Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

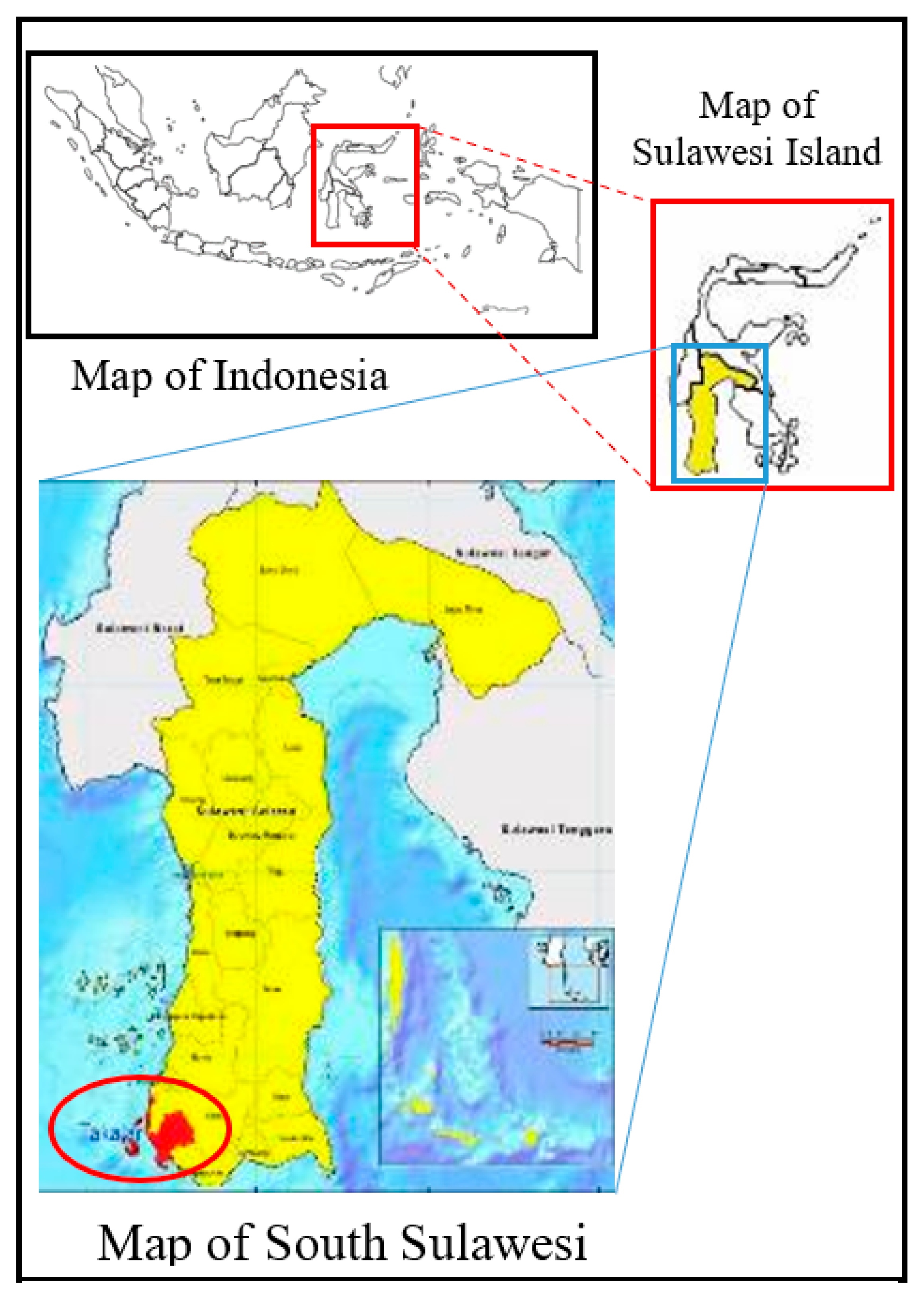

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

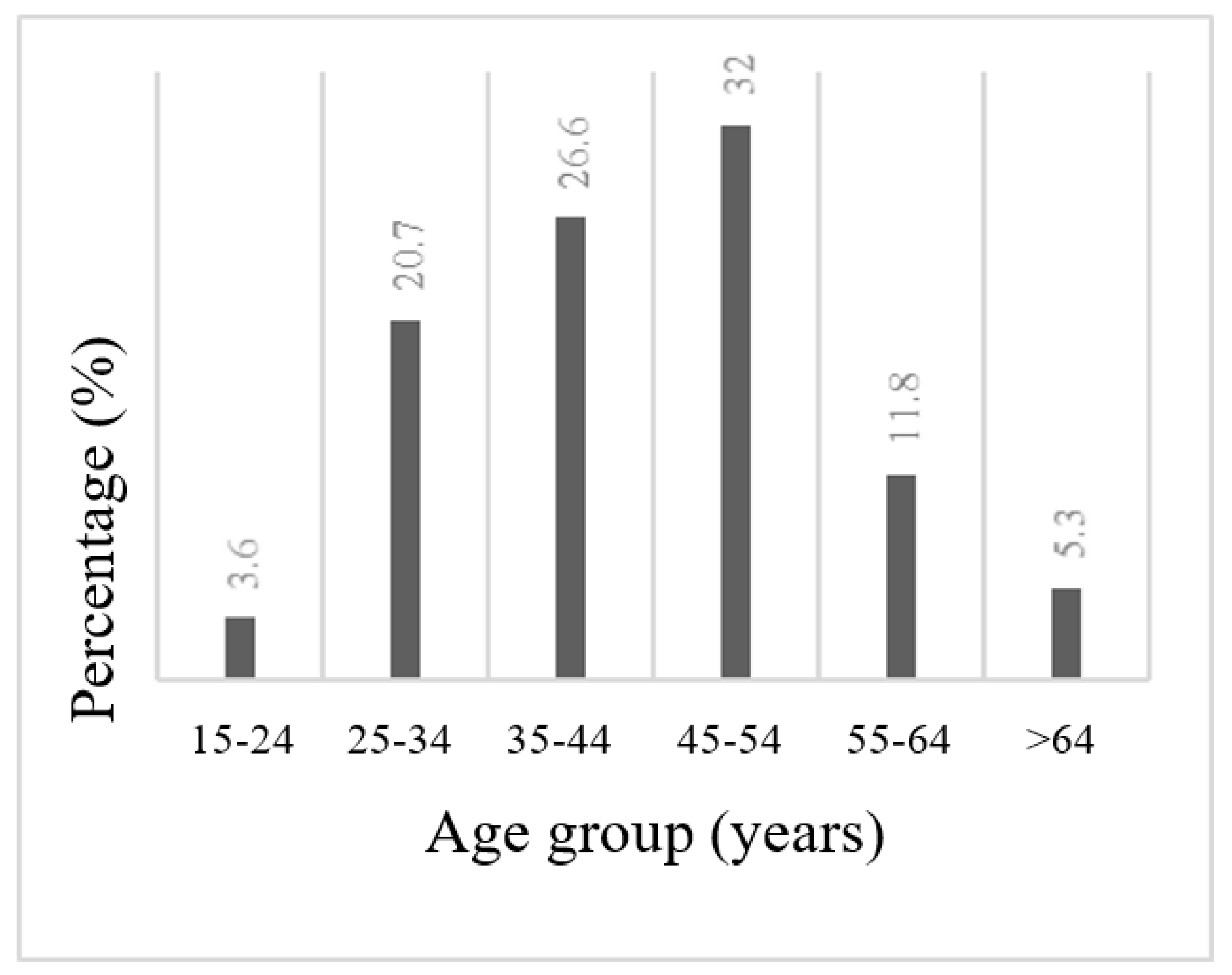

3.1. Characteristics of fishers’ household

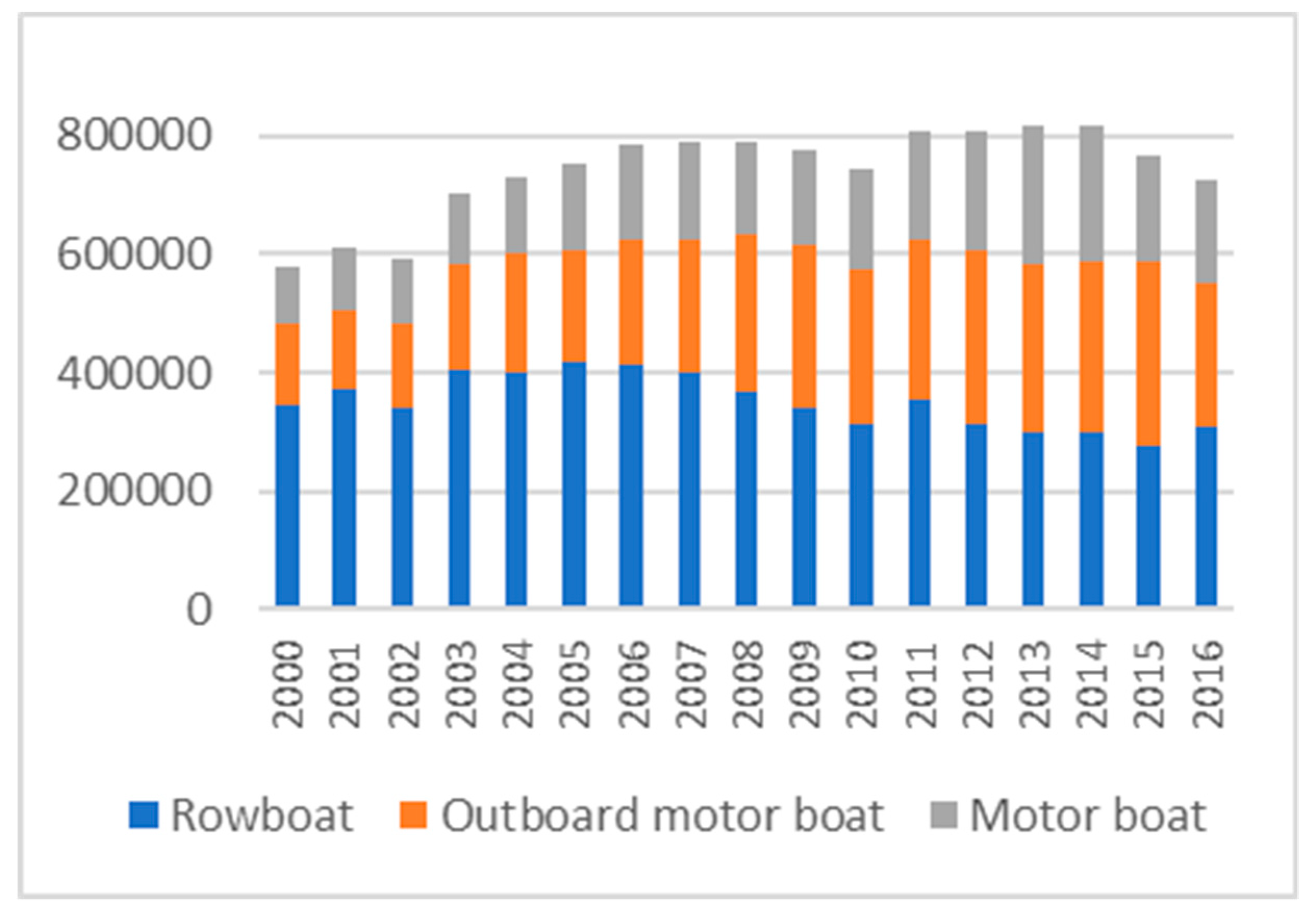

3.2. Fishers’ boat and fishing tools

3.3. Fishers’ primary and secondary income

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MMAFI, 2016. Konsumsi Ikan Naik dalam 5 Tahun Terakhir Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan. Available at: http://kkp.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Konsumsi-Ikan-Naik-dalam-5-Tahun-Terakhir.pdf Accessed on 13 March 2017.

- Tajerin, Yusuf, R., Sastrawidjaja, and Asnawi, 2007. Keterkaitan Sektor Perikanan Dalam Perekonomian Indonesia: Pendekatan Model Input-Output. J. Bijak dan Riset Sosek KP, 2(1).

- Winter, G. (Ed)., 2009. Towards Sustainable Fisheries Law. A Comparative Analysis. Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- FAO, 2018. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Martins, I. M., Medeiros, R.P., Domenico, M.D. and Hanazaki, N., 2018. What Fishers’ Local Ecological Knowledge Can Reveal about the Changes in Exploited Fish Catches. Fisheries Research, 198, pp.109-116.

- FAO, 2008. Achieving Poverty Reduction Through Responsible Fisheries. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Akbarsyah, N., Wiyono, E. S., and Solihin, I., 2017. Dependency and Perception of Handline Fishermen towards Fish Resources at Prigi Trenggalek East Java. Marine Fisheries, 8(2), pp. 199-210.

- Setiawan, I., 2008. Keragaan Pembangunan Perikanan Tangkap: Suatu Analisis Program Pemberdayaan Nelayan Kecil. Indonesia. Bogor Agricultural University (Unpublished). Available at: https://repository.ipb.ac.id/handle/123456789/41045 (Accessed: 17 August 2021).

- Salam, M., 2005. Poverty Structure in Indonesian Forest Area: A Comparative Study on Poverty Structural Causal Model of Forest and Non-Forest Communities. Japan: Ryukoku University (Unpublished).

- Hafsaridewi, R., Fahrudin, A., Sulistiono, Sutrisno, D., and Koesshendrajana, S., 2018. Fishers’ Resilience to the Availability of Fishery Resources in Karimunjawa Island. Journal of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, 9(2), pp. 527-540. [CrossRef]

- Bene, C., 2003. When Fishery Rhymes with Poverty: A first Step Beyond the Old Paradigm on Poverty in Small-scale Fisheries. World Development, 31(6), pp.949-975. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Agency of Indonesia, 2021. Jumlah Perahu/Kapal Menurut Provinsi dan Jenis Perahu /Kapal, 2000-2016. Available at: https://www.bps.go.id/statictable/2014/01/10/1710/jumlah-perahu-kapal-menurut-provinsi-dan-jenis-perahu-kapal-2000-2016.html (Accessed: 2 September 2021).

- MMAFI, 2017. Laporan Tahunan Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan Tahun 2017. Indonesia: Tahunan Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan Tahun Republik Indonesia.

- Statistics Agency of South Sulawesi Province, 2021. Jumlah Rumah Tangga Perikanan Tangkap 2014-2015. Available at: https://sulsel.bps.go.id/indicator/56/980/1/jumlah-rumah-tangga-perikanan-tangkap.html (Accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Statistics Agency of Takalar District, 2016. Kabupaten Takalar Dalam Angka 2016. Indonesia: Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Takalar.

- Statistics Agency of Takalar District, 2018. Kabupaten Takalar Dalam Angka 2018. Indonesia: Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Takalar.

- Indonesian Constitution, 2019. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 45 Tahun 2009 Available at: https://pelayanan.jakarta.go.id/download/regulasi/undang-undang-nomor-45-tahun-2009-tentang-perikanan.pdf (Accessed: 4 April 2019).

- Statistics Agency of South Sulawesi Province (2018a). Education. Available at: https://sulsel.bps.go.id/subject/28/pendidikan.html#subjekViewTab3 (Accessed: 15 November 2018).

- MMAFI, 2019. Peluang Usaha dan Investasi Rumput Laut. Indonesia: Ditjen Penguatan Daya Saing Produk kelautan dan Perikanan, Kementrian Kelautan dan Perikanan Republik Indonesia.

- MAFDSS, 2017. Komoditas Unggulan Rumput Laut. Available at: http://panel. sulselprov.go.id/pages/komoditas-unggulan-rumput-laut (Accessed on 18 January 2022).

| Type | Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing ground | Driving force | Size and price | |

| Rowboat (RB)* |

Shore (0-5 km) Single day fishing |

Manpower (paddle) | Length is 2-4 meter, width is 50-75 cm Rp. 700,000 – Rp. 2,000,000 or US $ 51 – $ 145** |

| |||

| Outboard Motor Boat (OMB)* |

Off-shore (0-20 km) Single day fishing |

Single motor (can be removed or installed outside of boat before going to catch fish) |

Length is 3-7 meter, width 75-100 cm Rp. 8,000,000 – Rp. 15,000,000 or US $ 581 – $ 1,089** |

| |||

| Motor Boat (MB)* |

Off-Shore (More than 20 km), Multi-day fishing |

Single/ double motor (installed permanently inside the boat) |

Length is 10–15 meter, width 100-200cm Rp. 50,000,000 – Rp. 100,000,000 or US $ 3,630 - $ 7,261** |

| |||

| Category | Type of boat based on the category* | No. of Fisher | % | Household member (people) |

Age (years) |

School period (years) |

Experience in fishing (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MB + OMB | 5 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 45.4 | 7.2 | 23.8 |

| 2 | MB + RB | 6 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 42.0 | 5.0 | 23.7 |

| 3 | MB | 38 | 25.0 | 4.1 | 41.2 | 6.4 | 16.5 |

| 4 | OMB + RB | 7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 44.3 | 5.7 | 19.9 |

| 5 | OMB | 88 | 57.3 | 4.5 | 45.1 | 5.1 | 24.8 |

| 6 | RB | 8 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 45.1 | 3.75 | 18.0 |

| Average in total | 4.2 | 43.9 | 5.5 | 22.1 | |||

| Category | Fishing day/ month |

Sea fish catch/ month (kg) |

Selling place | Fishing ground (km) | Selling price/kg (rupiah) |

Average revenue | Variable cost | Fix Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (thousand Rp./month) | ||||||||

| 1 | 24.8 | 258.0 | Local market and city market | 45.2 | 40,000 | 8,017 | 2,951 | 2,798 |

| 2 | 22.7 | 195.3 | Shore and road side | 23.6 | 45,416 | |||

| 3 | 21.6 | 128.4 | Road side and local market | 19.6 | 43,842 | |||

| 4 | 21.7 | 178.6 | Home, shore and road side | 18.4 | 30,071 | 4,194 | 1,214 | 1,436 |

| 5 | 20.8 | 144.6 | Road side and local market | 11.4 | 47,579 | |||

| 6 | 25.5 | 174.5 | Home and shore | 7.3 | 14,875 | 2,100 | 1,027 | 0 |

| Average | 21.5 | 149.4 | 20.9 | 43,782 | 5,317 | 1,759 | 1,795 | |

| Variable | Description | Measurement | Coefficient | t Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Intercept term | -270844.2 | -0.227 | |

| Age | Fishers’ age | Years | 5197.9 | 0.320 |

| School period | Formal school period attended by fishers | Years | -10766.7 | -0.247 |

| Fishing experience | Fishers’ fishing experience or how long they have been a fisher | Years | -2916.8 | -0.186 |

| Household members | Number of household member living in the same house including the fishers themselves | People | -21283.7 | -0.190 |

| Fishing days | Number of days spend for fishing in a month | Days | 49810.6 | 2.245* |

| Boat category | Boat ownership category (Table 2) | Categorical data (1-6) | -408624.9 | -2.859* |

| Sea fish catch | Number of fish catch by fishers in a month | Kg | 15888.2 | 8.670** |

| Fish selling price | Selling price of fish per kilogram | Rupiah | 37.3 | 5.552** |

| Fishing ground | Distance from the shore to the fishing ground | Km | 4052.5 | 0.241 |

| Total net | Total number of net or catching tools possess by fishers | Nets | 180.5 | 0.127 |

| Fix cost | Fix cost spends by fishers for fishing activity in a month | Rupiah | -1.297 | -0.845 |

| Variable cost | Variable cost spends by fishers for fishing activity in a month | Rupiah | -0.4 | -2.424* |

| Second job | Availability of second job of fishers | Dummy (0=No, 1=Yes) | 1710017.0 | 5.501** |

| Net income | Total fishers’ primary job and secondary job incomes minus variable cost and fix cost | |||

| N | 98 | |||

| R2 | 0.652 | |||

| Adj-R2 | 0.598 | |||

| F- value | 12.081 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).