Submitted:

30 July 2023

Posted:

01 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- #1 ‘year[dp] NOT Review[pt]’;

- #2 ‘year[dp] AND Review[pt]’;

- #1 Abstracts from Research articles (excluding Reviews), published between 1989-2022 (n=680000)

- #2 Abstracts from Review articles, published between 1989-2022 (n=680000)

3. Results and Discussion

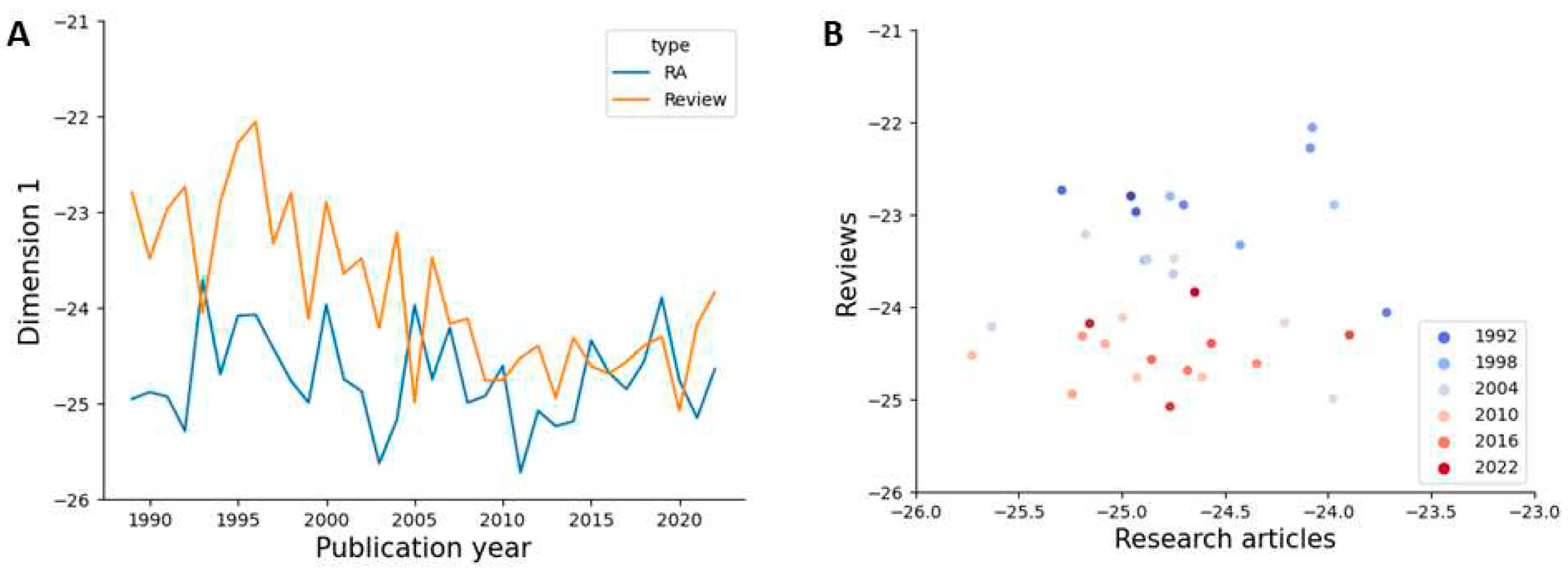

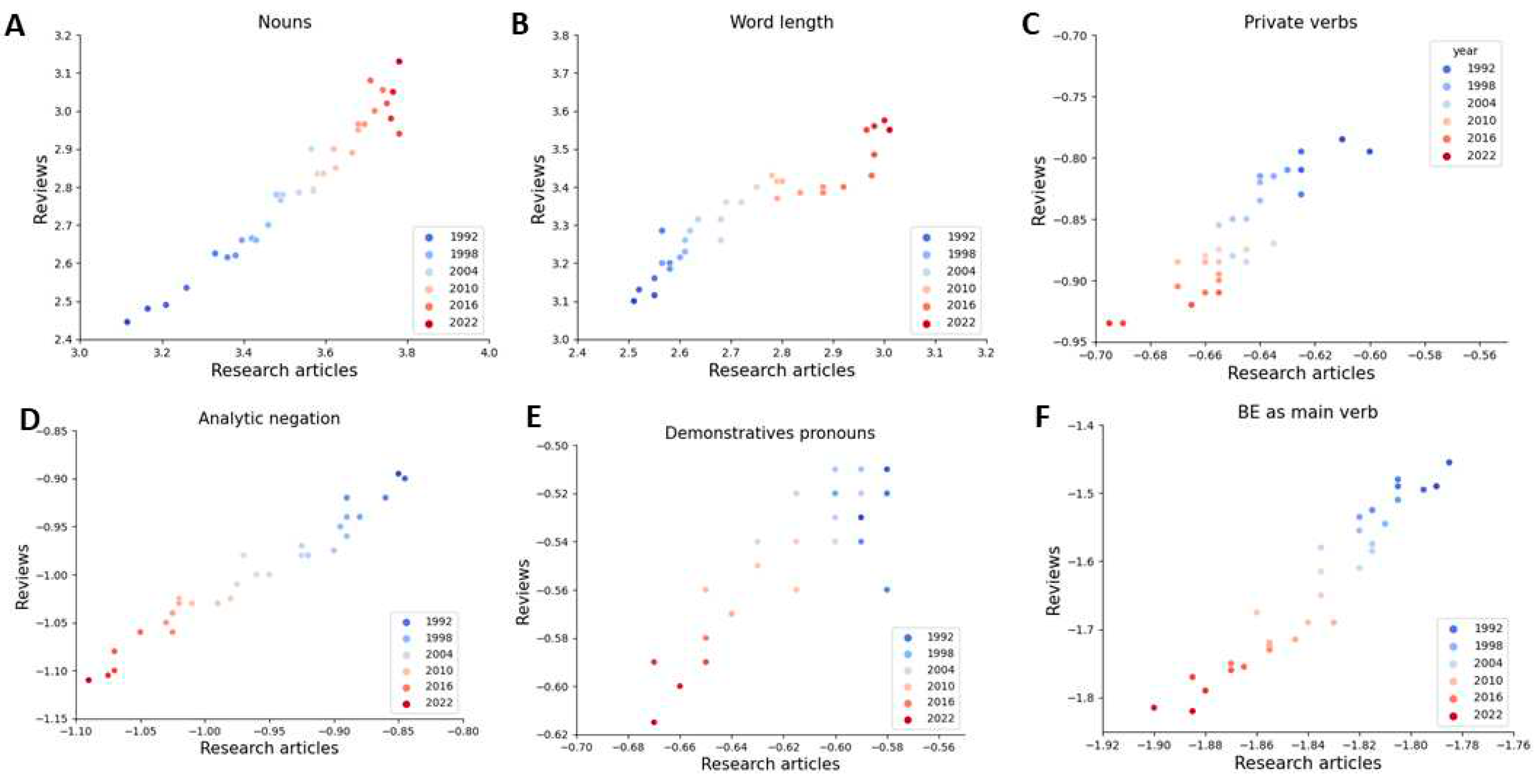

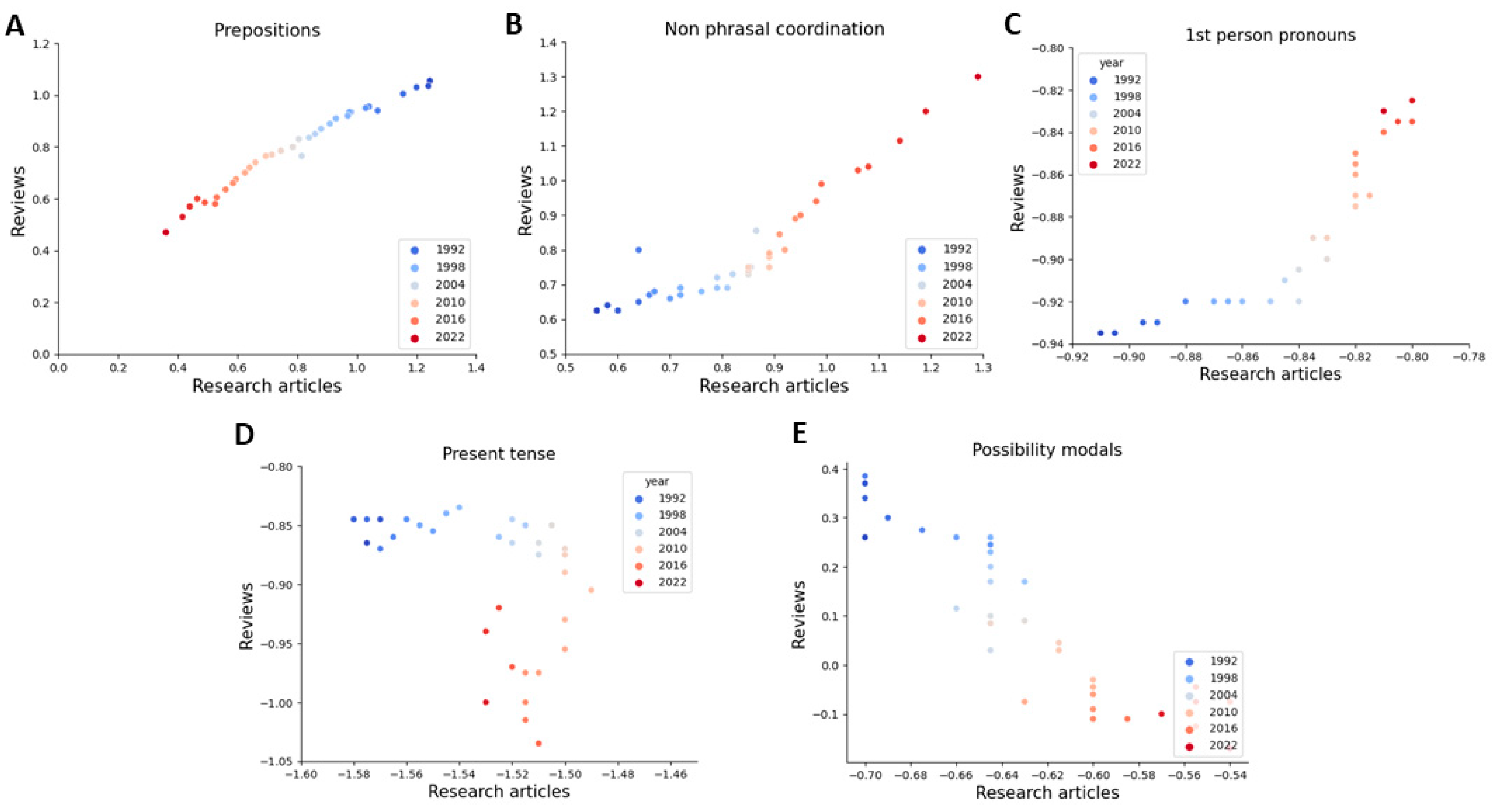

3.1. Dimension 1

It was my second clinical placement and I was working on a surgical ward when I was asked to accompany a patient to theatre.[30]

Primary care clinicians treat patients with cancer and cancer pain. It is essential that physicians know how to effectively manage pain including assessment and pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities.[34]

During 8 observation days (with time delay of 10-14 days between each observation day), all adult patients hospitalized at an internal medicine ward of 4 Belgian participating hospitals were screened for AB use. Patients receiving AB on the observation day were included in the study and screened for signs and symptoms of AAD using a period prevalence methodology.[35]

Administration of thioredoxin may have a good potential for anti-aging and anti-stress effects.[37]

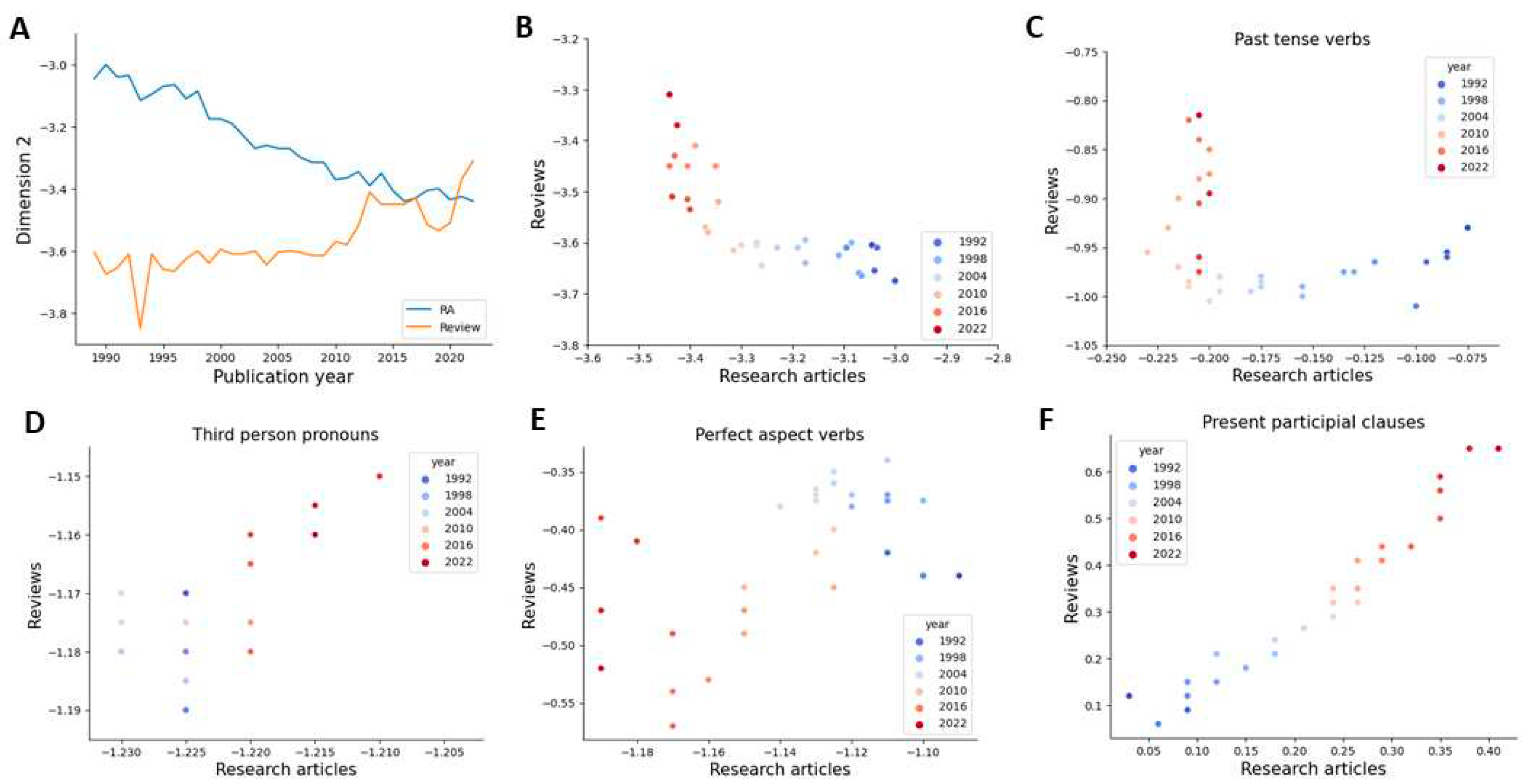

3.2. Dimension 2

We investigated expression of the five ssts in various adrenal tumors and in normal adrenal gland. Tissue was obtained from ten pheochromocytomas (PHEOs)….[39]

Several lines of evidence indicate that platelet-activating factor (PAF-acether) is implicated in hypersensitivity reactions. Indeed, PAF-acether reproduces the features of asthma in vivo and in vitro, since it induces bronchoconstriction, hypotension, and hemoconcentration and activates platelets and leukocytes.[40]

Mammalian neonates have been simultaneously described as having particularly poor memory, as evidenced by infantile amnesia, and as being particularly excellent learners.[41]

3.3. Dimension 3

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is characterized by high tumor invasiveness, distant metastasis, and insensitivity to traditional chemotherapeutic drugs….[50]

.. the specific mechanisms are blurry, especially the involved immunological pathways, and the roles of beneficial flora have usually been ignored.[50]

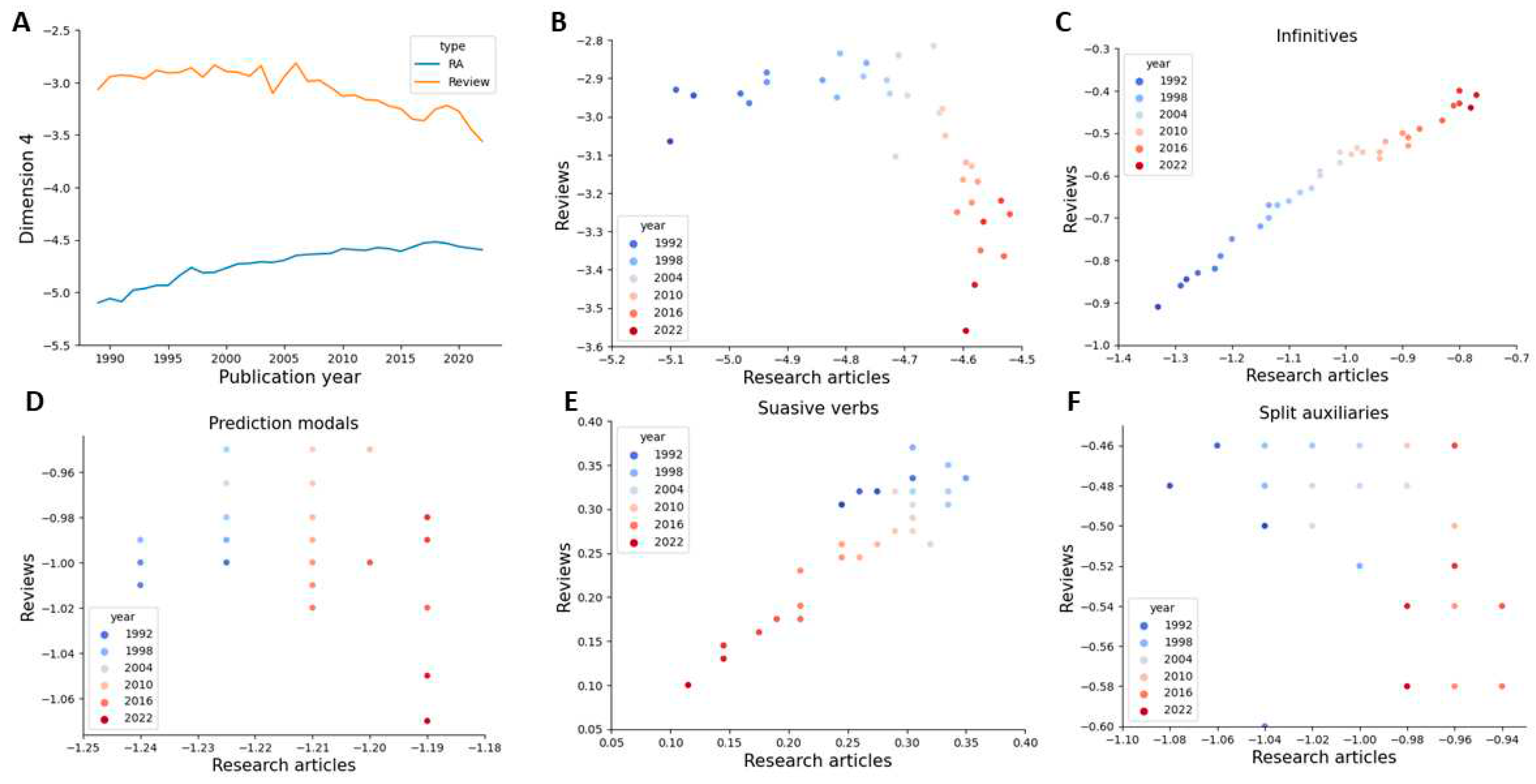

3.4. Dimension 4

Understanding the age-dependent neuromuscular mechanisms underlying force reductions … allows researchers to investigate new interventions to mitigate these reductions.[51]

…an ad hoc committee of the American Venous Forum, working with an international liaison committee, has recommended a number of practical changes.[52]

The data suggest that treatment of H. pylori infection should be considered in children with concomitant GERD.[53]

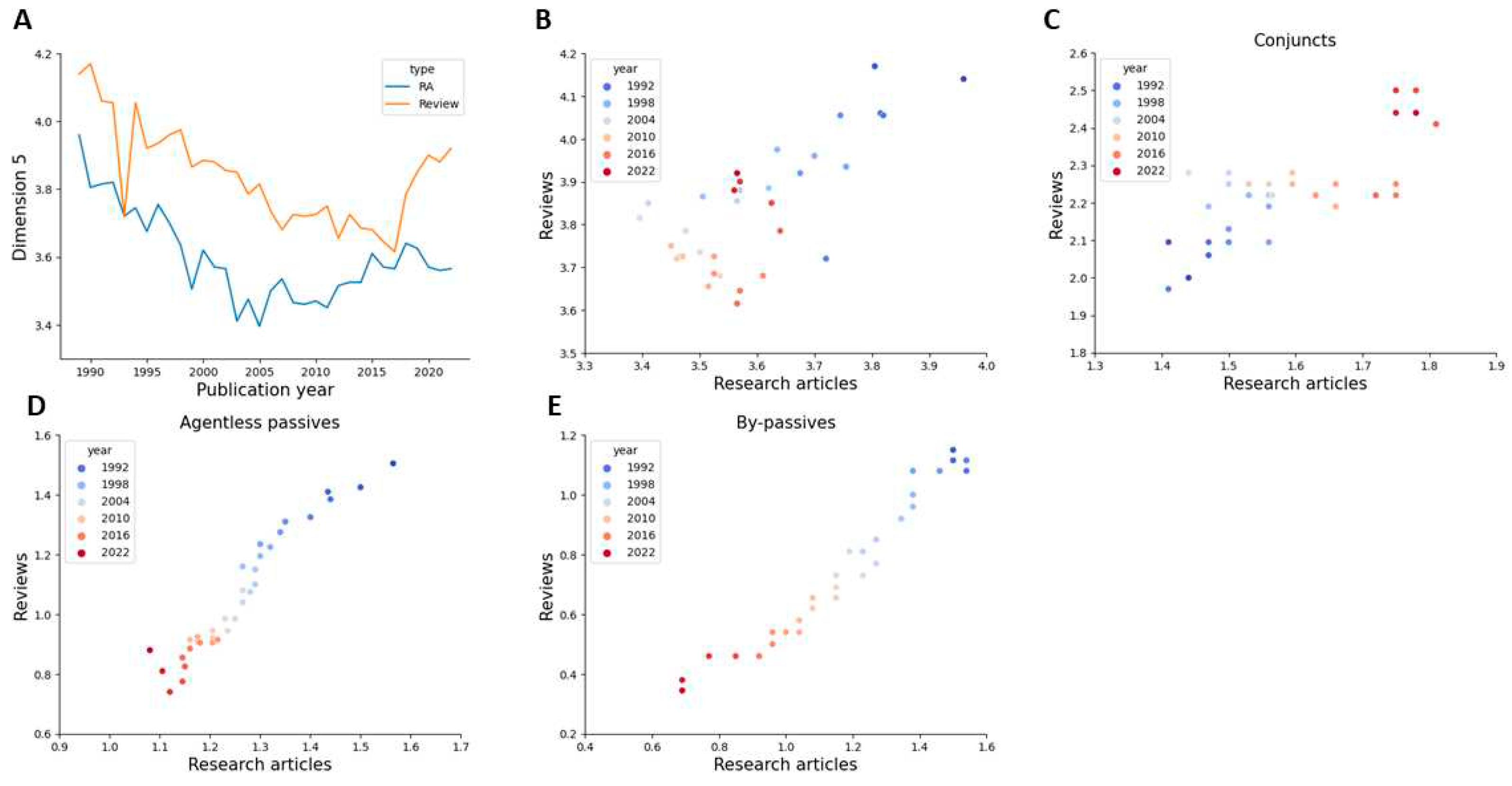

3.5. Dimension 5

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Dimension 1: Involved versus informational production Positive features (involved production) Private verbs that-deletions Contractions Present tense verbs do as pro-verb Analytic negation Demonstrative pronouns General emphatics First-person pronouns Pronoun it Causative subordination Discourse particles Indefinite pronouns General hedges Amplifiers Sentence relatives wh- questions Possibility modals Nonphrasal coordination wh- clauses Final prepositions Negative features (informational production) Nouns Word length Prepositions Type/token ration Attributive adjectives Dimension 2: Narrative versus nonnarrative discourse Positive features (narrative discourse) Past tense verbs Third-person pronouns Perfect aspect verbs Public verbs Synthetic negation Present participial clauses Dimension 3: Situation-dependent versus elaborated reference Positive features (situation-dependent reference) Time adverbials Place adverbials Adverbs Negative features (elaborated reference) wh- relative clauses in object positions Pied piping constructions wh- relative clauses in subject positions Phrasal coordination Nominalizations Dimension 4: Overt expression of persuasion Positive features (overt expression of persuasion) Infinitives Prediction modals Suasive verbs Conditional subordination Necessity modals Split auxiliaries (Possibility modals) Dimension 5: Nonimpersonal versus impersonal style Negative features (impersonal style) Conjuncts Agentless passives Past participial adverbial clauses By passives Past participial postnominal clauses Other adverbial subordinators

References

- Narin, F.; Pinski, G.; Gee, H.H. Structure of the Biomedical Literature. Journal of the American society for Information Science 1976, 27, 25–45.

- Cartabellotta, A.; Montalto, G.; Notarbartolo, A. Evidence-Based Medicine. How to Use Biomedical Literature to Solve Clinical Problems. Italian Group on Evidence-Based Medicine-GIMBE. Minerva Med 1998, 89, 105–115.

- Hrynaszkiewicz, I. The Need and Drive for Open Data in Biomedical Publishing. Serials 2011, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sanberg, P.R.; Gharib, M.; Harker, P.T.; Kaler, E.W.; Marchase, R.B.; Sands, T.D.; Arshadi, N.; Sarkar, S. Changing the Academic Culture: Valuing Patents and Commercialization toward Tenure and Career Advancement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 6542–6547. [CrossRef]

- Rice, D.B.; Raffoul, H.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Moher, D. Academic Criteria for Promotion and Tenure in Biomedical Sciences Faculties: Cross Sectional Analysis of International Sample of Universities. Bmj 2020, 369. [CrossRef]

- Landhuis, E. Scientific Literature: Information Overload. Nature 2016, 535, 457–458. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Verma, S. Predatory Journals: The Rise of Worthless Biomedical Science. J Postgrad Med 2018, 64, 226. [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q 2016, 94, 485–514.

- Pieper, D.; Antoine, S.-L.; Mathes, T.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.; Eikermann, M. Systematic Review Finds Overlapping Reviews Were Not Mentioned in Every Other Overview. J Clin Epidemiol 2014, 67, 368–375. [CrossRef]

- Biber, D. On the Complexity of Discourse Complexity: A Multidimensional Analysis. Discourse Process 1992, 15, 133–163. [CrossRef]

- Biber, D. Variation across Speech and Writing; Cambridge University Press, 1991; ISBN 0521425565.

- Stig, J.; Leech, G.N.; Goodluck, H. Manual of Information to Accompany the Lancaster-Oslo: Bergen Corpus of British English, for Use with Digital Computers. (No Title) 1978.

- Põldvere, N.; Johansson, V.; Paradis, C. On the London–Lund Corpus 2: Design, Challenges and Innovations. English Language & Linguistics 2021, 25, 459–483.

- Biber, D.; Conrad, S.; Reppen, R.; Byrd, P.; Helt, M. Speaking and Writing in the University: A Multidimensional Comparison. TESOL quarterly 2002, 36, 9–48. [CrossRef]

- Friginal, E.; Mustafa, S.S. A Comparison of US-Based and Iraqi English Research Article Abstracts Using Corpora. J Engl Acad Purp 2017, 25, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiao, R. A Multi-Dimensional Contrastive Study of English Abstracts by Native and Non-Native Writers. Corpora 2013, 8, 209–234. [CrossRef]

- Nini, A. The Multi-Dimensional Analysis Tagger. Multi-dimensional analysis: Research methods and current issues 2019, 67–94.

- Tausczik, Y.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods. J Lang Soc Psychol 2010, 29, 24–54. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, S.; Colangelo, M.T.; Mirandola, P.; Galli, C. The Evolution of Narrativity in Abstracts of the Biomedical Literature between 1989 and 2022. Publications 2023, 11, 26. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, S.; Colangelo, M.T.; Mirandola, P.; Galli, C. The Evolution of Narrativity in Abstracts of the Biomedical Literature between 1989 and 2022. Publications 2023, 11, 26. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A. Littler-Getter.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to Challenge the Spurious Hierarchy of Systematic over Narrative Reviews? Eur J Clin Invest 2018, 48, e12931. [CrossRef]

- Mckinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference; van der Walt, S., Millman, J., Eds.; 2010; pp. 51–56.

- Richardson, L. Beautiful Soup Documentation.

- Curtis, A.; Smith, T.; Ziganshin, B.; Elefteriades, J. The Mystery of the Z-Score. AORTA 2016, 04, 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput Sci Eng 2007, 9. [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J Open Source Softw 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kluyver, T.; Ragan-Kelley, B.; Pérez, F.; Granger, B.; Bussonnier, M.; Frederic, J.; Kelley, K.; Hamrick, J.; Grout, J.; Corlay, S.; et al. Jupyter Notebooks—a Publishing Format for Reproducible Computational Workflows. In Proceedings of the Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas - Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Electronic Publishing, ELPUB 2016; IOS Press BV, 2016; pp. 87–90.

- Liu, J.; Xiao, L. A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Conclusions in Research Articles: Variation across Disciplines. English for Specific Purposes 2022, 67, 46–61. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. My Cheerful Attitude Upset an Anxious Pre-Op Patient. Nursing Standard 2009, 24, 27–28. [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Authority and Invisibility. J Pragmat 2002, 34, 1091–1112. [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Options of Identity in Academic Writing. ELT Journal 2002, 56, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K.; Jiang, F. (Kevin) Is Academic Writing Becoming More Informal? English for Specific Purposes 2017, 45, 40–51. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.K.; Salunke, A.A.; Chawla, J.S.; Sharma, A.; Ratna, H.V.K.; Gautam, R.K. Bilateral Radial Head Fracture Secondary to Weighted Push-Up Exercise: Case Report and Review of Literature of a Rare Injury. Indian J Orthop 2021, 1–6.

- Elseviers, M.M.; Van Camp, Y.; Nayaert, S.; Duré, K.; Annemans, L.; Tanghe, A.; Vermeersch, S. Prevalence and Management of Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea in General Hospitals. BMC Infect Dis 2015, 15, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Carrió Pastor, M. Cross-Cultural Variation in the Use of Modal Verbs in Academic English. SKY Journal of Linguistics 2014, 27, 153–166.

- Nakamura, H. Experimental and Clinical Aspects of Oxidative Stress and Redox Regulation. Rinsho Byori 2003, 51, 109–114.

- Harris, E.E. Hypothesis and Perception: The Roots of Scientific Method; Routledge, 2014; ISBN 1317851609.

- Ueberberg, B.; Tourne, H.; Redman, A.; Walz, M.K.; Schmid, K.W.; Mann, K.; Petersenn, S. Differential Expression of the Human Somatostatin Receptor Subtypes Sst1 to Sst5 in Various Adrenal Tumors and Normal Adrenal Gland. Hormone and Metabolic Research 2005, 37, 722–728. [CrossRef]

- Pretolani, M.; Lellouch-Tubiana, A.; Lefort, J.; Bachelet, M.; Vargaftig, B.B. PAF-Acether and Experimental Anaphylaxis as a Model for Asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1989, 88, 149–153. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.A.; Sullivan, R.M. Neurobiology of Associative Learning in the Neonate: Early Olfactory Learning. Behav Neural Biol 1994, 61, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.L.; Blackburn, K.G.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Narrative Arc: Revealing Core Narrative Structures through Text Analysis. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Freytag, G. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama; Scott, Foresman, 1894;

- Corver, N.; van Riemsdijk, H. Semi-Lexical Categories: The Function of Content Words and the Content of Function Words; Walter de Gruyter, 2013; Vol. 59; ISBN 3110874008.

- Alexiadou, A. Nominalizations: A Probe into the Architecture of Grammar Part I: The Nominalization Puzzle. Lang Linguist Compass 2010, 4, 496–511. [CrossRef]

- Khamesian, M. On Nominalization, A Rhetorical Device in Academic Writing. Armenian Folia Anglistika 2015, 11, 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, A.M. Nominalization Development across an Undergraduate Academic Degree Program. J Pragmat 2010, 42, 1017–1036. [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Gray, B. Challenging Stereotypes about Academic Writing: Complexity, Elaboration, Explicitness. J Engl Acad Purp 2010, 9, 2–20. [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Gray, B. Nominalizing the Verb Phrase in Academic Science Writing. In The Register-Functional Approach to Grammatical Complexity; Routledge, 2021; pp. 176–198.

- Wei, X.; Mei, C.; Li, X.; Xie, Y. The Unique Microbiome and Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2021, 50, 119–129. [CrossRef]

- Orssatto, L.B. da R.; Wiest, M.J.; Diefenthaeler, F. Neural and Musculotendinous Mechanisms Underpinning Age-Related Force Reductions. Mech Ageing Dev 2018, 175, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Eklöf, B.; Rutherford, R.B.; Bergan, J.J.; Carpentier, P.H.; Gloviczki, P.; Kistner, R.L.; Meissner, M.H.; Moneta, G.L.; Myers, K.; Padberg, F.T.; et al. Revision of the CEAP Classification for Chronic Venous Disorders: Consensus Statement. J Vasc Surg 2004, 40, 1248–1252. [CrossRef]

- Pollet, S.; Gottrand, F.; Vincent, P.; Kalach, N.; Michaud, L.; Guimber, D.; Turck, D. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Neurologically Impaired Children: Inter-Relations and Therapeutic Implications. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004, 38. [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Feature |

|---|---|

| 1 | Involved vs. Informational discourse |

| 2 | Narrative vs. Non-Narrative Concerns |

| 3 | Context-Independent Discourse vs. Context Dependent Discourse |

| 4 | Overt Expression of Persuasion |

| 5 | Abstract and Non-Abstract Information |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).