1. Introduction

Among the diseases that affect ruminants, disorders of the central nervous system (CNS) cause numerous losses, especially rabies and botulism [

1]. However, other conditions, such as bovine herpesvirus type 5 and polioencephalomalacia (PEM), deserve mention. In this context, PEM is a descriptive term that means necrosis with softening (malacia) of the gray matter (polio) of the brain [

2,

3], and the use of this term can be confusing, as it can be used to designate the laminar necrosis lesion of the cerebral cortex, which is seen in sodium chloride intoxication and sulfur, lead poisoning and bovine herpesvirus type 5 encephalitis, as well as in specific neurological disease in ruminants associated with disturbances in thiamine (vitamin B1) metabolism [

3,

4].

It is a condition that affects the CNS of animals causing neurological signs associated with different structures of the brain. In the early stages, flaccidity is common, although there may be transient periods of spasticity and intermittent chronic seizures, with muscle tremors, especially of the head, and intermittent to permanent opisthotonos. In severe cases with longer evolution of PEM, the animals become prostrate, with ear, eyelids, and facial spasms, empty intermittent chewing, teeth grinding, sialorrhea, hyperexcitability, and aggressiveness [

5,

6].

At necropsy, there is encephalic edema, pallor, and softening of the cerebral hemispheres and flattening of the cerebral gyri, with herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum and extensive gray matter malacia areas [

4,

5,

6]. The diagnosis of PEM is based on epidemiological, clinical-pathological, and histopathological findings and, in some cases, on the clinical response to thiamine and corticoid treatment [

7].

PEM was initially described in the State of Colorado, USA, in cattle and sheep with neurological disorders in which the etiology was attributed only to thiamine deficiency, later being attributed to a multifactorial characteristic for the disease [

2,

8]. In Europe, the same lesion pertinent to PEM was called cerebrocortical necrosis [

8] and in Canada, there are reports of the disease even in llama [

9]. In Brazil, PEM has been described bovines [

10,

11,

12], ovine [

13,

14,

15], goats [

13,

14,

16] and only one case in buffaloes in the State of Mato Grosso, Midwest region of Brazil [

17].

Thus, considering the low number of PEM references in buffaloes, the objective of the present work is to report five PEM cases in buffaloes, four in the state of Pará and one in the state of Amapá, region of the Brazilian Amazon Biome.

2. Materials and Methods

The study comprised five buffaloes (01 to 05). Epidemiological data such as age, sex, race, farm location, and breeding systems were obtained at the clinical visit. Animals with clinical signs compatible with polioencephalomalacia were submitted to the general and specific clinical examination of the nervous system as established by Dirksen et al. [

18]. Necropsy was performed on the five animals. During the necropsy, the location and intensity of the lesions were evaluated and organ fragments were collected, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and sent to the Pathological Anatomy Sector of the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro for histopathological examination. Tissue samples were routinely processed, embedded in paraffin, cut at 5µm, and stained using the hematoxylin and eosin technique (H&E), according to the methodology described by Luna [

19]. All animals included in the study were negative for rabies and botulism, which are the main differential diagnoses of neurological disease in ruminants [

20]. This research was authorized by the animal experimentation ethics committee (CEUA) of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) under protocol number 6261300323 (ID 002208).

3. Results

The diagnosis of the five PEM buffaloes was based on epidemiological, clinical-pathological and histopathological studies, this being the first report of the disease in the Amazon Biome. Of the five studied animals, all were of the Murrah breed, four male and one female, with ages ranging from two months to one year, two buffaloes (buffalo 01 and 02) were from the municipality of Castanhal, Pará, kept in an extensive breeding system on Urochloa brizantha pasture. Buffaloes 03 and 04 belonged to a property located in the municipality of Cachoeira do Arari, Marajó Island, Pará, and buffalo 5 was from a property located in the municipality of Itaubal, state of Amapá, all of them were raised in an extensive system in flooded of native pasture.

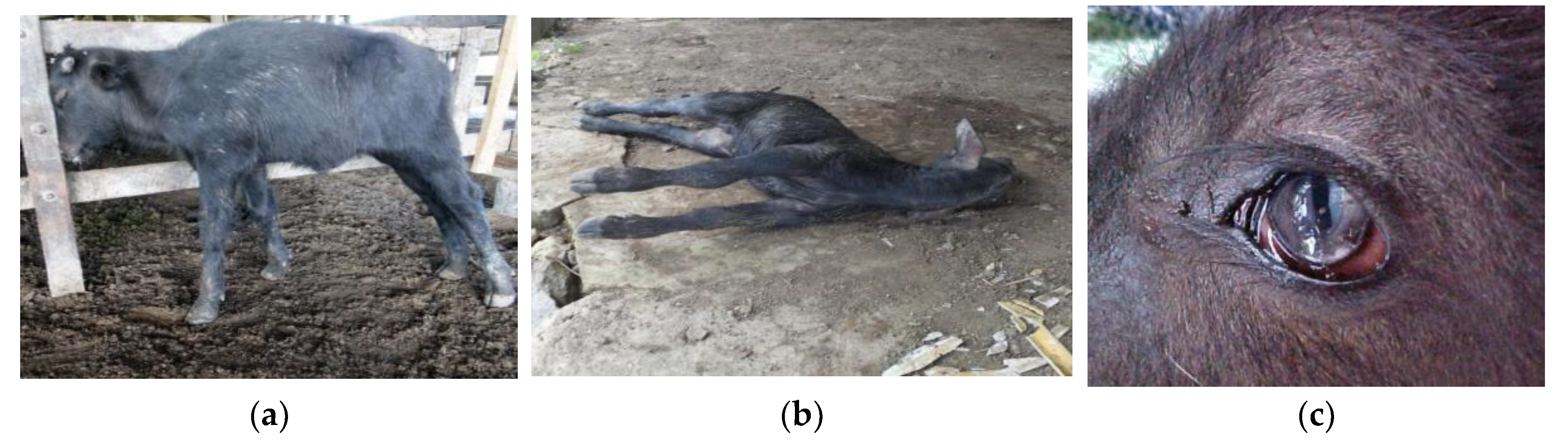

At the clinical examination, all buffaloes had a body score between 2.5 and 3 (scale from 1 to 5). Buffaloes 03 and 04 were still standing at the clinical examination, and there was noted decreased alertness, postural changes, marked hypermetria when wandering, blindness demonstrated by colliding to the corral structures, head pressing (

Figure 1A), and hindlimbs circumduction when supported on the forelimbs. These two buffaloes evolved to lateral decubitus and, as the other three buffaloes (01, 02 and 05), who were found in lateral decubitus at the clinical visit, and also presented opisthotonos (

Figure 1B), muscle tremors, convulsions, paddling movements, sialorrhea and decrease in palpebral and pupillary reflexes. Additionally, in buffaloes 01 and 05 there was seen a rotation of the eyeball, placing the pupillary slit in a vertical position (cat pupil) (

Figure 1C).

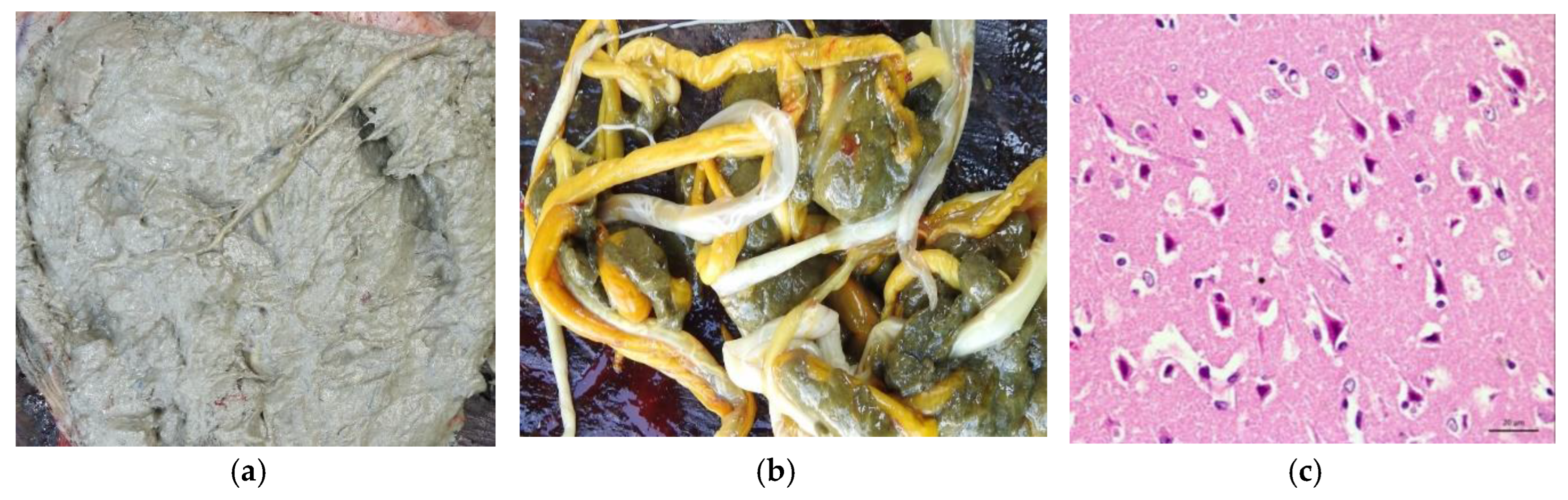

In terms of clinical course, all animals died between three and five days after the clinical sign’s onset. Posteriorly, at necropsy, mild lesions characterized by edema and flattening of the cerebral convolutions were evidenced. In addition to the alterations observed in the brain, in buffalo 01 and 05, the contents of the rumen had a pasty appearance, with a “grease appearance” resulting from a mixture of mud and plant material (

Figure 2A) and large number of parasites also in the rumen (

Figure 2B). Histopathological findings showed laminar necrosis of the cerebral cortex (

Figure 2C).

4. Discussion

Due to the scarce literature referring to PEM in buffaloes, there were considered as a reference for the discussion studies carried out in cattle, goats, and sheep.

The age of the animals studied, which ranged from two months to one year, as well as Withoeft et al. [

12], who diagnosed PEM in calves from 15 days to one-year-old ages. This can be explained by primary thiamine deficiency, as these animals are still young and are not able to produce it or ingest it in insufficient quantity [

8,

21]. Furthermore, according to Dal Mas et al. [

7] PEM does not show seasonality with foci occurring in all months of the year in Mato Grosso do Sul, a fact that also occurred in Australia, USA and Great Britain, therefore, the tropical climate of the Amazon region is not a determining factor for occurrence or not of PEM in buffaloes, demonstrating that PEM can also occur in this climate.

Guimarães et al. [

17] diagnosed PEM in buffaloes in the leguminous pasture, that is evidenced by the possibility of PEM emergence in buffaloes breed in different types of pastures. Moro et al. [

22] also reported cases of polioencephalomalacia in cattle with sudden changes in feeding from poor to excellent pasture and generally young animals on high concentrate diet are at high risk [

23] a fact that did not occur in buffaloes in the outbreaks studied.

The clinical signs were of a multifocal nature, involving all regions of the brain (brain, cerebellum, and brainstem), similar to the clinical signs referred to cattle [

10,

11,

12], sheep [

13] and goats [

14,

16]. In light of this symptomatology, Riet-Correa et al. [

5], refer that the results from the increase in intracranial pressure exerted by the edema of the brain structures, which often causes herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum.

The death of buffaloes between the third and fifth day after the appearance of symptoms demonstrates an acute evolution of this disease in buffaloes, consistent with Sampaio et al. [

6], which referred to the evolution of PEM from a few hours to four days.

The intensity of the lesions could be due to the acute clinical course, since Riet-Correa et al. [

5] report that necropsy findings vary according to the severity and duration of the clinical condition. Commensurate with the literature, the lesions are discrete, swelling and there is a decrease in brain consistency in animals with an acute clinical course, as observed in this study [

3]. Furthermore, due to cerebral edema, caudal displacement (herniation) of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum may occur [

3,

5]. In chronic cases, in which the animals survive for several days, necrosis becomes more evident and the brain is visibly reduced in size due to the loss of gray matter, with flattening of the convolutions, yellowish gelatinous consistency areas of the cortex, and cavitations [

5,

6]. Laminar necrosis of the cerebral cortex has also been found in cattle with PEM [

10,

12,

24] and in sheep for Lima et al. [

13] intoxicated with sulfur.

The ruminal content found in buffalo 01 and 05 is considered an unsuitable environment for bacterial activity. As ruminants are dependent on the synthesis of thiamine by ruminal bacteria, it leads us to assume that in this ruminal environment found, thiamine production was insufficient to meet the needs of the animal, not ruling out this condition in triggering the disease [

2,

21]. The active form of thiamine is thiamine pyrophosphate, a cofactor of transketolase, which in turn regulates the pentose phosphate pathway responsible for a large part of the ATP used in nerve cells [

8], a fact that explains the triggering of thiamine. of clinical signs of PEM in the absence of thiamine. In addition, sulfur intoxication cannot be ruled out either, which also leads to lesions found in PEM conditions in which ruminal bacteria are involved, transforming ingested sulfur sulfates into the toxic form that are sulfides that can affect cellular respiration [

12,

21].

Regarding the differential diagnosis, it is important to consider diseases that cause laminar necrosis of the cerebral cortex, such as lead poisoning, encephalitis due to bovine herpes virus type 5, and salt intoxication [

3]. However, all the animals were raised in an extensive system and did not receive mineral supplementation or have access to sources of lead, which excludes the possibility of salt or lead poisonings. Additionally, in encephalitis by herpesvirus type 5, common histopathological findings are extensive areas of malacia in the telencephalon cortex, with possible intranuclear inclusion bodies in astrocytes and neurons [

25,

26,

27] what was not observed in the studied animals.

Taking into account the most frequent diseases, rabies was ruled out by epidemiological data, as the disease only affected young buffalo calves, and by histopathological findings such as the absence of the Negri corpuscle in the CNS tissue and the presence of CNS gray matter necrosis, which is not correlated to rabies [

28]. Likewise, botulism was also ruled out by epidemiology, as this intoxication is not common in suckling calves and the common clinical signs such as flaccid paralysis was not observed in the group of studied buffaloes [

29].

As a perspective on the disease in buffaloes, it was not possible to establish the cause of PEM in the animals studied, which demonstrates the real need for descriptive and pathophysiological studies of the disease in buffaloes, mainly in the Amazon region, which has all the epidemiological factors favorable to its occurrence. of the disease.

5. Conclusions

This study is the first to explore polioencephalomalacia in buffaloes in the Amazon biome. The diagnosis of PEM was based on epidemiological, clinical-pathological, and histopathological findings, which were similar to findings in other ruminants. The cause of PEM in the studied buffaloes was not established, which indicates the need for further studies to elucidate this disease in the species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.S., M.F.B., F.M.S.M., C.E.d.S.F.F. and J.D.B.; methodology, C.C.B., E.V.V., R.P.d.L.S, M.F.B., and J.D.B.; formal analysis, C.T.d.A.L , N.d.S.e.S.S., C.M.C.O., M.F.B., F.M.S. and J.D.B.; investigation, F.M.S.M., C.E.d.S.F.F., C.C.B., E.V.V., R.P.d.L.S., N.d.S.e.S.S., and J.D.B.; data curation, F.M.S., M.F.B., F.M.S.M., C.E.d.S.F.F., C.T.d.A.L , N.d.S.e.S.S., C.M.C.O., and J.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.S., M.F.B., F.M.S.M., C.E.d.S.F.F., C.T.d.A.L , N.d.S.e.S.S., C.M.C.O., and J.D.B..; writing—review and editing, F.M.S., M.F.B., and J.D.B.; supervision, F.M.S. and J.D.B.; project administration, F.M.S., C.M.C.O., and J.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas do Estado do Pará), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Finance Code 001), and PROPESP-UFPA (Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Universidade Federal do Pará) for funding the publication of this article via the Programa Institucional de Apoio à Pesquisa—PAPQ/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol number 6261300323 (ID 002208) was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Para (CEUA/UFPA) in the meeting of 04/27/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas do Estado do Pará), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Finance Code 001), and PROPESP-UFPA (Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Universidade Federal do Pará) for funding the publication of this article via the Programa Institucional de Apoio à Pesquisa—PAPQ/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mello, A.K.M.; Brumatti, R.C.; Neves, D.A.; Alcântara, L.O.B.; Araújo, F.S.; Gaspar, A.O.; Lemos, R.A.A. Bovine rabies: economic loss and its mitigation through antirabies vaccination. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2019, 39, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jense, R.; Griner, L.A.; Adams, O.R. Polioencephalomalacia of cattle and sheep. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1956, 129, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Assis, J.R.; Assis, A.C.M.; Nunes, D.; Carlos, A.B. Nutritional and food aspects related to polioencephalomalacy in ruminant. Scient. Eletr.c Arch. 2020, 13, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radostits, O.M.; Clive, C.G.; Blood, D.C.; Hinchcliff, K.W. Clínica Veterinária. Um Tratado de Doenças Dos Bovinos, Ovinos, Suínos, Caprinos e Equinos, 9th ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Riet-Correa, F.; Riet-Correa, G.; Schild, A.L. Importância do exame clínico para o diagnóstico das enfermidades do sistema nervoso em ruminantes e eqüídeos. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2002, 22, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, P.H.; Fidelis Junior, O.L.; Marques, L.C.; Cadiolli, F.A. Polioencefalomalácia em ruminantes. Rev. Inv. Med. Vet. 2015, 14, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Mas, F.E.; Bär, M.M.; Guirro, E.C.B.P. Polioencefalomalácia por deficiência de tiamina em ruminantes – revisão bibliográfica. Rev. Ciên. Vet. Saúde Púb. 2017, 4, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Vitor, T.L.; Wilson, T.M.; Souza, D.E.R.; Leonardo, A.S.; Silva, V.L.D.; Saturnino, K.C.; Vulcani, V.A.S. Polioencefalomalacia em ruminantes: aspectos etiológicos, clínicos e anatomopatológicos. Rev. Cient. Med. Vet. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Himsworth, C.G. Polioencephalomalacia in a llama. Can. Vet. J. 2008, 49, 598–600. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato, L.; Lemos, R.A.A.; Riet-Correa, F. Polioencefalomalacia em bovinos nos estados de Mato Grosso do Sul e São Paulo. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2000, 20, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.C.N.; Borges, A.S.; Peiró, J.R.; Feirosa, F.L.F.; Anhesini, C. R Retrospective study of 19 cases of polioencephalomalacia in cattle, responsive to the treatment with thiamine. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2007, 59, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withoeft, J.A.; Bonatto, G.R.; Melo, I.C.; Hemckmeier, D.; Costa, L.S.; Cristo, T.G.; Pisetta, N.L.; Casagrande, R.A. Polioencephalomalacia (PEM) in calves associated with excess sulfur intake. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2019, 39, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.F.; Riet-Correa, F.; Tabosa, I.M.; Dantas, A.F.M.; Medeiros, J.M.; Sucupira Júnior, G. Polioencephalomalacia in goats and sheep in the semiarid region of northeastern Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2005, 25, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, H.; Soares, L.L.S.; Oliveira Cruz, J.A.L.; Souto, P.C.; Botelho Ono, M.S.; Costa, J.H.M.; Mendonça, F.S.; Honório de Melo, L.E.; Guimarães, J.A.; Dantas, A.C. Polioencefalomalacia em pequenos ruminantes atendidos no ambulatório de grandes animais da Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife-PE. Scientia Plena 2015, 11, 1–8. https://www.scientiaplena.org.br/sp/article/view/2473.

- Nascimento, k.A.; Ferreira Junior, J.A.; Novais, E.P.F.; Perecmanis, S.; Sant’Ana, F.J.F.; Pedroso, P.M.O.; Macêdo, J.T.S.A. Polioencephalomalacia in Newborn Lamb. Acta Sc. Vet. 2020, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, L.R. Polioencefalomalácia em caprinos: oito relatos de caso. Rev. Acad. Ciên. Anim. 2017, 15, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, E.B.; Lemos, R.A.A.; Nogueira, A.P.A.; Souza, A.C. Ocorrência natural de polioencefalomalácia em búfalos Murrah (Buballis bubalis), mantidos em pastagem de gramínea consorciada com leguminosa em fase de rebrota, em MS. Anais. Encontro Nacional de Diagnóstico Veterinário Campo Grande, MS. 2008, 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen, G.; Gründer, H.D.; Stöber, M. Medicina Interna y Cirurgía del Bovino, 4 rd. ed; Editora Inter-médica: Buenos Aires, 2005; pp. 618–629. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, L. G. Manual of histologic staining methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 3rd ed.; Blakiston Division, Mcgraw-hill: Nova York, 1968; 258 p. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, G.R.; Oliveira, R.A.M.; Flaiban, K.K.M.C.; Di Santis, G.W.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L.; Headley, S.A.; Alfieri, A.A.; Lisbôa, J.A.N. [Differential diagnosis of neurologic diseases of cattle in the state of Paraná. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38, 1264–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, P.; Riquelme, P.; Reyes, C. Effect of rumen protected thiamine on blood concentration of beta-hydroxyl butyrate in postpartum Holstein cows: a pilot study. Rev. Ciên. Vet. 2022, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, L.; Nogueira, R.H.; Carvalho, A. U.; Marques, D.C. Report of three cases of polioencephalomalacia in bovine. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 1994, 46, 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, S.; Agrawal, R.; Rashid, S.M. Diagnosis and Management of polioencephalomalacia in Indian buffaloes under farm conditions. Buffalo Bulletin. 2011, 30, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, P.H.J.; Bandarra, P.M.; Dias, M.M.; Borges, A.S.; Driemeier, D. Outbreak of polioencephalomalacia in cattle consuming high sulphur diet in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, A.W.D.; Langohr, I.M.; Stigger, A. L.; Barros, C.S.L. Diseases of the central nervous system in cattle of southern BrazilPesq. Vet. Bras. 2000, 20, 113–118. [CrossRef]

- Colodel, M.E.; Nakazato, L.; Weiblen, R.; Mello, R.M.; Silva, R.P.; Souza, M.A.; Oliveira, J.A.; Caron, L. Necrotizing meningo-encephalitis in cattle due to bovine herpesvirus in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Ciên. Rur. 2002, 32, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Ana, F.J.F.; Lemos, R.A.A.; Nogueira, A.P.A.; Togni, M.; Tessele, B.; Barros, C.S.L. Polioencephalomalacia in ruminants. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2009, 29, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.F.; Riet-Correa, F.; Castro, R.S.; Gomes, A.A.B.; Lima, F.S. Clinical signs, Clinical signs, distribution of the lesions in the central nervous system and epidemiology of rabies in northeastern Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2005, 25, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvarani, F.M.; Otaka, D.Y.; Oliveira, C.M.C.; Reis, A.S.B.; Perdigão, H.H.; Souza, A.E.C.; Brito, M.F.; Barbosa, J.D. Type C waterborne botulism outbreaks in buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in the Amazon region. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).