1. Introduction

We assume that the current mathematical knowledge is a finite set of statements from both formal and constructive mathematics, which is time-dependent and publicly available. Any formal theorem of any mathematician from past or present forever belongs to . We assume that mathematical sets are atemporal entities. In this article, they exist formally in theory although their properties can be time-dependent (when they depend on ) or informal.

Let

denote the set of twin primes. The true statement "

There is no known constructively defined integer n such that " is not formal, belongs to

, and may not belong to

in the future. Paul Cohen proved in 1963 that the equality

is independent of

, see [

3]. Before 1963, the false statement "

There is a known constructively defined integer such that " was outside

. Since 1963, this statement is outside

forever. The true statement "

There exists a set such that and never occurred as the winning six numbers in the Polish Lotto lottery" refers to the current non-mathematical knowledge and is outside

.

Algorithms always terminate. We explain the distinction between algorithms whose existence is provable in

and constructively defined algorithms which are currently known. By using this distinction, we obtain non-trivially true statements on decidable sets

that belong to constructive and informal mathematics and refer to the current mathematical knowledge on

. These results are mainly from [

18].

Observation 1 is known from the beginning of computability theory and shows that the predicate of the current mathematical knowledge slightly increases the intuitive mathematics. In Observation 2, the predicate of the current mathematical knowledge trivially increases the constructive mathematics.

Observation 1. Church’s thesis is based on the fact that the currently known computable functions are recursive, where the notion of a computable function is informal.

Observation 2. There exists a prime number p greater than the largest known prime number.

In the traditional Brouwerian intuitionism, the truth of a mathematical statement means that we know a constructive proof, see [

10, p. 135]. Below is the English summary of [

17] available at the internet address of [

17].

The basic philosophical idea of intuitionism is that mathematical entities exist only as mental constructions and that the notion of truth of a proposition should be equated with its verification or the existence of proof. However different intuitionists explained the existence of a proof in fundamentally different ways. There seem to be two main alternatives: the actual and potential existence of a proof. The second proposal is also understood in two alternative ways: as knowledge of a method of construction of a proof or as knowledge-independent and tenseless existence of a proof. This paper is a presentation and analysis of these alternatives.

2. Basic Definitions and Examples

Algorithms always terminate. Semi-algorithms may not terminate. There is the distinction between

existing algorithms (i.e. algorithms whose existence is provable in

) and

known algorithms (i.e. algorithms whose definition is constructive and currently known), see [

2], [

5], [

13, p. 9]. A definition of an integer

n is called

constructive, if it provides a known algorithm with no input that returns

n. Definition 1 applies to sets

whose infiniteness is false or unproven.

Definition 1. We say that a non-negative integer k is a known element of , if and we know an algebraic expression that defines k and consists of the following signs: 1 (one), + (addition), − (subtraction), · (multiplication), ^ (exponentiation with exponent in ), ! (factorial of a non-negative integer), ( (left parenthesis), ) (right parenthesis).

The set of known elements of is finite and time-dependent, so cannot be defined in the formal language of classical mathematics. Let t denote the largest twin prime that is smaller than ((((((((9!)!)!)!)!)!)!)!)!. The number t is an unknown element of .

Definition 2. Conditions (1)-(5) concern sets .

-

(1)

A known algorithm with no input returns an integer n satisfying .

-

(2)

A known algorithm for every decides whether or not .

- (3)

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns the logical value of the statement .

-

(4)

There are many elements of and it is conjectured, though so far unproven, that is infinite.

-

(5)

is naturally defined. The infiniteness of is false or unproven. has the simplest definition among known sets with the same set of known elements.

Condition (3) implies that no known proof shows the finiteness/infiniteness of . No known set satisfies Conditions (1)-(4) and is widely known in number theory or naturally defined, where this term has only informal meaning.

Let denote the integer part function.

Example 1.

does not satisfy Condition (3) because we know an algorithm with no input that computes . The set of known elements of is empty. Hence, Condition (5) fails for .

Example 2. ([

2,

5],([

13]p. 9)).

The function

is computable because or there exists such that

No known algorithm computes the function h.

Example 3.

The set

is decidable. This satisfies Conditions (1) and (3) and does not satisfy Conditions (2), (4), and (5). These facts will hold forever.

3. Number-Theoretic Results

Edmund Landau’s conjecture states that the set

of primes of the form

is infinite, see [

15,

16,

20].

Statement 1. Condition (1) remains unproven for .

Proof. For every set

, there exists an algorithm

with no input that returns

This

n satisfies the implication in Condition (1), but the algorithm

is unknown because its definition is ineffective. □

Statement 2.

The statement

remains unproven in and classical logic without the law of excluded middle.

Statement 3.

The set

satisfies Conditions (2)-(4). Condition (1) fails for , .

Proof. Since

([

16]) and the inequality

remains unproven, Conditions (3) and (4) hold. □

Conjecture 1. ([1,p. 4436]). The are infinitely many primes of the form .

For a non-negative integer n, let denote .

Statement 4.

The set

satisfies Conditions (1)-(5) except the requirement that is naturally defined. . Condition (1) holds with . . 30 .

Proof. For every integer

, 30 is the smallest integer greater than

. By this, if

, then

. Hence, Condition (1) holds with

. We explicitly know 24 positive integers

k such that

is prime, see [

4]. The inequality

remains unproven. Since

, Condition (3) holds. The interval

contains exactly three primes of the form

:

,

,

. For every integer

, the inequality

holds. Therefore, the execution of the following

MuPAD code

m:=0:

for n from 0.0 to 503000.0 do

if n<1!+1 then r:=0 end_if:

if n>=1!+1 and n<2!+1 then r:=1 end_if:

if n>=2!+1 and n<3!+1 then r:=2 end_if:

if n>=3!+1 then r:=3 end_if:

if r>29.5+(11!/(3*n+1))*sin(n) then

m:=m+1:

print([n,m]):

end_if:

end_for:

displays the all known elements of . The output ends with the line , which proves Condition (1) with and Condition (4) with . □

T. Nagell proved in [

11] (cf. [

14, p. 104]) that the equation

has exactly 16 integer solutions, namely

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

. The set

has exactly 23 elements. Among them, there are 14 integers from the interval

. Let

denote the set

From [

16], it is known that

. Hence,

and 14 elements of

can be practically computed. The inequality

remains unproven. The last two sentences and Statement 4 imply the following corollary.

Corollary 1. If we add to , then the following statements hold:

Condition (1) fails for ,

,

the above lower bound is currently the best known,

,

the above upper bound is currently the best known,

satisfies Conditions (2)-(5) except the requirement that is naturally defined.Analogical statements hold, if we add to the set

Definition 3. Conditions (1a)-(5a) concern sets .

-

(1a)

A known algorithm with no input returns a positive integer n satisfying .

-

(2a)

A known algorithm for every decides whether or not .

-

(3a)

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns the logical value of the statement .

-

(4a)

There are many elements of and it is conjectured, though so far unproven, that is finite.

-

(5a)

is naturally defined. The finiteness of is false or unproven. has the simplest definition among known sets with the same set of known elements.

Statement 5.

The set

satisfies Conditions (1a)-(5a) except the requirement that is naturally defined. . Condition (1a) holds with . . 7 .

Proof. For every integer

, 7 is the smallest integer greater than

. By this, if

, then

. Hence, Condition (1a) holds with

. It is conjectured that

is a square only for

, see [

19, p. 297]. Hence, the inequality

remains unproven. Since

, Condition (3a) holds. The interval

contains exactly three squares of the form

:

,

,

. Therefore, the execution of the following

MuPAD code

m:=0:

for n from 0.0 to 1000000.0 do

if n<25 then r:=0 end_if:

if n>=25 and n<121 then r:=1 end_if:

if n>=121 and n<5041 then r:=2 end_if:

if n>=5041 then r:=3 end_if:

if r>6.5+(1000000/(3*n+1))*sin(n) then

m:=m+1:

print([n,m]):

end_if:

end_for:

displays the all known elements of . The output ends with the line , which proves Condition (1a) with and Condition (4a) with . □

Statement 6.

The set

satisfies the conjunction

For a non-negative integer n, let denote the largest integer divisor of smaller than n. Let be defined by setting to be the exponent of 2 in the prime factorization of .

Statement 7.

([18]). The set

satisfies Conditions (1)-(5) except the requirement that is naturally defined. Condition (1) holds with .

Statement 8. There exists a naturally defined set which satisfies the following

Conditions (6)-(11).

-

(6)

A known and simple algorithm for every decides whether or not .

-

(7)

-

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns the logical value of the statement

-

(8)

-

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns the logical value of the statement

-

(9)

It is conjectured, though so far unproven, that is infinite.

-

(10)

-

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns an integer n satisfying

-

(11)

-

There is no known algorithm with no input that returns an integer m satisfying

Proof. Conditions (6)-(11) hold for

. It follows from the following three observations. It is an open problem whether or not there are infinitely many composite numbers of the form

, see [

8] and [

12]. It is an open problem whether or not there are infinitely many prime numbers of the form

, see [

8] and [

12]. Most mathematicians believe that

is composite for every integer

, see [

7]. □

4. A Consequence of the Physical Limits of Computation

Statement 9. No set will satisfy Conditions (1)-(4) forever, if for every algorithm with no input, at some future day, a computer will be able to execute this algorithm in 1 second or less.

Proof. The proof goes by contradiction. We fix an integer

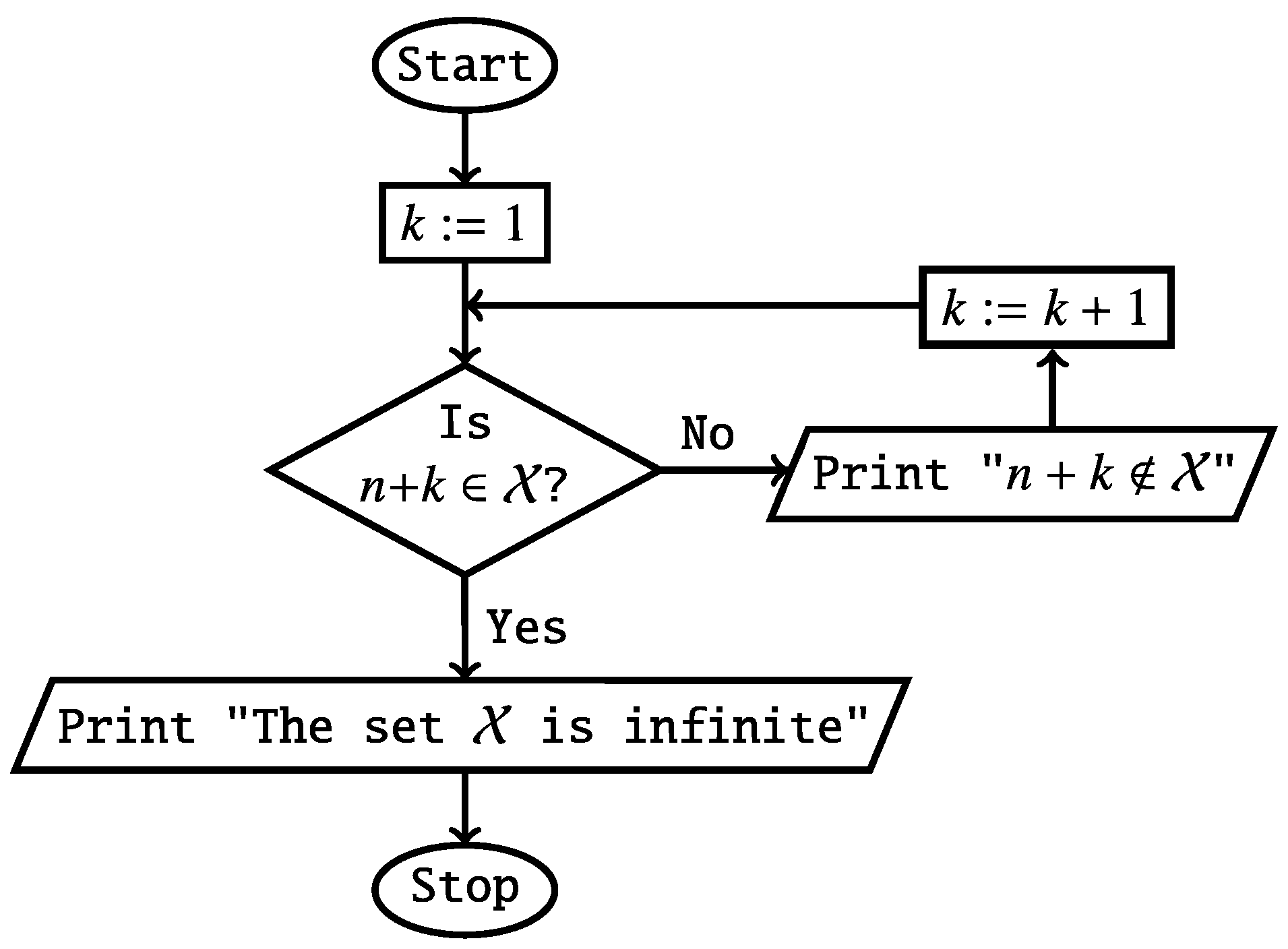

n that satisfies Condition (1). Since Conditions (1)-(3) will hold forever, the semi-algorithm in

Figure 1 never terminates and sequentially prints the following sentences:

The sentences from the sequence (T) and our assumption imply that for every integer computed by a known algorithm, at some future day, a computer will be able to confirm in 1 second or less that . Thus, at some future day, numerical evidence will support the conjecture that the set is finite, contrary to the conjecture in Condition (4). □

The physical limits of computation ([

9]) disprove the assumption of Statement 9.

5. Satisfiable Conjunctions which Consist of Conditions (1)-(5) and Their Negations

Open Problem 1. Is there a set which satisfies Conditions (1)-(5)?

Open Problem 1 asks about the existence of a year

in which the conjunction

will hold for some

. For every year

and for every

, a positive solution to Open Problem

i in the year

t may change in the future. Currently, the answers to Open Problems 1–7 are negative.

The set

satisfies the conjunction

The set

satisfies the conjunction

Let

, and let

for every positive integer

n. The set

satisfies the conjunction

Open Problem 2.

Is there a set that satisfies the conjunction

The numbers

are prime for

. It is open whether or not there are infinitely many primes of the form

, see [

8, p. 158] and [

12, p. 74]. It is open whether or not there are infinitely many composite numbers of the form

, see [

8, p. 159] and [

12, p. 74]. Most mathematicians believe that

is composite for every integer

, see [

7, p. 23]. The set

satisfies the conjunction

Open Problem 3.

Is there a set that satisfies the conjunction

It is possible, although very doubtful, that at some future day, the set will solve Open Problem 2. The same is true for Open Problem 3. It is possible, although very doubtful, that at some future day, the set will solve Open Problem 1. The same is true for Open Problems 2 and 3.

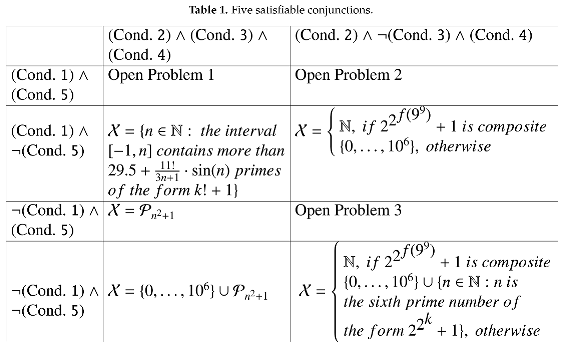

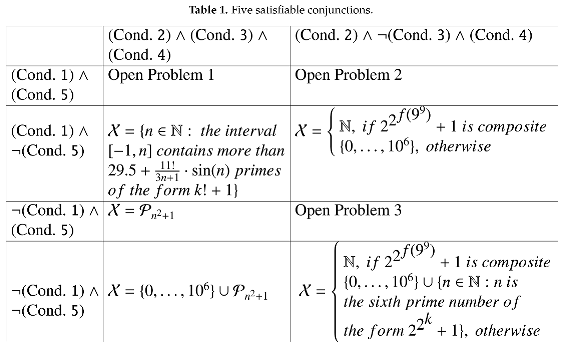

Table 1 shows satisfiable conjunctions of the form

where # denotes the negation ¬ or the absence of any symbol.

6. Subsets of and Their Threshold Numbers

Definition 4. We say that an integer n is a threshold number of a set , if .

If a set is empty or infinite, then any integer n is a threshold number of . If a set is non-empty and finite, then the all threshold numbers of form the set .

Definition 5. We say that a non-negative integer n is a weak threshold number of a set , if .

If a set is infinite, then any non-negative integer n is a weak threshold number of . If a set is finite, then the all weak threshold numbers of form the set .

Example 4.

The set

conjecturally equals . No effectively computable integer n is a threshold number of . No effectively computable non-negative integer n is a weak threshold number of .

Open Problem 4. Is there a known threshold number of ?

Open Problem 5. Is there a known weak threshold number of ?

Open Problem 6. Is there a known threshold number of ?

Open Problem 7.

Is there a known weak threshold number of ?

References

- C. K. Caldwell and Y. Gallot, On the primality of n!±1 and 2×3×5×⋯×p±1, Math. Comp. 71 (2002), no. 237, 441–448. [CrossRef]

- J. Case and M. Ralston, Beyond Rogers’ non-constructively computable function, in: The nature of computation, Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., 7921, 45–54, Springer, Heidelberg, 2013, http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-39053-1_6.

- Continuum hypothesis, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuum_hypothesis.

- Factorial prime, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factorial_prime.

- How can it be decidable whether π has some sequence of digits?, http://cs.stackexchange.com/questions/367/how-can-it-be-decidable-whether-pi-has-some-sequence-of-digits.

- Is n!+1 often a prime?,http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/853085/is-n-1-often-a-prime.

- J.-M. De Koninck and F. Luca, Analytic number theory: Exploring the anatomy of integers, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2012.

- M. Křížek, F. M. Křížek, F. Luca, L. Somer, 17 lectures on Fermat numbers: from number theory to geometry, Springer, New York, 2001,. [CrossRef]

- S. Lloyd, Ultimate physical limits to computation, Nature 406 (2000), 1047–1054. [CrossRef]

- E. Martino, Intuitionistic proof versus classical truth: The role of Brouwer’s creative subject in intuitionistic mathematics, Springer, 2018, http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-74357-8.

- T. Nagell, Einige Gleichungen von der Form ay2+by+c=dx3, Norske Vid. Akad. Skrifter, Oslo I (1930), no. 7.

- P. Ribenboim, The little book of bigger primes, 2nd ed., Springer, New York, 2004.

- H. Rogers, Jr., Theory of recursive functions and effective computability, 2nd ed., MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1987.

- W. Sierpiński, Elementary theory of numbers, 2nd ed. (ed. A. Schinzel), PWN – Polish Scientific Publishers and North-Holland, Warsaw-Amsterdam, 1987.

- N. J. A. Sloane, The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, A002496, Primes of the form n2+1, http://oeis.org/A002496.

- N. J. A. Sloane, The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, A083844, Number of primes of the form x2 + 1 < 10n, http://oeis.org/A083844.

- Z. Tworak, O pojęciu prawdy w intuicjonizmie matematycznym (in Polish) (On the notion of truth in mathematical intuitionism), Filozofia Nauki (Philosophy of Science) 18 (2010), no. 4, 49–76, http://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=269240.

- A. Tyszka, Statements and open problems on decidable sets X⊆N that contain informal notions and refer to the current knowledge on X, Creat. Math. Inform. 32 (2023), no. 2, 247–253, http://semnul.com/creative-mathematics/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/creative_2023_32_2_247_253.pdf.

- E. W. Weisstein, CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics, 2nd ed., Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 2002.

- Wolfram MathWorld, Landau’s Problems, http://mathworld.wolfram.com/LandausProblems.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).