1. Introduction

Early researchers proposed that the environment can contribute to the health benefits of individuals and society by reducing stress, alleviating anxiety, and reducing feelings of fear[

1,

2,

3]. Even just taking walks in natural environments has been found to be beneficial for health[

4].

However, Since Geslers[

5,

6] proposed the study of therapeutic landscapes, it has directed a new topic for the study of medical geography: why are certain places or situations considered therapeutic? There have been a number of studies exploring the healing and health-enhancing dimensions of places[

7]. Following Gesler's work, researchers have recognized the importance of maintaining health and well-being, which extends far beyond healing experiences. Moreover, what matters more is the quality of the relationship between therapeutic landscapes and the individual's experience[

7]. This shift acknowledges that places inherently do not possess healing properties; instead, it is through the dynamic interaction between individuals and their environment that opportunities for health and well-being are generated[

8].

In recent years, there has been significant progress in the research on therapeutic landscapes within the physical, social, and symbolic dimensions, particularly regarding ‘nature-based’ therapeutic encounters[

7]. Notably, there has been fruitful exploration of sensory responses to the environment, with a focus on engaging with the processes and temporalities of intimate, visceral place sensing[

9]. ‘Nature-based’ therapeutic encounters view the body as an instrument for perceiving and sensing the social environment, rather than merely as a container. Rather, bodies help constitute that reality, through our doings within it[

10]. We must delve into a more intricate understanding that acknowledges the significance of our bodily experiences in the world. It involves comprehending how we actively create and transform the world through skillful sensory activities[

11]. On the other hand, an alternative perspective suggests that external bodily injuries can stabilize when participants become aware of bodily changes, recognize the impact of external materials, and engage in reciprocal changes within the body[

12]. Therefore, bodily health should not be seen merely as an individual quality but rather emerges from attunements and resonances between bodies and materials[

13].

Currently, research on environmental healing tends to focus on green landscapes(For example, parks, green spaces, forests, mountains as well as even virtual green spaces[

14,

15]), and quantitative indicators are predominantly used. This approach can be considered a "symptom-oriented" method, where specific themed healing environments such as hot springs and forests (distinct from everyday living spaces) provide possibilities for users to temporarily escape emotionally stimulating situations[

16,

17], While these environments can achieve immediate physiological stress reduction (as measured by indicators) [

14,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], the long-term of healing effects remains unknown, as most studies only involve one-[

14,

15,

20,

21]. Although significant, the effects were observed only in the short term, highlighting the limitation of the capturing cross-sectional data and virtual experiences[

15]. It is important to discuss the possibility that participants may experience short-term negative emotional displacement due to the enchanting scenery, and this should be considered from different perspectives.

Cognitive control is the ability to process information over time to guide behavior in accordance with current goals [

22]. Recent research has also found that cognitive control is a key feature in adapting our behavior to environmental and internal demands. [

23]. Research indicates that as the body is in constant contact with the environment, more cognitive behavior emerges from situational action [

24], Previous research has also found that both landscape restoration and psychological restoration can be recognized simultaneously in body-environment interactions. [

25]. This study will further deepen the research on the relationship between interactive behavior and therapeutic landscape.

Despite data indicating the therapeutic nature of places such as forests, mountains, or hot springs in terms of participating in healing or enhancing health, there has been relatively less consideration of the dynamic relationships that underlie these therapeutic effects[

7]. What's more, the proposal of therapeutic landscape stems from the resistance to the hegemony of the biomedical model[

6]. We should focus on the interaction between people and the environment, rather than chasing which environment has a healing function. The value of living in the present is deliberately excluded in various studies that pursue amazing experiences. To reproduce this value, then is the main purpose of this study.

1.1. The inseparability of the body and everyday living space

Research suggests that long-term and immersive interactions between individuals and their environment are better able to meet diverse therapeutic needs[

26]. Well-being is a state beyond the individual body index, and also comes from the positive development between the body and the surrounding environment[

13]. Therefore, this study responds to scholars who argue that the body should be repositioned within a broader interdisciplinary discourse surrounding nature, health, and well-being [

9,

10]. Whether the subject matter of traditional landscape ideas derived from cultural geography, human geography, structuralist geography, and holistic health principles, the internal meaning implicit in everyday activities is one important reason for the therapeutic efficacy of landscapes[

6].

Bachelard gives primacy to deep or archetypal emotions that come not from the subject but from living space[

27]. It is everyday recreation that takes them out of their subjective and human-centered emotional states into the spatial-temporal depths of the relational state of ‘well-being’[

28]. Even in just a small corner of the world, focusing on the connection between emotions and living space can foster a more expansive worldview[

29].

1.2. The therapeutic imagery of the coastal zone

The cultural interpretation of the coast is constantly evolving, from its enjoyment amongst the Ancient Greeks and Romans as a place of pleasure and beauty[

26]. And then, the ocean is also filled with fear. The sea has been associated with various metaphors of rage and symbolizes various wild and untamed creatures.

“The ocean dances with a mane of lions; the sea spray is likened to "the drool of sea monsters" and is said to cling to their claws” [

27].

Human geographers have focused more precisely on the coastal zone. The characteristics of concave coasts evoke a sense of safety, while the expansive horizon stimulates human adventurous desires. Especially throughout the 19th century, the coastal zone provided happiness and health to humans, with its value surpassing its economic output[

30]. It was only after people recognized the health benefits of sea bathing that health enthusiasts turned their attention to the coast, shifting from thermal springs[

31,

32]. The coastal zone has also served as an environment for sustenance, learning, and the earliest human habitats[

33]. Cultural geographers[

29]have commented on the potential of the coast to “

generate a palpable intensity of feeling”[

34].

Research has shown the therapeutic benefits of coastal restoration[

35], including physiological, mental-emotional, and creativity-related benefits [

36,

37,

38], The coastal zone is also regarded as a daily therapeutic space[

26], where the frequency of visiting blue spaces is positively correlated with psychological well-being, happiness, and physical activity levels[

39]. Moreover, interactions with the coast often involve enduring connections[

26]. Studies have also shown that emotional attachments formed in everyday life in the coastal zone can lead to a profound understanding of the interests at stake in local development and inspire actions to play a role[

40].

Since the 19th century, the coastal zone has seemingly become synonymous with holiday and leisure, leading to the neglect of its significance as a daily living space for local residents. Therefore, for the therapeutic landscape of the coastal zone, it is lacking in previous studies to separate the recreational components. Furthermore, compared to green spaces such as mountain, forests, parks, and gardens, the therapeutic landscape of the coastal zone has received less attention from the academic community[

26]. However, within the broader literature, the coast has been conceptualised as a ‘therapeutic landscape’[

8,

9,

41].

On the other hand,Gesler notes that “what is therapeutic must be seen in the context of social and economic conditions and changes”[

42]. Durling period of the COVID-19 pandemic, which occurred between 2020 and 2022, has indeed brought about changes in the relationship between individuals and spaces. The experience of lockdown has made people more aware of their connection with nature[

43,

44]. Studies on lockdown during the pandemic have indicated that the absence of interactions with the coastal zone can disrupt the imagery of home[

45]. The imagery of home serves as a sanctuary, a place of healing, regardless of one's physical location. However, understanding how individuals establish a sense of home and emotional connection with the coastal zone is a crucial aspect to consider.

Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to focus the theme of the therapeutic landscape on the daily life of the coastal zone; and explain which elements of everyday life come together to form the therapeutic landscape.

In this paper I seek to address this absence through engagement with two related bodies of work: pay attention to the relationship between daily life and body, as well as the local people living in the coastal zone. Moreover, the process should be a state of long-term interaction between people and the coastal zone, focusing on frequency.

According to the above purpose and literature review, the hypotheses of this study are as follows:

Residents living in the coastal zone, the way to heal themselves is to interact with the environment, and its factors are affected by the frequency of visiting the coastal zone, gender, and perception methods (including facial senses and body).

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a continuation of the landscape resilience perspective [

25], with a specific focus on the relationship between local residents and their everyday living spaces. In addition to utilizing literature and oral data as suggested by Geslers[

6], scholars have also recommended the careful use of interviews, combined with more structured techniques, to record the forms and characteristics of individual-environment interactions, leading to a deeper understanding of the interactive relationship between people and their environment[

7]. Therefore, this study further adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods, to explore therapeutic issues and provide a more profound response to the people-centered nature of social science.

This study adopts a qualitative research approach to explore the methodology of dynamic processes. It posits that the more frequently the body is used in the environment, the more cognition emerges from the dynamic activities of contextual actions, leading to an awareness of interactive relationships, sense of place, and symbolic landscapes. The research methodology involves the use of participant observation and in-depth interviews to collect data. After data categorization and logging, SPSS is employed for data analysis.

2.1. The study area

There has been a substantial increase in recent years in scholarship exploring the therapeutic landscape experiences in China[

9]. These studies are predominantly located in the northwest region, exploring yellow sand therapy[

41,

46] and targeting the elderly population within urban areas[

47,

48]. However, there is a notable lack of research on therapeutic landscapes in coastal areas. Therefore, this study sets its research location in the fastest-growing city along the southeast coast.

Prior to 1980, China's focus on resource utilization was primarily centered around land resources, with relatively less attention given to marine resources[

49]. However, with rapid economic development, coastal provinces in China have become the fastest-growing regions. The high intensity of coastal land development and dense population concentration, coupled with investments from coastal cities and foreign countries, have intensified maritime economic activities. These intensive marine utilization activities have led to significant social and environmental changes, increased resource and environmental pressures, coastal pollution, and a decline in ecosystem health, resulting in escalating potential environmental risks[

50,

51,

52,

53]. Xiamen City, as early as 1994, became a pioneer in coastal management in China and a pilot city for the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) organization[

54]. Therefore, coastal governance in Xiamen bears the responsibility of sustainable development of marine resources and has received strong political support[

52]. The development goals have been oriented towards a tourism city. From 2010 to 2021, the Xiamen municipal government shifted the function of the coastal area from tidal flat aquaculture to tourism and recreation, thereby transforming the entire coastal landscape.

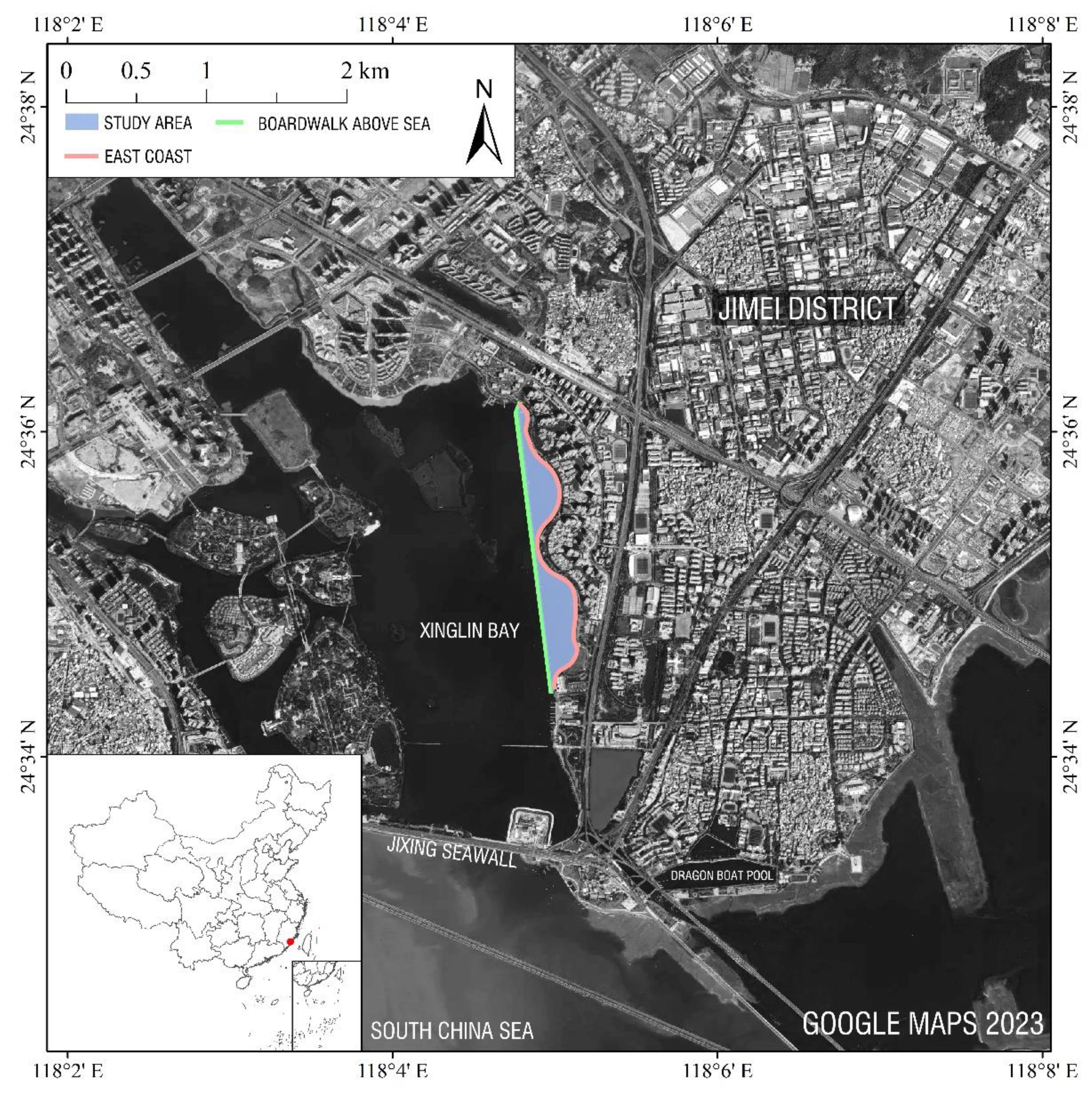

Xinglin Bay is located in the center of the Jimei Cultural and Educational District, attracting a large population due to its educational resources. It serves as a daily living space for Xiamen local residents. In 1979, the formation of a semi-enclosed water area occurred due to the construction of beach embankments, resulting in a unique characteristic of "half seawater, half freshwater" in the area. However, the rapid deterioration of the ecological environment took place as a result of industrial wastewater being discharged into Xinglin Bay from upstream industrial developments. Subsequently, Xiamen City actively promoted coastal tourism and placed emphasis on the scenic benefits of the natural environment, leading to efforts to restore the ecological landscape. During the restoration of the Xinglin Bay landscape belt, a strategy of "natural succession as the primary approach, supplemented by human management" was adopted[

55]. This study focuses on the eastern coastal area of Xinglin Bay, including the boardwalk above the sea (for cycling and jogging), and the landscape belt on the east coast (with large grasslands, trails, water revetments, etc.), which spans a length of 2.6 kilometers (

Figure 1).

2.2. The research content

The study selected local residents of Xiamen City as the research subjects from all interview samples. The study focused on investigating the behaviors, physical and mental changes, and environmental perceptions of visitors. Through in-depth interviews, information such as the age of the interviewees, frequency of visits, purpose of visits, interactive behaviors with the environment, and specific physical and mental responses were collected.

After a two-week participatory observation, it was found that most visitors to the coastal area were local residents. Therefore, it was decided to select the time periods with the highest population density and conduct in-depth interviews with people present at the site. Ultimately, the study conducted semi-structured interviews during the following time periods: October 12-16, 2022, and April 8-9, 2023, from 7:00-9:00 am and 4:00-7:00 pm. The interview locations were the boardwalk above the sea and the eastern landscape belt. A total of 97 people was interviewed, with 89.7% of the total sample consisting of local residents, amounting to 87 individuals.

The interviewees from the boardwalk were categorized as Sample A, while those from the coastal area were categorized as Sample B (Table 1 Sample data and interview summary, Supplementary Materials).

2.3. Data processing

The research data were obtained from on-site interviews. The data obtained from non-structured interviews were categorized and classified in Excel according to interview time, interview location, gender, visit frequency, identity, age, behavior, visit purpose, perception type, and physical sensations. This process transformed the textual data into categorical data.

The data were then subjected to statistical analysis using contingency tables and chi-square tests to explore the relationships between different variables. The research hypothesis assumed that the two variables in the contingency table were independent, and this assumption was tested using the chi-square test. If the chi-square value is significant and the corresponding p-value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a correlation between the two variables. Conversely, if the p-value is greater than 0.05, the variables are considered independent. In the calculation of the chi-square test, it is generally recommended to have more than 80% of the expected cell frequencies greater than five to avoid inflated chi-square test results.

Under the aforementioned conditions, a larger value of X

2 (1) indicates a stronger correlation between the two variables [

56]. SPSS was used to analyze the associations between visit frequency, gender, environmental interactive behavior, and healing perception. To conduct a more precise chi-square test, the visit frequency variable was further consolidated into two categories: “Seldom” and “Visit Every week”

3. Results

3.1. The age, frequency and purpose of the interviewees

A total of 87 samples living in Xiamen were selected in this study. Among them, there were 37 males and 50 females, accounting for 42.6% and 57.4% of the total number of interviewees, respectively. According to the statistical results (

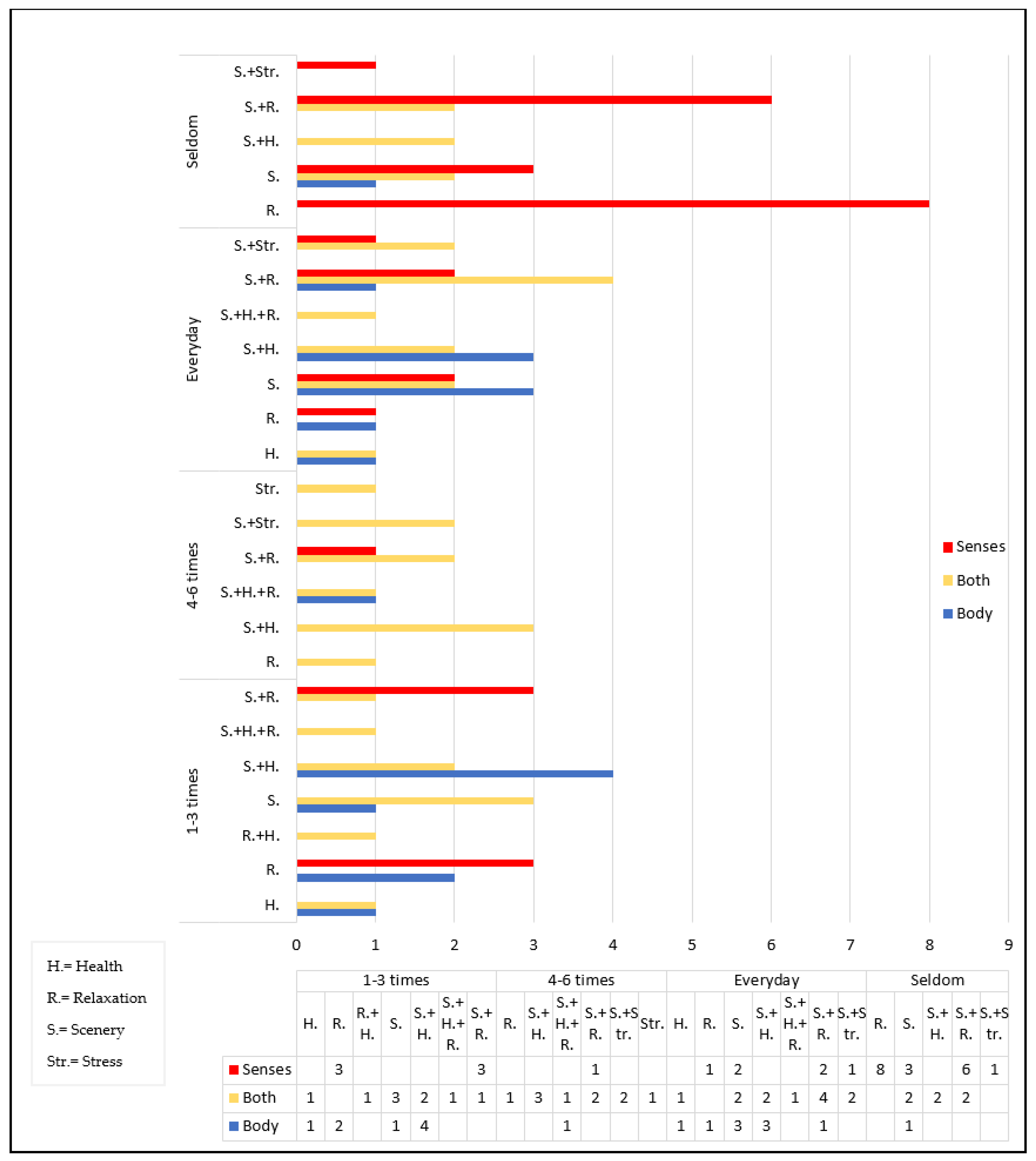

Figure 2), the data on age, frequency and purpose are described as follows:

The age range was divided into five categories: "Under 20," "20-35," "36-45," "46-65," and "Over 66". The "20-35" age group accounted for the largest proportion at 35.6%, followed by the "46-56" age group at 29%. The age groups "Under 20" and "Over 66" had the fewest visits, accounting for 4.6% and 5.7% respectively, with a combined percentage of 10.3%.

The visit frequency is categorized into four groups: “Seldom”, “1-3times/week”, “4-6times/week”, “Everyday”. Among these categories, 71.2% of the total interviewees visited the coastal zone on a weekly basis. The "Seldom" visitors accounted for 28.7% of the total interviewee. The number of interviewees visiting "Everyday" was 27, which represents 31% of the total. The categories "1-3 times/week" and "4-6 times/week" accounted for 26.4% and 13.8% of the total respectively.

The purpose of the visitors is diverse, and from the bar graph, it can be observed that the scenery is the main factor attracting people to visit. Other factors include stress, scenery, and health, all of which are reasons for visiting the coastal zone. Among them, the combination of "scenery and relaxation" has the highest proportion, accounting for 25.29% of the total interviewees, reflecting the need for people to relax both mentally and physically in the coastal zone. The proportion of visitors coming for "health" reasons accounts for 36.79% of the total interviewees (including stress factors).

3.2. Analysis of Body-Environment Interaction Behavior...s

3.2.1. Visitation frequency as a factor influencing environmental interaction

The cross-analysis table of visitation frequency and behaviors (

Table 2) shows that the frequency of "Seldom" visits is 24, accounting for 27.6% of the total, while the frequency of "Visit Every week " visits is 63, accounting for 72.4%. The behavioral engagement of the "Visit Every week " visitors is significantly higher compared to the "Seldom" visitors. Within the "Seldom" frequency range, 17 individuals engage in sensory and environmental interactions, accounting for 70.8% of the total within the "Seldom" frequency category. Among the "Visit Every week " frequency group, 31 individuals simultaneously engage in sensory and body-environment interactions, representing 49.2% of the total "Visit Every week " frequency, nearly half of the population.

Additionally, 28.5% of individuals directly engage in body-environment interactions, indicating that the high frequency of visits and the significant interaction between their bodies and the environment suggest that the coastal zone of Xinglin Bay has become an integral part of their lives.

The results indicate that there is a significant difference between visitation frequency and environmental interaction behavior, demonstrating a strong association between the two, χ2(2, N=87) =18.066, p=0(<0.05), Phi=0.46.

3.2.2. Gender does not influence spatial choices in the coastal zone

In this study, the sample size of females is higher than that of males. Therefore, the aim is to test whether gender influences the differences in perceiving the coastal zone as a daily therapeutic space.

The statistical analysis results of gender and environmental interaction behavior indicate no significant differences, χ2 (2, N=87) =3.671, p=0.160 (p>0.05), Phi=0.20. Therefore, gender does not influence the preference for the coastal zone as a daily therapeutic space.

In the female group, the number of individuals engaging in sensory and environmental interactions is 22, the number of individuals engaging in body-environment interactions is 9, and the number of individuals engaging in both sensory and body-environment interactions is 19. These numbers represent 44%, 18%, and 38% of the total female interviewees respectively (

Table 3).

In the male group, the number of individuals engaging in sensory and environmental interactions is 9, the number of individuals engaging in body-environment interactions is 10, and the number of individuals engaging in both sensory and body-environment interactions is 18. These numbers represent 24.3%, 27%, and 48.6% of the total male interviewees respectively.

These results indicate that although the proportion of female visitors to the coastal zone is higher, the proportion of males engaging in body-environment interactions is higher than that of females.

3.2.3. Differences exist in the frequency and interaction with the environment based on gender

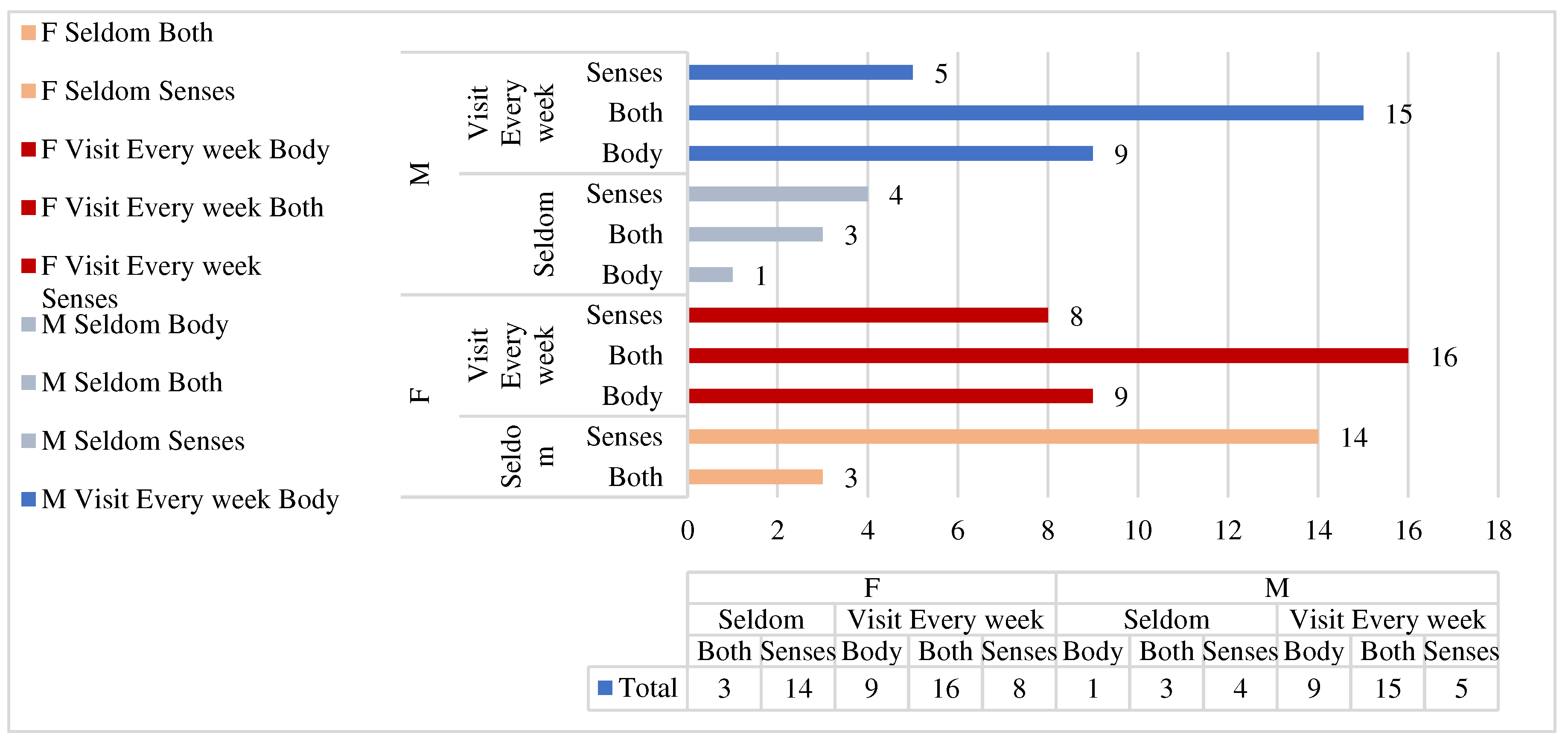

In order to further investigate the interaction behaviors between different genders and the environment, it is necessary to examine whether differences arise due to variations in visitation frequency, and to further analyze the data.

The results indicate that within the female group, in the "Seldom" visitation frequency, there were 18 individuals utilizing "Senses" interaction, and 4 individuals utilizing "Both" interactions. In the " Visit Every week " frequency, there were 9 individuals utilizing "Senses" interaction, 9 individuals utilizing "Body" interaction, and 16 individuals utilizing "Both" interactions. On the other hand, the visitation frequency distribution among males was relatively even. In the " Seldom " visitation frequency, there were 5 individuals utilizing "Senses" interaction, 3 individuals utilizing "Body" interaction, and 4 individuals utilizing "Both" interactions. In the " Visit Every week " frequency, there were 5 individuals utilizing "Senses" interaction, 9 individuals utilizing "Body" interaction, and 15 individuals utilizing "Both" interaction (

Figure 3).

The results show that there is a highly significant difference between the visitation frequency and environmental interaction behavior among females, indicating a strong association between female visitation frequency and environmental interaction,χ2(2, N=50)=13.95, p=0.001(<0.05) ,Phi=0.52. On the other hand, the data analysis results for male visitation frequency and environmental interaction behavior do not show significant differences, indicating a weaker association between male visitation frequency and environmental interaction, χ2(2, N=37)=3.824, p=0.148(p>0.05), Phi=0.32.

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that visitation frequency is an important variable that influences the interaction between individuals and the environment. The association between visitation frequency and environmental interaction behavior is affected by gender, resulting in distinct outcomes. There is a highly significant difference between female visitation frequency and environmental interaction behavior, indicating a strong correlation between the two. On the other hand, male visitation frequency and environmental interaction do not exhibit significant differences, suggesting that they are independent of each other. This suggests that females are more inclined to engage in sensory interactions with the environment, and as their visitation frequency increases, it triggers a greater level of multi-sensory and environmental interactions. However, males tend to engage in physical interactions with the environment, regardless of the frequency, as they see coastal areas as opportunities for physical activities.

3.3. Therapeutic Perception Analysi.s

3.3.1. Frequency and therapeutic perception

Among the 87 interviewees, in the "Seldom" interval, a total of 24 individuals perceived " Therapeutic Landscape", 10 individuals perceived "Mental Therapeutic" and 5 individuals perceived "Both" (

Table 4).

In the "Visit Every week " interval, there were 63 individuals, with 13 individuals perceiving " Therapeutic Landscape " and 13 individuals perceiving " Mental Therapeutic “, while 37 individuals perceived "Both".

The analysis results of visitation frequency and therapeutic perception show a highly significant difference, indicating a strong correlation between visitation frequency and environmental interaction, χ2(2, N=87)=10.033, p=0.007(<0.05), Phi=0.34.

3.3.2. The analysis of gender and therapeutic perception

Among the female visitors, the number of individuals perceiving " Therapeutic Landscape" is 13, " Mental Therapeutic" is 12, and "Both" is 27. Among the male group, the number of individuals perceiving " Therapeutic Landscape " is 12, " Mental Therapeutic" is 10, and "Both" is 16. (

Table 5). The data analysis results of gender and therapeutic perception show no significant differences, indicating a weak association between gender and therapeutic perception, χ

2 (2, N=87) =1.750,

p=0.417(>0.05)

, Phi=0.12.(

Table 5)

Based on this, it can be concluded that visitation frequency is an important variable that influences therapeutic perception, with a close correlation between the two. It can be inferred that the more frequent the visits, the greater the variety of perceived therapeutic types. On the other hand, gender and therapeutic perception are independent of each other, with a very weak correlation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Symbolic landscapes

The design theme of the Xinglin Bay coastal zone primarily focuses on the symbolic landscape of ecological restoration. It includes seven aspects: dredging and breach restoration, Intercepting sewer system, boardwalk above the sea, waterfront platforms, lawn plaza, restoration of island ecology, and landscape vegetation and resilient revetment. The aim is to promote ecological recovery in Xinglin Bay and provide increased environmental accessibility (

Table 6). The dredging and breach restoration project target the original silt accumulation in Xinglin Bay, with a focus on restoring coastal ecology. In terms of landscape healing, it can regulate water levels, improve water quality, and restore biodiversity. The Intercepting sewer system is dedicated to water quality restoration, creating a backup water source for Xiamen and alleviating water scarcity. Local residents living near Xinglin Bay are more likely to perceive the impact of these two landscape projects:

"When I was a child, my brother and I used to raise ducks here. Due to pollution, the water quality remained eutrophic, and there was often a foul smell. Now, the situation has improved a lot."

(A-13)

"In 2015, there used to be a frequent smell, but now it's barely noticeable, and the water quality is gradually improving. The air, environment, and greenery here are great. I often take walks and exercise on the boardwalk above the sea, and it feels refreshing."

(B-13)

The boardwalk above the sea connects the water's edge, relieving pressure on the waterfront while providing visitors with a space for water-related activities, sightseeing, and exercise. The waterfront platforms are constructed using corrosion-resistant granite materials and feature stepped levels, meeting people's desire for water proximity while buffering the rising water levels during high tide. The lawn plaza not only offer leisure and family spaces but also contribute to ecological restoration and increased green coverage.

The establishment of a heron ecological conservation area aims to restore island ecology. By preserving the original vegetation and planting mangroves, it stabilizes island ecology, prevents erosion, and purifies water quality. Apart from seasonal bird migrations, Xinglin Bay also hosts various bird species on a regular basis, indicating a positive trend in ecological improvement and an increasing variety of biological species.

"In spring (March to May), a large number of seabird hover around this area, especially near the boardwalk above the sea. It's a densely populated scene, even reported by China Central Television."

(B-7)

There are a lot of herons, and many people come to birdwatch on weekends.

(B-12)

4.2. Interaction between body and environment

After the completion of the dredging and Intercepting sewer systems in Xinglin Bay, the restoration of water quality has provided a waterfront area for activities. People can observe birds, enjoy sunsets, watch training sessions, and enhance their physical fitness through exercise in this area. The interaction between the body and the environment can be experienced through the boardwalk above the sea (A-7; A-27; A-34; B-12), the scent of the sea (A-43; A-55; A-59; B-7), touching the seawater (B-14), and observing migratory birds foraging along the coast (B-1; B-5; B-12; B-13).

"Due to the favorable environment, everyone enjoys running and cycling in this area. I personally make it a point to come here for exercise every day, and it has brought about significant changes in both my body and mind. The most noticeable change is the physical transformation, as I have managed to reduce my weight from 97kg to 70kg".

(B-12)

In addition to accommodating rising tides, the waterfront platform also provides a space for people to engage in water-related activities and promote interaction between parents and children. During the field research conducted for this study, it was frequently observed that children, accompanied by their parents, engaged in fishing and water play. The grassy square was filled with people enjoying picnics, flying kites, and camping. Parents often bring their children to the waterfront on weekends to enjoy outdoor activities and increase parent-child interaction, which helps to relax and improve their relationships.

"The environment here is excellent and suitable for children's activities. They enjoy playing on the grassy areas and fishing near the water's edge. This process brings about a sense of joy and relieves the pressures of daily life and work".

(B-12)

Research has shown that increasing greenery not only enhances the mental well-being of residents[

57], but also has positive effects on children's cognitive function and attention[

58].

"Before coming here, I felt very gloomy, but walking around and enjoying the scenery in this place improves my mood."

(A-57)

Local residents engage in various daily activities along the coastline, including exercising, appreciating the beautiful scenery, relaxing, contemplating life, and visiting at different times of the day, from morning to evening.

"I basically come out every morning to watch the sunrise, enjoy the flowers, listen to the birdsong, observe the herons leisurely fishing, and so on. In the evening, I also watch the sunset. The sunset here is famous, and many people come here specifically for it. The air has a high oxygen content, and being in this environment relaxes my entire mind and body."

(A-46)

Beneficial and sustained environmental changes increase the attractiveness of the environment to people. In order to relax and relieve stress, it is important to have landscape settings that incorporate natural elements, biodiversity, tranquility, and a sense of refuge[

59], However, as pointed out in the conclusion of the previous study, whether the healing green space should try to avoid social and cultural features, this study maintains a reserved attitude, because this study believes that social and cultural features should be part of daily life.

4.3. Embodied sense of place

In the coastal zone's daily activities, the interactive behaviors between the body and the environment differ significantly from those on land, thereby shaping a distinct sense of place. For example, the rowing movements while rowing on the sea (A-18; A-43; A-44; A-47; A-49). And the actions of flying and controlling a kite with the sea breeze (B-3; B-5). Rowing and flying kites are not merely physical actions but rather interactions between the body and the environment, giving rise to a sense of place. Since the external environment is the primary source of sensory information for humans, perception of the external environment primarily occurs through human senses[

60]. For instance, when rowing, one can perceive the direction of the sea currents through the tactile sensation of the oar in contact with the water. Similarly, when flying a kite, one needs to observe the direction of the sea breeze through sense of touch, hearing, and vision.

The skyline of a city and the horizon of a coastal zone indeed has significant differences. The city skyline is primarily composed of buildings or mountains, and the line of sight moves up and down due to varying heights. However, the coastline forms a horizontal line, and the horizon of the coastal zone creates a sense of expansiveness for the interviewees (A-18; A-44; B-6).

This particular group of individuals, due to their infrequent visits, primarily rely on visual, auditory, and olfactory interactions with the environment. Their visits are often driven by nostalgia, appreciation of beautiful scenery, and the desire to relax.

"In this context, every visit here evokes a sense of relaxation. The expansive vistas and favorable ecological conditions contribute to this sentiment, with a significant presence of egrets and various unfamiliar bird species".

(A-25)

Local residents, being immersed in the environment for an extended period, engage in ongoing sensory and physical interactions with their surroundings, allowing them to perceive environmental changes while experiencing physical and mental well-being. Furthermore, considering that the preferred modes of transportation for visiting the research site are bicycles and walking, it further enhances the interaction between visitors and the environment.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this article is to explore the health changes resulting from the interaction between individuals and the environment within the context of the daily therapeutic landscapes of the coastal zone. The research findings are as follows:

(1) Visitation frequency is a significant variable influencing the perception of therapeutic. There is a close correlation between the two, suggesting that a higher frequency of visits leads to a greater perception of therapeutic types.

(2) Gender does not affect the preference for selecting healing locations in the daily coastal zone, nor does it impact the perception of therapeutic.

(3) However, there are significant gender differences in visitation frequency and interactive behaviors with the environment. Female visitors exhibit a strong correlation between visitation frequency and environmental interaction, indicating a greater utilization of sensory interaction with the environment. The higher the frequency, the more it triggers multi-sensory and environmental interactions. On the other hand, male visitors show no significant difference in visitation frequency and environmental interaction. This suggests that males tend to engage in physical interaction with the environment. Regardless of high or low visitation frequency, their interaction with the coastal zone and the environment is primarily through physical movement.

In the coastal zone of Xinglin Bay, the symbolic landscape is focused on ecological restoration, particularly in terms of water quality and migratory birds, which are important indicators for local residents' identification. The improvement of water quality in the coastal zone serves as an excellent medium for the interaction between the body and the environment. Activities such as rowing and flying kites in the daily life of the coastal zone require the utilization of senses and physical engagement to experience them fully. These activities play a crucial role in generating a sense of place in the coastal zone. People generate therapeutic landscapes through their interactions with the environment, but an overemphasis on themed healing overlooks the enduring therapeutic effects of everyday landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-C. T.; methodology, S.-C. T.; software, H. W.; validation, S.-C. T., S.-H. L. and Z. Z.; formal analysis, H. W.; investigation, H. W.; resources, H. W.; data curation, H. W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-C. T. and H. W.; writing—review and editing, S.-C. T. and S.-H. L.; visualization, H. W..; supervision, S.-C. T.; project administration, Z. Z.; funding acquisition, Z. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a scientific research start-up fund of Jimei University, China, grant number Q2022014; and Undergraduate Education and Teaching Reform Research Project of Fujian Province in 2022 -- Exploration of Virtual Simulation Experiment Teaching of Tourism Landscape Design under the Background of New Liberal Arts (Project No. : FBJG20220194); and Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Research project of Jimei University in 2021 -- Research on teaching reform of environmental design graduate students based on virtual simulation experiment (YJG2105.); as well as Doctoral program of Jimei University in 2017(Q201705); The second batch of Industry-University Cooperative Education Projects of the Ministry of Education in 2021 (202102100020), and (202102391031).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was not involving humans or animals.

Acknowledgments

The study was made possible thanks to all the interviewees in the coastal zone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zeleson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landscape research. 1979, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environment and behavior. 1981, 13, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.J.; Jones, M.V.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Clark-Carter, D.; Tarvainen, M.P.; et al. Where to put your best foot forward: Psycho-physiological responses to walking in natural and urban environments. Journal of environmental psychology. 2016, 45, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: Medical issues in light of the new cultural geography. Social Science & Medicine. 1992, 34, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: Theory and a case study of Epidauros, Greece. Environ Plann D Soc Space. 1993, 11, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradson, D. Landscape, care and the relational self: Therapeutic encounters in rural England. Health & Place. 2005, 11, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Foley, R.; Houghton, F.; Maddrell, A.; Williams, A.M. From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine. 2018, 196, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Hickman, C.; Houghton, F. From therapeutic landscape to therapeutic ‘sensescape’ experiences with nature? A scoping review. Wellbeing, Space and Society. 2023, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.S. ‘I do therefore there is’: Enlivening socio-environmental theory. Environ Polit. 2009, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, P.; Ahluwalia-Lopez, G.; Waskul, D.; Gottschalk, S. Performing Taste at Wine Festivals: A Somatic Layered Account of Material Culture. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010, 16, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, J.M. Negotiating acquired spinal conditions: Recovery with/in bodily materiality and fluids. Social Science & Medicine. 2018, 211, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, D.B.; Paula, R. Vital spaces and mental health. Medical Humanities. 2019, 45, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Lee, H.-Y.; Luo, X.-Y. The effect of virtual reality forest and urban environments on physiological and psychological responses. Urban forestry & urban greening. 2018, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zabini, F.; Albanese, L.; Becheri, F.R.; Gavazzi, G.; Giganti, F.; Giovanelli, F.; et al. Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoo, K.S.; Karam, D.S.; Abdullah, M.Z. The physiological and psychosocial effects of forest therapy: A systematic review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2020, 54, 126744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Hsieh, H. Beyond restorative benefits: Evaluating the effect of forest therapy on creativity. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2020, 51, 126670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Takayama, N.; Park, B.-J.; Li, Q.; Song, C.; et al. Influence of Forest Therapy on Cardiovascular Relaxation in Young Adults. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014, 2014, 834360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.; Lee, S.; Jo, Y.; Kang, S.; Park, S.; Kang, H. The Effects of Forest Therapy on Immune Function. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Chu, Y.-C.; Kung, P.-C. Taiwan’s forest from environmental protection to well-being: The relationship between ecosystem services and health promotion. Forests. 2022, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Lin, C.-M.; Tsai, M.-J.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Effects of Short Forest Bathing Program on Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Mood States in Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2017, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-J.; Lin, F.-H.; Kuo, W.-J. The neural mechanism underpinning balance calibration between action inhibition and activation initiated by reward motivation. Scientific reports. 2017, 7, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavazzi, G.; Giovannelli, F.; Currò, T.; Mascalchi, M.; Viggiano, M.P. Contiguity of proactive and reactive inhibitory brain areas: A cognitive model based on ALE meta-analyses. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2021, 15, 2199–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, R.D. Dynamical approaches to cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2000, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zou, Z.; Tsai, S.-C. Exploring Environmental Restoration and Psychological Healing from Perspective of Resilience: A Case Study of Xinglin Bay Landscape Belt in Xiamen, China. International Journal of Environmental Sustainability and Protection. 2022, 2, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Phoenix, C.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape. Social Science & Medicine. 2015, 142, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelard, G. Water and dreams; The Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture: Dallas, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, G. The poetics of space; Beacon Press: Boston, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Game, A.; Metcalfe, A. ‘My corner of the world’: Bachelard and Bondi Beach. Emotion, Space and Society. 2011, 4, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values; The commercial press: Beijing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, E.W. The growth of Inland and seaside health resorts in England1. Scottish Geographical Magazine. 1939, 55, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.W. The Holiday Industry and Seaside Towns in England and Wales. In: Baumgartner, Heinz, (Hrsg.) LBHF, editors. Festschrift Leopold G Scheidl zum 60 Geburtstag. Wien: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne OHG; 1965. 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. Seashore-Primitive Home of Man? Proc Am Philos Soc. 1962, 106, 41–47, http://www.jstor.org/stable/985209. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A. Where land meets sea: Coastal explorations of landscape, representation and spatial experience; Routledge, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Doody, J.P. Coastal conservation and management: An ecological perspective; Springer Science & Business Media, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, R.H.; Chaineux, M.-C.P. The healing sea: A sustainable coastal ocean resource: Thalassotherapy. Journal of Coastal Research. 2009, 25, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass-Coffin, B. Discourse, daño, and healing in north coastal Peru. Medical anthropology. 1991, 13, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdtsieck, J.J. In the spirit of Uganga: Inspired healing and healership in Tanzania; AGIDS Amsterdam, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, R.; Collins, D. Feeling for the coast: The place of emotion in resistance to residential development. Social & Cultural Geography. 2012, 13, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. Therapeutic landscapes and healing gardens: A review of Chinese literature in relation to the studies in western countries. Frontiers of Architectural Research. 2014, 3, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W. Therapeutic landscapes: An evolving theme. Health & Place. 2005, 11, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K.; Hu, H.; Smit, J. Therapeutic landscapes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Increased and intensified interactions with nature. Social & Cultural Geography 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Fogel, A.; Escoffier, N.; Ho, R. Effects of COVID-19-related stay-at-home order on neuropsychophysiological response to urban spaces: Beneficial role of exposure to nature? Journal of environmental psychology. 2021, 75, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellard, S.; Bell, S.L. A fragmented sense of home: Reconfiguring therapeutic coastal encounters in Covid-19 times. Emotion, Space and Society. 2021, 40, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cui, Q.; Xu, H. Desert as therapeutic space: Cultural interpretation of embodied experience in sand therapy in Xinjiang, China. Health & Place. 2018, 53, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. Affordable and enjoyable health shopping: Commodified therapeutic landscapes for older people in China’s urban open spaces. Health & Place. 2021, 70, 102621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Grady, S.C.; Rosenberg, M.W. Creating therapeutic spaces for the public: Elderly exercisers as leaders in urban China. Urban Geography. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, X.-m. Environmental Characteristics and Changes of Coastal Ocean as Land-ocean Transitional Zone of China. Scientia Geographica Sinica 2011, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.-H.; Jiang, Y.; Lin c Li, T.-W.; Chen, F.; Wang, W.-Y. Research on the coupling coordination relationship between Xiamen Port development and coastal eco-nvironment evolution. Environmental Pollution and Prevention 2020, 890–3900. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Hu, M.-H.; Song, L.-L.; Yu, J.; Liu, R.-J.; Wang, S.-X.; et al. Coastal zone use influences the spatial distribution of microplastics in Hangzhou Bay, China. Environmental Pollution. 2020, 266, 115137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Tsai, S.-C. The Transformation of Coastal Governance Pattern from Human Ecology to Political Ecology—A Case Study of Jimei Peninsula, Xiamen, China. Preprintsorg. 2023, 2023061934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pearson, S.G. Managing China ‘ s Coastal Environment : Using a Legal and Regulatory Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development. 2015, 6, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau XOaF. Treading the Waves and Flying Songs: Oral Records of Key Figures in the Twenty Years of Comprehensive Management of the Coastal Zone in Xiamen from 1996 to 2016; Xiamen University Press: Xiamen, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, J. Xiamen: An ecological landscape belt will be built around Xinglin Bay to borrow scenery from the Garden Expo. Xiamen Daily 2010, 07/10.

- Qiu, H.-Z. Quantitative Research and Statistical Analysis SPSS<PASW> Data Analysis Paradigm Analysis; Chongqing University press: Chongqing, China, 2013; p. 386. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Aggression and Violence in the Inner City:Effects of Environment via Mental Fatigue. Environment and Behavior. 2001, 33, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M. At Home with Nature:Effects of “Greenness” on Children’s Cognitive Functioning. Environment and Behavior. 2000, 32, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Niu, Q.-C.; Zhu, L.; Gao, T.; Qiu, L. Construction of Restorative Environment Based on Eight Perceived Sensory Dimensions in Green Spaces—A Case Study of the People's Park in Baoji. Green Infrastructure 2018, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Durie, B. Doors of perception. New Scientist. 2005, 185, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).