1. Introduction

Clean cooking is associated with multiple benefits, most notably health benefits, convenience of cooking, liberated time for cooks, reduced expenditure, and reduced carbon emissions. Adoption of clean cooking is a key part of achieving SDG7 (Indicators 7.1.2). Some of the impacts of clean cooking more readily lend themselves towards measurement, such as energy consumption. Digitally enabled metering technology means that the consumption of modern fuels such as electricity and LPG can be monitored in real time. This means that carbon emissions reductions can be monitored accurately, giving greater confidence in carbon credits issued, e.g., the Gold Standard “Methodology For Metered & Measured Energy Cooking Devices”. There is emerging evidence that cooking with modern fuels can in some contexts be cheaper than cooking with traditional biomass fuels. While some studies on the cost of cooking with different fuels have been based on modelling, others are based on empirical data [

1]. The health impacts of household air pollution are well established [

2], although efforts to validate low cost means of monitoring direct improvements in pollution from clean cooking are ongoing.

The importance of assessing the wider socio-economic benefits associated with clean cooking is growing with interest in innovative mechanisms for financing these kinds of development outcomes. Development Impact Bonds, or Social Impact Bonds, for example, are gaining traction as a mechanism for attracting private sector investment into the development sector. Such bonds aim to shift the risk associated with achieving development outcomes from institutional donors onto private sector project implementers. Development outcomes of interest can be social, such as improved health. The World Bank issued Sustainable Development Bonds to the value of USD 41 billion in 2022 [

3].

This paper considers the wider, still more subjective impacts of choice of clean cooking fuels. When Cookpad announced a competition to study the role of home cooking in personal wellness, this provided an opportunity to explore issues of wellbeing as captured by the Gallup World Poll database. By combining the World Poll database with the WHO Household Energy Database, the study assesses links between cooking fuel choices (using national averages) and a number of wellbeing indices. In order to understand the relative importance of choice of cooking fuels in wellbeing, regression modelling is used to control for the effects of demographic variables available in the Gallup database.

2. Background to Clean Cooking and Wellbeing

There are many different strands of research and theory around the subject of wellbeing. Income related measures were traditional metrics for determining wellbeing, before advancements in the 1960s and 1970s introduced terms such as happiness, quality of life and life satisfaction [

4], which look beyond measures of economic and material progress. In the 1990s, development organisations such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) began actively considering quality of life with the Human Development Index, to look beyond measures such as GDP. Increasingly, improving wellbeing has become important in development research, policy-making and determining progress on global objectives, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), most notably on SDG3 (Health and Wellbeing) which contains a subjective well-being indicator [

5].

Ideas of subjective and objective well-being, and measures designed to assess individuals’ happiness or quality of life, borrow heavily from disciplines such as psychology and philosophy: “ideas found in modern well-being research, e.g. the fundamental distinction between subjective and objective, originate from traditional philosophical theories” [

6]. Subjective wellbeing indicates “wellbeing as described by self” compared to objective wellbeing, alluding to measures or dimensions of life, e.g. health status, level of education or GDP [

7]. These two broad conceptual approaches dominate the field of wellbeing research [

8].

This paper considers the relationship between wellbeing and choice of clean cooking fuels, which have been associated with a wide range of socio-economic benefits. Accordingly, first, we consider the literature linking cooking fuels and objectives measures of wellbeing. It is apparent in this literature, that there is a growing body of peer-reviewed work linking the effect of traditional polluting cooking fuels on negative health outcomes, particularly with regards to premature deaths due to household air pollution.

Data and analyses from several authors have built strong evidence of cardiorespiratory, paediatric, and maternal disease associated with using solid biomass for cooking [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], which has captured the attention of policy makers at both national and international level. There is also evidence that the negative effects are largely gendered, disproportionally impacting women and children, due to heightened exposure to cooking fumes, predominantly because of traditional gender roles [16, 17] including home cooking responsibility [

18]. Additionally, women are primarily responsible for solid fuel collection and bear associated time implications [

19]. Prevalence of poor health outcomes due to polluting fuels is also observed to be highest in low and middle-income countries, where use of solid biomass fuel for cooking is more widespread [

11].

Equally, there is a body of work that links clean cooking fuel use with positive health outcomes [

21,

22,

23]. Studies show adoption of clean cooking fuels to have potential benefits to not only health but progress towards climate goals and other related SDGs [

24]. There is also nascent research into the potential for clean cooking fuels to positively impact mental health [

25], as a counterpoint to the evolving evidence of the detrimental impact of outdoor air pollution [

26], household air pollution and cooking fuels on mental illness, such as depression [

27]. Beyond study demonstrating the negative impact of polluting cooking fuels use on health, other evolving study links solid biomass cooking fuels to heightened economic costs for households, because of illness and higher medical expenses [

28] and worse educational outcomes [

29].

Study of subjective wellbeing is a rapidly growing empirical science, especially over the past decades and often works to complement objective measures [

30]. Subjective wellbeing, despite being a broad construct, is defined by Diener et al. as a “person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of his of her life, as judged and reported by themselves“[

31]. Key subjective wellbeing indices are a mix of experienced well-being measures (Positive Experience, Negative Experience and Daily Experience) taking into account ranges of emotion at a specific moment in time, for instance that day, and evaluative well-being measures (Life Evaluation) that requires respondents to give an evaluation of a longer period of time, for instance their lifetime [

32].

There are few studies that look at cooking fuel use and subjective wellbeing: it is an emerging field of research. Ma et al [

33] use national data from the 2016 China Labor-force Dynamics Survey to explore household cooking fuel choices and individuals’ subjective well-being, using two variables: happiness (an experienced measure), and life satisfaction (an evaluative measure). The paper concludes that a clean cooking fuel transition can significantly improve well-being within certain regions.

A few other national level studies have focussed on subjective well-being and specific segments of the population, such as the elderly [

34], finding that the adoption of clean cooking fuels significantly enhances middle-aged and senior peoples’ subjective life satisfaction, or rural residents [

35] whose life satisfaction is found to negatively correlate with solid fuel use. LPG can also support dimensions of well-being, however fuel transitions are deemed complex, multi-dimensional and context dependent [

19]. These studies have tended to focus on national level data rather than multinational surveys such as The Gallup World Poll, a dataset used for this paper, which is a rich, global and large evidence base for data on subjective wellbeing [

36].

One of the key debates in subjective wellbeing literature concerns the relationship between increasing income and happiness. To a point, the relationship between these two shows a positive correlation, both nationally and internationally, though the limits to this are considered by the work of Easterlin, and the notion of the Easterlin paradox: “cross-sectionally (e.g. at a particular point in time), income and happiness are positively correlated. As countries become richer over time this relationship does not hold” [

6]. Despite this consideration the positive relationship between income growth and subjective wellbeing is well-established and wealth is important to control for and factor into analyses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Creating an Aggregated Dataset

The methodology is based on looking globally at countries with a spread of mix of cooking fuels and looking for linkages with a number of wellbeing indices. The approach is based on combining two datasets:

Gallup World Poll dataset (2018-2021) – measures attitudes and behaviours of people across the world;

WHO Household Energy Database – proportion of households using a range of fuels as their primary cooking fuel.

Each year the Gallup World Poll surveys people in more than 150 countries worldwide, representing more than 98% of the world’s adult population [

37]. The survey covers a comprehensive range of issues that are related to development indicators. Recent surveys include a number of questions relating to cooking behaviours, which have been added at the request of Cookpad. The dataset includes indices reflecting the six key elements of the methodology; law and order, food and shelter, institutions and infrastructure, good jobs, wellbeing, and brain gain. These elements are described as the currency of a life that matters. Twenty one indices are calculated, each being constructed from a number of constituent questions; nine indices fall under the wellbeing category. The analysis has used a dataset furnished by Cookpad, which covers a four-year period from 2018 to 2021.

The WHO Household Energy Database draws upon a range of nationally representative household survey data from WHO member states. It comprises data from over 170 countries, but these countries do not align completely with the countries covered by the Gallup dataset; the WHO database includes a higher proportion of low and middle-income countries. It provides data on the primary fuel used for cooking, so takes no account of fuel stacking; this means that the actual use of all fuels will be underrepresented. The analysis has used data on the proportion of the population in each country using each different fuel. Data is available from 1960 to 2020, only data corresponding to the years covered by both the Gallup and WHO dataset have been used. i.e., three years from 2018 to 2020.

The two datasets were combined as follows:

Three-year data (2018 to 2020) were extracted from the Gallup dataset, covering 148 countries;

Data on each of the wellbeing indices was aggregated to one value per year for each country by calculating the mean of individual indices in each country;

In the same way, mean values of demographic variables were calculated for each year for each country from the Gallup dataset;

The aggregated Gallup data and WHO were then merged to generate the data set analysed in this paper. Each record represents a single country for a given year.

The number of countries for which data is available from both the Gallup and WHO datasets is presented in

Table 1. This shows that in terms of low-income countries, the dataset is skewed towards African countries, and in terms of high-income countries, it is dominated by Europe. Note that the analysis explores relationships between choice of clean cooking fuels and wellbeing indices at the country level, i.e., all countries are weighted equally, irrespective of population size. A list of countries within each region is given in

Table A1.

3.2. Identifying Key Wellbeing Indices

The study is concerned with the nine composite indices relating to wellbeing described in

Table 2. Each of these indices is, in turn, calculated from a small number of constituent variables (see

Table A2).

The literature has highlighted a strong relationship between cooking and personal health, particularly as it relates to household air pollution. We would, therefore, expect to find a strong relationship between choice of clean cooking fuels and the Personal Health Index. Potential links between choice of clean cooking fuels and other indices are less intuitive. Other impacts associated with clean cooking include:

Time savings – not only time spent cooking, but also time spent collecting fuel, and preparing fuel e.g., chopping wood into stove sized pieces. There is only emerging evidence that women use liberated time for additional household chores, leisure, and income generating activities [

38];

Reduced deforestation and environmental impact – this may not be apparent to urban residents, given that biomass fuels (notably charcoal) are harvested from rural areas and transported into urban markets;

Aspiration to modern living – especially in the connected world of the internet and social media, people aspire to enjoying the benefits of economic and technological progress.

Reduced hazard - collecting woodfuel is physically demanding, back breaking work, involving risk of injury, and often placing women in danger of sexual abuse e.g. [

39]. Collecting heavy bags of charcoal or LPG cylinders can also cause physical injury in the absence of a delivery service.

Bearing these factors in mind, an inspection of the constituent questions presented in

Table A2 can help identify those indices likely to be most closely matched to choice of clean cooking fuels.

Financial Life Index. Although there is emerging evidence that cooking with clean fuels can be cheaper than biomass fuels, this is largely as a result of recent innovations in energy efficient electric cooking devices coupled with increasing biomass fuel prices. In earlier years, the use of clean cooking fuels has been associated with higher incomes. Therefore, we might expect choice of clean cooking fuels to be only weakly linked to the economic status of the household.

Local Economic Confidence Index. Similarly, there will be many more pressing issues than clean cooking fuels affecting the local economy, with the possible exception of rural areas experiencing acute deforestation.

Personal Health Index. As mentioned above, polluting cooking fuels have been linked to a number of health conditions including pain and chronic conditions, which are specifically covered by these questions. We would therefore, expect a strong link between choice of clean cooking and personal health.

Social Life Index. Liberated cooking time can be used to meet people, but can also be used for income generating activities, additional chores, leisure etc., so we might expect only a weak link between choice of clean cooking fuels and social life index.

Civic Engagement Index. As above, liberated cooking time could offer more opportunities to volunteer time. However, these questions are designed to assess commitment to the local community, which might be expected to be independent of the household’s choice of cooking fuels.

Life Evaluation Index. This is an overall assessment of life satisfaction. Responses will be based on a wide range of issues, but one of the central tenants of the study is that use of clean cooking fuels will have an impact on overall wellbeing, so this is a key index to explore.

Positive Experience Index. Cooking with polluting fuels is often portrayed as drudgery [

40], but there is also evidence that people take great pride in their cooking and can enjoy cooking for their family. It is not clear, therefore, that this index would be linked to choice of clean cooking fuels.

Negative Experience Index. Physical pain is clearly linked to cooking with biomass fuels, not only linked to collecting and managing fuel, but also as a result of the design of traditional cooking devices e.g. three stone fire. Any number of household responsibilities can be a source of worry and stress, and this includes preparing meals; a study on the impact of household fridges gives some interesting examples of links between food preparation and worry and stress [

41].

Daily Experience Index. The ten constituent questions are those used in both the Positive and Negative Experience indices. Links to those two indices might, therefore, be expected to reveal more interesting insights into the links between use of clean cooking and specific aspects of wellbeing.

A preliminary analysis of links between choice of clean cooking fuels and the nine indices is summarised in

Table 3. This confirms that neither of the economic related indices are strongly linked to choice of clean cooking fuels. The table also confirms that the Positive Experience index is not linked to choice of clean cooking fuels and correlation with the Daily Experience index, although significant, is weaker than correlation with the Negative Experience index.

On this basis, the detailed analysis has explored links between choice of clean cooking fuels and a reduced set of key indices:

Personal Health

Social Life

Civic Engagement

Life Evaluation

Negative Experience

3.3. Demographic Variables

It has been noted that factors other than choice of cooking fuels will also influence wellbeing, most obviously income. The Gallup dataset includes data on household income in local currency, which has been levelized by converting into international dollars, which reflects local purchasing power. This was compared with per capita GDP figures from the World Bank

(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD accessed on 12 April 2023) to give us confidence in the figures. Results show that, overall, there is a strong correlation between average household income at the country level (from the Gallup dataset) and per capita GDP (World Bank data) (r = .826, p < .001). However, it is interesting to note that while correlations are strong in more developed regions (e.g., Europe and Eastern Mediterranean), they are weaker in lower income regions, especially South-East Asia and Africa (

Table 4). This probably reflects the concentrated nature of wealth generation in low-income countries, meaning that wealth is less evenly distributed among citizens. This suggests that the Gallup income data are not only reliable but, as a closer representation of household income, are also likely to be better suited to the purposes of the analysis.

The limitations of income as a measure of poverty are well recognised and there exists a wealth of literature on methodologies that take a more holistic view of poverty; perhaps one of the mostly widely accepted is the Multi-dimensional Poverty Index (MPI), adopted by UNDP in 2010 [

42]. This proposes measures for quantifying three domains of poverty: health, education and living standards (which includes the use of polluting cooking fuels). This level of data is not captured by the Gallup World Poll survey, but it is assumed that the household and respondent demographics presented in

Table 5 are all linked in some way to socio-economic status and poverty. Multiple regression analysis has been used to control for these poverty related characteristics.

When creating multiple regression models, we have started with a maximum model including all of the demographic variables as predictor variables. We then simplify the model as much as possible by removing non-significant predictor variables and variables that have a zero slope, whilst retaining choice of clean cooking energy as a predictor variable. Statistical analysis and regression modelling was done using SPSS.

4. Clean Cooking Fuels and Wellbeing Indices

The WHO database contains data on the use of biomass, charcoal, coal, electricity, gas, and kerosene as primary cooking fuels. For the purposes of this study, only electricity and gas have been classified as clean cooking fuels. The distribution of choice of cooking fuels across global regions is presented in

Table 6 and shows that overall, the choices of primary cooking fuels across all countries globally are predominantly clean cooking fuels (

Table 6). Countries in Africa have the lowest proportion of their populations primarily using clean cooking fuels (18.8%) followed by South-East Asia (63.9%).

The correlation coefficients presented in

Table 7 show that all of the key wellbeing indices are linked to the choice of clean cooking fuels. This shows that countries in which a higher proportion of the population use clean cooking fuels tend to have better personal health, are more likely to be thriving (Life Evaluation index), and have stronger social networks; they also less likely to experience negative feelings and less likely to engage in altruistic acts. With the exception of civic engagement, each of these relationships appear to support the hypothesis that clean cooking fuels are linked to more positive wellbeing.

The table goes on to break down links between choice of individual fuels and each of the key wellbeing indices. Correlations of use of coal and kerosene with wellbeing indices are rarely significant because the use of these fuels is substantial in only a small number of countries e.g., coal in China, and kerosene in Spain, Indonesia, India. Among clean fuels, it is interesting to note that choice of electricity for cooking appears to correlate more closely with wellbeing indices than choice of gas. Choice of biomass and charcoal correlate equally with wellbeing indices, and are linked to more negative wellbeing.

5. Clean Cooking, Wellbeing and Other Demographic Variables

5.1. Demographic Variables

In the previous section, it has been shown that there are moderate to strong relationships between different wellbeing indices and choice of clean cooking fuels. It has already been recognised that other factors will influence wellbeing, most notably financial or poverty status. To further understand the influence of choice of clean fuels on different wellbeing indices, regression modelling has been used, controlling for the demographic variables listed in

Table 5. Correlation of demographic variables reveals how, at the level of country mean values, these variables relate to income (see

Table 8):

Age – countries with higher average age have higher incomes (r = .617, p < .001). Given that mean age of the Gallup sample in a given country represents overall age of the population, higher mean age reflects countries with higher life expectancy, which is a characteristics of higher status countries.

Education level – countries with higher levels of education have higher incomes (r = .665, p < .01).

Number of children in household – countries where households have more children (under 15) tend to have lower incomes (r = -.547, p < .001).

Number of adults in household – countries with larger household sizes tend to have lower incomes (r = -.350, p < .001).

Access to internet – countries with higher internet penetration have higher incomes (r = .665, p < .001).

Employment – countries with lower unemployment rates have higher incomes (r = -.259, p < .001).

urban/rural – countries with a higher proportion of their population living in rural areas have lower incomes (r = .447, p < .001).

5.2. Regression Analysis

Clean cooking fuels is influential in all of the key wellbeing indices with the exception of the high level overall quality of life index (Life evaluation index);

Personal health is the index that is most strongly influenced by choice of clean cooking fuels; it is the only model in which clean fuels is the dominant factor in the model (

Table 9);

Lower choice of clean cooking fuels reflects higher Negative experience index, particularly experiencing pain;

Personal health and Negative experience models are similar, sharing many of the same variables in the model.

6. Gender and Burden of Cooking

The Gallup survey asked respondents how often they cooked lunch and dinner in the previous week. Summing the number lunches and dinners cooked in a week gives an integer variable ranging from 0 to 14 meals/week. In order to explore implications of the burden of cooking, a new categorical variable was created (“Cookcat”) to assess if there is a difference between the wellbeing of people cooking intensively and that of those not cooking at all. Respondents who did not cook at all were defined as “non-cooks” (0 meals/week) and respondents who cooked at least 12 times in a week were defined as intensive “cooks”. Among the respondents in the Gallup dataset, 24% cooked intensively and 24% did not cook at all.

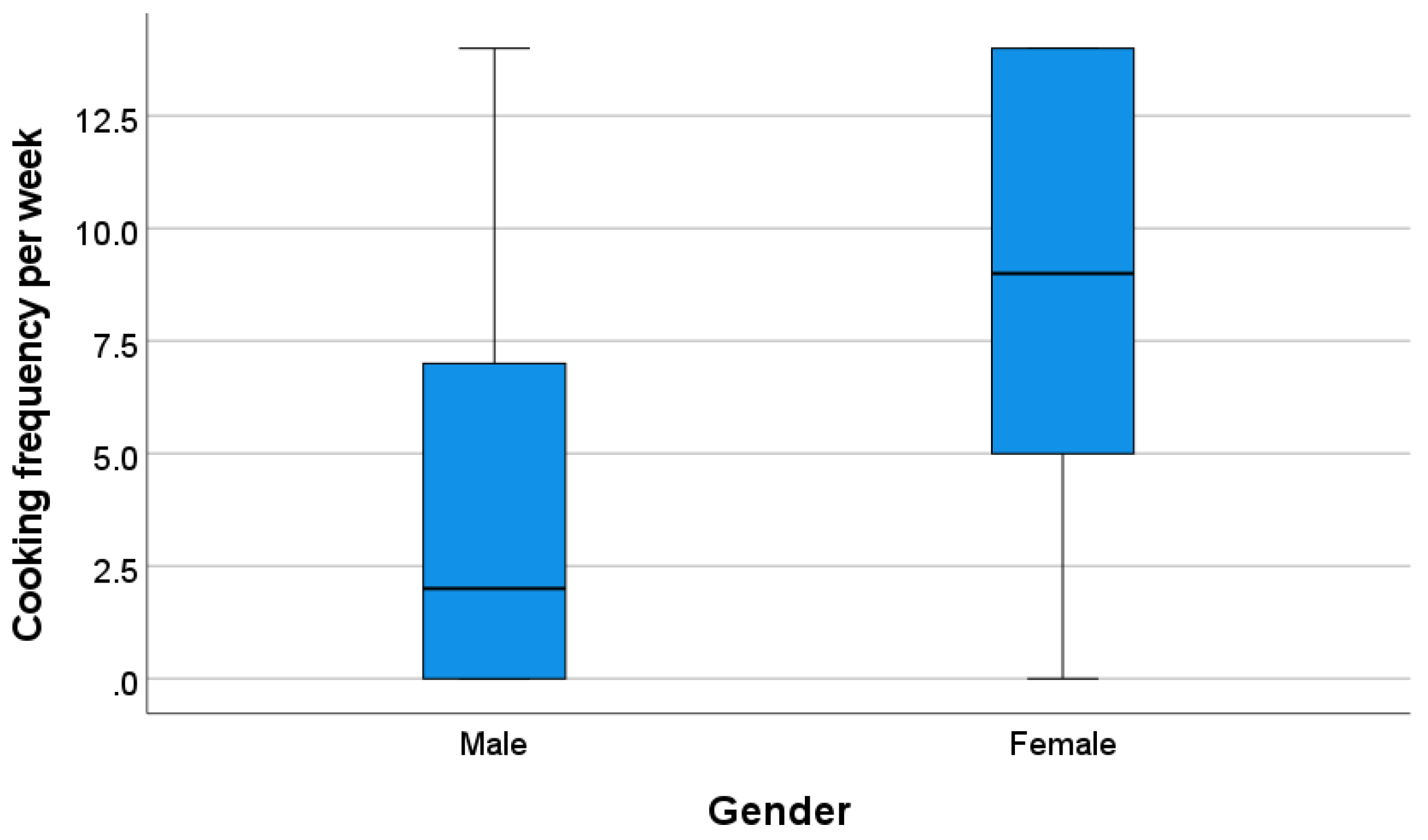

Data shows that cooking is a gendered activity globally.

Figure 1 shows that globally, on average, women cooked more than 4 times as much as men per week over the period 2018-2020. When comparing intensive cooks with non-cooks, women make up 79% of intensive cooks, but only 18% of the non-cooks.

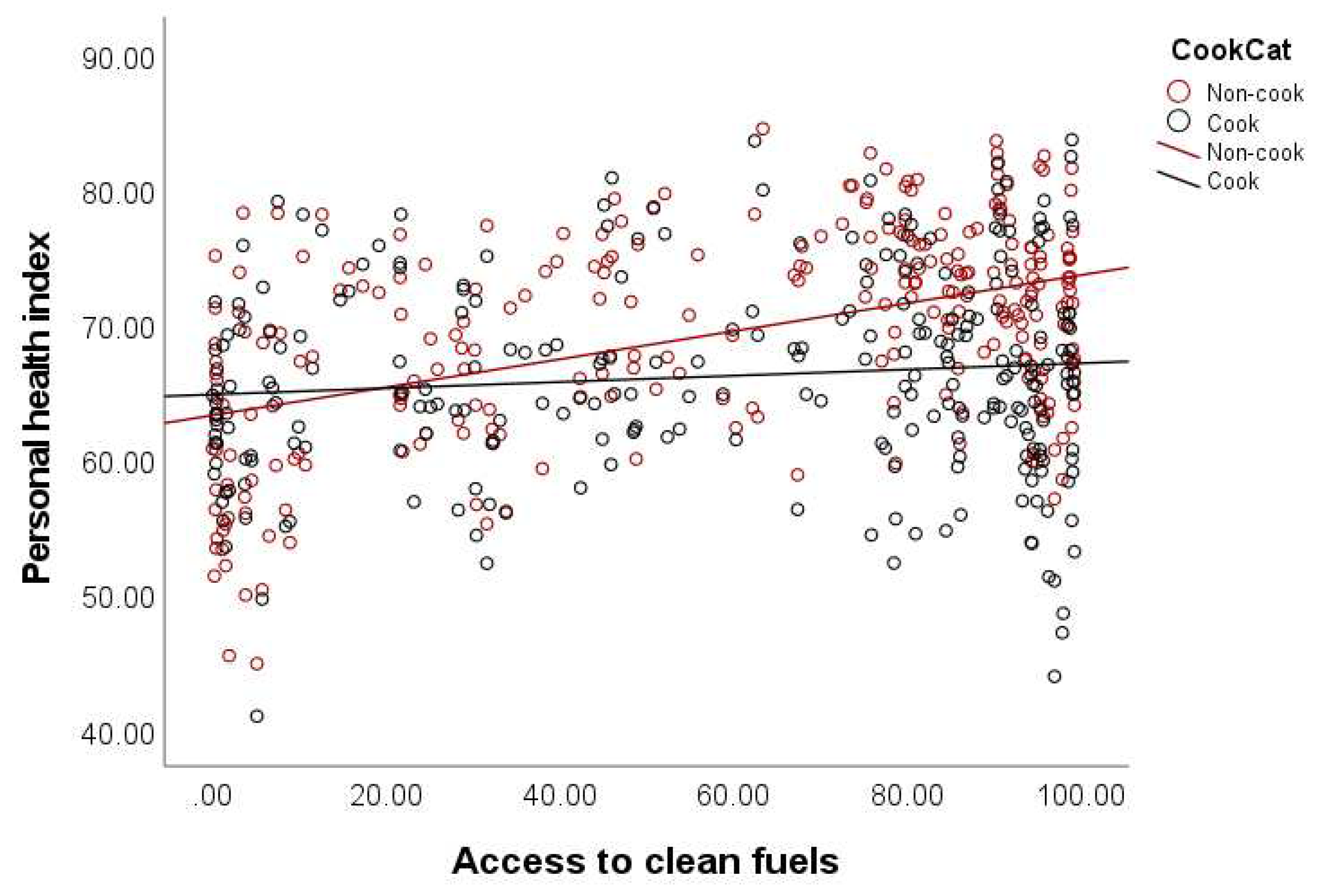

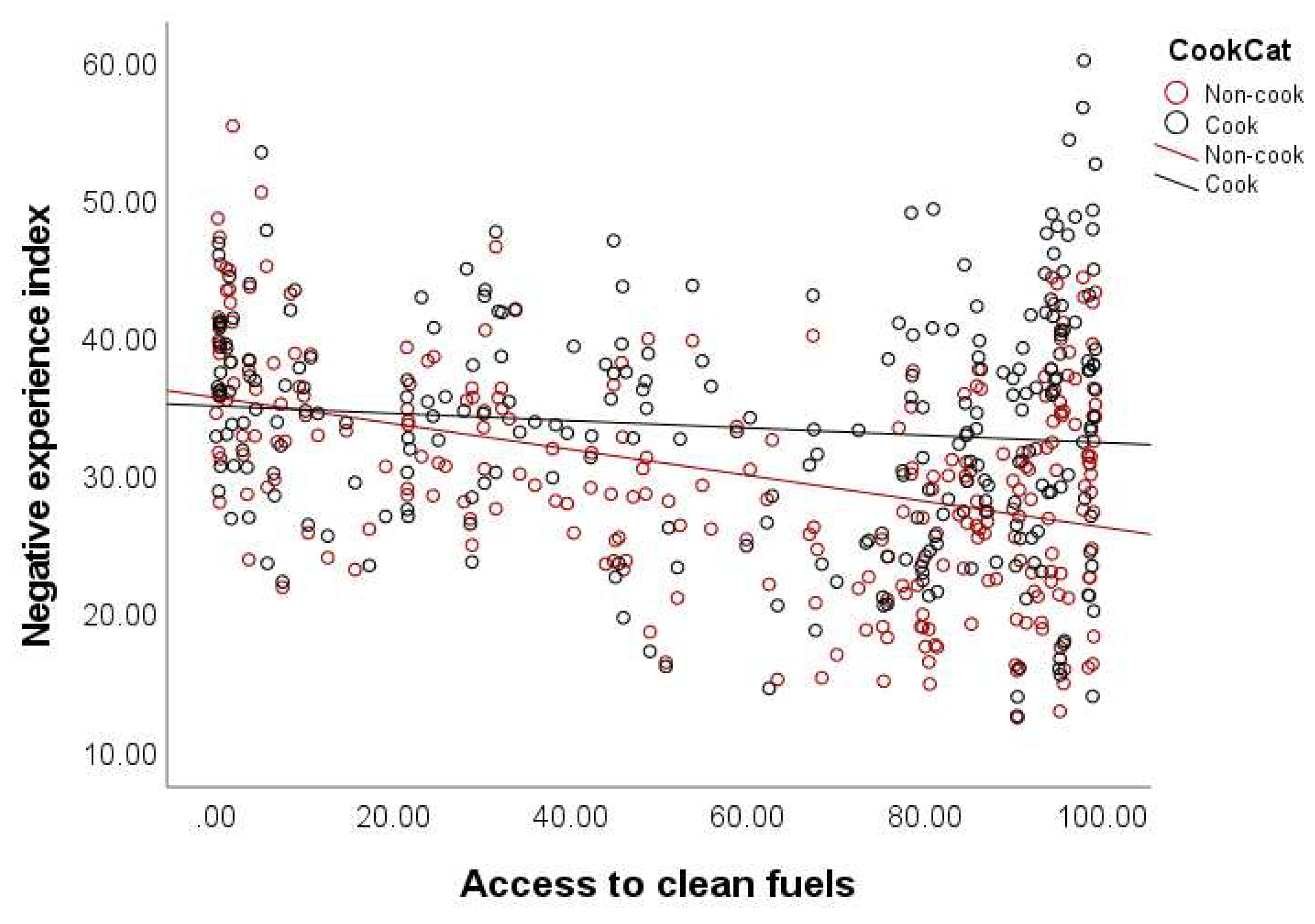

An expanded dataset has been created, comprising mean values of wellbeing indices at the country level for both intensive cooks and non-cooks, which have been merged with the country level variables on choice of cooking fuels. Average wellbeing figures from across all countries show that, overall, personal health and social life is weaker among intensive cooks, and negative experience is more negative among intensive cooks (

Table 14). This suggests that cooking intensively is associated with poorer wellbeing.

The question remains as to whether choice of cooking fuels contributes to the poorer wellbeing of intensive cooks.

Figure 2 shows how Personal health index varies with choice of clean cooking fuels for both groups. The interesting feature of this chart is that among countries predominantly using polluting fuels, there is little difference in the wellbeing index. However, the positive effect of increasing use of clean cooking fuels appears to be more acute among non-cooks. The same pattern can be seen for Negative experience index (

Figure 3). This is somewhat counterintuitive, as one might expect it to be cooks who would benefit most from the positive effects of clean cooking on wellbeing. This is an area for further investigation.

7. Clean Cooking and Electricity Access

Impressive progress has been made in improving access to electricity, with the number of people without electricity dropping from 1.2 billion in 2010 to 730 million in 2020 [

43]. This has been achieved with substantial investment, although this has recently been in decline from a peak of

$25 billion in 2017 [

43]. To achieve universal access to clean cooking by 2030 has been estimated to require still higher levels of investment (

$150 billion/year), yet there remains a huge disparity in investment in the electricity sector versus investment in clean cooking [

44].

Country level data on rates of access to electricity have been added to regression models as an additional predictor variable to assess the relative effect on wellbeing of gaining access to electricity and gaining access to clean cooking fuels. The percentage of population with access to electricity from Our World in data (OWID) dataset was used (

https://ourworldindata.org/energy-access accessed on 3 July 2023).

The revised regression models are presented in

Table 15,

Table 16,

Table 17,

Table 18,

Table 19. It should be noted that at the country level, electrification rates correlate closely with choice of clean cooking fuels (r = 0.812, p < 0.001). This is just about on the threshold of collinearity, which is regarded as between 0.8 and 0.9 [

45]. This makes it difficult for regression models to distinguish the relative importance of the two variables, and the model will tend to include one or other of the two.

Having said that, the tables show three types of relationships:

Choice of clean cooking fuels appears to be more influential than access to electricity - Negative experience and Civic engagement indices;

Choice of clean cooking fuels is of similar importance to electricity access - Personal health index;

Choice of clean cooking has not been included in the model – Life evaluation and Social life indices;

8. Discussion

In the description of wellbeing indices in

Section 3.2 it was asserted that both Personal Health index and Negative experience index would intuitively be linked to choice of cooking fuel. The regression analysis, controlling for demographic factors, confirms this to be the case. Furthermore, adding access to electricity as an additional predictor variable indicates that choice of clean cooking fuels is at least as important as access to electricity in predicting these two indicators of wellbeing. When compared with non-cooks, who are not directly exposed to cooking fuels, intensive cooks have poorer personal health and negative experience metrics. Given that women do much more cooking than men, this highlights gender implications of the burden of cooking.

The description of indices hypothesised that Social life index, which reflects personal relationships, would be only weakly linked to choice of cooking fuels, so it is interesting to find that it is significantly linked to choice of cooking fuels. This possibly reflects time savings associated with clean cooking fuels, giving people increased opportunities for social activities. On the other hand, it is not surprising to find that this index appears to be more closely linked to access to electricity than to choice of cooking fuels.

It is surprising to find that the Civil engagement index, which was expected to be independent, appears to be linked to choice of clean cooking fuels. The relationship is consistently negative, indicating that altruistic acts of volunteering are more common in countries with lower use of clean cooking fuels. We believe this reflects a difference in social norms between high and low income countries, rather than the effects of cooking fuel choices, but further research is needed to explore this.

Life evaluation was regarded as a key index because it is an important subjective measure of overall wellbeing, covering a range of unspecified issues. However, the analysis indicates that it is not directly linked to choice of cooking fuels.

The close correlation of choice of clean cooking fuels with electrification rates illustrates how countries with developed electrical infrastructure will also have effective gas distribution logistics, given that globally, gas is much more widely used than electricity for cooking.

The study has highlighted some areas for further research:

One might expect it to be cooks who would benefit most from the positive effects of clean cooking on wellbeing, but the increase in both Personal health and Negative experience indices with increasing use of clean cooking fuels is greater among non-cooks, which is counterintuitive.

The Civil engagement index, which was expected to be independent, appears to be linked to choice of clean cooking fuels.

Correlations indicated that choice of electricity as a cooking fuel is more closely linked to wellbeing than gas; links between specific fuels and wellbeing should be explored in more detail.

9. Conclusions

The study has combined Gallup data with primary cooking fuel use at the country level and shown that wellbeing is clearly linked to choice clean cooking fuels. Links have been explored using two approaches:

regression modelling of wellbeing indices as outcomes and using primary choice of cooking fuels (expressed as the proportion of populations using clean fuels) as a predictor variable, using country level averages;

comparing intensive cooks, who are exposed to cooking fuels, with non-cooks (using Gallup data).

Results from both approaches confirm that both the Personal heath and Negative experience indices are strongly linked to choice of clean cooking fuels. These findings are consistent with evidence found in the literature of links between clean cooking fuels and health and mental health, and between clean cooking fuels and wellbeing. The value of this study is in conferring external validity to the literature by taking a global, multi-country approach. The influence of cooking fuels does not appear to be strong enough to have an effect on overall wellbeing as assessed by the Life evaluation index.

The analysis highlights the potential for integrating eCooking into national electrification plans. Both the sustainability and the developmental benefit of increased access to electricity can be enhanced by linking to clean cooking, given that health outcomes (Personal health and Negative experience indices) appear to be as closely linked to choice of cooking fuels as to access to electricity.

Having demonstrated the links between cooking fuels and wellbeing, there is a case to be made for incorporating questions on choice of cooking fuels into the Gallup World Poll survey, which would complement the existing questions on frequency of cooking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. and J.L.; methodology, N.S., and J.N.; software, J.N., and N.S..; validation, N.S., and J.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S., J.N., and J.F.T.; writing—review and editing, N.S., J.N., and J.F.T.; visualization, J.N.; funding acquisition, N.S, J.L., and J.F.T.

Funding

This research was part funded by Cookpad and the Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS) programme (GB-GOV-1-300123).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cookpad for their support and funding for the study; also Gallup for providing access to the World Poll dataset. The authors also thank people who have contributed to the background research utilised.

Conflicts of Interest

The study was conducted independently of Cookpad; the authors had complete autonomy in the design, findings, and conclusions of the study. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of countries by region common to Gallup and WHO datasets.

Table A1.

List of countries by region common to Gallup and WHO datasets.

| Africa |

Europe |

Americas |

Eastern Mediterranean |

Western Pacific |

South-East Asia |

| Algeria |

Albania |

Argentina |

Afghanistan |

Cambodia |

Bangladesh |

| Benin |

Armenia |

Bolivia |

Egypt |

China |

India |

| Botswana |

Austria |

Brazil |

Iran |

Laos |

Indonesia |

| Burkina Faso |

Azerbaijan |

Chile |

Iraq |

Malaysia |

Myanmar |

| Burundi |

Belarus |

Colombia |

Jordan |

Mongolia |

Nepal |

| Cameroon |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Costa Rica |

Libya |

Philippines |

Sri Lanka |

| Chad |

Czech Republic |

Dominican Republic |

Morocco |

South Korea |

Thailand |

| Comoros |

Estonia |

Ecuador |

Pakistan |

Vietnam |

|

| Congo Brazzaville |

Georgia |

El Salvador |

Saudi Arabia |

|

|

| Eswatini |

Greece |

Guatemala |

Tunisia |

|

|

| Ethiopia |

Kazakhstan |

Haiti |

United Arab Emirates |

|

|

| Gabon |

Kyrgyzstan |

Honduras |

Yemen |

|

|

| Gambia |

Latvia |

Mexico |

|

|

|

| Ghana |

Moldova |

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

| Guinea |

Montenegro |

Panama |

|

|

|

| Ivory Coast |

Romania |

Paraguay |

|

|

|

| Kenya |

Russia |

Peru |

|

|

|

| Lesotho |

Serbia |

Uruguay |

|

|

|

| Liberia |

Slovakia |

Venezuela |

|

|

|

| Madagascar |

Slovenia |

|

|

|

|

| Malawi |

Spain |

|

|

|

|

| Mali |

Tajikistan |

|

|

|

|

| Mauritania |

Turkey |

|

|

|

|

| Mauritius |

Turkmenistan |

|

|

|

|

| Mozambique |

Ukraine |

|

|

|

|

| Namibia |

Uzbekistan |

|

|

|

|

| Niger |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nigeria |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rwanda |

|

|

|

|

|

| Senegal |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sierra Leone |

|

|

|

|

|

| South Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanzania |

|

|

|

|

|

| Togo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Uganda |

|

|

|

|

|

| Zambia |

|

|

|

|

|

| Zimbabwe |

|

|

|

|

|

Table A2.

Wellbeing indices constituent questions (Gallup dataset).

Table A2.

Wellbeing indices constituent questions (Gallup dataset).

| Financial Life Index |

Which one of these phrases comes closest to your own feelings about your household’s income these days: living comfortably on present income, getting by on present income, finding it difficult on present income, or finding it very difficult on present income? (WP2319) |

| |

Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your standard of living, all the things you can buy and do? (WP30) |

| |

Right now, do you feel your standard of living is getting better or getting worse? (WP31) |

| |

Right now, do you think that economic conditions in the city or area where you live, as a whole, are getting better or getting worse? (WP88) |

| Local Economic Confidence Index |

Right now, do you think that economic conditions in the city or area where you live, as a whole, are getting better or getting worse? (WP88) |

| |

How would you rate your economic conditions in this city today – as excellent, good, only fair, or poor? (WP19472) |

| Personal Health Index |

Do you have any health problems that prevent you from doing any of the things people your age normally can do?(WP23) |

| |

Now, please think about yesterday, from the morning until the end of the day. Think about where you were, what you were doing, who you were with, and how you felt. Did you feel well-rested yesterday?(WP60) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about physical pain? (WP68) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about worry?(WP69) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about sadness?(WP70) |

| Social Life Index |

If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not? (WP27) |

| |

In the city or area where you live, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the opportunities to meet people and make friends? (WP10248) |

| Civic Engagement Index |

Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about donated money to a charity? (WP108) |

| |

Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about volunteered your time to an organization? (WP109) |

| |

Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help? (WP110) |

| Life Evaluation Index |

Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time? (WP16) |

| |

Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. Just your best guess, on which step do you think you will stand in the future, say about five years from now? (WP18) |

| Positive Experience Index |

Did you feel well-rested yesterday? (WP60) |

| |

Were you treated with respect all day yesterday? (WP61) |

| |

Did you smile or laugh a lot yesterday? (WP63) |

| |

Did you learn or do something interesting yesterday? (WP65) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about enjoyment? (WP67) |

| Negative Experience Index |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about physical pain? (WP68) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about worry? (WP69) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about sadness? (WP70) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about stress? (WP71) |

| |

Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about anger? (WP74) |

| Daily Experience Index |

Positive Experience + Negative Experience |

References

- USAID Alternatives to Charcoal (A2C). Cost of Cooking Study. 2022.

- Rysankova D, Putti VR, Hyseni B, et al. Clean and Improved Cooking in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2015/08/18/090224b08307b414/4_0/Rendered/PDF/Clean0and0impr000a0landscape0report.pdf (2014).

- World Bank. Sustainable Development Bonds & Green Bonds 2022. https://issuu.com/jlim5/docs/world_bank_ibrd_impact_report_2021_web_ready_r01?fr=sYTBhOTM4NTM3MTk (2023).

- Allin, P.; Hand, D.J. New statistics for old?-measuring the wellbeing of the UK. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44682550 (2017).

- De Neve, J.E.; Sachs, J.D. The SDGs and human well-being: a global analysis of synergies, trade-offs, and regional differences. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drydyk, J.; Keleher, L. Routledge Handbook of Development Ethics; 2019.

- Teghe, D.; Rendell, K. Social wellbeing: a literature review. epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Western, M.; Tomaszewski, W. Subjective wellbeing, objective wellbeing and inequality in Australia. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, N.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Albalak, R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. 2000. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/268218 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Parikh, J. Hardships and health impacts on women due to traditional cooking fuels: A case study of Himachal Pradesh, India. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7587–7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken Lee, K.; Bing, R.; Kiang, J.; et al. Adverse health effects associated with household air pollution: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and burden estimation study. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7564377/. (2020).

- Malla, S.; Timilsina, G.R. Household Cooking Fuel Choice and Adoption of Improved Cookstoves in Developing Countries: A Review. 2014. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Peabody, J.W.; Riddell, T.J.; Smith, K.R.; et al. Indoor Air Pollution in Rural China: Cooking Fuels, Stoves, and Health Status. Arch Environ Occup Health 2005, 60, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki-Hyun, K.; Shamin, A.; Ehsanul, K. A review of diseases associated with household air pollution due to the use of biomass fuels. J Hazard Mater, 16 March 0304. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A.; Xue, J. Fuel for life: Domestic cooking fuels and women’s health in rural China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- James, B.S.; Shetty, R.S.; Kamath, A.; et al. Household cooking fuel use and its health effects among rural women in southern India-A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2020, 15, Epub. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silwal, A.R.; McKay, A. The Impact of Cooking with Firewood on Respiratory Health: Evidence from Indonesia. J Dev Stud 2015, 51, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 18. Wolfson JA, Ishikawa Y, Hosokawa C, et al. Gender differences in global estimates of cooking frequency prior to COVID-19. Appetite. [CrossRef]

- Malakar, Y.; Day, R. Differences in firewood users’ and LPG users’ perceived relationships between cooking fuels and women’s multidimensional well-being in rural India. Nat Energy 2020, 5, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 20. Floess E, Grieshop A, Puzzolo E, et al. Scaling up gas and electric cooking in low- and middle-income countries: climate threat or mitigation strategy with co-benefits? Environ Res Lett. [CrossRef]

- Capuno, J.J.; Tan, C.A.R.; Javier, X. Cooking and coughing: Estimating the effects of clean fuel for cooking on the respiratory health of children in the Philippines. Glob Public Health 2018, 13, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anenberg SC, Henze DK, Lacey F, et al. Air pollution-related health and climate benefits of clean cookstove programs in Mozambique. Environ Res Lett 2017, 12, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, P.; Sharma, A.; Mahal, A. Impact of cleaner fuel use and improved stoves on acute respiratory infections: Evidence from India. Int Health 2017, 9, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, J.; Quinn, A.; Grieshop, A.P.; et al. Clean cooking and the SDGs: Integrated analytical approaches to guide energy interventions for health and environment goals. Energy Sustain Dev 2018, 42, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Han, C.; Teng, M. Does clean cooking energy improve mental health? Evidence from China. Energy Policy. [CrossRef]

- King, J.D.; Zhang, S.; Cohen, A. Air pollution and mental health: associations, mechanisms and methods. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2022, 35, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Guo Y, Xiao J, et al. The effect of polluting cooking fuels on depression among older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Sci Total Environ 2022, 838, 155690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Wei, K. Does Use of Solid Cooking Fuels Increase Family Medical Expenses in China? Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Das, U. Adding fuel to human capital: Exploring the educational effects of cooking fuel choice from rural India. Energy Econ. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra: Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.; Oishi, S. Subjective Well-being: The Science of Happiness and Life Satisfaction; Snyder, C., Lopez, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610443258 (1999).

- Ma, W.; Vatsa, P.; Zheng, H. Cooking fuel choices and subjective well-being in rural China: Implications for a complete energy transition. Energy Policy. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, Q. The effect of cooking fuel choice on the elderly’s well-being: Evidence from two non-parametric methods. Energy Econ 2023, 125, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Will the use of solid fuels reduce the life satisfaction of rural residents—Evidence from China. Energy Sustain Dev 2022, 68, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapteyn, A.; Lee, J.; Tassot, C.; et al. Dimensions of Subjective Well-Being. Soc Indic Res 2015, 123, 625–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. Gallup Worldwide Researc Methodology and Codebook.

- Leary, J.; Scott, N.; Leach, M.; et al. Understanding the Impact of Electric Pressure Cookers (EPCs ) in East Africa: A Synthesis of Data from Burn Manufacturing’s Early Piloting. 2023.

- Njenga, M.; Gitau, J.K.; Mendum, R. Women’s work is never done: Lifting the gendered burden of firewood collection and household energy use in Kenya. Energy Res Soc Sci 2021, 77, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Burning opportunity: clean household energy for health, sustainable development, and wellbeing of women and children. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/9789241565233_eng.pdf (2016).

- Sanni, M.; Neureiter, K.; Raksit, A. How innovation in off-grid refrigeration impacts lives in Kenya. 2019.

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Acute Multidimensional Poverty: A New Index for Developing Countries. 2010.

- IEA; IRENA; UNSD; et al. Tracking SDG7: the Energy Progress Report. Washington D.C., 2022.

- (ESMAP) ESMAP. The State of Access to Modern Energy Cooking Services. Washigton D.C.: World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/937141600195758792/the-state-of-access-to-modern-energy-cooking-services (2020).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS; SAGE Publications: 2009.

Figure 1.

Mean cooking frequency by gender at global level (Gallup dataset).

Figure 1.

Mean cooking frequency by gender at global level (Gallup dataset).

Figure 2.

Relationship between Personal health index and choice of clean cooking fuels - intensive cooks v. non-cooks.

Figure 2.

Relationship between Personal health index and choice of clean cooking fuels - intensive cooks v. non-cooks.

Figure 3.

Relationship between Negative experience index and choice of clean cooking fuels - intensive cooks v. non-cooks.

Figure 3.

Relationship between Negative experience index and choice of clean cooking fuels - intensive cooks v. non-cooks.

Table 1.

Regional distribution of countries in aggregated dataset (number of countries in each region).

Table 1.

Regional distribution of countries in aggregated dataset (number of countries in each region).

| |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

Total |

| Global |

107 |

100 |

74 |

282 |

| Africa |

36 |

36 |

18 |

90 |

| Americas |

19 |

15 |

14 |

49 |

| Eastern Mediterranean |

11 |

11 |

9 |

31 |

| Europe |

26 |

24 |

21 |

71 |

| South-East Asia |

7 |

6 |

6 |

19 |

| Western Pacific |

8 |

8 |

6 |

22 |

Table 2.

Description of wellbeing indices.

Table 2.

Description of wellbeing indices.

| Index |

Measure |

Description |

| Life Evaluation Index |

1-3 |

A measure of respondents’ perceptions of where they stand now and in the future. |

| Social Life Index |

0-100 |

An assessment of respondent’s social support structure and opportunities to make friends |

| Financial Life Index |

0-100 |

A measure of respondents’ personal economic situations and the economics of the community where they live |

| Local Economic Confidence Index |

-100 to +100 |

An assessment of the economic conditions in respondents’ city today, and whether they think economic conditions in their city as a whole are getting better or worse. |

| Personal Health Index |

0-100 |

A measure of perceptions of one’s own health |

| Positive Experience Index |

0-100 |

A measure of respondents’ experienced well-being on the day before the survey |

| Negative Experience Index |

0-100 |

A measure of respondents’ experienced well-being on the day before the survey |

| Daily Experience Index |

0-100 |

A measure of respondents’ experienced well-being on the day before the survey |

| Civic Engagement Index |

0-100 |

An assessment of respondents’ inclination to volunteer their time and assistance to others. It is also a measure of respondent’s commitment to the community where he or she lives |

Table 3.

Correlation of indices with proportion of population using Clean Cooking Fuels (global).

Table 3.

Correlation of indices with proportion of population using Clean Cooking Fuels (global).

| Index |

Pearson’s r |

| Financial Life |

.182**

|

| Local Economic Confidence |

n/s |

| Personal Health |

.361***

|

| Social Life |

.376***

|

| Civic Engagement |

-.299***

|

| Life Evaluation |

.347***

|

| Positive Experience |

n/s |

| Negative Experience |

-.313***

|

| Daily Experience |

.248***

|

Table 4.

Relationship between Income per capita and GDP per capita, PPP.

Table 4.

Relationship between Income per capita and GDP per capita, PPP.

| Region |

Pearson’s r |

| World |

.826*** |

| Africa |

.611*** |

| Americas |

.514*** |

| Europe |

.884*** |

| South-East Asia |

.463* |

| Western Pacific |

.880*** |

| Eastern Mediterranean |

.938*** |

Table 5.

Household demographic variables in the Gallup dataset.

Table 5.

Household demographic variables in the Gallup dataset.

| Variable |

Coding |

| Income per capita |

Continuous (PPP USD) |

| Age |

Integer |

| Education level |

1 = completed elementary education or less (up to 8 years of basic education); 2 = Secondary education - three-year secondary education and some years beyond secondary education (9 to 15 years of education); 3 = completed 4 years of education beyond high school and/or received a 4-year college degree |

| Children under 15 |

Integer |

| Residents over 15 |

Integer |

| Access to internet |

1 = yes; 2 = no |

| Employment |

1 = unemployed; 2 = part-time employed (self-employed or working for an employer); 3 = Full-time employed ((self-employed or working for an employer) |

| Rural/urban |

1 = rural; 2 = urban |

Table 6.

Proportion of population with primary reliance on fuels for cooking, by fuel type.

Table 6.

Proportion of population with primary reliance on fuels for cooking, by fuel type.

| |

Africa |

Americas |

Eastern Mediterranean |

Europe |

South-East Asia |

Western Pacific |

Total |

| Biomass |

60.8% |

9.6% |

22.1% |

7.5% |

33.1% |

20.4% |

29.1% |

| Charcoal |

14.7% |

1.4% |

2.3% |

0.0% |

0.4% |

0.8% |

3.2% |

| Coal |

0.4% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.6% |

0.9% |

1.6% |

0.8% |

| Electricity |

6.4% |

2.5% |

1.0% |

15.9% |

1.2% |

28.9% |

10.4% |

| Gas |

12.4% |

84.4% |

70.3% |

65.7% |

62.7% |

45.3% |

52.9% |

| Kerosene |

3.0% |

0.1% |

0.5% |

3.4% |

0.5% |

0.1% |

1.0% |

| Clean fuels |

18.8% |

87.0% |

71.3% |

81.6% |

63.9% |

74.2% |

63.4% |

Table 7.

Wellbeing Indices – Relationships with proportion of population using different cooking fuels.

Table 7.

Wellbeing Indices – Relationships with proportion of population using different cooking fuels.

| |

Pearson’s r |

| Cooking Fuel |

Personal Health |

Life Evaluation |

Social Life |

Negative Experience |

Civic Engagement |

| Biomass |

-.373***

|

-.371***

|

-.360***

|

.292***

|

.227***

|

| Charcoal |

-.350***

|

-.195***

|

-.384***

|

.323***

|

.290***

|

| Coal |

.197***

|

n/s |

n/s |

-.189**

|

n/s |

| Electricity |

.331***

|

.211***

|

.273***

|

-.373***

|

n/s |

| Gas |

.173**

|

.197***

|

.221***

|

n/s |

-.236***

|

| Kerosene |

n/s |

n/s |

n/s |

n/s |

.122*

|

| Clean Fuels |

.367***

|

.323***

|

.380***

|

-.315***

|

-.299***

|

Table 8.

Income per Capita - Relationships with other demographic variables (country means).

Table 8.

Income per Capita - Relationships with other demographic variables (country means).

| Demographic Variables |

Pearson’s r |

| Age |

.617***

|

| Education level |

.665***

|

| Children under 15 |

-.547***

|

| Residents over 15 |

-.350***

|

| Access to internet |

.665***

|

| Employment |

.259***

|

| Rural/urban |

.447***

|

Table 9.

Regression - Personal health index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

Table 9.

Regression - Personal health index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

54.518 |

6.551 |

|

8.322 |

<.001 |

| Income per capita |

.000 |

.000 |

.228 |

2.785 |

.006 |

| Age |

-.331 |

.106 |

-.274 |

-3.134 |

.002 |

| Education level |

7.257 |

2.084 |

.273 |

3.482 |

<.001 |

| Rural/urban |

-12.361 |

3.140 |

-.362 |

-3.937 |

<.001 |

| Employment |

10.911 |

2.120 |

.316 |

5.146 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.133 |

.022 |

.648 |

5.968 |

<.001 |

Table 10.

Regression – Life evaluation index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

Table 10.

Regression – Life evaluation index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

1.175 |

.199 |

|

5.900 |

<.001 |

| Children under 15 |

.057 |

.023 |

.333 |

2.490 |

.014 |

| Residents over 15 |

-.090 |

.026 |

-.343 |

-3.500 |

<.001 |

| Access to internet |

.329 |

.106 |

.322 |

3.102 |

.002 |

| Rural/urban |

.135 |

.062 |

.152 |

2.199 |

.029 |

| Employment |

.202 |

.087 |

.235 |

2.329 |

.021 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.000 |

.001 |

.069 |

.528 |

.598 |

Table 11.

Regression analysis – Social life index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

Table 11.

Regression analysis – Social life index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

39.390 |

4.749 |

|

8.294 |

<.001 |

| Age |

.281 |

.084 |

.211 |

3.352 |

<.001 |

| Employment |

11.904 |

1.875 |

.333 |

6.349 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.071 |

.015 |

.304 |

4.789 |

<.001 |

Table 12.

Regression – Negative experience index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

Table 12.

Regression – Negative experience index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

51.766 |

5.841 |

|

8.863 |

<.001 |

| Income per capita |

.000 |

.000 |

-.183 |

-2.546 |

.012 |

| Education level |

-14.825 |

2.133 |

-.511 |

-6.951 |

<.001 |

| Rural/urban |

19.943 |

3.211 |

.536 |

6.211 |

<.001 |

| Employment |

-8.243 |

2.169 |

-.219 |

-3.800 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

-.097 |

.021 |

-.436 |

-4.639 |

<.001 |

Table 13.

Regression – Civic engagement index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

Table 13.

Regression – Civic engagement index and choice of clean cooking fuels.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

41.243 |

4.292 |

|

9.610 |

<.001 |

| Age |

-.501 |

.089 |

-.358 |

-5.604 |

<.001 |

| Education level |

8.337 |

1.706 |

.302 |

4.888 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

-.064 |

.018 |

-.256 |

-3.512 |

<.001 |

Table 14.

Wellbeing indices for intensive cooks and non-cooks (medians).

Table 14.

Wellbeing indices for intensive cooks and non-cooks (medians).

| |

Personal health |

Life evaluation |

Social life |

Negative experience |

Civic engagement |

| Intensive cooks |

67.3 |

2.18 |

80.2 |

32.0 |

32.4 |

| Non-cooks |

71.9 |

2.20 |

82.1 |

28.1 |

31.4 |

| Difference (non-cooks – intensive cooks) |

4.6 |

0.02 |

1.9 |

-3.9 |

-1.0 |

Table 15.

Regression – Personal health index as an outcome variable.

Table 15.

Regression – Personal health index as an outcome variable.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

55.024 |

6.331 |

|

8.692 |

<.001 |

| Income per capita |

.001 |

.000 |

.248 |

3.138 |

.002 |

| Age |

-.419 |

.105 |

-.347 |

-3.986 |

<.001 |

| Education level |

6.837 |

2.018 |

.257 |

3.388 |

<.001 |

| Employment |

10.380 |

2.054 |

.300 |

5.053 |

<.001 |

| Rural/urban |

-12.849 |

3.011 |

-.376 |

-4.267 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.084 |

.026 |

.407 |

3.262 |

.001 |

| Access to electricity |

.099 |

.028 |

.364 |

3.583 |

<.001 |

Table 16.

Regression – Life evaluation index as an outcome variable.

Table 16.

Regression – Life evaluation index as an outcome variable.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

1.160 |

.197 |

|

5.897 |

<.001 |

| Children under 15 |

.082 |

.026 |

.480 |

3.129 |

.002 |

| Residents over 15 |

-.118 |

.029 |

-.446 |

-4.006 |

<.001 |

| Access to internet |

.293 |

.107 |

.287 |

2.744 |

.007 |

| Employment |

.134 |

.061 |

.151 |

2.204 |

.029 |

| Rural/urban |

.202 |

.085 |

.235 |

2.361 |

.019 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.000 |

.001 |

-.032 |

-.230 |

.818 |

| Access to electricity |

.002 |

.001 |

.242 |

1.878 |

.062 |

Table 17.

Regression – Social life index as an outcome variable.

Table 17.

Regression – Social life index as an outcome variable.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

38.211 |

4.608 |

|

8.293 |

<.001 |

| Age |

.216 |

.083 |

.163 |

2.612 |

.010 |

| Employment |

10.566 |

1.838 |

.296 |

5.748 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

.008 |

.021 |

.035 |

.389 |

.698 |

| Access to electricity |

.120 |

.030 |

.364 |

4.057 |

<.001 |

Table 18.

Regression – Negative experience index as an outcome variable.

Table 18.

Regression – Negative experience index as an outcome variable.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

53.111 |

5.821 |

|

9.123 |

<.001 |

| Income per capita |

.000 |

.000 |

-.180 |

-2.526 |

.012 |

| Education level |

-14.603 |

2.119 |

-.503 |

-6.890 |

<.001 |

| Employment |

-7.986 |

2.158 |

-.212 |

-3.701 |

<.001 |

| Rural/urban |

19.951 |

3.163 |

.536 |

6.309 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

-.069 |

.026 |

-.308 |

-2.601 |

.010 |

| Access to electricity |

-.048 |

.028 |

-.162 |

-1.705 |

.090 |

Table 19.

Regression – Civic engagement index as an outcome variable.

Table 19.

Regression – Civic engagement index as an outcome variable.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant) |

40.572 |

4.261 |

|

9.521 |

<.001 |

| Age |

-.523 |

.092 |

-.376 |

-5.709 |

<.001 |

| Education level |

7.801 |

1.749 |

.283 |

4.461 |

<.001 |

| Choice of clean fuels |

-.083 |

.023 |

-.333 |

-3.542 |

<.001 |

| Access to electricity |

.043 |

.033 |

.123 |

1.301 |

.195 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).