Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

01 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

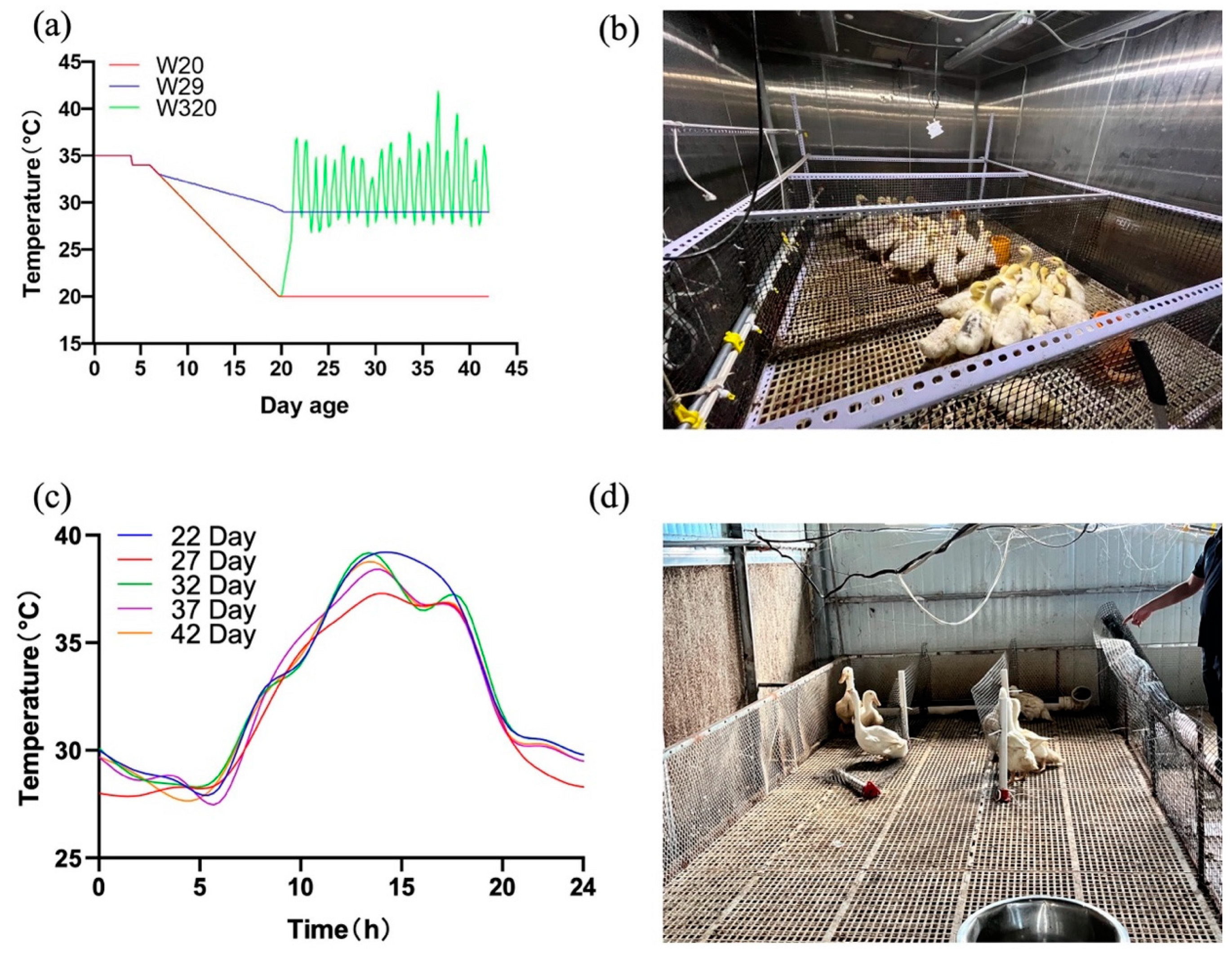

2.1. Animals, Animal Ethics, and Experimental Design

2.2. Measurements of Carcass Traits

2.3. Microscopic Structure of Lung

2.4. Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Pipeline

2.5. RNA Extraction, Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

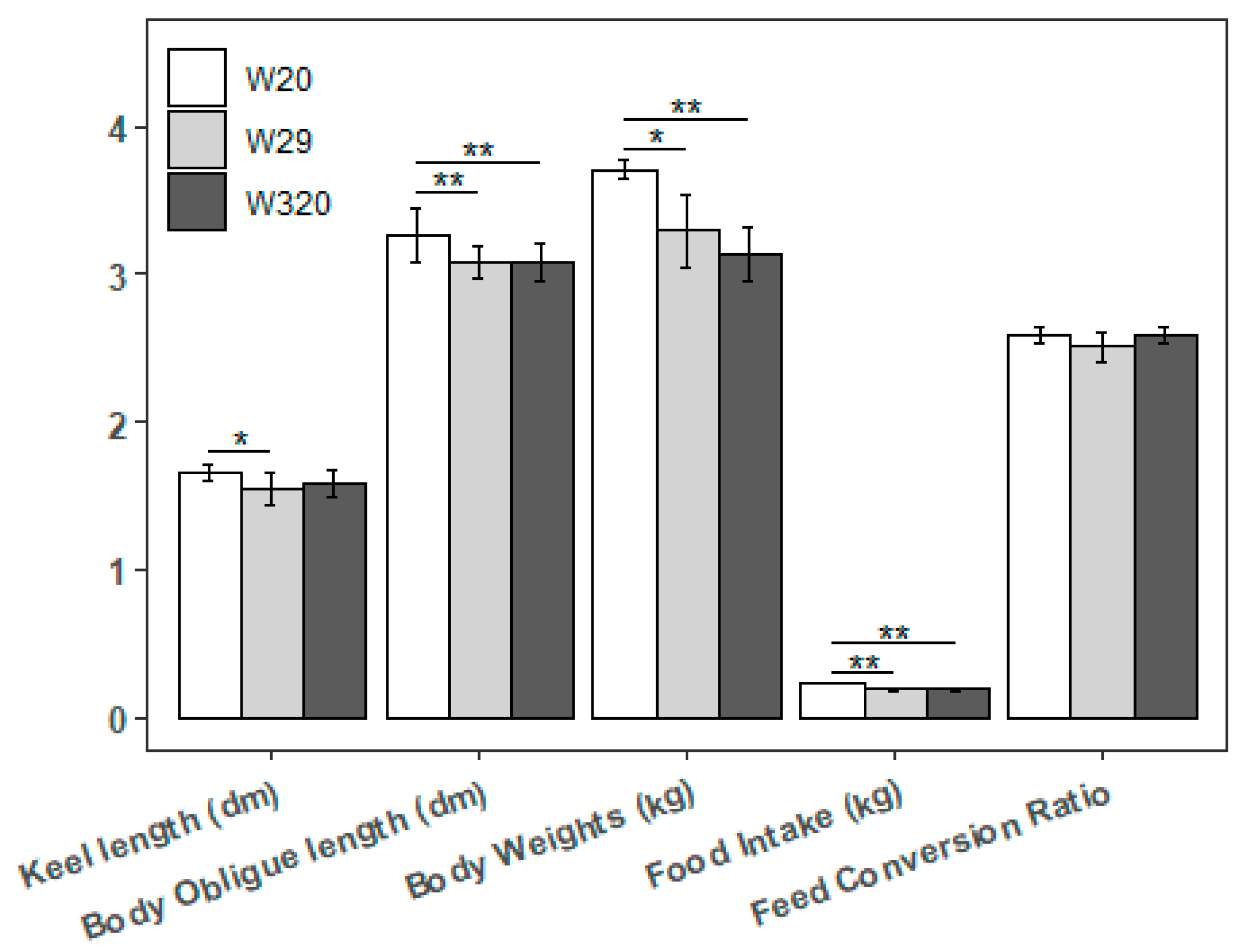

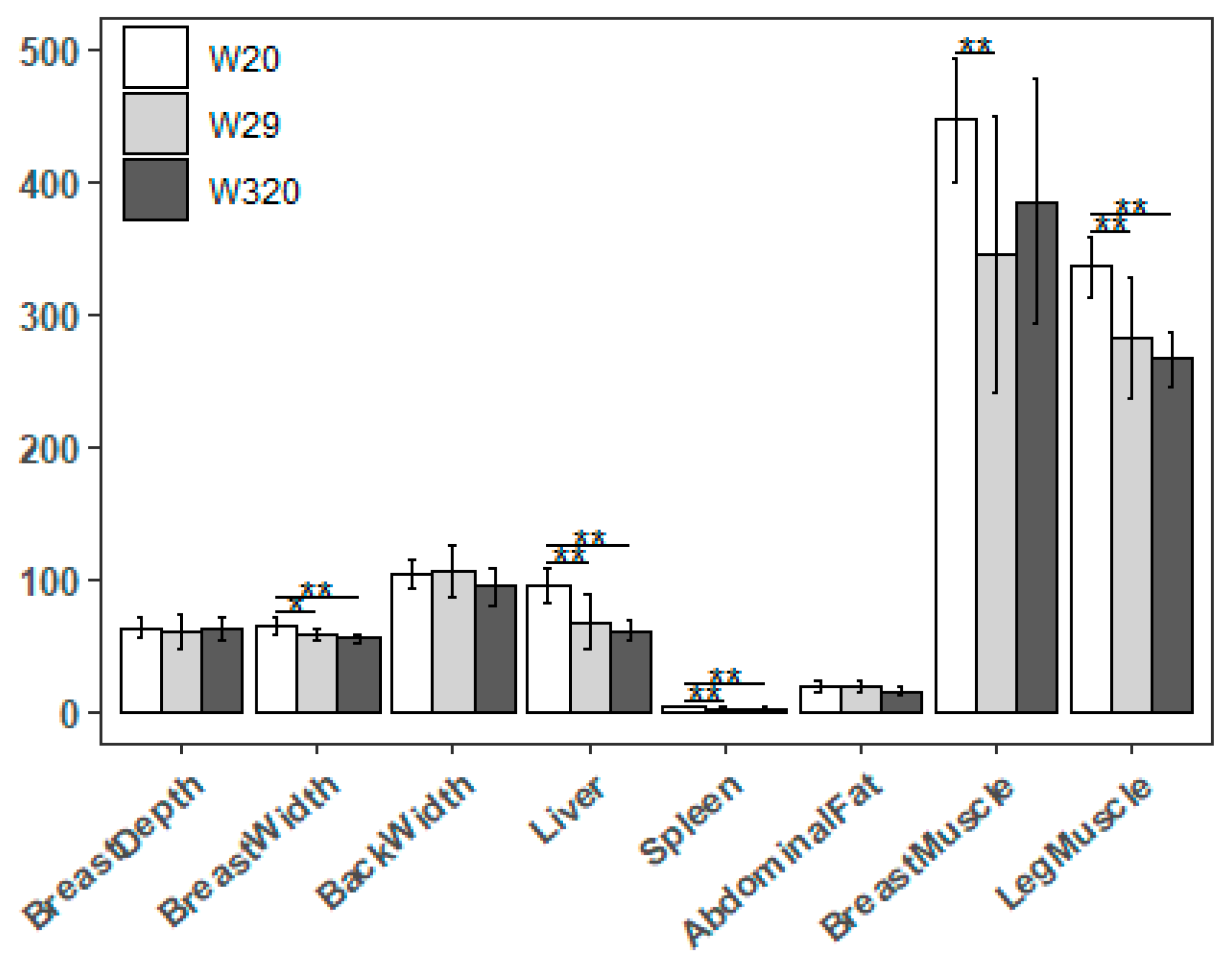

3.1. Growth Performance and Carcass Traits

3.2. Lung Appearance

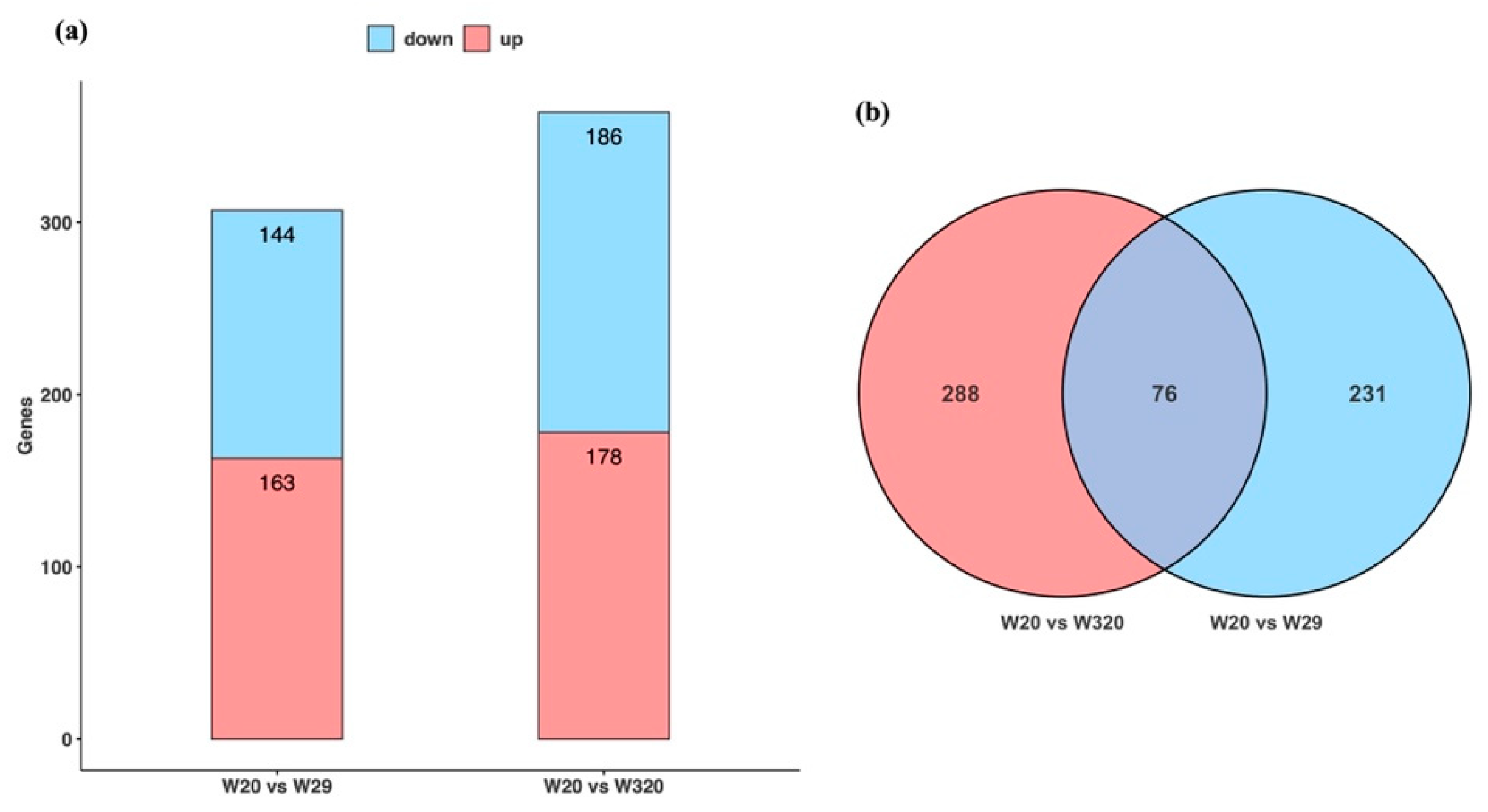

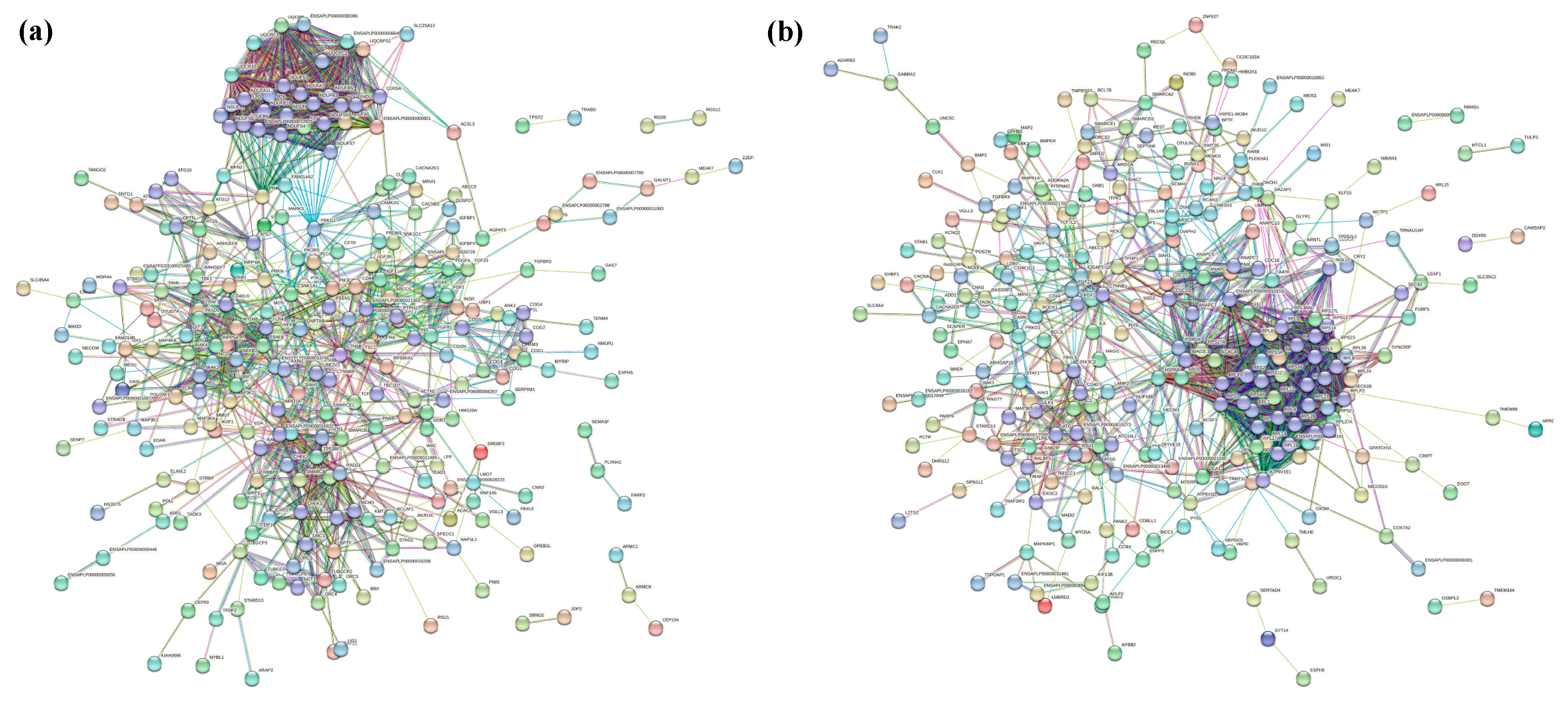

3.3. Bioinformatics Outcome

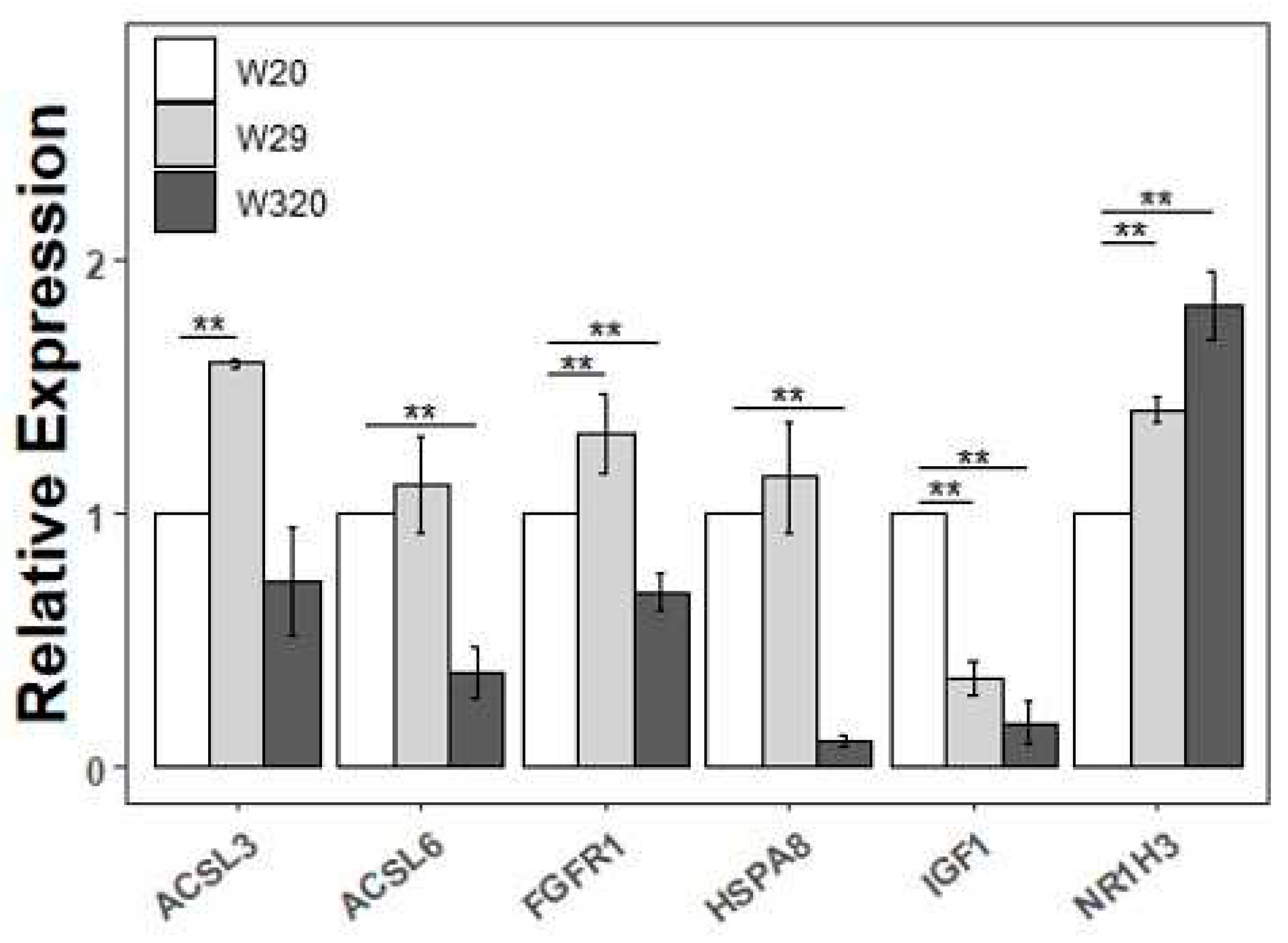

3.4. Real-Time Quantitative Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Validation

3.5. Potential Gene Markers for CHS

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brugaletta, G.; Teyssier, J.R.; Rochell, S.J.; Dridi, S.; Sirri, F. A review of heat stress in chickens. Part I: Insights into physiology and gut health. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 934381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaid, M.M.; Al-Garadi, M.A. Protein and Amino Acid Metabolism in Poultry during and after Heat Stress: A Review. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perini, F.; Cendron, F.; Rovelli, G.; Castellini, C.; Cassandro, M.; Lasagna, E. Emerging Genetic Tools to Investigate Molecular Pathways Related to Heat Stress in Chickens: A Review. Animals (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasti, S.; Sah, N.; Mishra, B. Impact of Heat Stress on Poultry Health and Performances, and Potential Mitigation Strategies. Animals (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, A.H.; Amoah, K.; Leng, Q.Y.; Zheng, J.H.; Zhang, W.L.; Zhang, L. Poultry Response to Heat Stress: Its Physiological, Metabolic, and Genetic Implications on Meat Production and Quality Including Strategies to Improve Broiler Production in a Warming World. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 699081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Gomez, J.S.; Uribe-Garcia, H.F.; Herrera-Sanchez, M.P.; Lozano-Villegas, K.J.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, R.; Rondon-Barragan, I.S. Heat stress on cattle embryo: gene regulation and adaptation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xie, T.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yang, H. Effects of Selenium as a Dietary Source on Performance, Inflammation, Cell Damage, and Reproduction of Livestock Induced by Heat Stress: A Review. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 820853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, A.M.; Johnson, T.G.; Metwally, K.; Farghly, M.; Mahrose, K.M. Environmental heat stress in rabbits: implications and ameliorations. Int J Biometeorol 2022, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohler, M.W.; Chowdhury, V.S.; Cline, M.A.; Gilbert, E.R. Heat Stress Responses in Birds: A Review of the Neural Components. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Yu, Y.H.; Hsiao, F.S.; Su, C.H.; Liu, H.C.; Tobin, I.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, Y.H. Influence of Heat Stress on Poultry Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Immune Function and Potential Mitigation by Probiotics. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.M.; Alqhtani, A.H.; Swelum, A.A.; Babalghith, A.O.; Melebary, S.J.; Soliman, S.M.; Khafaga, A.F.; Selim, S.; El-Saadony, M.T.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; et al. Heat stress in poultry with particular reference to the role of probiotics in its amelioration: An updated review. J Therm Biol 2022, 108, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ren, M.; Ren, K.; Jin, Y.; Yan, M. Heat stress impacts on broiler performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 6205–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas, P.A.; Chauhan, S.S.; Ha, M.; Fegan, N.; Dunshea, F.R.; Warner, R.D. Effects of heat stress on animal physiology, metabolism, and meat quality: A review. Meat Sci 2020, 162, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Oke, E.O.; Amevor, F.K.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Jiao, H.; Onagbesan, O.M.; Lin, H. Functional roles of taurine, L-theanine, L-citrulline, and betaine during heat stress in poultry. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.X.; Shen, Z.J.; Tang, J.; Huang, W.; Hou, S.S.; Xie, M. Effects of ambient temperature on growth performance and carcass traits of male growing White Pekin ducks. Br Poult Sci 2019, 60, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yong, Y.; Ju, X. Effect of heat stress on growth and production performance of livestock and poultry: Mechanism to prevention. J Therm Biol 2021, 99, 103019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostagno, M.H. Effects of heat stress on the gut health of poultry. J Anim Sci 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboli, G.; Huang, X.; Feng, X.; Ahn, D.U. How can heat stress affect chicken meat quality? - a review. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ratwan, P.; Dahiya, S.P.; Nehra, A.K. Climate change and heat stress: Impact on production, reproduction and growth performance of poultry and its mitigation using genetic strategies. J Therm Biol 2021, 97, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, G.D.; Sejian, V.; Lees, A.M.; Pragna, P.; Silpa, M.V.; Maloney, S.K. Heat stress and poultry production: impact and amelioration. Int J Biometeorol 2021, 65, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.E.; Shehata, A.M.; Khidr, R.E.; Paswan, V.K.; Ibrahim, N.S.; El-Ghoul, A.A.; Aldhumri, S.A.; Gabr, S.A.; Mesalam, N.M.; Elbaz, A.M.; et al. Nutritional manipulation to combat heat stress in poultry - A comprehensive review. J Therm Biol 2021, 98, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Ncho, C.M.; Choi, Y.H. Regulation of gene expression in chickens by heat stress. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, S.; Zaleta-Rivera, K. RNA: interactions drive functionalities. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 1413–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A. Heat stress management in poultry. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2021, 105, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Huang, X.B.; Chen, S.J.; Li, X.J.; Fu, X.L.; Xu, D.N.; Tian, Y.B.; Liu, W.J.; Huang, Y.M. The effect of heat stress on proliferation, synthesis of steroids, and gene expression of duck granulosa cells. Anim Sci J 2021, 92, e13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, T.; Li, J.J.; Wang, D.Q.; Li, G.Q.; Wang, G.L.; Lu, L.Z. Effects of heat stress on antioxidant defense system, inflammatory injury, and heat shock proteins of Muscovy and Pekin ducks: evidence for differential thermal sensitivities. Cell Stress Chaperones 2014, 19, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; Ruan, D.; Jiang, Z. Heat stress impairs the nutritional metabolism and reduces the productivity of egg-laying ducks. Anim Reprod Sci 2014, 145, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lim, K.S.; Byun, M.; Lee, K.T.; Yang, Y.R.; Park, M.; Lim, D.; Chai, H.H.; Bang, H.T.; Hwangbo, J.; et al. Identification of the acclimation genes in transcriptomic responses to heat stress of White Pekin duck. Cell Stress Chaperones 2017, 22, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Bao, E.; Yan, J.; Lei, L. Expression and localization of Hsps in the heart and blood vessel of heat-stressed broilers. Cell Stress Chaperones 2008, 13, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, S.C. Strategies to Improve Poultry Food Safety, a Landscape Review. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 2021, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; He, Y.; Zeng, T.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Xia, Q.; Zhou, C.; Pan, D.; Cao, J. Heat stress induces various oxidative damages to myofibrillar proteins in ducks. Food Chem 2022, 390, 133209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghly, M.F.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Swelum, A.A. Ameliorating deleterious effects of heat stress on growing Muscovy ducklings using feed withdrawal and cold water. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, C.; Xu, L.; Dai, X.; Feng, S.; Guo, C.; Rao, J.; et al. A new duck genome reveals conserved and convergently evolved chromosome architectures of birds and mammals. Gigascience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, D.V.; Zhang, L.; Pedersen, B.S.; Ramirez, F.; Warwick Vesztrocy, A.; Naldi, A.; Mungall, C.J.; Yunes, J.M.; Botvinnik, O.; Weigel, M.; et al. GOATOOLS: A Python library for Gene Ontology analyses. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Mao, X.; Huang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, S.; Kong, L.; Gao, G.; Li, C.Y.; Wei, L. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, W316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wu, H.H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko, M.T.; Lin, C.Y. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol 2014, 8 Suppl 4, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maere, S.; Heymans, K.; Kuiper, M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3448–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, R.C.; Ellstrom, P.; Howe, K.; Uliano-Silva, M.; Kuo, R.I.; Miedzinska, K.; Warr, A.; Fedrigo, O.; Haase, B.; Mountcastle, J.; et al. A high-quality genome and comparison of short- versus long-read transcriptome of the palaearctic duck Aythya fuligula (tufted duck). Gigascience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, R.; Wick, M.; Lilburn, M.S. Effect of embryonic thermal manipulation on heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) expression and subsequent immune response to post-hatch lipopolysaccharide challenge in Pekin ducklings. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, R.; Wick, M.; Lilburn, M.S. Effect of embryonic thermal manipulation on heat shock protein 70 expression and immune system development in Pekin duck embryos. Poult Sci 2018, 97, 4200–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Qin, T.Y.; Li, Q.S.; Li, X.X.; Qi, Z.L. A comparison of two sources of methionine supplemented at different levels on heat shock protein 70 expression and oxidative stress product of Peking ducks subjected to heat stress. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2018, 102, e147–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ou, K.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Evolution, dynamic expression changes and regulatory characteristics of gene families involved in the glycerophosphate pathway of triglyceride synthesis in chicken (Gallus gallus). Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ito, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Yamamoto, K.; Iwata, H. Effects on the hepatic transcriptome of chicken embryos in ovo exposed to phenobarbital. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 160, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Bezerra, M.; Cohen, D.E. Triglyceride Metabolism in the Liver. Compr Physiol 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, K.; Pan, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, D. Nano-selenium alleviating the lipid metabolism disorder of LMH cells induced by potassium dichromate via down-regulating ACACA and FASN. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28, 69426–69435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, K.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Kang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, H. Evolution, expression profile, and regulatory characteristics of ACSL gene family in chicken (Gallus gallus). Gene 2021, 764, 145094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desert, C.; Duclos, M.J.; Blavy, P.; Lecerf, F.; Moreews, F.; Klopp, C.; Aubry, M.; Herault, F.; Le Roy, P.; Berri, C.; et al. Transcriptome profiling of the feeding-to-fasting transition in chicken liver. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.K.; Kumar, J.; Rani, S.; Kumar, V. Annual life history-dependent gene expression in the hypothalamus and liver of a migratory songbird: insights into the molecular regulation of seasonal metabolism. J Biol Rhythms 2014, 29, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebratie, W.; Reyer, H.; Wimmers, K.; Bovenhuis, H.; Jensen, J. Genome wide association study of body weight and feed efficiency traits in a commercial broiler chicken population, a re-visitation. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.L.; DiMario, J.X. Bimodal, reciprocal regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 promoter activity by BTEB1/KLF9 during myogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21, 2780–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsani, E.; Kranis, A.; Maniatis, G.; Hager-Theodorides, A.L.; Kominakis, A. Detection of loci exhibiting pleiotropic effects on body weight and egg number in female broilers. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwagbenga, E.M.; Tetel, V.; Schober, J.; Fraley, G.S. Chronic heat stress part 1: Decrease in egg quality, increase in cortisol levels in egg albumen, and reduction in fertility of breeder pekin ducks. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1019741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zheng, C.; Xia, W.; Ruan, D.; Wang, S.; Cui, Y.; Yu, D.; Wu, Q.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effects of constant or intermittent high temperature on egg production, feed intake, and hypothalamic expression of antioxidant and pro-oxidant enzymes genes in laying ducks. J Anim Sci 2018, 96, 5064–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Zeng, Y.B.; Liu, L.X.; Song, Q.L.; Zou, Z.H.; Wei, Q.P.; Song, W.J. Effects of dietary chromium propionate on laying performance, egg quality, serum biochemical parameters and antioxidant status of laying ducks under heat stress. Animal 2021, 15, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xia, C.; He, Y.; Pan, D.; Cao, J.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, X. Proteomic responses to oxidative damage in meat from ducks exposed to heat stress. Food Chem 2019, 295, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xia, C.; Xia, Q.; He, J.; Cao, J.; Pan, D.; Sun, Y. Volatile flavor changes responding to heat stress-induced lipid oxidation in duck meat. Anim Sci J 2020, 91, e13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farghly, M.F.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Swelum, A.A. Wet feed and cold water as heat stress modulators in growing Muscovy ducklings. Poult Sci 2018, 97, 1588–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, M.M.; Hendricks, G.L., 3rd; Kalama, M.A.; Gehad, A.E.; Abbas, A.O.; Patterson, P.H. Effect of heat stress on production parameters and immune responses of commercial laying hens. Poult Sci 2004, 83, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashizawa, Y.; Kubota, M.; Kadowaki, M.; Fujimura, S. Effect of dietary vitamin E on broiler meat qualities, color, water-holding capacity and shear force value, under heat stress conditions. Anim Sci J 2013, 84, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarian, A.; Michiels, J.; Degroote, J.; Majdeddin, M.; Golian, A.; De Smet, S. Association between heat stress and oxidative stress in poultry; mitochondrial dysfunction and dietary interventions with phytochemicals. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2016, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, P.; Braber, S.; Garssen, J.; Wichers, H.J.; Folkerts, G.; Fink-Gremmels, J.; Varasteh, S. Beyond Heat Stress: Intestinal Integrity Disruption and Mechanism-Based Intervention Strategies. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.H.; Kang, D.; Park, J.; Khan, M.; Shim, K. Chronic heat stress regulates the relation between heat shock protein and immunity in broiler small intestine. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jiao, H.; Song, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Lin, H. Heat stress impairs mitochondria functions and induces oxidative injury in broiler chickens. J Anim Sci 2021, 93, 2144–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteiro-Filho, W.M.; Gomes, A.V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Ribeiro, A.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Astolfi-Ferreira, C.S.; Ferreira, A.J.; Palermo-Neto, J. Heat stress impairs performance and induces intestinal inflammation in broiler chickens infected with Salmonella Enteritidis. Avian Pathol 2012, 41, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Roh, S.G.; Lee, H.G. Heat-Shock Proteins Gene Expression in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells as an Indicator of Heat Stress in Beef Calves. Animals (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseindoust, A.R.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Kwon, I.K.; Chae, B.J. Productive performance of weanling piglets was improved by administration of a mixture of bacteriophages, targeted to control Coliforms and Clostridium spp. shedding in a challenging environment. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2017, 101, e98–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Gu, X. Proteomic changes of the porcine small intestine in response to chronic heat stress. J Mol Endocrinol 2015, 55, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, G.P. Stress-induced gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction and its inflammatory effects. J Anim Sci 2009, 87, E101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Luo, P.; Chen, S.J.; Deng, Z.C.; Fu, X.L.; Xu, D.N.; Tian, Y.B.; Huang, Y.M.; Liu, W.J. Resveratrol sustains intestinal barrier integrity, improves antioxidant capacity, and alleviates inflammation in the jejunum of ducks exposed to acute heat stress. Poult Sci 2021, 100, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Cao, Y.; Gu, T.; Chen, L.; Tian, Y.; Li, G.; Shen, J.; Tao, Z.; Lu, L. Alpha-Enolase Protects Hepatocyte Against Heat Stress Through Focal Adhesion Kinase-Mediated Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway. Front Genet 2021, 12, 693780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Jiang, L.; Chen, G.; Feng, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, C.; Qu, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, B.; Xiao, X. Constitutive heat shock protein 70 interacts with alpha-enolase and protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress. Free Radic Res 2011, 45, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhai, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Xing, B.; Miao, R.; Li, T.; Hong, T.; Wei, L. Structure and expression identification of Cherry Valley duck IRF8. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Hong, T.; Zhang, T.; Xing, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Miao, R.; Li, T.; Wei, L. Identification and antiviral effect of Cherry Valley duck IRF4. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kang, D.R.; Shim, K.S. Proteomic changes in broiler liver by body weight differences under chronic heat stress. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo Ghanima, M.M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Othman, S.I.; Taha, A.E.; Allam, A.A.; Eid Abdel-Moneim, A.M. Impact of different rearing systems on growth, carcass traits, oxidative stress biomarkers, and humoral immunity of broilers exposed to heat stress. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farghly, M.F.A.; Mahrose, K.M.; Cooper, R.G.; Ullah, Z.; Rehman, Z.; Ding, C. Sustainable floor type for managing turkey production in a hot climate. Poult Sci 2018, 97, 3884–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibian, M.; Ghazi, S.; Moeini, M.M. Effects of Dietary Selenium and Vitamin E on Growth Performance, Meat Yield, and Selenium Content and Lipid Oxidation of Breast Meat of Broilers Reared Under Heat Stress. Biol Trace Elem Res 2016, 169, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.J.; Liu, N.; Wu, X.H.; Wang, G.Y.; Lin, L. Glutamine alleviates heat stress-induced impairment of intestinal morphology, intestinal inflammatory response, and barrier integrity in broilers. Poult Sci 2018, 97, 2675–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Noreldin, A.E. Managerial and Nutritional Trends to Mitigate Heat Stress Risks in Poultry Farms. In Sustainability of Agricultural Environment in Egypt: Part II; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; 2018; pp. 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kucuk, O.; Sahin, N.; Sahin, K. Supplemental Zinc and Vitamin A Can Alleviate Negative Effects of Heat Stress in Broiler Chickens. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 94, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Smith, M.O.; Onderci, M.; Sahin, N.; Gursu, M.F.; Kucuk, O. Supplementation of zinc from organic or inorganic source improves performance and antioxidant status of heat-distressed quail. Poult Sci 2005, 84, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Jha, R. Strategies to modulate the intestinal microbiota and their effects on nutrient utilization, performance, and health of poultry. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2019, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xiao, K.; Ke, Y.L.; Jiao, L.F.; Hu, C.H.; Diao, Q.Y.; Shi, B.; Zou, X.T. Effect of a probiotic mixture on intestinal microflora, morphology, and barrier integrity of broilers subjected to heat stress. Poult Sci 2014, 93, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudeau, D.; Collin, A.; Yahav, S.; de Basilio, V.; Gourdine, J.L.; Collier, R.J. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal 2012, 6, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duah, K.K.; Essuman, E.K.; Boadu, V.G.; Olympio, O.S.; Akwetey, W. Comparative study of indigenous chickens on the basis of their health and performance. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 2286–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.-h.; Xie, L.; Nie, Q.-h.; Zeng, H.; Peng, Z.-j.; Zhang, D.-x.; Zhang, X.-q. The Effects of Different Sex-Linked Dwarf Variations on Chinese Native Chickens. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2012, 11, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, R.; Cahaner, A. The effects of the naked neck (Na) and frizzle (F) genes on growth and meat yield of broilers and their interactions with ambient temperatures and potential growth rate. Poult Sci 1999, 78, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; He, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Tao, L.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Yang, F.; Li, N.; et al. A novel deletion in KRT75L4 mediates the frizzle trait in a Chinese indigenous chicken. Genet Sel Evol 2018, 50, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, V.S.; Han, G.; Eltahan, H.M.; Haraguchi, S.; Gilbert, E.R.; Cline, M.A.; Cockrem, J.F.; Bungo, T.; Furuse, M. Potential Role of Amino Acids in the Adaptation of Chicks and Market-Age Broilers to Heat Stress. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 610541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, R.M.; Hassan, F.U.; Farag, M.R.; Nasir, T.A.; Ragni, M.; Mahgoub, H.A.M.; Alagawany, M. Thermal stress and high stocking densities in poultry farms: Potential effects and mitigation strategies. J Therm Biol 2021, 99, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.M.; Galal, A.; Radwan, L.M.; Abou-Emera, O.K.; Al-Homidan, I.H. Using major genes to mitigate the deleterious effects of heat stress in poultry: an updated review. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Eltahir, E.A.B. North China Plain threatened by deadly heatwaves due to climate change and irrigation. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | GenBank Accesion NO. | Primer Sequences (5’-3’) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1 | XM_005022553 | F: TGGCCTGTGTTTGCTTACCTR: GCCTCTGTCTCCACATACGA | 106 |

| FGFR1 | MH359131 | F: TTTTCTCACGACCCTCTGCCR: CCTCAGTGTCGCTTCAGTCC | 86 |

| ACSL3 | XM_005026417 | F: ACACTACCCCACTTTGCGATR: TCCACAAAGCAGGATGCGAA | 83 |

| ACSL6 | XM_038186369 | F: AAGAGCCATTGCACAAACGGR:TTGGTTGCAGAATGAACGCC | 118 |

| HSPA8 | XM_027444224.2 | F: AAGATGTCGAAGGGACCAGCR: CTGTGTCTGTGAAGGCGACA | 145 |

| NR1H3 | NM_001310423 | F: ACGCCCCAAATGAGTAGCATR: AAGAGGTGTATGTGCGTGGG | 74 |

| GAPDH | XM_038180584 | F: GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCAR: TCCTTGGATGCCATGTGGAC | 165 |

| Samples | Total clean reads | Total clean bases | unique match | multi-position match | Total mapped reads | Total unmapped reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W20 sample 1 | 140085820 (100.00%) | 17575757205 (100.00%) | 104694517 (74.47%) | 24316000 (17.36%) | 129010517 (92.09%) | 11075303 (7.91%) |

| W20 sample 2 | 152129548 (100.00%) | 19161362732 (100.00%) | 116442590 (76.54%) | 24961089 (16.41%) | 141403679 (92.95%) | 10725869 (7.05%) |

| W20 sample 3 | 141677462 (100.00%) | 18577850816 (100.00%) | 113895963 (80.39%) | 16964272 (11.97%) | 130860235 (92.36%) | 10817227 (7.64%) |

| W29 sample 1 | 132793402 (100.00%) | 17260232547 (100.00%) | 104917382 (79.01%) | 17256557 (13.00%) | 122173939 (92.00%) | 10619463 (8.00%) |

| W29 sample 2 | 140933246 (100.00%) | 17798316784 (100.00%) | 112350813 (79.72%) | 18298590 (12.98%) | 130649403 (92.70%) | 10283843 (7.30%) |

| W29 sample 3 | 118826918 (100.00%) | 15501757897 (100.00%) | 94655519 (79.66%) | 15227136 (12.81%) | 109882655 (92.47%) | 8944263 (7.53%) |

| W320 sample 1 | 128259234 (100.00%) | 16516406070 (100.00%) | 101193254 (78.90%) | 15625664 (12.18%) | 116818918 (91.08%) | 11440316 (8.92%) |

| W320 sample 2 | 118574410 (100.00%) | 15726318356 (100.00%) | 96473120 (81.36%) | 13380850 (11.28%) | 109853970 (92.65%) | 8720440 (7.35%) |

| W320 sample 3 | 122680820 (100.00%) | 16005030545 (100.00%) | 97552630 (79.52%) | 16017790 (13.06%) | 113570420 (92.57%) | 9110400 (7.43%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).