Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

01 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of LTP ST Paraffin with Nano-Additives

2.2. Test Apparatus and Methodology

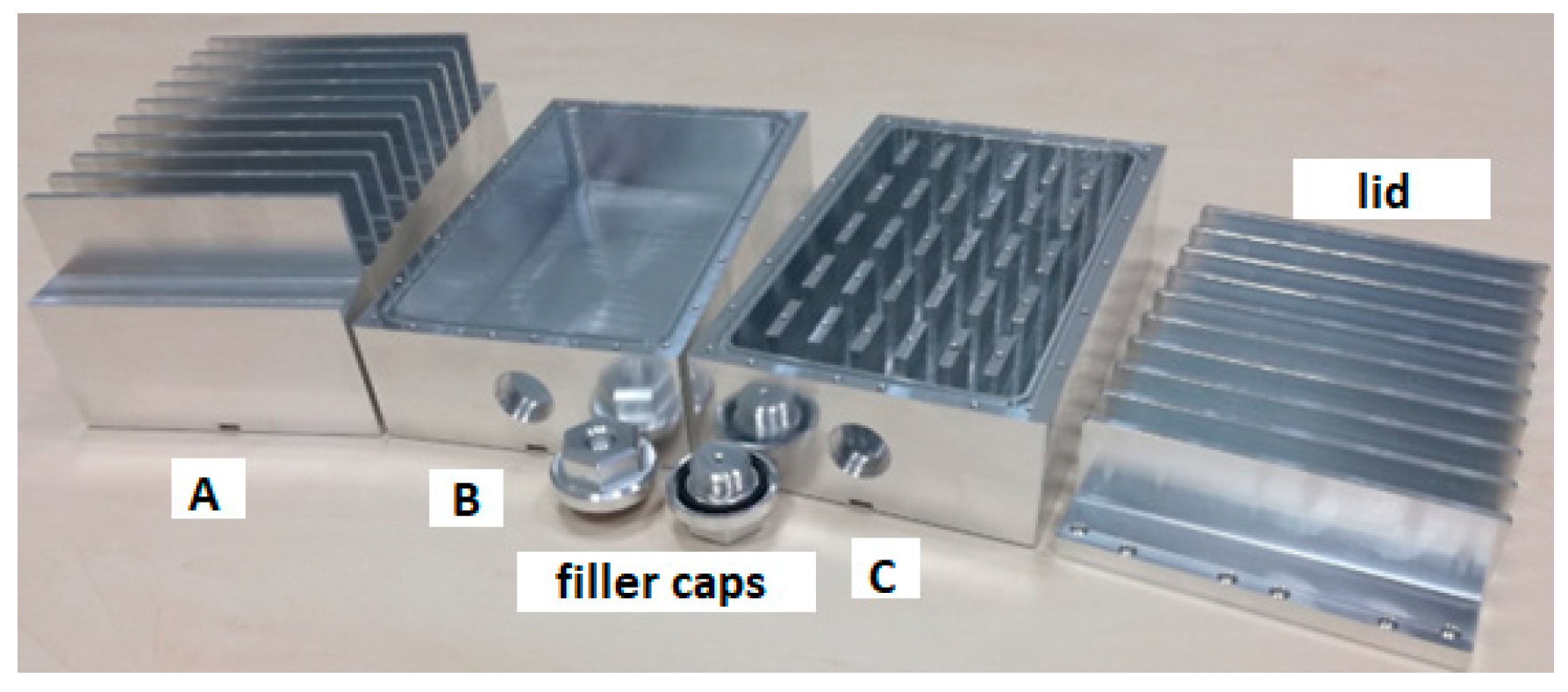

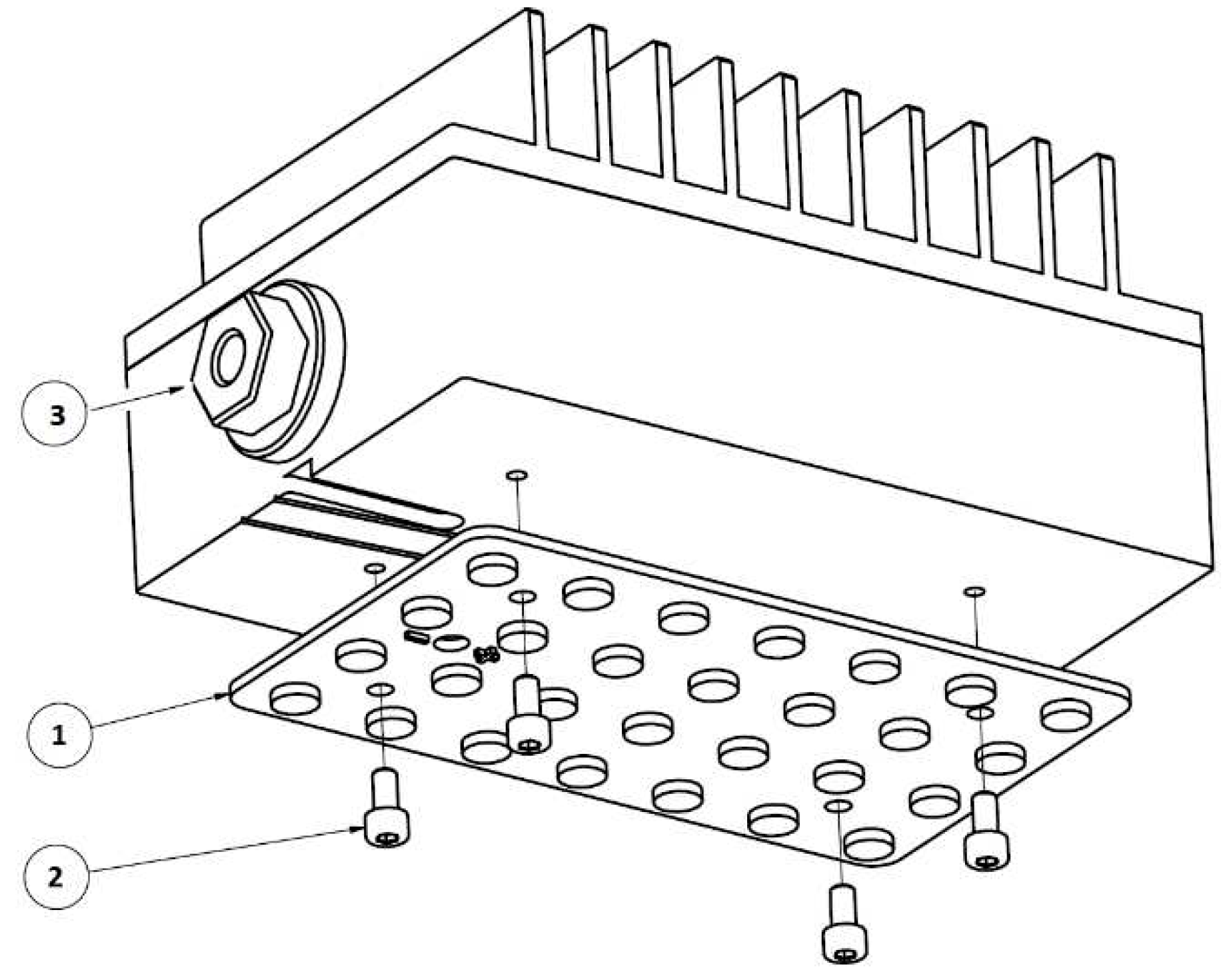

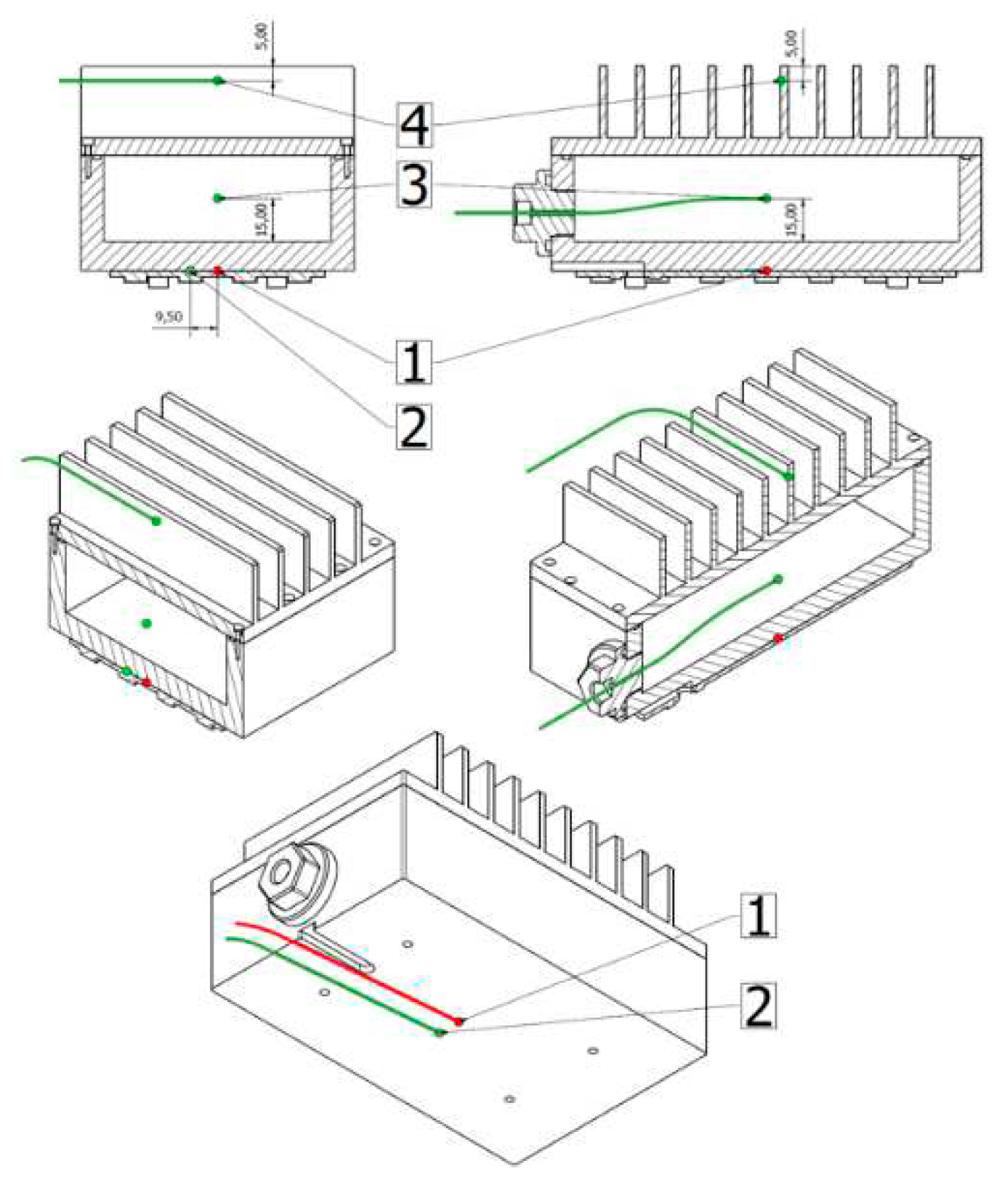

3. Passive Cooling System Design

3.1. Measurement System and Data Acquisition

4. Results and Discussion

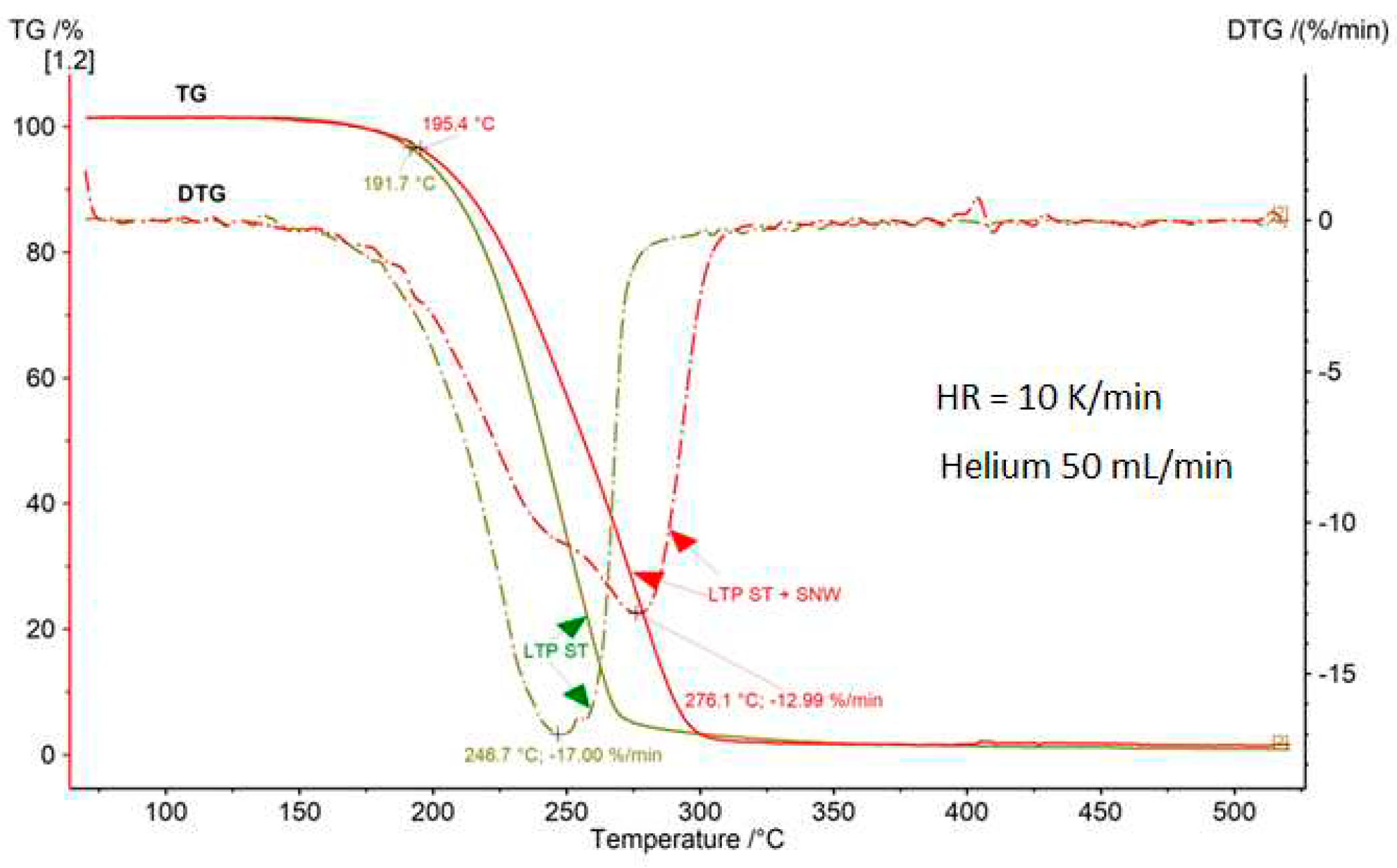

4.1. Results of Measurements of Thermophysical Properties

4.2. Experimental Results of the Passive Cooling System

- ✓

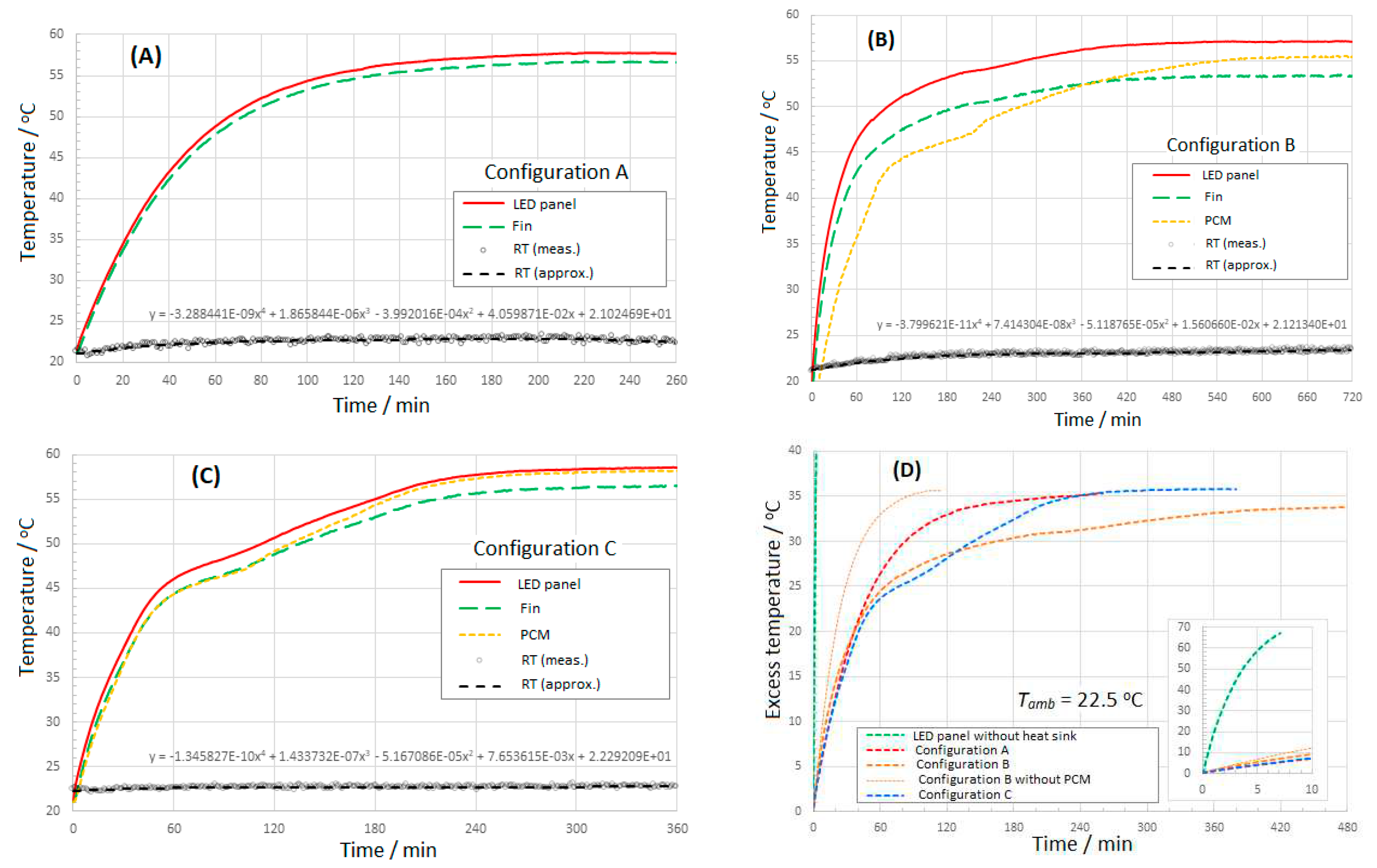

- The cooling system in configuration A is characterized by a compact design, which translated into a relatively low thermal resistance compared to other designs with PCM chambers. The temperature difference between the LED panel and the measurement point located on the side surface of the fin (at state state) averaged 1.1.

- ✓

- Equipping the system (heat sink) with a paraffin-filled chamber (configuration B) increased the thermal stabilization time of the working system from 260 min up to 480 min, i.e. by 185% compared to configuration A. There was also a decrease in the maximum excess temperature of the LED panel by 4.4% compared to configuration A. The temperature difference between the LED panel and the fin increased to 3.7 This increase is a consequence of the higher thermal resistance at the interface of the LED panel and the fin. This is due to the fact that the the effective thermal conductivity of the chamber containing the PCM for configuration B is significantly lower than the thermal conductivity of the solid AW2017A material used to build the heat sink in configuration A.

- ✓

- Configuration C has a 127% longer thermal stabilization time compared to system A. The temperature difference between the LED panel and the fin was 2.1. The use of fins inside the PCM chamber improved the heat transfer to the phase change material and to the lid with external fins. This is evidenced by a direct comparison of configurations B and C with configuration A, which shows lower surface temperatures for the LED panel in configuration C in the first 130 min of operation. In the longer term, the heat sink in configuration B, with more PCM material, gains the advantage. The PCM chamber of C-system was reduced by the volume of in-chamber fins, which was 18.7% of the original volume of the B-system chamber.

- ✓

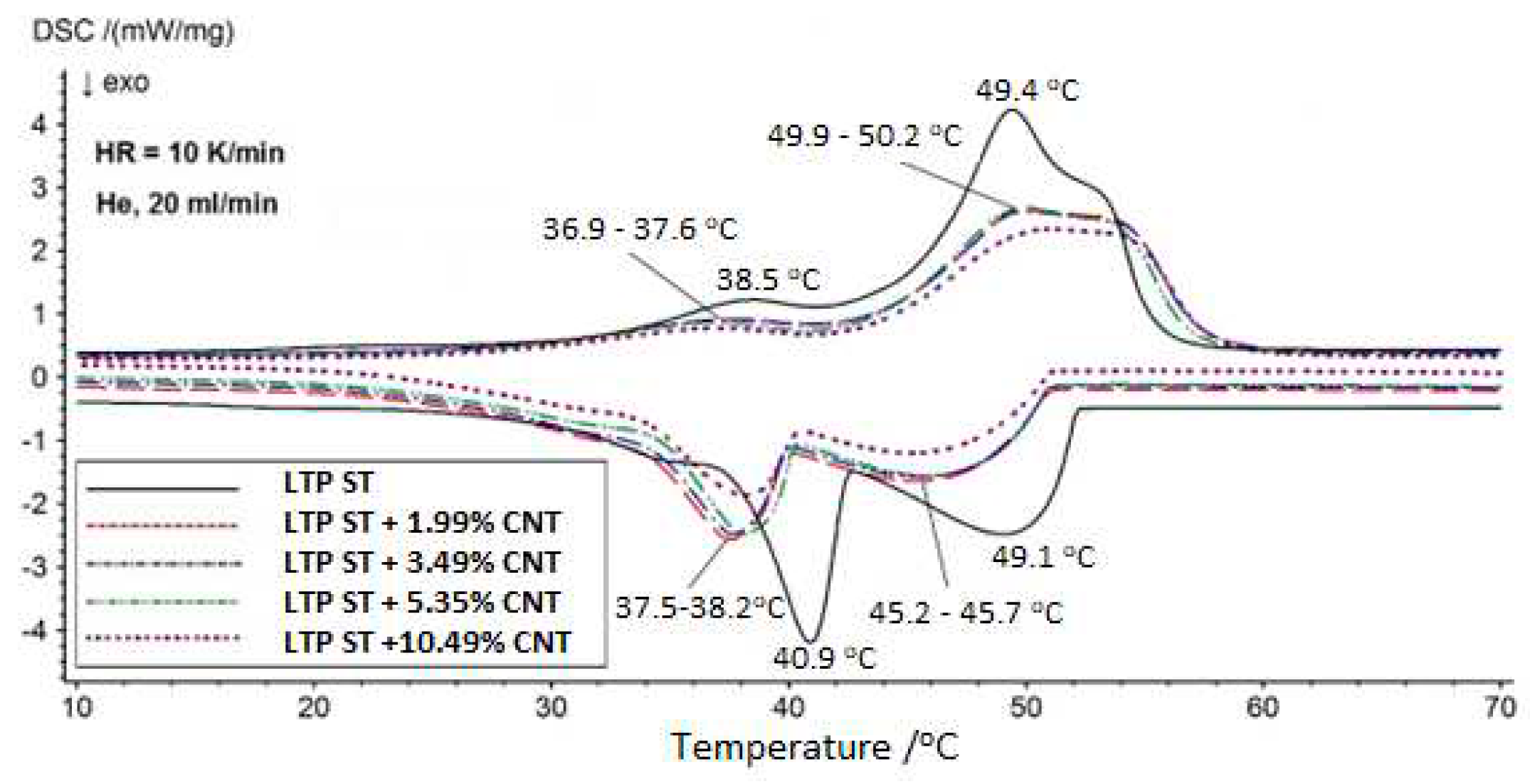

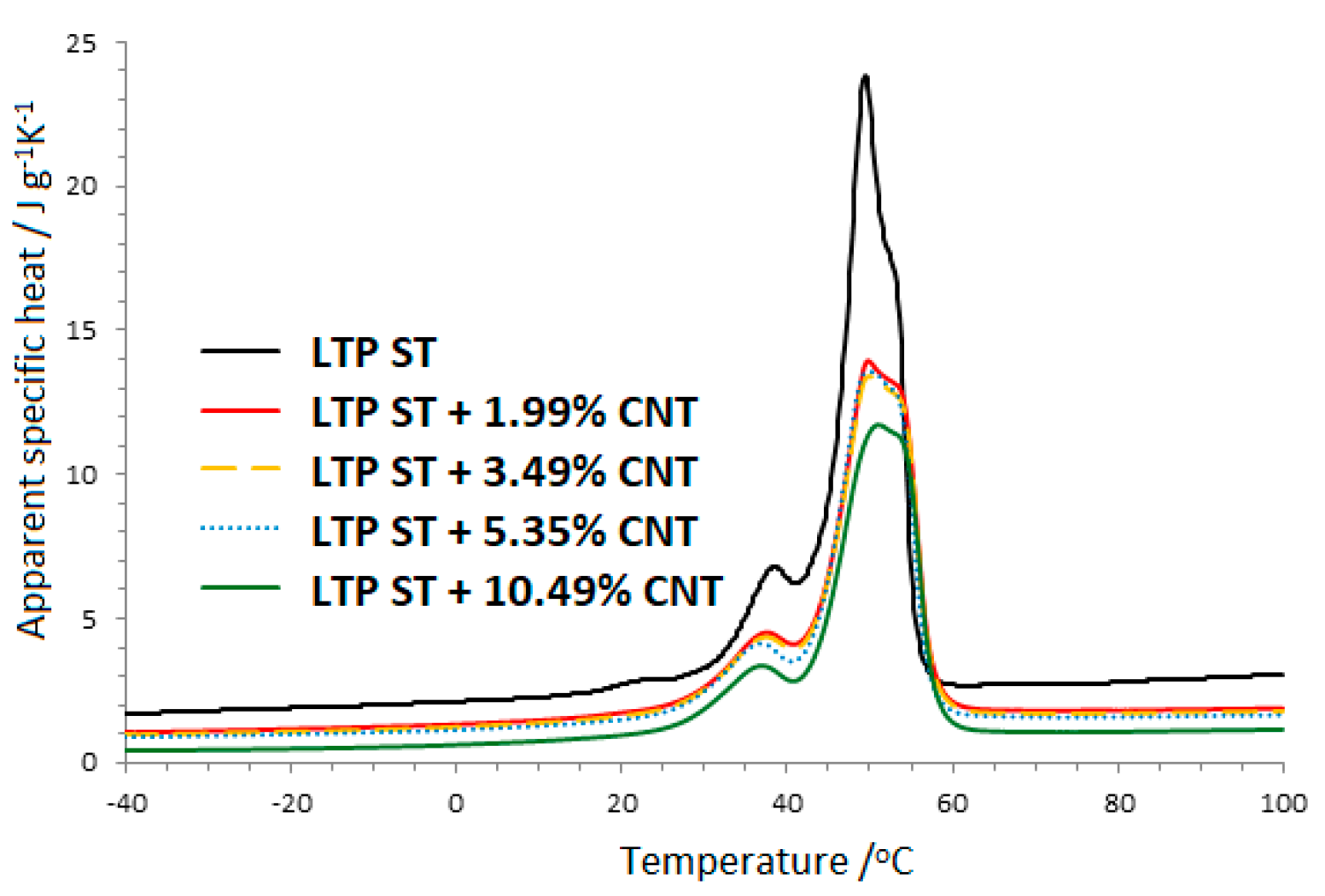

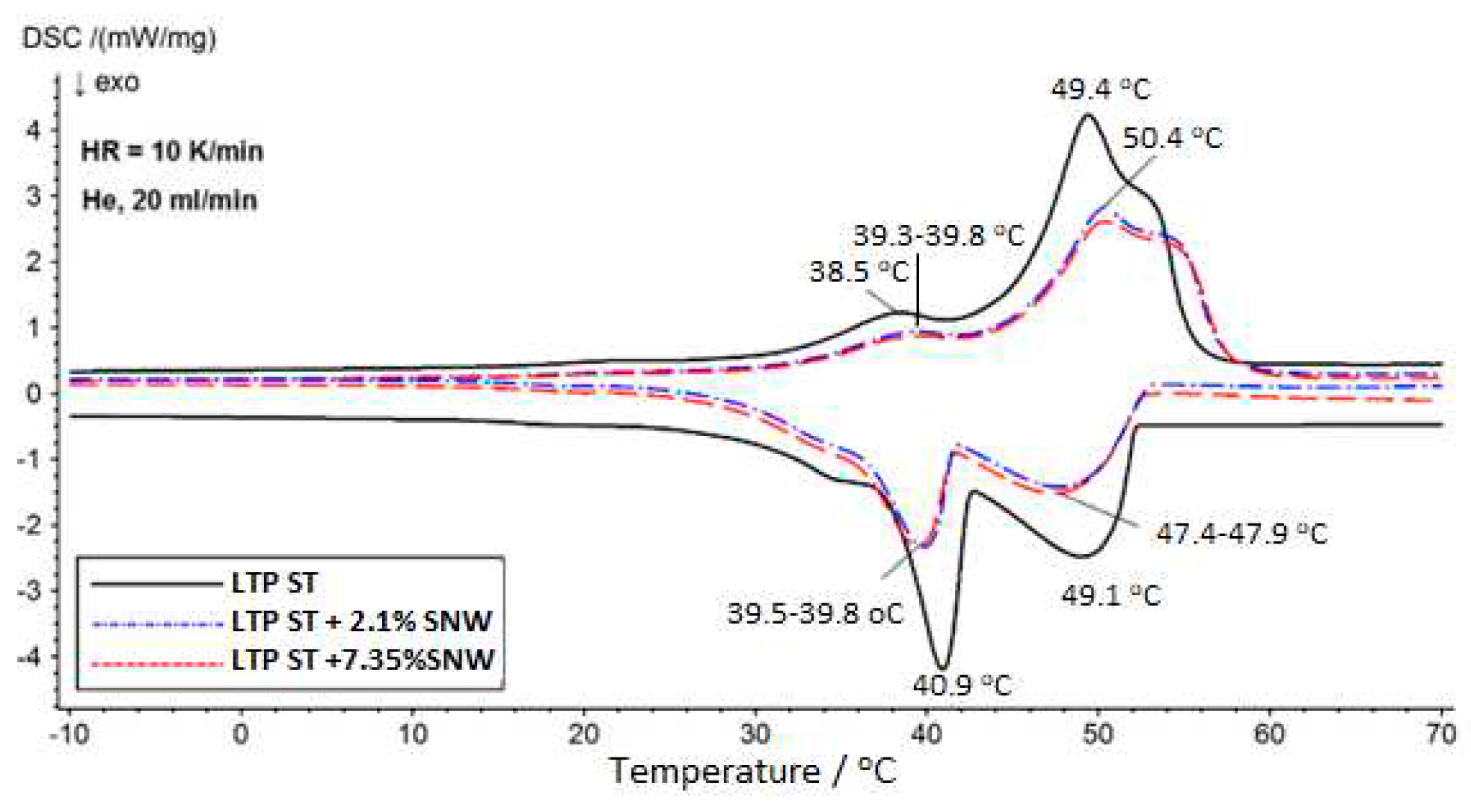

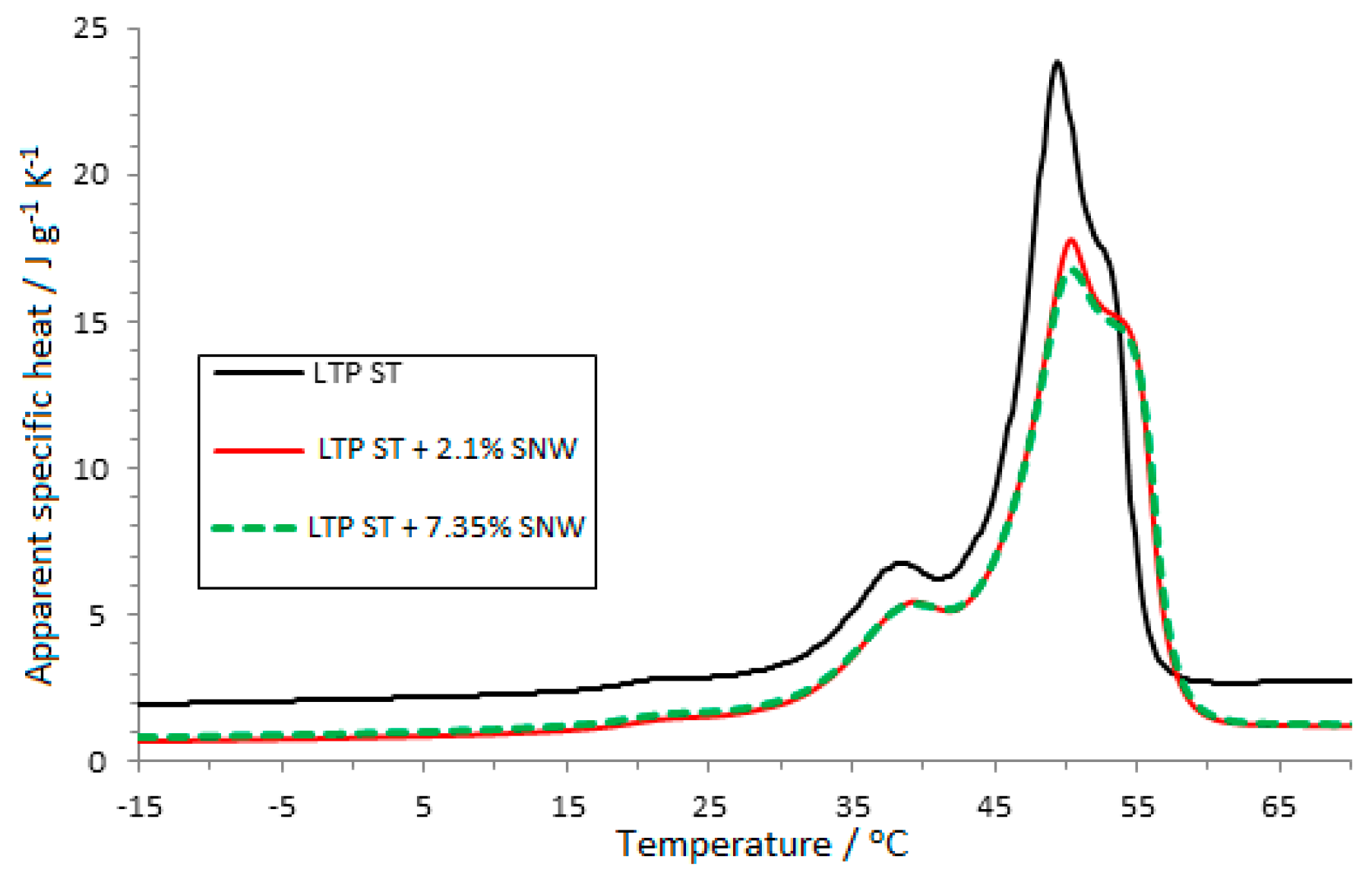

- The temperature course of the PCM material is characterized by a variable temperature rise rate in the range of 38÷48, which corresponds to the melting of LTP ST paraffin wax and is consistent with the DSC results.

5. Conclusions

- ✓

- Latent heat of fusion decreased by 25.1% for 10.49 wt% of MWNCT and 15.7% for 7.35 wt% of SNW compared to pure LTP ST paraffin (Table 3). The relative decrease in the latent heat of fusion in the case of MWCNT can be expressed by the correlation formula Δh/h = -1.179⋅wt% -13.128, R2=0.9644.

- ✓

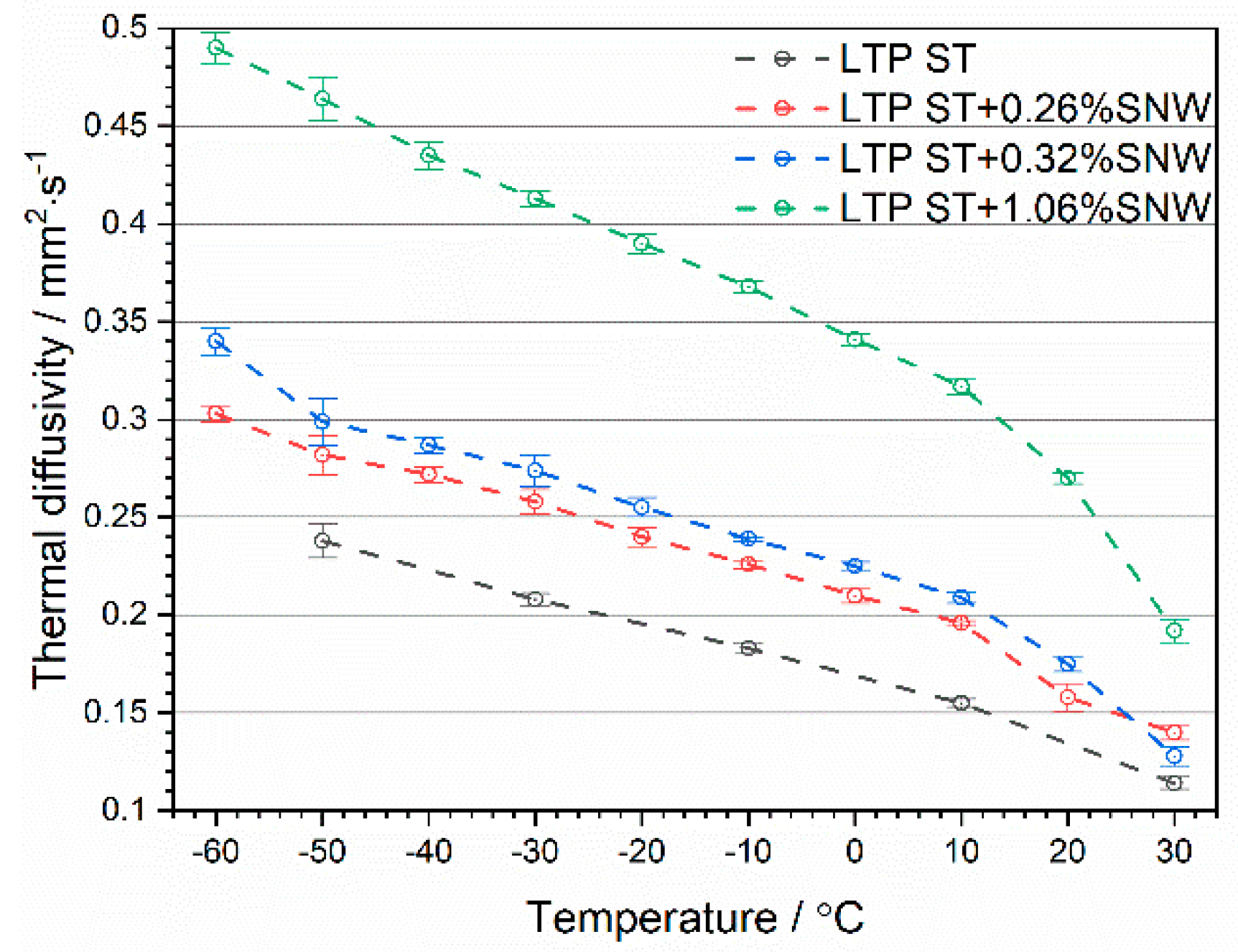

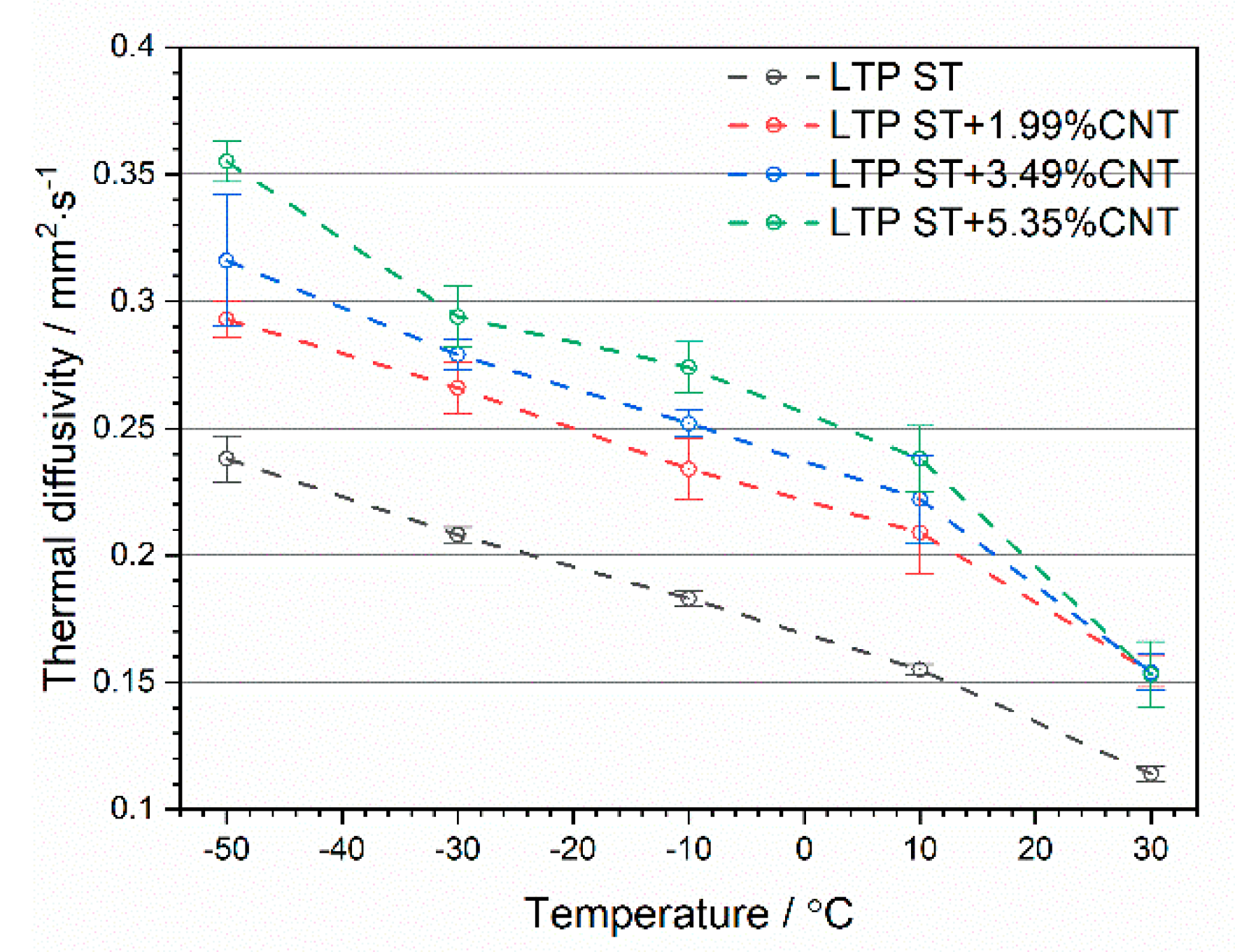

- The average increase in thermal diffusivity in the temperature range from -50 to 30 was 23.0%, 27.0%, 93.5% respectively for 0.26 wt%, 0.32 wt%, 1.06 wt% of SNW and 29.7%, 36.3%, 43.9% respectively for 1.99 wt%, 3.49 wt%, 5.35 wt% of MWCNT in relation to thermal diffusivity of LTP ST pure paraffin (Table 5).

- ✓

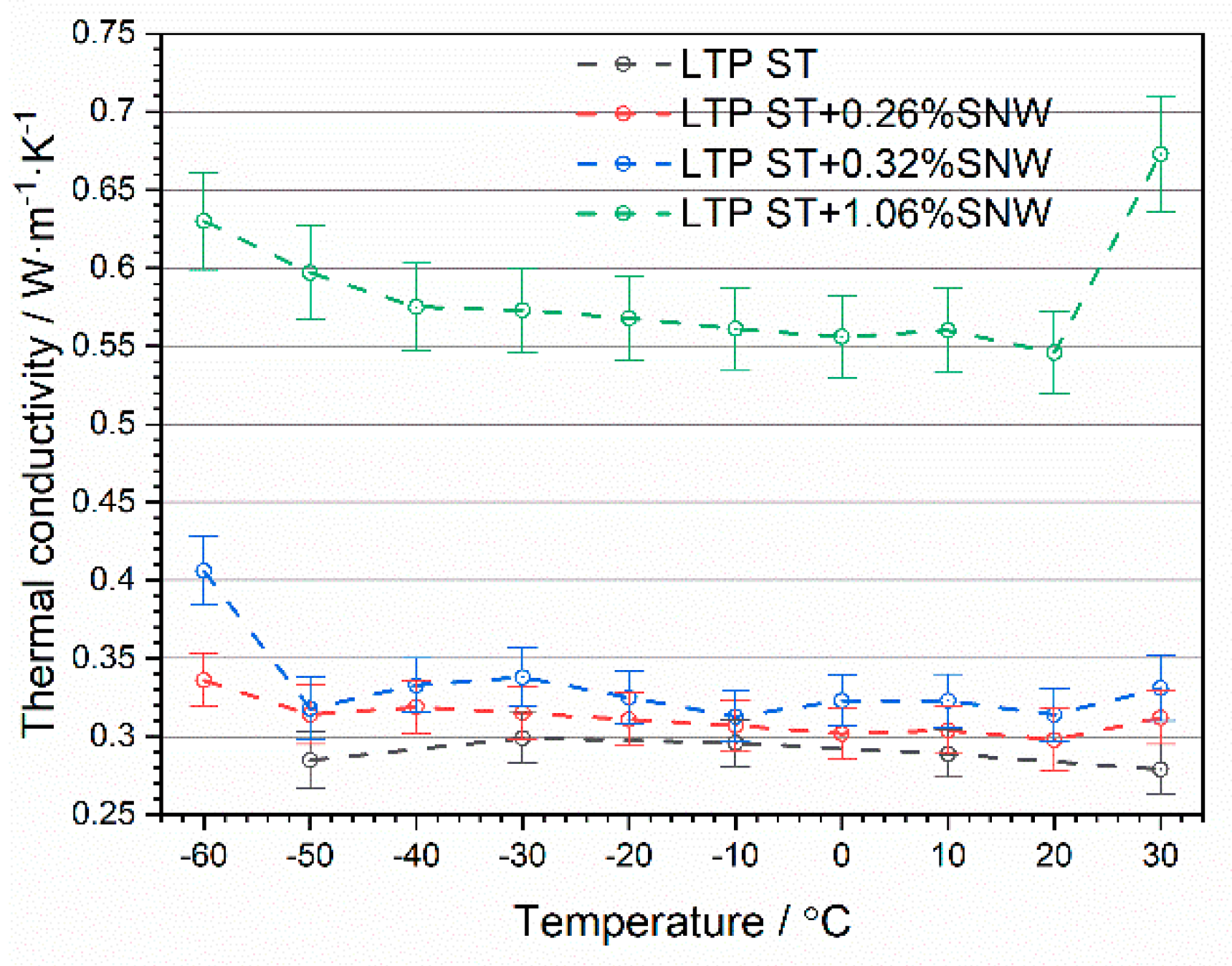

- The average increase in thermal conductivity in the temperature range from -50 to 30 was 7.2%, 12.4%, 105.1% for 0.26 wt%, 0.32 wt%, 1.06 wt% SNW and -6.6%, 3.3%, 7.1%, respectively for 1.99 wt%, 3.49 wt%, 5.35 wt% MWCNT relative to the thermal conductivity of pure LTP ST paraffin (Table 6).

- ✓

- The use of the heat sink in configuration C to cool the LED panel while it was in operation increased the time by 127% compared to configuration A, after which the LED panel temperature stabilized at 58 (Figure 14D).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Zbińkowski, P.; Zmywaczyk, J.; Koniorczyk, P. Experimental investigations of thermophysical properties of some paraffin waxes industrially manufactured in Poland. AIP Conference Proceedings 2017, 1866, 040044. [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar, S.; Sahu, G.; Muralidhar, K.; Gatapova, E.Y.; Kabov, O.A.; Hu, R.; Luo, X.; Zhao, L. Cooling of high-power LEDs by liquid sprays: Challenges and prospects. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 184, 115640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimputkar, S.; Speack, J.S.; DenBaars, S.P.; Nakamura, S. Prospects for LED lighting, Nat. Photon 2009, 3, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasance, C.J.M.; Poppe, A. (Eds.) Thermal management for LED Applications; Springer: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy, R.; Wang, X.Q.; Mujumdar, A.S. Transient cooling of electronics using phase change material (PCM)-based heat sinks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sökmen, K.F.; Yürüklü, E.; Yamankaradeniz, N. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 94, 534–542. [CrossRef]

- Weling, G.; Xuejiao, J.; Fei, Y.; Bifeng, C.; Wei, G.; Ying, L.; Weiwei, Y. Characteristics of high power LEDs at high and low temperature. J. Semicond. 2011, 32, 044007. [Google Scholar]

- Narendran, N.; Gu, Y. Life of LED-Based White Light Sources. IEEE/OSA Journal of Display Technology 2005, 1, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszek, J.; Domanski, R.; Rebow, M.; El-Sagier, F. Experimental study of solid-liquid phase change in a spiral thermal energy storage unit. Appl. Therm. Eng 1999, 19, 1253–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himran, S.; Suwono, A.; Mansoori, G.A. Characterization of Alkanes and Paraffin Waxes for Application as Phase Change Energy Storage Medium. Energy Sources 1994, 16, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, H.; Cabeza, L.F. Heat and Cold Storage with PCM. An up to date introduction into basics and applications (Springer, 2008), Heat and Mass Transfer Vol. 308.

- Farid, M.M.; Khudhair, A.M.; Razack, S.A.K.; Al-Hallaj, S. A review on phase change energy storage: materials and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 1597–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yasiri, Q.; Szabó, M. Paraffin as a Phase Change Material to Improve Building Performance: An Overview of Applications and Thermal Conductivity Enhancement Techniques. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2021, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Luo, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Molecular dynamics simulation on thermophysics of paraffin/EVA/ graphene nanocomposites as phase change materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 166, 114639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, N.; Fois, M.; Paksoy, H. The effects of various carbon derivative additives on the thermal properties of paraffin as a phase change material. Int. J. Energy Res. 2016, 40, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, X.; Tang, K. Experimental study of an enhanced phase change material of paraffin/ expanded graphite/nano-metal particles for a personal cooling system. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.; Khan, Z.A. Role of extended fins and graphene nano-platelets in coupled thermal enhancement of latent heat storage system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 224, 113349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinizadeh, S.F.; Tan, F.L.; Moosania, S.M. Experimental and numerical studies on performance of PCM-based heat sink with different configurations of internal fins. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 3827–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Research on passive cooling of electronic chips based on PCM: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, R.; Balaji, C. Thermal management of electronics using phase change material based pin fin heat sinks, 6th European Thermal Sciences Conference (Eurotherm 2012). Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2012, 395, 012134. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.M.; Ashraf, M.J.; Giovannelli, A.; Irfan, M.; Irshad, T.B.; Hamid, H.M.; Hassan, F.; Arshad, A. Thermal management of electronics: An experimental analysis of triangular, rectangular and circular pin-fin heat sinks for various PCMs. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 123, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Rahman, A.; Yadav, A.; Samykano, M.; Tyagi, V.V. Graphene-silver hybrid nanoparticle based organic phase change materials for enhancement thermal energy storage. sustainability 2022, 14, 13240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.smartnanotechnologies.com.pl (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Available online: https://3d-nano.com (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Alizadeh, H.; Pourpasha, H.; Heris, S.Z.; Estell´e, P. Experimental investigation on thermal performance of covalently functionalized hydroxylated and non-covalently functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes/transformer oil nanofluid. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2022, 31, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim S.H., Mulholland G.W., M.R. Zachariah G.W. Density measurement of size selected multiwalled carbon nanotubes by mobility-mass characterization. Carbon 2009, 47, 1297–1302. [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, S. Heat transfer; PWN; Warszawa, 1988; ISBN 83-01-07917-7; (In Polish).

- Panas, A.J.; Szczepaniak, R.; Stryczniewicz, W.; Omen, Ł. Thermophysical properties of temperature-sensitive paint. Materials 2021, 14, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.D. Pulse method of measuring thermal diffusivity at high temperatures. J. Appl. Phys. 1963, 34, 926–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panas, A.J.; Panas, J.J.; Polakowski, H.; Piątkowski, T. Badania zależności temperaturowych rozszerzalności cieplnej i ciepła właściwego stopu glinu PA-6, Biuletyn WAT Vol. LX, Nr 4, 2011 (in Polish).

- Zmywaczyk, J.; Zbińkowski, P.; Smogór, H.; Olejnik, A.; Koniorczyk, P. Cooling of high-power LED lamp using a commercial paraffin wax. Int. J. Thermophys 2017, 38, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaodva, S.; Baba, T.; Mori, T.; Huseynov, A.; Zeynalov, E. Thermal transport properties of MWCNT based natural Azerbaijani bentonite ceramic composities. Int. J. Thermophys 2023, 44, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample/ | LTP ST | 0.26% SNW | 0.32% SNW | 1.06% SNW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| density kg⋅m-3/ |

930.00(0.62%) | 954.76(0.11%) | 960.53(0.05%) | 1031.57(0.08%) |

| Sample/ | 2.1% SNW | 7.35% SNW | 1.99% CNT | 3.49% CNT | 5.35% CNT | 10.49% CNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| density kg⋅m-3/ |

1130.97(0.54%) | 1633.40(0.34%) | 946.12(1.09%) | 958.27(1.25%) | 973.34(1.50%) | 1015.00(2.16%) |

| Sample | LTP ST | 1.99% CNT | 3.49% CNT | 5.35% CNT | 10.49% CNT | 2.1% SNW | 7.35% SNW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / | 30.8 | 27.2 | 26.9 | 26.1 | 25.5 | 30.9 | 31.0 |

| / | 38.5 | 37.6 | 37.5 | 36.9 | 37.0 | 39.3 | 39.5 |

| / | 44.5 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 41.2 | 44.3 | 44.4 |

| / | 49.4 | 49.9 | 50.1 | 50.2 | 51.1 | 50.4 | 50.4 |

| / | 55.4 | 57.7 | 57.4 | 57.0 | 57.9 | 57.3 | 57.6 |

| / | 52.1 | 50.9 | 51.0 | 51.0 | 51.1 | 52.8 | 52.5 |

| / | 40.9/ 49.1 | 37.5/ 45.4 | 37.7/ 45.5 | 38.1/ 45.7 | 38.2/ 45.2 | 39.8/ 47.7 | 39.4/ 47.4 |

| / | 3.3 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| / | 227.2 | 192.8 | 189.2 | 180.2 | 170.2 | 195.9 | 191.5 |

| / | -230.0 | -193.2 | -187.8 | -182.0 | -168.0 | -192.1 | -192.5 |

| Sample | 1.99% CNT | 3.49% CNT | 5.35% CNT | 10.49% CNT | 2.1% SNW | 7.35% SNW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -60 | 0.303±0.004 | 0.340±0.007 | 0.490±0.008 | ||||

| -50 | 0.282±0.010 | 0.299±0.012 | 0.464±0.011 | 0.293±0.007 | 0.316±0.026 | 0.335±0.008 | 0.238±0.009 |

| -40 | 0.272±0.004 | 0.287±0.004 | 0.435±0.007 | ||||

| -30 | 0.258±0.006 | 0.274±0.008 | 0.413±0.004 | 0.266±0.010 | 0.279±0.006 | 0.294±0.012 | 0.208±0.003 |

| -20 | 0.240±0.005 | 0.255±0.005 | 0.390±0.005 | ||||

| -10 | 0.226±0.002 | 0.239±0.001 | 0.368±0.003 | 0.234±0.012 | 0.252±0.005 | 0.274±0.010 | 0.183±0.003 |

| 0 | 0.210±0.004 | 0.225±0.002 | 0.341±0.003 | ||||

| 10 | 0.196±0.001 | 0.209±0.003 | 0.317±0.004 | 0.209±0.016 | 0.222±0.017 | 0.238±0.013 | 0.155±0.002 |

| 20 | 0.158±0.007 | 0.175±0.004 | 0.270±0.003 | ||||

| 30 | 0.140±0.004 | 0.128±0.005 | 0.192±0.006 | 0.154±0.006 | 0.154±0.007 | 0.153±0.013 | 0.114±0.003 |

| -60 | 0.336±0.017 | 0.406±0.022 | 0.630±0.031 | |||||

| -50 | 0.314±0.019 | 0.318±0.020 | 0.597±0.030 | 0.249±0.014 | 0.307±0.029 | 0.311±0.017 | 0.285±0.018 | |

| -40 | 0.319±0.017 | 0.333±0.017 | 0.575±0.028 | |||||

| -30 | 0.315±0.017 | 0.338±0.019 | 0.573±0.027 | 0.261±0.016 | 0.304±0.027 | 0.327±0.021 | 0.299±0.016 | |

| -20 | 0.311±0.017 | 0.325±0.017 | 0.568±0.027 | |||||

| -10 | 0.307±0.016 | 0.313±0.016 | 0.561±0.026 | 0.283±0.020 | 0.302±0.016 | 0.347±0.022 | 0.296±0.015 | |

| 0 | 0.302±0.016 | 0.323±0.016 | 0.556±0.026 | |||||

| 10 | 0.304±0.015 | 0.326±0.017 | 0.560±0.027 | 0.282±0.025 | 0.298±0.027 | 0.303±0.022 | 0.289±0.015 | |

| 20 | 0.298±0.020 | 0.314±0.017 | 0.546±0.026 | |||||

| 30 | 0.312±0.017 | 0.331±0.021 | 0.673±0.037 | 0.276±0.018 | 0.285±0.019 | 0.265±0.026 | 0.279±0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).