and-democratic-republic-congo (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- MSF. MSF vaccination used as bait in unacceptable attack on civilians. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Available online: https://www.msf.org/msf-vaccination-used-bait-unacceptable-attack-civilians (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- MSF. After a week of intense fighting in Somalia, MSF is extremely concerned about the security of medical staff and safety of patients. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Available online: https://www.msf.org/after-week-intense-fighting-somalia-msf-extremely-concerned-about-security-medical-staff-and-safety (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Shell-Shocked: Civilians under Siege in Mogadishu - Somalia; 2007; pp 51–57. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/shell-shocked-civilians-under-siege-mogadishu (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- International Humanitarian Law Databases - Medical Units. International Committee of the Red Cross. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule28 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gci-1949/, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gci-1949/article-15 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Article 15 - Search for casualties. Evacuation. International Humanitarian Law Databases. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gci-1949/, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gci-1949/article-15 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/geneva-convention-relative-protection-civilian-persons-time-war (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol 1). The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-additional-geneva-conventions-12-august-1949-and (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Article 11 - Protection of medical units and transports. International Humanitarian Law Databases. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/apii-1977/, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/apii-1977/article-11 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Asi, Y.M.; Tanous, O.; Wispelwey, B.; AlKhaldi, M. Are There ‘Two Sides’ to Attacks on Healthcare? Evidence from Palestine. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 927–928 Available online:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrence McCoy. Why Hamas stores its weapons inside hospitals, mosques and schools. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/07/31/why-hamas-stores-its-weapons-inside-hospitals-mosques-and-schools/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- UNRWA. UNRWA condemns placement of rockets, for a second time, in one of its schools. United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Available online: https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/press-releases/unrwa-condemns-placement-rockets-second-time-one-its-schools (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Even wars have limits: Health-care workers and facilities must be protected. International Committee of the Red Cross. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/hcid-statement (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- United Nations. Security Council Adopts Resolution 2286 (2016), Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations. UN Press. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2016/sc12347.doc.htm (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- SSA Home. SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM FOR ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE (SSA). Available online: https://extranet.who.int/ssa/Index.aspx (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Hakki, L.; Stover, E.; Haar, R.J. Breaking the Silence: Advocacy and Accountability for Attacks on Hospitals in Armed Conflict. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2020, 102, 1201–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Failure of UN Security Council Resolution 2286 in Preventing Attacks on Healthcare in Syria. Syrian American Medical Society Foundation. Available online: https://www.sams-usa.net/reports/failure-un-security-council-resolution-2286-preventing-attacks-healthcare-syria/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Chattu, V.K.; Jean-Louis, G.; Zeller, J.L.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Aiding Universal Health Coverage through Humanitarian Outreach Services and Global Health Diplomacy in Resource-Poor Settings. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2021, 113, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar Al-Bashir: Sudan’s Ousted President. BBC News. December 5, 2011. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-16010445 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Salih, Z.M.; Beaumont, P.; Sudan’s Army Seizes Power in Coup and Detains Prime Minister. The Guardian. October 25, 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/25/sudan-coup-fears-amid-claims-military-have-arrested-senior-government-officials (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Sudan unrest: What are the Rapid Support Forces? | News | Al Jazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/16/sudan-unrest-what-is-the-rapid-support-forces (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Jake Horton; Kayleen Devlin. Sudan: Fighting between Rival Forces Hits Residential Areas. BBC News. April 17, 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65299756 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Samy Magdy. UN says Sudan conflict has displaced over 3 million people. PBS NewsHour. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/un-says-raging-conflict-in-sudan-has-displaced-over-3-million-people (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Reuters Staff. More than 3,000 People Killed, 6,000 Injured in Sudan Conflict - Health Minister. Reuters. June 17, 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/sudan-politics-casualties-idINC6N37W000 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Harriet Barber. Sudan hospitals and ambulances attacked during fighting between army and RSF. The Telegraph. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/sudan-fighting-khartoum-world-health-organisation-hospitals/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Emma Farge; Gabrielle Tétrault-Farber. “Almost impossible” to provide aid in Sudanese capital, IFRC says. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/ifrc-says-almost-impossible-provide-aid-around-sudanese-capital-2023-04-18/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Scott Gates; Håvard Mokleiv Nygård; Karim Bahgat. Patterns of Attacks on Medical Personnel and Facilities: SDG 3 meets SDG 16 – Peace Research Institute Oslo. The Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Available online: https://www.prio.org/publications/10785 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Reuters Staff. FACTBOX - Sudan’s President Omar Hassan al-Bashir. Reuters. July 14, 2008. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-warcrimes-sudan-bashir-profile-idUKL1435274220080714 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Lefkow, L. Darfur Destroyed. Hum. Rights Watch 2004.

- UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Available online: https://ucdp.uu.se/country/625 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Rule 25. Medical Personnel. Customary IHL Database. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule25 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Druce, P.; Bogatyreva, E.; Siem, F.F.; Gates, S.; Kaade, H.; Sundby, J.; Rostrup, M.; Andersen, C.; Rustad, S.C.A.; Tchie, A.; Mood, R.; Nygård, H.M.; Urdal, H.; Winkler, A.S. Approaches to Protect and Maintain Health Care Services in Armed Conflict – Meeting SDGs 3 and 16. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leebaw, B. The Politics of Impartial Activism: Humanitarianism and Human Rights. Perspect. Polit. 2007, 5, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siem, F.F. Leaving them behind: healthcare services in situations of armed conflict. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Laegeforening Tidsskr. Prakt. Med. Ny Raekke 2017, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Initiative. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/the-humanitarian-development-peace-initiative (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Abuelaish, I.; Goodstadt, M.S.; Mouhaffel, R. Interdependence between Health and Peace: A Call for a New Paradigm. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, O.J.; Davis, A.; Tucker, J.D.; Mason Meier, B. Chinese Global Health Diplomacy in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges. Glob. Health Gov. Sch. J. New Health Secur. Paradigm 2018, 12, 4–29. [Google Scholar]

- Feinsilver, J.M. Fifty Years of Cuba’s Medical Diplomacy: From Idealism to Pragmatism. Cuban Stud. 2010, 41, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiwa, A. The Latin American School of Medicine (Elam): Admissions, Academics and Attitudes. Int. J. Cuban Stud. 2017, 9, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldbaum, H.; Lee, K.; Michaud, J. Global Health and Foreign Policy. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Médecins Sans Frontières. About us: What is MSF? What we do? Our history. Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF)/Doctors Without Borders. Available online: https://msfsouthasia.org/our-history/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- International Committee of the Red Cross. History of the ICRC. ICRC. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/history-icrc (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- International Committee of the Red Cross. Partnership is key to ending violence against health care. ICRC. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/partnership-key-ending-violence-against-health-care (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Safeguarding Health in Conflict. About the Coalition. Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition. Available online: https://www.safeguardinghealth.org/about-coalition (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Attacks on Health Care Initiative. What is the Atacks on Health Care Initiative. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/attacks-on-health-care-initiative (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- WHO. Global Health and Peace Initiative (GHPI) - Fifth Draft of the Roadmap; World Health Organization (WHO). 2023, pp. 2–4. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-health-and-peace-initiative (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- WHO EMRO. Somalia implements ground-breaking project aimed at improving psychosocial support and mental health care for young people affected by conflict through a socially-inclusive integrated approach for peace-building. World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/somalia/news/somalia-implements-ground-breaking-project-aimed-at-improving-psychosocial-support-and-mental-health-care-for-young-people-affected-by-conflict-through-a-socially-inclusive-integrated-app.html (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Coninx, R.; Ousman, K.; Mathilde, B.; Kim, H.-T. How Health Can Make a Contribution to Peace in Africa: WHO’s Global Health for Peace Initiative (GHPI). BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7 (Suppl 8), e009342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, F.M. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War: Transnational Midwife of World Peace. Med. War 1990, 6, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Statement of the Nobel Committee Upon Awarding the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize to IPPNW. International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Available online: https://www.ippnw.org/1985/12/10/1985-nobel-peace-prize/' (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Development Assistance for Health Database 1990-2020, 2021. [CrossRef]

- WHO EMRO. Global health security is integral to foreign policy. World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/health-diplomacy/foreign-policy.html (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- WHO EMRO. Global health needs global health diplomacy. World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/health-diplomacy/about-health-diplomacy.html (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- WHO EMRO. Health challenges. World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/health-diplomacy/health-challenges.html (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Tom Daschle; Bill Frist. The Case for Strategic Health Diplomacy: A Study of PEPFAR.; Bipartisan Policy Center, 2015, pp. 10–12. Available online: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/the-case-for-strategic-health-diplomacy-a-study-of-pepfar/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- PEPFAR Organization and Implementation. In Evaluation of PEPFAR.; National Academies Press (US), 2013.

- Lyman, P.N.; Wittels, S.B. No Good Deed Goes Unpunished: The Unintended Consequences of Washington’s HIV/AIDS Programs. Foreign Aff. 2010, 89, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, M.A.; Weiss, H.A.; Hayes, R.J. Male Circumcision as a Measure to Control HIV Infection and Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 14, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, B.E.; Landis, S.T. The Stabilizing Effects of International Politics on Bilateral Trade Flows. Foreign Policy Anal. 2015, 11, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, K.; Nam, S.L.; Ramalingam, B.; Pozo-Martin, F. Governance and Capacity to Manage Resilience of Health Systems: Towards a New Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassmin Moor. Cash and vouchers can improve health outcomes – but you must understand the challenges first. The CALP Network. Available online: https://www.calpnetwork.org/blog/cva-can-improve-health-outcomes/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Goodman, C.; Opwora, A.; Kabare, M.; Molyneux, S. Health Facility Committees and Facility Management - Exploring the Nature and Depth of Their Roles in Coast Province, Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.; Al-Dahir, S.; Al Mulla, T.; Lami, F.; Hossain, S.M.M.; Baqui, A.; Burnham, G. Resilience of Health Systems in Conflict Affected Governorates of Iraq, 2014–2018. Confl. Health 2021, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, A.; Day, G.; Gupta, S.; Ventriglio, A.; Ruiz, R.; Chumakov, E.; Desai, G.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.; Torales, J.; Juan Tolentino, E.; Bhui, K.; Bhugra, D. Geopolitical Factors and Mental Health I. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persaud, A.; Bhat, P.S.; Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. Geopolitical Determinants of Health. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2018, 27, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, S.; Ramadani, L.; Boeckmann, M. Health Equity in Climate Change and Health Policies: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; Lawless, A.; Delany, T.; Macdougall, C.; Williams, C.; Broderick, D.; Wildgoose, D.; Harris, E.; Mcdermott, D.; Kickbusch, I.; Popay, J.; Marmot, M. Evaluation of Health in All Policies: Concept, Theory and Application. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29 (suppl 1), i130–i142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.; Ashton, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Clemens, T.; Douglas, M. ‘Health in All Policies’—A Key Driver for Health and Well-Being in a Post-COVID-19 Pandemic World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, Y. International Health Cooperation in the Post-Pandemic Era: Possibilities for and Limitations of Middle Powers in International Cooperation. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, S.; Tafuro Ambrosetti, E. Making the Best Out of a Crisis: Russia’s Health Diplomacy during COVID-19. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yang, S. Political Economy of Vaccine Diplomacy: Explaining Varying Strategies of China, India, and Russia’s COVID-19 Vaccine Diplomacy. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2023, 30, 865–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K.; Dhama, K. India’s Role in COVID-19 Vaccine Diplomacy. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.L.; Falkenbach, M.; Siciliani, L.; McKee, M.; Wismar, M.; Figueras, J. From Health in All Policies to Health for All Policies. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e718–e720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattu, V.K.; Knight, W.A. Global Health Diplomacy as a Tool of Peace. Peace Rev. 2019, 31, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbende, L.; Helldén, D.; Mbunga, B.; Schedwin, M.; Kazenza, B.; Viberg, N.; Wanyenze, R.; Ali, M.M.; Alfvén, T. Interactions between Health and the Sustainable Development Goals: The Case of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António Guterres. International Laws Protecting Civilians in Armed Conflict Not Being Upheld, Secretary-General Warns Security Council, Urging Deadly Cycle Be Broken. UN Press. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15292.doc.htm (accessed on 18 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).