1. Introduction

Over the last four decades of shifting to private-driven affordable housing, the housing deficit in Nigeria has been multiplying and the estimate is put at between 17 and 22 million units (World-Bank 2018: 3, Ajayi 2019: 232). This figure, when compared to other African countries (

Table 1) implies an urgent need to design better strategies for better housing delivery in Nigeria to stem the rising trend in housing deficit. Although these figures are just estimates, the reality of the housing situation in Nigeria is dire, especially in the cities where urbanisation and population growth (Adegun and Taiwo 2011: 457, Ajayi 2019: 232) have worsened the situation, with the low-income families being the most affected (World-Bank, 2018: 3, Ajayi, 2019: 223). Most importantly, is that the majority of the developments have failed to accommodate the nature of the housing situation; the cost of buying and renting a home has spiralled (Adegoke and Agbola 2020: 178), tenants in rental flats spend up to 60% of their average disposable income on housing (Adedeji, Deveci et al. 2023: 435). Consequently, vacant properties exist alongside homelessness, crowded living, slum, and squatter development (Aliyu and Amadu 2017: 150, Moore 2019: 205, Adegoke and Agbola 2020: 178) despite previous and ongoing efforts on affordable housing.

Poverty and unemployment rates are significantly high, the percentage living below the poverty line is now at 40.1% (NBS 2020: 5) and the unemployment and underemployment rates have continued to increase. By the fourth quarter of 2020 till now, 33.3% of the Nigerian labour force was unemployed and a further 22.8% was underemployed (NBS 2022). The prevailing low income arising from weak formal job creation, underemployment, low wage and insufficient skill development (Raschke 2016: 7) imposes an enormous strain on the capacity to fulfil their basic needs, including housing. Furthermore, access to mortgages is constrained, the mortgage to GDP ratio in Nigeria is only 0.5% as opposed to 31% in South Africa, 2% in Botswana, 2% in Ghana, 77% in the US, 50% in Hong Kong, 52% in Malaysia and an average of 50% in Europe (Ajayi, 2019: 224). Likewise, access to affordable homes is extremely low when compared to other African countries. Only 25% of the population in Nigeria can access affordable homes, as opposed to Indonesia (84%), Kenya (73%) and South Africa (56%) (Ajayi 2019: 223).

In the past, housing in Nigeria was marked by a series of failed public housing programmes, which did not address the housing needs of the low-income (Olayiwola, Adeleye et al. 2005: 2, Ajayi 2019: 224, Moore 2019: 206). Expectedly, this deficiency has always been supplanted by private efforts such that housing in Nigeria can be deemed as predominantly private-driven, accounting for about 90% of housing in Nigeria (Makinde 2014: 51). While the formal private sector, which comprises corporate institutions tend to supply housing for the high-income households and middle-income to some extent, the informal sector has always been left to cater for those households not accommodated in the formal sector (Adegun and Taiwo 2011: 458). However, despite being predominantly private-driven, housing has remained elusive to the low-income earners. Therefore, in recognition of the vast contributions made by the private sector to housing, the inefficiency of past public programmes, the various factors that presently challenge the government’s commitment to housing development (Elegbede, Olofa et al. 2015: 11, Ajayi 2019: 234), and the need to harness private resources more effectively, housing policies since 1991 have entrenched an enabled private-driven approach to facilitate housing provision for the low-income segment of the society.

The most recent National Housing Policy (NHP) of 2012 planned to tackle the housing deficit through the enabled private sector-driven approach (FGN 2012: 67). Although this policy direction, which has been held for four decades aimed to address the affordable housing problem in Nigeria, the problem persists because there is both low private investment in and low access to affordable housing (Makinde 2014: 62, World-Bank 2018: 3, Ajayi 2019: 230, Moore 2019: 213). Conteh, Earl et al. (2020: 1-3) linked low investment in affordable housing to its unprofitable nature, low returns, high risk and high illiquidity. In Nigeria, these factors manifest in the high transaction cost of land allocation, registration of titles, high interest rates, high cost of materials, and exchange rates (Makinde 2014: 62, Ajayi 2019: 234-235). However, a private developer seems to have defied these odds to develop housing that is adjudged the cheapest in Africa for three consecutive years (CAHF 2019: 5), challenging the long-held belief that private investment in affordable housing is impossible. Therefore, through an in-depth study of the Millard Fuller Foundation projects, this paper aims to fulfil these objectives:

To investigate the class of people targeted by the MFF housing projects;

To determine whether these projects have effectively responded to the housing needs of low-income earners;

To identify the strategies adopted in constructing and disposing of the MFF affordable housing in Luvu.

Addressing these objectives will highlight key considerations for designing appropriate enabling strategies for private-driven affordable housing in Nigeria.

2. Affordable housing and the Nigerian Context

The absence of a clear definition of affordable housing prevails in many countries; in the UK, it was used interchangeably with social housing to imply housing provided with public subsidies until a more specific definition distinguishes social housing as requiring subsidies to deliver housing at sub-market rates (Wilson and Barton 2022: 7). The same is evident in some countries in Europe where no formal definition of affordable housing exists, however, local interpretations and policy options imply that they are housing that costs less than what is provided by the market (Rosenfeld 2017: 4). Regardless of the interchangeable use of both terms, the definition of affordable housing in Wilson and Barton (2022: 7) shows that it encompasses both social housing and a wide mix of housing intended to satisfy the housing needs of a wide range of low to middle-income classes.

The use of a wide mix of houses in Wilson and Barton’s definition suggests a housing effort that offers a range of choices based on one’s income and therefore, establishes a relationship between housing and people, which is termed affordability (Stone 2006b: 153). Accordingly, the UN-Habitat (2011: 10) defined affordable housing as that, which is adequate in quality and location and does not cost so much that it prohibits its occupants from meeting other basic living costs or threatens their enjoyment of basic human rights. The fact that housing costs should not deny the fulfilment of other basic household needs has become an appropriate measure of affordable housing, and the implication is vividly captured in the Joint Centre for Housing Studies (JCHS 2020: 35-36). According to this survey, 71% of households earning less than $15,000 annually in America had a severe cost burden in 2019 leaving them with only $225 each month for all non-housing expenses. Over the years, identifying cost burdens using 30% of income has become the standard measure for determining housing affordability, however, it does not fully account for the cost of other basic needs or the sacrifices that households are likely to make (Airgood-Obrycki, Hermann et al. 2021: 1).

In contrast, the residual income approach assesses the residual income of a household, which is left after paying for housing (Stone, 2006: 163). It recognises that housing has distinct physical attributes, which when compared with other necessities makes the largest and least flexible claim on the after-tax income of households (Ibid). Hence, housing is unaffordable if the residual income cannot meet other non-housing needs like food, health care, transportation, child care and other necessary expenses at some basic level (Herbert and Mc Cue 2018). The JCHS referred to above clearly expressed this fact. Therefore, the residual income measure is particularly useful in identifying households that are struggling to get by after paying their housing cost. Unlike the 30% of income measure, the residual income approach is described as a sliding scale, which varies with both income and household type (Airgood-Obrycki, Hermann et al. 2021: 3). Hence, it is the difference between housing costs and income (Stone 2006b: 163). However, while this approach is considered to be better on account of its ability to define households that are shelter poor (that is, those who cannot fulfil other non-housing needs due to high housing costs), it still presents operational difficulties in determining the basic household expenses as these will vary with household circumstances. Hence, it will require an estimate of necessary non-housing expenses for a range of household configurations as well as an assumption of what a decent standard of living should be (ibid: 4).

The poor history of housing provision in Nigeria makes the definition of affordable housing somewhat difficult; however, various indicators and the policy direction have been used to provide a working definition in the context of this paper. First, the estimated housing deficit is concentrated on low-income families (Ajayi, 2019: 223; World-Bank, 2018: 3) who constitute a large proportion of the urban population (Raschke 2016: 6, World-Bank 2018: 3, CAHF 2020: 8). Secondly, there is a significant number of unoccupied houses in the city (Aliyu and Amadu, 2017: 150, Adegoke and Agbola, 2020: 178) and they are houses for sale and rental that urban dwellers cannot afford (Adegoke and Agbola, 2020: 178), forcing them into unhealthy living options (Olayiwola, Adeleye et al. 2005, Aliyu and Amadu 2017: 150, Moore 2019: 205, CAHF 2021: 194). Furthermore, the Policy direction is the provision of social housing for the no-income, low-income and low-middle-income (FGN, 2012: 66) for which strategies for enhancing access to housing include strengthening the mortgage system and the use of a contributory National Housing Fund (NHF). Accordingly, the policy categorises these groups (referred to as “the target groups” in this paper) as shown in

Table 2.

The direction of the policy implies a great need for affordable housing, for instance, if the NBS (2020: 5) and other estimates are used as a benchmark, it will be safe to assume that a conservative estimate of 50%

1 of the population is in need of affordable housing in the strictest sense. Furthermore, 70% to 80% of civil servants are on grade levels 1 to 10 (Chime 2016: 9), and they generally earn between

₦422, 566 and

₦1, 535, 417 annually (National Salaries, Incomes and Wages Commission (NSIWC 2019), which places them within the target groups. On account of their low income, they have low affordability for the NHF mortgages (see

Table 3), which creates a wide affordability gap when compared with the average cost of housing in Nigeria (see

Table 4 and

Table 5), Therefore, in view of these factors, and in the absence of a welfare system, one wonders how to enable private development of houses that can meet the need of the target groups while allowing them to fulfil other basic needs. Hence, affordable housing in this paper includes housing that is designed to meet the housing need of the target groups.

2.1. The Housing Market and Implications of Private sector driven Affordable Housing in Nigeria

The Nigeria’s housing market is influenced by some factors that affect the demand and supply of housing. The population of Nigeria is estimated at 212 million as of 2021 and more than half of this population lives in cities implying a huge need for housing (CAHF 2021: 193); furthermore, about 80% of the urban population lives in substandard conditions (World Bank, 2018: 3; Raschke, 2016: 6), while 58.8% of the urban population lives in slums (CAHF 2020: 8), which signifies poor access to housing and huge demand for affordable housing. Generally, poor access to housing is hinged on low disposable income, poor salary and high cost of living. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, over 40% of the population lives below the poverty line of NGN137, 430/annum (US$334) (NBS 2021: 5), hence, are unable to afford basic needs including housing. In some countries like the UK and USA, such people will generally be assisted with housing benefits and housing vouchers respectively to enable them to pay their rent (Wilson and Barton 2019: 31, Perkins 2022); however, such a system is absent in Nigeria, creating further demand challenges, which can affect private investment.

Both government and private efforts have failed to address the housing needs of the low-income (Adegun and Taiwo 2011: 458, Ibem 2011: 202, Makinde 2014: 51), and current housing efforts from both sectors are still lagging in that respect. The average price of houses from both sectors (

Table 4) shows that housing is unaffordable for a majority considering the prevailing low income. The backlog of supply arising from such practice over the years creates a huge gap in the affordable end of the market, which offers huge investment opportunities if appropriately harnessed and yet, private investors and even the government are unwilling to accept that serving the low-income market can be profitable (Raschke, 2016: 8). This is due to some operational challenges present in the market.

Table 4.

Average prices of houses by private developers and the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing.

Table 4.

Average prices of houses by private developers and the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing.

| Average house prices from the private sector |

|

National housing programme houses across Nigeria |

| Bedrooms |

Abuja |

Lagos |

Kaduna |

Flat in condominium |

| 2 |

|

26,670,000 |

16,912,494 |

1 bedroom |

2 bedrooms |

3 bedrooms |

| 3 |

51,740,000 |

|

29,637,327 |

7,222,404 |

9,148,378.4 |

13,241,074 |

| 4 |

84,330,000 |

62,740,000 |

35,796,239 |

Bungalow |

| 5 |

142,680,00 |

87,970,00 |

49,280,015 |

9,268,751 |

12,398,460.2 |

16,491,155.8 |

Access to land remains a central issue in housing provision since land is governed by land tenure systems (Lawal and Adekunle 2018: 2). This system operates within a regulatory framework, which is the Land Use Act of 1978 (LUA). This Act was originally intended to make land available and accessible for developmental purposes (Ghebru and Okumo 2016: 6) and vests all land to each state governor whose consent formalises land transaction and registration. Generally, this process is lengthy and costly and impacts negatively on construction-related inputs like materials and finance.

In terms of affordability, land price is volatile and varies greatly with its location and the availability of infrastructure (CAHF, 2021: 195); the infrastructure stock in Nigeria is 30%, which is below the World Bank benchmark of 70%. It reflects in insufficient road network linking commercial centres across the country (International Trade Administration (ITA 2021). Therefore, the cost of unserviced land without adequate title in suburban areas ranges from ₦926/m2 (US$ 2.3/m2) to ₦7, 716/m2 (US$19.17/m2). On the other hand, the price of land with primary infrastructure and adequate title in urban areas ranges between ₦30, 000/ m2 (US$73/ m2) to ₦200, 000/m2 (US$487/ m2) (CAHF, 2021: 194). The prohibitive price of land in the cities is generally caused by its higher development value and is further exacerbated by its scarcity caused by speculative sales and the government taking over them for luxurious development (Raschke, 2016: 6).

The financial intensiveness of housing development is beyond what private savings and retained business earnings can support (Omirin and Nubi 2007: 52), developers in the formal sector generally rely on loans from the deposit money banks for housing development despite the challenges of doing so. Access to housing finance from these sources is constrained by higher interest rates (more than 25%) and short tenure (average 3 years) (EFInA and FinmarkTrust 2010: 33, CBN 2020: 7). Furthermore, it is constrained by the impediments of the LUA because loans are usually secured with a valid Certificate of Occupancy (CoO). The length of time for registering land and the security of title (EFInA and Finmark, 2010: 37) arising from poor administrative protocols and poor land records (Omirin and Nubi 2007: 52, Adenikinju 2019: 26) are the banes of housing development in Nigeria.

Housing development cost is excessively high and more than half of the cost is attributed to materials cost (Iwuagwu Ben and Iwuagwu Ben 2015: 45). Two major factors are responsible for the high materials cost in Nigeria: the construction technology is predominantly cement and steel-based technology and these materials are not sufficiently available locally, hence, the need to import them. The cost associated with the importation of materials is as high as 50% to 55% (CAHF, 2021: 195); other related factors like bad roads, the high cost of petrol, import duty and the fluctuating exchange rates (Akanni and Oke 2012: 104, Ihuah 2015: 221, Adenikinju 2019: 26, Ajayi 2019: 232) drive up housing cost. To make matters worse, the government has failed to support local research as expressed in the policy (Uwaegbulam, Nwannekanma et al. 2019). Local production has not sufficiently scaled to an appreciable level that can compete with imported materials; the industry is bedevilled with fewer investments due to the high initial capital outlay in setting up factories, stricter licensing rules, high cost of finance, the high number of middlemen, and inefficient infrastructural facilities (Mojekwu, Idowu et al. 2013: 364, Uwaegbulam, Nwannekanma et al. 2019, Eboh 2021).

Involving the private sector to realise certain developmental objectives (KMPG 2021: 42) is no longer new, and it has become even more popular in the housing sector (Berry, Whitehead et al. 2006: 307). Although the footprints of private activities have been visible for a long time in Nigeria, the continuous decline of public resources and government performance has made their engagement in housing formally recognised. Their operation within the existing market is not impressive, however, maximizing private resources in affordable housing will require certain considerations that can help investors navigate the challenging environment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case study area

Nasarawa state is located in Nigeria’s North Central region with an estimated 2.6 million people (NASIDA n.d). It has 13 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of which Karu, is the closest, about 5km to Abuja, which is the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The relocation of the FCT to Abuja in 1991 and the proximity to the FCT brought sudden economic development to Karu (NSG 2019: 17, Oluwadare, Oluwafemi et al. 2023: 2), transforming it from a remote rural settlement to a vibrant urban area (Isma'il, Ishaku et al. 2015: 47). As a development corridor to the FCT, it has become the fastest urban area in Central Nigeria (Oluwadare, Olufemi et al. 2023:2), with an annual growth rate of 40% due to the influx of migrants from other parts of the country (ibid) and in particular, the FCT. In general, the strategic location of the state and its business friendly clime attracts entrepreneurs and many multi-national offices to the state. The state ranks the 11th most accessible state to start a business in Nigeria (NASIDA, n.d; NSG 2019: 23). These attributes have made Karu attractive to investors and workers alike and was one of the factors that attracted the development of the MFF estates in the area. Furthermore, compared to Abuja, the relatively low cost of housing is a major attraction to worker in the FCT (Oluwadare, Olufemi et al. 2023:3), and despite these positive attributes, Karu is unplanned and lacking in basic amenities and infrastructure (NSG 2019: 18, Oluwadare, Oluwafemi et al. 2023: 2-3). Housing is mostly rented and a few live in their own homes (Isma’il, Ishaku et al. 2015: 49). Generally, the most common types of rental residential housing include one bedroom flat to three bedroom flat, single room to two or more rooms in a compound. The average rental price for one bedroom flat hovers between ₦300,000 and ₦900,000 per annum depending on the location, age, and services provided.

3.2. Study design and instrument

Case studies are generally used to provide a practical example and contextual-based knowledge of a situation (Flyvbjerg 2006: 221-222), however, they are criticised for failing to generate generalisable findings based on their limitation of representativeness, which is even worse for a single case (Mariotto, Zanni et al. 2014: 360). Dismissing this criticism as a basis for rejecting the case study approach to research, Siggelkow (2007: 20) argued that a single case can be a powerful example capable of provoking powerful insight that might generally fail when considering a general feature shared among many cases. In support of this, Mariotto, Zanni et al. (2014: 364) declared that it is rather more desirable to base the choice of a case on its unusual characteristics, which can generate insights than on its representativeness. The MFF project possesses unusual features that can generate insight into the current subject; such features as its unique success in delivering affordable housing in Nigeria for over a decade without government support is an intriguing story that can generate insights for advancing the private-driven affordable housing in Nigeria.

The study focused on the experience of the MFF and some residents to draw some insights into possible considerations when designing appropriate enabling strategies for effective private sector-driven affordable housing. Hence, both the developer and some resident households of the estates were interviewed. Two different semi-structured interviews were administered to party. The interview for the developer was to ascertain the strategies employed to realise the affordable housing and comprised seven questions aimed to understand the motivation, objective, planning, organisation of resources, implementation, disposition of the houses, and the challenges encountered in the housing projects. On the other hand, the interview for the residents aimed to understand their experience of owning a house and comprised six questions to understand the process of acquiring and paying for the house, the benefits derived and the challenges experienced in doing so. Accounts from both provide complementary information that can be used for designing appropriate response to the affordable housing challenges in Nigeria.

The household participants were selected through snowballing and their willingness to be interviewed. First, the President of the Estate (PE) was interviewed and was asked to recommend participants. Subsequent interviews were conducted with the PE steering members, yielding the total of 12 resident households that were interviewed. The participants were interviewed separately during the visits to the site of the project in March 2020 and online when the Covid lockdown was enforced in Nigeria. All interviews were audio recorded with the participants’ consent. Accordingly, full transcripts of the recorded discussions were produced for each participant in line with the structure of the semi-structured discussion guide; they were analysed using thematic analysis with the support of Nvivo software. Thematic analysis allows for generating themes from the data against identifying them through preconceived themes. In this study, participants’ responses were first coded under the question they were responding to, thereafter, concepts conveyed through their narratives were extracted and grouped into sub codes. All data extracts demonstrating the same codes were grouped together, and repeated patterns of meaning in these codes helped to identify the themes. Thereafter, these themes were presented and discussed as complementary information to the responses provided by the MFF.

3.3. The history of Millard Fuller Foundation housing

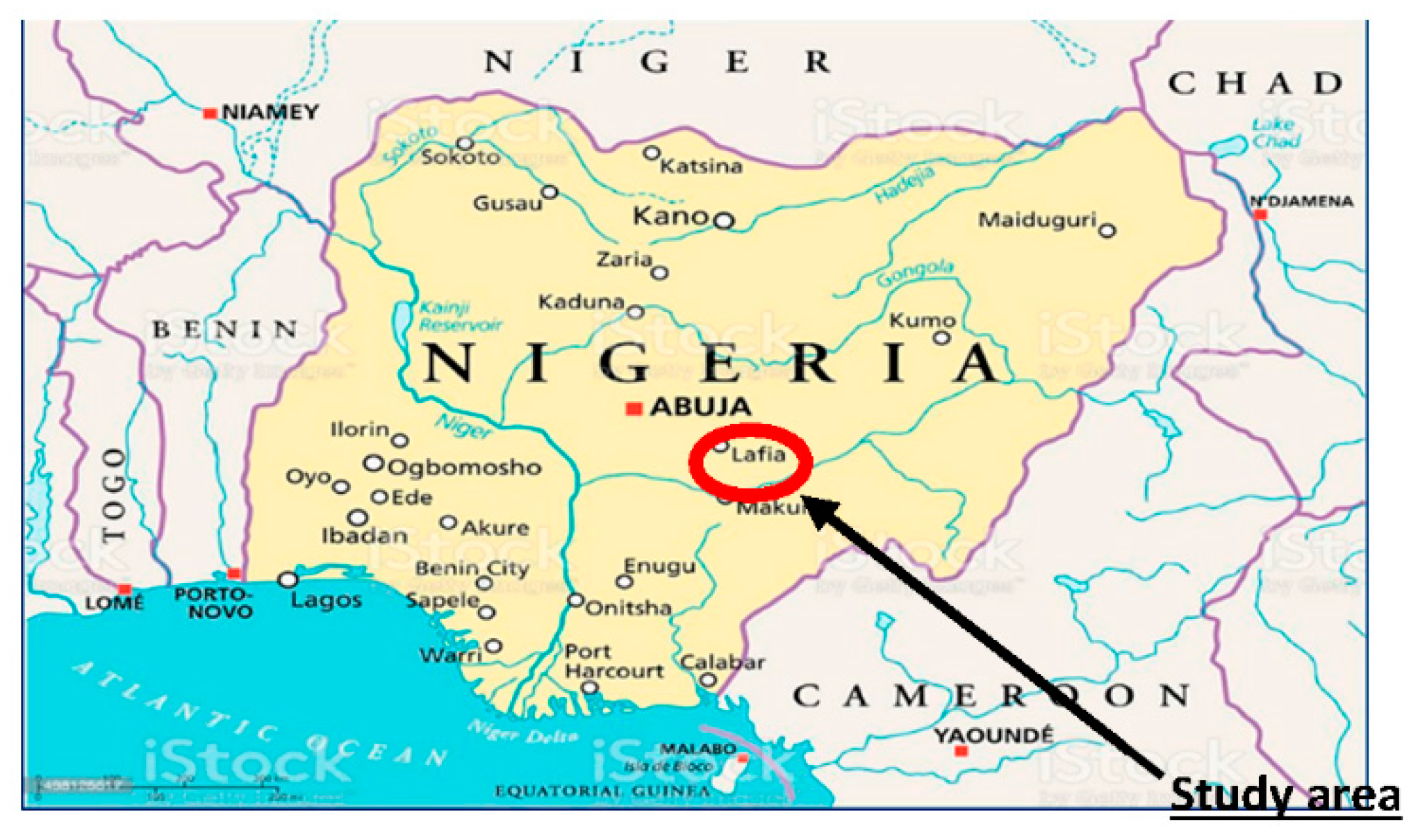

The Millard Fuller Foundation started as a non-profit house builder in 2006, to tackle the Nigerian housing deficit. In 2007, its first studio apartments were built with donor funds and sold at affordable prices. Subsequently, the desire to scale up production led Fuller to shift its strategy; currently, it employs short-term project financing (12–24 months) to provide for-profit residential housing developments for the middle to low-income groups (Raschke, 2016:11). The entire housing projects built by the organisation are located in Luvu-Madaki, Masaka in Nasarawa State of Nigeria: Luvu-Madaki is a village in Masaka community, a town that belongs to the district of Karu local government area of Nasarawa state. It is only a few Kilometres away from the capital city (Abuja) of Nigeria (see

Figure 1) and most workers who are unable to pay for the expensive accommodation in Abuja live and commute to work from there.

The MFF housing projects comprise mainly of studio apartments and one-bedroom apartments built as a semi-detached bungalow; however, there are other configurations as shown in

Table 5. Some of these houses were delivered in an incremen tal building fashion similar in concept to the Chilean firm ELEMENTAL (Ferreira n.d); thus the foundation offers shell and core houses that are completed on the outside but need additional finishing on the inside. Families or apartment owners can upgrade their studios to one-bedroom apartments and their one-bedroom apartments to two-bedroom homes.

The MFF projects are targeted at low-income buyers who were assisted to own a home through a convenient payment plan. As of 2020 when the data was collected, the Millard Fuller Foundation had finished more than 600 affordable housing units (

Table 5) and is scaling up its operation to deliver 600 units. Although the progress made since its existence may be considered slow due to several challenges, the MFF activities have contributed immensely to the development of the Luvu community, and its estates provide an affordable housing destination for most workers in Abuja.

Table 5.

Summary of MFF projects, based on data collected from a site visit of the project in 2020.

Table 5.

Summary of MFF projects, based on data collected from a site visit of the project in 2020.

| ID |

Project |

Number of units |

Cost (₦) |

Construction method |

Funding |

Design |

| 1 |

Fuller estate |

60 |

240,000 |

Concrete block and Nigerite produced drywall. |

Fuller Centre for Housing (FCH) USA |

Studio apartment started in 2007 with the last set completed in 2013 and fully occupied |

| 2 |

Camp Luvu I |

13 |

5.9m |

Concrete block construction |

Self-funded |

Three and four-bedroom apartments. |

| 3 |

Aso Fuller estate |

12 |

3m and 4m |

Concrete block construction |

MFF in partnership with Aso savings and loans ltd |

One and two-bedroom semi-detached bungalow completed and fully occupied. Started in 2009 and completed in 2010 |

| 4 |

Selavip I & II |

36 |

360,000 & 960,000 |

Concrete block and Nigerite produced drywall. |

Selavip and Etex group |

Studio apartments started in 2014 and were completed in 2015 |

| 5 |

Grand Luvu I |

268 |

1.65m, 2.9m and 3.9m |

Concrete block construction based on an incremental model2

|

MFF with funding from Reall, UK (loan at 5%) and bought over by FHF |

Studio expandable to one bedroom and one bedroom expandable to two bedroom semi-detached bungalow started 2015 and completed in 2016 |

| 6 |

Camp Luvu II |

32 |

3.6m and 5m |

Concrete block construction based on an incremental model |

MFF with funding from partner Reall |

studio and two-bedroom started in 2020 and ongoing |

| 7 |

Grand Luvu II |

400 |

2.9m and 3.9m |

Concrete block construction |

An initiative of FHF completely funded and handed over to it |

Studio and two-bedroom semi-detached bungalow, which took off in November 2017 and was completed in August 2018 |

4. Results

This section presents the results according to the stated objectives. Hence, each theme explored the target end-users of the MFF housing, whether the housing meets the end users’ needs, and the strategies adopted by the MFF to realise the projects.

Table 6 shows the profile of the end users that were interviewed and thus, provides a description of those targeted by the MFF projects. Apart from the fact that the table provides a clear picture of the housing stress of the residents of the estates, (in terms of their income monthly expenditure on housing), five major themes describe how the residents feel that the MFF housing has responded to their housing needs and are summarised in

Table 7. Finally, six themes describe the strategies adopted to achieve affordable housing. These themes are grouped under pre-development and development, and the post-development phases as shown in

Table 8.

4.1. The targets of MFF projects

This section addresses the first objective, which is to identify the targets of the MFF housing project and to ascertain whether MFF is addressing the housing need of the target groups. This will help to ascertain whether the policy goal to address the affordable housing crisis through the private sector is possible. Hence, the Fuller experience could provide valuable lessons to inform appropriate enabling strategies for private sector-driven affordable housing in Nigeria.

Table 6 and

Table 7 provide information on the profile of the MFF residents. It shows that based on the policy definition of the low income group (see

Table 2), the residents interviewed are within the low- middle income range with only four of them beyond this range. Although this number is not representative of the residents of the estates, we can safely assume that judging from the cost of these houses, only those within the low-middle income or above are catered for in this estate. Secondly, it shows that majority of the participants acquired from the government, which came with its challenges (see

Table 7).

Table 6.

The profile of interviewed residents.

Table 6.

The profile of interviewed residents.

| Resident |

Employment |

Monthly income (₦) |

Type of accommodation |

Number of persons in the household |

Payment cost and plan |

Residual income for other household expenses (₦) |

Cost of house (₦) |

| 1 |

Retired driver in a federal ministry |

Not disclosed |

Two-bedroom |

2 |

Paid in full with proceeds from the sale of land inheritance |

Not applicable |

3m |

| 2 |

Federal ministry employee |

Not disclosed |

Expandable studio and one-bedroom |

5 |

Paid 10% of the price and pays ₦50, 000 monthly for 7 years. |

Not disclosed |

4.55m |

| 3 |

A laid-off staff of a private bank and currently has no job due to age |

Not disposed |

Two-bedroom |

2 |

Borrowed from a friend to pay the initial 10% deposit and makes monthly payments to complete within 5 years |

Not disclosed |

3m |

| 4 |

Federal civil servant |

136, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

3 |

Originally ten years but shortened to five years and pays ₦60,000/month |

76, 000 |

3.5 m |

| 5 |

Federal civil servant |

125, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

3 |

50, 000/month for 5 years |

75 ,000 |

3.5m |

| 6 |

Federal civil servant |

40, 000 |

One-bedroom |

1 |

19, 500/month for 15 years |

20, 500 |

2.9m |

| 7 |

Federal Civil servant |

135, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

4 |

46, 000/month for five years |

89, 000 |

4m |

| 8 |

Federal Civil servant |

110, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

4 |

64, 000/ month for five years |

46, 000 |

3.9m |

| 9 |

Federal Civil servant |

116, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

5 |

Received as a gift |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

| 10 |

Federal Civil servant |

110, 000 |

Two + one- bedroom |

6 |

90, 000/month for five years |

20, 000, supplemented by wife (average of 10,000/month) |

6.8m |

| 11 |

Federal Civil servant |

100, 000 |

Two-bedroom |

6 |

50, 000/month for five years |

50, 000 |

4.2m |

| 12 |

Federal Civil servant |

180, 000 |

3 |

5 |

80,000/month for five years |

100, 000 |

7m |

4.2. To determine if the project meets the need of the low-income

This objective attempts to determine whether the MFF affordable housing meets the need of the low-income or the residents of the estates. Hence, the interview questions elicited the following information: ease of acquisition, the satisfaction derived and the turn offs of living in the estate. The themes emerging from participants’ narrative highlight important considerations when designing strategies for enhancing access to housing for the low income

Table 7.

Impact of MFF projects on residents.

Table 7.

Impact of MFF projects on residents.

| Resident |

Acquired from |

Ease of acquisition |

Satisfaction derived |

Discomforts or dislikes |

| 1 |

MFF |

|

Sense of ownership, security (have something to fall back on after retirement), comfort and freedom form harassment of the landlord, safe environment |

Poor salary, limited access to mortgage |

| 2 |

MFF |

|

Sense of ownership, no harassment, no paying of rent, sense of relief and comfort |

Unfinished building, bad road |

| 3 |

MFF |

|

Ability to own a house with small funds, friendly mode of payment, space around the house for garden, communal outdoor space for recreation |

Unfinished building, bad road, short payment period |

| 4 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

Bureaucratic processes and the payments involved |

No longer having to pay rent in lump sum, sense of ownership, no harassment, sense of pride, ease of payment |

Poor quality, not up to standard, small room spaces, low height, unable to fix ceiling fan with such height, wall absorbs water and destroys the painting, a lot of spending on transportation, low wage, more amenities at the city, failure to secure a mortgage, higher monthly payment due to short repayment period, inaccessible road, inadequate water supply |

| 5 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

Scheme plan poorly communicated by the government, uncertainty about their ownership status, difficult processing |

Better to pay flexible to own than rent, ease of ownership |

Rooms are small, will like to make some changes with the open space, spends more time commuting to work, afraid to loose job as a result, problem of water and electricity, bad road |

| 6 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

Federal government acquired at cheaper price from the developer and are selling at high prices |

Sense of comfort despite the inconvenience of lack of amenities, ease of ownership, security |

The spaces are small, spend more on transportation, inadequate water, and no electricity but that, is a national problem |

| 7 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

|

Ease of ownership and affordability of ownership |

Room spaces are small, delineation of spaces is not functional, location of the estate is far, traffic is usually heavy and ends up late at work, short amortisation period and poor communication resulted to higher monthly payment, no water, which adds to the cost of running the house |

| 8 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

The payment plan and status poorly communicated, the house was formerly cheap until the federal government bought them |

Sense of ownership and the flexible way to own a house, the cost of building from the scratch is high and cannot be achieved with low income, communal space for sports, security of the source of accommodation |

Thinks that low income housing means not adequate provision, location is inaccessible, no adequate water, no electricity |

| 9 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

|

|

Stress of transportation as a result of heavy traffic, spends a lot on transportation, lesser productivity, no electricity, stressful and costly to get to place of work |

| 10 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

|

Better to have mine than pay rent |

Longer time on the traffic to get to town |

| 11 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

Acquiring through government required lots of documentation and payments |

Flexibility to own a house, sense of ownership, cheaper to own than build from the scratch, safe environment |

Cheap material for construction, feels unsafe when it rains due to rain penetration, spends time commuting to work, no water, bad road, stress travelling on the road to work due to heavy traffic. Inadequate provision of water, power supply in Nigeria is problematic |

| 12 |

FHF through workplace cooperative |

|

Security, ownership, no longer paying rent, safe environment |

Inconveniencing to shorten the payment period because it increases monthly payment and salaries are poor. No amenities like water, it is inadequate for the number of residents |

The information in

Table 7 shows that majority of the participants are happy to own a home because of the security it guarantees and the freedom from the harassment that comes with renting, they value the ease of and the flexibility of owning a home that MFF has offered against doing so from the scratch due to low income. However, the high monthly payment towards their housing cost and short repayment period, poor design, including poor communication of ownership plan, location of the estate, inadequate amenities, and bureaucratic process of acquiring a home are some of the challenges of their journey towards owning a home in the MFF.

4.3. The Strategies adopted by MFF

This section describes the strategies adopted by MFF to deliver the affordable homes in Luvu, they also highlight the challenges to investment for which investors will need intervention to surmount to deliver affordable housing. MFF described some of the strategies they adopted to realise affordable housing in Luvu, and their narratives are coded under the relevant interview questions. The interview questions sought to understand actions carried out before and during construction to realise cheaper houses, and those adopted to enable residents to access them. Hence,

Table 8 describes the strategies adopted by MFF in two categories - construction cost reduction strategies and disposition strategies.

Table 8.

Strategies adopted by MFF.

Table 8.

Strategies adopted by MFF.

| Construction cost reduction strategies |

| Targets |

Method |

Reason |

Consequences |

| Land cost |

Sited project on the outskirts of Abuja |

(i). Land is cheaper in Luvu,

(ii). There is already an existing relationship with the community, which made the land transaction easier,

(iii). Nasrawa state has a good land registration system |

Location lacked services and infrastructure, so they were provided by the organisation and the cost was factored into the cost of development The end-users complained that there is no access road to the project location being far from local transportation and towns. |

| Design cost |

The design was limited to bungalows and comprised mainly studios and one to two-bedroom apartments, the room spaces are compact. |

To keep the cost of construction and the materials required for construction as low as possible. |

The cost of units was much lower but the end-users were dissatisfied with the outcome, so some of them had to make some changes to suit their design taste |

| Material cost |

Adopted the conventional construction materials in Nigeria eg Concrete block, concrete, cement etc. |

To keep the interactive cost of material, construction technology and labour low |

Because labour was available for this type of construction, the project resulted in the engagement of the local community, hence employment doubled. |

| Funding cost |

Obtained funding from Fuller Centre for Housing, USA, |

To reduce cost |

It resulted in fewer and slower production but cheaper apartments sold at no profit and interest (Table 5) |

| Used soft loan from Reall UK at a 5% interest rate. |

To facilitate production at a reduced cost |

Increased production but at an interest rate of 5% to cost of construction; the obligation to the loan was eventually paid for with a bulk purchase of the homes by the Family Homes Fund |

| Disposition strategies |

| Selling cost |

Set up a flexible payment plan |

To assist end-user to pay gradually |

Enabled end-users to pay gradually, which suited their variable income and encouraged payment with multiple sources of income |

| Completed a portion of the house and built the rest up to the concrete oversite (Figure 2) |

To reduce the cost of construction as well as the selling cost;

To enable the end-users to make decisions for their home according to their need and resources. |

Encouraged end-users to acquire their dream home in a less stressful manner. |

5. Discussion

This study investigated the MFF affordable housing estate at Luvu to draw lessons that may be useful in designing the enabling strategies for private sector-driven affordable housing in Nigeria. To achieve this, three objectives were pursued namely, to identify the class of people targeted by the project, determine the impact of the project on the residents’ housing needs, identify the strategies adopted by the MFF in delivering the houses. The first objective was to identify the class of people targeted by the project, which served to establish the basis for ascertaining that the measures adopted by MFF to achieve these houses can be used in designing enabling strategies for private-driven affordable housing in Nigeria. The finding showed that the majority that was interviewed are within the low-middle income and middle-income group, which means that the strategies adopted in this case may not guarantee affordable housing for the other groups (no income and low income) mentioned in the policy. Furthermore, the difficulties experienced by this group in terms of residual income after housing cost payment (see Table 6) raise questions about the adequacy of the income classification of the target groups in the present Nigeria circumstances (low minimum wage versus the ever-increasing price of fuel and products in the market, and the exchange rate). It implies that either the minimum wage is increased or the income capacity ranges of these groups are reclassified to reflect these circumstances. The second objective was intended to ascertain whether the housing needs of the residents were met by the MFF project, using the attributes of housing described in UN-Habitat (2011: 10) as a benchmark. Hence, based on the criteria of design, location, basic provisions, and monthly housing payment, the MFF projects have not performed well.

In respect to the strategies employed by MFF in the development of the houses, these are described in the following themes, reflecting areas within and after construction where developers may require intervention to deliver affordable housing (see

Table 8).

5.1. Land cost

Land is crucial for delivering housing in general and affordable housing in particular (Lawal and Adekunle, 2018: 3), and both land cost and location are important determinants of the cost of housing (UN-Habitat, 2011: 34). Since the land cost can account for a sizeable share of the housing cost, (Mc-Kinsey 2014: 7, El-hadj, Issa et al. 2018: 162), it means that some amount of reduction in the cost of housing can be guaranteed through the management of the cost components of land.

Two essential features of the land are important for affordable housing and are also interrelated: affordability and availability. The availability of land in a good location can affect its affordability and when land is affordable, it is unlikely to become readily available in accessible locations (El-hadj et al. 2018: 109), thus, the cost of providing the infrastructure and services required to enhance the accessibility to land are important considerations when siting affordable housing.

The cost of land consists of the cost of acquisition, the cost required to secure land tenure, including the simplicity of the processes and the procedures that are involved (Lawal and Adekunle, 2018: 3); these considerations will naturally move private developers1 to site housing developments on low priced land on the urban periphery as a cost-saving strategy for their housing development (UN-Habitat, 2011: 38).

”Ok, so let me start with the location, we are essentially located here because land is cheap, there is a historical factor as well; the HFH was working in this community so we already knew the people, and it was easy to buy land from them and to do other projects but essentially, the bottom line is that land is cheap in this area...” [MFF]

Therefore, the choice of Luvu as a location for the projects came at a cost for both the MFF and the residents; the MFF bore the cost of providing basic infrastructure and services, which eventually increased the cost of construction that was transferred to the end-users2 (El-hadj et al., 2018: 109; Makinde, 2014: 60). Expectedly, this action did not guarantee a pleasant experience for the end-users who are not only cost burdened but have to deal with the inconveniences associated with living far from the towns and commuting to them 3

- 2.

‑Ok. Because we are working here far away from town, really infrastructure doesn’t exist, we have had to provide all the needed infrastructure…. so essentially we have to do everything and we cost it, and the people at the end of the day, pay for it, it’s in the cost of the house, so that cost includes all the infrastructure, land, construction and a small profit element in it... [MFF]

- 3.

“Another challenge is the distance from my workplace. The location of the estate is far, most of the people living in this estate work in Abuja,…so we have to travel a bit and be held in the traffic before we get to the office. Some of our bosses understand where we live and they don’t get angry but some don’t want to understand and they issue a query…” [Resident 7]; However, it is far from the city centre and where I work, and I spend ₦2,600 daily commuting to work every day…[Resident 4].

Three lessons are distinct and they also reveal the systemic flaws that hinder private performance; first, the lack of affordable land in accessible locations can drive investors to make unhealthy choices for their investments; this highlights the importance of affordable land and the need to improve land value through sites and services programmes (El-hadj et al., 2018: 147). Secondly, despite trading good location for affordability, accessibility has a significant effect on the end-users; this assertion aligns with the analysis of Mc Kinsey (2014: 7), which implies that pursuing a reduction in land cost at the expense of good location is detrimental to affordable housing efforts and will negatively impact the end-users residual income. Finally, the cost of providing services on land has a significant effect on the overall housing cost and the developer will normally transfer the cost to the end users. Hence, to enable private investment in affordable housing, the provision of infrastructure and services must be pursued by the government.

5.2. Cost of design

Developers who build affordable housing face a lot of hurdles like expensive labour and materials, onerous regulations and approval, which together with the tight budget constraints make affordable housing development a daunting endeavour. The cultural belief that the benefits of good designs should be reserved for those who can afford them is popular, hence it is not uncommon to associate low-income housing with banal and depressing designs (Wright 2014: 71). This is demonstrated in the case project where the desire to achieve affordable construction was accomplished through designs that are simple, basic and minimalistic4.

- 4.

“…our designs as I said are very basic, eventually, we are working around a single-room model. …and we have typical designs for studio apartments, one-bedroom apartments, we have designs for two-bedroom apartments, we hardly do three-bedroom,… it’s just because of the cost, we want to stay below the 5 million naira mark. We have bathroom facilities, we keep it minimal, usually just one bathroom for the house…” [MFF]

However, El-hadj et al. (2018: 167) laud optimised design as a more sustainable way to minimise cost, which also harmonises with the MFF vision for its future development5.

- 5.

“…eventually we are working around a single-room model. We have a 3.6m grid which is 12ft, most of our buildings are just 12 ft, the intention is that with time we will modularise these designs so that we can begin to create or mould prefabricated components that can be just joined together, so that’s the basic grid”…[MFF].

As much as MFF achieved a reduction in the cost of construction through minimalistic designs, they may have comprised on quality and comfort in the process as five of the interviewed residents expressed dissatisfaction with the design outcome (see

Table 7). Their willingness to make certain changes to their homes

6 suggests that housing is not only about the provision of the basic structure or shell but also about providing the satisfaction and comfort that the end-users desire for their homes (UN-Habitat 2014: 3, Wright 2014: 70, Garton, Grimwood et al. 2017: 2):

- 6.

“...Interestingly enough the market doesn’t like it, they want aluminium windows, they want sliding windows, they want to be modern even though half of the opening is blocked, that’s the irony. Sometimes, they take the windows out and put their windows, they are allowed that but for now, and we are still sort of sticking to our louvre window…” [MFF]; I’ll definitely make some changes. The room is not big, it's quite small when you compare what we have here to others particularly in some estates, if I have the opportunity, I will definitely make some changes [Resident 5]; the estate developers also take advantage of the fact that their activities are not being supervised to use substandard materials to construct the house. For example, once it rains, my house absorbs water and despite painting the inner walls, the paint peels off. So we now use wall tiles to the height of the room to make sure that the water doesn’t penetrate and affect the furniture in the room…[Resident 4]

Finally, the actions of MFF strengthen the already established belief that design variables affect the cost of construction (Seeley 1996: 31); so, while efforts may target reducing cost for the developer, they should seek to satisfy the needs of the end-users as well. Achieving harmony between these two interests will lead to a successful affordable housing programme; on the other hand, end-users tastes vary considerably so, affordable housing strategies may have to lean towards enabling end-user-driven housing initiatives.

5.3. Using conventional materials vs the local counterparts

In Kenya, materials account for about 40% of the total construction (El-hadj, 2028: 169), but this can be higher in countries that import a majority of their materials. In Nigeria, up to 55% of the materials cost of construction is due to importation (CAHF, 2021: 195). Under such circumstances, the popular opinion on the subject of affordable housing will strongly apply; this opinion advocates for the use of local materials and local production, which will not only guarantee large-scale affordable housing development (Acheampong, Hackman et al. 2014: 2, Iwuagwu Ben and Iwuagwu Ben 2015:47) but will also improve the sustainability of the housing development process (El-hadj et al., 2018: 170).

Despite the popular view on this subject, the MFF used mainly the conventional materials that are readily available because construction in Nigeria is essentially cement-based (Olajide Olorunnisola 2019: 57). Aggregates are naturally sourced but the raw materials for cement production are mostly imported; furthermore, local cement production is low and importation is restricted, leading to sharp increases in the price of cement (Ibid: 59). In light of these challenges, the cement-based model is not only unaffordable but also unsustainable and the importance of research into local materials and the encouragement of local production are once more highlighted. Unfortunately, the circumstance of Nigeria, given the fact that research into, and the production of local materials are yet to fully develop into an appreciable scale, does not guarantee the benefits of that option, hence the MFF was constrained to use these conventional materials, which are readily available and can engage the local labour7:

- 7.

“We have in the past used the compressed hard block technology in my last organisation HFH, we did a lot of houses with compressed hard blocks, and we discovered that yes it was cheaper than concrete blocks but we were paying more for labour. … so at the end of the day, the cost kind of balanced out and we saw that there wasn’t that more of an advantage in using compressed hard blocks or stabilised blocks than in using concrete blocks…but essentially we are working with the normal concrete blocks technology that everybody works with, it’s known, it’s available and also it engages a lot of local labour because we see our work not just as construction but also empowering the community so the more people that can be empowered in the process of the housing delivery, the better for the project…” (MFF)

The MFF position, in this case, implies that the use of local or innovative materials and technologies should follow a thorough assessment of the local circumstances; this is because its use of the compressed hard block technology in their past project without adequate consideration of the availability of the appropriate labour made no difference in the cost of construction; besides, the fact that the arrangement resulted to fewer labour engagement is a bad testimony for construction projects, which have the potential to generate both employment and local economic development (UN-Habitat 2014: 20). Therefore, the benefits of local materials in housing should be holistic, first, research should address the issues of availability of raw materials, the feasibility and viability assessments, which must precede local and large-scale production, and complemented by corresponding manpower training.

5.4. Cost of funding

An impediment to supplying affordable housing is the lack of funding for developers (El-hadj et al., 2018:201) and since housing is capital intensive, developers (Particularly small to medium-scale ones) will find it difficult to support such an investment with insufficient equity; hence, they will require financial support from banks and other sources to do so. However, lenders are unwilling to provide the amount of money that is required to close the affordability gap to developers without the necessary risk capital; as such, tight lending requirements that they introduce for their security only limit access to funding for many developers (Ibid: 202)

The different funding arrangements and sources adopted by the MFF had different impacts on the projects, they highlight the key considerations when designing funding arrangements for affordable housing. Free funding or subsidies expressed as donor funding in the MFF’s case may be an attractive source of funding since it comes at no cost to the developer, however, it is unlikely to come in the amount and frequency that will scale up housing development (Blumenthal, Handleman et al. 2016), and is, therefore, unsustainable for funding large-scale projects. There is no doubt that the free fund from the Fuller Centre for Housing in the USA helped to realise 60 studio apartments that were sold at no profit or interest8; the cost of the studios was considered too affordable such that they were quickly sold out and the organisation saw the need to scale-up through a different funding source9. On the other hand, the REALL UK loan scaled up the production of housing but it came with an additional burden of repayment:

- 8.

“So as I mentioned, the first project we did is zero profit, zero interest project with the FCH in the US, which was our first project that was financed entirely by donor funds; then we now got a loan from REALL UK to begin the Grand Luvu project it was a soft loan at 5% interest rate. Grand Luvu II on the other hand, was financed partly with equity, and then we were being paid by FHF in instalments. That’s how we were able to finish Grand Luvu II … So they sort of took it over, they paid us and just took it. Then the Grand Luvu I which was financed by REALL, they bought it when it was completed,” [MFF]

- 9.

“…it’s an apartment that cost about 360,000 naira and people wondered: can this be real in Abuja? And they asked: is that the cost of the rent or the cost of the house?...the challenge we had when people came to our doorstep and found it to be so cheap is that the whole of Abuja now ended up on our doorstep and with just donor funding coming in, we could not build more than what we had on hand so most of the people had to be turned back…”[MFF]

Accounting for any economic changes that would have taken place between the period of the development of the first and second studio apartments, the impact of the loan on the selling cost of the houses is visible; at ₦4.55m (

Table 5), and with the residents not qualified for a mortgage

10, they must find it considerably difficult to make monthly payments and cater for other basic needs (see

Table 6).

- 10.

“ok, initially, we were told that we should pay 10% of the money, after the 10% of the money, they can give you the key to the house and you start paying may be through a mortgage, but for my case, I didn’t go through mortgage because, by that time, the mortgage did not accept the percentage I applied for…” [resident 2]

Two distinct features are important in designing funding arrangements for affordable housing, first, it is indisputable that using free funds led to the delivery of houses that were much more affordable, however, the rate of development (

Table 5) compared to when the Reall UK loan was used is low. This means that using free funds or subsidies alone is not a realistic and sustainable funding option because, besides funds being limited, the process of awarding them is competitive and they may take time to release in the amounts that will guarantee speedy delivery of the project (Blumenthal et al., 2016).

Table 5 clearly shows that the time taken to deliver 60 studio apartments is much longer than the one-year period required to deliver about 268 units (comprising studio apartments and other types of dwellings) with a loan.

Secondly, although faster production is guaranteed with a loan funding arrangement, however, the cost of that option is an important consideration when choosing to use it. The interest rate, amortization period, and the terms for accessing the loan can affect the development cost and subsequently the disposition. Again, the investors are very particular about making quicker returns since it will help discharge them of their loan obligations more quickly. However, the income capacity of the low-income end-users increases the risk involved in serving the market, and the requirements for accessing mortgage loans are much stricter, which has serious consequences for the investor. Although this consequence was mitigated by the bulk purchase of its homes by the Family Homes Fund (FHF) 8, which enabled them to pay off the REALL loan, planning for affordable housing should be deliberate and not left to chance; this means that improving the end-users income capacity through appropriate funding mechanism should be an important consideration in planning affordable housing programmes (Blumenthal et al., 2016). Alternatively, bulk buying of houses by the government can help facilitate quicker returns for the investors and allow for a flexible disposition of the houses to end users.

5.5. Flexible payment plan

It is illogical to invest in affordable housing if the disposition cannot be guaranteed. Investors can only stay in business if they can make returns on their investment and this can be achieved if the end-users have the financial capacity to effect the demand for housing. The low-income capacity of the target end-users limits access to housing, which is detrimental to investment. To facilitate access that will guarantee quicker returns for the MMF, a flexible payment plan and an incremental construction approach for the projects were adopted. The original design of a flexible payment plan required the buyers to pay an initial 10% deposit and complete the rest through monthly contribution over a period of time. Flexible payment pattern was the major attraction for the residents and the fact that they were contributing gradually towards owning a home was enough motivation for them to make such committment

11 (see

Table 7). This method of paying for housing aligns with the UN-Habitat (2012: 27) strategy for enabling the low-income end-users towards homeownership in line with their variable income.

- 11.

”…but MFF will only ask you for a percentage, when you pay that percentage, you will be given the key to your house without completing your payment and then, they spread out the balance over a period of time and that for me is the greatest help they can give to the less privileged” [resident 2]; “Some work and some don’t, so it’s not easy for somebody to count 2 million, 3 million easily like that to pay, instead of that, they will have discouragement” [resident 3]; “the salary paid to workers is nothing to write home about but if you are removing every month you may not feel it” [resident 1]

Despite the flexibility that the payment plan offered, the residents particularly found making the initial deposit difficult due to low income and no savings12, which clearly denotes low minimum wage; in addition to that, many did not qualify for a mortgage loan13 and even after five years, most of them had not got a decision on their mortgage application resulting in further negotiation with the FHF to draw an alternative payment plan. Therefore, most of the participants now pay monthly from their salary over five years despite the inconvenience that it would cause them14. It is evident in Table 6 that almost all the participants are shelter burdened, paying more than 30% of their salary on housing. Despite this, most of the participants expressed a strong desire to maximise the life time opportunity offered by the MFF housing to become a house owner, hence, many are sacrificing other needs for housing, while others are exploring different means like borrowing, using gift donations and supplementary informal incomes to fulfil this obligation.

- 12.

“…Getting the initial payment was the greatest problem because I did not have money saved anywhere…so I cried to a sister and … she asked me to send my account number, I was like, is this true? … The initial payment is most people’s problem but compared to where you will buy a piece of land and build and enter, it’s still better…”[resident 3]

- 13.

“… I didn’t go through the mortgage because they did not accept the percentage I applied for. …in my own case, we own the whole building…so, we are paying ₦50,000 in a month because the building was given to us at ₦4.something million [So you and your husband are contributing to pay?] yes [that means you are also a government worker] my husband is a government worker but I do business ” [resident 2]

- 14.

At a point because I took it in 2018 but they're still on the process of the mortgage, so when I now decided to opt out from the beginning of this year and I said OK, thank God, I know I can, at least afford it from my salary and I decided to pay the money for five years and get over it even though it is not going to be easy, but then I said that instead of waiting for mortgage endlessly and afterall, it’s a business and they are not giving you free. Though it might be painful, but I just decided to endure it and make the payment within five years.₦ So that is the plan

Three lessons can be drawn from this theme. First, the need to own a house overrides every consideration as Udechukwu (2008: 182) rightly asserts; therefore, despite the inconvenience, participants are willing to make sacrifices to realise this ambition. This means that housing efforts that tilt toward homeownership may be more acceptable than its rental counterpart. Secondly, as much as flexibile ownership is a more convenient way of paying for housing for the low-income, monthly payment plans should be designed affordably in line with their income to ensure that payment to housing cost will not impact negatively on the residual income. Therefore, longer repayment period may be required to reduce the monthly contribution and thus, the cost burden as resident 7 analogy suggests.

- 15.

At first, it was going for like 10 years. To make it like easier for us so that the amount they will be deducting from our salary will not be too cumbersome. But in the long run, an issue arose that made them teduce the number of years we're going to pay it for. So, they reduced it to five years… Before, when it was for the period of 10 years, we were paying like ₦27,000 naira, but now that it has reduced to five years, we are paying like ₦46,000, something [Resident 7].

Thirdly, from the responses, participants did not qualify for the NHF mortgage loan due to their low income; again, those of them who did not receive any decision to their loan application, given their monthly salary (

Table 6) would still not have qualified for a loan (see information in

Table 3). In this case, two considerations may apply. First, if the NHF mortgage system should still be considered an enabling mortgage option for the low-income earners, it will need to recognise other supplementary income sources in the loan origination procedures as a strategy for enhancing access to it (Makinde, 2014:54). Secondly, the case study has proved that flexible payment to housing is possible with direct deduction of payment from the source if appropriately designed and managed to prevent defaulting in payment. Above all, flexible payment plans, whether through mortgage or direct deduction from salary source should be affordable, which can be achieved by extending payment period to reduce monthly contribution.

5.6. Incremental housing pattern

The underlying reasons for the adoption of an incremental development approach were to reduce the cost of development for the MFF and the initial cost of acquiring a suitable home for the end users16. The idea is to encourage access for families to their dream homes without the inhibitions of their income since they can gradually build or expand their homes based on their resources and need. In consideration of certain changes made by the residents to their home6, incremental housing implemented by the MFF will foreground the needs of the inhabitants rather than the developer since families can take responsibility and care of aspects of housing, which they are in the best position to take in line with the principles of incremental housing (Hasgül 2016: 20). In places where this approach was successfully implemented, for example in Chile, basic, core structures were built and the individuals built up the space according to their pace and resources (Ferreira, n.d). In MFF case, this was achieved by building up the core of the house and leaving another portion at the concrete oversite level to allow for expansion as endusers deem fit and at their convenience.

- 16.

“… so essentially we are in incremental housing, so the idea is that you may not have all the money to do your two-bedroom unit but you can start off with what you have, start off with the studio apartment, with time, put another room more, with time put another room more … Actually one of the designs you might see is the studio apartment and the foundation made already for the additional room, then you also have the one bedroom unit that’s expandable to two bedroom unit, so essentially that’s what we are doing,” [MFF]

6. Conclusions

As the housing deficit continues to increase despite adopting a private sector-driven housing approach, the need for improving the existing strategies for effective private performance becomes imperative. By studying the MFF projects, on account of the desirable attributes, the study drew from the lessons to highlight possible considerations for advancing private sector-driven affordable housing in Nigeria. Hence, it establishes the following:

That the MFF projects at Luvu catered specifically for low-middle-income and middle income earners and that unless the National Minimum Wage is improved, strategies adopted in this case may not satisfactorily advance the delivery of affordable housing for this income groups, much less cater for the no-income and low-income groups;

Developers may likely adopt practices that will reduce the cost of investment and these practices will generally target the construction cost components like land, materials and design;

The decisions made by developers with respect to land and the design of the building may adversely affect end users’ satisfaction, however, an incremental building approach may help to preserve both the developers and the end users’ interests in terms of a reduction in the cost of investment and the freedom to make choices for their homes based on their taste and resources respectively;

Embarking on a widespread infrastructural development will make development land available in all locations so that affordable housing development can no longer be confined to locations where services are lacking;

Bulk purchase of housing units can help private developers make quicker returns on their investment and release them from any loan obligation as well as facilitate the disposition of houses on flexible terms to the end users;

Access to the NHF mortgage can be improved for the low income earners by recognising other supplementary incomes in the loan origination procedures;

Flexible repayment plans should incorporate longer period of payment to reduce monthly payment for housing and increase residual income for the end users.

Future Research

Articulating enabling strategies for housing will be beneficial to both the government and private investors. Government resources are constrained, therefore, direct intervention might be impossible; the insights generated in this paper are both revelatory and instructive. Policymakers can assess the existing strategies in light of them and can be guided to design specific interventions based on the concerns identified in the paper. The paper also recognises that effective enabling strategies should incorporate efforts for harmonising the needs of private developers and end users, hence, future research should lean towards exploring other harmonising features that will encourage more robust enabling strategies for private-driven affordable housing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L. N.; methodology, L. N., L. R., and L. K..; validation, L. R., and L.K.; formal analysis, L. N.; investigation, L. N.; resources, L.N.; supervision, L.R. and L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.N.; writing—review and editing, L.N., L.K., and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to commitment to preserve the confidentiality of participants used for the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acheampong, A.; et al. Factors inhibiting the use of indigenous building materials in Ghanaian construction industry. Africa Development and Resources Research Institute Journal 2014, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Adedeji, I.; et al. The challanges in providing affordable housing in Nigeria and the adequate sustainable approaches for addressing them. Open Journal of Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, S. A. O.; Agbola, T. Housing Affordability and the Organized Private Sector Housing in Nigeria. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2020, 8, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegun, O. B. and A. A. Taiwo (2011). "Contribution and challenges of the private sector's participation in housing in Nigeria: case study of Akure, Ondo state." Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 26(4): 457-467. [CrossRef]

- Adenikinju, A. F. Bridging housing deficit in Nigeria: Lessons from other jurisdictions. Economic and Financial Review 2019, 57, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Airgood-Obrycki, W.; et al. "The rent eats first": Rental housing affordability in the United States. Housing Policy Debate 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Addressing Housing Deficit in Nigeria Issues, Challenges and Prospects. Economic and Financial Review 2019, 57, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni, P. O.; Oke, A. E. An assessment of trend in the cost of building materials in Nigeria. Environmental Research Digest 2012, 8, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, A. A.; Amadu, L. Urbanization, cities, and health: The challenges to Nigeria - A review. Ann Afr Med 2017, 16, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, M.; et al. Involving the Private Sector in Affordable Housing Provision: Can Australia Learn from the United Kingdom? Urban Policy and Research 2006, 24, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, P., et al. (2016). "How affordable housing gets built." Urban Institute. 2022. Available online: https://urbn.is/2wOouox (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- CAHF (2019). Housing finance in Africa 2019 yearbook. Johannesburg, South Africa, Centre for Affordable Housing Finance.

- CAHF (2020). Affordable housing in Nigeria: Market shaping indicators. Nigeria: 1-12.

- CAHF (2021). Housing finance in Africa: A review of Africa's housing finance market. Johannesburg, South Africa, The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

- CBN (2020). Mortgage. FSS International Conference. Abuja Nigeria, Central Bank of Nigeria.

- Chime, U. (2016). Challenge of housing affordability in Nigeria. 32nd African Union for Housing Finance 2016 Conference. Abuja.

- Conteh, A., et al. (2020). "A new insight into the profitability of social housing in Australia: A Real Options approach." Habitat International 105: 102261. [CrossRef]

- Eboh, C. (2021). Nigeria raps dominance of large cement firms hampering economy. Reuters. Online, Reuters.

- EFInA and FinmarkTrust (2010). Overview of the housing finance sector. Nigeria, Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access: 1-52.

- El-hadj, M. B., et al. (2018). Housing market dynamics in Africa. London, UK, Springer Nature.

- Elegbede, O. T.; et al. An Appraisal of the Performance of Private Developers in Housing Provision in Nigeria. (Redan as a Case Study). International Journal of Advances in Chemical Engineering and Biological Sciences 2015, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, K. (n.d). Introduction to Architecture. Online, Creative Commons Attribution Non commercial.

- FGN (2012). Draft National Housing Policy 2012. Nigeria, Fedral Governemnt of Nigeria.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). "Five misunderstandings about case study research." Qualitative Inquiry 12(2): 219-245. [CrossRef]

- FMWH (2020). "Welcome to the national housing programme.". Available online: https://nhp.worksandhousing.gov.ng/ (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Garton, G., et al. (2017). New housing design. House of Common Library. United Kingdom, House of Common Library.

- Ghebru, H. and A. Okumo (2016). Land administration service delivery and challenges in Nigeria: A case study of eight states. NSSP Working Paper 39. Washington, DC., International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Hasgül, E. (2016). "Incremental housing: A participation process solution for informal housing." ITU AZ 13(1): 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C. and D. Mc Cue (2018). "Is there a better way to measure housing affordability?" Joint Centre for Housing Studies of Havard University. 2022. Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/is-there-a-better-way-to-measure-housing-affordability#:~:text=The%20residual-income%20approach%20to%20housing%20affordability%20The%20residual,include%20food%2C%20health%20care%2C%20transportation%2C%20and%20child%20care.

- Ibem, E. O. (2011). "The contribution of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) to improving accessibility of low-income earners to housing in southern Nigeria." Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 26(2): 201-217. [CrossRef]

- Ihuah, P. W. Building materials costs increases and sustainability in real estate development in Nigeria. African J. Economic and Sustainable Development 2015, 4, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isma'il, M.; et al. Urban Growth and Housing Problems in Karu Local Government Area of Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Global Journal of Research and Review 2015, 2, 45–57. [Google Scholar]