1. Introduction

Cytokines, secretary proteins molecules, are pivotal players in various biological processes including proliferation, growth, and immune regulation across both vertebrates and invertebrates [

1,

2,

3]. Most of the cytokines are involved with the Janus kinase (JAK) and the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) pathways, which are known to play an essential role in immune responses [

4]. Accumulating evidence suggests the presence of a number of JAKs and STATs in vertebrates including humans and fish, and their possible regulation by these molecules [

5,

6]. Hence, tight control of cytokines is vital for maintaining immune homeostasis. Consequently, various molecules have been identified that act as physiological suppressors and restrain the excessive activities of cytokines. Among them, the suppressor of cytokine signaling molecules (SOCS) hold particular significance as the “key negative regulators” of these molecules [

7].

The SOCS family of vertebrates comprises 8 members, namely SOCS1–7 and cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CISH) [

8,

9]. Based on the available evolutionary analysis data, two distinctive SOCS groups have been identified as type II with SOCS1–3 and CISH and type I with SOCS4–7. All SOCS members share common structural features, including a C-terminal SOCS box and a centralized SH2 domain [

1,

8,

9]. Meanwhile, their N terminal regions exhibit variability which is believed to be associated with their specific functions. For instance, SOCS1 and SOCS3 have a unique N- terminal domain, kinase inhibitory region (KIR), which is essential for the suppression of the JAK tyrosine kinase activity [

10,

11]. The SOCS4 and SOCS5 contain a conserved region in their N terminal (N-terminal conserved region-NLTR) which has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling [

12,

13]. Interestingly, SOCS6 and SOCS7 do not have any of these specifications in their respective N-terminal regions [

14].

Despite the well-documented immune regulatory activities of SOCS genes in vertebrates, their functions in invertebrates, particularly the type I SOCS, remain relatively undiscovered. As such, several research efforts have been directed toward understanding the role of SOCS in the immune regulation of invertebrates. The first identified invertebrate SOCS was SOCS-36E, in fruit fly (

Drosophila melanogaster) revealed it has similar characteristics and functional significance to the human SOCS5, in regulating the JAK-STAT pathway [

15]. Subsequent studies unrevealed 2 additional SOCS genes in

D. melanogaster, named SOCS44A and SOCS16D, which displayed sequence similarities (33-34% and 45-48%) to the human SOCS6 and SOCS7, with the potential regulatory capabilities in the JAK-STAT pathway [

16]. In reference to crustaceans, the role of SOCS6 in the Chinese mitten crab (

Eriocheir sinensis) was recently elucidated, highlighting its involvement in the mediation of both JAK-STAT and NF-κB (nuclear factor-kappa B) pathways [

14]. Additionally, in the Pacific oyster (

Crassostrea gigas), three SOCS genes (SOCS2, SOCS5, SOCS7) have been identified, exhibiting potential in the regulation of NF-κB transcription [

17]. Furthermore, the expression and functional implications of SOCS2 (belongs to the type II SOCS family) in the innate immune responses of red swamp crayfish and white leg shrimp (

Procambarus clarkii and

L. vannamei) have been investigated following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and/or bacterial challenges [

18,

19]. These studies conveyed the importance of SOCS genes in the immune defense mechanisms of crustaceans.

However, despite the growing body of research on invertebrate SOCS, there is a notable knowledge gap regarding the presence and function of type I SOCS genes in shrimp. The present study aims to address this gap by investigating the presence of type I SOCS genes (LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7) in white-leg shrimp. The mRNA expression levels of identified SOCS upon post-immune stimulations and their possible association with the JAK-STAT signaling pathway was investigated, expanding our understanding of the immune regulatory mechanisms of SOCS in crustaceans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Shrimp rearing and tissue collection

One-month-old healthy juvenile white leg shrimps, L. vannamei (body weight, BW = 0.9 ± 0.1 g; body length, BL = 1.8 ± 0.2 cm), were purchased from a commercial shrimp farm in Muan-gun, Jeollanam-do, South Korea. All shrimps were transported alive to the laboratory of Pukyong National University and reared in a recirculating aquarium tank (width × depth × height = 1.0 m × 3.0 m × 0.5 m) equipped with sponge-filtered and UV-sterilized seawater. Shrimps were fed four times per day with a commercially formulated shrimp diet (Jeil Feed. Co., Ltd) on an ad libitum basis. The rearing tank was maintained under continuous aeration (dissolved oxygen, DO = 9.7± 0.2 mg/L) with an ambient temperature of 24 ± 1 °C and pH of 7.6 –7.8. Water chemical parameters were measured once a day, and the concentrations of ammonia (NH3), nitrites (NO2-), and nitrates (NO3-) were maintained at 0.25-0.5 mg/L, 0.25 mg/L, and 20-40 mg/L, respectively, to ensure the optimal rearing conditions. The white leg shrimp (L. vannamei) grown to BW of 3.0 ± 0.5 g and BL of 2.5 ± 0.3 cm were used in all experiments. To isolate hemocytes, shrimp hemolymph was drawn from the ventral region above the first abdominal segment using a sterilized syringe preloaded with a commercial anticoagulant (Alsever’s solution, A3551, Sigma Aldrich, USA) in a 1:1 ratio, and then immediately centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Tissues were harvested by dissection. All the tissue samples were stored in RNAlater solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) at -80 °C until use. Specific approval by the local institution/ethics committee was not required for the present study using invertebrate crustaceans and all experiment procedures were strictly conducted according to the guideline for the care and use of laboratory animals by the Animal Ethics Committee of Pukyong National University.

2.2. Immune challenge

The reared shrimps were randomly distributed into four 40 L experimental tanks with 4 groups, including three immune challenge groups and a control group, each containing 30 shrimps. For immune challenge experiments, 10 µL of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli 0111: B4, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and peptidoglycan (PGN) (Staphylococcus aureus, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) suspended in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 100 mg/mL were injected into the shrimp abdominal segments Ⅲ and Ⅳ. As the control group, an equal volume of PBS was injected. Tissues (gill, heart, muscle, and stomach) were pooled from three shrimps randomly sampled at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-injections (hpi) and stored in RNAlater solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) at -80 °C until use. The immune challenge experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from RNAlater-stored tissues using an RNA extraction kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) including the DNA elimination step. Quantity and quality of the obtained total RNA were assessed using a spectrophotometer using Nanophotomer NP 80 (Implen, Munich, Germany) and the ratios of both 260 nm/280 nm and 260 nm/230 nm were confirmed to be at least higher than 1.9. Complementary DNA was synthesized through reverse transcription with oligo dT (dT18) using AccuPower® RT PreMix (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The synthesized cDNA was stored at -80 °C for subsequent experiments.

2.4. Cloning of LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7 cDNA

The nucleotide sequences for

L. vannamei SOCS6 and SOCS7 (designated as

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7) were firstly obtained from a homology search against the NCBI shrimp transcriptome shotgun assembly (TSA) database using orthologs proteins,

EsSOCS6 (accession number: ATW63847.1) from the Chinese mitten crab (

E. sinensis) and

TmSOCS7 (accession number: QDL52635.1) from the Mealworm beetle (

Tenebrio molitor), as queries [

14,

20]. For

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 a single set of primers was designed based on the retrieved TSA sequences (accession numbers: GETZ01043689.1 and GETZ01051062.1). (

Table S1). PCR was performed using cDNA obtained from the hepatopancreas of 3 individuals as a template according to the following procedures: a cycle of 94 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30, and 72°C for 1 to 3 mins; and an extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The targeted PCR product was cloned into pTOP TA V2 vector (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) and verified by sequencing.

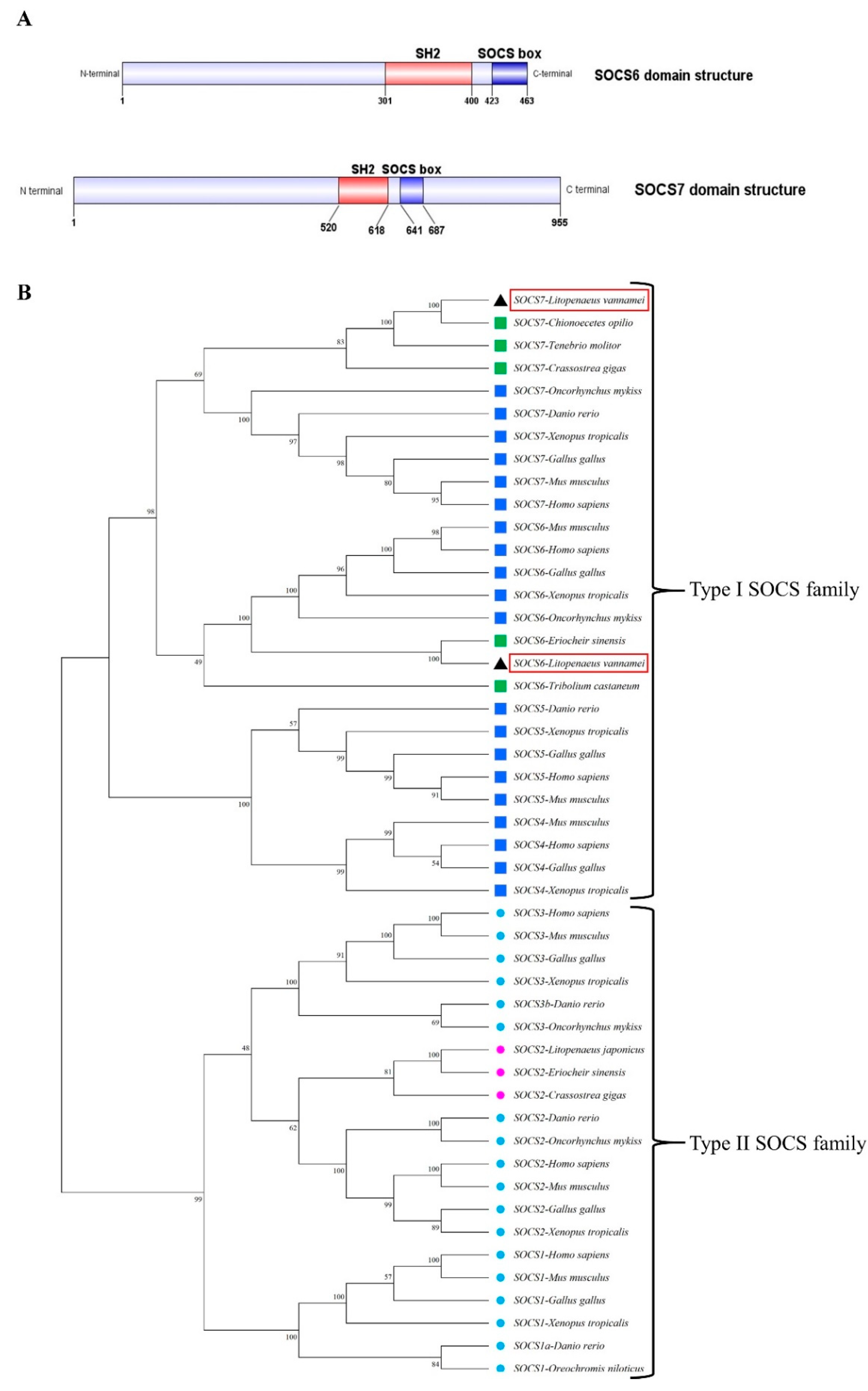

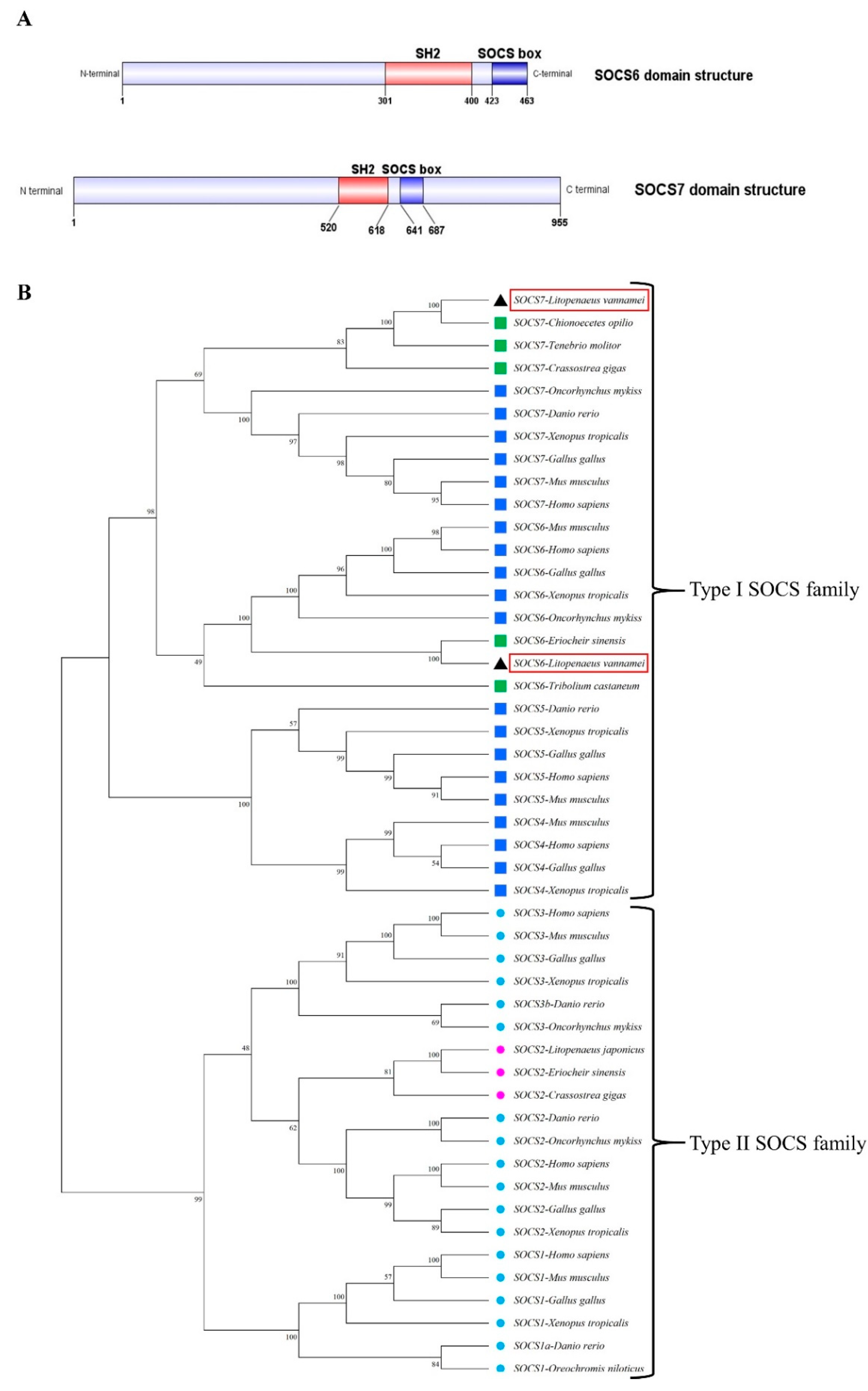

2.5. In silico sequence analysis and molecular phylogeny

The protein sequences of

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 were deduced from the cloned sequences using the NCBI open reading frame (ORF) finder (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) [

21]. Domain architectures were visualized by Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) (

http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and CDD blast program (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) [

22,

23]. Molecular weights and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) values of each

LvSOCS were identified using the ExPASy pI/Mw tool (

https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) [

24]. Multiple sequence alignments of

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 with ortholog SOCSs were conducted using Clustal Omega (

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) and refined manually [

25]. In order to elucidate the evolutionary relationships between

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 and other homologs, molecular phylogeny was analyzed using full-length representative protein sequences in vertebrates and invertebrates available in the NCBI database. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using maximum likelihood (ML) methods with MEGA software (ver. 10.0.5;

https://www.megasoftware.net/). The Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model was employed as a substitution model. The confidence of tree topology was tested with 1,000 bootstrap replicates [

26].

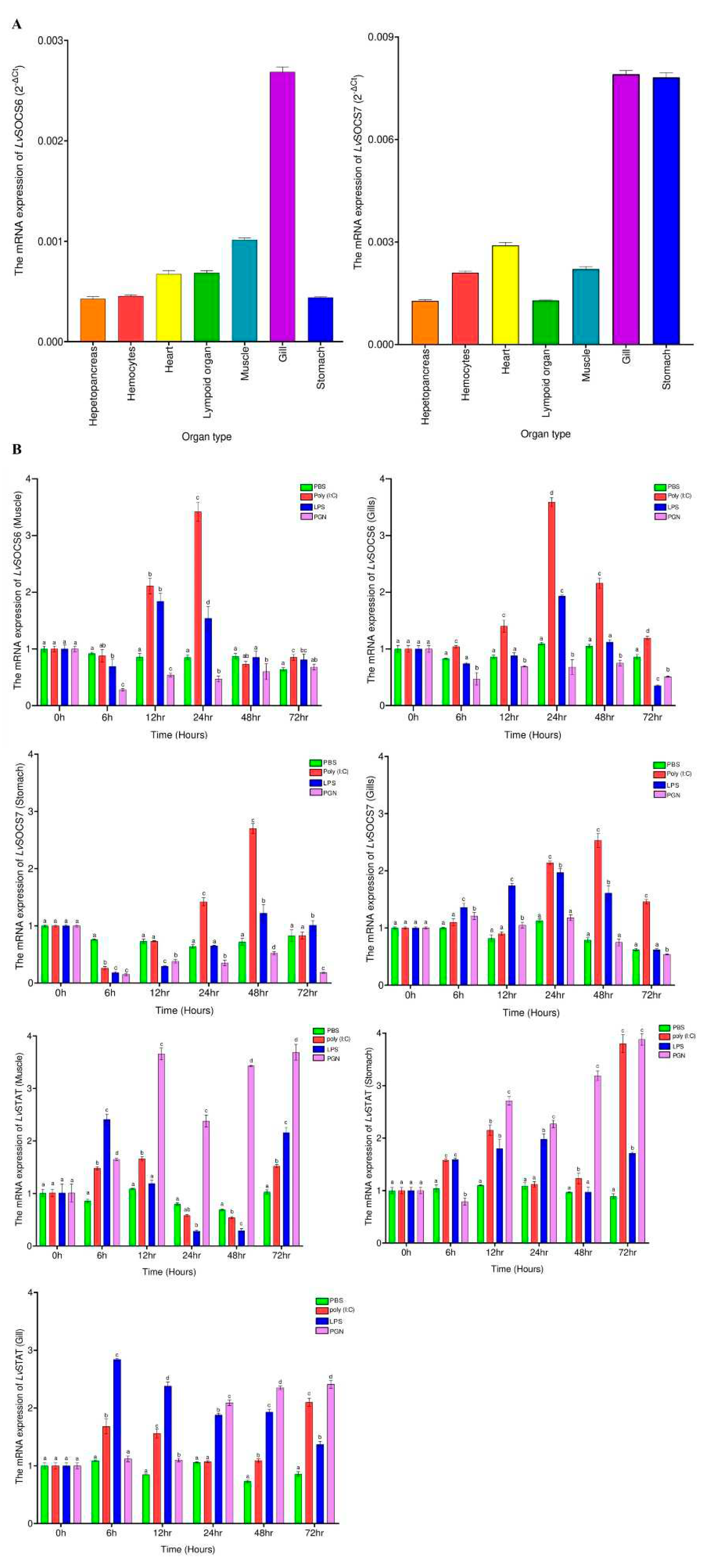

2.6. Tissue distribution and expression pattern analysis

The tissue distribution of

LvSOCS mRNAs was analyzed in triplicate in 7 tissues (gill, heart, hemocytes, hepatopancreas, lymphoid organs, muscle, and stomach) that were obtained by pooling from 3 individuals. Based on the results of the tissue distribution analysis, only the tissues (muscle, stomach, heart, and gill) with relatively high mRNA expression of

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 were selected for analysis of expression patterns changes following immune challenge. In addition, the expression patterns of STAT gene (GeneBank accession number: HQ228176.1) in

L. vannamei were also examined in order to show the possible interconnection with the JAK-STAT signaling pathway according to changes in the mRNA expression patterns of

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 following immune challenge. To determine tissue distribution and expression changes in response to immune challenge, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was carried out using a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Germany) with SYBR green premix (TOPreal qPCR 2X PreMix, Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea). The primer pairs used for amplifying

LvSOCS6,

LvSOCS7,

LvSTAT, and elongation factor 1α (EF1α) cDNA as a control for normalization were listed in

Table S1. Relative expression was estimated based on the normalization of the expression level of each

LvSOCS6,

LvSOCS7, and

LvSTAT to EF1α expression using the 2

-ΔΔCT method [

27].

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data were presented as means ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis for RT-qPCR data was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) supported by Turkey multiple comparison test using SPSS software (Version 25). P values less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) were considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Cytokines, the secreted polypeptide molecules, exert significant influence over a myriad of biological processes encompassing cellular proliferation, growth, and immune regulation in both vertebrates and invertebrates [

2,

8,

19,

20]. Among the diverse array of molecules involved in cytokine signaling, the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) molecules possess noteworthy significance due to their crucial role as principal antagonists of these signaling mediators [

7]. Within the SOCS gene family, a dichotomy emerges, comprising the type II SOCS and type I SOCS groups (consisting of SOCS1, SOCS2, SOCS3, SOCS4, SOCS5, SOCS6, and SOCS7) [

1,

8,

12]. In contrast, the presence and comprehensive characterization of these SOCS genes, and their immunoregulatory involvement in vertebrates has reached to a well-documented stage. Nonetheless, the existence and potential functionalities of SOCS genes in invertebrates, particularly within the domain of crustaceans, lack substantive evidence. Within the confines of this investigation, two previously unreported type I SOCS genes were successfully identified in the popular food crustacean “white leg shrimps”, designated as

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7. The characterized

LvSOCS genes in the present study exhibited the archetypal, centrally localized Src homology 2 (SH2) domain region, concomitant with the C-terminal suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-box domain. Furthermore, there were 3 distinct motifs, encompassing the phosphotyrosine binding, hydrophobic binding, and putative elongin B/C binding, which are renowned for their involvement in mediating protein-protein interactions and modulating diverse signaling pathways [

28,

29]. Additionally, the investigation of phylogenetic relationships among SOCS proteins provided valuable insights into their evolutionary history and functional diversification of these identified

LvSOCS. We employed the maximum likelihood method to construct a phylogenetic tree, which integrated a comprehensive set of SOCS protein sequences from both vertebrate and invertebrate organisms. The resulting phylogenetic tree uncovered significant topological distinctions, giving rise to 2 major lineages as type I-SOCS and type II-SOCS. Within the type II-SOCS lineage, further differentiation was observed, manifesting as distinct sub-branches that corresponded to specific members of the SOCS1, SOCS2, and SOCS3. Similarly, the type I-SOCS lineage exhibited its own differentiation, generating representative sub-branches associated with SOCS4, SOCS5, SOCS6, and SOCS7. Thus it suggests that SOCS proteins have undergone lineage-specific evolutionary changes, and emphasizes the divergent evolutionary trajectories and their unique functional attributes [

8]. Importantly, our analysis also included the

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 identified in this study, which were assigned to the invertebrate SOCS6 and SOCS7 groups in the phylogeny. The placement of

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 within their respective invertebrate sub-branches of the phylogenetic tree supports their classification and highlights their evolutionary relationships with other known SOCS proteins.

In white leg shrimps, the identified

LvSOCS mRNAs exhibited a pervasive presence across all analyzed tissues, showcasing noteworthy fluctuations in expression levels. These dynamic variations potentially might be aligned with the multifaceted biological functionalities intrinsic to shrimps. Comparable observations have been discerned in other invertebrate organisms, such as the Chinese mitten crab, where distinct levels of

EsSOCS6 gene expression were detected in the hepatopancreas and hemopoietic tissues, displaying differential patterns of higher and lower expression [

14]. Likewise, in mealworms,

TmSOCS6 expression had its peak in hemocytes, whereas

TmSOCS7 expression elevated in Malpighian tubules [

20]. Akin to these findings, the silk moth (

B. mori) exhibited heightened

BmSOCS6 expression within the fat body in contrast to other tissues [

30]. In the realm of vertebrates, such as fish species, the expression profiles of SOCS genes have also been observed to fluctuate across different tissue types. For example, in rainbow trout (

O. mykiss),

OmSOCS6 expression levels showcased variation in the skin and gills [

31]. In our investigation, both

LvSOCS genes manifested significant expression in the gills, with the intriguing discovery that

LvSOCS7 exhibited prominent expression levels also in the stomach. These fascinating findings tentatively suggest the potential existence of distinct and organ-specific roles fulfilled by the identified

LvSOCS genes, necessitating further experimental validation and confirmation.

The JAK/STAT signaling cascade plays a pivotal role in orchestrating immune responses across the animal kingdom, primarily driven by an array of cytokines [

4,

14]. Extensive research has elucidated the significance of type I SOCS genes in vertebrates, notable examples include the involvement of SOCS7 in the translocation of the STAT3 gene, a critical transcriptional regulator of IFN-β and interleukin 6 in humans [

32]. Furthermore, investigations have unveiled potential connections between the JAK/STAT pathway and neural cell differentiation in humans, with SOCS6 emerging as an essential participant in these intricate processes [

33]. In reference to invertebrates, studies involving

d. melanogaster has shed light on the regulatory role of SOCS36E, SOCS44A, and SOCS16D (analogous to SOCS5, SOCS6, and SOCS7) in dampening the JAK-STAT pathway by influencing its regulation [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the current body of knowledge regarding the involvement of type I SOCS genes in the JAK/STAT pathway of crustaceans remains limited, warranting further investigation, to unravel their contributions within this extensive signaling network. Hence, to further explore the regulatory association of

LvSOCS and

LvSTAT genes, we investigated their mRNA expression in response to the administration of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including poly(I:C), LPS, and PGN. These PAMPs are known to induce inflammatory and immune regulatory responses (mimicking the activities of viruses, gram negative and/or gram positive bacteria), activating key signaling pathways such as JAK-STAT and NF-kB [

19,

31,

34]. Additionally, they are commonly employed as stimulants to study immune response patterns. In our comprehensive investigation, intriguing observations emerged when examining the intricate interplay between

LvSOCS6,

LvSOCS7, and

LvSTAT gene expression dynamics. First, our immune stimulation experiments revealed a significant increase in

LvSOCS expression following poly(I:C) and LPS administration peaking at or after 12 hours, but not following the PGN administration. However, the highest significant increase in

LvSOCS6 and

LvSOCS7 expression was observed in poly(I:C) administrated group (3.59 and 2.7-fold), reinforcing that these identified genes might have enhanced sensitivity to viral infections than bacterial infections. Secondly, the conspicuous downregulation of

LvSOCS expression coincided with the upregulation of

LvSTAT mRNA levels. Although the precise temporal pattern of this response was not uniform across all assessed time points, it unequivocally implies a noteworthy correlation between diminished

LvSOCS expression and the modulation of

LvSTAT gene activity. It is important to acknowledge that other members of the SOCS gene family, such as

LvSOCS2, have also been implicated in the multifaceted JAK/STAT pathway, thereby potentially contributing to the current regulatory network at play [

19]. Moreover, given the existing evidence elucidating the involvement of type I SOCS genes in the NF-кB pathway, a comprehensive exploration of their sophisticated roles within the immune machinery of crustaceans becomes imperative, necessitating in-depth investigations to unravel their precise contributions [

14,

17]. Consequently, understanding the regulatory mechanisms of SOCS genes and their involvement in immune pathways will significantly augment our comprehension of crustacean immunology and make notable contributions to the wider domain of invertebrate immune modulation.

Figure 1.

(A) The domain architectures of LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7. The predicted SH2 and SOCS-box positions are shown in red and blue color boxes respectively. (B) Mega software-based maximum likelihood tree of 48 SOCS protein sequences among vertebrates and invertebrates. The numbers at tree nodes refer to the percent bootstrap values following 1000 replications. The species and the GenBank accession numbers used for the phylogenetic analysis were as follows: The type I family includes SOCS1 from D. rerio (NP_001003467.1), H. sapiens (NP_003736.1), M. musculus (NP_034026.1), G. gallus (NP_001131120.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001011327.1), O. niloticus (NP_001297020.1), SOCS2 from D. rerio (XP_005164804.1), H. sapiens (NP_001257400.1), M. musculus (NP_031732.1), G. gallus (NP_989871.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001120898.1), O. niloticus (XP_036813373.1), C. gigas (EKC24772.1), L. japonicus (BAI70368.1), E. sinensis (ACU42699.1), SOCS3 from D. rerio (NP_998469.1), H. sapiens (NP_003946.3), M. musculus (NP_031733.1), G. gallus (NP_001186037.1), X. tropicalis (XP_031746340.1), O. mykiss (NP_001139640.1), SOCS4 from H. sapiens (NP_659198.1), M. musculus (NP_543119.2), G. gallus (NP_001186037.1), X. tropicalis (XP_031746340.1). The type II family includes SOCS5 from H. sapiens (NP_955453.1), M. musculus (NP_062628.2), G. gallus (NP_001120786.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001016844.1) and D. rerio (ABM68036.1). SOCS6 from H. sapiens (NP_004223.2), M. musculus (NP_061291.2), G. gallus (NP_001120784.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001096240.1), O. mykiss (NP_001182102.1), E. sinensis (ATW63847.1), L. vannamei* (SOCS6-OR030046), T. castaneum (XP_008190646.1), SOCS7 from H. sapiens (NP_055413.2), M. musculus (NP_619598.2), G. gallus (XP_040509254.1), X. tropicalis (XP_012827004.2) D. rerio (XP_009304138.1) O. mykiss (CAP17279.1), T. molitor (QDL52635.1), C. gigas (AKA59677.1), Chionoecetes opilio (KAG0725835.1) and L. vannamei* (SOCS7- OR030047). The blue colors indicate vertebrate species, purple and green colors indicate invertebrates, and the red box highlights the newly identified SOCS6/SOCS7 for L. vannamei.

Figure 1.

(A) The domain architectures of LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7. The predicted SH2 and SOCS-box positions are shown in red and blue color boxes respectively. (B) Mega software-based maximum likelihood tree of 48 SOCS protein sequences among vertebrates and invertebrates. The numbers at tree nodes refer to the percent bootstrap values following 1000 replications. The species and the GenBank accession numbers used for the phylogenetic analysis were as follows: The type I family includes SOCS1 from D. rerio (NP_001003467.1), H. sapiens (NP_003736.1), M. musculus (NP_034026.1), G. gallus (NP_001131120.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001011327.1), O. niloticus (NP_001297020.1), SOCS2 from D. rerio (XP_005164804.1), H. sapiens (NP_001257400.1), M. musculus (NP_031732.1), G. gallus (NP_989871.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001120898.1), O. niloticus (XP_036813373.1), C. gigas (EKC24772.1), L. japonicus (BAI70368.1), E. sinensis (ACU42699.1), SOCS3 from D. rerio (NP_998469.1), H. sapiens (NP_003946.3), M. musculus (NP_031733.1), G. gallus (NP_001186037.1), X. tropicalis (XP_031746340.1), O. mykiss (NP_001139640.1), SOCS4 from H. sapiens (NP_659198.1), M. musculus (NP_543119.2), G. gallus (NP_001186037.1), X. tropicalis (XP_031746340.1). The type II family includes SOCS5 from H. sapiens (NP_955453.1), M. musculus (NP_062628.2), G. gallus (NP_001120786.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001016844.1) and D. rerio (ABM68036.1). SOCS6 from H. sapiens (NP_004223.2), M. musculus (NP_061291.2), G. gallus (NP_001120784.1), X. tropicalis (NP_001096240.1), O. mykiss (NP_001182102.1), E. sinensis (ATW63847.1), L. vannamei* (SOCS6-OR030046), T. castaneum (XP_008190646.1), SOCS7 from H. sapiens (NP_055413.2), M. musculus (NP_619598.2), G. gallus (XP_040509254.1), X. tropicalis (XP_012827004.2) D. rerio (XP_009304138.1) O. mykiss (CAP17279.1), T. molitor (QDL52635.1), C. gigas (AKA59677.1), Chionoecetes opilio (KAG0725835.1) and L. vannamei* (SOCS7- OR030047). The blue colors indicate vertebrate species, purple and green colors indicate invertebrates, and the red box highlights the newly identified SOCS6/SOCS7 for L. vannamei.

Figure 2.

(A) The tissue distribution patterns of LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7 in different tissues following qPCR analysis. The data is expressed using the 2 (-ΔCt). (B) The temporal mRNA expression analysis of LvSOCS6 (Muscle, Gills) LvSOCS7 (Stomach, Gills), and LvSTAT (Muscle, Stomach, and Gills) following challenge experiments with LPS, poly (I:C), PGN, or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All the qPCR data were normalized to EF1α internal control gene. Results are represented as the mean ± S.E (N = 3). Statistically significant values (P < 0.05) are denoted with alphabets.

Figure 2.

(A) The tissue distribution patterns of LvSOCS6 and LvSOCS7 in different tissues following qPCR analysis. The data is expressed using the 2 (-ΔCt). (B) The temporal mRNA expression analysis of LvSOCS6 (Muscle, Gills) LvSOCS7 (Stomach, Gills), and LvSTAT (Muscle, Stomach, and Gills) following challenge experiments with LPS, poly (I:C), PGN, or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All the qPCR data were normalized to EF1α internal control gene. Results are represented as the mean ± S.E (N = 3). Statistically significant values (P < 0.05) are denoted with alphabets.