1. Introduction

Global educational institutions have been compelled to implement e-learning on a massive scale due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been a challenge for many students and instructors. However, it has also prompted the development of some novel educational approaches (Zu et al., 2020). Pandemics and natural disasters should be accounted for in companies' and other entities' emergency plans. In such situations, the performance and efficacy of information and communication technology (ICT) systems and OL resources such as massive open online courses and digital books are essential (Dhawan, 2020). Online learning's SWOC (strengths, limitations, opportunities, and challenges) should be assessed, and these factors should be considered when implementing. The advantages include flexibility in locations and times and swift responses.

One must evaluate the tools and educational materials employed to use OL successfully. The institutions must clearly understand how the requirements of students, instructors, and content (LEC) are satisfied. Finding out what students hope to get from their university experience might help educational institutions improve student happiness while boosting their potential for future success (Leo et al., 2021). The education process can be carried out in several ways, such as in a synchronous, asynchronous, mixed, or blended format. Because the contact between instructors in synchronous learning is comparable to that in conventional education and because teachers include gamification in the content of their courses, synchronous learning results in a high degree of learning satisfaction (Tang et al., 2021; Yamagata-Lynch, 2014).

Ensuring every student receives access to the appropriate tools and materials is one of the most challenging issues with OL (Elberkawi et al., 2021). Students have, on occasion, been forced to either share electronic equipment with members of their families or rely on public Wi-Fi networks (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023). It has produced equality difficulties since children from families with poorer incomes may have less access to technology due to this. Another problem with OL is offering learners the necessary amount of social engagement. Students can learn from one another and cultivate relationships with their classmates in a conventional classroom setting. It will not be simple to recreate it online. However, specific technologies like online discussion boards and forums could make it easier. Despite the difficulties, OL has resulted in a few positive outcomes. Students, for instance, can learn at their own pace and access material from anywhere in the world. It can be of significant use to students with hectic schedules or who live in rural areas. OL is a beautiful tool that may assist kids in their learning and development. Despite this, it is necessary to find solutions to the problems presented by OL to ensure that every student has a satisfying educational experience (Abdullah & Kauser, 2023; Slack & Priestley, 2023).

The landscape of education is shifting to accommodate newly developed technology. Zoom, Google Meet, and Microsoft Teams were the most popular web platforms for OL and instruction. There are a multitude of additional platforms available as well. As a result of computer technology advancements, students can now engage in educational activities anywhere globally, just as they would in a traditional classroom setting (Ben-Jacob & Glazerman, 2021; Khuluqo et al., 2021). The adoption of OL is directly proportional to the degree to which students are pleased with the content and format of their courses (Azizan et al., 2022).

Students' preparation level for OL is directly proportional to the kind of schools they attend and the time they spend online. Most students were aware that they might not achieve their educational objectives. On the other hand, students with moderate to high academic performance had a more positive outlook on OL's influence on their intellectual development (Xhelili et al., 2021; Yu, 2021). From a medical standpoint, OL is ineffective because students require face-to-face time with patients to learn (Murphy, 2020). The educational institution can increase learning effectiveness and satisfaction by better understanding the demands of the students (Li & Asante, 2021). The student's health problems may worsen due to anxiety and tension, affecting their academic performance and ability to study online (Zapata-Cuervo et al., 2021). Students' psychological impressions of OL were affected by various characteristics, including motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety.

The abrupt switchover to online education during the pandemic may have impacted students' lecture attendance. Similarly, all classroom-based activities have been shifted to online ones, making curriculum reform the primary responsibility of teachers. Teachers report that children are less engaged than they would be with direct teaching. In a synchronous classroom, teachers can better motivate their students (Walker & Koralesky, 2021). Due to differences in learning styles, OL might be challenging for learners. An effective learning environment necessitates using both synchronous and asynchronous learning strategies. Their parents' involvement influences students' attitudes and actions toward learning in OL. Students are open to using this OL if it has a straightforward interface (Mo et al., 2021).

Because students will encounter many technical challenges throughout their education, educational institutions are responsible for providing them with training and digital support whenever required. In addition, not every student is at ease with acquiring knowledge online. It is possible that the setting they have will determine the level of comfort they have. For instance, they could not locate a peaceful location, which resulted in disruptions throughout their scheduled class time. As a result, educational institutions ought to ensure that all students have access to the relevant materials and classes (Bhowmik & Bhattacharya, 2021). Another obstacle is getting permission to use the camera during class time. Many students experience discomfort due to social difficulties, such as the environment not reflecting their culture (Barzani & Jamil, 2021).

It is conceivable that OL remained employed even after the COVID-19 pandemic slowed down. However, for OL to be successful, it is essential to consider the factors. It includes the quality of the e-learning platform, quality of the content, support of teachers and staff, accessibility, and engagement of students (Bilal et al., 2022). A critical behavioral strategy that might maximize the relationship between motivation and task performance is self-assessment practice (Mendoza et al., 2023). According to Tran and Nguyen (Tran & Nguyen, 2022), three variables contribute to an improvement in a student's overall level of happiness with their OL: the efficiency of the course, the provision of knowledge and skills, and an impression of participation.

This study, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on gender equality (SDG 5) and quality education (SDG 4), aims to assess the satisfaction levels of male and female students from different colleges with Online Learning (OL) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The survey, disseminated by the Secretariat of the E-learning Officials Committee at Arab Gulf Cooperation Universities, reached a diverse group of students during the pandemic. This period saw a significant shift in educational delivery methods, including synchronous online learning (SOL), asynchronous online learning (AOL), and blended online learning (BOL), which is a mix of SOL and AOL. While many studies have explored students' overall satisfaction with online education, our study uniquely focuses on the satisfaction levels of Arab male and female students, intending to identify and address gender-specific differences in OL. The outcomes of this study aim to enhance the OL experience for all students, thereby contributing to the global pursuit of inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting gender equality. The research questions (RQs) guiding this study are as follows:

RQ1: Do the students improve any skills during the OL?

RQ2: How do factors like satisfaction, interaction, challenges, teaching style, and health issues affect the perception of OL with male and female students?

This research aims to explore the experience of college students in online learning, particularly focusing on gender differences. The study is conducted in the context of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations and investigates aspects such as satisfaction with online learning, course content delivery, interaction with instructors, behavioral changes, and challenges faced during OL. The key objective is to understand how these factors differ between male and female students and their overall impact on the online learning experience.

The rest of the article operates in the following order: Section two explains the materials and methods. Section three displays the results, followed by the discussion in Section four. And finally, the conclusions are given in Section five.

2. Materials and Methods

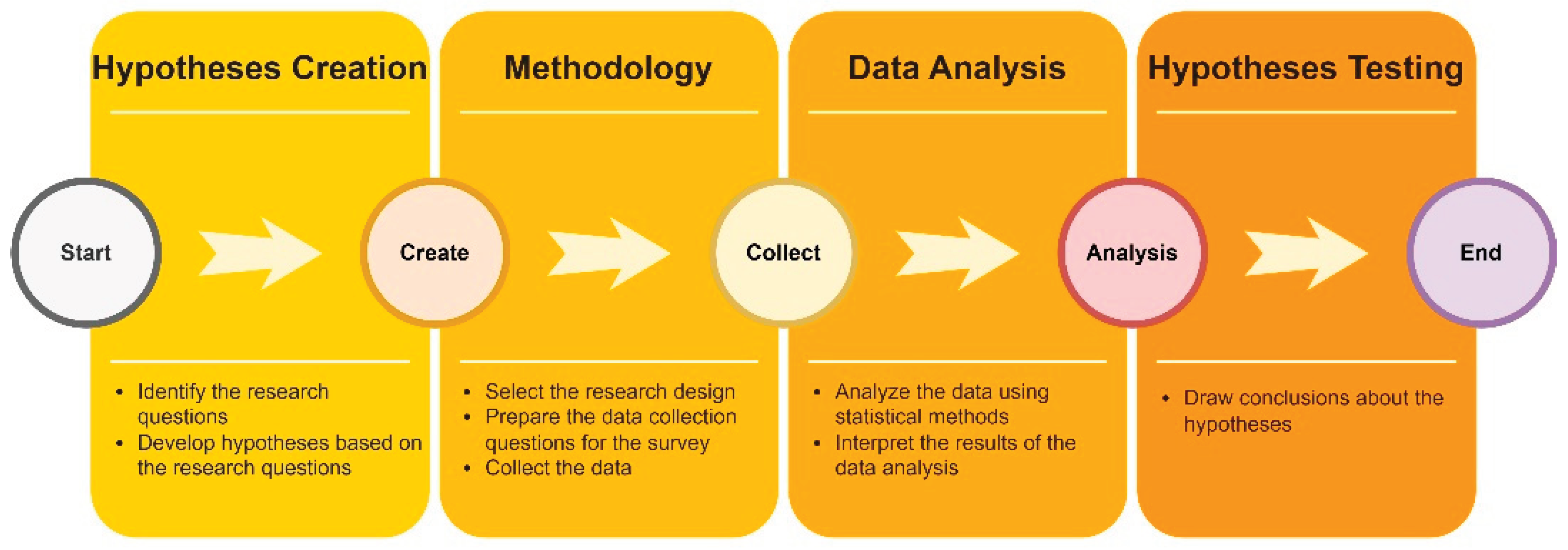

Figure 1 presents a visual representation of the study's methodology. The stages include the creation of hypotheses, research design, choice of data collection method, data collection, analysis, and hypotheses evaluation.

2.1. Hypothesis design

During the process of constructing the conceptual framework for our study, we generated hypotheses based on the research questions, which are listed below.

H1: There is no significant association between gender and OL methods (synchronous, asynchronous, and blended).

H2: There is no significant association between gender and computer experience (beginner, intermediate, and expert).

H3: No significant association exists between the OL experience for male and female students before the pandemic.

H4: There is no significant difference between the male and female students' satisfaction levels concerning OL.

H5: There is no significant difference between the male and female students' levels of interaction during the OL.

H6: No significant difference exists between male and female students' behavioral changes or health issues during OL.

H7: There is no significant difference between the male and female students' levels of OL challenges during learning.

H8: There is no significant difference between the male and female students' levels of teaching style perception during the OL (including the content quality).

The online questionnaire poll is sent to higher educational institutions and schools in all GCC countries by the Secretariat of the E-learning Directors Committee at the Universities and Higher Education Institutions of GCC. The questionnaire has multiple-choice and Likert scale questions. The data was gathered between June and December 2021 through Google surveys, and the responses to questionnaires were submitted by students attending various educational institutions located among the GCC's six member states. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Kingdom of Bahrain, Kuwait, the Sultanate of Oman, and Qatar are these countries. The questionnaire covered five topics: interaction, satisfaction, teaching style, challenges, and health problems. The range of responses for each Likert scale question is from one to five (from strongly disagreeing to strongly agreeing).

The research is being done with a quantitative approach as its technique. To accomplish this goal, it will first compile the quantitative information the students provided and then analyze the hypotheses statistically. The sampling method used for this research was known as convenience sampling (Etikan et al., 2016). There are numerous benefits associated with convenient sampling. First, it is a relatively simple and economical sampling method. Second, it can rapidly collect information from many participants. Thirdly, it can collect data from a particular population, such as college students in GCC nations.

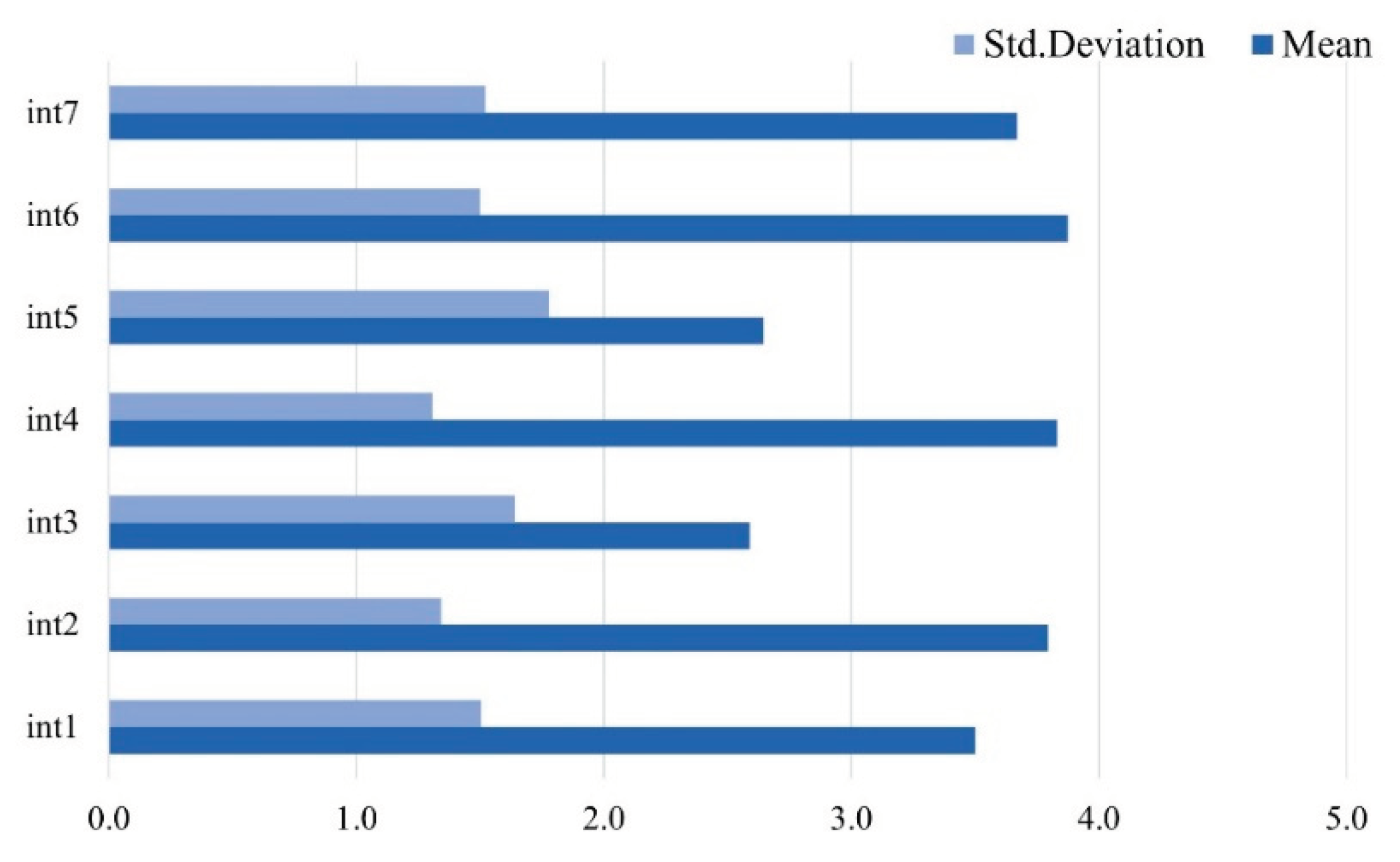

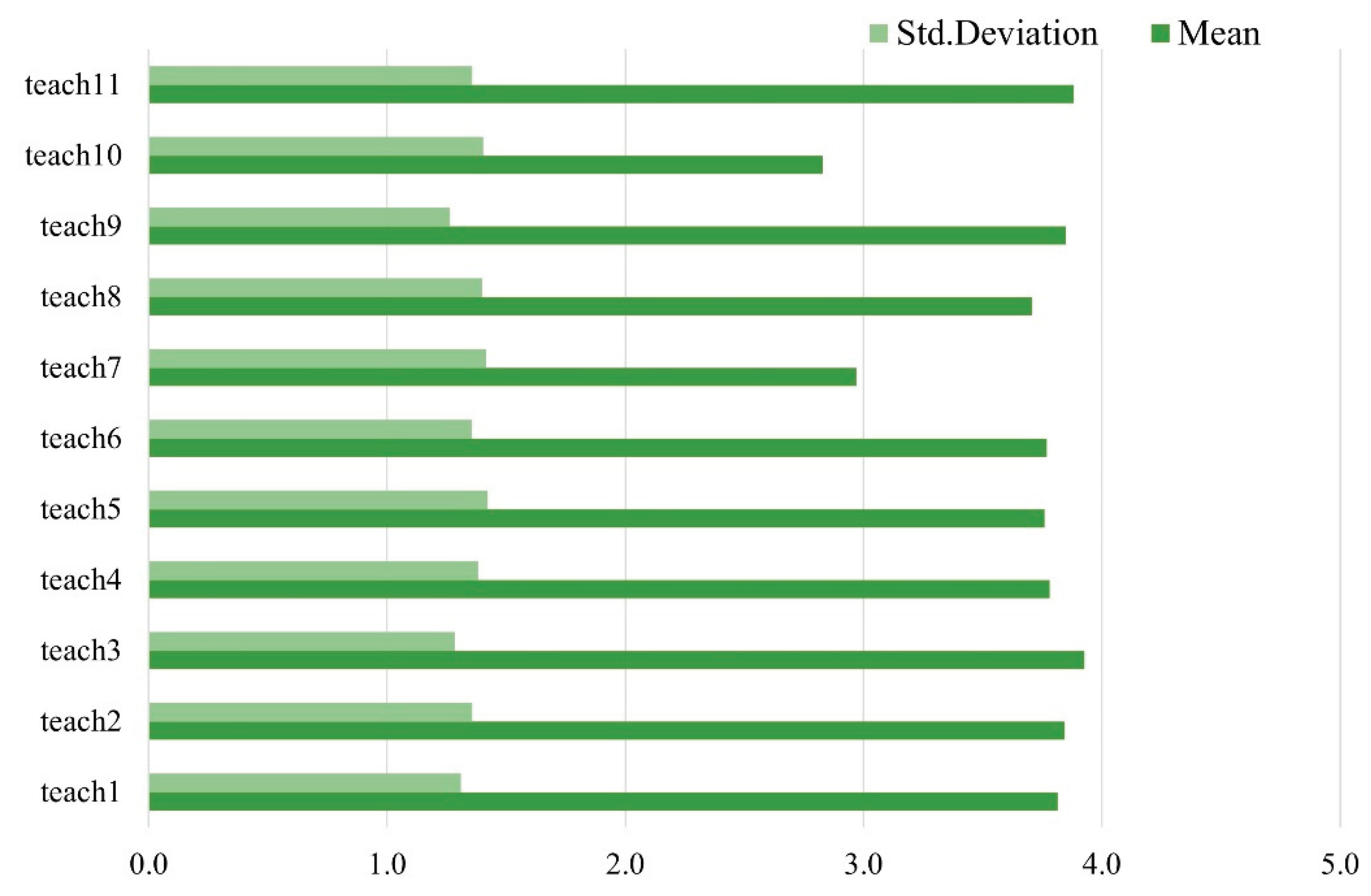

The data was examined using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29 (IBM Corp, 2022). Table A1 (Appendix A) illustrates the mean value and the standard deviation (std deviation) for each construct. The interaction construct has seven items, which deal with the communication between peer students, teachers, parents, and institutions (as shown in

Figure 2). Almost all students are satisfied with interacting with their teachers or institutions during their OL.

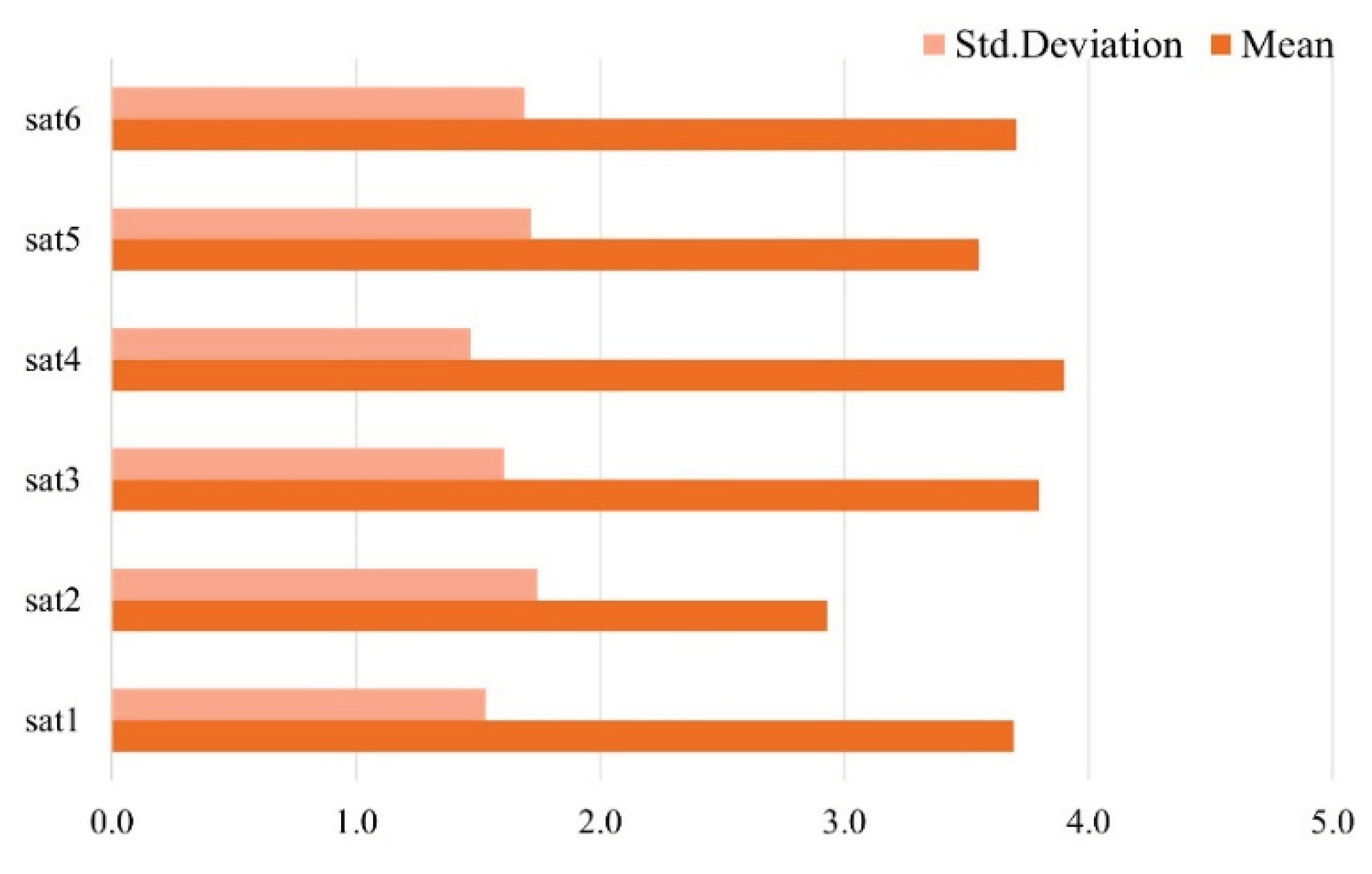

The satisfaction construct contains six items, as described in

Figure 3. The students are delighted with the OL method preferred by their institution. Even the students prefer to use OL in their future curriculum if provided.

Each student has different challenges on OL during the COVID-19 pandemic. It includes their concentration, isolation, workloads, and much more, as in

Figure 4. The students mentioned that they were not disturbed during class hours by other students in OL (cha6). Most of the queries have responses marked as neutral to agree.

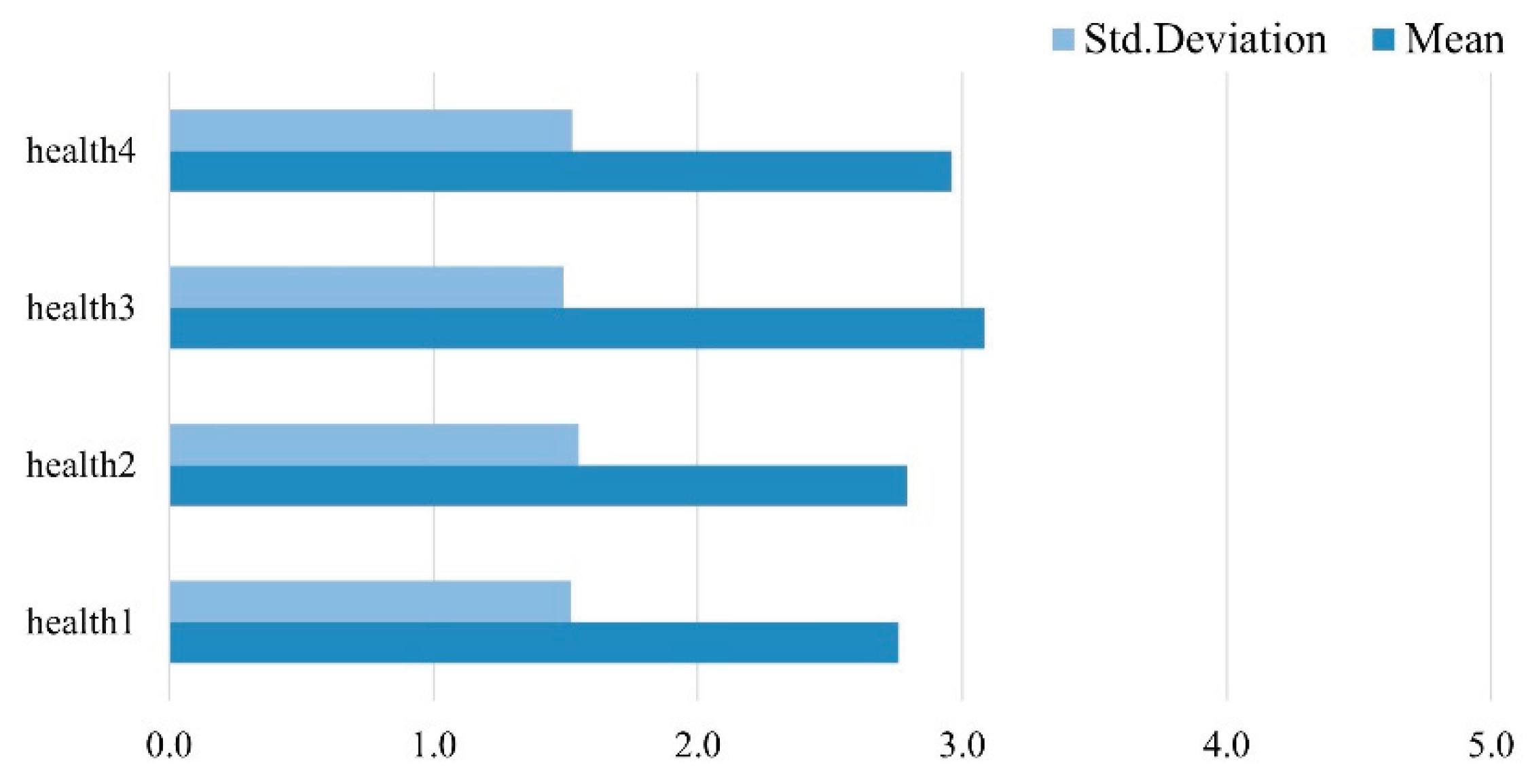

The numbers in

Figure 5 show that many students are having health problems. Anxiety or stress is the most common health problem, followed by less physical exercise and frequent health problems like headaches, blurred vision, and back pain. Some students also said they felt shy or worried when taking online classes with a camera.

Lessons offered during online education may change from one instructor to the next and from topic to topic. Almost all students liked the content style their teachers or professors delivered, as shown in

Figure 6.

Other than the constructs, specific demographic and categorical responses were also collected from the students. It includes gender, grade, country, computer literacy, OL method employed during learning, information about the e-library provided during OL, and OL experience before the pandemic.

3.1. Hypothesis evaluation

We conducted an ordinal regression analysis for questions based on the Likert scale. The dependent variable is an ordinal or Likert scale score, while the independent variable is categorical (Liu, 2009; Spais & Vasileiou, 2006). Cronbach's alpha measures construct internal consistency. The closest alpha value to 1 is more reliable. Reliability is satisfactory if the value is above 0.7 (George & Mallery, 2019).

Table 1 shows that all survey constructs are reliable.

4. Results

Responses from 8,895 students were gathered from various GCC countries. Over half (4803) of the students who responded were female (54%), whereas 46% were male. No responses were received from college students in Qatar, while 64.2% were from Saudi Arabia, 29.7% were from Kuwait, 6% were from Bahrain, and 0.1% were each from Oman and UAE, respectively. The complete data analysis based on gender is described in

Table 2. Most females (49.65%) and males (43.61%) fall into the "Undergraduate" category. 94.05% of responses are from public or government institutions, while 5.95% are from private institutions. Of females, 36.23% had no prior OL experience before the pandemic, while 17.76% had previous exposure. On the other hand, the percentages for males were 31.48% and 14.53%, respectively. E-library usage is relatively high, with 25.72% of females and 24.96% of males using e-libraries regularly. Additionally, 17.27% of females and 13.15% of males utilize e-libraries occasionally. Of the total responses, students with SOL learning were 65.93%, 26.15% with BOL, and 7.92% with AOL.

4.1. Hypotheses Analysis

The chi-square test represents a non-parametric test that ignores any assumptions about how the data should be distributed. It is possible to determine whether or not two category variables are connected by employing the chi-square test of independence (Janes, 2001). The null hypothesis states that the two variables have no significant relationship. We can conclude to accept the null hypothesis if the p-value is higher than 0.05; else, reject it.

The chi-square test analysis is represented in

Table 3. The gender variable with the categories OL methods (H1 hypothesis) and computer experience (H2) shows a p-value below 0.05; hence, we reject the null hypothesis. Thus, it offers a significant association between these variables and male and female students. However, OL experience before the pandemic has no relationship with the gender variable (H3), as the p-value is higher than 0.05; hence, we accept the null hypothesis.

An ordinal regression analysis was carried out to verify the construct hypotheses, and the findings are presented in

Table 4. The gender variable is considered in the study of the model. There is a null hypothesis in the information about fitting the model. This hypothesis states that there is no significant difference when comparing the initial model (which did not include any independent variables) to the final model (which did have an independent variable). We accept the null hypothesis when the p-value>0.05 (significant value). It is recommended that the null hypothesis in the model fitness table should be rejected so that the model can be correctly used for analysis.

We analyze the parameter estimate table to find the relationship between the outcomes. It is an essential interpretation of the hypothesis analysis.

Table 5 represents the analysis of ordinal regression with the constructs. The male parameter is considered a reference parameter and is valued as zero. When the estimated value is negative, there is less acceptance level than the reference parameter. The null hypothesis states no significant difference in location parameters (gender) towards the response parameters (constructs). It is accepted when the p-value (significant value) exceeds 0.05. From

Table 5, we conclude that all hypotheses are rejected, as the p-value is less than 0.05.

5. Discussion

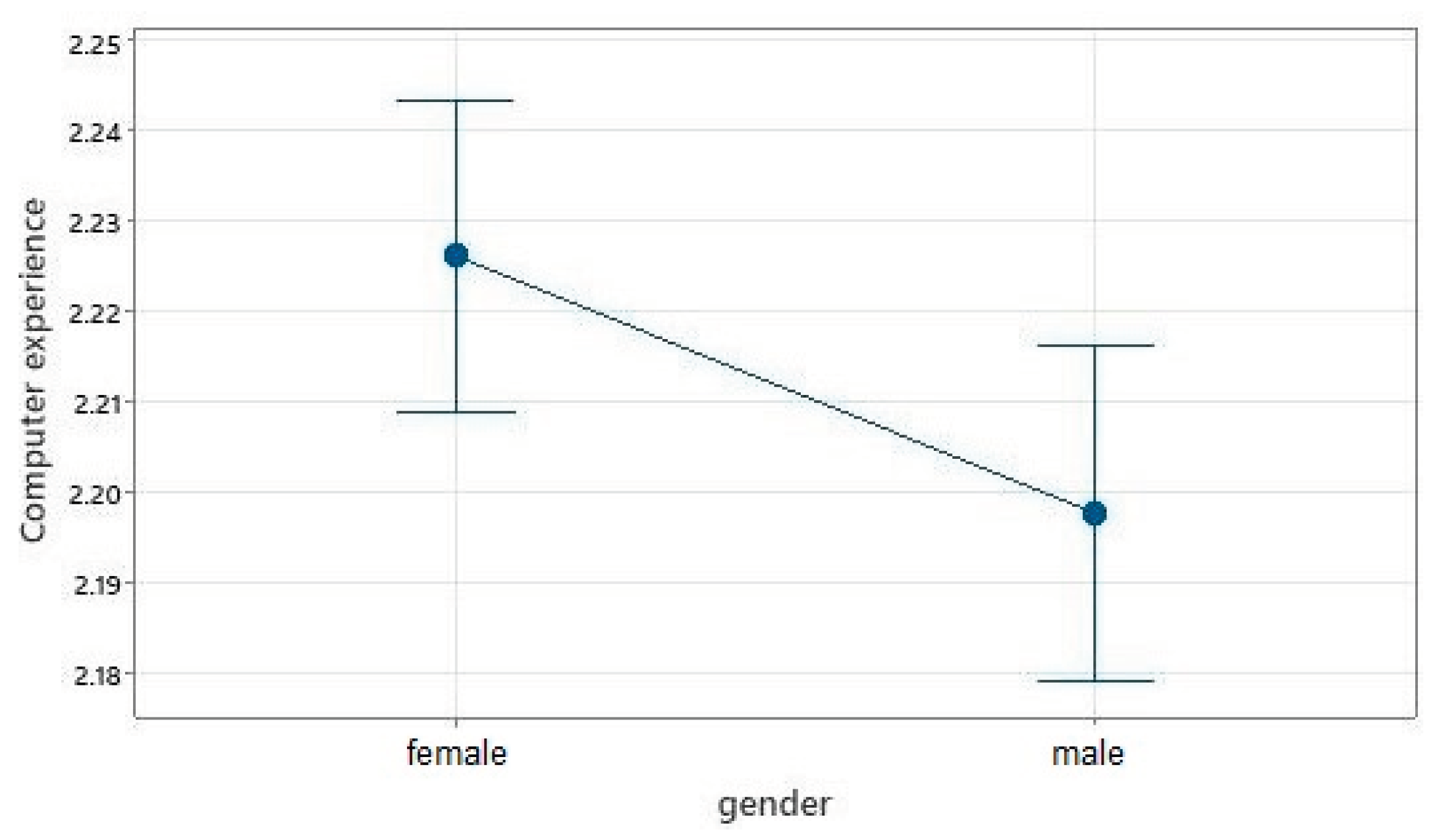

The study focused on different aspects of OL from the male and female students, who are graduates and undergraduates from GCC nations. A total of 8,895 responses were collected through an online survey, which the Secretariat of the E-learning Officials Committee at Arab Gulf Co-operation Universities distributed. Around 46% were male students, and the remaining 54% were female. The gender variable has a significant relationship with the OL methods like SOL, AOL, and BOL with the p-value <0.05 (H1 rejected). Also, the computer experience with gender has a p-value<0.05 (H2 rejected).

Figure 7 shows that males have an average computer experience of 2.197. In contrast, females have an average computer experience of 2.226. According to this, females, on average, have slightly more experience working with computers than males. However, the proximity of the confidence intervals indicates that any variation in mean computer experience is likely to be minimal. There is no association between gender and OL experience before the pandemic (p-value>0.05, H3 accepted). The hypothesis decision is concluded in

Table 6.

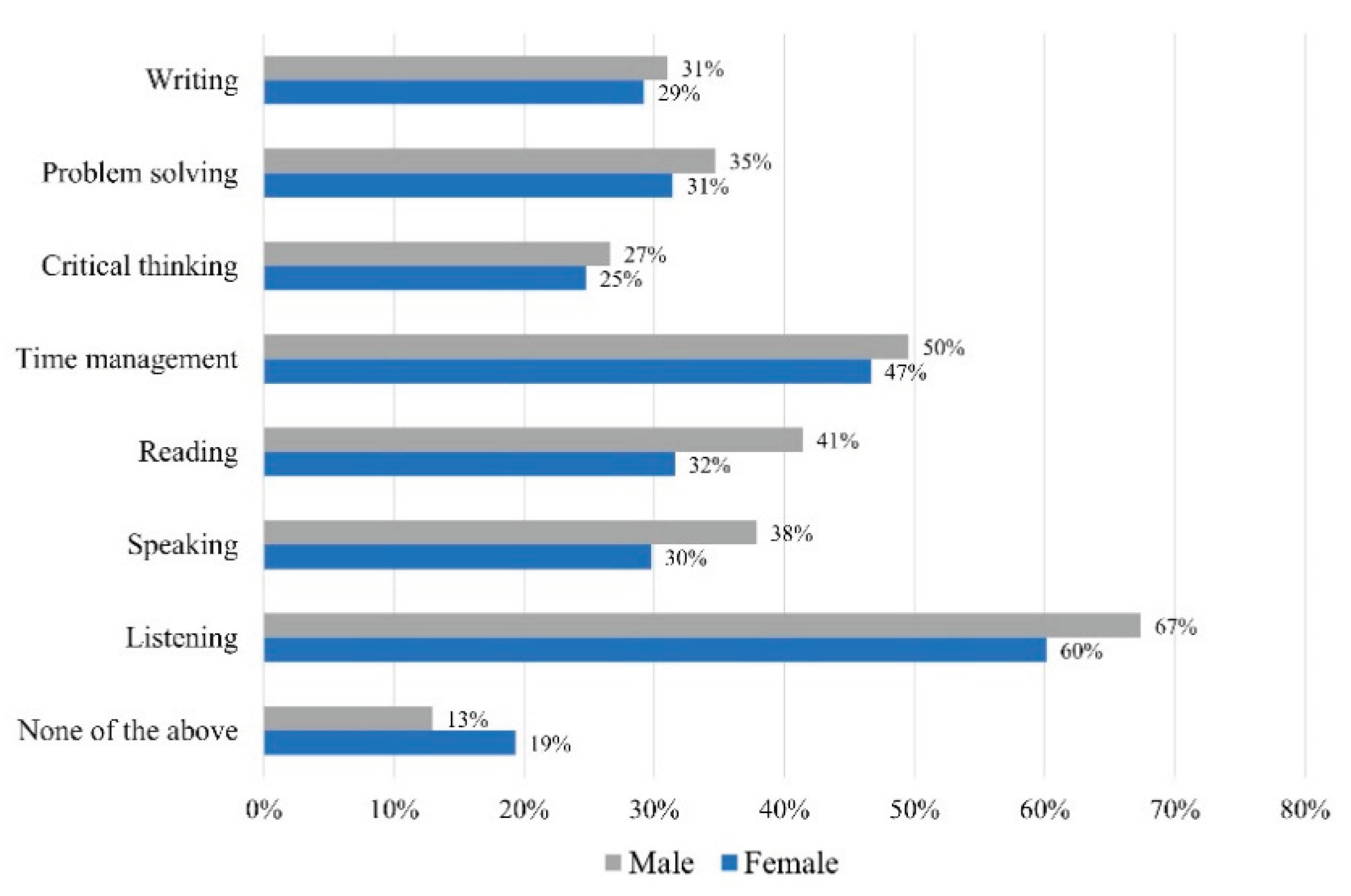

The students thought that they had improved a variety of skills throughout the OL, including their listening ability, reading, speaking, and writing abilities, as well as many other skills, as shown in

Figure 8. Around 60% of female and 67% of male students showed increased listening skills, followed by time management (50% and 47% for male and female students, respectively). On the other hand, 19% of female and 13% of male students responded that they never felt any changes.

The importance of the institutional support given to the students and instructors during the OL cannot be overstated. Students' mental states should be considered during OL, and teachers are responsible for motivating students to overcome these challenges (Bolatov et al., 2021). Student satisfaction is the most crucial indicator of a successful educational experience, whether in a traditional classroom or virtually (Li & Asante, 2021). The instructor can create the course content better if the factors affecting learning efficacy are identified (Kauffman, 2015). Studies have shown that students' satisfaction with OL is influenced by various factors, including their learning style, prior experience with OL, and the level of support they receive from the instructor and the institution (Ho et al., 2021; Kim & Kim, 2021; Muthuprasad et al., 2021). Students who are satisfied with OL tend to be more engaged and successful in their studies. Interaction between teachers and students during OL is essential for a successful learning experience.

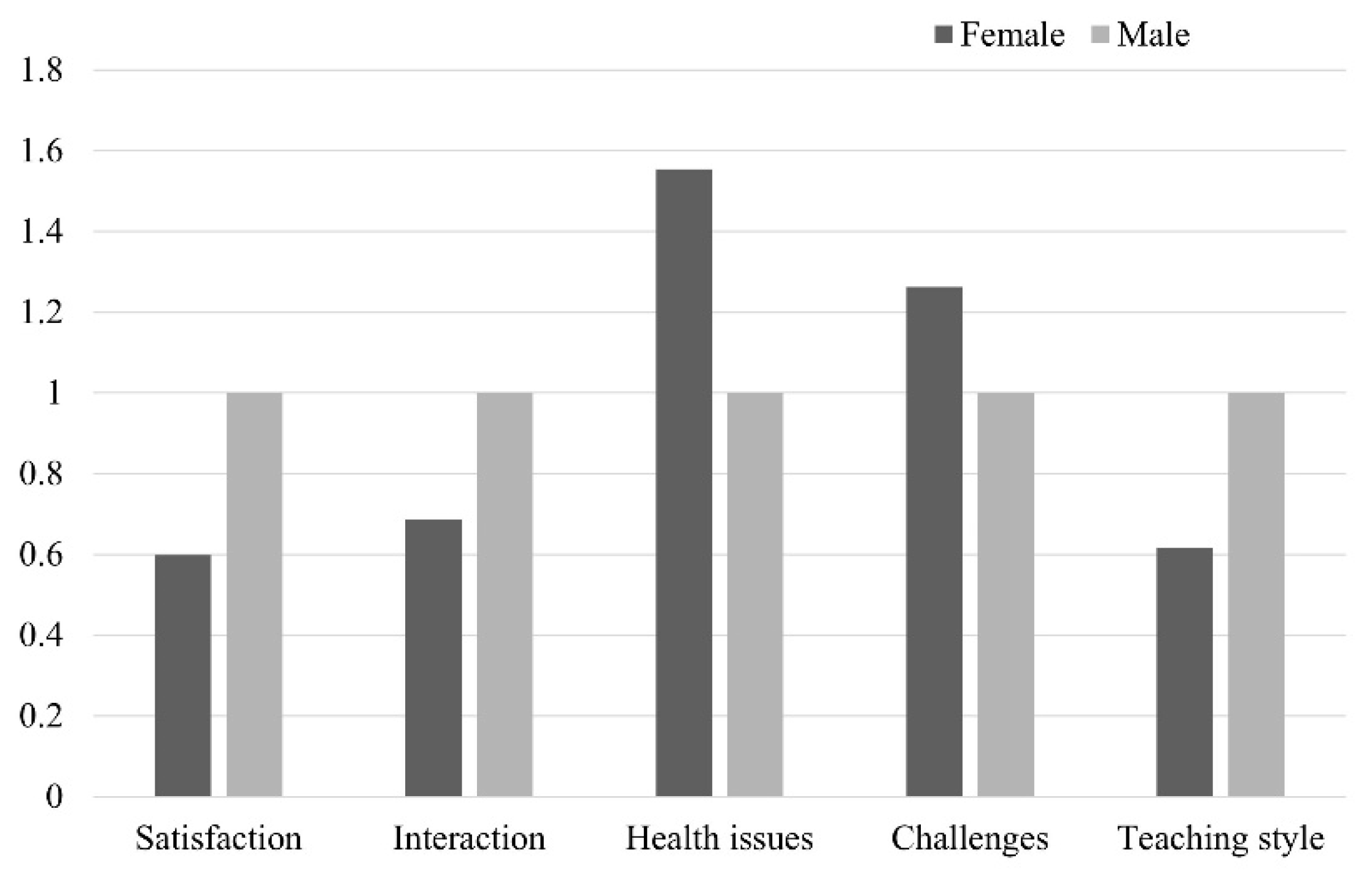

The ordinal regression for the constructs showed that all factors, such as interaction, satisfaction, challenges, health, and teaching style, significantly differed between the male and female students' acceptance levels. The p-value is less than 0.05 for all the constructs; hence, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H8 are rejected. The estimated value can be observed from the parameter estimate in

Table 5. The exponential of this value shows how the acceptance level of female and male students differs, as depicted in

Figure 9. The reference variable is male students; hence, the value is 1. Female students are less satisfied than male students by 0.599 times. Also, female students' interaction and teaching style acceptance are 0.687 and 0. 617 times less than male students, respectively. During the OL, female students encountered more problems than male students regarding health and challenges, with 1.554 times and 1.262 times, respectively. It can be due to cultural expectations, home environments, and health-related factors.

5.1. Limitation and Future Work

This study has a limitation that can be attributed to the fact that the sample of students had very few or no replies from Oman, the UAE, and Qatar. In the subsequent study, there needs to be a greater inclusion of samples to ensure a broader representation. In addition, the following phase includes the possibility of researching the various learning styles of the students, which can then be applied to the process of individualizing the educational experience for each student. Teachers can better meet their student's needs and learning styles by considering these factors as they develop lesson plans and course content. This method creates a more stimulating and productive classroom setting, improving students' knowledge and retention.

6. Conclusions

This study examines college students' OL experiences, concentrating on gender differences. 8,895 GCC nation students were surveyed statistically. Based on the data, we can infer that male students are more satisfied than female students. Most students felt that technical connection issues, heavy workload, lack of concentration, isolation, and difficulty adapting to OL were some of their main challenges during their learning. The differential experiences between female and male students regarding health and challenges during the OL can be influenced by various factors, including sociocultural norms and health-related factors. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach, including providing comprehensive healthcare services and a supportive environment to create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment for all students.

While OL is anticipated to continue in the next generation of education, gender-specific factors must be considered to ensure equal access, accommodate diverse learning preferences, and encourage a gender-inclusive and bias-free learning environment. By resolving these factors, OL can contribute to a more equitable and effective learning environment for students, regardless of gender.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) under project number CORONA PROP 105 / PN2019TM15.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Committee from the Office of the Vice Dean for Academic Affairs, Research and Graduate Studies, College of Engineering and Petroleum of Kuwait University (protocol code 24/2/533).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kuwait University (KU) and KFAS for their continuous support in completing this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The constructs with mean and std deviation for each item.

Table A1.

The constructs with mean and std deviation for each item.

| Construct |

Question |

Mean |

Std Deviation |

| Interaction |

int1: During class time, I engage with other students. |

3.502 |

1.503 |

| int2: During OL, I frequently communicate with my instructors. |

3.794 |

1.342 |

| int3: Outside of scheduled class times, there is no way to communicate with the instructors. |

2.587 |

1.639 |

| int4: The teacher interacts well with students. |

3.832 |

1.307 |

| int5: There is insufficient parent-teacher communication. |

2.645 |

1.778 |

| int6: My parents at home support me in my academic endeavors. |

3.874 |

1.499 |

| int7: My institution offers me the assistance I need for OL. |

3.671 |

1.521 |

| Satisfaction |

sat1: I am pleased that my teacher cannot see me when I am learning. |

3.695 |

1.533 |

| sat2: I miss having other students around when I'm learning. |

2.930 |

1.744 |

| sat3: I am pleased with the OL format. |

3.797 |

1.609 |

| sat4: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the OL platform's existing functions satisfied my learning demands. |

3.901 |

1.469 |

| sat5: Online education is more appealing than traditional classroom education. |

3.551 |

1.716 |

| sat6: If OL becomes an elective in the future curriculum, I will continue to use it. |

3.704 |

1.691 |

| OL challenges |

cha1: I lose connection during live broadcasts, impairing my understanding. |

2.982 |

1.673 |

| cha2: I am occasionally unable to locate a quiet space at home. Consequently, I am unable to concentrate. |

2.521 |

1.805 |

| cha3: I always have difficulty concentrating on the computer. |

2.664 |

1.823 |

| cha4: As a student, I felt more alone. |

2.754 |

1.860 |

| cha5: Excessive workload and assignments in contrast to classroom instruction. |

2.899 |

1.841 |

| cha6: I am annoyed by other students during online lecture hours. |

1.909 |

1.671 |

| cha7: I can inquire about questions to talk about various topics. |

3.853 |

1.383 |

| cha8: I can attain my desired Score through online learning. |

3.794 |

1.474 |

| cha9: OL is more difficult to adapt than face-to-face learning. |

2.570 |

1.830 |

| Health issues |

health1: My anxiousness or stress amount has risen. |

2.759 |

1.520 |

| health2: I am less active than I used to be. |

2.792 |

1.550 |

| health3: I frequently experience health issues such as migraines, blurred vision, and spinal discomfort. |

3.084 |

1.490 |

| health4: I experience shyness or anxiety when joining classes online with a camera present. |

2.959 |

1.525 |

| Teaching style |

teach1: The course's instructional method aided my comprehension of the concept. |

3.815 |

1.309 |

| teach2: I loved the course's instructional style |

3.843 |

1.358 |

| teach3: The method of instruction was adaptable and straightforward. |

3.926 |

1.284 |

| teach4: The instructional method assisted in my educational advancement. |

3.782 |

1.382 |

| teach5: The instructional method inspired me to study more. |

3.759 |

1.423 |

| teach6: The teaching approach was in line with my expectations. |

3.770 |

1.357 |

| teach7: The instruction lacked sufficient opportunities for discussion. |

2.969 |

1.414 |

| teach8: The method of instruction increased my desire to study the topic. |

3.708 |

1.399 |

| teach9: The instructor's instructional strategy facilitated my achievement of course objectives. |

3.849 |

1.264 |

| teach10: The activities and examples did not adequately convey the course's educational content. |

2.828 |

1.404 |

| teach11: Overall, the teaching style was outstanding. |

3.882 |

1.358 |

References

- Abdullah, F., & Kauser, S. (2023, 2023/06/01). Students' perspective on online learning during pandemic in higher education. Quality & quantity, 57(3), 2493-2505. [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2023). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 863-875. [CrossRef]

- Azizan, S., Lee, A., Crosling, G., Atherton, G., Arulanandam, B., Lee, C., & Rahim, R. A. (2022). Online Learning and COVID-19 in Higher Education: The Value of IT Models in Assessing Students' Satisfaction. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 17(3), 245-278. [CrossRef]

- Barzani, S. H. H., & Jamil, R. J. (2021). Students' Perceptions towards Online Education during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jacob, M. G., & Glazerman, A. H. (2021). Technology and Education: A Merger with the Past, Present, and Future. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9(4), 39-42. [CrossRef]

- In The Online Journal of Distance Education and e-Learning, 9; //tojdel.net/journals/tojdel/articles/v09i01/v09i01-08: (1). https; Bhowmik, S., & Bhattacharya, D. (2021). Factors Influencing Online Learning in Higher Education in the Emergency Shifts of Covid 19. The Online Journal of Distance Education and e-Learning, 9(1). https://tojdel.net/journals/tojdel/articles/v09i01/v09i01-08.pdf.

- Bilal, Hysa, E., Akbar, A., Yasmin, F., Rahman, A. U., & Li, S. (2022). Virtual Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Review and Future Research Agenda. Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 15, 1353-1368. [CrossRef]

- Bolatov, A. K., Seisembekov, T. Z., Askarova, A. Z., Baikanova, R. K., Smailova, D. S., & Fabbro, E. (2021). Online-learning due to COVID-19 improved mental health among medical students. Medical science educator, 31(1), 183-192. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Elberkawi, E. K., Maatuk, A. M., Elharish, S. F., & Eltajoury, W. M. (2021). Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Issues and Challenges. 2021 IEEE 1st International Maghreb Meeting of the Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering MI-STA, 902-907. [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American journal of theoretical and applied statistics, 5(1), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 26 step by step: A simple guide and reference. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Ho, I. M. K., Cheong, K. Y., & Weldon, A. (2021). Predicting student satisfaction of emergency remote learning in higher education during COVID-19 using machine learning techniques. PLoS One, 16(4), e0249423. [CrossRef]

- In IBM Corp; IBM Corp In IBM SPSS statistics for windows: (2022). Armonk, NY; IBM Corp. (2022). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp In IBM SPSS statistics for windows, Version 29.0.

- Janes, J. (2001). Categorical relationships: chi-square. Library Hi Tech, 19(3), 296-298. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, H. (2015). A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research in Learning Technology, 23. [CrossRef]

- Khuluqo, I. E., Ghani, A. R. A., & Fatayan, A. (2021). Postgraduate Students' Perspective on Supporting" Learning from Home" to Solve the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(2), 615-623. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Kim, D.-J. (2021). Structural Relationship of Key Factors for Student Satisfaction and Achievement in Asynchronous Online Learning. Sustainability, 13(12), 6734. [CrossRef]

- Leo, S., Alsharari, N. M., Abbas, J., & Alshurideh, M. T. (2021). From Offline to Online Learning: A Qualitative Study of Challenges and Opportunities as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UAE Higher Education Context. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Business Intelligence, 334, 203. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Asante, I. K. (2021). International Students Expectations from Online Education in Chinese Universities: Student-Centered Approach. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. (2009). Ordinal regression analysis: Fitting the proportional odds model using Stata, SAS and SPSS. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 8(2), 30. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, N. B., Yan, Z., & King, R. B. (2023, 2023/02/01/). Supporting students' intrinsic motivation for online learning tasks: The effect of need-supportive task instructions on motivation, self-assessment, and task performance. Computers & Education, 193, 104663. [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.-Y., Hsieh, T.-H., Lin, C.-L., Jin, Y. Q., & Su, Y.-S. (2021). Exploring the Critical Factors, the Online Learning Continuance Usage during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 13(10), 5471. [CrossRef]

- In Medical school assessment during COVID-19: Shelf exams go remote; //www: Retrieved 28 September 2021 from https; Murphy, B. (2020). Medical school assessment during COVID-19: Shelf exams go remote. Retrieved 28 September 2021 from https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/medical-school-assessment-during-covid-19-shelf-exams-go.

- Muthuprasad, T., Aiswarya, S., Aditya, K. S., & Jha, G. K. (2021, 2021/01/01/). Students' perception and preference for online education in India during COVID -19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100101. [CrossRef]

- Slack, H. R., & Priestley, M. (2023). Online learning and assessment during the Covid-19 pandemic: exploring the impact on undergraduate student well-being. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(3), 333-349. [CrossRef]

- Spais, G. S., & Vasileiou, K. Z. (2006). An ordinal regression analysis for the explanation of consumer overall satisfaction in the food-marketing context: The managerial implications to consumer strategy management at a store level. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 14(1), 51-73. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. M., Chen, P. C., Law, K. M., Wu, C. H., Lau, Y.-y., Guan, J., He, D., & Ho, G. T. (2021). Comparative analysis of Student's live online learning readiness during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the higher education sector. Computers & Education, 168, 104211. [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q. H., & Nguyen, T. M. (2022). Determinants in Student Satisfaction with Online Learning: A Survey Study of Second-Year Students at Private Universities in HCMC. International Journal of TESOL & Education, 2(1), 63-80. [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A., & Koralesky, K. E. (2021). Student and instructor perceptions of engagement after the rapid online transition of teaching due to COVID-19. Natural Sciences Education, 50(1). [CrossRef]

- Xhelili, P., Ibrahimi, E., Rruci, E., & Sheme, K. (2021). Adaptation and perception of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic by Albanian university students. International Journal on Studies in Education, 3(2), 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2014). Blending online asynchronous and synchronous learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 189-212. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. (2021). The effects of gender, educational level, and personality on online learning outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Cuervo, N., Montes-Guerra, M. I., Shin, H. H., Jeong, M., & Cho, M.-H. (2021). Students' Psychological Perceptions Toward Online Learning Engagement and Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Students in Three Different Countries. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zu, Z. Y., Jiang, M. D., Xu, P. P., Chen, W., Ni, Q. Q., Lu, G. M., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a perspective from China. Radiology, 296(2), E15-E25. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).