Introduction

Measles is an acute infectious disease caused by the rubeola virus, and is one of the most contagious diseases. In a 100% susceptible population, a single measles case results in 12 to 18 secondary cases on average [

1]. Measles are spread by direct contact with droplets from the respiratory secretions of infected people and via the airborne route. Patients with measles are infectious from 4 days before to 4 days after their rash onset. The fact that the measles virus is contagious before the onset of recognizable symptoms can hinder quarantine measures’ efficacy, although isolation of susceptible contacts is recommended.

In South Korea, the measles-containing vaccine (MCV) became available in 1965 and the trivalent measles mumps rubella (MMR) vaccine was introduced in the early 1980s. Two doses of the MMR vaccine were implemented in 1997 [

2], with the first dose given at 12–15 months of age and the second dose given at 4–6 years of age

. In March 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) verified that measles was eliminated in South Korea, as a result of a high-quality case-based surveillance system and population immunity, which was achieved by a high vaccination rate (> 95.0% since 1996) [

3,

4].

The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) criteria for acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity against measles include at least one of the following: written documentation of the 2-dose MMR vaccination, laboratory evidence of immunity, laboratory confirmation of measles, or proof of birth before 1967 [

5]. Despite decades of vaccine use, measles imports and limited local or in-hospital transmission continue in South Korea [

6,

7,

8].

Here, we report a measles outbreak in a single hospital in South Korea, where an imported patient with typical measles transmitted the measles infection to two healthcare workers (HCWs), with presumptive evidence of measles immunity. In response, our hospital conducted a serological survey of measles in all HCWs and offered free MMR vaccines to seronegative HCWs. In addition, we have routinely performed measles antibody tests on newly hired HCWs since 2019. We also present measles seroprevalence data for HCWs stratified by birth year. This is to establish an infection control and prevention strategy for measles that is applicable to hospitals in countries with a measles-eliminated status.

Methods

Case Definition

Clinical measles virus infection was defined as fever and a typical maculopapular rash [

6]. Cases were confirmed by laboratory tests. A laboratory-confirmed case was defined as a clinical case patient with one or more of the following results: presence of measles immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody or measles-specific RNA in a nasopharyngeal swab.

Laboratory Testing

Serum specimens were tested for measles-specific IgM antibodies using an IgM capture enzyme immunoassay (EIA) as described previoiusly [

9]. Measles specific IgG was tested by enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for measles IgG (EUROIMMUN, Lübeck, Germany) and test results were interpreted according to manufacturer’s instructions

. IgM/IgG index ratios were derived by dividing the net absorbance values measured for IgM by those for IgG [

10]. The IgM/IgG ratios were compared as a measure of primary vs. secondary immune responses to infection. Index ratios > 1 suggested a primary immune response to measles, whereas ratios < 1 indicated a secondary response [

10].

Nasopharyngeal swabs were sent to public health laboratories for PCR. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and genotyping were performed.

Genotype Identification and Genetic Analysis

Viral RNA was extracted from throat swab samples or infected cell supernatants using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The highly variable 450-nucleotide (nt) region in the carboxy-terminus of the nucleocapsid protein (N-450) was amplified and sequenced for genotyping using forward (MeV216:5′-TGGAGCTATGCCATGGGAGT-3′) and reverse (MeV214:5′-TAACAATGATGGAGGGTAGG-3′) primers. RT-PCR was performed using a OneStep RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The amplification conditions were as follows: 50 °C for 30 min, followed by 95 °C for 15 min, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final 10-min extension at 72 °C.

Results

Outbreak Presentation

A 41-year-old man with fever, cough, and rash visited the emergency department of another hospital on May 17th, 2018 (Case 1). He lived in China, where there was a measles outbreak at the time [

11]. When his symptoms did not improve, he visited the emergency room (ER) of our hospital. The patient had conjunctivitis, pharyngeal injection, and a maculopapular rash that started on his face and spread to his chest 2 days after fever onset. The primary doctor initially diagnosed the patient with viral exanthema and placed him on ER Ward 1. However, after a medical examination by a senior doctor, the patient was clinically diagnosed with measles. He was sent to an isolation room in the ER after spending 4 h on Ward 1. He was admitted to an isolation room on the general ward, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results were reported as measles virus-positive 7 days after admission. Measles IgM and IgG were positive and borderline, respectively.

The ER has three wards and two isolation rooms. The three wards were adjacent and separated by a full-height wall. However, each ward did not have a door. Each ward has eight beds separated by curtains.

The infection control team performed contact tracing based on exposure and immune status [

12]. Initially, contacts were identified as those who had face-to-face contact or spent at least 15 min on Ward 1 with the index case. In total, there were 30 exposed patients and 5 exposed HCWs. All HCWs were considered measles immune due to their 2-dose MMR vaccination documentation, and there were no susceptible high-risk contacts among the 30 exposed patients.

Eleven days after the index patient visited the ER, an ER HCW developed a mild fever. Three days later, a rash appeared on her face that spread to her trunk. While this HCW had no prodromal symptoms, such as cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis both PCR, and measles IgM and IgG serology produced positive results (Case 2). The HCW had a record of the 2-dose MMR vaccination. In addition, the HCW was not initially identified as having contact with the index case. Further investigation showed that the HCW had no face-to-face contact and was not on Ward 1 for more than 15 min; however, the HCW worked in the ER at the same time for 4 hours. Case 2 was considered infectious 4 days before the rash onset. There were 158 exposures in HCWs and 206 exposures in patients. After Case 2, the definition of contact was modified. Contacts were considered all patients and HCWs who stayed in the ER, not just Ward 1, from the time the index patient had entered the ER to an additional two hours after he exited the ER. The exposed HCWs had their immunity against measles checked, including their 2-dose MMR vaccination status and birth year. When the evidence was unclear, the exposed HCWs received the MMR vaccination. However, after Case 2 occurred, we should have evaluated measles IgG in the ER’s HCWs, regardless of birth year (age).

Another HCW in the ER, born in 1967, developed two macular rashes on the neck 17 days after exposure to the index patient (Case 3). This patient also did not exhibit any prodromal symptoms. The patient was a nursing assistant who was not involved in the treatment of the index case. Although Case 3 was not on Ward 1 for more than 15 min, she worked in the ER for 4 h with the index case present. A nasopharyngeal swab for PCR was performed, but an IgG/IgM test was not performed because her symptoms were atypical. However, the HCW PCR results came back positive for the measles virus, resulting in 135 HCWs being exposed and 316 patients.

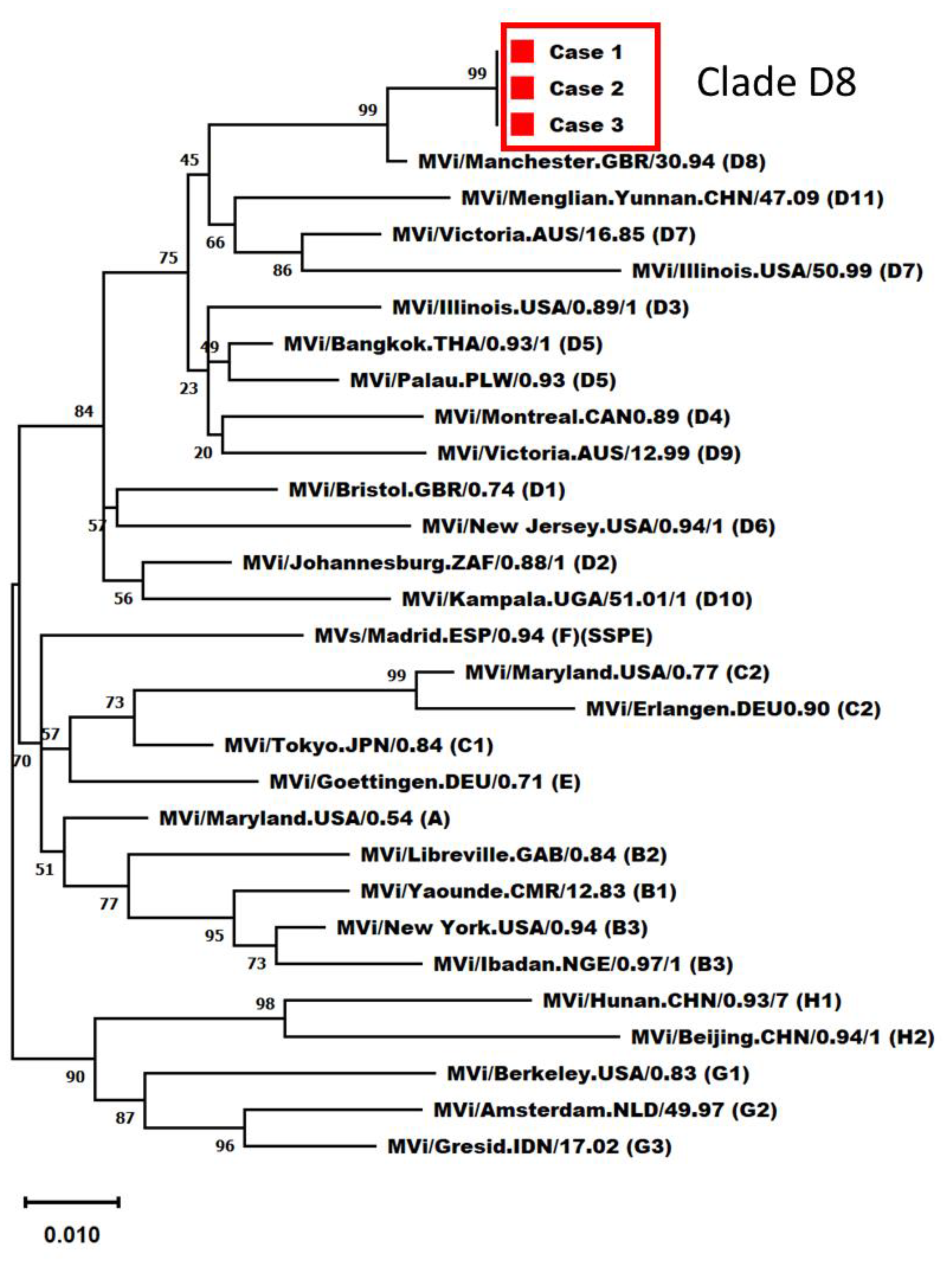

We performed phylogeographic analysis and found that the genotype of the measles virus in all three cases was D8, which circulates in China (

Figure 1). This outbreak resulted in 964 cases, with 341 HCWs and 623 ER patients. The hospital infection control team held an urgent meeting with the ER and local public health control department to coordinate further actions. We compiled a list of exposed HCWs and admitted patients, and implemented measures to prevent further infection. The measles IgG test was performed on all HCWs who entered and exited the ER, regardless of measles exposure or MMR vaccination status. Among the 341 HCWs, 68 were seronegative for measles IgG. Thirty-five were considered contacts and received an MMR vaccination. They were quarantined for three weeks after the last exposure. The other 33 received an MMR vaccination but were not quarantined. Local public health authorities contacted patients discharged from the hospital after exposure to measles in the ER, monitored them for symptoms, and administered vaccinations within 72 hours. The hospital infection control team has established a special isolated outpatient clinic for patients with measles. In the following week, two suspected measles cases among the contacts visited an isolated outpatient clinic. Both individuals had been ER inpatients when Cases 2 and 3 were admitted and infectious. Both nasopharyngeal swabs tested positive for measles RNA; however, the virus was shown to belong to the A genotype, which is a vaccine strain. No additional cases were observed among the 964 contacts of secondary patients.

Seroprevalence of Measles in All HCWs

Following the measles outbreak, our hospital has implemented routine measles antibody testing for newly hired HCWs since 2019, regardless of birth year or MMR vaccination status. Those who tested negative were vaccinated. Including HCWs tested at the time of the outbreak, 2,310 HCWs underwent measles IgG testing.

Table 1 shows the seroprevalence data for measles for HCWs stratified by year of employment.

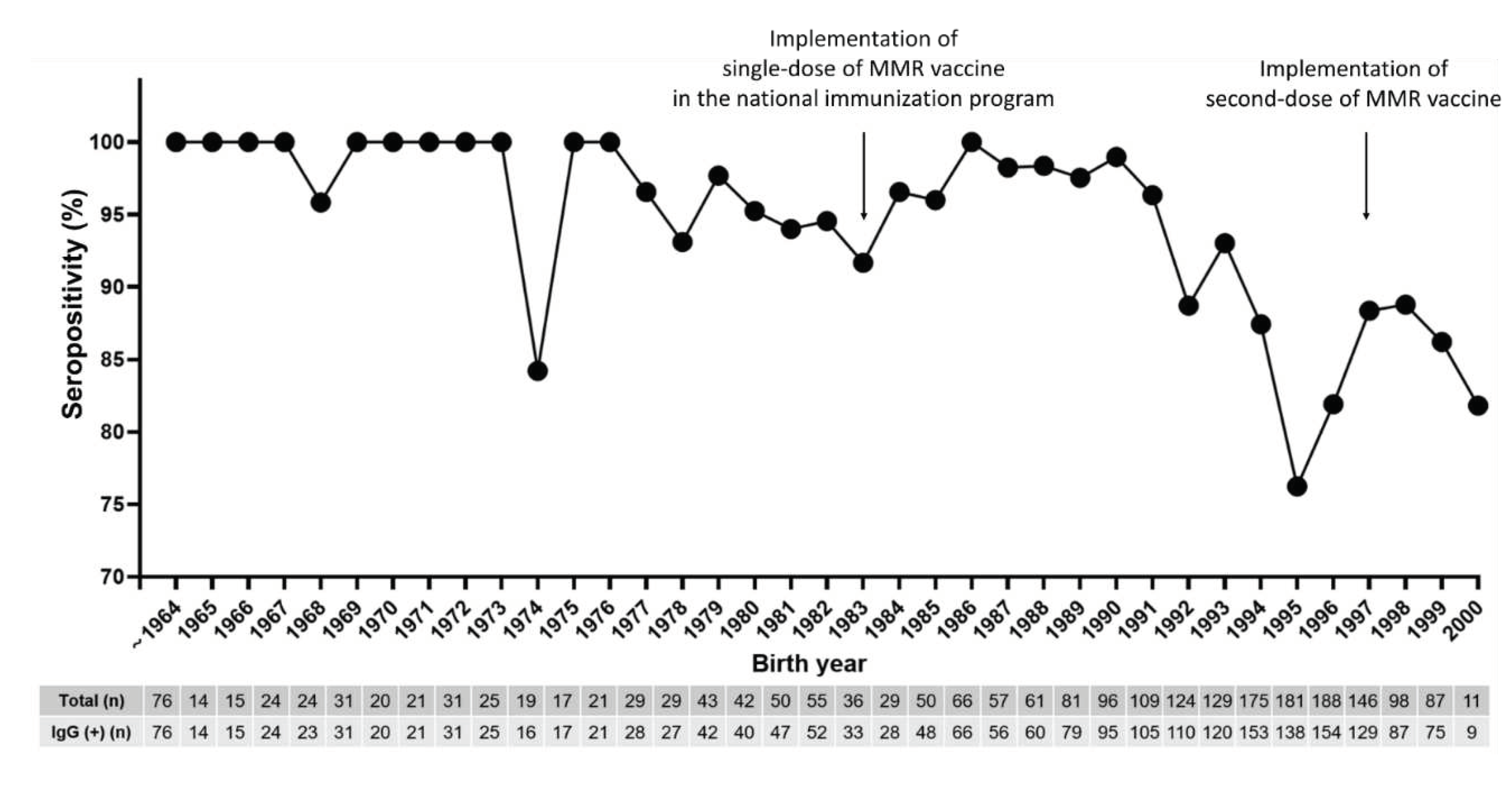

Figure 2 shows the seroprevalence data stratified by birth year.

The average age of those tested was 32.6 years, and 74.3% were female. The overall measles seropositivity was 88.9% (95% confidence interval, 87.5–90.1). HCWs born before 1967 had 100.0% seropositivity, indicating full herd immunity. However, HCWs born in 1974 had a lower seropositivity of 84.2% (16/19), suggesting that age alone cannot reliably determine immunity, even though this interpretation is limited by a small number. Among the 195 seronegative cases, 89.3% (175/195) HCWs were born after 1985, despite the presumption that birth cohorts between 1985 and 1994 had received the measles-rubella (MR) catch-up vaccination in 2001 [

13]. Notably, the birth cohort between 1994 and 1996 had a substantially low seropositivity for measles, thus signifying pockets of under-immunity. The measles vaccine was administered to HCWs who tested negative or equivocally negative for IgG antibodies.

Discussion

Following the outbreak, we made significant changes to our measles infection control policies. First, we developed a procedure for immediately isolating and testing patients suspected of measles and reporting them to the infection control office. Second, we conducted measles IgG tests for all HCWs, including those with administrative roles, regardless of their MMR vaccination status or birth year. Third, we now perform measles IgG tests on new HCWs regardless of their MMR vaccination status and age. In addition, we offer the MMR vaccine to those with negative test results.

To prevent nosocomial transmission, outpatient triage and in-hospital isolation with airborne transmission precautions should be applied to patients with suspected measles before confirming the diagnosis. Therefore, early suspicion and recognition are crucial for preventing widespread exposure. However, measles has been eliminated and is not endemic in South Korea [

3] and young doctors may lack familiarity with the clinical manifestations of measles due to limited local transmission. During this outbreak, the index case exhibited typical symptoms, whereas Cases 2 and 3 exhibited mild and atypical symptoms. Patients with a measles infection in high-vaccination-rate countries may present with modified measles, posing a challenge for early diagnosis [

14]. We addressed this issue by educating medical residents on atypical or modified measles presentations and isolating patients with suspected measles immediately.

Failure to initially identify Cases 2 and 3 as contacts of Case 1 led to delayed recognition of the disease. Accurate identification of all contacts, including transient or brief contacts, is crucial to avoid such delays and ensure timely prophylaxis. HCWs are at high risk of transmitting measles to vulnerable groups; however, identifying all HCWs can be challenging because of the multiple brief and undocumented encounters.

Documented administration of the 2-dose MMR vaccine is generally considered evidence of measles immunity; however, caution should be exercised, especially in young Korean HCWs. Seropositivity for measles gradually decreases over time after the 2nd dose of the MMR vaccine in the Korean population, as reported by Kang et al. [

15]. Birth cohorts after 1994 in South Korea received routine second doses of the MMR vaccine with a 95% coverage rate by submitting vaccination certificates before entering elementary school, but have the lowest measles seropositivity at about 40%. Kim et al. reported similar results among HCWs; the 1994 birth cohort in their hospital had the lowest antibody titers (approximately 30%), followed by the earlier cohort [

16]. In our study results, routine measles antibody testing for newly hired HCWs over several years revealed that 11.1% of all tested individuals were susceptible to measles. Among them, 89.3% were born after 1985 and were expected to have received a 2-dose MMR vaccine through national and catch-up vaccination programs. The seropositivity of HCWs born after 1994 was as low as 84.1% (745/886), and in particular, the seropositivity of HCWs born in 1995 was the lowest at 76.2% (138/181). Case 2, born in 1995, received a 2-dose MMR vaccine and tested positive for measles IgG at the onset of the rash. Previous studies on measles outbreaks in highly vaccinated populations have suggested potential factors for vaccine failure, such as waning immunity [

17,

18,

19]. Measles avidity assays may provide useful information for assessing the occurrence of measles in highly vaccinated populations [

20,

21].

The factors underlying the discrepancy between the low and high seropositive rates of the two-dose vaccination remain unclear. One potential explanation could be primary vaccine failure (failure to seroconvert after vaccination), which was considered less significant because primary vaccine failure was deemed less significant in the two-dose vaccination strategy era. Secondary vaccine failure (waning immunity after seroconversion) following a two-dose vaccination is a probable cause. In South Korea, administering the first vaccine dose at 12 months of age is common, and factors such as interference with maternal antibodies and an immature immune response to the initial dose may contribute to waning immunity in individuals relying solely on vaccine-induced protection without natural exposure to measles [

22,

23].

Age alone does not ensure immunity against measles in healthcare settings. In the United States, most people born before 1967 are presumed immune due to natural infection [

24]. In Korea, the 30–34 age group showed 95.4% antibody positivity in a 2002 immunity survey [

25], while the 1965–1974 birth cohort had 97% measles immunity in 2014 [

15,

26]. Thus, being born before 1967 is considered presumptive evidence of measles immunity in Korea. Although the measles IgG status of Case 3 was not confirmed, her atypical presentation suggested partial immunity. The KCDC's 2012 adult immunization guidelines recommended measles vaccination for medical personnel born after 1967 without evidence of immunity [

27]. However, owing to frequent measles outbreaks in healthcare facilities, the guidelines were revised in May 2019 to advise two doses of MMR vaccination for those at risk of contact with patients with measles or working in high-risk medical institutions without evidence of immunity [

27].

Fortunately, all the patients with measles recovered without complications, and despite over 900 identified exposures, no additional cases were found. While we did not assess the baseline immune status of Cases 2 and 3 against measles, our findings align with those of other studies, indicating that documented cases of secondary vaccine failure are unlikely to transmit the virus [

20,

21]. It is possible that the neutralizing antibody levels declined enough in secondary patients to permit symptomatic infection, but a robust memory response upon re-exposure likely shortened their infectious period. Therefore, it can be inferred that both HCWs were partially immune to measles.

This observation emphasizes the significance of identifying the prevalence of measles susceptibility among newly hired HCWs, regardless of age, to guide hospital-wide vaccination policies to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases. Young Korean HCWs should receive the highest priority for enhancing herd immunity in hospitals.

Our study had certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although Case 2 tested positive for measles IgG during diagnosis, we were unable to confirm secondary vaccine failure due to the lack of measles IgG avidity testing, such as plaque reduction-neutralization (PRN) tests. Additionally, measles serology was not performed in Case 3. As a result, we could not determine the immune status baseline of Cases 2 and 3 before measles infection. Second, the National Immunization Registry Information System, launched in 2000, was not widely used until 2011; therefore, MCV immunization records may not be complete for some HCWs. Lastly, this was a single-center study, and the seropositivity of young HCWs was relatively high compared with other studies in Korea. However, this study provides valuable seroepidemiological data for establishing hospital vaccination policies owing to the large cohort of HCWs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite high MMR vaccination rates in Korea, measles importation and limited local transmission continue to occur. Once the WHO lifts the international public health emergency for COVID-19, measles imports and outbreaks are expected to increase. In healthcare facilities, outbreaks of measles can have serious consequences because there are usually a large number of patients and HCWs exposed to it, particularly immunocompromised patients. To limit the spread of measles, early diagnosis and immediate isolation procedures, as well as the furloughing of potentially exposed HCWs who develop symptoms, remain key interventions. This study highlights the importance of assessing the prevalence of measles susceptibility among HCWs in healthcare settings, regardless of their vaccination status and age. This information is critical for policymaking regarding hospital-wide vaccinations to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases. Further studies are necessary to determine the most cost-effective vaccination strategies for the different HCW age groups in South Korea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Sungim Choi, Jae-Woo Chung, and Seong Yeon ParkData curation: Sungim Choi, Jae-Woo Chung, Yun Jung Chang, Eun Jung Lim, Sun Hee Moon, Han Ho Do, Jeong Hun Lee, Sung-Min Cho, Bum Sun Kwon and Seong Yeon Park. Formal analysis: Sungim Choi, and Seong Yeon Park. Investigation: Sungim Choi, Jae-Woo Chung, Yun Jung Chang, Eun Jung Lim, Sun Hee Moon, Han Ho Do, Jeong Hun Lee, Sung-Min Cho, Bum Sun Kwon and Seong Yeon Park. Methodology: Sungim Choi, and Seong Yeon Park. Resources: Sungim Choi, Jae-Woo Chung, Yun Jung Chang, Eun Jung Lim, Sun Hee Moon, Han Ho Do, Jeong Hun Lee, Sung-Min Cho, Bum Sun Kwon, Yoon-Seok Chung, and Seong Yeon Park. Software: Sungim Choi, Yoon-Seok Chung, and Seong Yeon Park. Supervision: Jae-Woo Chung, Han Ho Do, Jeong Hun Lee, Sung-Min Cho, Bum Sun Kwon, Yoon-Seok Chung, and Seong Yeon Park. Validation: Sungim Choi, and Seong Yeon Park. Writing – original draft: Sungim Choi. Writing – review & editing: Yoon-Seok Chung, and Seong Yeon Park.

Funding

The authors have received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gay, N.J. The Theory of Measles Elimination: Implications for the Design of Elimination Strategies. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, S27–S35,. [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Bae, G.-R. Current status of measles in the Republic of Korea: an overview of case-based and seroepidemiological surveillance scheme. Korean J. Pediatr. 2012, 55, 455–461,. [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Jee, Y.; Oh, M.-D.; Lee, J.-K. Measles Elimination Activities in the Western Pacific Region: Experience from the Republic of Korea. J. Korean Med Sci. 2015, 30, S115–S121,. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.U.; Kim, J.W.; Eom, H.E.; Oh, H.-K.; Kim, E.S.; Kang, H.J.; Nam, J.-G.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.K.; et al. Resurgence of measles in a country of elimination: interim assessment and current control measures in the Republic of Korea in early 2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 33, 12–14,. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.B.; Park, S.H.; Yi, Y.; Ji, S.K.; Jang, S.H.; Park, M.H.; Lee, J.E.; Jeong, H.S.; Shin, S. Measles seroprevalence among healthcare workers in South Korea during the post-elimination period. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2517–2521,. [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Sniadack, D.H.; Jee, Y.; Go, U.-Y.; So, J.S.; Cho, H.; Bae, G.-R.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.; Yoon, H.S.; et al. Outbreak of Measles in the Republic of Korea, 2007: Importance of Nosocomial Transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, S483–S490,. [CrossRef]

- Eom, H.; Park, Y.; Kim, J.; Yang, J.-S.; Kang, H.; Kim, K.; Chun, B.C.; Park, O.; Hong, J.I. Occurrence of measles in a country with elimination status: Amplifying measles infection in hospitalized children due to imported virus. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0188957,. [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Park, Y.-J.; Kim, J.W.; Eom, H.E.; Park, O.; Oh, M.-D.; Lee, J.-K. An Outbreak of Measles in a University in Korea, 2014. J. Korean Med Sci. 2017, 32, 1876–1878,. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.B.; Erdman, D.D.; Heath, J.; Bellini, W.J. Baculovirus expression of the nucleoprotein gene of measles virus and utility of the recombinant protein in diagnostic enzyme immunoassays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 2874–2880,. [CrossRef]

- Erdman, D.D.; Heath, J.L.; Watson, J.C.; Markowitz, L.E.; Bellini, W.J. Immunoglobulin M antibody response to measles virus following primary and secondary vaccination and natural virus infection. J. Med Virol. 1993, 41, 44–48,. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Rodewald L, Hao L, Su Q, Zhang Y, Wen N, et al. Progress Toward Measles Elimination - China, January 2013-June 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(48):1112-6.

- Baxi, R.; Mytton, O.T.; Abid, M.; Maduma-Butshe, A.; Iyer, S.; Ephraim, A.; Brown, K.E.; O'Moore, . Outbreak report: nosocomial transmission of measles through an unvaccinated healthcare worker--implications for public health. J. Public Heal. 2013, 36, 375–381,. [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Eom, H.-E.; Cho, S.-I. Trend of measles, mumps, and rubella incidence following the measles-rubella catch up vaccination in the Republic of Korea, 2001. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 1528–1531, doi:10.1002/jmv.24808.

- Mizumoto, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Chowell, G. Transmission potential of modified measles during an outbreak, Japan, March‒May 2018. Wkly. releases (1997–2007) 2018, 23, 1800239,. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Han, Y.W.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, A.-R.; Kim, J.A.; Jung, H.-D.; Eom, H.E.; Park, O.; Kim, S.S. An increasing, potentially measles-susceptible population over time after vaccination in Korea. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4126–4132,. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-K, Park H-Y, Kim S-H. A third dose of measles vaccine is needed in young Korean health care workers. Vaccine 2018;36(27):3888-9.

- Paunio, M.; Hedman, K.; Davidkin, I.; Valle, M.; Heinonen, O.P.; Leinikki, P.; Salmi, A.; Peltola, H. Secondary measles vaccine failures identified by measurement of IgG avidity: high occurrence among teenagers vaccinated at a young age. Epidemiology Infect. 2000, 124, 263–271,. [CrossRef]

- Atrasheuskaya, A.; Kulak, M.; Neverov, A.; Rubin, S.; Ignatyev, G. Measles cases in highly vaccinated population of Novosibirsk, Russia, 2000–2005. Vaccine 2008, 26, 2111–2118,. [CrossRef]

- Seward, J.F.; Orenstein, W.A. Editorial Commentary: A Rare Event: A Measles Outbreak in a Population With High 2-Dose Measles Vaccine Coverage. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 403–405,. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, J.B.; Rota, J.S.; Hickman, C.J.; Sowers, S.B.; Mercader, S.; Rota, P.A.; Bellini, W.J.; Huang, A.J.; Doll, M.K.; Zucker, J.R.; et al. Outbreak of Measles Among Persons With Prior Evidence of Immunity, New York City, 2011. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1205–1210,. [CrossRef]

- Hahné, S.J.M.; Nic Lochlainn, L.M.; van Burgel, N.D.; Kerkhof, J.; Sane, J.; Yap, K.B.; van Binnendijk, R.S. Measles Outbreak Among Previously Immunized Healthcare Workers, the Netherlands, 2014. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1980–1986,. [CrossRef]

- Gans, H.A.; Arvin, A.M.; Galinus, J.; Logan, L.; DeHovitz, R.; Maldonado, Y. Deficiency of the Humoral Immune Response to Measles Vaccine in Infants Immunized at Age 6 Months. JAMA 1998, 280, 527–532,. [CrossRef]

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE. Global measles elimination. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006;4(12):900-8.

- Shefer A, Atkinson W, Friedman C, Kuhar DT, Mootrey G, Bialek SR, et al. Immunization of health-care personnel: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports 2011;60(7):1-45.

- Kim, S.-S.; Han, H.W.; Go, U.; Chung, H.W. Sero-epidemiology of measles and mumps in Korea: impact of the catch-up campaign on measles immunity. Vaccine 2004, 23, 290–297,. [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.Y.; Park, W.B.; Kim, N.J.; Choi, E.H.; Funk, S.; Oh, M.-D. Estimating contact-adjusted immunity levels against measles in South Korea and prospects for maintaining elimination status. Vaccine 2019, 38, 107–111,. [CrossRef]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Adult Immunization. 2nd ed. Cheongju, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).