1. Introduction

Patient safety has been a key topic on the quality improvement agenda of healthcare organizations since the beginning of the new millennium. Public and professional concerns over patient safety, medical errors, and adverse events have continued to increase, therefore these areas have rightly been used as fundamental criteria of healthcare accreditation processes [

1]. Patient safety culture is one of the key factors that determines the safety and quality in healthcare organizations [

2]. Safety culture is the awareness, knowledge, values, and perception of patient safety shared by all staff members in a healthcare organization [

3].

In a Canadian Adverse Event study [

4], it was estimated that the overall incidence of adverse events in Canadian hospitals was 7.5% of all admissions and this translates to 185,000 incidents and an estimated 70,000 being potentially preventable. A 2016 systematic review commissioned by the World Health Organization identified missed, delayed diagnoses and medication errors as the chief safety priorities in ambulatory care [

5]. This aspect is relevant to sports medicine hospitals where the primary concern is to assist athletes return to play or training at the earliest.

Patient safety culture is an important healthcare quality dimension and is an issue of high concern globally [

6,

7]. Patient safety culture refers to management and staff values, beliefs, norms, behaviours, attitudes, and what processes and procedures are rewarded and punished regarding patient safety.

Establishing a culture of patient safety in healthcare is essential to improve quality of care and promote patient safety [

8]. Organizational culture that encourages reporting, avoids blame, and enhances communication are reported as important factors to improve patient safety culture [

9].

To make improvements in patient safety, it is important for healthcare organizations to assess the status of their existing culture of patient safety and determine areas of priority to target for improvement [

10]. Deploying a survey tool such as Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) can support quality improvement by increasing staff awareness on issues related to safety. It is a rigorously designed tool that has been designed to measure patient safety culture [

11]. Previous studies in this domain have suggested that patient safety culture improves the quality of care, prevents errors, improves patient outcomes, and reduces healthcare costs.[

12] As the demand for quality in healthcare grows, healthcare organizations are faced with an increased need to establish a patient safety culture [

13].

Knowing factors contributing to patient safety would help organizations to establish and improve their culture. Understanding the overall patient safety grade helps organizations to benchmark their performance internally as well as with external healthcare organizations. Emphasis is placed on achieving “Excellent” or “Very Good” grade to assess the overall patient safety climate in these organizations. Regular deployment of the patient safety culture tool helps with trend data. Identification of strengths helps to sustain performance in these aspects and areas for improvement and facilitate action planning to improve performance in these specific areas.

There are no known previous studies that have evaluated factors associated with a safety culture at a sports medicine hospital. It is to our knowledge, the first time a study has been published in Qatar on patient safety culture and this study will contribute to the growing evidence on the importance of recognizing patient safety culture. The structure of a sports medicine hospital is usually different to a general hospital. Patients are mostly athletes and there is substantial component of ambulatory care and rehabilitation. Sports surgery facilities are available, and the scope of practice is restricted to sports-related injuries and treatment. The priority of the organization is to assist athletes to return to play at full potential at the earliest.

This study aimed to report on the patient safety culture and compare the patient safety grade with other settings. The overall objective of this study was to determine the factors that influence the grading of patient safety at a sports medicine hospital.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study design was employed for this study to obtain a baseline assessment of safety culture and to raise awareness about the safety cultures. The online survey was administered to all clinical and nonclinical staff in a sports medicine hospital (Aspetar, Doha - Qatar) during November 2018. The survey was bilingual – delivered in English and Arabic. Exclusions were any contracted third-party staff. It took an average of 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Aspetar is a specialised Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital where focus is mainly on medical treatment of sports related injuries. The structure of the hospital is composed of key medical departments, including sports medicine, musculoskeletal medicine, sports surgery, rehabilitation, sports dentistry, radiology, laboratory, sports podiatry, sports psychology, sports nutrition, pharmacy, research and medical clinics linked with sports clubs and federation in Qatar. It is staffed by more than 750 employees that include around 80% health care professionals. There is inpatient facility with 22 beds. Daily patient visits are about 400 per day and average number of surgeries per year is around 2000.

The survey tool used in this study was the version 1 of HSOPSC, developed by the Agency for Health Research and Quality to assess safety culture. The HSOPSC consists of 42 items that are categorized in 12 dimensions and two additional items related to the participant’s overall grade on patient safety for their work area/unit and to indicate the number of events they reported over the past 12 months.

The 42 questions in HSOPSC measure 12 aspects of the patient safety culture and are called dimensions or composites. These are the following: teamwork within units, supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting patient safety, organizational learning and continuous improvement, management support for patient safety, feedback and communication about errors, overall perceptions of patient safety, frequency of events reported, communication openness, teamwork across units, staffing, handoffs and transitions, and nonpunitive response to errors. Seven dimensions measure safety culture at the unit or departmental level. Three dimensions measure safety culture at the hospital level. The questionnaire also includes four outcome variables – frequency of events reported, overall perception of safety, patient safety grade, and number of events reported. Most questions ask staff to give agreement or frequency answers, using a Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree” or “never”) to 5 (“strongly agree” or “always”). Questions are also positively and reverse worded.

Additional data from the participants was collected related to their work area (clinical/nonclinical), background, years of experience in their profession, experience in the work unit and in the same hospital, and workload (work hours per week).

The factors assessed for patient safety as part of the survey include safety culture at hospital unit where the staff work, supervisor, communications, frequency of events reported, patient safety grade awarded, hospital safety culture and number of events reported.

The tool is an Accreditation Canada International requirement for the deployment of the Qmentum International accreditation program [

14]. For the survey, the demographic sections were identical to the original survey and administered online. Emails were sent to staff to access the survey through a web link. The surveys were deployed over a three-week period. The survey was advertised by email and staff were asked to participate. There were two email reminders sent to the participants in the period corresponding to one week before the closing date. The administration was anonymous and no personal information was collected that could identify the participants by name. Staff were provided access to laptops to complete the tool online during their work hours. We provided contact information for participants to seek clarification on any questions over web.

This study received ethical approval from Anti-Doping Lab Qatar (E2017000210). The confidentiality and anonymity of responses was maintained, and participants consented to participating in the online survey.

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) v 21.0. The categorical variables were presented as count and percentages. Dimension scores for each collaborative factor group were generated based on a four-step process, the “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses were identified for each question and indicated a positive response. For the questions that were reversed, a positive response was indicated with an answer of “Disagree” or “Strongly disagree”. The percentage of positive results were calculated for each collaborative factor, dimension scores were calculated as the average percentage of positive and negative responses for each question within each of the sections (Work Area / Supervisor/ Communication/ Frequency of Reporting and Hospital).

A chi-square test was performed to compare items of the tool to compare the binary categorical variable overall patient safety grade (very good/excellent vs failing/poor/acceptable). Items that were significant were considered for logistic regression analysis with overall patient safety and outcome variable and significant factors as potential covariates. Odds ratios with 95% CI were reported and P-value <0.05 was considered cut-off for statistical significance.

3. Results

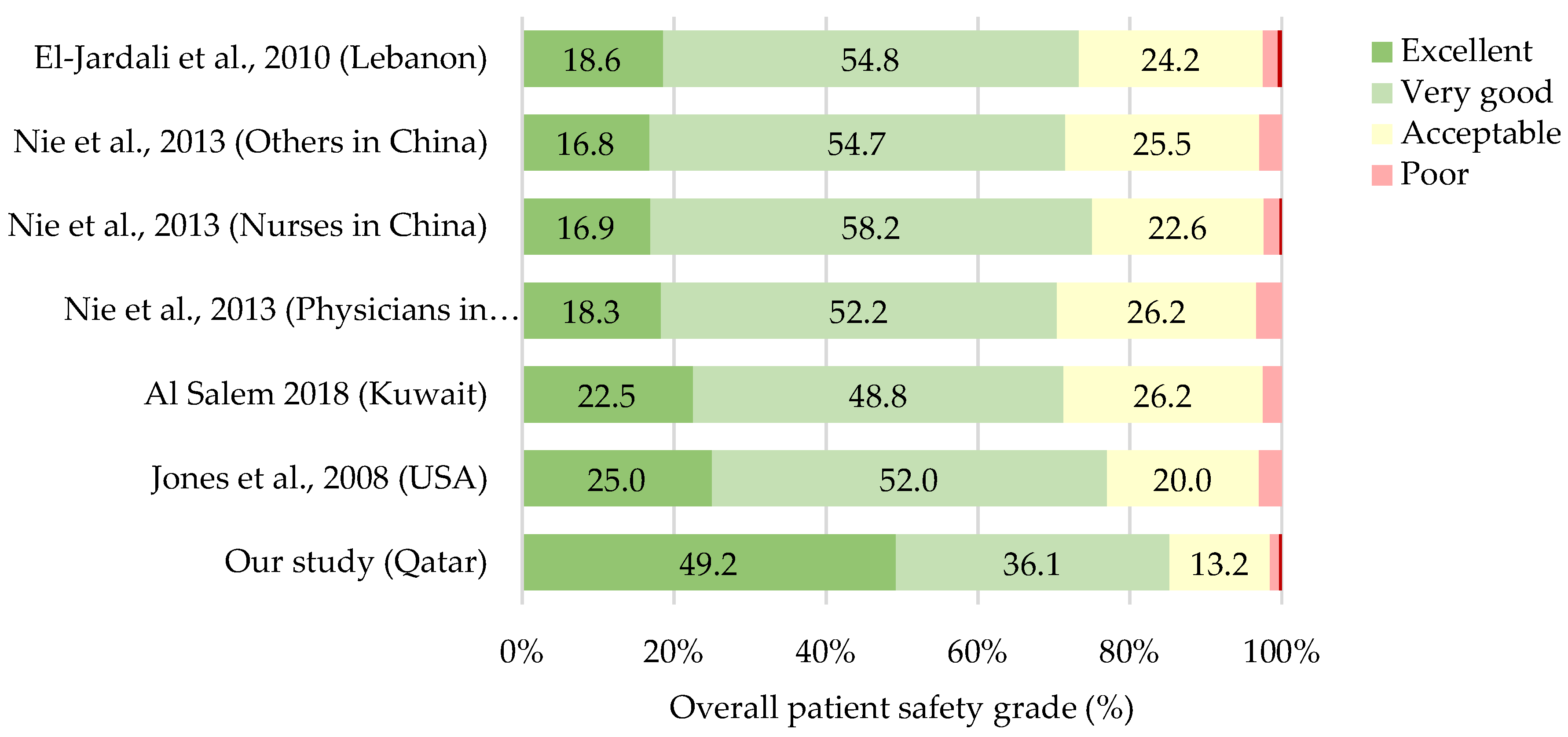

From the total of 898 staff, only 319 participated (35.5%) and provided completed forms. More clinical staff participated, 214 out of 504 clinical staff participated (42.4%) compared to 100 out of 394 nonclinical staff (25.3%). Overall, the positive staff rating for the hospital patient safety grade stood at 85.3% that included 49.2% as excellent and 36.1% as very good. Only 13.2% rated patient safety grade as acceptable, 1.3% as poor and 0.3% as failing. Of the 100, non-clinical staff (87.0%) reported a better patient safety grade (very good/excellent) as against clinical staff (180/214, 84.1%).

3.1. Staff Characteristics.

There were no differences among Qatari and non-Qatari staff regarding their rating on overall patient safety grade (P=0.946). Length of employment in their current role did not impact the overall patient safety grading significantly. Staff who have worked in the hospital ≤ 5 years (86.6%) rated better on the patient safety grade than staff who have worked in the hospital for more than 5 years (84.4%) (P=0.581) (

Table 1). Hours of work per week at the hospital did not influence the patient safety grading (P=0.645).

Staff that did not have direct patient contact (87.6%) rated the patient safety grade as very good/excellent compared with clinical staff (83.9%) that provided the same rating (P=0.388). Employees who had less than five years of experience in their profession (87.2%) rated the patient safety grade as very good/excellent as compared with staff that had more than five years of experience (84.8%). Clinical and non-clinical staff rated similarly (P=0.504) and staff that reported events in the past were no different compared to staff that did not report events on overall patient safety grade ratings (P=0.223).

3.2. Work area / Unit

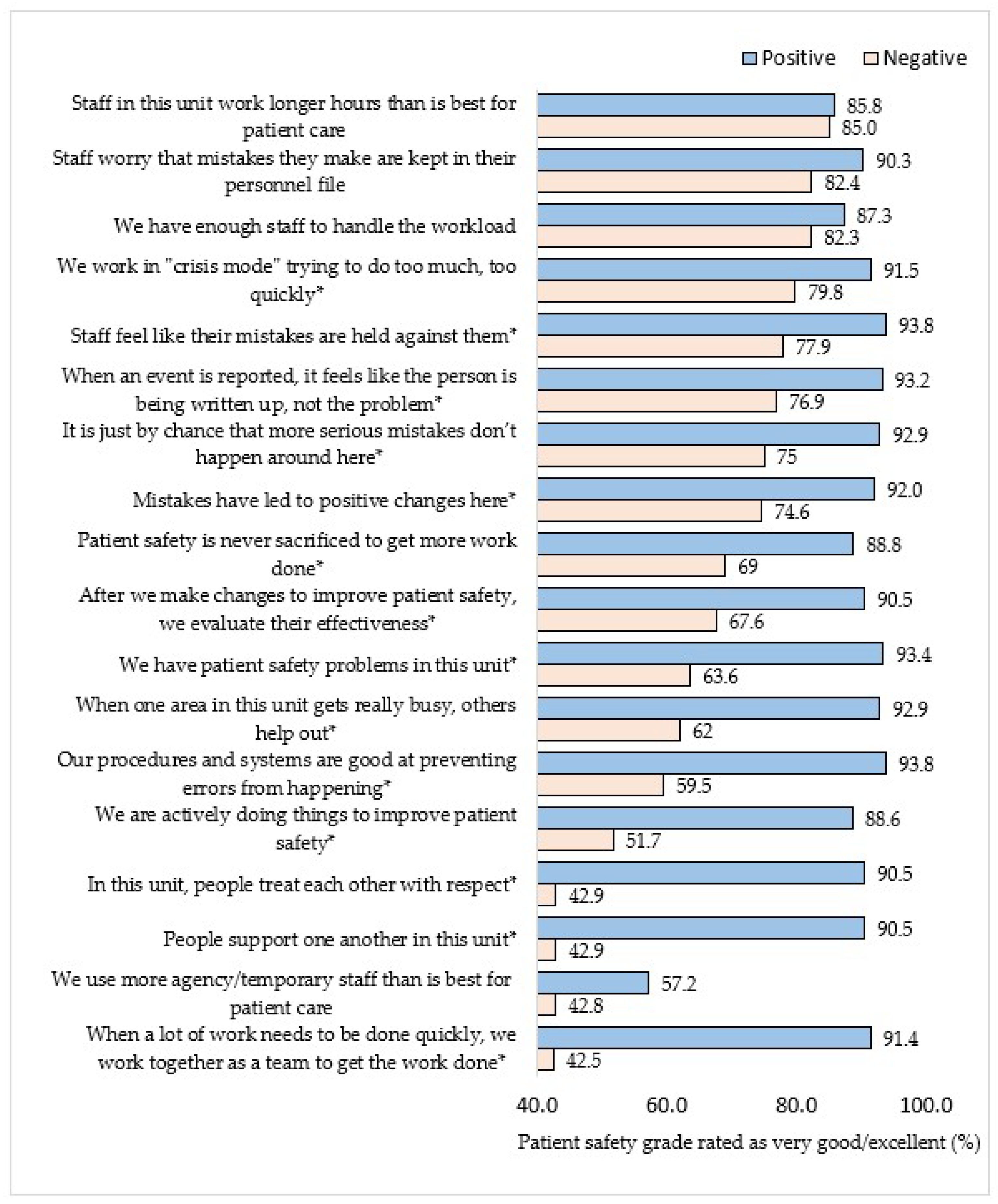

Participants who were positive that people support one another in their unit gave a higher rating for safety culture (90.5%) compared to those who were negative about people supporting one another in their unit (42.9%), P<0.001) (

Figure 1.). Participants who supported working together as a unit to complete work quickly, treating each other with respect, and actively doing things to improve patient safety provided a better patient safety grade at the hospital (P<0.001) compared to those participants that did not consider these items as important. Participants who did not report patient safety problems on their unit provided a better patient safety grade for the hospital (93.4%) compared to those who believed that there are problems in their unit (63.6%), (P<0.001). Staff who believed their mistakes are held against them were more likely to report higher overall patient safety grade rating (93.8%) compared to who didn’t (77.9%), P<0.001.

3.3. Supervisor

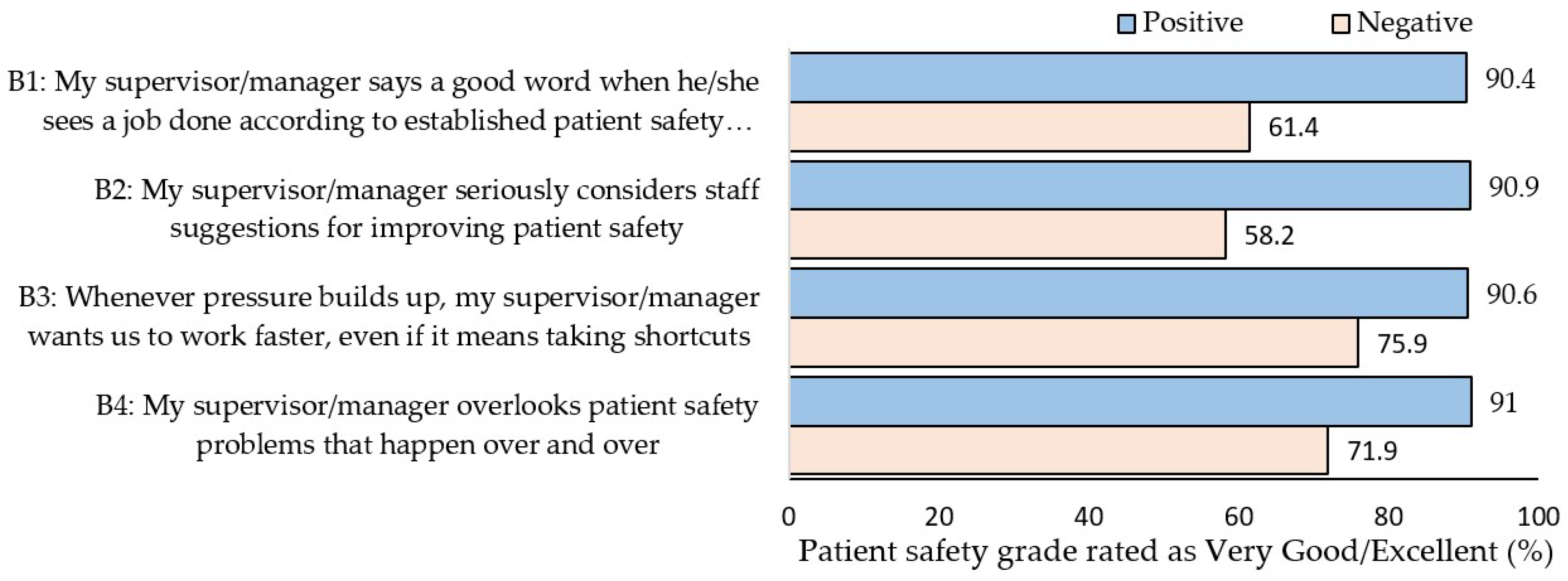

Staff who reported that their supervisor appreciates their work related to patient safety practices awarded the hospital a better patient safety rating (90.4%) compared to those participants who reported that supervisors do not appreciate their work (61.4%), (P<0.001) (

Figure 2). Staff whose supervisor seriously considered staff suggestions for improving patient safety awarded the hospital a better patient safety grade (90.9%) than the supervisor that doesn’t (58.2%), (P<0.001). Participants who reported that the supervisor doesn’t support any shortcuts at work that impact patient safety awarded a better patient safety grade (90.6%) than supervisor that supports shortcuts (75.9%) (P<0.001). Similarly, staff whose supervisor doesn’t overlook patient safety problems awarded a better patient safety grade (91.0%) than staff whose supervisor does (71.9%), (P<0.001).

3.4. Communication

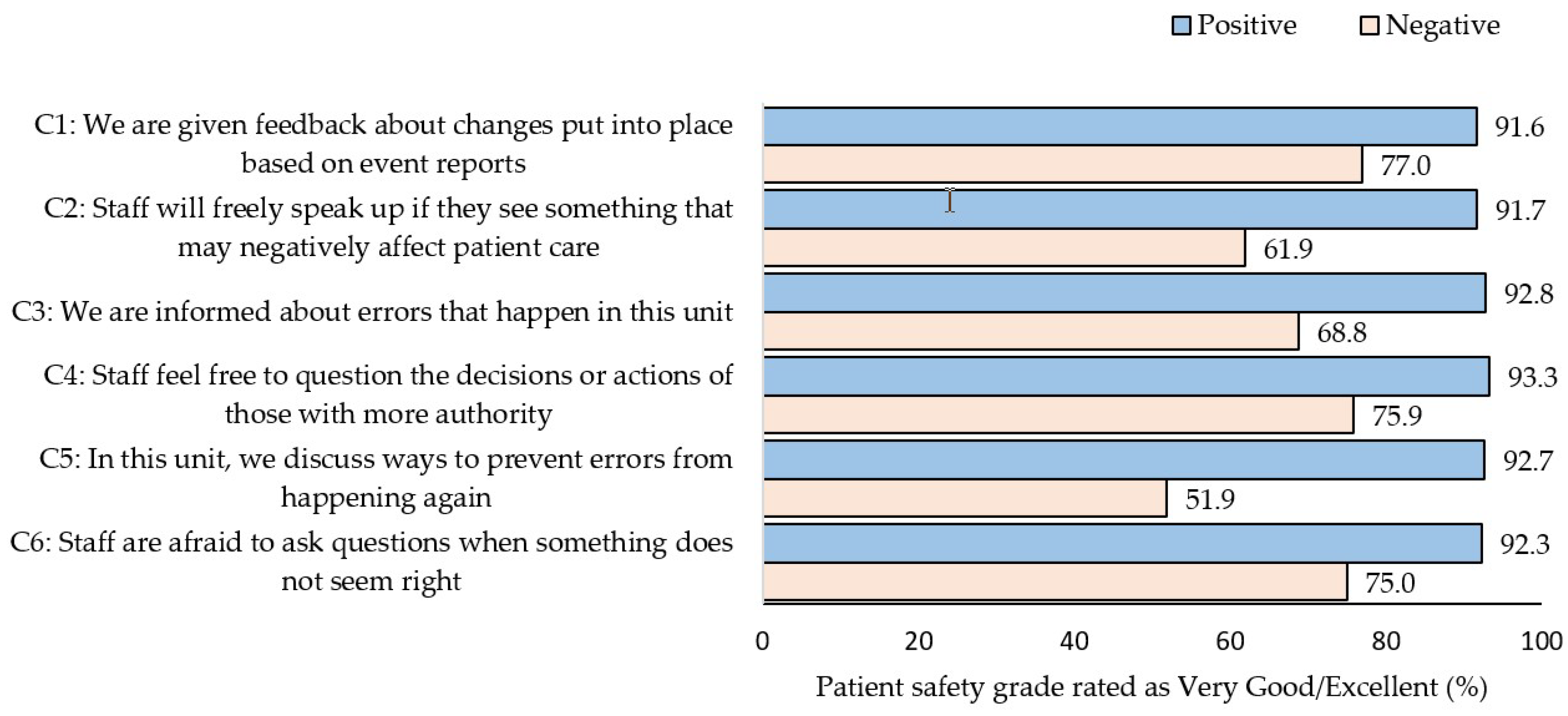

Out of the six items for HSOPC related to communication, item concerning discussions on ways to prevent error from happening again in their units was significant (P<0.001). The staff who reported positively on this item awarded a better patient safety grade (92.7%) compared to staff who did not (51.9%), (p<0.001) (

Figure 3). Furthermore, when staff are given feedback, informed about errors, allowed to speak freely, and ask questions were more likely to give a higher overall patient safety grade rating (P<0.001).

3.5. Frequency of Events Reported

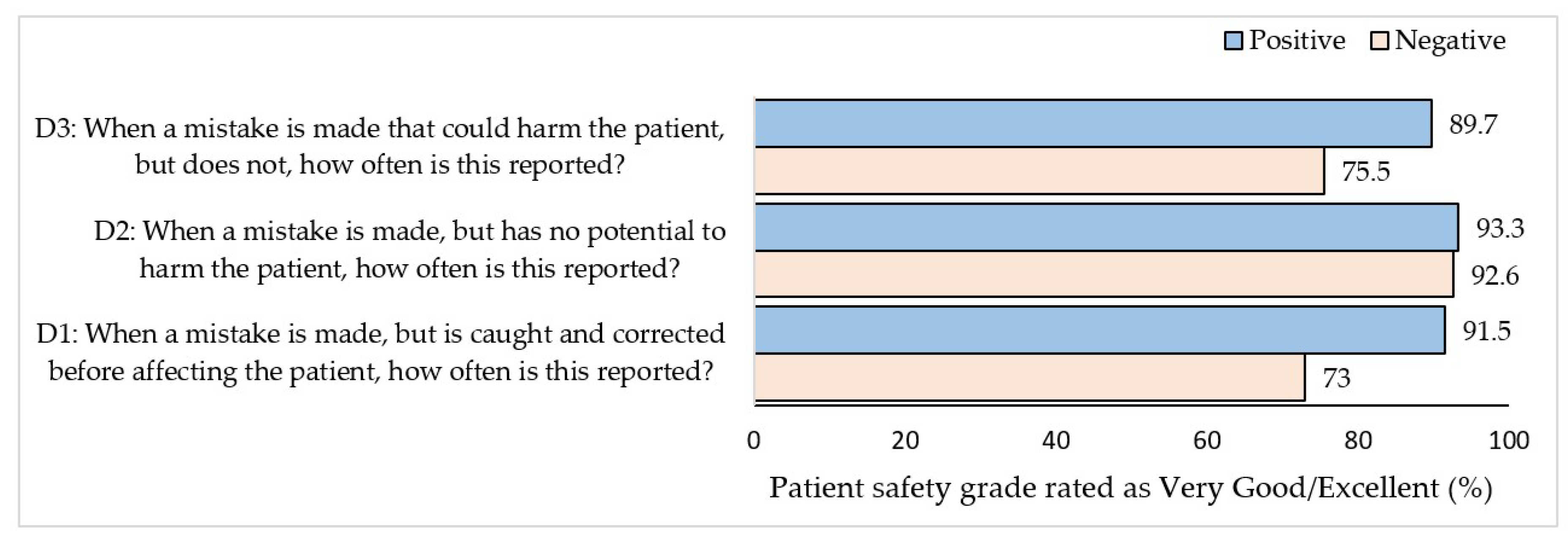

Staff that reported a mistake most of the time or always, even when there was no potential for patient harm, awarded a better patient safety grade than staff that did not in all three items (P≤0.001 (

Figure 4)).

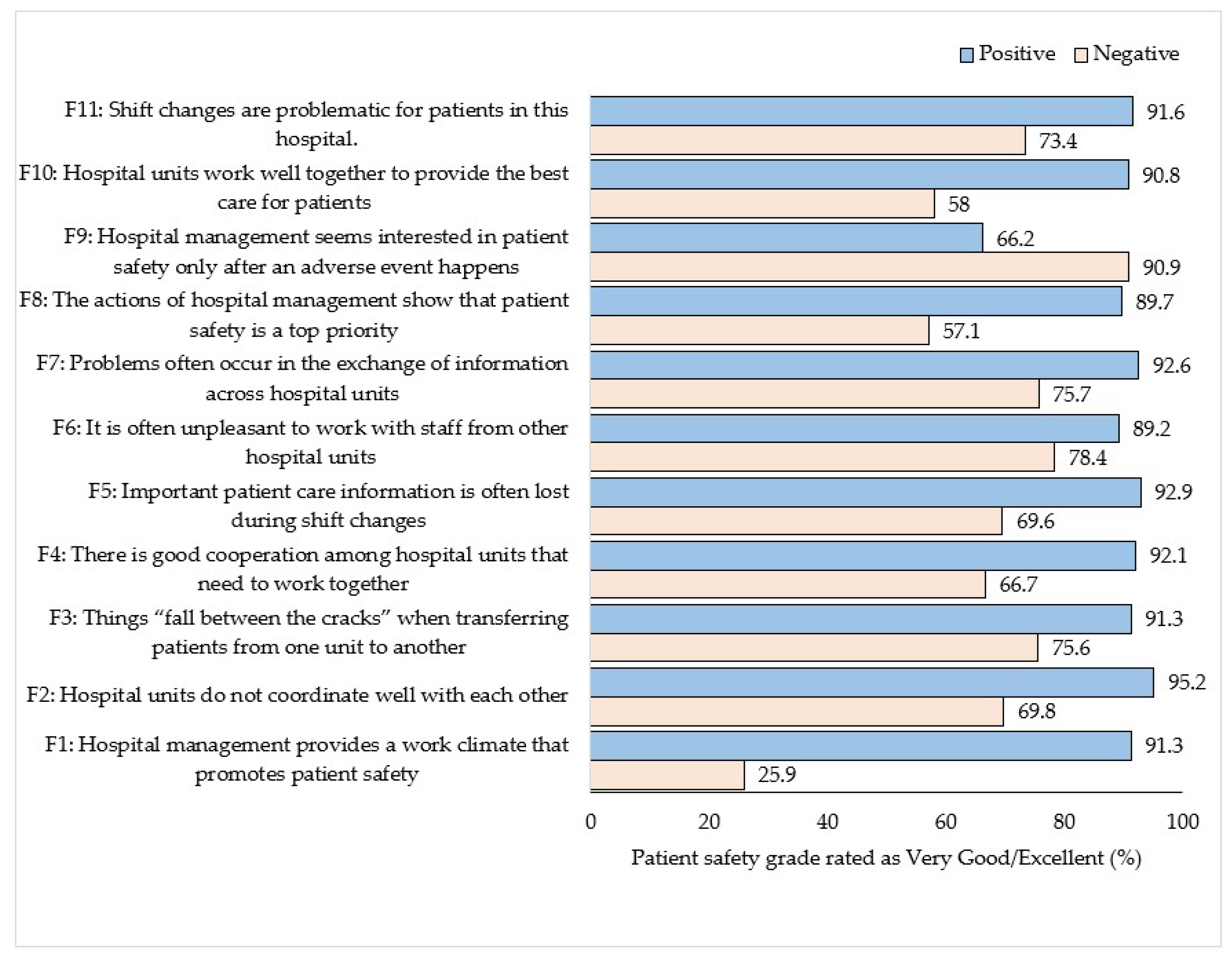

3.6. Hospital

Staff that reported that the hospital management provides a work climate that promotes patient safety provided a better patient safety grade (91.3%) than staff that did not (25.9%), P<0.001 (

Figure 52Pollu). When participants perceive hospital units to coordinate well with each other, they provide a better patient safety grade (95.2%) compared to those who perceive that they do not coordinate well with each other (69.8%) P<0.001. Participants who rated that patient care information is not lost during shift change also rated high on the overall patient safety grade (92.9%) compared to those who responded that patient care information is lost during shift changes (69.6%). (P<0.001). Staff who believed that actions by hospital managements that show that patient safety is a top priority rated higher on overall patient safety grade (89.7% compared to 57.1%, p<0.001). Staff who disagreed that hospital management seems to be only interested in patient safety after an adverse event were more likely to rate higher overall patient safety grade (90.9% vs. 66.2%, p<0.001).

The logistic regression analysis revealed hospital management providing a work climate that promotes patient safety was associated with increased odds for very good/excellent overall patient safety grade (OR = 10.3, P<0.001) (

Table 2). Staff reported that when a lot of work needs to be done quickly, they come together as a team to achieve this task were associated with awarding a very good/excellent patient safety grade (OR=7.6, P<001). When staff most of the time and always discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again improves the odds of reporting a better patient safety grade. (OR 2.9, P=0.026). When staff agree that there are no patient safety problems in their unit, it was associated with better patient safety grade (OR=2.8, P=0.026). Participants who agreed important patient care information is rarely lost during shift changes was associated with a positive patient safety grade (OR=2.6, P=0.038).

4. Discussion

4.1. Statement of principal findings

This study reported that at a sports medicine hospital the overall patient safety grade as assessed by staff was 85.3% (Excellent or Very Good). The percentage of ‘excellent or very good’ overall patient safety grade achieved in this study is better than similar studies that assessed the patient safety grade (77.0%) at 21 critical access hospitals in the USA [

15], (60.0%) at 13 general hospitals in Saudi Arabia [

16] , (70.3%) at 3 public hospitals in Kuwait [

17], (70%) at 68 hospitals in Lebanon [

18], and (73.0%) at 32 hospitals in 15 cities in China [

19] (

Figure 6).

4.2. Interpretation within the context of the wider literature

On further analysis of our data, there was a statistically significant association between the selected factors that were associated with ‘Excellent/Very Good’ patient safety grade. In our study, we noticed that when the hospital management provides a

work culture that promotes patient safety, there is a significant improvement in patient safety grade provided to the hospital and this is evidence of a just culture [

15].

When a lot of work needs to be done quickly, “we work together as a team to get the work done” shows the willingness of staff to work on common goals and this is an evidence of a flexible culture.

Teamwork within work areas/units is critical to ensure that there is improved safety in their work area/unit [

20]. Higher scores on teamwork increase the likelihood of participants to report a higher patient safety grade in consistence with other studies [

21,

22] Staff who reported that their mistakes are held against them were more likely to report higher overall patient safety grade rating suggesting that an environment where healthcare providers are accountable for quality of care will lead to improved patient safety [

23].

Good communication with and across healthcare teams is the key to mitigating any threats to patient safety [

18]. Results from our study show a significant association between open discussions on patient safety and a positive patient safety grade [

24]. When there is discussion in teams on ways to prevent errors from happening again, this shows a positive patient safety culture and is an evidence of a learning culture.

When staff confirm that they do not have safety problems on their teams they awarded a positive patient safety grade. This is evidence of an informed culture agreeing with other similar studies in Lebanon [

18,

22] and Oman [

21].

When staff say that important patient care information is rarely lost during shift changes, it is an evidence of an informed culture [

15]. Higher scores on handoffs and transitions increased the likelihood of having a better perception of safety among participants and the likelihood of these participants to award a better patient safety grade.

The results on factors that influence the patient safety grade are consistent with previous published research which demonstrated that the safety culture varies by position and area of work [

20,

21]. Specifically, this relates to staff that do not deliver direct patient care, rating the patient safety grade higher than staff that deliver direct patient care [

15]. This may be due to a perception of a punitive culture [

11,

25,

26,

27,

28].

The results show that there is strong evidence of a growing interest among healthcare organizations to assess the safety culture and use it as a tool for improvement [

29].

4.3. Implications for policy, practice and research

The study contributes to the growing evidence that the establishment of a culture of patient safety is important to move the organization across the quality continuum. There are important implications for practice including positive attitude towards patient safety by staff improves the patient safety grading of a hospital. It is vital to improve teamwork between units to improve patient safety. Further analysis is recommended to identify the presence of microcultures within organizations so that customized interventions can be implemented.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This is the first study of patient safety grade in a Sports Medicine Hospital setting. Although the data collected from participants had very low incomplete responses, there were few limitations to consider. The response rate was low (36%), however, this is generally accepted that web-based has a lower response than in-person surveys [

30]. The web-based surveys also provide more anonymity compared to face-to-face interviews where there is a risk of identification and external influence.

5. Conclusions

The overall patient safety grade achieved in this study is significantly better than similar studies that assessed the patient safety grade in hospitals. To create a culture of safety and improvement, healthcare leaders must create a climate of open communication for staff within their own work areas, as well as in the overall organization as these are key factors that influence the overall patient safety grade [

31]. Ensuring quick return to play is a team game involving multiple disciplines, hence a high performance and safety culture can enhance teamwork facilitating this aspect [

29]. Consistent to our findings, emphasis must be placed on reducing punitive response to error and having supportive supervisors in order to improve safety culture [

11,

25,

27,

28].

Essentially, the deployment of the HSOPSC on a regular basis helps to measure the patient safety pulse of an organization and identify and make relevant improvements [

32]. The results of this study can be used to plan targeted interventions. Leaders can use the data and facilitate a culture of trust that encourages two-way communication across healthcare organizations.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.A. and A.F.; methodology, S.A. and A.F.; software, A.F.; validation, S.A. and A.F.; formal analysis, S.A. and A.F.; investigation, S.A., S.R. and A.F.; resources, S.A. and S.R.; data curation, S.A. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, S.A., S.R. and A.F.; visualization, S.A. and A.F.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by Qatar Anti-Doping Lab Ethics Committee (Doha, Qatar; approval number: E2017000210). All participants participated voluntarily, and their personal information remained confidential.

Informed Consent Statement

“Patient consent was waived since participation in the survey was anonymous, and participation was voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Mr. Irwin Vilaga and Mr. Ronald Barangan, for assisting in the distribution of survey to the participants during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Accreditation Canada. Qmentum Accreditation Program. Available online: https://accreditation.ca/qmentum-accreditation/ (accessed on 30 March).

- Alex Kim, R.J.; Chin, Z.H.; Sharlyn, P.; Priscilla, B.; Josephine, S. Hospital survey on patient safety culture in Sarawak General Hospital: A cross sectional study. Med J Malaysia 2019, 74, 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Huong Tran, L.; Thanh Pham, Q.; Nguyen, D.H.; Tran, T.N.H.; Bui, T.T.H. Assessment of Patient Safety Culture in Public General Hospital in Capital City of Vietnam. Health Serv Insights 2021, 14, 11786329211036313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.R.; Norton, P.G.; Flintoft, V.; Blais, R.; Brown, A.; Cox, J.; Etchells, E.; Ghali, W.A.; Hébert, P.; Majumdar, S.R.; et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. Cmaj 2004, 170, 1678–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, S.S.; deSilva, D.; Carson-Stevens, A.; Cresswell, K.M.; Salvilla, S.A.; Slight, S.P.; Javad, S.; Netuveli, G.; Larizgoitia, I.; Donaldson, L.J.; et al. How safe is primary care? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2016, 25, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wami, S.D.; Demssie, A.F.; Wassie, M.M.; Ahmed, A.N. Patient safety culture and associated factors: A quantitative and qualitative study of healthcare workers’ view in Jimma zone Hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronovost, P.J.; Berenholtz, S.M.; Goeschel, C.A.; Needham, D.M.; Sexton, J.B.; Thompson, D.A.; Lubomski, L.H.; Marsteller, J.A.; Makary, M.A.; Hunt, E. Creating High Reliability in Health Care Organizations. Health Services Research 2006, 41, 1599–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Li, H.H. Measuring patient safety culture in Taiwan using the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC). BMC Health Serv Res 2010, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, M.; Roback, K.; Öhrn, A.; Rutberg, H.; Rahmqvist, M.; Nilsen, P. Factors influencing patient safety in Sweden: perceptions of patient safety officers in the county councils. BMC Health Services Research 2013, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, V.F.; Sorra, J. Safety culture assessment: a tool for improving patient safety in healthcare organizations. Qual Saf Health Care 2003, 12 Suppl 2, ii17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, R.; Dimova, R.; Tornyova, B.; Mavrov, M.; Elkova, H. Perception of Patient Safety Culture among Hospital Staff. Zdr Varst 2021, 60, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, L.; Gilin Oore, D. Patient safety climate strength: a concept that requires more attention. BMJ Qual Saf 2016, 25, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaffary, A.; Al Yaqoub, F.; Al Madani, R.; Aldossary, H.; Alumran, A. Patient Safety Culture in a Teaching Hospital in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: Assessment and Opportunities for Improvement. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 3783–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Canada. Qmentum Accreditation Program. Available online: https://accreditation.ca/accreditation/qmentum/ (accessed on 5 October).

- Jones, K.J.; Skinner, A.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.; Mueller, K. Advances in Patient Safety: The AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: A Tool to Plan and Evaluate Patient Safety Programs. In Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign), Henriksen, K., Battles, J.B., Keyes, M.A., Grady, M.L., Eds.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville (MD), 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmadi, H.A. Assessment of patient safety culture in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care 2010, 19, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Salem, G.F. An assessment of safety climate in Kuwaiti public hospitals. University of Glasgow, 2018.

- El-Jardali, F.; Jaafar, M.; Dimassi, H.; Jamal, D.; Hamdan, R. The current state of patient safety culture in Lebanese hospitals: a study at baseline. Int J Qual Health Care 2010, 22, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Mao, X.; Cui, H.; He, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, M. Hospital survey on patient safety culture in China. BMC Health Services Research 2013, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.P.; McAlearney, A.S.; Pennell, M.L. The influence of organizational factors on patient safety: Examining successful handoffs in health care. Health Care Manage Rev 2016, 41, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammouri, A.A.; Tailakh, A.K.; Muliira, J.K.; Geethakrishnan, R.; Al Kindi, S.N. Patient safety culture among nurses. Int Nurs Rev 2015, 62, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Jardali, F.; Dimassi, H.; Jamal, D.; Jaafar, M.; Hemadeh, N. Predictors and outcomes of patient safety culture in hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2011, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Phan, P.H.; Dorman, T.; Weaver, S.J.; Pronovost, P.J. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabri, M.; Boudi, Z.; Lauque, D.; Dias, R.D.; Whelan, J.S.; Östlundh, L.; Alinier, G.; Onyeji, C.; Michel, P.; Liu, S.W.; et al. Impact of Teamwork and Communication Training Interventions on Safety Culture and Patient Safety in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. J Patient Saf 2022, 18, e351–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khater, W.A.; Akhu-Zaheya, L.M.; Al-Mahasneh, S.I.; Khater, R. Nurses' perceptions of patient safety culture in Jordanian hospitals. Int Nurs Rev 2015, 62, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, J.H.H.; Galvao, T.F.; Silva, M.T. Healthcare Professional's Perception of Patient Safety Measured by the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2018, 2018, 9156301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillivan, R.R.; Burlison, J.D.; Browne, E.K.; Scott, S.D.; Hoffman, J.M. Patient Safety Culture and the Second Victim Phenomenon: Connecting Culture to Staff Distress in Nurses. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2016, 42, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, R.R.; Calidgid, C.C. Patient safety culture among nurses at a tertiary government hospital in the Philippines. Appl Nurs Res 2018, 44, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azyabi, A.; Karwowski, W.; Davahli, M.R. Assessing Patient Safety Culture in Hospital Settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, N.; Radler, B. A comparison between mail and web surveys: Response pattern, respondent profile, and data quality. Journal of official statistics 2002, 18, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Alsabri, M.; Castillo, F.B.; Wiredu, S.; Soliman, A.; Dowlat, T.; Kusum, V.; Kupferman, F.E. Assessment of Patient Safety Culture in a Pediatric Department. Cureus 2021, 13, e14646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampetro, P.J.; Segvich, J.P.; Jordan, N.; Velsor-Friedrich, B.; Burkhart, L. Perceptions of Pediatric Hospital Safety Culture in the United States: An Analysis of the 2016 Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. J Patient Saf 2021, 17, e288–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).