Introduction

Motivated by national and international environmental policies, ongoing research endeavors are focused on developing methods to produce environmentally friendly materials that can be effectively managed at the end of their useful life. This goal primarily involves refining their responsiveness to biological degradation processes (Magnin et al., 2019; Zuliani et al., 2022; Gogoi et al.).

Among the wide range of resilient plastic materials, polyurethanes (PUs) stand out as a versatile family of synthetic polymers extensively employed in various applications. PUs contain a urethane functional group (-NHC(=O)-O) formed through the reaction between the isocyanate group and the hydroxy group. However, their chemical recycling faces limitations due to the high processing temperature required, leading to high energy consumption, and the occurrence of side chemical reactions on the urethane bond (Gadhave et al., 2019; Kemona et al., 2020). Biological recycling, on the other hand, is a promising route with high potential to address the need for PU recycling in the coming years (Kim et al., 2022; Spontón et al., 2013). It is a gentle process that can be implemented at low temperatures, below 70°C. In biological recycling, microorganisms secrete enzymes that break down complex organic molecules into smaller components, which can be absorbed and utilized by the organisms for their growth and metabolism. While PUs are partly sensitive to biological degradation, such as the biodegradation of the ester bond within the urethane group by naturally occurring microorganisms, they do not meet the requirements of the European norm EN 13432, which defines biodegradable and compostable materials (Wierckx et al., 2018; Zuliani et al., 2022; Magnin et al., 2019). According to this norm, a material is deemed biodegradable if its mass loss reaches 90% within a 6-month period under composting conditions. In addition to the transformation of polymer materials into products consumed by microorganisms, leading to the generation of CO2 and H2O and the disappearance of material mass, they can also undergo depolymerization through enzyme-catalyzed processes. This allows for the valorization of degradation products. An example of successful enzymatic depolymerization is the efficient breakdown of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) at 60°C, resulting in the production of valuable building blocks like terephthalic acid and mono(2-hydroxyethyl)-terephthalate (Gamerith et al., 2017). This achievement with PET can serve as a benchmark for evaluating similar processes with polyurethane materials.

The initial scientific publications on PU biodegradability aimed to evaluate the vulnerability of PU formulations to microbial degradation for the purpose of creating durable materials. However, the current emphasis has shifted towards addressing the challenges related to the end-of-life handling of PU materials. Like other polymers, the microbial degradation of polyurethanes is influenced by factors such as crystallinity, cross-linking, and chemical structure (Oprea et al, 2010; Magnin et al., 2019; Zuliani et al., 2022). This study represents the first investigation into the biodegradation susceptibility of innovative and more environmentally conscious PUs that incorporate tree bark extractives as integral building blocks. The PUs were synthesized through the copolymerization of polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate and polyols using the casting method, with tetrahydrofuran as the solvent. The conventional fossil-based polyether PEG 400 polyol was partially or completely replaced with a diverse biopolyol composition. This composition consists of hydrophilic extractives, all bearing hydroxy functional groups, isolated from black alder bark, such as oregonin and other diarylheptanoids, proanthocyanidins, and carbohydrates. This substitution facilitates the attainment of bio-based content levels in the PU formulations, reaching up to 50% depending on NCO/OH ratio.

Experimental

Polyurethane degradation in sewage water as an inoculum source

Rectangular strips of polyurethane (PU) films with various formulations were prepared, measuring approximately 1 cm x 7 cm. Prior to the experiment, the specimens underwent meticulous drying to eliminate any residual moisture. The dried PU film strips were then weighed using a precise analytical scale with a resolution of 0.0001 g.

The methodology for assessing the biodegradation of PUs in sewage water using it as an inoculum source was adapted from a previous study by Nabeoka et al. (2021). The sewage water sourced from the active area of the "Getliņi Eco Ltd" landfill site underwent coarse filtration to eliminate large debris and particulate matter. Sewage water contains a diverse microbial community that can serve as an inoculum to initiate and drive the biodegradation process. The microorganisms present in sewage water have the potential to degrade various organic compounds, including polyurethane. According to the results of the sewage water analysis provided by "Getliņi Eco Ltd," it has been found that the water contains minerals that can support the growth of microorganisms. For instance, ammonia salts are present at approximately 1000 mg·L-1 of total nitrogen, and phosphates are present at approximately 15 mg·L-1 of total phosphorus.

Each experimental setup consisted of a glass vial filled with 100 mL of the sewage water and 0.3-0.7 g of carefully prepared PU film strips. To monitor biological oxygen consumption over time, the Respirometric BOD System, specifically the WTW OxiTop® was employed. This system facilitated continuous monitoring of pressure changes within the experimental setup, resulting from oxygen consumption by aerobic microorganisms. The released CO2 was consistently adsorbed by alkali granules placed in a special vessel, effectively preventing its impact on the pressure readings. The experimental setups were incubated at a constant temperature of 21 ℃ using the WTW OxiTop® Incubator Box, which was designed to provide a homogeneous environment for BOD Measurement Systems. The incubator ensured continuous mixing, guaranteeing uniform exposure of the PU films to the microbial population. The biodegradation experiment was conducted over a period of 60 days. To sustain optimal aerobic conditions for microbial activity, the sealed vials were opened every three days. This allowed for the introduction of additional oxygen into the biodegradation system, promoting the growth and metabolic activity of aerobic microorganisms. Additionally, the alkali pellets within the setup were replaced during each opening to maintain their effective adsorption capacity. A blank sample, consisting of 100 mL of sewage water without any added material, served as a reference to establish the baseline for measuring biological oxygen demand. For comparative analysis and validation, a biodegradable film conforming to the EU standard EN 13432 was utilized as a positive control.

Each experiment involving the PU films, blank sample, and positive control was conducted with three repetitions.

Upon completion of the 60-day experiment, the specimens were carefully removed from the sewage water, followed by thorough washing to eliminate any adhered residues. Subsequently, the washed PU film strips were dried at a controlled temperature of 60℃ for 48 hours, ensuring complete removal of any remaining moisture. The dry strips were then reweighed using the same analytical scale, and the weight loss for each PU film specimen was calculated as a percentage of its initial weight.

Polyurethane degradation through soil burial test

Rectangular strips of polyurethane (PU) films, measuring approximately 1 cm x 7 cm, were prepared for various polyurethane samples with different formulations. To ensure the absence of residual moisture, meticulous drying was performed on the specimens before the experiment. The dried PU film strips were then weighed using a precise analytical scale with a resolution of 0.0001 g.

The methodology for conducting soil burial tests to assess the biodegradation of PUs was adapted from a previous study by Pischedda et al. (2019). For the soil burial tests, Biolan, a commercially available peat-based soil from Finland, was selected. The soil was supplemented with magnesium-containing limestone powder (4 kg/m³) and had the following nutrient content: nitrogen soluble in water (1300 mg/kg dry matter), phosphorus soluble in water (840 mg/kg dry matter), potassium soluble in water (4200 mg/kg dry matter). Furthermore, the soil exhibited a pH of 6.5, electrical conductivity of 40 mS/m, bulk density of 300 g/l, moisture content of 60%, and a fraction size of <35 mm.

To enhance the presence of biodegrading microorganisms, compost derived from "Getiņi Eco Ltd." landfill was added (40 g/kg) and thoroughly mixed with the peat-based soil. Each replication consisted of 0.3-0.7 g of the prepared PU specimen, which was then combined with 30-70 g of soil in a 500 ml polypropylene jar. The jars were sealed with caps featuring holes to facilitate oxygen access. Additionally, a reference material in the form of a biodegradable PLA film, conforming to the EU standard EN 13432, was included. Each test and reference material underwent three replications. The jars were subsequently incubated in the dark at a temperature of 21 ± 2 ℃. The biodegradation experiment spanned a duration of 60 days. To maintain adequate moisture levels in the biodegradation system, 20 mL of tap water was added to each jar every 7 days.

Upon completion of the 60-day experiment, the specimens were carefully extracted from the soil and thoroughly washed to eliminate any adhered residues. Subsequently, the washed PU film strips were dried at a controlled temperature of 60℃ for 48 hours to ensure complete removal of any remaining moisture. The dry strips were then reweighed using the same analytical scale, and the weight loss of each PU film specimen was calculated as a percentage of its initial weight.

In addition, the specimens were cryogenically ground and analyzed using FTIR, Py-GC/MS/FID, and TG/DTG/DSC techniques.

Results and Discussion

During this study, the susceptibility to biodegradation of bio-based polyurethanes containing 40% and 50% hydroxyl groups-bearing black alder bark extractives as integral building blocks, replacing PEG 400, was compared to that of 100% fossil-based PU. The synthesized PUs films were subjected to a degradation period of 2 months in sewage water and compost-enriched soil, serving as media and sources of biodegrading microorganisms. For comparison, a commercially available PLA-based biodegradable film that meets the criteria specified in the European norm EN 13432 was used as a reference.

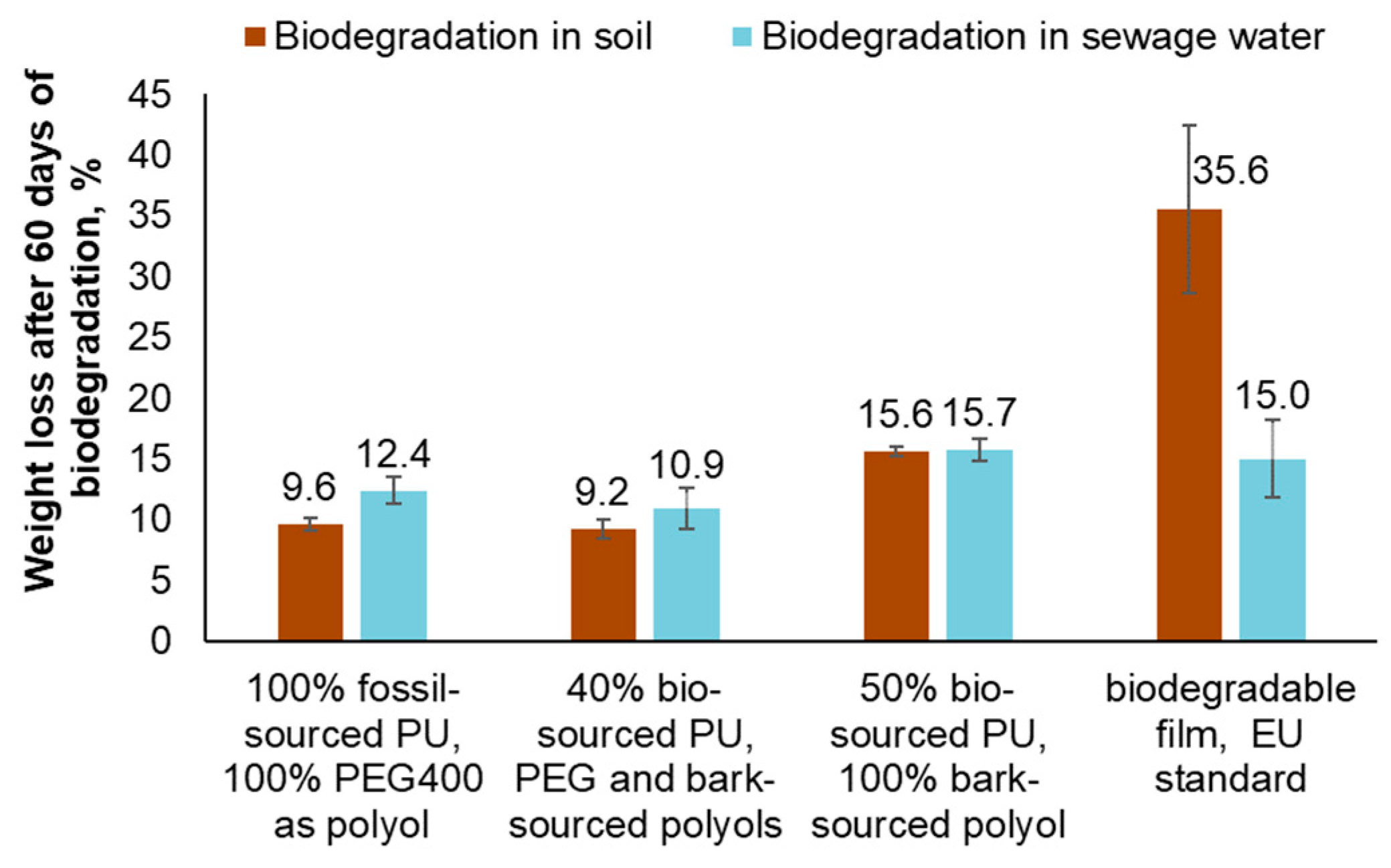

Following the 2-month biodegradation period in soil and sewage water, the PU synthesized using conventional fossil-based building blocks experienced weight losses of 9.6% and 12.4% respectively. However, with the complete replacement of PEG400 by bark-sourced polyol, the weight loss of the PU after biodegradation increased to 15.6% in soil and 15.7% in water. In contrast, the reference biodegradable film exhibited weight losses of 35.6% in soil and only 15.0% in sewage water (

Figure 1). Since the PLA-based film was specifically designed for degradation in compost environments, it did not exhibit a more significant mass loss compared to the PU in sewage water. This highlights the importance of selecting appropriate biodegradation conditions, which have not been previously studied or adjusted for the bark-sourced PU.

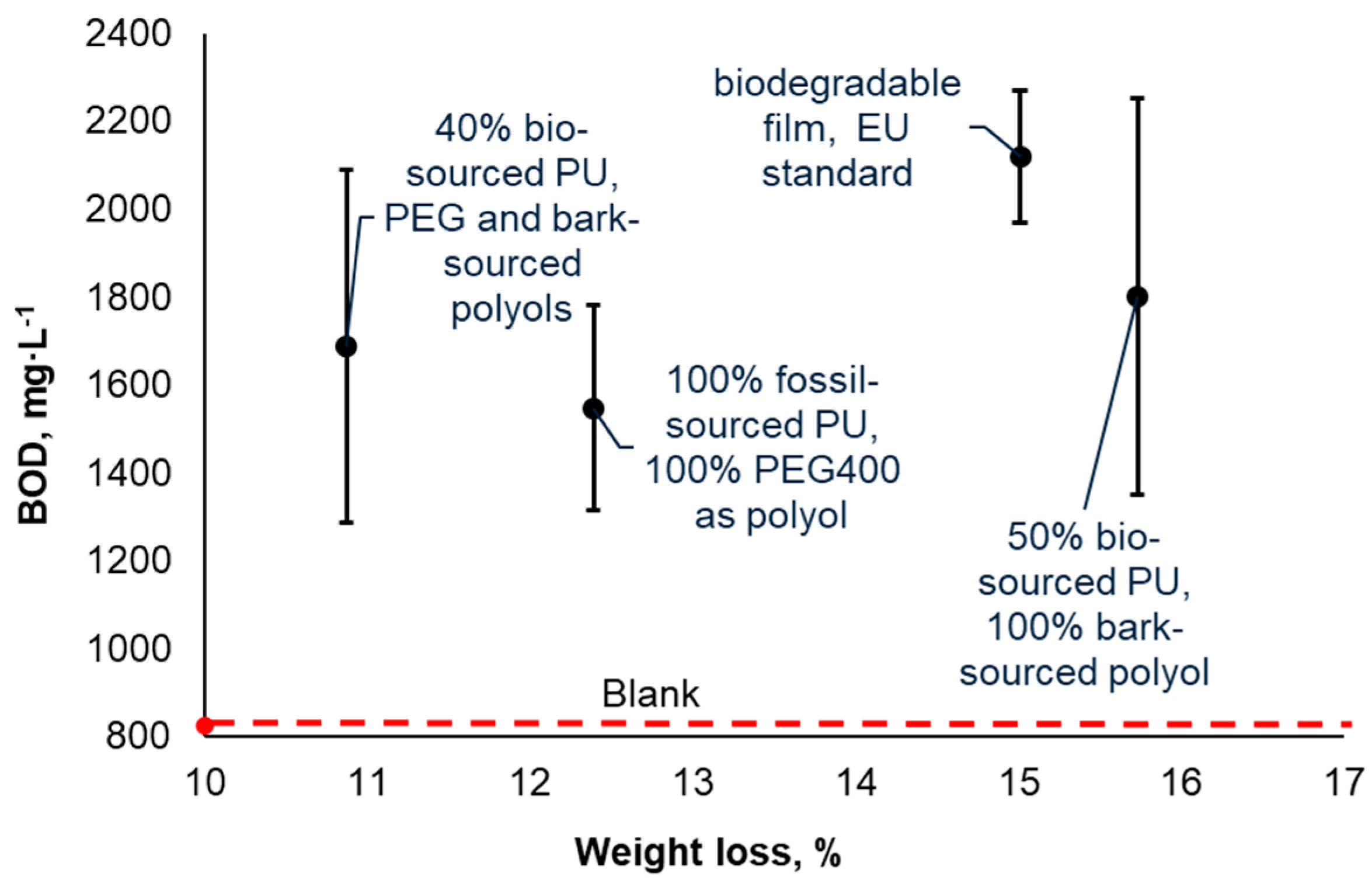

The cumulative biological oxygen demand (BOD) after 60 days of biodegradation in sewage water is considerably higher for PU materials compared to the blank sample (biodegradation system without added material specimens) (

Figure 2). This observation suggests that microorganisms are capable of utilizing PU as a source of support for their metabolism, corroborating previous findings (Gunawan et al., 2022). It is important to note that BOD values do not correlate with the mass loss of the materials, as demonstrated in

Figure 2. This implies that the activity of microorganisms not only results in the conversion of materials into CO

2 and H

2O but also induces chemical changes in the materials without a substantial loss of mass. Additionally, this can be explained by the generation of other volatile byproducts apart from CO

2.

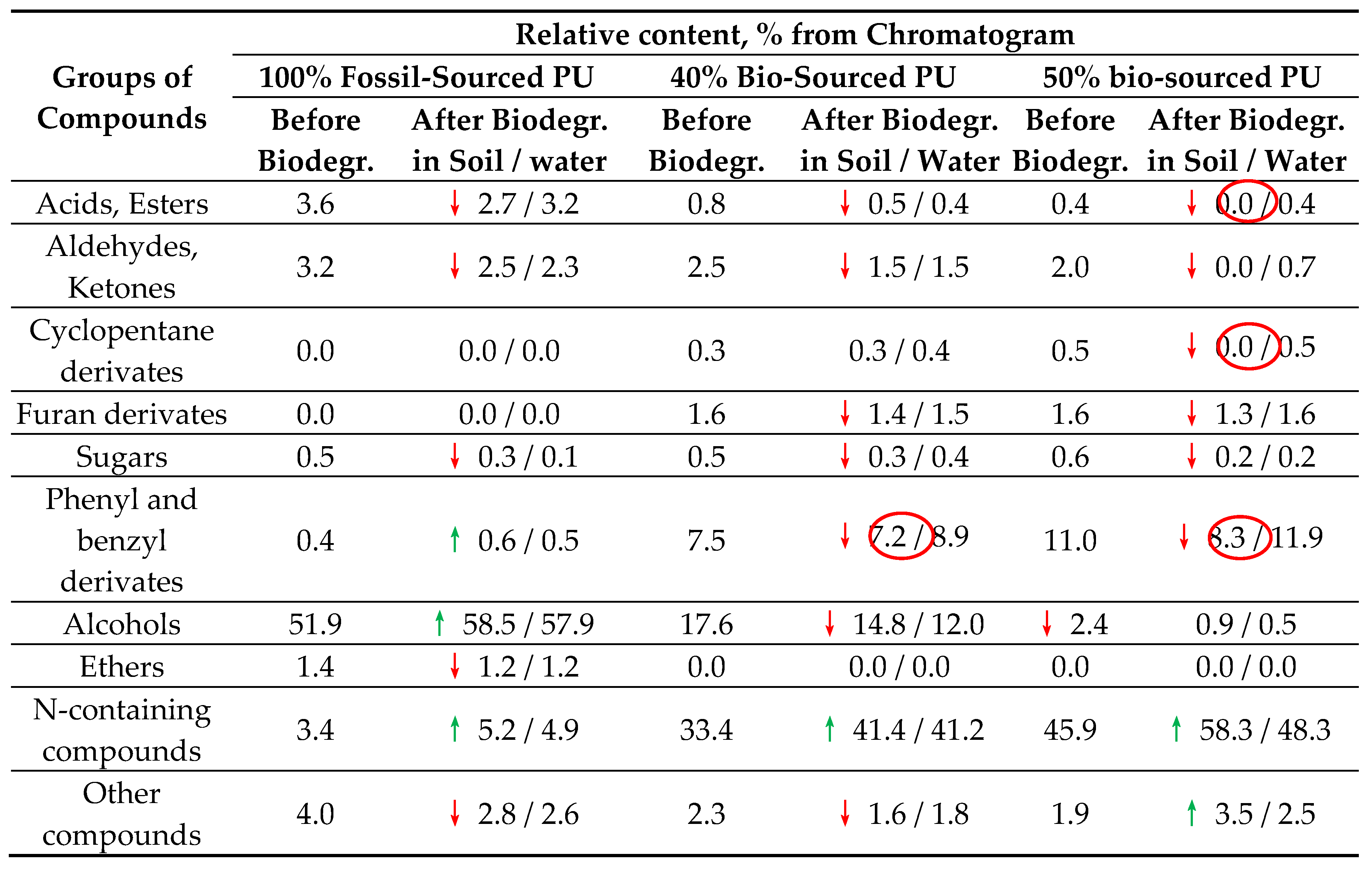

The Py-GC-MS/FID analysis allowed for a comprehensive examination of changes in PU materials after biodegradation. This was achieved by subjecting the sample to thermal degradation, resulting in the generation of a complex mixture of volatile products. The analysis method enabled the simultaneous identification of compounds derived from the thermal degradation of PEG400, building blocks sourced from bark, reacted isocyanates, and formed urethane linkages. The compounds associated with the urethane linkage were classified as N-containing compounds, such as aniline, diaminodiphenylmethane, 1-isocyanato-4-methyl-benzene etc. Ethers such as ethyl glycidyl ether, (2-ethoxy-1-methoxyethoxy)-ethene, bis-1,1'-[oxybis(2,1-ethanediyloxy)]-ethene etc. were derived from PEG400. Furan and cyclopentane derivatives were formed from bark-sourced building blocks. Other identified compounds, such as acids, esters, aldehydes, ketones, sugars, phenyl and benzyl derivatives were not specific to a particular building block within the PU network. While the content of most of the aforementioned aliphatic compounds decreases after biodegradation, only the content of phenyl and benzyl derivatives decreases in the case of biodegradation of PU incorporating bio-sourced polyols in soil. This indicates the higher stability of aromatic units in PU networks. However, bark-sourced aromatics are susceptible to biodegradation by soil microorganisms (

Table 1). The increase in the content of N-containing compounds in the pyrolysis products indicates the highest stability of the urethane linkage compared to other linkages and functional groups within the PU network, resulting in their concentration after the degradation of other PU building blocks.

Despite biodegradation in sewage water causing equal or higher mass loss for the polyurethanes under study (

Figure 1), the results of analytical pyrolysis reveal more significant changes in the structure of the PU network after biodegradation in soil. These changes include the degradation of aromatic building blocks in bio-sourced PUs, as evidenced by the decrease in the content of phenyl and benzyl derivatives in the pyrolysis products. The ratio of N-containing compounds associated with isocyanate building blocks in the PU network to phenyl and benzyl derivatives associated with both isocyanate and bark-sourced aromatic building blocks does not change after biodegradation of 100% fossil-derived PU films in both soil and water, as well as for partly bio-sourced PU films after their biodegradation in water. However, after biodegradation in soil of bark-sourced polyurethanes, this ratio increases from 4.5 to 5.8 and from 4.2 to 7.0 for 40% and 50% bio-sourced PUs, respectively (

Table 1). Furthermore, the 50% bio-sourced PU film, synthesized with 100% substitution of PEG400 by bark-derived polyol, exhibits the disappearance of carbohydrates-derived pyrolysis products of cyclopentane nature, as well as the disappearance of acids, esters, aldehydes, and ketones in the pyrolysis products (

Table 1).

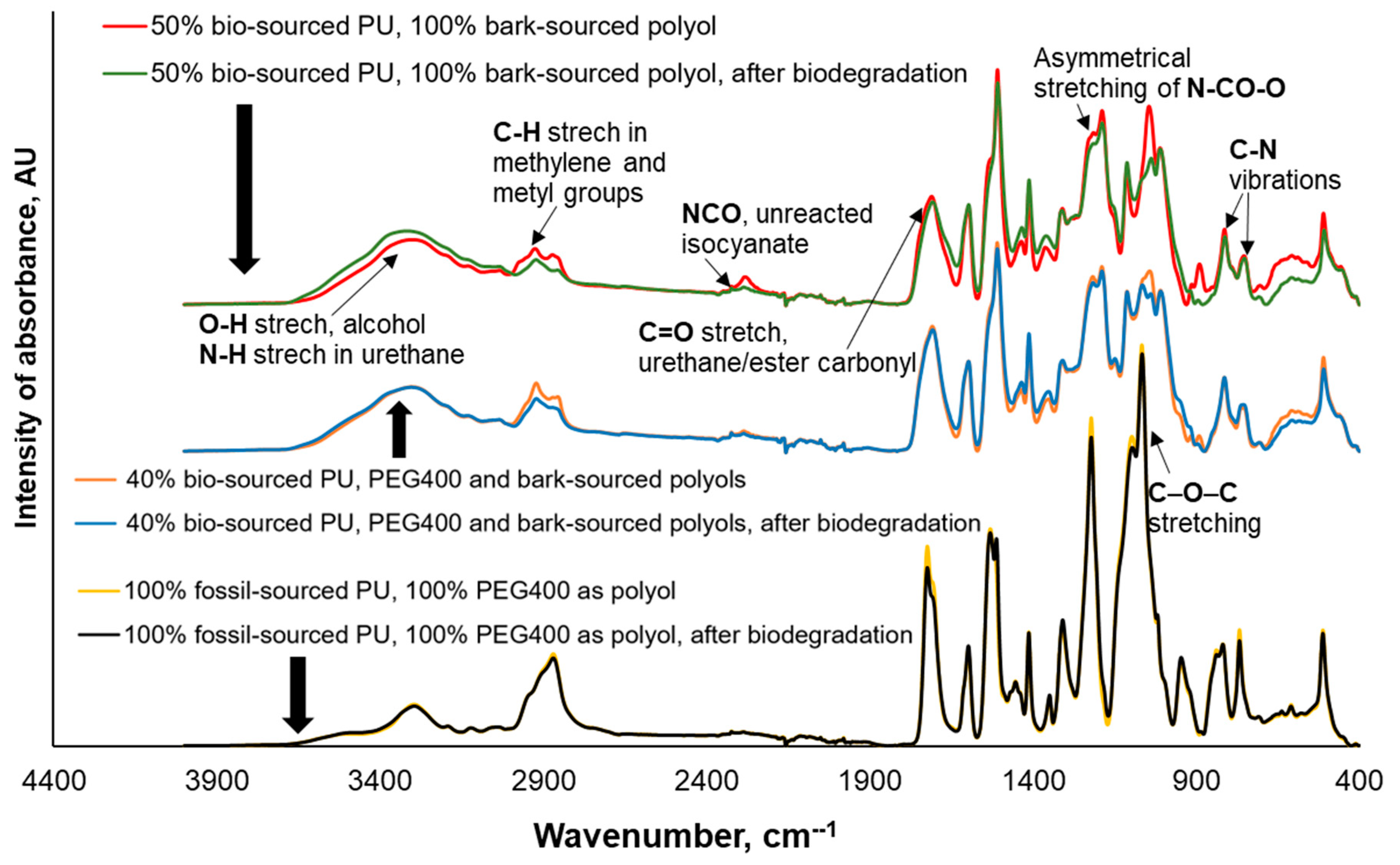

FTIR spectroscopy confirmed that the substitution of PEG400 with bark-sourced polyol as a building block significantly enhances the susceptibility of PU materials to biodegradation in soil. This is indicated by more prominent chemical changes in their structure, including decreased aliphatic C-H signals (2925-2869 cm

-1), C=O (urethane/ester carbonyl) signals (1725-1706 cm

-1), signals of asymmetrical stretching of N-CO-O (1220-1186 cm

-1), signals of C-O-C stretching (1065-1038 cm

-1), and signals corresponding to several C-N(C) vibrations (820-811 cm

-1), among others. Additionally, there is an increase in N–H and O-H stretching signals (3321-3296 cm

−1) (

Figure 3).

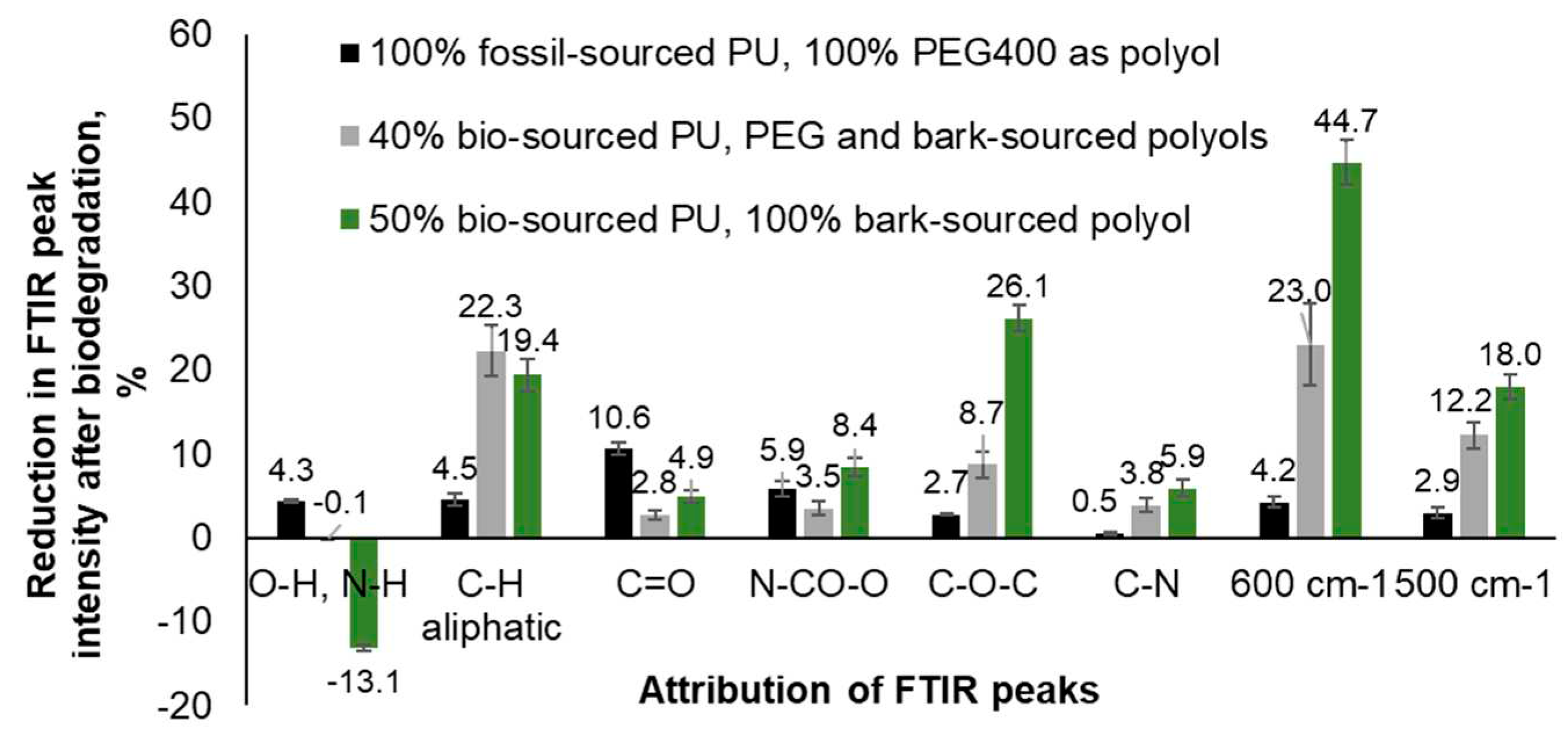

A decrease in the intensity of FTIR peaks corresponding to the vibration of various functional groups in the polyurethane network caused by biological degradation of material was expressed as a percentage of the peak intensity before biodegradation (

Figure 4). For the conventional polyether PU synthesized with PEG400 as polyol, this decrease varied in the range of 0.5-10.6% being the highest for C=O (urethane/ester carbonyl) signals (1725-1706 cm

-1). For the 40% and 50% bio-sourced PU with PEG400 partially and fully substituted by bark-derived biopolyol, it varied in the ranges of 2.8-27.0% and 4.9-44.7% correspondingly being the highest for peak at 600 cm

-1. Thus, the decrease of intensity of all peaks in FTIR spectra is much higher in the case of PU synthesized with bark-based polyol, replacing conventional PEG400 polyol. The only exception is the peak corresponding to the stretching of carbonyls in urethane ester groups. This can be explained by the presence of carbonyl groups in phenolic bark extractives, such as oregonin, whose adsorption overlaps with the adsorption of urethane carbonyls (

Figure 4).

The substitution of PEG400 with a polyol derived from bark in polyurethane (PU) formulations leads to an increase in the intensity of FTIR peaks associated with the stretching of O-H and N-H bonds following material biodegradation (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This augmentation in PU samples is commonly linked to the hydrolysis of ester bonds, or both ester and urethane bonds, as supported by previous research on polyester PUs (Oprea, 2010; Spontón et al., 2013). The presence of a significant negative correlation between the changes in intensity of FTIR peaks corresponding to O-H and N-H stretching, and the changes in intensity of peaks corresponding to N-CO-O, C-O-C, and C-N vibrations after PU biodegradation (

Table 2), confirms the generation of hydroxyl or/and amino groups through the hydrolysis of various chemical bonds within the polyurethane network. Since no increase in the intensity of FTIR peaks corresponding to O-H and N-H stretching was observed after biodegradation of polyether PU synthesized solely using PEG400 as a polyol, it can be concluded that the integration of bark extractives as building blocks promotes the hydrolysis of chemical bonds in PU structure.

The results of the non-isothermal thermogravimetric analysis of the polyurethane materials under study, performed in argon in the temperature range from 25°C to 700°C with a heating rate of 5°C per minute, confirmed the increased susceptibility to biodegradation of polyurethanes containing bark-sourced building blocks. This was evidenced by the residual mass of the material, which does not change after the biodegradation of 100% fossil-sourced PUs but increases by about 15% for bio-sourced polyurethanes. This increase can be explained by the removal of a fraction that gives a high yield of volatile products during the biological degradation of the materials.