Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Selection criteria

- (1)

- Interventions must use glucosamine as the non-combined formulation at least

- (2)

- English--written articles about cost-effectiveness analysis or any type of economic evaluation

- (3)

- Topic about osteoarthritis therapy with viable duration

- (4)

- Specific information about ICER value at least

- (5)

- Clear conclusion whether Glucosamine was cost-effective or not

- (1)

- Studies that combined Glucosamine with other compounds

- (2)

- Not available in English language

- (3)

- Not talk about osteoarthritis treatment, not focus on glucosamine

- (4)

- Not about osteoarthritis treatment

- (5)

- Unclear statement or lack informaton about ICER

2.3. Data extraction

2.4. Quality assessment of selected articles

3. Results

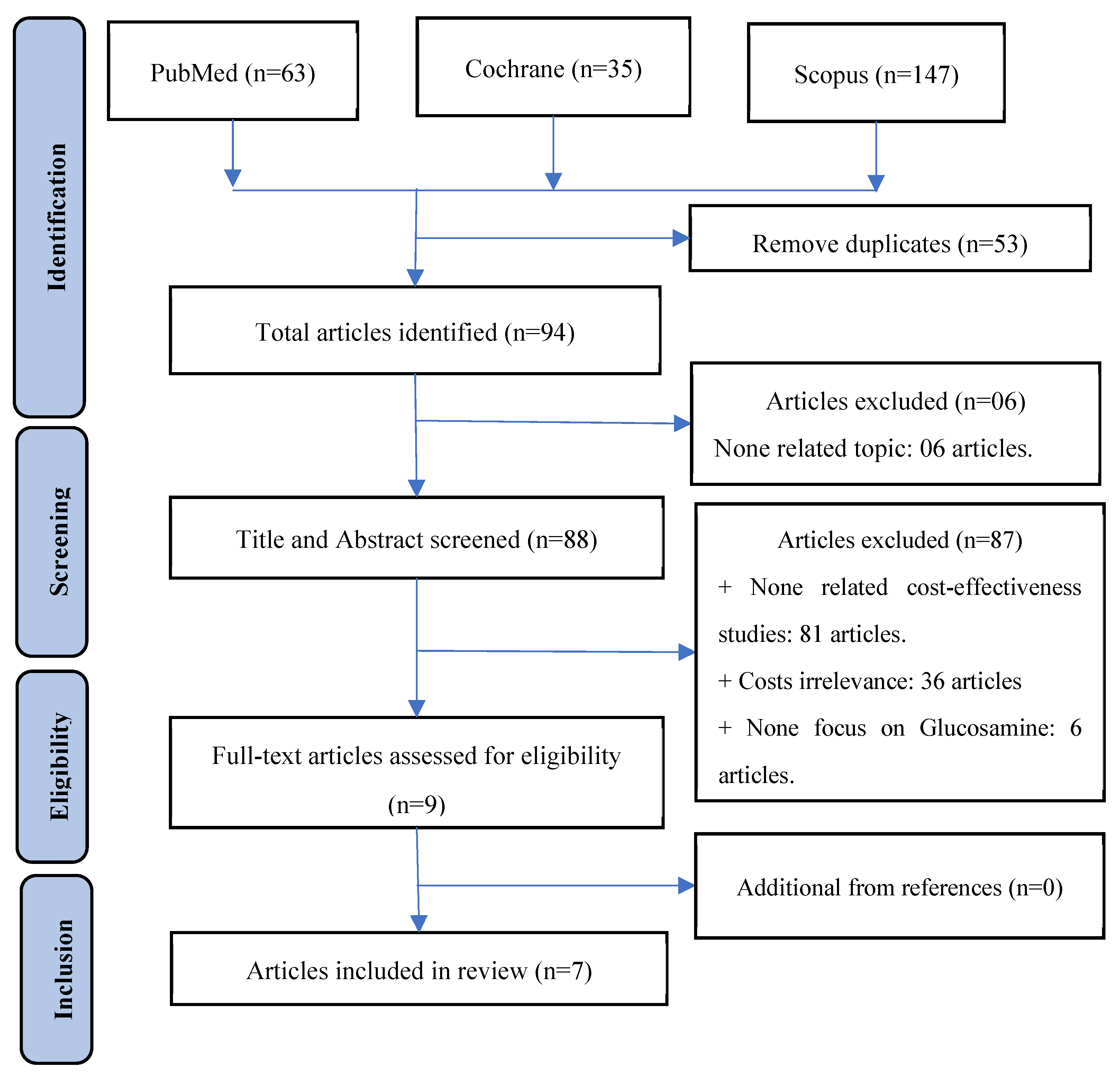

3.1. Study selection process

3.2. Characteristic of included studies

| a. Characteristic of selected studies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Study, year, and country | Subjects | Intervention | Perspective | Method | Time horizon | Costs of Glucosamine |

| 1 | Bruyère et al.[45], 2023, Thailand | OA patients | pCGS vs. OFG vs. Placebo | Healthcare | CEA | - |

$27.78/powder pCGS, $27.22/tablet pCGS. ;$14.61/powder OFG, $10.80/tablet OFG. |

| 2 | Luksameesate et al.[15], 2022, Thailand | Patients ≥ 45 years old with mild-to-moderate pain ;and no comorbidities |

pCGS combined with etoricoxib vs ;Glucosamine monotherapy |

Societal | CEA | Lifetime | - |

| 3 | Bruyère et al.[46], 2021, Germany | OA patients ;> 40 years old |

pCGS vs. OFG | Healthcare | CEA | - | - |

| 4 | Bruyère et al.[47], 2019, | OA patients ;> 40 years old |

pCGS vs. OFG | Healthcare | CEA | - | 0.9 €/day for pCGS, ;0.55 €/day for OFG |

| 5 | Scholtissen et al.[41], 2010 Spain, Portugal | Knee OA ;patients with average age 63 years old |

GS ;vs Paracetamol vs. placebo |

Healthcare | CEA | 6 months | - |

| 6 | Black et al.[48], 2009, UK | Knee OA ;patients |

GS/GH vs. chondroitin sufate vs. GS and chondroitin | National healthcare system | CEA | Lifetime | £221 (1-year) |

| 7 | Segal et al.[49], 2004, Australia | OA patients | Interventions for arthritis ;including Glucosamine |

National healthcare system | CUA | - | $180 (1-year) |

| b. Characteristic of selected studies (continue) | |||||||

| No. | Study, year, and country | Subjects | Intervention | Model type | Duration | Sensitivity analysis |

Discount ;rate |

| 1 | Bruyère et al.[45], 2023, Thailand | OA patients | pCGS vs. OFG vs. Placebo | Grootendorst ;model |

6 months | - | - |

| 2 | Luksameesate et al.[15], 2022, Thailand | Patients ≥ 45 years old with mild-to-moderate pain ;and no comorbidities |

pCGS combined with etoricoxib vs ;Glucosamine monotherapy |

Markov model | 6 months | One-way; PSA | 3% |

| 3 | Bruyère et al.[46], 2021, Germany | OA patients ;> 40 years old |

pCGS vs. OFG | Grootendorst ;model |

3 years | - | - |

| 4 | Bruyère et al.[47], 2019, | OA patients ;> 40 years old |

pCGS vs. OFG | Grootendorst ;model |

3 years | One-way | - |

| 5 | Scholtissen et al.[41], 2010 Spain, Portugal | Knee OA patients with average age 63 years old | GS vs. Paracetamol vs. placebo | Mathematical – decision model | 6 months | PSA | - |

| 6 | Black et al.[48], 2009, UK | OA patients | Interventions for OA ;including Glucosamine |

Mathematical – decision model | 1 year | - | 5% |

| 7 | Segal et al.[49], 2004, Australia | Knee OA ;patients |

GS sulphate/hydrochloride vs. chondroitin sulphate vs. GS and chondroitin | Cohort model | 1 year | One-way | 3.5% |

3.3. Quality assessment by QHES instrument

3.4. Keypoint data related to cost-effectiveness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Litwic, A.; Edwards, M.H.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull 2013, 105, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, C.W. Osteoarthritis: the cause not result of joint failure? Ann Rheum Dis 1989, 48, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020, 72, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute_for_Health_Metrics_and_Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Data Resources. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019 (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Institute_for_Health_Metrics_and_Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Osteoarthritis-level 3 cause. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/osteoarthritis-level-3-cause#:~:text=Summary%20Osteoarthritis%20(OA)%20resulted%20in,%25%20of%20OA%20YLDs%2C%20respectively (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Neogi, T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013, 21, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, M.; Bridgett, L.; March, L.; Hoy, D.; Penserga, E.; Brooks, P. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis in Asia. Int J Rheum Dis 2011, 14, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.A.; Goodman, R.A.; Holtzman, D.; Posner, S.F.; Northridge, M.E. Aging in the United States: opportunities and challenges for public health. Am J Public Health 2012, 102, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.; Doblhammer, G.; Rau, R.; Vaupel, J.W. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009, 374, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortley, D.; An, J.Y.; Heshmati, A. Tackling the Challenge of the Aging Society: Detecting and Preventing Cognitive and Physical Decline through Games and Consumer Technologies. Healthc Inform Res 2017, 23, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Kolahi, A.A.; Smith, E.; Hill, C.; Bettampadi, D.; Mansournia, M.A.; Hoy, D.; Ashrafi-Asgarabad, A.; Sepidarkish, M.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis 2020, 79, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseases, G.B.D.; Injuries, C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jordan, J.M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med 2010, 26, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luksameesate, P.; Tanavalee, A.; Taychakhoonavudh, S. An economic evaluation of knee osteoarthritis treatments in Thailand. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 926431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Hoa, T.T.; Darmawan, J.; Chen, S.L.; Van Hung, N.; Thi Nhi, C.; Ngoc An, T. Prevalence of the rheumatic diseases in urban Vietnam: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. J Rheumatol 2003, 30, 2252–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Garstang, S.V.; Stitik, T.P. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006, 85, S2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.D.; Golightly, Y.M. State of the evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015, 27, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, C.; Leyland, K.M.; Peat, G.; Cooper, C.; Arden, N.K.; Prieto-Alhambra, D. Association Between Overweight and Obesity and Risk of Clinically Diagnosed Knee, Hip, and Hand Osteoarthritis: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016, 68, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwic, A.; Edwards, M.; Dennison, E.; Cooper, C. Epidemiology and Burden of Osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull 2013, 105, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamri, N.A.A.; Harith, S.; Yusoff, N.A.M.; Hassan, N.M.; Ong, Y.Q. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Primary Prevention of Osteoarthritis in Asia: A Scoping Review. Elderly Health Journal 2019, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, J.W.; Knahr, K. Strategies for the prevention and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007, 21, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianakos, A.A.; Kontelis, L.K.; Karamitsos, D.G.; Aslanidis, S.I.; Georgountzos, A.I.; Kaziolas, G.O.; Pantelidou, K.V.; Vafiadou, E.V.; Dantis, P.C.; Group, E.S. Prevalence of symptomatic knee, hand, and hip osteoarthritis in Greece. The ESORDIG study. J Rheumatol 2006, 33, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- survey, A.N.h. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, L.; Day, S.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Osborne, R.H. Can we reduce disease burden from osteoarthritis? Med J Aust 2004, 180, S11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29-30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, L.M.; Bachmeier, C.J. Economics of osteoarthritis: a global perspective. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1997, 11, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.H.; Rat, A.C.; Sellam, J.; Michel, M.; Eschard, J.P.; Guillemin, F.; Jolly, D.; Fautrel, B. Economic impact of lower-limb osteoarthritis worldwide: a systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016, 24, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torio CM, Moore BJ. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs 2006.

- Yelin, E.; Weinstein, S.; King, T. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016, 46, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolas, I.; Woskie, L.R.; Jha, A.K. Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA 2018, 319, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pen, C.; Reygrobellet, C.; Gerentes, I. Financial cost of osteoarthritis in France. The "COART" France study. Joint Bone Spine 2005, 72, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease, C.; Prevention. Prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among adults--United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002, 51, 948–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.C.; Helmick, C.G.; Arnett, F.C.; Deyo, R.A.; Felson, D.T.; Giannini, E.H.; Heyse, S.P.; Hirsch, R.; Hochberg, M.C.; Hunder, G.G.; et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 1998, 41, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Gupte, C.; Akhtar, K.; Smith, P.; Cobb, J. The Global Economic Cost of Osteoarthritis: How the UK Compares. Arthritis 2012, 2012, 698709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz, H.; Gunnarsson, C.L.; Fang, H.; Rizzo, J.A. Osteoarthritis and absenteeism costs: evidence from US National Survey Data. J Occup Environ Med 2010, 52, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, M.C.; Altman, R.D.; April, K.T.; Benkhalti, M.; Guyatt, G.; McGowan, J.; Towheed, T.; Welch, V.; Wells, G.; Tugwell, P.; et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Nuki, G.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Abramson, S.; Altman, R.D.; Arden, N.K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.; Brandt, K.D.; Croft, P.; Doherty, M.; et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010, 18, 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Dennison, E.M.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. Inappropriate claims from non-equivalent medications in osteoarthritis: a position paper endorsed by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Aging Clin Exp Res 2018, 30, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, G. [Topical therapy of arthroses with glucosamines (Dona 200)]. Munch Med Wochenschr 1969, 111, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtissen, S.; Bruyère, O.; Neuprez, A.; Severens, J.L.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Rovati, L.; Hiligsmann, M.; Reginster, J.Y. Glucosamine sulphate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: cost-effectiveness comparison with paracetamol. Int J Clin Pract 2010, 64, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Jansma, E.P.; Riphagen, I.I.; Vet, H.C.W.d. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res 2009, 18, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Fan, K.; Yan, L.; Fan, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, P.; Yu, H.; Li, J.J.; et al. Cost Effectiveness of Pharmacological Management for Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2022, 20, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofman, J.J.; Sullivan, S.D.; Neumann, P.J.; Chiou, C.F.; Henning, J.M.; Wade, S.W.; Hay, J.W. Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm 2003, 9, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyere, O.; Detilleux, J.; Reginster, J.Y. Health Technology Assessment of Different Glucosamine Formulations and Preparations Currently Marketed in Thailand. Medicines (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Detilleux, J.; Reginster, J.Y. Cost-Effectiveness Assessment of Different Glucosamines in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Simulation Model Adapted to Germany. Curr Aging Sci 2021, 14, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Reginster, J.Y.; Honvo, G.; Detilleux, J. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of glucosamine for osteoarthritis based on simulation of individual patient data obtained from aggregated data in published studies. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019, 31, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.; Clar, C.; Henderson, R.; MacEachern, C.; McNamee, P.; Quayyum, Z.; Royle, P.; Thomas, S. The clinical effectiveness of glucosamine and chondroitin supplements in slowing or arresting progression of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2009, 13, 1–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal L, D.S., Chapman A. Segal L, D.S., Chapman A, Osborne RH. Priority setting in Osteoarthritis. 2004.

- Weinstein, M.C.; Stason, W.B. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med 1977, 296, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenschein, K.; Johannesson, M.; Yokoyama, K.K.; Freeman, P.R. Hypothetical versus real willingness to pay in the health care sector: results from a field experiment. J Health Econ 2001, 20, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Wolfe, R.; Mai, T.; Lewis, D. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of a topical cream containing glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, and camphor for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 2003, 30, 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelká, K.; Gatterová, J.; Olejarová, M.; Machacek, S.; Giacovelli, G.; Rovati, L.C. Glucosamine sulfate use and delay of progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med 2002, 162, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.D.; Wilkinson, C.L.; Pope, E.F.; Chambers, J.D.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J. The influence of time horizon on results of cost-effectiveness analyses. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2017, 17, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, H.; Hashiguchi, M.; Hori, S. Estimating the range of incremental cost-effectiveness thresholds for healthcare based on willingness to pay and GDP per capita: A systematic review. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, M.Y.; Lauer, J.A.; De Joncheere, K.; Edejer, T.; Hutubessy, R.; Kieny, M.P.; Hill, S.R. Cost-effectiveness thresholds: pros and cons. Bull World Health Organ 2016, 94, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ii M IA, Nakamura R. Considering the costs and benefits of medical care (In Japanese). 2019.

- Bai-dang, Z.; Zu-jian, L.; Huan-tian, Z.; Ming-tao, H.; Dong-sheng, L. Cost-effectiveness analysis on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis by glucosamine hydrochloride and glucosamine sulfate. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2012, 16, 9867–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years | 2004 | 2009 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of articles | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Drugs used | Glucosamine and OTC drugs (NSAIDs, Paracetamol) | Glucosamine | ||||||

| Number of ;articles |

3 | 4 | ||||||

| Type of ;Glucosamine |

pCGS | pCGS and OFG | ||||||

| Number of ;articles |

3 | 4 | ||||||

| OA site | Knee | All | ||||||

| Number of ;articles |

5 | 2 | ||||||

| No. | Study, year, and country | Comparator | Cost | QALY gain | ICER | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bruyère et al.[45], 2023, Thailand | pCGS vs. OFG | At 3 months ;pCGS: $53.805 ;OFG: $100.44At 6 months ;pCGS: $126.1359 ; |

At 3 months ;pCGS: 0.017 ;OFG: 0.0031At 6 months ;pCGS: 0.0411 ;OFG: 0.0048 |

At 3 months ;pCGS/PBO: 3165 USD/QALYOFG/PBO: 32,400 USD/QALY ;At 6 months ;pCGS/PBO: 3069 USD/QALY ;OFG/PBO: placebo better |

pCGS is cost-effective at threshold 3260 USD/QALY ;pCGS is more cost-effective than OFG |

| 2 | Luksameesate et al.[15], 2022, Thailand | pCGS + standard care vs. standard care | - | 0.87 | Dominant | The early addition of pCGS into standard care treatment early is cost-saving and more effective compared to standard care alone |

| 3 | Bruyère et al.[46], 2021, Germany | pCGS vs. OFG | At 3 months ;pCGS: €77.0964 ;OFG: €208.854At 6 months ;pCGS: €183.0003 ;At 36 months ;pCGS: €2785.2712 |

At 3 months ;pCGS: 0.0164 ;OFG: 0.0036At 6 months ;pCGS: 0.0413 ;OFG: 0.0044 ;At 36 months ;pCGS: 0.2701 |

At 3 months ;pCGS/PBO: 4,701 €/QALY ;OFG/PBO: 58,015 €/QALY ;At 6 months ;pCGS/PBO: 4,431 €/QALY ;OFG/PBO: Placebo better ;At 36 months ;pCGS/PBO: 10,312 €/QALY |

pCGS is more cost-effective than OFG. |

| 4 | Bruyère et al.[47], 2019, | pCGS vs. OFG | At 3 month ;pCGS: €90.234 ;OFG: €151.009 ;At 6 months ;pCGS: €209.413 ;At 36 monthpCGS: €3162.910 |

At 3 month ;pCGS: 0.0169 ;OFG: 0.00303 ;At 6 months ;pCGS :0.0435 ;OFG: 0.00424 ;At 36 months ;pCGS: 0.2742 ; |

At 3 month ;pCGS/PBO: 5347.2 €/QALY ;OFG/PBO: 49737.4 €/QALY ;At 6 months ;pCGS/PBO: 4807.2 €/QALY ;OFG/PBO: Placebo betterAt 36 monthpCGS/PBO: 11535.5 €/QALY |

pCGS is more cost-effective than OFG. |

| 5 | Scholtissen et al.[41], 2010 ;Spain, Portugal |

GS vs. Paracetamol, ;GS vs. Placebo |

- | - | GS/Paracetamol: ;-1376 €/QALY ;GS/Placebo: ;3617.47 €/QALY |

GS is a highly cost-effective vs. Paracetamol |

| 6 | Black et al.[48], 2009, UK | GS adding conventional vs. conventional care | £2,346.85 | 0.11 | 21,335£/QALY | Addition of GS therapy to current care is cost-effective at threshold 22,000£/QALY |

| 7 | Segal et al.[49], 2004, Australia | GS vs. NSAIDs | $180.024 | 0.052 | 3462 $/QALY | Glucosamine is cost-effective |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).