Submitted:

25 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

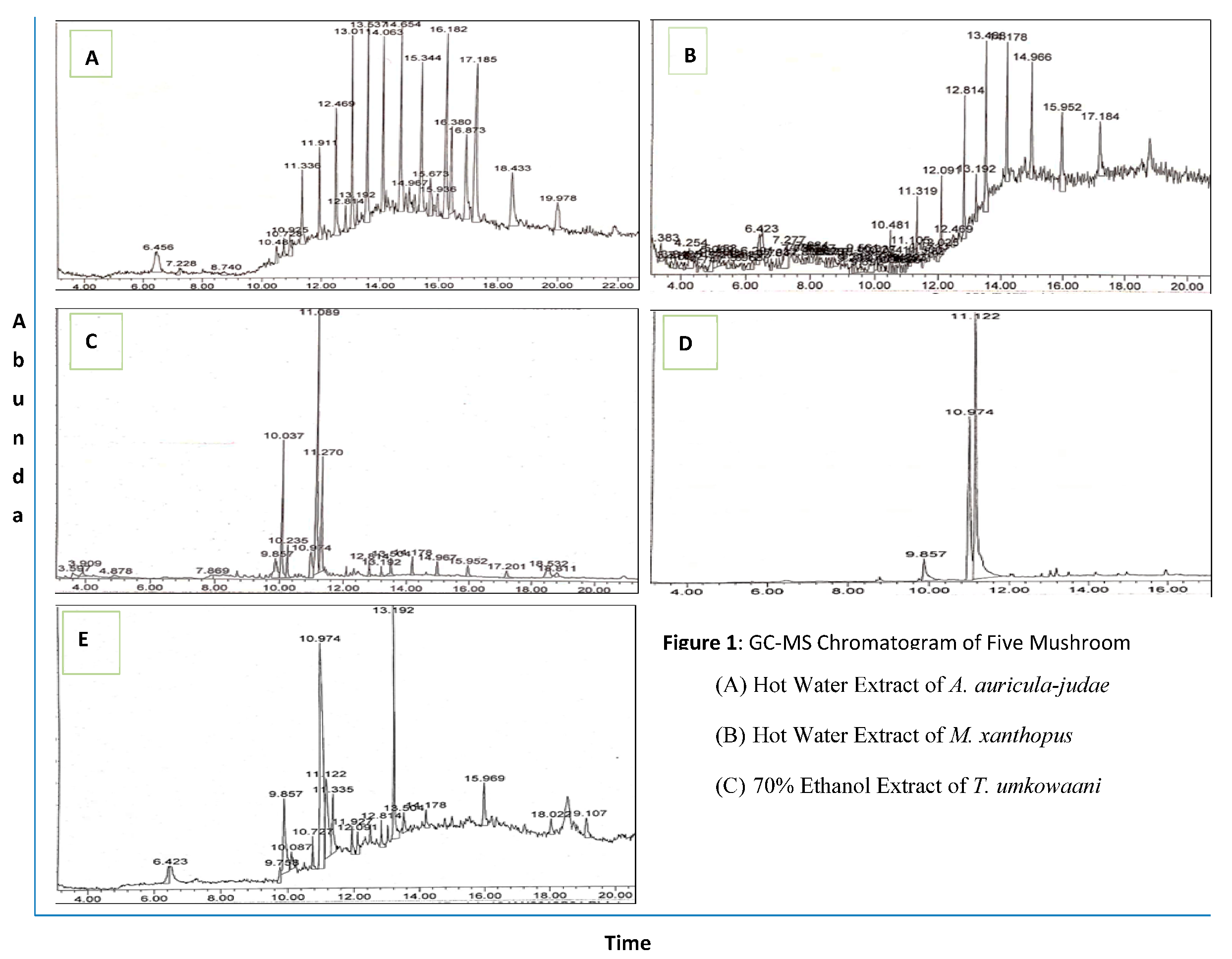

2.1. GC-MS Analysis of Wild Mushroom Extracts

2.1.1. GC-MS Analysis of Auricularia auricula-judae

| Peaks | RT (min) | PA (%) | IUPAC Name and MF of Compounds | Nature of Compounds | Pharmacological and Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19.98 | 10.65 | Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9,11,11,13,13,15,15-hexadecamethyl- (C16H50O7Si8) | Siloxane | Antidepressant, antimicrobial | [41,69] |

| 2 | 18.43 | 7.12 | Silicic acid, diethyl bis(trimethylsilyl) ester (C10H28O4Si3) | Ester | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antimalarial, anti-inflammatory | [70,71] |

| 3 | 17.19 | 4.43 | Di-n-octyl phthalate (C24H38O4) | Phthalic acid | Antimicrobial, insecticidal | [72,73] |

| 4 | 16.87 | 6.12 | Di-n-decylsulfone (C20H42O2S) | Phthalate | Antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-helminthic, antagonistic, larvicidal | [74,75] |

| 5 | 16.38 | 7.98 | 2-Methyl-6-methylene-octa-1,7-dien-3-ol (C10H16O) | acyclic monoterpenoids | No activity reported | |

| 6 | 16.18 | 5.65 | 1-Heptanol, 2,4-dimethyl- (R, R)- (+)- (C9H20O) | Alcohol | Antifungal, antioxidant, anticholinesterase | [76,77,78] |

| 7 | 15.34 | 4.31 | Cyclohexano, 2,4-dimethyl- (C8H16O) | Cyclohexane | Anticancer | [79] |

| 8 | 14.65 | 3.43 | Carbonic acid, methyl octyl ester (C10H20O3) | Ester | Hepatoprotective, antihypertensive, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, cholesterol-lowering, anti-urolithiasis, antifertility | [80] |

| 9 | 14.06 | 5.25 | 1-Allylcyclopropyl) methanol (C7H12O) | Cycloalkane methanol | No activity reported | |

| 10 | 13.64 | 7.23 | 2-Methyl-1-ethylpyrrolidine (C7H15N) | Pyrrolidines | Anti-tumor | [81] |

| 11 | 13.01 | 6.33 | Oxirane, 2,2’-(1,4-dibutanediyl) bis- (C8H14O2) | Epoxides | Antibacterial | [82] |

| 12 | 12.47 | 11.34 | 2-Nonanol, 5-ethyl- (C11H24O) | Fatty alcohol | Anticancer | [83] |

| 13 | 11.91 | 5.86 | 1-Hexene, 4, 5-dimethyl- (C8H16) | Alkene | Antimicrobial | [84] |

| 14 | 11.34 | 14.21 | Phenol, 2,6-bis (1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl-, methyl carbamate (C17H27NO2) | Alkyl benzene | Antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, temporarily treat pharyngitis | [85,86] |

2.1.2. GC-MS Analysis of Hot Water Extract of Microporus xanthopus

| Peaks | RT (min) | PA (%) | IUPAC Name and MF of Compounds | Nature of Compounds | Pharmacological and Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.42 | 8.11 | 1-Heptanol, 2,4-dimethyl-, (2S, 4R) -(-)- (C9H20O) | Alcohol | Antifungal | [76,77] |

| 2 | 7.28 | 4.34 | Oxirane, 2,2’-(1,4-butanediyl) bias- (C8H14O2) | Epoxides | No activity reported | |

| 3 | 10.48 | 3.67 | 3-Methyl-2-(2-oxopropyl) furan (C8H10O2) | Aldehyde | Antioxidant, antimicrobial | [103,104] |

| 4 | 11.32 | 5.50 | 7-Hexadecenal, (Z)- (C16H30O) | Fatty aldehyde | Antiviral, antibacterial | [105,106] |

| 5 | 12.09 | 7.87 | 1,2,3,3a-Tetrahydro-7-methyl-10-4-methylphenyl) benzo [c] cyclopenta [f] -1,2-diazepine (C20H20N2) | Aromatic organic heterocyclic | No activity reported | |

| 6 | 12.81 | 4.41 | Tetradecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl- (C17H36) | Isoprenoid lipid | Antifungal, antibacterial, and nematicidal | [107] |

| 7 | 13.19 | 4.19 | Heptacosane (C27H56) | N-Alkanes | Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, antimalarial, antidermatophytic | [108,109] |

| 8 | 13.47 | 11.39 | Didodecyl phthalate (C32H54O4) | Phthalate | Vasodilator, antihypertensive, uric acid excretion stimulant and diuretic, antimicrobial, antifouling | [110,111] |

| 9 | 14.18 | 1.17 | Acetamide, N-[3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo [a, d] cyclohepten-5-ylidene)propyl] -2,2,2-triflouro-N-methyl (C21H20F3NO) | Unknown | Reducing depressive symptoms |

[112] |

| 10 | 14.97 | 13.76 | 2,2’-Divinylbenzophenone (C17H14O) | Unknown | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant | [113] |

| 11 | 15.95 | 14.18 | Trans-1, 1’-Bibenzoindanylidene (C18H16) | Unknown | No activity reported | |

| 12 | 17.18 | 16.32 | 1-Monolinoleoylglycerol trimethylsilyl ether (C27H54O4Si2) | Steroid | Anti-diuretic, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, antimicrobial antioxidant, anti-arthritic, antiasthma | [114,115] |

2.1.3. GC-MS Analysis of 70% ethanol extract of Termitomyces umkowaani

| Peaks | RT (min) | PA (%) | IUPAC Name and MF of Compounds | Nature of Compounds | Pharmacological and Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.88 | 5.68 | Butanedioic acid diethyl ester (C8H14O4) | Fatty acid | Antimicrobial, antispasmodic, and anti-inflammatory | [135] |

| 2 | 7.87 | 4.11 | Octadecanoic acid, ethyl ester (C20H40O2) | Fatty acid esters | Hypocholesterolemic 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, lubricant, and antimicrobial | [11,136] |

| 3 | 9.86 | 2.45 | h-Hexadecanoic acid (C16H32O2) | Fatty acid (aka palmitic acid) | Antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic, nematicide, pesticide, antiandrogenic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, immunostimulant, hemolytic 5-α reductase inhibitor, lipooxygenase inhibitor | [3,137] |

| 4 | 10.04 | 7.90 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester (C18H36O2) | Fatty acid ester (aka palmitic acid ester) | Antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic, nematicide, pesticide, anti-androgenic, hemolytic 5-α reductase inhibitor | [3] |

| 5 | 10.24 | 8.78 | i-Propyl hexadecanoate (C19H38O2) | Fatty acid | No activity reported | |

| 6 | 10.97 | 9.98 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z, Z)- (C18H32O2) |

Fatty acid (aka conjugated linoleic acid) | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic, antimicrobial, antitumor, insecticide, antiarthritic, antieczemic hepatoprotective, antiandrogenic, nematicide, antihistaminic, antiacne, hemolytic 5-α reductase inhibitor, anti-coronary | [3,80,137,138,139] |

| 7 | 11.09 | 13.43 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, ethyl ester (C20H36O2) | Fatty acid ester (aka omega-6) | Hypocholesterolemic, nematicide, antiacne, antiarthritic, hepatoprotective, antimicrobial, antiandrogenic, hemolytic 5-α reductase inhibitor, antihistaminic, anti-coronary, insecticide, antieczemic | [3,70,80] |

| 8 | 11.27 | 0.89 | Isopropyl linoleate (C21H38O2) | β-carotene | Antimicrobial, antioxidant | [22,43,140,141] |

| 9 | 13.19 | 1.50 | 1-Monolinoleoylglycerol trimethylsilyl ether (C27H54O4Si2) | Steroid | Antimicrobial, antiasthma, anti-diuretic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic | [114] |

| 10 | 14.18 | 15.90 | 12-Methyl-E, E-2, 13-Octadecadien-1-ol (C19H36O) | Alcohol | Antimicrobial | [142] |

| 11 | 14.97 | 1.12 | 7-Hexadecenal, (Z)- (C16H30O) | Fatty aldehyde | Antiviral, antibacterial | [105,106] |

| 12 | 15.95 | 3.60 | 1, 2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisooctyl ester (C24H38O4) | Ester | Antimicrobial, antifouling | [143] |

| 13 | 17.20 | 18.90 | Tetracosamethyl-cyclododeca siloxane (C24H72O12Si12) | Siloxane | No activity reported | |

| 14 | 18.53 | 5.76 | Heptasiloxane hexadecamethyl (C16H48O6Si7) | Organosiloxane | No activity reported |

2.1.4. GC-MS Analysis of chloroform extract of Trametes elegans

| Peaks | RT (min) | PA (%) | IUPAC Name and MF of Compounds | Nature of compounds | Pharmacological and Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.86 | 16.89 | n-Hexadecanoic acid (C16H32O2) | Fatty Acid | Antioxidant, antiandrogenic, hypocholesterolemic, nematicide, pesticide, antibiofilm formation | [137,159] |

| 2 | 10.97 | 72.90 | Oleic acid (C18H34O2) | Fatty Acid | Antioxidant, apoptotic activity in tumor cells, anticancer, antibiofilm formation | [159,160] |

| 3 | 11.12 | 10.21 | Octadecanoic acid (C18H36O2) | Fatty Acid | Antimicrobial, antibiofilm formation | [161,159] |

2.1.5. GC-MS Analysis of hot water extract of Trametes versicolor

| Peaks | RT (min) | PA (%) | IUPAC Name and MF of Compounds | Nature of compounds | Pharmacological and Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.42 | 26.56 | Phenol, 2,6-bis (1,1-dimethyl ethyl)-4- methyl, methylcarbamate (C17H27NO2) | Phenol | Antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, oral anesthetic/analgesic, temporarily treat pharyngitis | [85,86] |

| 2 | 9.86 | 2.20 | n-Hexadecanoic acid (C16H32O2) | Palmitic acid | Antioxidant, nematicide, pesticide, hypocholesterolemic, antiandrogenic | [165] |

| 3 | 10.73 | 3.40 | Nonadecane (C19H40) | Hydrocarbon | No activity reported | |

| 4 | 11.12 | 8.41 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic (Z, Z)- (C18H32O2) |

Polyunsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory, hypocholesterolemic, antitumor, hepatoprotective, nematicide, insecticide, antibiofilm formation, antihistaminic, antieczemic, antiacne, hemolytic 5-α reductase inhibitor, antiandrogenic, antiarthritic, anti-coronary, antimicrobial | [114,159,166,167,168] |

| 5 | 11.34 | 5.73 | 7-Hexadecenal, (Z)- (C16H30O) | Fatty aldehyde | Antiviral, antibacterial | [105,106] |

| 6 | 13.19 | 12.20 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2-[(trimethylsilyl) oxy]-1-[[(trimethylsilyl) oxy] methyl] ethyl ester (Z, Z, Z)- (C27H52O4Si2) | polyunsaturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial, antioxidant |

[169,170] |

| 7 | 15.97 | 22.40 | 1-Momolinoleoylglycerol trimethylsilyl ether (C27H54O4Si2) | Antimicrobial, antiasthma, anti-diuretic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic | [114] | |

| 8 | 18.11 | 19.10 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisooctyl ester (C24H38O4) | Benzoic acid ester | Biopesticides, antibacterial | [171,172] |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Wild Mushrooms Collection and Identification

3.2. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds

3.3. GC-MS Analysis of Extracts

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations/Acronyms

| AAJ | Auricularia auricula-judae |

| CE | Chloroform extract |

| EE | 70% ethanol extract |

| FAs | Fatty acids |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry |

| HWE | Hot water extract |

| LA | Linolenic acid |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MF | Molecular formula |

| MX | Microporus xanthopus |

| PA | Peak area |

| PLA | Palmitic acid |

| RT | Retention time |

| TRE | Trametes elegans |

| TRV | Trametes versicolor |

| TU | Termitomyces umkowaani |

References

- El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Eid, Y.; Prokisch, J. Edible Mushrooms for Sustainable and Healthy Human Food: Nutritional and Medicinal Attributes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulay, R.M.R.; Batangan, J.N.; Kalaw, S.P.; De Leon, A.M.; Cabrera, E.C.; Kimura, K.; Eguchi, F.; Reyes, R.G. Records of Wild Mushrooms in the Philippines: A Review. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye-isijola, M.O.; Olajuyigbe, O.O.; Gbolagade, S.G.; Coopoosamy, R.M. Bioactive Compounds in Ethanol Extract of Lentinus Squarrosulus Mont - A Nigerian Medicinal Macrofungus. African J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Saccomanno, B.; de Wit, P.J.G.M.; Collemare, J. Regulation of Secondary Metabolite Production in the Fungal Tomato Pathogen Cladosporium Fulvum. FUNGAL Genet. Biol. 2015, 84, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturella, G.; Ferraro, V.; Cirlincione, F.; Gargano, M.L. Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Compounds, Use, and Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübeck, M.; Lübeck, P.S. Fungal Cell Factories for Efficient and Sustainable Production of Proteins and Peptides. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, B.; Çöleri Cihan, A.; Akata, I.; Altuner, E.M. Anti-Biofilm and Antimicrobial Activities of Five Edible and Medicinal Macrofungi Samples on Some Biofilm Producing Multi Drug Resistant Enterococcus Strains. Turkish J. Agric. - Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.J.; Ferreira, R.I.C.F.; Lourenço, I.; Costa, E.; Martins, A.; Pintado, M. Wild Mushroom Extracts as Inhibitors of Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Pathogens 2014, 3, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah-agyei, G.O.; Ayeni, K.I. GC-MS Analysis of Bioactive Compounds and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of the Extracts of Daedalea Elegans: A Nigerian Mushroom. African J. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 14, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Tripathy, A. Isolation and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Irpex Lacteus Wild Fleshy Fungi. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 7, 424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, V.; Tomar, S.; Yadav, P.; Vishwakarma, S.; Singh, M.P. Elemental Analysis, Phytochemical Screening and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity of Pleurotus Ostreatus through In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila Giraldo, L.R.; Pérez Jaramillo, C.C.; Méndez Arteaga, J.J.; Murillo-Arango, W. Nutritional Value and Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Wild Macrofungi. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, E.; Slusarczyk, J.; Czerwik-marcinkowska, J. Fungi and Algae as Sources of Medicinal and Other Biologically Active Compounds : A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, O.E.; Oyetayo, V.O.; Awala, S.I. Evaluation of the Mycochemical Composition and Antimicrobial Potency of Wild Macrofungus, Rigidoporus Microporus ( Sw ). J. Phytopharm. 2017, 6, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, M.; Gurung, A.B.; Bhattacharjee, A. Analysis of the Bioactive Metabolites of the Endangered Mexican Lost Fungi Campanophyllum – A Report from India Analysis of the Bioactive Metabolites of the Endangered Mexican Lost. Mycobiology 2020, 48, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasser, S. Medicinal Mushroom Science: Current Perspectives, Advances, Evidences, and Challenges. Biomed. J. 2014, 37, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetayo, V.O.; Akingbesote, E.T. Microbial Biosystems Assessment of the Antistaphylococcal Properties and Bioactive Compounds of Raw and Fermented Trametes Polyzona ( Pers.) Justo Extracts. Microb. Biosyst. 2022, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assemie, A. The Effect of Edible Mushroom on Health and Their Biochemistry. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Insights into Health-Promoting Effects of Jew’s Ear (Auricularia Auricula-Judae). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, R.; Min, H.; Zhang, S.; Hu, S. Formation Optimization, Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Auricularia Auricula-Judae Polysaccharide Nanoparticles Obtained via Antisolvent Precipitation. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, T.; Yao, F.; Kang, W.; Lu, L.; Xu, B. A Systematic Study on Mycochemical Profiles, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of 30 Varieties of Jew’s Ear (Auricularia Auricula-Judae). Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herawati, E.; Ramadhan, R.; Ariyani, F.; Marjenah; Kusuma, I.W.; Suwinarti, W.; Mardji, D.; Amirta, R.; Arung, E.T. Phytochemical Screening and Antioxidant Activity of Wild Mushrooms Growing in Tropical Regions. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 4716–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, K.N.; Patil, V.P. Qualitative Analysis of Bioactive Components in Microporus Xanthopus ( Fr.) Kuntze. Biol. Forum – An Int. J. 2023, 15, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Paloi, S.; Kumla, J.; Paloi, B.P.; Srinuanpan, S.; Hoijang, S.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Acharya, K.; Suwannarach, N.; Lumyong, S. Termite Mushrooms (Termitomyces), a Potential Source of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds Exhibiting Human Health Benefits: A Review. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rava, M.; Ali, R.; Das, S. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Study of Termitomyces Entolomoides in Western Assam. Int. J. Sci. Res. Biol. Sci. 2019, 6, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibuhwa, D.D. Termitomyces Species from Tanzania, Their Cultural Properties and Unequalled Basidiospores. J. Biol. Life Sci. 2012, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiya Seelan, J.S.; Shu Yee, C.; She Fui, F.; Dawood, M.; Tan, Y.S.; Kim, M.J.; Park, M.S.; Lim, Y.W. New Species of Termitomyces (Lyophyllaceae, Basidiomycota) from Sabah (Northern Borneo), Malaysia. Mycobiology 2020, 48, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karun, N.C.; Sridhar, K.R. Occurrence and Distribution of Termitomyces (Basidiomycota, Agaricales ) in the Western Ghats and on the West Coast of India. Czech Mycol. 2013, 65, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olou, B.A.; Krah, F.S.; Piepenbring, M.; Yorou, N.S.; Langer, E. Diversity of Trametes (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) in Tropical Benin and Description of New Species Trametes Parvispora. MycoKeys 2020, 65, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, A.; Chawla, P. In Vitro Bioactivity, Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy of Modified Solvent Evaporation Assisted Trametes Versicolor Extract. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awala, S.I.; Oyetayo, V.O. The Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of the Extracts Obtained from Trametes Elegans Collected from Osengere in Ibadan, Nigeria. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 8, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakasundar, A.; Mazlan, N.B.; Ishak, R.B. Trametes Elegans: Sources and Potential Medicinal and Food Applications. Malaysian J. Med. Heal. Sci. 2023, 19, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, T.; Pawlikowska, M.; Sobocińska, J.; Wrotek, S. COVID-19 and Cancer Diseases—The Potential of Coriolus Versicolor Mushroom to Combat Global Health Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L. Research Progress on the Extraction, Structure, and Bioactivities of Polysaccharides from Coriolus Versicolor. Foods 2022, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, M. Antioxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Activities and Chemical Composition of Extracts from the Mushroom Trametes Versicolor. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013, 2, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Trametes Versicolor (Synn. Coriolus Versicolor) Polysaccharides in Cancer Therapy: Targets and Efficacy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.H.K.; Or, P.M.Y. Polysaccharide Peptides from Coriolus Versicolor Competitively Inhibit Model Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Probe Substrates Metabolism in Human Liver Microsomes. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristy, A.T.; Islam, T.; Ahmed, R.; Hossain, J.; Reza, H.M.; Jain, P. Evaluation of Total Phenolic Content, HPLC Analysis, and Antioxidant Potential of Three Local Varieties of Mushroom: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhaji, L.; Mijatović, S.; Maksimović-Ivanić, D.; Stojanović, I.; Momčilović, M.; Maksimović, V.; Tufegdžić, S.; Marjanović, Ž.; Mostarica-Stojković, M.; Vučinić, Ž.; et al. Anti-Tumor Effect of Coriolus Versicolor Methanol Extract against Mouse B16 Melanoma Cells: In Vitro and in Vivo Study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Insights into Health-Promoting Effects of Jew’s Ear (Auricularia Auricula-Judae). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, M.; Thangavel, N.; Ali, A.; Shar, J.; Ali, B.; Alhabsi, F.; Mosa, S.; Ghazwani, S.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Najmi, A. Establishing Gerger ( Eruca Sativa ) Leaves as Functional Food by GC-MS and In-Vitro Anti-Lipid Peroxidation Assays. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 8, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Huang, M.; Fu, Y.; Qiao, M.; Li, Y. How Closely Does Induced Agarwood’s Biological Activity Resemble That of Wild Agarwood? Molecules 2023, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleno, S.A.; Barros, L.; João, M.; Martins, A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Tocopherols Composition of Portuguese Wild Mushrooms with Antioxidant Capacity. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Sbhatu, D.B. Investigation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Different Extracts of Auricularia and Termitomyces Species of Mushrooms. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, S.J.; Chen, F.; Ma, L.; Hu, X.; Ji, J. Functional Perspective of Black Fungi (Auricularia Auricula): Major Bioactive Components, Health Benefits and Potential Mechanisms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Sbhatu, D.B. Investigation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Different Extracts of Auricularia and Termitomyces Species of Mushrooms. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.R.; Rapior, S.; Mortimer, P.E.; Kakumyan, P.; Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J. A Review of the Polysaccharide, Protein and Selected Nutrient Content of Auricularia, and Their Potential Pharmacological Value. Mycosphere 2019, 10, 579–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsianti, A.; Rabbani, A.; Bahtiar, A.; Azizah, N.N.; Nadapdap, L.D.; Fajrin, M.; Arsianti, A.; Rabbani, A.; Nadapdap, L.D. Phytochemistry, Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Black-White Fungus Auricularia Sp. against Breast MCF-7 Cancer Cells. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caz, V.; Gil-Ramírez, A.; Largo, C.; Tabernero, M.; Santamaría, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Marín, F.R.; Reglero, G.; Soler-Rivas, C. Modulation of Cholesterol-Related Gene Expression by Dietary Fiber Fractions from Edible Mushrooms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7371–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, D.; Guan, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, X. Mushroom Polysaccharides with Potential in Anti-Diabetes: Biological Mechanisms, Extraction, and Future Perspectives: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Antidiabetic Mechanism of Dietary Polysaccharides Based on Their Gastrointestinal Functions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4781–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Jia, D.; Lu, W.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, L. Hpyerglycemic and Anti-Diabetic Nephritis Activities of Polysaccharides Separated from Auricularia Auricular in Diet-Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Hu, J.; Nie, Q.; Nie, S. Effects of Polysaccharides on Glycometabolism Based on Gut Microbiota Alteration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawangwan, T.; Wansanit, W.; Pattani, L.; Noysang, C. Study of Prebiotic Properties from Edible Mushroom Extraction. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2018, 52, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, R.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wong, G.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Relationship of Three Major Domesticated Varieties of Auricularia Auricula-Judae. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, W.; Xie, B.; Liu, H. Effects of Auricularia Auricula and Its Polysaccharide on Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia Rats by Modulating Gut Microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, X. Assessment of Auricularia Cornea Var. Li. Polysaccharides Potential to Improve Hepatic, Antioxidation and Intestinal Microecology in Rats with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. N 2023, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Bai, Y.; Zha, L.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, H.; Shah, S.R.H.; Sun, H.; Zhang, C. Mechanism of the Gut Microbiota Colonization Resistance and Enteric Pathogen Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of Short Chain Fatty Acids by the Gut Microbiota and Their Impact on Human Metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Besten, G.; Van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Interplay between Diet, Gut Microbiota, and Host Energy Metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Kujawowicz, K.; Witkowska, A.M. Beta-Glucans from Fungi: Biological and Health-Promoting Potential in the Covid-19 Pandemic Era. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, M.; Lu, X.; Narciso, J.O.; Li, W.; Qin, Y.; Brennan, M.A.; Brennan, C.S. Physical, Predictive Glycaemic Response and Antioxidative Properties of Black Ear Mushroom (Auricularia Auricula) Extrudates. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Men, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y. Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Exopolysaccharides from Submerged Culture of Auricularia Auricula-Judae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 64. Iebba V, Totino V, Gagliardi A, Santangelo F, Cacciotti F, Trancassini M, Mancini C, Cicerone C, Corazziari E, Pantanella F, Schippa S. Xue, Y.; Wei, J.; Huo, X.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, R.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. Eubiosis and Dysbiosis: The Two Sides of the Microbiota. New Microbiol. 2016, 39, 1–12.

- Liuzzi, G.M.; Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Crescenzi, A.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant Compounds from Edible Mushrooms as Potential Candidates for Treating Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wu, Q.; Liang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Shang, X. The Current State and Future Prospects of Auricularia Auricula’s Polysaccharide Processing Technology Portfolio. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Gao, Q.; Rong, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J. Immunomodulatory Effects of Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms and Their Bioactive Immunoregulatory Products. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, K. Evaluation of Water Soluble β-d-Glucan from Auricularia Auricular-Judae as Potential Anti-Tumor Agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falowo, A.B.; Muchenje, V.; Hugo, A.; Aiyegoro, O.A.; Fayemi, P.O. Actividades Antioxidantes de Extractos de Hoja de Moringa Oleifera L. y Bidens Pilosa L. y Sus Efectos En La Estabilidad Oxidativa de Ternera Cruda Picada Durante El Almacenamiento En Frío. CYTA - J. Food 2017, 15, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Amdekar, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V. Preliminary Study of the Antioxidant Properties of Flowers and Roots of Pyrostegia Venusta (Ker Gawl) Miers. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enisoglu-Atalay, V.; Atasever-Arslan, B.; Yaman, B.; Cebecioglu, R.; Kul, A.; Ozilhan, S.; Ozen, F.; Cata, T. Chemical and Molecular Characterization of Metabolites from Flavobacterium Sp. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, S.; Technical, R.; Agency, U.S.E.P. Provisional Peer-Reviewed Toxicity Values for Azodicarbonamide; 2014.

- Huang, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, Z.; Shi, K.; Zhang, C.; Shao, H. Phthalic Acid Esters: Natural Sources and Biological Activities. Toxins (Basel). 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sympli, H.D. Estimation of Drug - Likeness Properties of GC – MS Separated Bioactive Compounds in Rare Medicinal Pleione Maculata Using Molecular Docking Technique and SwissADME in Silico Tools. Netw. Model. Anal. Heal. Informatics Bioinforma. 2021, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathiya, S.; Kumar, B.S.; Devi, K. Phytochemical Screening and GC-MS Analysis of Cardiospermum Halicacabum L. Leaf Extract. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2018, 2, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Tona, M.R.; Sharmin, S.; Sayeed, M.A.; Tania, F.Z.; Paul, A.; Chy, N.U.; Rakib, A.; Emran, T. Bin; Simal-gandara, J. GC-MS Phytochemical Profiling, Pharmacological Properties, and In Silico Studies of Chukrasia Velutina Leaves: A Novel Source for Bioactive Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.; Kim, K.D. Effect of Temperature and Relative Humidity on Growth of Aspergillus and Penicillium Spp. and Biocontrol Activity of Pseudomonas Protegens AS15 against Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Flavus in Stored Rice Grains. Mycobiology 2018, 46, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ullah, F.; Sadiq, A.; Ayaz, M.; Imran, M.; Ali, I.; Zeb, A.; Ullah, F.; Shah, M.R. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Potentials of Essential Oil of Rumex Hastatus D. Don Collected from the North West of Pakistan. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, K.; Zheng, L.; Cai, H.; Cao, G.; Lou, Y.; Lu, T.; Shu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Cai, B. Characterization of Chemical Composition of Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae Volatile Oil by Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography with High-Resolution Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzano, A.; Ammar, M.; Papaianni, M.; Grauso, L.; Sabbah, M.; Capparelli, R.; Lanzotti, V. Moringa Oleifera Lam.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.J.; Omran, A.M.; Hussein, H.M. Antibacterial and Phytochemical Analysis of Piper Nigrum Using Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrum and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 977–996. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, E.; Henriques, M.; Soares, G. Cyclodextrin/Cellulose Hydrogel with Gallic Acid to Prevent Wound Infection. Cellulose 2014, 21, 4519–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Saranya, M.S.; Arunprasath, A. Evaluation of Phytochemical Compounds in Corbichonia Decumbens (Frossk). Excell by Using Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry. J. Appl. Adv. Res. 2019, 4, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Peng, Y.; Chung, W.; Chung, K.; Huang, H.; Huang, J. Inhibition of Penicillium Digitatum and Citrus Green Mold by Volatile Compounds Produced by Enterobacter Cloacae Plant Pathology & Microbiology. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranthaman, R.; Praveen, K.P.; Kumaravel, S. GC-MS Analysis of Phytochemicals and Simultaneous Determination of Flavonoids in Amaranthus Caudatus (Sirukeerai) by RP-HPLC. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2012, 03, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.C.F.; Gomes, L.A.; Silva, J.R.D.A.; Ferreira, J.L.P.; Ramos, A.D.S.; Rosa, M.D.S.S.; Vermelho, A.B.; Rodrigues, I.A. Liposomal Formulation of Turmerone-Rich Hexane Fractions from Curcuma Longa Enhances Their Antileishmanial Activity. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, P.P.; Lee, J.H.; Jun, H.S. Pancreatic Beta-Cell Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2023, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S. The Amazing Potential of Fungi : 50 Ways We Can Exploit Fungi Industrially. Fungal Divers. 2019, 97, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, J.; Sivanesan, I.; Muthu, M.; Oh, J.W. Scrutinizing the Nutritional Aspects of Asian Mushrooms, Its Commercialization and Scope for Value-Added Products. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, K.; Sreeja, P.S.; Yang, X. The Antioxidant Properties of Mushroom Polysaccharides Can Potentially Mitigate Oxidative Stress, Beta-Cell Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, J.A.; Mihailović, M.; Uskoković, A.; Grdović, N.; Dinić, S.; Vidaković, M. The Effects of Major Mushroom Bioactive Compounds on Mechanisms That Control Blood Glucose Level. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.T.; Wang, S.L.; Nguyen, V.B.; Kuo, Y.H. Isolation and Identification of Potent Antidiabetic Compounds from Antrodia Cinnamomea — An Edible Taiwanese Mushroom. Molecules 2018, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Jiao, C.; Xie, Y.; Ye, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, Q. Grifola Frondosa GF5000 Improves Insulin Resistance by Modulation the Composition of Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Rats. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, S. SX-Fraction: Promise for Novel Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, M.; He, Y.; Zhai, C.; Li, C. A Review on the Production, Structure, Bioactivities and Applications of Tremella Polysaccharides. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholola, M.T.; Adongbede, E.M.; Williams, L.L.; Adekunle, A.A. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Secondary Metabolites from Microporus Xanthopus (Fr.) Kuntze (Polypore) Collected from the Wild in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2022, 26, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Berhe Sbhatu, D. Determination of Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts of Indigenous Wild Mushrooms against Pathogenic Organisms. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, S.; Puska, P.; Norrving, B. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control; 2011; ISBN 978 92 4 156437 3.

- Rauf, A.; Joshi, P.B.; Ahmad, Z.; Hemeg, H.A.; Olatunde, A.; Naz, S.; Hafeez, N.; Simal-Gandara, J. Edible Mushrooms as Potential Functional Foods in Amelioration of Hypertension. Phyther. Res. 2023, 37, 2644–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aline Mayrink, de M. Agaricus Brasiliensis (Sun Mushroom) and Its Therapeutic Potential: A Review. Arch. Food Nutr. Sci. 2022, 6, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, A.H.; Rehman, S.; Kiron, V.; Dias, J.; Fernandes, J.M.O.; Olsvik, P.A.; Siriyappagouder, P.; Vatsos, I.; Schmid-Staiger, U.; Frick, K.; et al. Management of Hypercholesterolemia Through Dietary SS-Glucans–Insights From a Zebrafish Model. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyama, R. DNA Microarray-Based Screening and Characterization of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Microarrays 2017, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Kumari, S.; Attri, C.; Sharma, R.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Benali, T.; Bouyahya, A.; Gürer, E.S.; Sharifi-Rad, J. GC-MS Analysis, Antioxidant and Antifungal Studies of Different Extracts of Chaetomium Globosum Isolated from Urginea Indica. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, D.; Abraham, J. In Vitro Analysis of Antimicrobial Compounds from Euphorbia Milli. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2022, 16, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.G.; Badr, A.N.; El Sohaimy, S.A.; Asker, D.; Awad, T.S. Characterization of Antifungal Metabolites Produced by Novel Lactic Acid Bacterium and Their Potential Application as Food Biopreservatives. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuerich, M.; Petrussa, E.; Filippi, A.; Cluzet, S.; Fonayet, J.V.; Sepulcri, A.; Piani, B.; Braidot, E. Antifungal Activity of Chili Pepper Extract with Potential for the Control of Some Major Pathogens in Grapevine. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.A.H.; Thabet, A.Z.A.; Alarabi, F.Y.S.; Omar, G.M.N. Analysis of Bioactive Chemical Compounds of Leaves Extracts from Tamarindus Indica Using FT-IR and GC-MS Spectroscopy. Asian J. Res. Biochem. 2021, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, S.R. Antibacterial Potential of White Crystalline Solid from Red Algae Porteiria Hornemanii against the Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. African J. Agric. Reseearch 2014, 9, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciences, B.; Gheda, S.F.; Ismail, G.A. Natural Products from Some Soil Cyanobacterial Extracts with Potent Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities. An Acad Bras Cienc 2020, 92, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikadevi, T.; Paulsamy, S.; Jamuna, S.; Karthika, K. Analysis for Phytoceuticals and Bioinformatics Approach for the Evaluation of Therapetic Properties of Whole Plant Methanolic Extract of Mukia Maderaspatana (L.) M.Roem. (Cucurbitaceae) - A Traditional Medicinal Plant in Western Districts of Tamil Nadu, I. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2012, 5, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, V.; Jananie, R.K.; Vijayalakshmi, K. GC/MS Determination of Bioactive Components of Trigonella Foenum Grecum. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2011, 3, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schrag, A.; Carroll, C.; Duncan, G.; Molloy, S.; Grover, L.; Hunter, R.; Brown, R.; Freemantle, N.; Whipps, J. Antidepressants Trial in Parkinson ’ s Disease ( ADepT - PD ): Protocol for a Randomised Placebo - Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness of Escitalopram and Nortriptyline on Depressive Symptoms in Parkinson ’ s Disease. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Singh, V.; Thakral, S. Synthesis, in Silico Studies and Biological Screening of (E)-2-(3-(Substitutedstyryl)-5-(Substitutedphenyl)-4,5-Dihydropyrazol-1-Yl)Benzo[d]Thiazole Derivatives as an Anti-Oxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Agents. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheda, S.F.; Abo-Shady, A.M.; Abdel-Karim, O.H.; Ismail, G.A. Antioxidant and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Arthrospira Platensis (Spirulina Platensis) Methanolic Extract: In Vitro and in Vivo Study. Egypt. J. Bot. 2021, 61, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F Bobade, A. GC-MS Analysis of Bioactive Compound in Ethanolic Extract of Pithecellobium Dulce Leaves. Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 3, 08–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoramoorthy, G.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Venkatesalu, V.; Hsu, M.J. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters of the Blind-Your-Eye Mangrove from India. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2007, 38, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameem, S.A.; Ganai, B.A.; Rather, M.S.; Khan, K.Z. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Viscum Album L. Growing on Juglans Regia Host Tree in Kashmir, India. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. 2017, 6, 921–927. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, N.; Lipsky, R.H.; Bourourou, M.; Duncan, M.W.; Gorelick, P.B.; Marini, A.M. Alpha-Linolenic Acid: An Omega-3 Fatty Acid with Neuroprotective Properties - Ready for Use in the Stroke Clinic? Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelliah, R.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Antony, U. Nutritional Quality of Moringa Oleifera for Its Bioactivity and Antibacterial Properties. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 825–833. [Google Scholar]

- Murru, E.; Manca, C.; Carta, G.; Banni, S. Impact of Dietary Palmitic Acid on Lipid Metabolism. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguanphun, T.; Promtang, S.; Sornkaew, N.; Niamnont, N.; Sobhon, P. Anti-Parkinson Effects of Holothuria Leucospilota -Derived Palmitic Acid in Caenorhabditis Elegans Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesga-jiménez, D.J.; Martin, C.; Barreto, G.E.; Aristizábal-pachón, A.F.; Pinzón, A.; González, J. Fatty Acids: An Insight into the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larayetan, R.; Ololade, Z.S.; Ogunmola, O.O.; Ladokun, A. Phytochemical Constituents, Antioxidant, Cytotoxicity, Antimicrobial, Antitrypanosomal, and Antimalarial Potentials of the Crude Extracts of Callistemon Citrinus. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.F.; Mahmoud, G.A.E.; Hefzy, M.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C. Overview on the Edible Mushrooms in Egypt. J. Futur. Foods 2023, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Chopra, H.; Baig, A.A.; Avula, S.K.; Kumari, S.; Mohanta, T.K.; Saravanan, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Sharma, N.; Mohanta, Y.K. Edible Mushrooms as Novel Myco-Therapeutics: Effects on Lipid Level, Obesity, and BMI. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Yang, M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Sun, Q.; Chavarro, J.E. Mushroom Consumption, Biomarkers, and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study of US Women and Men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Asif, M.; Hasan, G.M.M.A. A Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Compositions of Three Cultivated Edible Mushroom Species of Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, Y.; Pintel, N.; Khattib, H.; Shagug, N.; Taha, R.; Avni, D. Regulation of Cholesterol Metabolism by Phytochemicals Derived from Algae and Edible Mushrooms in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhi, N.T.N.; Khang, D.T.; Dung, T.N. Termitomyces Mushroom Extracts and Its Biological Activities. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitati, C.N.W.; Ogila, K.O.; Waihenya, R.W.; Ochola, L.A. Phytochemical Profile and Antimicrobial Activities of Edible Mushroom Termitomyces Striatus. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, M.E.; Martínez-Carrera, D.; Torres, N.; Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Aguilar-López, M.; Morales, P.; Sobal, M.; Bernabé, T.; Escudero, H.; Granados-Portillo, O.; et al. Hypocholesterolemic Properties and Prebiotic Effects of Mexican Ganoderma Lucidum in C57BL/6 Mice. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, S.; Rathee, D.; Rathee, D.; Kumar, V.; Rathee, P. Mushrooms as Therapeutic Agents. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012, 22, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabubuya, A.; Muyonga, J.; Kabasa, J. Nutritional and Hypocholesterolemic Properties of Termitomyces Microcarpus Mushrooms. African J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2010, 10, 2235–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, N.F.M.; Aminudin, N.; Abdullah, N. Pleurotus Pulmonarius (Fr.) Quel Crude Aqueous Extract Ameliorates Wistar-Kyoto Rat Thoracic Aortic Tissues and Vasodilation Responses. Sains Malaysiana 2022, 51, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.A.M.; Imad, H.H.; Salah, A.I. Analysis of Bioactive Chemical Components of Two Medicinal Plants (Coriandrum Sativum and Melia Azedarach) Leaves Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). African J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 2812–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudehi, M.F.; Ardalan, A.A.; Zibaseresht, R. Chemical Constituents of an Iranian Grown Capsicum Annuum and Their Cytotoxic Activities Evaluation. Org. Med. Chem IJ 2020, 9, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, J.O.; Akomaye, F.A.; Markson, A.A.; Egwu, A.C. GC-MS Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in Some Wild-Edible Mushrooms from Calabar, Southern Nigeria. Eur. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sui, Y.; Chen, S. Detection of Flavor Compounds in Longissimus Muscle from Four Hybrid Pig Breeds of Sus Scrofa, Bamei Pig, and Large White. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 1910–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineshkumar, G.; Rajakumar, R. GC-MS EVALUATION OF BIOACTIVE MOLECULES FROM THE METHANOLIC LEAF EXTRACT OF AZADIRACHTA INDICA ( A. JUSS ). Asian J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. www.ajpst.com 2015, 5, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ahire, J.J.; Dicks, L.M.T. nhibit Biofilm Formation by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. 2014, 58, 2098–2104. [CrossRef]

- Stastny, J.; Marsik, P.; Tauchen, J.; Bozik, M.; Mascellani, A.; Havlik, J.; Landa, P.; Jablonsky, I.; Treml, J.; Herczogova, P.; et al. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Five Medicinal Mushrooms of the Genus Pleurotus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustika, D.K.; Mercuriani, I.S.; Ariyanti, N.A.; Purnomo, C.W.; Triyana, K.; Iliescu, D.D.; Leeson, M.S. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Compounds Emitted by Pepper Yellow Leaf Curl Virus-Infected Chili Plants: A Preliminary Study. Separations 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingole, S.N. Phytochemical Analysis of Leaf Extract of Ocimum Americanum L. ( Lamiaceae ) by GCMS Method. World Sci. News 2016, 37, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Belinda, N.S.; Swaleh, S.; Mwonjoria, K.J.; Wilson, M.N. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content of Selected Kenyan Medicinal Plants, Sea Algae and Medicinal Wild Mushrooms. African J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 13, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Phenolic Profiles and Antioxidant Activities in Selected Drought-Tolerant Leafy Vegetable Amaranth. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardini, M.; Garaguso, I. Characterization of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Fruit Beers. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Sbhatu, D.B. Challenges of Intervention, Treatment, and Antibiotic Resistance of Biofilm-Forming Microorganisms. Heliyon 2019, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.P.; Gulotta, G.; do Amaral, M.W.; Lünsdorf, H.; Sasse, F.; Abraham, W.R. Coprinuslactone Protects the Edible Mushroom Coprinus Comatus against Biofilm Infections by Blocking Both Quorum-Sensing and MurA. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4254–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawas, S.; Verderosa, A.D.; Totsika, M. Combination Therapies for Biofilm Inhibition and Eradication: A Comparative Review of Laboratory and Preclinical Studies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Sahoo, G.; Swain, S.S.; Luyten, W. Anticancer Activities of Mushrooms: A Neglected Source for Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esheli, M.; Thissera, B.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Rateb, M.E. Fungal Metabolites in Human Health and Diseases—An Overview. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazir, J.; Riley, D.L.; Pilcher, L.A.; De-Maayer, P.; Mir, B.A. Anticancer Agents from Diverse Natural Sources. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.; Davies, D.M. CAR-Based Immunotherapy of Solid Tumours—A Survey of the Emerging Targets. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Arévalo, J.; Sánchez, J.E.; González-Cortázar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; Andrade-Gallegos, R.H.; Mendoza-De-Gives, P.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. Chemical Composition of an Anthelmintic Fraction of Pleurotus Eryngii against Eggs and Infective Larvae (L3) of Haemonchus Contortus. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.H.; Yang, C.T.; Chang, H.Y.; Hsueh, Y.P.; Hsu, C.C. Nematode-Trapping Fungi Produce Diverse Metabolites during Predator–Prey Interaction. Metabolites 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.K.; Das, R.; Mai, A.H.; De Borggraeve, W.M.; Luyten, W. Nematicidal Activity of Holigarna Caustica (Dennst.) Oken Fruit Is Due to Linoleic Acid. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkirui, C.; Cheng, T.; Matasyoh, J.; Decock, C.; Stadler, M. An Unprecedented Spiro [Furan-2,1’-Indene]-3-One Derivative and Other Nematicidal and Antimicrobial Metabolites from Sanghuangporus Sp. (Hymenochaetaceae, Basidiomycota) Collected in Kenya. Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 25, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, S.; Helaly, S.; Schroers, H.J.; Stadler, M.; Richert-Poeggeler, K.R.; Dababat, A.A.; Maier, W. Ijuhya Vitellina Sp. Nov., a Novel Source for Chaetoglobosin A, Is a Destructive Parasite of the Cereal Cyst Nematode Heterodera Filipjevi; 2017; Vol. 12; ISBN 1111111111.

- Inoue, T.; Shingaki, R.; Fukui, K. Inhibition of Swarming Motility of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Branched-Chain Fatty Acids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, G.; Khadijeh, B.; Hossein, D. Essential Oil Composition of Two Scutellaria Species from Iran. J. Tradit. Chinese Med. Sci. 2019, 6, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, T.; Middha, S.K.; Shanmugarajan, D.; Babu, D.; Goyal, A.K.; Yusufoglu, H.S.; Sidhalinghamurthy, K.R. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Metabolic Profiling, Molecular Simulation and Dynamics of Diverse Phytochemicals of Punica Granatum L. Leaves against Estrogen Receptor. Front. Biosci. 2021, 26, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lin, J.; He, Y.; Liu, S. Polysaccharide-Peptide from Trametes Versicolor: The Potential Medicine for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.W.; Yue, G.G.L.; Ko, C.H.; Lee, J.K.M.; Gao, S.; Li, L.F.; Li, G.; Fung, K.P.; Leung, P.C.; Lau, C.B.S. In Vivo and in Vitro Anti-Tumor and Anti-Metastasis Effects of Coriolus Versicolor Aqueous Extract on Mouse Mammary 4T1 Carcinoma. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, D.; Patel, S.; Kim, S.K. Anticancer and Other Therapeutic Relevance of Mushroom Polysaccharides: A Holistic Appraisal. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, T.; Agarwal, M. Phytochemical Screening and GC-MS Analysis of Bioactive Constituents in the Ethanolic Extract of Pistia Stratiotes L. and Eichhornia Crassipes ( Mart.) Solms. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaveni, M.; Dhanalakshmi, R.; Nandhini, N. GC-MS Analysis of Phytochemicals, Fatty Acid Profile, Antimicrobial Activity of Gossypium Seeds. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014, 27, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Shirvani, A.; Jafari, M.; Goli, S.A.H.; Soltani Tehrani, N.; Rahimmalek, M. The Changes in Proximate Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Fatty Acid Profile of Germinating Safflower (Carthamus Tinctorius) Seed. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2016, 18, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeropoulos, N.; Yanni, A.E.; Koutrotsios, G.; Aloupi, M. Bioactive Microconstituents and Antioxidant Properties of Wild Edible Mushrooms from the Island of Lesvos, Greece. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malash, M.A.; El-Naggar, M.M.A.; Ibrahim, M.S. Antimicrobial Activities of a Novel Marine Streptomyces Sp. MMM2 Isolated from El-Arish Coast, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2022, 26, 1317–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyalo, P.; Omwenga, G.; Ngugi, M. Quantitative Phytochemical Profile and In Vitro Antioxidant Properties of Ethyl Acetate Extracts of Xerophyta Spekei (Baker) and Grewia Tembensis (Fresen). J. evidence-based Integr. Med. 2023, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.; Pandey, S.C.; Maiti, P.; Tripathi, M.; Paliwal, A.; Nand, M.; Sharma, P.; Samant, M.; Pande, V.; Chandra, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Methanolic Extracts of Vernonia Cinerea against Xanthomonas Oryzae and Identification of Their Compounds Using in Silico Techniques. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczak, A.; Ożarowski, M.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Activity of Some Flavonoids and Organic Acids Widely Distributed in Plants. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, J. Morphological and Molecular Systematics of Resupinatus (Basidiomycota), 2015.

- Phukhamsakda, C.; Nilsson, R.H.; Bhunjun, C.S.; de Farias, A.R.G.; Sun, Y.R.; Wijesinghe, S.N.; Raza, M.; Bao, D.F.; Lu, L.; Tibpromma, S.; et al. The Numbers of Fungi: Contributions from Traditional Taxonomic Studies and Challenges of Metabarcoding. Fungal Divers. 2022, 114, 327–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwulski, M.; Rzymski, P.; Budka, A. Screening the Multi-Element Content of Pleurotus Mushroom Species Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer ( ICP-OES ). Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczek, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Kalač, P.; Budka, A.; Siwulski, M.; Gąsecka, M.; Rzymski, P.; Magdziak, Z.; Sobieralski, K. Multielemental Analysis of 20 Mushroom Species Growing near a Heavily Trafficked Road in Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 16280–16295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T. ITS Primers with Enhanced Specificity for Basidiomycetes - Application to the Identification of Mycorrhizae and Rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaw, S.; Albinto, R. Functional Activities of Philippine Wild Strain of Coprinus Comatus (O.F.Müll.: Fr.) Pers and Pleurotus Cystidiosus O. K. Miller Grown on Rice Straw Based Substrate Formulation. Mycosphere 2014, 5, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandati, T.W.; Kenji, G.M.; Onguso, J.M. Phytochemicals in Edible Wild Mushrooms From Selected Areas in Kenya. J. Food Res. 2013, 2, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, S.X.; Zhang, S.S.; Cao, C.X. Inhibiting Effect of Bioactive Metabolites Produced by Mushroom Cultivation on Bacterial Quorum Sensing-Regulated Behaviors. Chemotherapy 2011, 57, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wei, L.; Xian, W.S.; Zhen, T.B.; Shuai, Z.S. Evaluation of Anti-Quorum-Sensing Activity of Fermentation Metabolites from Different Strains of a Medicinal Mushroom, Phellinus Igniarius. Chemotherapy 2012, 58, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, V.; Jananie, R.; Vijayalakshmi, K. GC-Ms Determination of Bioactive Components of Pleurotus Ostreatus. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012, 3, 150–151. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).