Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

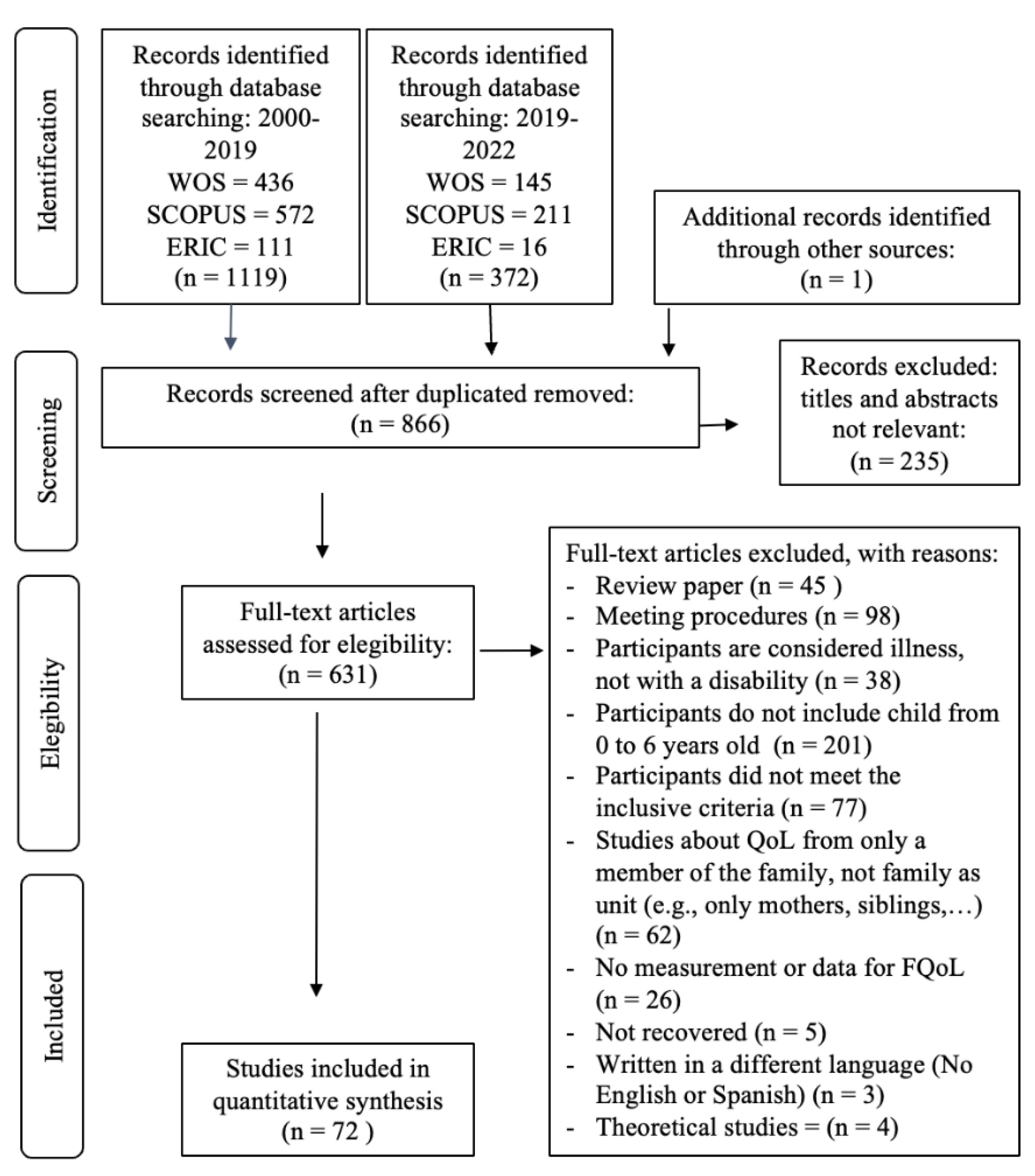

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. What is the profile of participants in FQoL research during the 0-6 years stage?

- The first group comprised a single study by Vanderkerken et al. [24], which stands out for having utilized a systemic design representing all three subsystems: spousal, parental, and sibling. This study included 49 parental dyads, one father, 12 mothers, 10 children with disabilities, and 14 siblings, with a total of 135 participants from a sample of 63 family units (nF 63 < nP 135). The authors stated, “In addition, we went beyond parents' perceptions by also taking into account the views of children (with and without disability) on FQoL and by comparing parents' and children's views on FQoL” (p. 782).

- The second group consisted of five studies that investigated FQoL from the perspective of both fathers and mothers. These studies were grouped together because the number of families was smaller than the number of participating relatives (nF < nP). Four of these studies adopted a parental subsystemic approach. Vanderkerken et al. [91] examined 34 parental dyads and argued that "members of the same family had different opinions regarding FQoL, which supports the idea of including every family member's opinion when evaluating the complex reality of quality of life in families" (p. 13). This systemic approach examines FQoL from the standpoint of the members of the parental subsystem. Similar approaches can be found in the studies by McStay et al. [89], Demchick et al. [92], and Mello et al. [90]. The fifth study in this group was by Wang et al. [23], which compared the individual perspectives of fathers and mothers. While providing information on the parental subsystem, the purpose of the study was to "test whether mothers and fathers similarly view the conceptual model" (p. 977).

- The third group comprised a study by Moyson and Roeyers [93], which approached the assessment of QoL from the experiences of siblings, concluding that siblings may define their QoL differently from their parents. Based on the data analysis, only 5.47 % of the reviewed studies adopted a systemic or sub-systemic approach. These approaches were characterized by a detailed profiling of each participant’s position within the family system and an assessment of their respective perceptions in relation to those of other family members. Rather than assessing their knowledge, these studies focused on their roles as fathers or mothers, sons or daughters, brothers or sisters, grandfathers or grandmothers, or other family members. Participants’ gender identity and their dynamic interactions with other members of the family unit were considered key elements. Vanderkerken et al. [24] pointed out the primary strength of the systemic approach by stating, "Discussing and examining differences of opinion can be a valuable approach to generate a nuanced picture of life in a family" (p. 750).

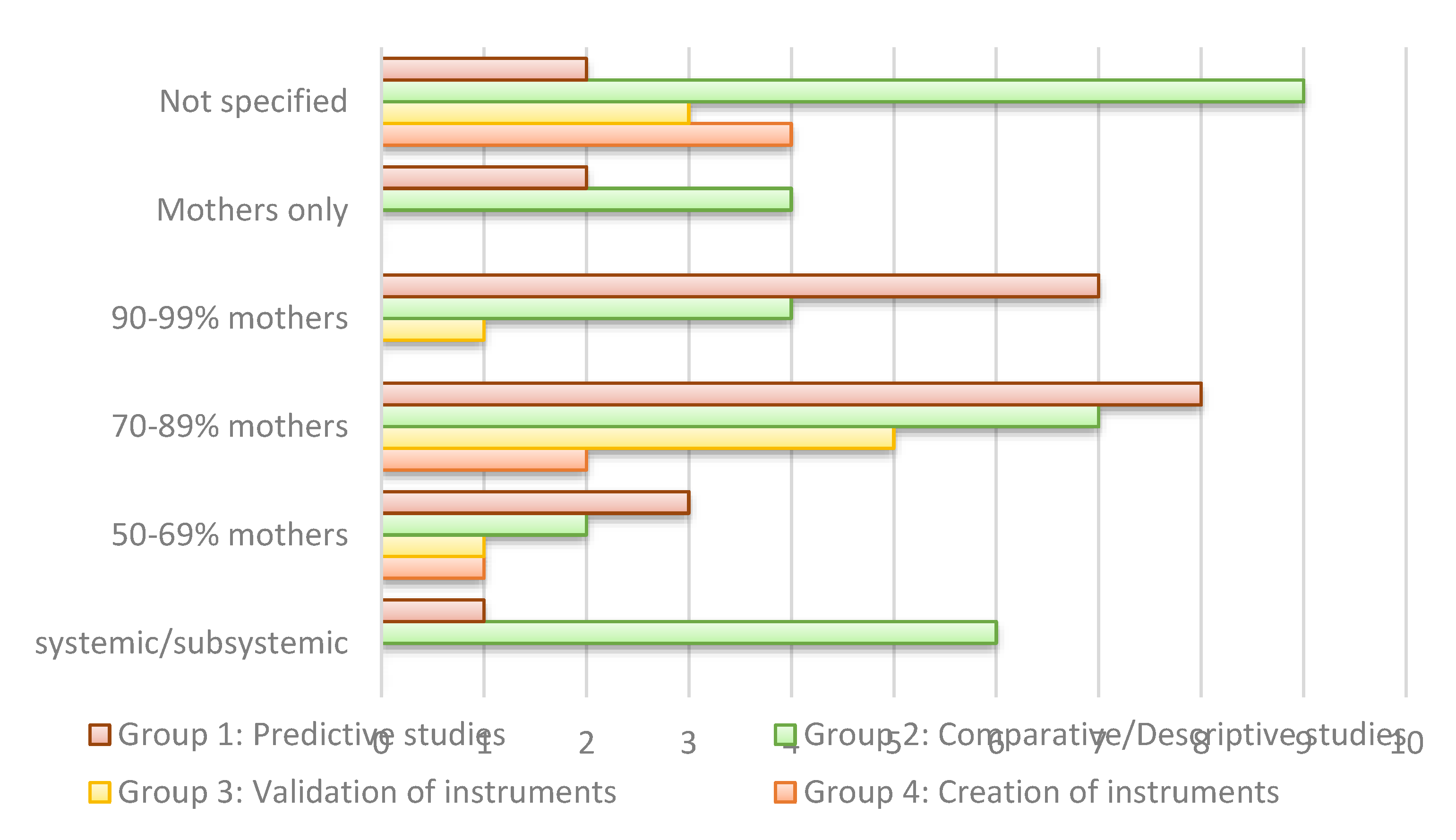

3.2. Are there differences in the profiles of participants according to the research objective?

3.3. If any biases or limitations are identified, what perspectives do researchers provide in response?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study objective | Authors |

| Creation of instruments |

Barnard et al. [45]; Brown et al. [22]; García Grau et al. [76]; Giné et al. [77]; Hoffman et al. [43]; Huang et al. [27]; Leadbitter et al. [79] |

| Validation of instruments |

Chiu et al., [35]; Chiu et al., [42]; Garcia Grau et al. [75]; Lei et al. [80]; Perry e Isaacs [84]; Rivard et al. [25]; Samuel et al. [61]; Samuel et al. [51]; Verdugo et al. [34]; Waschl et al. [36] |

| Comparative/ Descriptive |

Algood and Davis [44]; Balcells-Balcells et al. [46]; Bello-Escamilla et al. [72]; Brown et al. [73]; Clark et al. [66]; Córdoba et al. [33]; Demchick et al. [92]; Escorcia Mora et al. [37]; García Grau et al. [74]; Giné et al. [38]; Holloway et al. [67]; Jackson et al., [57]; Lee et al. [82]; Mas et al., [28]; McStay et al. [68]; McStay et al. [89]; Mello et al. [90]; Moyson et Roeyers [93]; Neikrug et al. [83]; Rillotta et al. [54]; Rodrigues et al. [70]; Schertz et al. [53]; Schlebusch et al. [31]; Steel et al. [61]; Tait and Husain [85]; Tejada-Ortigosa et al. [86]; Valverde y Jurdi [70]; Vanderkerken et al. [91]; Verger et al. [87]; Wang et al. [23] |

| Predictive |

Balcells-Balcells et al. [39]; Balcells-Balcells et al., [40]; Bhopti et al. [41]; Boehm y Carter [50]; Cohen et al. [66]; Davis y Gavidia Payne [63]; Epley et al. [62]; Eskow et al. [47]; Feng et al. [26]; Hielkema et al. [78]; Hsiao et al. [48]; Hsiao et al. [49]; Kyzar et al. [55]; Kyzar et al. [56]; Levinger et al. [29]; Liu et al. [81]; Meral et al. [69]; Samuel et al. [58]; Schlebusch et al. [30]; Summers et al. [64]; Susanto et al. [59]; Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir [32]; Taub y Werner [58]; Vanderkerken et al. [24]; Wang et al. [88] |

| Source: own elaboration. |

References

- Mandak, K., O’Neill, T., Light J., y Fosco, G. Bridging the gap from values to actions: a family systems framework for family-centered AAC services. Augmentative And Alternative Communication 2017. [CrossRef]

- Verger, S., Riquelme, I., Bagur, S., & Paz-Lourido, B. Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Families Participating in Two Different Early Intervention Models in the Same Context: A Mixed Methods Study. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Parrilla, A. Ética para una investigación inclusiva. Revista Educación Inclusiva 2010 3(1), 165-174. https://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/218.

- Nind, M. Participatory Data Analysis: A Step Too Far? Qualitative Research 2011 11(4), 349-363. [CrossRef]

- Passmore, S., Kisicki, A., Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A., Green-Harris, A. and Edwards, D. “There’s not much we can do…” researcher-level barriers to the inclusion of underrepresented participants in translational research, Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2021 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. Foreword: narrative’s moment, en M. Andrew - S. Sclater -C. Squire - A. Treacher (Eds.), Lines of narrative, Routledge, London, 2003.

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Bruner’s Narrative Turn: The Impact of Cultural Psychology in Catalonia. In Marsico, G. (ed). Jerome S. Bruner beyond 100. Cultivating posibilities, Salerno, 2015, 117-112. [CrossRef]

- González Monteagudo, J. Jerome Bruner and the challenges of the narrative turn. Narrative Inquiry 2011 21(2), 295–302. [CrossRef]

- González-Monteagudo, J. y Ochoa Palomo, C. El giro narrativo en España. Investigación y formación con enfoques autobiográficos. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa 2014 19/62, 809-829. https://core.ac.uk/reader/157763950.

- Scabini, E., & Iafrate, R. Psicologia dei legami familiari. Il Mulino: Bologna, 2019.

- Llorente, C., Revuelta, G. y Carrió, M. Characteristics of Spanish citizen participation practices in science. Journal of Science Communication 2020, 20(04), 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, V., Parra, B., Durán, P., & Magaña-González, C.R. [Re]pensemos la participación de las familias: Diagnóstico y propuestas de intervención en los servicios de atención básica a las personas en la ciudad de Barcelona. Pedagogia y Treball Social. Revista de Ciències Socials Aplicades 2021, 3-20.

- ECSA (European Citizen Science Association). Ten Principles of Citizen Science. Berlin, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A. P.; Summers, J. A.; Lee, S.-H.; Kyzar, K. Conceptualization and measurement of family outcomes associated with families of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13 (4), 346–356. [CrossRef]

- Zuna, N.; Summers, J. A.; Turnbull, A. P.; Hu, X.; Xu, S. Theorizing about family quality of life. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: From Theory to Practice; Kober, R., Ed., 2010; Vol. 41, pp 241–278.

- Gardiner, E.; Iarocci, G. Family Quality of Life and ASD: The role of child adaptive functioning and behavior problems. Autism Res. 2015, 8 (2), 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Fernández González, A.; Montero Centeno, D.; Martínez Rueda, N.; Orcasitas García, J. R.; Villaescusa Peral, M. Calidad de Vida Familiar: marco de referencia, evaluación e intervención, Siglo Cero, vol. 46 (2), 254, 2015, abril-junio, pp. 7-29. [CrossRef]

- Francisco Mora, C., Ibáñez, A., Balcells-Balcells, A. State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 7220. [CrossRef]

- Poston, D., Turnbull, A., Park, J., Mannan, H., Marquis, J., & Wang, M. Family Quality of Life: A Qualitative Inquiry. Mental Retardation 2003, 41(5), 313–328. [CrossRef]

- Roth, D., & Brown, I. Social and Cultural Considerations in Family Quality of Life: Jewish and Arab Israeli Families’ Child-Raising Experiences. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 2017, 14(1), 68-77. [CrossRef]

- Moher, E. y Liberati, A. Revisiones Sistemáticas y Metaanálisis: La responsabilidad de Los Autores, Revisores, Editores y Patrocinadores. Medicina Clínica 2010, 135, 505–506. [CrossRef]

- Brown, I., Brown, R.I., Baum, N.T., Isaacs, B.J., Myerscough, T., Neikrug, S., & Wang, M. Family Quality Life Survey: Main Caregivers of People with Intellectual or Development Disabilities, Toronto, Canadá: Surrey Place Centre. 2006. http://www.surreyplace.ca/documents/FQLS%20Files/FQOLS-2006%20General%20Version%20Aug%2009.pdf.

- Wang, M., Summers, J. A., Little, T., Turnbull, A., Poston, D., & Mannan, H. Perspectives of fathers and mothers of children in early intervention programs in assessing family quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2006, 50(12), 977–988. [CrossRef]

- Vanderkerken, L., Heyvaert, M., Onghena, P., & Maes, B. Quality of Life in Flemish Families with a Child with an Intellectual Disability: a Multilevel Study on Opinions of Family Members and the Impact of Family Member and Family Characteristics. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2018, 13(3), 779–802. [CrossRef]

- Rivard, M., Mercier, C., Mestari, Z., Terroux, A., Mello, C., & Bégin, J. Psychometric properties of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life in French-speaking families with a preschool-aged child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2017, 122(5), 439–452. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Zhou, X., Qin, X., Cai, G., Lin, Y., Pang, Y., … Zhang, L. Parental self-efficacy and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in China: The possible mediating role of social support. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2021, 63, 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., Shen, R. y Su, S., (2020) The factor structure and psychometric properties of the Family Quality of Life for Children with Disabilities in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1585. [CrossRef]

- Mas, J. M., Baqués, N., Balcells-Balcells, A., Dalmau, M., Giné, C., Gràcia, M., & Vilaseca, R. Family Quality of Life for Families in Early Intervention in Spain. Journal of Early Intervention 2016, 38(1), 59–74. [CrossRef]

- Levinger, M.; Alhuzail, N. A. Bedouin hearing parents of children with hearing loss: Stress, coping, and Quality of Life. Am. Ann. Deaf 2018, 163 (3), 328–355. [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, L.; Samuels, A. E.; Dada, S. South african families raising children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Relationship between family routines, cognitive appraisal and Family Quality of Life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60 (5), 412–423. [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, L.; Dada, S.; Samuels, A. E. Family Quality of Life of south african families raising children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47 (7), 1966–1977. [CrossRef]

- Svavarsdottir, E. K.; Tryggvadottir, G. B. Predictors of Quality of Life for families of children and adolescents with severe physical illnesses who are receiving hospital-based care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019. 33 (3), 698-705 . [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Andrade, L.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Verdugo-Alonso, M. A. Family Quality of Life of people with disability: A comparative analyses. Univ. Psychol. 2008, 7 (2), 369–383.

- Verdugo, M. A.; Cordoba, L.; Gomez, J. Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Family Quality of Life Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 794–798. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. Y.; Seo, H.; Turnbull, A. P.; Summers, J. A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of a family quality of life scale for taiwanese families of children with intellectual disability/developmental delay. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 55 (2), 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Waschl, N.; Xie, H.; Chen, M.; Poon, K. K. Construct, Convergent, and Discriminant Validity of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale for Singapore. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32 (3), 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Escorcia Mora, C.T.; García-Sánchez, F.A., Sánchez-López, M.C., Orcajada, N y Hernández-Pérez, E. Prácticas de intervención en la primera infancia en el sureste de España: Perspectiva de profesionales y familias. Anales de psicología/ annals of psychology 2018, vol. 34, nº 3, 500-509. [CrossRef]

- Giné, C., Gràcia, M., Vilaseca, R., Salvador Beltran, F., Balcells-Balcells, A., Dalmau Montalà, M., et al. Family Quality of Life for people with intellectual disabilities in Catalonia. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil., 2015, 12 (4), 244–254. [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Giné, C.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J. A. Family Quality of Life: Adaptation to spanish population of several family support questionnaires. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55 (12), 1151–1163. [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Gine, C.; Guardia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J. A.; Mas, J. M. Impact of supports and partnership on Family Quality of Life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Bhopti, A.; Brown, T.; Lentin, P. Family Quality of Life: A Key Outcome in Early Childhood Intervention ServicesA Scoping Review. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38 (4), 191–211. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-J.; Chen, P.-T.; Chou, Y.-T.; Chien, L.-Y. The mandarin chinese version of the Beach Centre Family Quality of Life Scale: Development and psychometric properties in taiwanese families of children with developmental delay. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61 (4), 373–384. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Poston, D.; Summers, J. A.; Turnbull, A. Assessing Family Outcomes: Psychometric Evaluation of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68 (4), 1069–1083. [CrossRef]

- Algood, C.; Davis, A. M. Inequities in family quality of life for african-american families raising children with disabilities. Soc. Work Public Health 2019, 34 (1), 102–112. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D.; Woloski, M.; Feeny, D.; McCusker, P.; Wu, J.; David, M.; Bussel, J.; Lusher, J.; Wakefield, C.; Henriques, S.; et al. Development of disease-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments for children with immune thrombocytopenic purpura and their parents. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2003, 25 (1), 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A., Mas, J. M., Baqués, N., Simón, C., & García-Ventura, S. The spanish family quality of life scales under and over 18 years old: Psychometric properties and families’ perceptions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(21), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Eskow, K.; Pineles, L.; Summers, J. A. Exploring the effect of autism waiver services on family outcomes. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2011, 8 (1), 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J.; Higgins, K.; Pierce, T.; Whitby, P. J. S.; Tandy, R. D. Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: Families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil, 2017, 70, 152–162. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Family demographics, parental stress, and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15 (1), 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T. L.; Carter, E. W. Family Quality of Life and its correlates among parents of children and adults with intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 124 (2), 99–115. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P. S.; Tarraf, W.; Marsack, C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): Evaluation of internal consistency, construct, and criterion validity for socioeconomically disadvantaged families. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38 (1), 46–63. [CrossRef]

- Schertz, M.; Karni-Visel, Y.; Tamir, A.; Genizi, J.; Roth, D. Family Quality of Life among families with a child who has a severe neurodevelopmental disability: impact of family and child socio-demographic factors. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53–54, 95–106. [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Kirby, N.; Shearer, J.; Nettelbeck, T. Family Quality of Life of Australian Families with a Member with an Intellectual/Developmental Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56 (1), 71–86. [CrossRef]

- Kyzar, K. B.; Brady, S. E.; Summers, J. A.; Haines, S. J.; Turnbull, A. P. Services and supports, partnership, and Family Quality of Life: Focus on deaf-blindness. Except. Child. 2016, 83 (1), 77–91. [CrossRef]

- Kyzar, K.; Brady, S.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Family Quality of Life and partnership for families of students with deaf-blindness. Remedial and Special Education. 2018, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. W.; Wegner, J. R.; Turnbull, A. P. Family Quality of Life following early identification of deafness. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41 (2), 194–205. [CrossRef]

- Taub, T.; Werner, S. What support resources contribute to family quality of life among religious and secular jewish families of children with developmental disability? J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41 (4), 348–359. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P. S.; Hobden, K. L.; LeRoy, B. W. Families of children with autism and developmental disabilities: A description of their community interaction. Res. Soc. Science and Disabil. 2011, 6, 49-83. [CrossRef]

- Susanto, T., Rasni, H., & Susumaningrum, L. A. Prevalence of malnutrition and stunting among under-five children: A cross-sectional study family of quality of life in agricultural areas of Indonesia. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2021, 14(2), 147–161. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P. S.; Pociask, F. D.; Dizazzo-Miller, R.; Carrellas, A.; LeRoy, B. W. Concurrent validity of the International Family Quality of Life Survey. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2016, 30 (2), 187–201. [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.; Poppe, L.; Vandevelde, S.; Van Hove, G.; Claes, C. Family Quality of Life in 25 belgian families: quantitative and qualitative exploration of social and professional support domains. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1123–1135. [CrossRef]

- Epley, P. H.; Summers, J. A.; Turnbull, A. P. Family Outcomes of early intervention: families’ perceptions of need, services, and outcomes. J. Early Interv. 2011, 33 (3), 201–219. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Gavidia-Payne, S. The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the Quality of Life in families of young children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34 (2), 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Summers, J. A.; Marquis, J.; Mannan, H.; Turnbull, A. P.; Fleming, K.; Poston, D. J.; Wang, M.; Kupzyk, K. Relationship of perceived adequacy of services, family-professional partnerships, and Family Quality of Life in early childhood service programmes. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2007, 54 (3), 319-338. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Brown, R.; Karrapaya, R. An Initial look at the quality of life of malaysian families that include children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56 (1), 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. R.; Holloway, S. D.; Domínguez-Pareto, I.; Kuppermann, M. Receiving or believing in family Support? Contributors to the life quality of latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58 (4), 333–345. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S. D.; Dominguez-Pareto, I.; Cohen, S. R.; Kuppermann, M. Whose job is it? Everyday routines and quality of life in latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 7 (2), 104–125. [CrossRef]

- McStay, R. L.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Maternal stress and Family Quality of Life in response to raising a child with autism: From preschool to adolescence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35 (11), 3119–3130. [CrossRef]

- Meral, B. F.; Cavkaytar, A.; Turnbull, A. P.; Wang, M. Family Quality of Life of turkish families who have children with intellectual disabilities and autism. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2013, 38 (4), 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S. A.; Fontanella, B. J. B.; de Avó, L. R. S.; Germano, C. M. R.; Melo, D. G. A Qualitative study about quality of life in brazilian families with children who have severe or profound intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32 (2), 413–426. [CrossRef]

- Valverde, B. B. R., & Jurdi, A. P. S. Analysis of the relationship between early intervention and family quality of life. Revista Brasileira de Educacao Especial 2020, 26(2), 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Bello-Escamilla, N.; Rivadeneira, J.; Concha-Toro, M.; Soto-Caro, A.; Diaz-Martinez, X. Family Quality of Life Scale (FQLS): validation and analysis in a chilean population. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16 (4), 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. I.; MacAdam-Crisp, J.; Wang, M.; Iaroci, G. Family Quality of Life when there is a child with a developmental disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2006, 3 (4), 238–245. [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Grau-Sevilla, M.D. Factor structure and internal consistency of a spanish version of the family quality of life (FaQoL). Applied Research in Quality of Life 2017, 13, 385–398. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Grau, P., McWilliam, R. A., Martinez-Rico, G., Morales-Murillo, C. P., García-Grau, P., McWilliam, R. A., ... Morales-Murillo, C. P. Child, Family, and Early Intervention Characteristics Related to Family Quality of Life in Spain. Journal of Early Intervention 2019, 41(1), 44–61. [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P., McWilliam, R. A., Martínez-Rico, G., & Morales-Murillo, C. P. Rasch Analysis of the Families in Early Intervention Quality of Life (FEIQoL) Scale. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2021, 16(1), 383-399. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Giné, C.; Vilaseca, R.; Gràcia, M.; Mora, J.; Orcasitas, J. R.; Simón, C.; Torrecillas, A. M.; Beltran, F. S.; Dalmau, M.; Pro, M. T.; et al. Spanish Family Quality of Life Scales: Under and over 18 Years Old. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 38 (2), 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, T.; Boxum, A. G.; Hamer, E. G.; La Bastide-Van Gemert, S.; Dirks, T.; Reinders-Messelink, H. A.; Maathuis, C. G. B.; Verheijden, J.; Geertzen, J. H. B.; Hadders-Algra, M. LEARN2MOVE 0–2 years, a randomized early intervention trial for infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: Family outcome and infant’s functional outcome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Leadbiter, K.; Aldred, C.; McConachie, H.; Le Couteur, A.; Kapadia, D.; Charman T.; Mcdonald, W.; Salomone, E.; Emsley, R.; Green, J. The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ): An ecologically- valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 1042–1062.

- Lei, X., & Kantor, J. (2020). Social support and family quality of life in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorder: The mediating role of family cohesion and adaptability. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Song, Q., Zhu, L., Chen, D., Xie, J., Hu, S., … Tan, L. Family Management Style Improves Family Quality of Life in Children With Epilepsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 2020, 52(2), 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., · Cinanni, N., Di Cristofaro, N., Lee, N · Dillenburg, R., ·. Adamo, K. B., · T. Mondal, T., · Barrowman, T. . Shanmugam, G,·. Timmons, B. W ·Longmuir, P. W. Parents of Very Young Children with Congenital Heart Defects Report Good Quality of Life for Their Children and Families Regardless of Defect Severity, Pediatric Cardiology 2020, 41, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Neikrug, S.; Roth, D.; Judes, J. Lives of Quality in the face of challenge in Israel. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1176–1184. [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Isaacs, B. Validity of the Family Quality of Life Survey-2006. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 28 (6), 584–588. [CrossRef]

- Tait, K.; Fung, F.; Hu, A.; Sweller, N.; Wang, W. Understanding Hong Kong chinese families’ experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46 (4), 1164–1183. [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Ortigosa, E. M.; Flores-Rojas, K.; Moreno-Quintana, L.; Muñoz-Villanueva, M. C.; Pérez-Navero, J. L.; Gil-Campos, M. Health and socio-educational needs of the families and children with rare metabolic diseases: qualitative study in a tertiary hospital. An. Pediatr. 2019, 90 (1), 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Verger, S., Riquelme, I., Bagur, S., & Paz-Lourido, B. Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Families Participating in Two Different Early Intervention Models in the Same Context: A Mixed Methods Study. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Mannan, H., Poston, D., Turnbull, A. P., & Summers, J. A. Parents’ perceptions of advocacy activities and their impact on family quality of life. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2004, 29(2), 144–155. [CrossRef]

- McStay, R. L.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Stress and Family Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent Gender and the Double ABCX Model. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44 (12), 3101–3118. [CrossRef]

- Mello, C., Rivard, M., Terroux, A., & Mercier, C. Quality of Life in Families of Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. American Journal On Intellectual and Disabilities 2019, 124(6), 535–548. [CrossRef]

- Vanderkerken, L., Heyvaert, M., Onghena, P., & Maes, B. The Relation Between Family Quality of Life and the Family-Centered Approach in Families With Children With an Intellectual Disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2019, 16(4), 296-311. [CrossRef]

- Demchick, B. B.; Ehler, J.; Marramar, S.; Mills, A.; Nuneviller, A. Family quality of life when raising a child with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2019, 12 (2), 182–199. [CrossRef]

- Moyson, T.; Roeyers, H. The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better’. Quality of Life of siblings of children with intellectual disability: The siblings’ perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56 (1), 87–101. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R., Ali, F. M., Finlay, A. Y., & Salek, M. S. Family reported outcomes, an unmet need in the management of a patient’s disease: Appraisal of the literature. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2021, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Giné, C., Mas, J., Balcells-Balcells, A., Baqués, N. & Simón, C. Escala de Calidad de Vida Familiar con hijos/as con hijos menores de 18 años con discapacidad intelectual y/o en el desarrollo, Versión Revisada 2019, CdVF-ER (<18) Madrid: Plena Inclusión. 2019.

- Rodríguez-Cely, D. y Espina-Salazar, A. Epistemologías otras en la investigación en diseño: Transformaciones para el diseño inclusivo. Bitácora Urbano Territorial 2020, 30(II), 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Life as narrative. J. Bruner. In search of pedagogy. The selected works of Jerome Bruner.. Routledge: New York, 2006, Vol. 2, 129–140: . [CrossRef]

- Brown, R., & Schippers, A. The background and development of Quality of Life and Family Quality of Life: applying research, policy, and practice to individual and family living. International Journal of Child Youth & Family Studies 2018, 9(4), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Aldersey, H. M., Francis, G. L., Haines, S. J., & Chiu, C. Y. Family Quality of Life in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2016, 14(1), 78-86. [CrossRef]

- Van Heumen, L., & Schippers, A. Quality of life for young adults with intellectual disability following individualised support: Individual and family responses†. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability , 41(4), 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Correia, R. A., Seabra-Santos, M. J., Campos Pinto, P., & Brown, I. (2017). Giving Voice to Persons With Intellectual Disabilities About Family Quality of Life. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 14(1), 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Jhul, P. Preverbal children as co-researchers: Exploring subjectivity in everyday living, in Theory & Psychology 2018, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Arestedt, L., Benzein, B., Persson, C. & Rämgard, M. A shared respite—The meaning of place for family well-being in families living with chronic illness. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 2016, 11(1), 30308. [CrossRef]

- Noyek, S., Davies, T., Batorowicz, B., Delarosa, E. y Fayed, N. The “Recreated Experiences” Approach: Exploring the Experiences of Persons Previously Excluded in Research, International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2022, 21, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Creighton, G.; Oliffe, J. L.; Ferlatte, O.; Bottorff, J.; Broom, A.,; Jenkins, E.K. Photovoice ethics: Critical reflections from men’s mental health research. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28 (3) 446–455. [CrossRef]

- Egaña, D. y Barría, S. La familia como categoría difusa en la atención primaria del sistema de salud chileno, Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral 2015, 11, 3, 1-15.

| Approach |

Participants |

Number of studies | Authors |

|

Traditional Approach (nF = nP) |

50%-69% mothers | 7 | Rivard et al. [25]; Feng et al. [26]; Huang et al. [27]; Mas et al. [28]; Levinger et al. [29]; Schlebusch et al. [30]; Schlebusch et al. [31]. |

| 70%-89% mothers | 22 | Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir [32]; Córdoba et al [33]; Verdugo et al. [34]; Chiu et al., [35]; Waschl et al. [36]; Escorcia et al. [37]; Giné et al. [38]; Balcells-Balcells et al. [39]; Balcells-Balcells et al. [40]; Bhopti et al. [41]; Chiu et al. [42]; Hoffman et al. [43]; Algood and Davis [44]; Barnard et al. [45]; Balcells-Balcells et al. [46]; Eskow et al. [47]; Hsiao et al. [48]; Hsiao et al. [49]; Boehm y Carter [50]; Samuel et al. [51]; Schertz et al. [52]; Rillotta et al. [53]. | |

| 90%-99% mothers | 12 | Kyzar et al. [54]; Kyzar et al. [55]; Jackson et al. [56]; Taub y Werner [57]; Samuel et al. [58]; Susanto et al. [59]; Samuel et al. [60]; Steel et al. [61]; Epley et al. [62]; Davis y Gavidia Payne [63]; Summers et al. [64]; Clark et al. [65] | |

| Mothers only | 6 | Cohen et al. [66]; Holloway et al. [67]; McStay et al. [68]; Meral et al. [69]; Rodrigues et al. [70]; Valverde y Jurdi [71] | |

| Not specified |

18 | Bello-Escamilla et al. [72]; Brown et al. [22]; Brown et al. [73]; García Grau et al. [74]; García Grau et al. [75]; García Grau et al. [76]; Giné et al. [77]; Hielkema et al. [78]; Leadbitter et al. [79]; Lei et al. [80]; Liu et al. [81]; Lee et al. [82]; Neikrug et al. [83]; Perry e Isaacs [84]; Tait and Husain [85]; Tejada-Ortigosa et al. [86]; Verger et al., [87]; Wang et al. [88]. | |

| New approaches (nF < nP) |

Systemic | 1 | Vanderkerken et al. [24]. |

| Dyads fathers / mothers | 5 | Wang et al., [23]; McStay et al., [89]; Mello et al. [90]; Vanderkerken et al. [91]; Demchick et al. [92] | |

| Siblings | 1 | Moyson et Royers [93]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).