1. Introduction

Although strokes have been documented since about three millennia, they remain today one of the major public issues [

1] as they are the second leading cause of death, the first cause of adult acquired disability and the second most frequent cause of dementia worldwide. Moreover, the lifetime risk of stroke from the age of 25 years onward is almost 25% among both genders [

2]. Based on World Stroke Organization -Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022, in 2019 101 million people worldwide were living with stroke, a figure that had almost doubled over the last 30 years and 12.2 million new strokes were diagnosed per year globally [

1,

3,

4]. In Europe, the prevalence of stroke was 9.5 million people in 2017 and the same year, almost 1.12 million were newly diagnosed with stroke whereas half million deaths were attributed to a stroke [

5].

Due to improvements in awareness and effective management of stroke, about 80% of patients survive [

6,

7]. Among survivors, almost 50% live with long term disability and consequently with reduced quality of life [

7,

8]. Stroke patients require immediate emergency and acute inpatient care, rehabilitation, home care and outpatient pharmaceutical and medical care which contributes to significant direct health expenditure. Moreover, stroke as a long lasting (sometimes even life lasting) disease is related to increased productivity losses such as work loss (due to deaths and premature retirement), caregiver burden and reduced productivity due to disease [

6]. Consequently, it has major economic impact on the health systems, on communities and families representing one of the largest public health challenges globally. Notably, stroke is no longer considered a disease of the elderly, as each year over 58% of ischemic strokes occur in people younger than 70 years and consequently its societal impact is expected to increase further in the next years [

1].

The total burden of stroke in 2017 worldwide was estimated at

$891 billion [

1]. Based on Fernandez et al., [

8] the overall cost of stroke in 32 European countries in 2017 was estimated at €60 billion and it was projected that the overall cost of stroke may increase up to €75 billion in 2030, €80 billion in 2035 and €86 billion in 2040. Out of €60 billion, 45% was attributed to direct medical expenditure (€27 billion), 27% was spent on the informal, unpaid care (€16 billion), 20% was related to loss of productivity (of people of working age) due to deaths and disability (€12 billion) and 8% was attributed to social care (nursing or residential care) (€5 billion).

In Greece, the total burden of stroke in 2017 was estimated at €650 million from which €284million (43.7%) were spent on direct medical costs and the rest were attributed to loss of productivity, informal/unpaid and social care [

8]. A number of Greek studies have calculated the direct medical cost of stroke focusing on inpatient acute care [

9,

10,

11]. Moreover, a study conducted in 2018 by Vemmos et al. [

12] estimated the total annual economic burden of atrial fibrillation (AF)-related stroke in Greece, from a societal perspective, based on an advisory board consisting of key experts in the management of AF and AF-related stroke. The total annual socioeconomic burden of AF-related stroke was estimated at €175 million, 59% of which was related to direct healthcare cost and 41% to indirect cost. However, no study was found related to the calculation of the burden of stroke all over the cycle of care based on real world data in Greece.

Thus, the aim of this study was twofold: a) to measure one year cost of stroke (direct medical costs, loss of productivity and informal care costs) using a bottom-up approach, using real world data and b) to investigate the value of stroke care, defined as cost per Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis Framework and Study Population

We conducted a bottom-up cost analysis from the societal point of view. All cost components over the cycle of care including direct medical costs, productivity losses due to morbidity and mortality and informal care costs were considered. We used an annual time horizon, including all costs for 2021, irrespective of the time of the disease onset.

The study population (N=892) derived from the “Improving Stroke Care in Greece in Terms of Management, Costs and Health Outcomes - SUN4Patients” project [registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04109612)]. The SUN4P study was a prospective cohort multicenter study of patients with first ever acute stroke, hemorrhagic and ischemic, (ICD-10 codes: I61, I63 and I64) admitted within 48 hours of symptoms onset to nine public hospitals (National Health System and University hospitals), located in six big cities of Greece, from July 2019 to November 2021. (Suppl Figure SΙ).

Detailed data were recorded for each patient (from admission up to three months after discharge), including demographics, clinical characteristics, outcomes and utilization of resources [

13]. Neurological severity on admission was estimated using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (0 to 42) points. One out of three patients were followed-up for 1 year, reporting healthcare resources consumption after discharge (e.g. rehabilitation), loss of productivity (e.g. early retirement) and necessity for home care (provided by both hired health givers and family members).

The mean cost (direct and indirect) was extrapolated (based on country stroke epidemiological data) in order to estimate the national annual burden associated with stroke.

2.2. Direct Healthcare Costs

The major cost components that we took into consideration were: i) in-patient care (including both hospitalization during the first stroke episode and readmissions related to stroke during the follow up), ii) rehabilitation care (both institutional based and outpatient), iii) medication, iv) outpatient visits/follow up and lab tests and v) paid home care. Resources consumption (volume data) was derived from the SUN4Patients Web Platform. Unit costs (e.g. prices of Greek DRGs) were retrieved from publicly available official sources (e.g. Ministry of Health). Moreover, National Organization for Health Care Provision-EOPYY (covering more than 95% of the Greek population) provided health expenditure data related to initial hospitalization and possible re- admissions as well as outpatient pharmaceutical care, medications and rehabilitation. In case of out-of-pocket expenses, data was retrieved from interviews with patients at the point of one year follow up. Prices were assigned to resources use in order to estimate total direct costs.

2.3. Loss of Productivity and Informal Care Cost

The major components that we took into consideration were: i) patients’ loss of productivity due to morbidity (absenteeism from work, early retirement, loss of work) ii) patients’ loss of productivity due to mortality iii) family members loss of productivity due to informal caregiving. To measure loss of productivity due to morbidity and mortality, the human capital approach, was used [

14].

Absence from work (due to morbidity) was measured based on patients’ reported productivity loss at the point of one year follow up via interviews. Loss of productivity due to mortality was measured taking into consideration the age and gender specific number of stroke deaths in order to calculate the working years lost at the time of death (the age of 65 years old was considered to be the usual retirement age).

To estimate the cost of informal home care, the opportunity cost approach was adopted to calculate the value of the informal caregivers’ best alternative use for the time they were caring for their loved ones, which resulted to loss of potential income. All volume data was derived from the patients’ interviews at the point of one year follow up.

The total number of lost working years (either for patients and/or for informal caregivers) were adjusted for the age and gender specific probability of being employed/unemployed [

8] and then multiplied by the average or minimum (in case of retired and unemployed informal caregivers) annual income based on the respective information derived by OECD Health Statistics database (amounting to €16,100 in 2021 for the employed or potentially employed and to €8,050 for the retired and unemployed informal caregivers).

2.4. Quality-Adjusted Life Years

The primary clinical outcome was the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, 0-6) at the point of one year follow up (R0: no symptoms, R1: no significant disability, R2: minimal disability, R3: moderate disability, R4: moderate to severe disability, R5: severe disability and R6: death). Utility values stratified by mRS category were derived from the literature (mRS 0=0.88 utilities; mRS 1=0.74 utilities; mRS 2=0.51 utilities; mRS 3=0.23 utilities; mRS 4=-0.16 utilities; mRS 5= -0.48 utilities; mRS 6=0 utilities) [

15,

16]. QALYs were calculated by multiplying the days of life (in the first 12 months) by the aforementioned utility scores. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables (e.g. gender and type of department where stroke patients’ hospitalized) are presented as numbers (N) and percentages (%), while continuous variables (e.g., age and cost) are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to test the normality of the distribution of the continuous variables. Student’s t-test, ANOVA test, Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to identify differences between variables. All tests of statistical significance were two-tailed, and p-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted with the IBM SPSS 21.0.

2.5. Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Nursing Department (protocol code 277/14.01.2019) and the Scientific Committees of the selected hospitals where the study took place. Individuals were informed verbally and in writing for the purposes of the survey. Informed consent was asked to enroll a patient into the study. All patient data were kept strictly confidential in line to Data Protection Guidelines. Analysis was performed on anonymized data. The SUN4P design was in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and was aligned with the Declaration of Helsinki.

4. Discussion

We conducted a bottom-up cost analysis from the societal point of view to measure the burden of stroke (over the cycle of one year). Τhe analysis was based on real world data collected prospectively in nine public and university hospitals in different Greek cities in the framework of the SUN4P project. Moreover, healthcare resources costs were provided directly by the National Organization for the Provision of Health Care (EOPYY) for the participants, following an agreement with EOPYY.

As far as we know this study was the first cost-of-illness study related to stroke management in Greece over a cycle of 12 months based on real world data, prospectively collected with healthcare costs data provided directly by EOPYY. Another important strength of our study is that loss of productivity data due to morbidity and due to informal healthcare-giving were provided directly from patients or their relatives via interviews (at the point of one year follow up), in accordance to study protocol.

We estimated the total cost of stroke in Greece at €343.1 mil a year in 2021, of which €182.9 (53.3%) referred to direct healthcare cost, representing 1.1% of current health expenditure in 2021, a rate placing Greece in the middle of the European countries (respective rates range from 0.58% to 4.34%) [

8]. Moreover, we found that 46.7% of the economic burden of stroke (€160.22 mil) referred to non – health areas (indirect cost), a figure aligned with the corresponding mean rate of the European countries (47%) [

8].

There is limited evidence from Greece to compare the total cost of stroke (in monetary units) estimated in our study with. In a population-based cost analysis study, conducted to measure the overall health and social costs of stroke in 32 European countries (including Greece) [

8], the overall cost of stroke in Greece was estimated higher (in 2017) when compared to our results, due to differences in the study design. A top-down approach was used in the case of the Fernandez et al study [

8]. Information about self -reported stroke patients (ICD-10 codes I60-I69: n ~ 34,000) resources use on primary, outpatient, emergency, social and informal care was gained via surveys (e.g SHARE database, that consists not a population cohort study and Health Interview Survey 2014), while inpatient care data was retrieved from Eurostat database. In our study, we conducted a bottom-up cost analysis taking into consideration stroke patients (ICD-10 codes: I61, I63 and I64: n=32,000), diagnosed by specialized physicians, resources use and costs based on the SUN4Patients registry and third-party payroll real world data (EOPYY). In addition to this, in the case of the Fernandez et al study [

8], the friction method was applied to calculate loss of productivity (only during the time it takes to replace a worker with another from the pool of the unemployed), taking into account €24,800 yearly earnings for men and €20,500 for women in 2017. In our analysis we used the human capital approach [

14] to measure loss of productivity taking into consideration average annual wages, amounting to €16,100 in 2021 for the employed or potentially employed and to €8,050 for the retired and unemployed informal caregivers, based on the respective OECD Health Statistics.

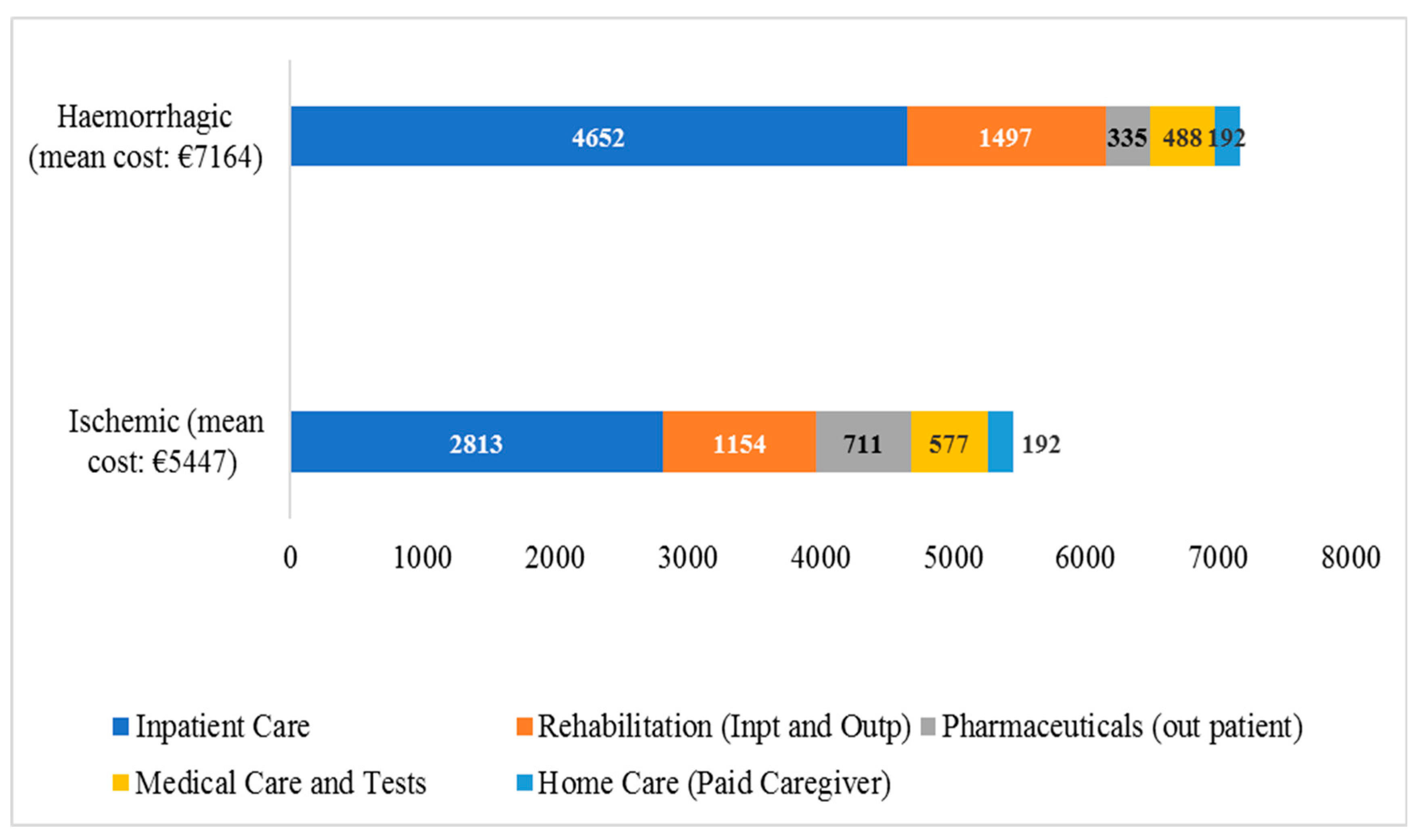

With respect to the allocation of direct healthcare costs, our results are aligned with previous European research [

17] indicating inpatient care as the cost driver. In addition, we found that average hemorrhagic stroke cost was higher when compared to ischemic stroke cost, due to increased health needs of hemorrhagic stroke patients resulting to the provision of longer-term and more intensive healthcare [

18]. For instance, the median length of stay for hemorrhagic stroke patients was increased by 50% when compared to ischemic stroke patients resulting consequently to increased cost of hospitalization. However, in outpatient pharmaceutical care our results reveal that ischemic stroke survivors were in need of increased pharmaceutical care (in order to improve risk factors, control e.g blood pressure, blood glucose, lipid profile etc) for the secondary prevention of stroke recurrence [

19], resulting to increased mean (out-patient) pharmaceutical care cost.

Regarding non- healthcare costs, previous studies have documented the effect of stroke on patients’ and relatives/informal caregivers’ productivity loss [

8,

12,

15], which were confirmed in our analysis. We found substantial productivity loss in the first year following a stroke. Average productivity losses among stroke patients (over the cycle of one year) were estimated at 116 work days. Of note, significant consequences on stroke patients’ families were found, in alignment with previous international and national literature [

20,

21] underlying that “caring for a loved one affected by stroke puts a significant burden on the family caregiver.”[

20]. In particular, we calculated that almost one third of the total productivity loss consisted of informal (unpaid) care costs (i.e about €50 mil., representing 14.5% of total stroke burden), incurred by family members. Increased burden of family members due to caring a stroke patient could be attributed to the lack of nursing homes, insufficient number of rehabilitation centers and help at home programs, in parallel with the Greek tradition of providing home care to chronically-ill and disabled by relatives [

22,

23]. In 2022 a pilot program called "Personal Assistant for people with disabilities" was launched, anticipating to support families of chronically-ill patients.

Also, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study measuring the value of stroke care (defined as cost per QALY) in Greece over the cycle of one year. Thus, we calculated the cost of stroke per QALY at €23,308, a figure that’s equal to 1.44 times the average annual wage in Greece, in 2021, based on the OECD Statistics Database. Even though, there is no evidence from Greece to compare these results with, one recent publication (2023) from New Zealand [

24], with similar to our study population baseline characteristics, provided costs and outcomes data based on a sample of 1,510 acute stroke (elderly) patients. In accordance to this study, the cost per QALY ranged from €34,944 (in case of patients admitted to non-urban hospitals) to €38,064 (in case of patients admitted to urban hospitals) in 2018, figuring almost equal to the average annual wage in New Zealand in 2018 based on the OECD Statistics Database (2023). Thereby, the cost per QALY in Greece is in comparison relatively increased, a finding partially related to the decreased QALYs (gained in Greece) and to potential inefficient organization of stroke care. For the short-term of one year, the average QALYs were estimated at 0.46 (0.38) in Greece, while in case of Kim and al. study [

24] the respective rate ranged from 0.46 (for those patients admitted to non-urban hospitals-40%) to 0.54 (for those patients admitted to urban hospitals-60%), indicating potential gaps to optimal care (in the case of Greece).

Indeed, our results revealed that only a minority of patients (14%) were admitted to a specialized Acute Stroke Unit (ASU), due to the country’s limited availability of ASUs (0.6/million population vs >2/million population in most European countries) [

25]. Moreover, relatively low rates of rtPA administration, 4.6% (in our study) vs. 7.3% the average European rate [

25] were found, that could be attributed to delays from stroke onset to 1st scan, especially increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, when our study was conducted almost simultaneously. Moreover, another obstacle to the provision of rtPA administration, was, in some cases, hospitals’ limited capacity [

11,

26,

27], given the country’s insufficient number of ASUs. In addition, our analysis brought into light gaps of care related to rehabilitation as 1 out of 3 patients participated to an early rehabilitation program during hospitalization and about 13% of survivors were admitted to a rehabilitation center after discharge, although 24.3% of survivors had a mRS=4-5, at the point of discharge. Suboptimal rehabilitative care could probably be attributed to insufficient financing, as less than 1% of the Current Health Expenditure (CHE) in Greece consists of rehabilitative care, while the corresponding rate in most European countries ranges from 2% to 5% of the CHE [

28].

Not surprising, we found that hemorrhagic stroke patients’ average cost per QALY was over doubled compared to the respective rate of ischemic stroke patients. Indeed, hemorrhagic stroke is related to worse functional and clinical outcomes [

29] resulting to decreased QALYs and more costly healthcare compared to ischemic stroke [

17]. Also, increased loss of productivity was reported in case of hemorrhagic stroke patients, as our analysis revealed that out of €160.2 mil., one third was incurred by hemorrhagic stroke patients (who count only 15% of total stroke patients). Indeed, 61.5% of total hemorrhagic stroke burden referred to loss of productivity (vs 41.1% in the case of ischemic stroke) due to increased fatality and severity/disability compared to ischemic stroke [

18].

Our study has some limitations that have to be considered in the extrapolation of the results, as this is not a nationwide registry. Indeed, in our analysis, the study population consisted of stroke patients admitted only to public (NHS and University) hospitals, based on the SUN4Patients protocol. Thereby, our calculations related to direct (mainly out-of-pocket) healthcare expenditure are likely to be underestimated. In accordance to EOPYY data, about 12% of all stroke patients are admitted to private hospitals with a remarkably higher inpatient cost covered mainly by household budgets and/or private insurance. Patients treated in private hospitals (reflecting improved socio-economic profile) are probably willing to pay increased out of pocket payments to ensure faster access to improved healthcare after discharge (e.g rehabilitation, paid home care etc), resulting to higher overall direct healthcare costs. In addition, a recent study aimed to measure the total annual economic burden of atrial fibrillation (AF)-related stroke in Greece [

12] reported that 39% of the direct healthcare costs for stroke was financed by the patients via out-of-pocket expenses, while in our analysis the respective rate was 12%.

Although we recognize this limitation, we underline that policy makers have a lot more influence on publicly funded healthcare services, therefore the most policy impact is expected in this area, which constitutes one of the main reasons why we focused on patients admitted in public hospitals.

Policy Implications

The results of our study highlight the necessity of re-organizing stroke care in Greece, with the full implementation of comprehensive continuous stroke services in order to achieve improved outcomes and thus increased value of care. Indeed, based on the results from a literature review conducted by the European Brain Council Value of Treatment, full implementation of comprehensive stroke services was related with an absolute decrease in risk of death or dependency (by 9.8%) [

30].

In the case of Greece, stakeholders and governmental officials should pay attention in further increasing reperfusion therapies rates

1 and in developing/expanding specialized Acute Stoke Units -ASUs (at least 8-10 over the country), staffed with well trained and dedicated stroke teams [

27]. Although, significant investments are required to ensure these services, current literature indicates their cost-effectiveness.

Previous research [

31,

32,

33,

34] indicates that reperfusion therapy, constitutes a cost-saving or cost-effective treatment option compared to traditional treatment for eligible acute ischemic stroke patients. Moreover, a national cost-effectiveness analysis with data derived from the SUN4Patients registry, concluded that rtPA is a dominant option for the management of eligible stroke patients from the third-party payer perspective, given that it is more effective and costs less than conservative treatment. In particular, rtPA led to 0.009 incremental QALYs per patient in the first 3 months in Greece, with the total cost per patient administered rtPA estimated at €2,196.65, vs. €2,499.45 in the conservative treatment group [

35].

In addition, researchers proved that admission to a specialized ASU is related to improved clinical outcomes and shorter length of stay, compared to conventional treatment in internal medicine or neurological departments, resulting to cost-effectiveness of ASUs [

36]. In Greece, given the country’s geographical disparities, Mobile Stroke Units (MSU) could also contribute to improving the value of care especially in non-urban areas. In accordance to a recently published study from the Norwegian Acute Stroke Prehospital Project, acute ischemic stroke patients’ management, the use of mobile stroke units (MSUs) reduces onset-to-treatment time and increases thrombolytic rates. In addition, there is evidence that MSUs settings are potentially cost-effective compared to conventional care, depending on the annual number of treated patients per MSU (the higher number treated in MSUs, the greater cost-effectiveness gets achieved) [

37].

Finally, gaps in rehabilitation services indicate the necessity to implement effective rehabilitation programs (e.g. timely admission to rehabilitation centers for those patients in need, inpatient rehabilitation), to improve physical functionality and quality of life and thereby to reduce the need for longer term care, resulting to cost constraint. Based on the results of our study, improved mRS at the point of discharge was related to decreased average healthcare cost over the cycle of care. Previous research has proved inpatient rehabilitation as a cost-effective intervention, especially for the partially self-sufficient and moderately disabled stroke patients [

38].

Moreover, taking into consideration the country’s insufficient financing of rehabilitative care due to budget constraints and increased dependency of stroke patients on their family members, which results to significant loss of productivity, alternative interventions, such as home-based rehabilitation, ought to be examined. Based on the results from a study aimed to explore the cost-effectiveness of home-based vs. centre-based rehabilitation in stroke patients across 32 European countries, home-based rehabilitation was found highly likely to be cost-effective (>90%), in the vast majority of the European countries included in the study, a finding confirmed also in the case of Greece [

39].

Author Contributions

Olga SISKOU: study concept, acquisition, methodology, interpretation of data, drafting the article. Petros GALANIS: statistical analysis, drafting the article, critical revision of the manuscript.Olympia KONSTANTAKOPOULOU: statistical analysis, methodology, drafting the article.Panayiotis STAFYLAS: methodology, interpretation of data, drafting the article, critical revision. Iliana KARAGKOUNI: drafting the article, critical revision.Evangelos TSAMPALAS: data collection, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Dafni GAREFOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Helen ALEXOPOULOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Anastasia GAMVROULA: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Maria LYPIRIDOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Ioannis KALLIONTZAKIS: data collection, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Anastasia FRAGKOULAKI: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Aspasia KOURIDAKI: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Argyro TOUNTOPOULOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Ioanna KOUZI: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript; Sofia VASSILOPOULOU: interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Efstathios MANIOS: interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript. Georgios MAVRAGANIS: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Anastasia VEMMOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Efstathia KARAGKIOZI: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Christos SAVOPOULOS: data collection, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Gregorios DIMAS: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Athina MYROU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript; Haralampos MILIONIS: interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript; Georgios SIOPIS: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Hara EVAGGELOU: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Athanasios PROTOGEROU: data collection, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Stamatina SAMARA: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Asteria KARAPIPERI: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.Nikolaos KAKALETSIS: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript.George PAPASTEFANATOS: Software, critical revision of the manuscript.Stefanos PAPASTEFANATOS: Software, critical revision of the manuscript.Panayota SOURTZI: interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.George NTAIOS: Acquisition, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Konstantinos VEMMOS: study concept, acquisition, interpretation of data, drafting the article, critical revision of the manuscript.Eleni KOROMPOKI: study concept, acquisition, interpretation of data, drafting the article.Daphne KAITELIDOU: study concept, methodology, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.