Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights:

- NTO heat-treated 8 h has a less ordered structure and more surface contamination.

- After oxidation, some Na+ ions are trapped in NTO heat-treated 8 h structure.

- The increase of the calcination time leads to higher electrochemical performance.

- The charge transfer resistance evolution in NTO depends on the reversible formation/deformation of Na4Ti3O7 phase.

- The Rt evolution depends on the reversible formation/deformation of Na4Ti3O7 phase.

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Structure Characterization by XRD

2.3.2. Particles Size and Morphology

2.3.3. Surface Chemical Characterization XPS

2.3.4. Cell Preparation and Electrochemical Tests

2.3.5. Operando X-ray Diffraction

2.3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

3. Results and Discussion

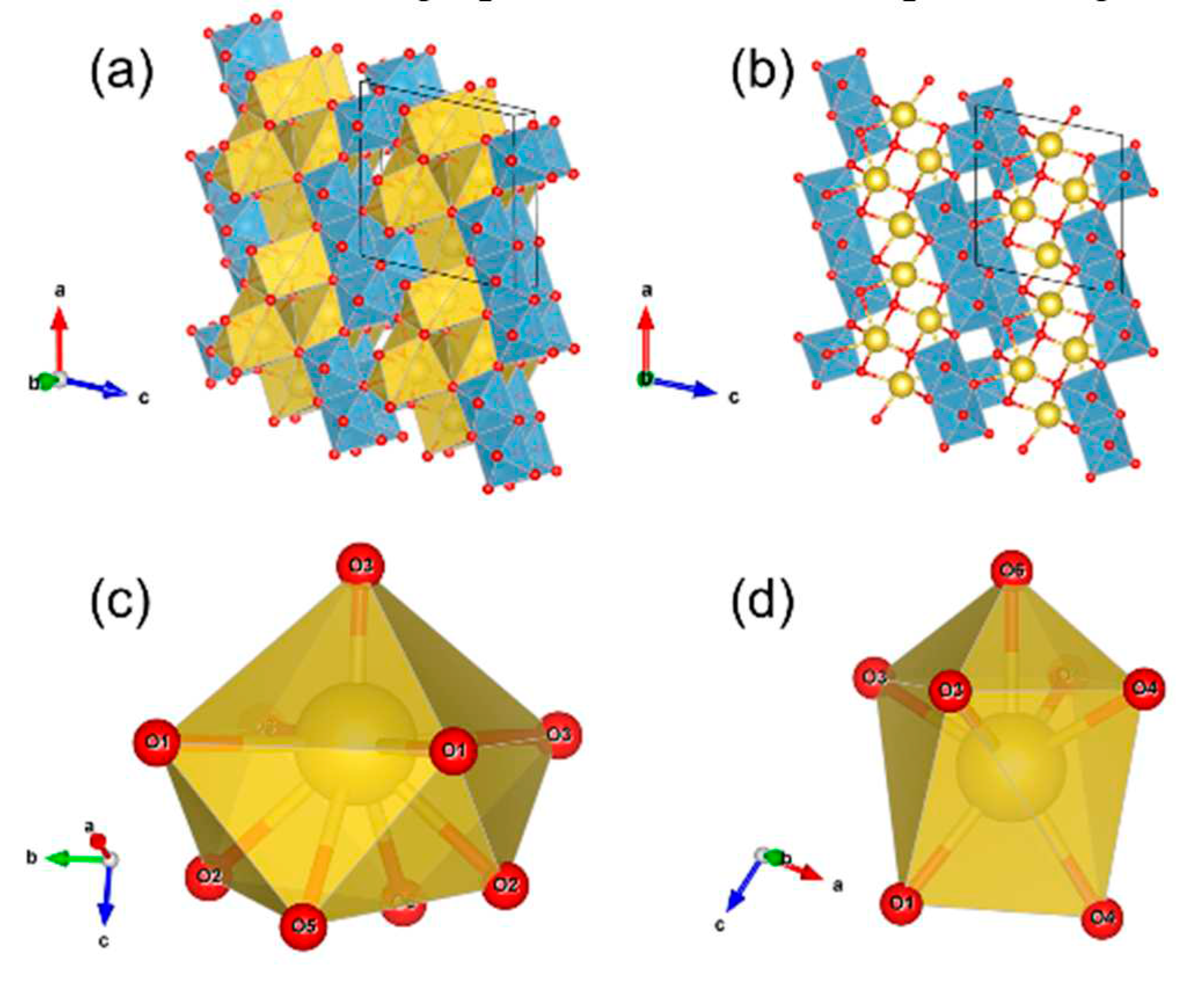

3.1. Structural Properties of the NTO Pristine Materials

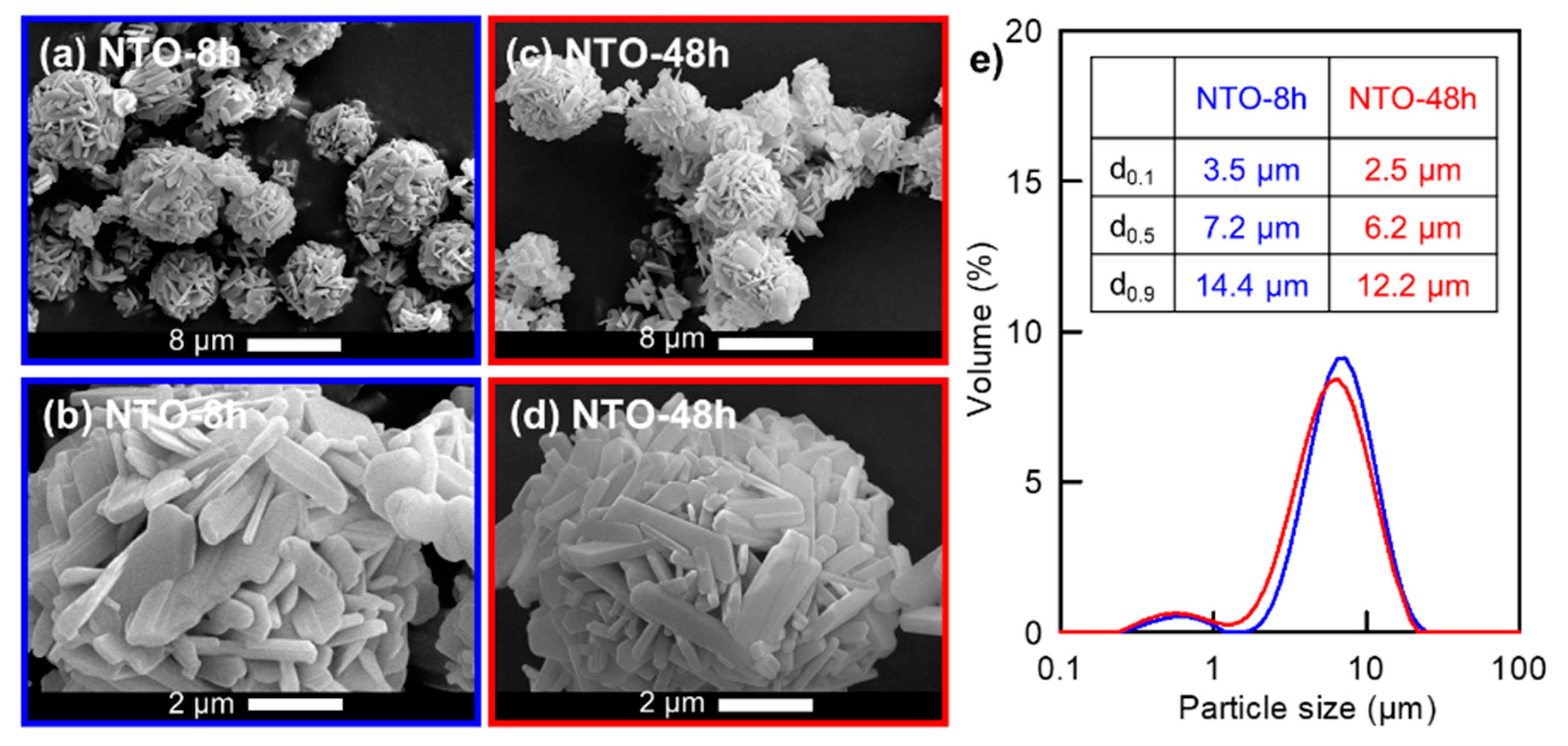

3.2. Microstructure of the Raw Materials

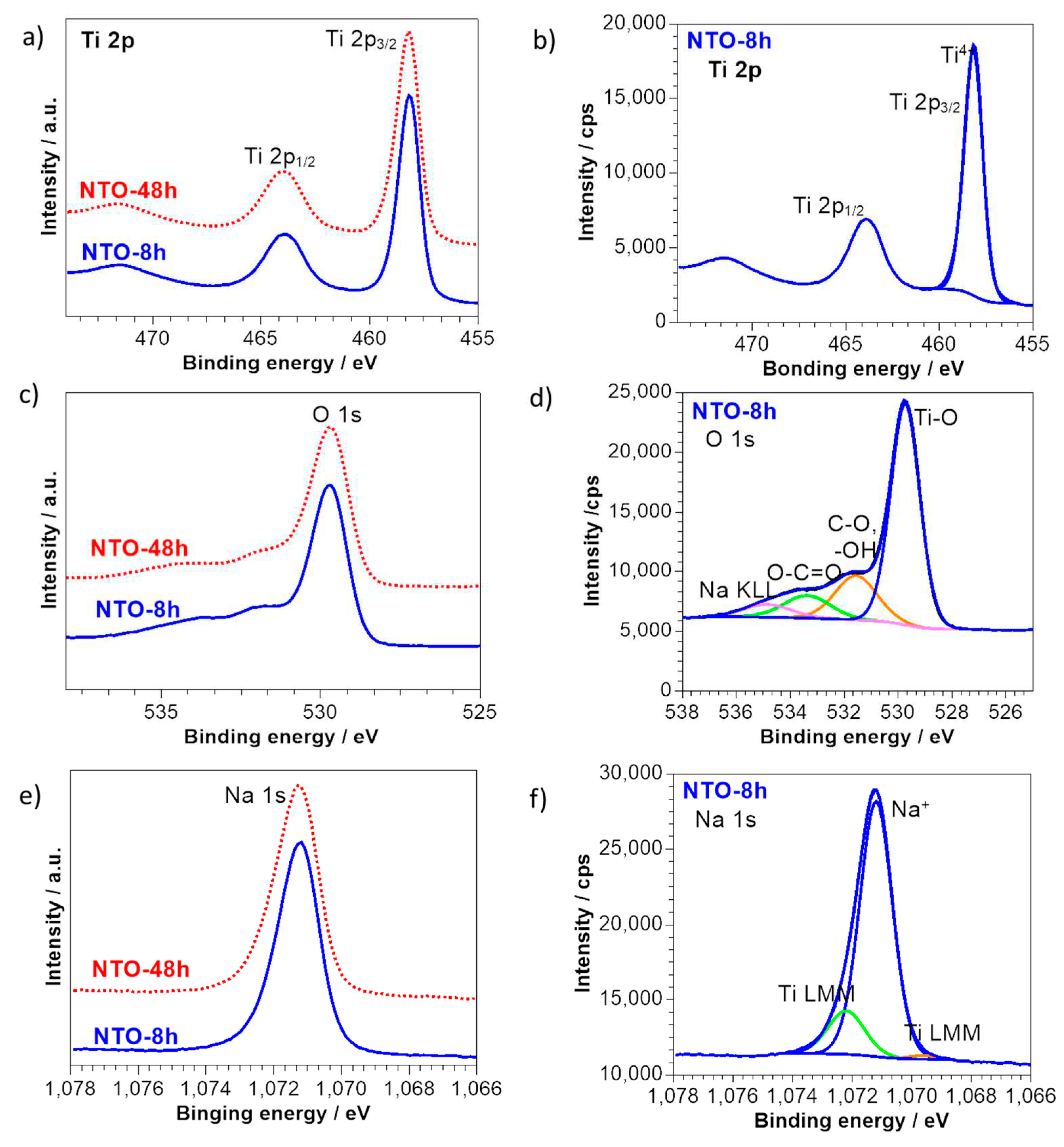

3.3. Chemical Characterisation by XPS

3.4. Electrochemical Properties

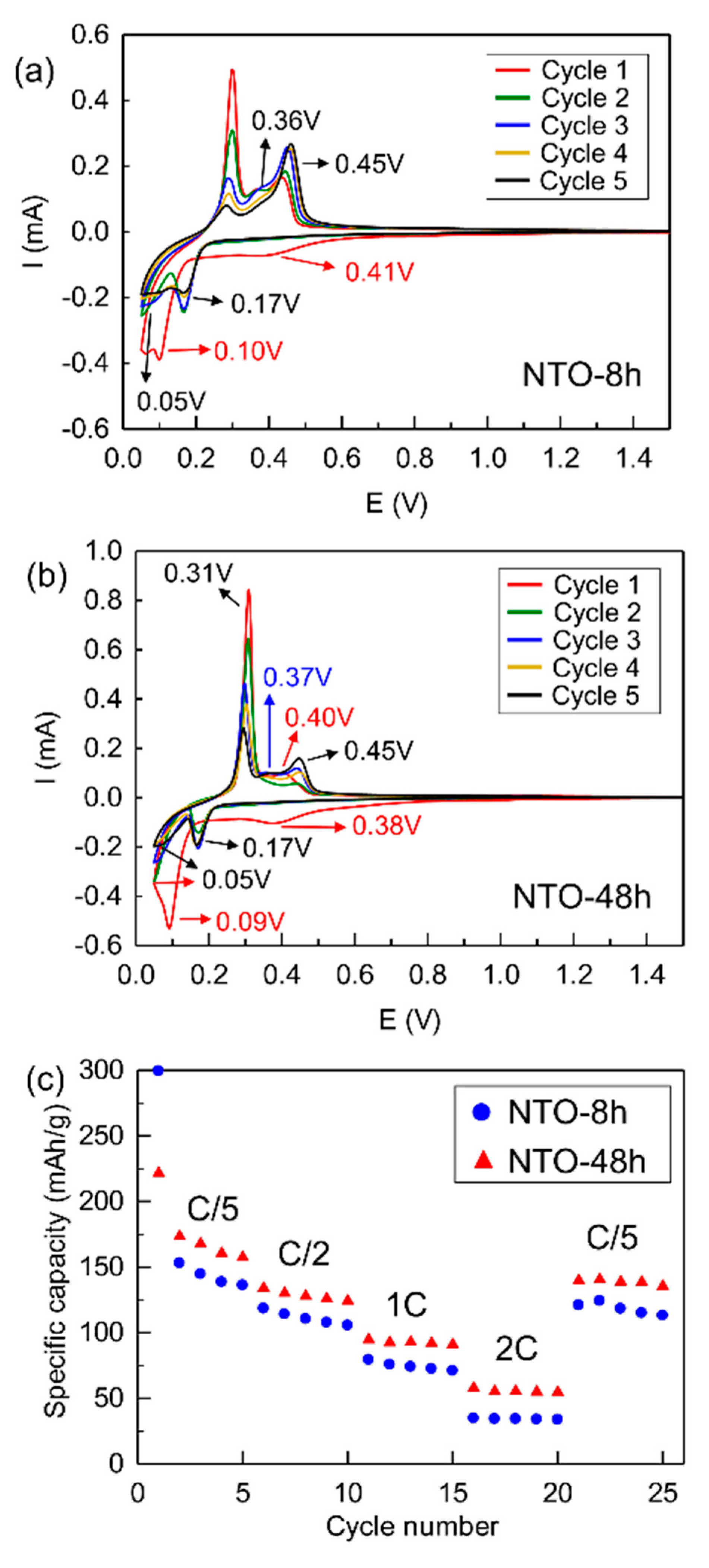

3.4.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

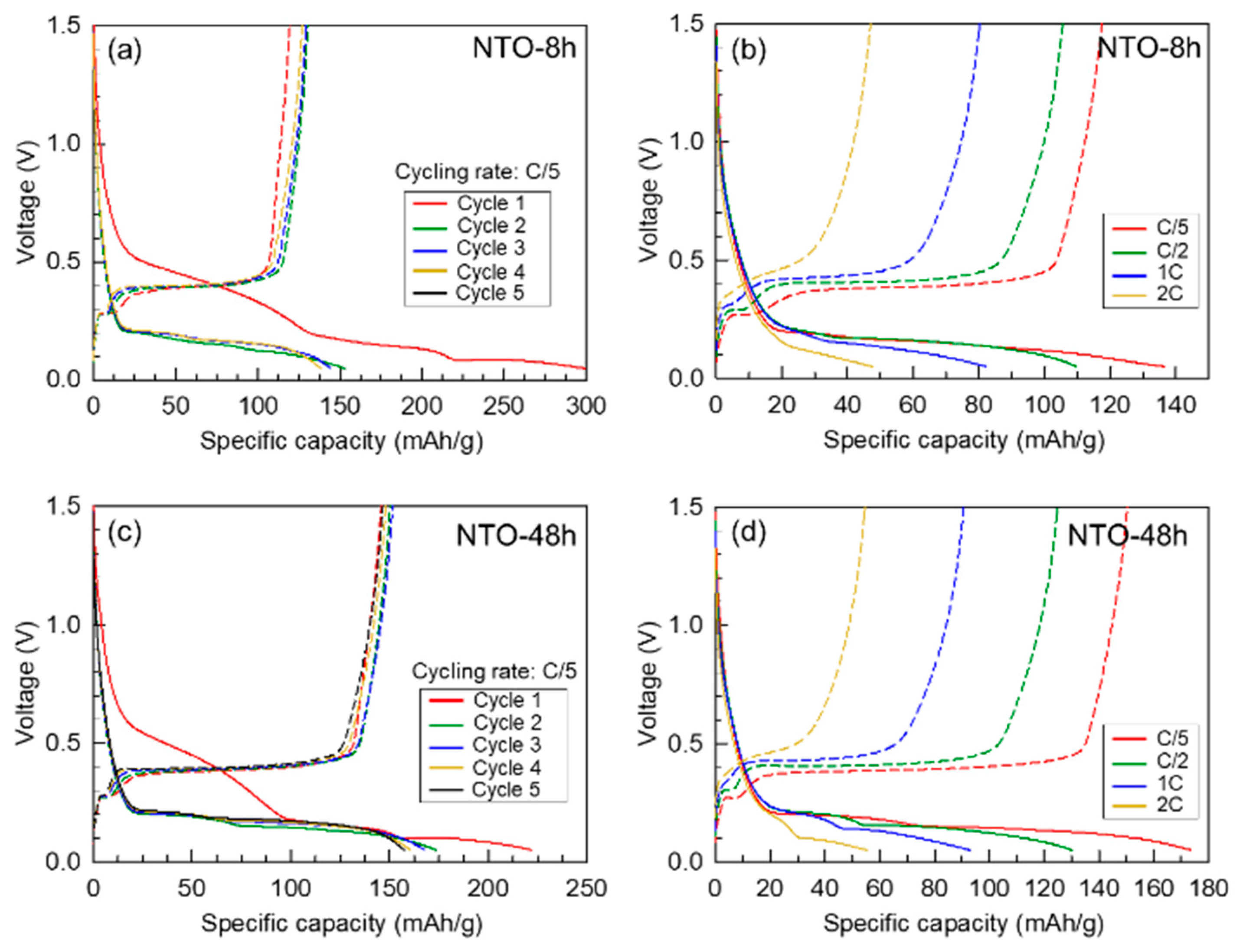

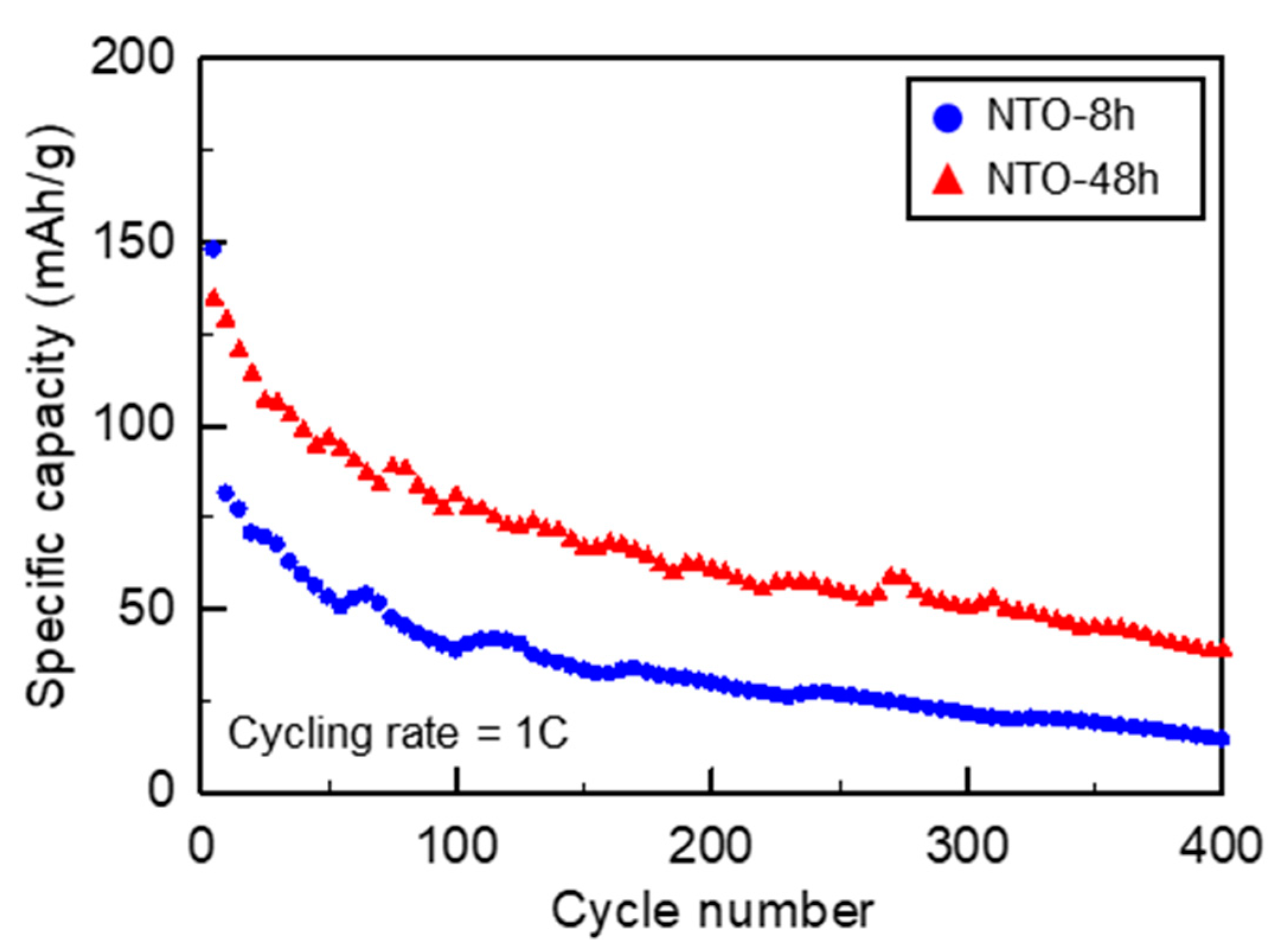

3.4.2. Galvanostatic Cycling

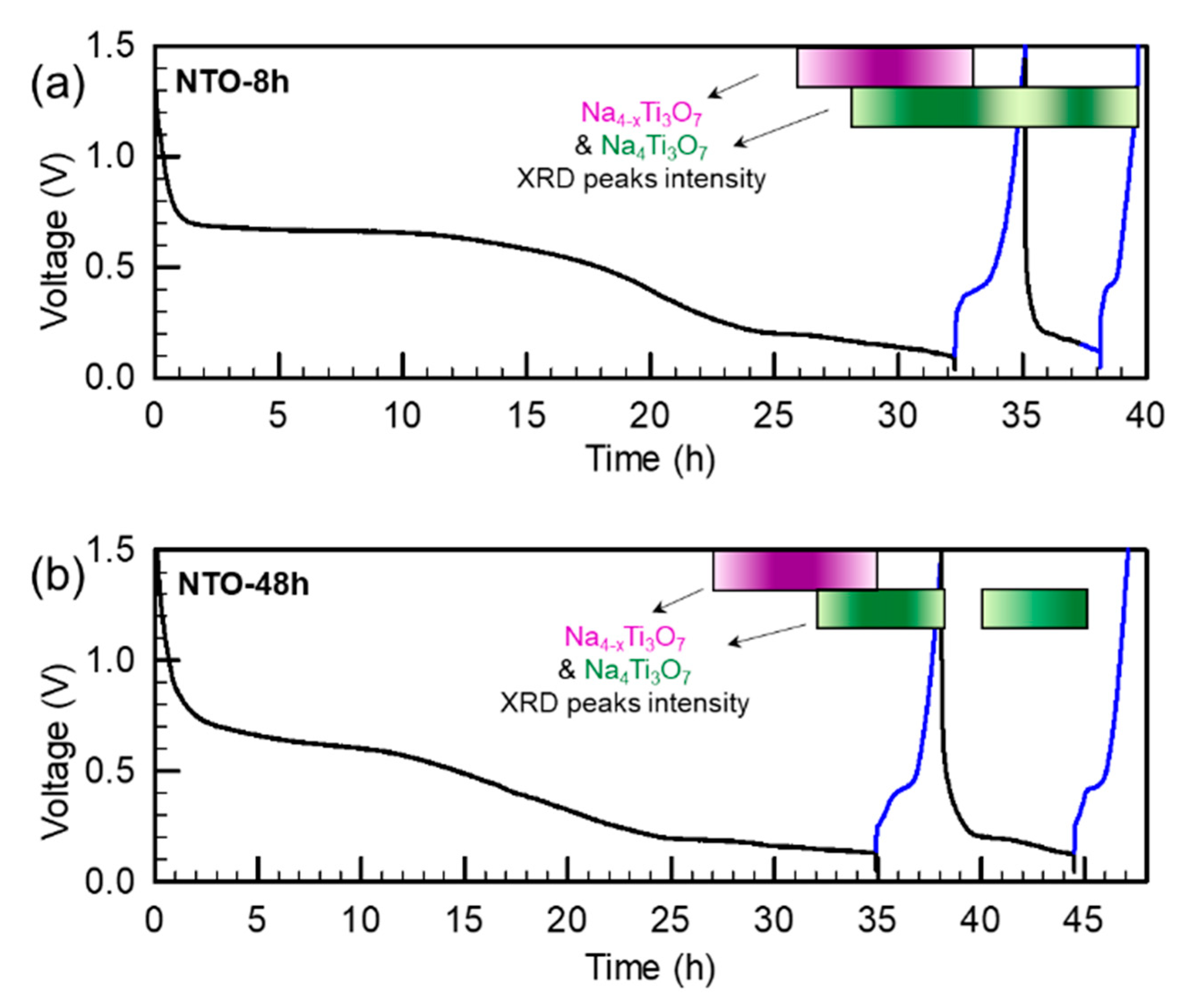

3.4.3. Study of the Reaction Mechanism by Operando XRD

3.4.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Studies

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Chayambuka, K.; Mulder, G.; Danilov, D.L.; Notten, P.H.L. Sodium-Ion Battery Materials and Electrochemical Properties Reviewed. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senguttuvan, P.; Rousse, G.; Seznec, V.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Palacín, M. Na2Ti3O7: Lowest Voltage Ever Reported Oxide Insertion Electrode for Sodium Ion Batteries. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 4109–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, T.; Siddiq, M.; Shahzad, N.; Ihsan, R.; Ahmad, A.; Shahzad, M.I. Prospects in anode materials for sodium ion batteries - A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 119, 109549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-Y.; Myung, S.-T.; Sun, Y.-K. Sodium-ion batteries: present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3529–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, I.; Mariyappan, S.; Saurel, D.; Adelhelm, P.; Koposov, A.Y.; Masquelier, C.; Croguennec, L.; Casas-Cabanas, M. Challenges of today for Na-based batteries of the future: From materials to cell metrics. J. Power Sources 2020, 482, 228872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, Z.; Hong, Z.; Titirici, M.-M. Ultrafast synthesis of hard carbon anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Rudola, A.; Balaya, P. Investigations of Thermal Stability and Solid Electrolyte Interphase on Na2Ti3O7/C as a Non-carbonaceous Anode Material for Sodium Storage Using Non-flammable Ether-based Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 11732–11740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Z.; Kang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhou, K.; Huang, Z.; Wei, M. Synthesis of Mesoporous Co2+-Doped TiO2 Nanodisks Derived from Metal Organic Frameworks with Improved Sodium Storage Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 32071–32079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, H.; Xia, B.Y.; Park, H.S. Ti-based electrode materials for electrochemical sodium ion storage and removal. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 22163–22188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhao, H.; Pang, W.K.; Yin, Z.; Zhou, B.; He, G.; Guo, Z.; Du, Y. Lanthanide doping induced electrochemical enhancement of Na2Ti3O7 anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3421–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava-Avendaño, J.; Morales-García, A.; Ponrouch, A.; Rousse, G.; Frontera, C.; Senguttuvan, P.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Dompablo, M.E.A.-D.; Palacín, M.R. Taking steps forward in understanding the electrochemical behavior of Na2Ti3O7. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 22280–22286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabeitia, M.; Nobili, F.; Muñoz-Márquez, M. .; Rojo, T.; Casas-Cabanas, M. Direct observation of electronic conductivity transitions and solid electrolyte interphase stability of Na2Ti3O7 electrodes for Na-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 330, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulova, T.L.; Kudryashova, Y.O.; Kuz’mina, A.A.; Skundin, A.M.; Stenina, I.A.; Chekannikov, A.A.; Yaroslavtsev, A.B.; Libich, J. Study of degradation of Na2Тi3O7-based electrode during cycling. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2018, 23, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yu, C.; Liu, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhu, H.; Jiao, S. Single crystalline Na2Ti3O7rods as an anode material for sodium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudola, A.; Saravanan, K.; Mason, C.W.; Balaya, P. Na2Ti3O7: an intercalation based anode for sodium-ion battery applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Yu, X.; Hu, Y.-S.; Li, H.; Yang, X.-Q.; Chen, L. Sodium Storage and Transport Properties in Layered Na2Ti3O7for Room-Temperature Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, C.; Balasubramanian, M.; Meng, Y.S. Understanding Na2Ti3O7 as an ultra-low voltage anode material for a Na-ion battery. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 12564–12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Li, J.; Deng, Q.; Xue, J.; Dai, X.; Zhou, A.; Li, J. Microspherical Na2Ti3O7 prepared by spray-drying method as anode material for sodium-ion battery. Solid State Ionics 2014, 262, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Ding, H.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, D.; Mao, L.; Li, S. Effects of sodium salts on compatibility between Na2Ti3O7@C anode and electrolyte for sodium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, C.; Luo, K.; Zhong, B.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.G.; Guo, X.-D. Enabling both ultrahigh initial coulombic efficiency and superior stability of Na2Ti3O7 anodes by optimizing binders. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 24178–24189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudola, A.; Sharma, N.; Balaya, P. Introducing a 0.2 V sodium-ion battery anode: The Na2Ti3O7 to Na3−xTi3O7 pathway. Electrochem. Commun. 2015, 61, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, S.; Kõrösi, L.; Meynen, V.; Cool, P.; Vansant, E.F.; Dékány, I. The influence of temperature on the structural behaviour of sodium tri- and hexa-titanates and their protonated forms. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, Y.-C.; Rim, C.-H.; Hwang, S.-G.; Ri, K.-C.; Yu, C.-J. Defect formation and ambivalent effects on electrochemical performance in layered sodium titanate Na2Ti3O7. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 3420–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-S.; Costa, S.I.R.; Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Scanlon, D.O. Intrinsic Defects and Their Role in the Phase Transition of Na-Ion Anode Na2Ti3O7. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 6, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ye, Q.; Wang, F.; Fan, X.; Hu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhai, T.; Li, H. A New Triclinic Phase Na2Ti3O7 Anode for Sodium-Ion Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piffet, C.; Vertruyen, B.; Hatert, F.; Cloots, R.; Boschini, F.; Mahmoud, A. High temperature X-ray diffraction study of the formation of Na2Ti3O7 from a mixture of sodium carbonate and titanium oxide. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 65, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.D.S.; da Silva, J.P.; Biondo, M.M.; Sanches, E.A.; Paula, M.M.D.S.; Nobre, F.X.; Rivera, J.A.; Zulueta, Y.A.; Torikachvili, M.S.; Sampaio, D.V.; et al. Temperature Dependence of the Electrical Properties of Na2Ti3O7/Na2Ti6O13/POMA Composites. Molecules 2022, 27, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubovich, O.V.; Kireev, V.V. Refinement of the crystal structure of Na2Ti3O7. Crystallogr. Rep. 2003, 48, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Llewellyn, P.; Rouquerol, F. Is the bet equation applicable to microporous adsorbents? Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2007, 160, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leriche, J.B.; Hamelet, S.; Shu, J.; Morcrette, M.; Masquelier, C.; Ouvrard, G.; Zerrouki, M.; Soudan, P.; Belin, S.; Elkaïm, E.; et al. An Electrochemical Cell for Operando Study of Lithium Batteries Using Synchrotron Radiation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A606–A610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Wadsley, A.D. The crystal structure of Na2Ti3O7. Acta Crystallogr. 1961, 14, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.D.; Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 1985, B41, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadois, C.; Światowska, J.; Zanna, S.; Marcus, P. Influence of Titanium Surface Treatment on Adsorption of Primary Amines. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 117, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, W.; Morgan, B.J.; Światowska, J.; Baddour-Hadjean, R.; Body, M.; Legein, C.; Borkiewicz, O.J.; Leclerc, S.; Groult, H.; et al. Lithium Intercalation in Anatase Titanium Vacancies and the Role of Local Anionic Environment. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 3078–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraz, S.; Luo, W.; Swiatowska, J.; Bezzazi, B.; Taleb, A. Hydrothermal Synthesis of TiO2 Aggregates and Their Application as Negative Electrodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: The Conflicting Effects of Specific Surface and Pore Size. Materials 2021, 14, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Ye, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.-G. Self-doping of Ti3+into Na2Ti3O7 increases both ion and electron conductivity as a high-performance anode material for sodium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2018, 767, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Márquez, M.A.; Zarrabeitia, M.; Castillo-Martínez, E.; Eguía-Barrio, A.; Rojo, T.; Casas-Cabanas, M. Composition and Evolution of the Solid-Electrolyte Interphase in Na2Ti3O7 Electrodes for Na-Ion Batteries: XPS and Auger Parameter Analysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 7801–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, D. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy C. D. Wanger, W. M. Riggs, L. E. Davis, J. F. Moulder and G. E.Muilenberg Perkin-Elmer Corp., Physical Electronics Division, Eden Prairie, Minnesota, USA, 1979. 190 pp. $195. Surf. Interface Anal. 1981, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.S.; Ramireddy, T.; Pradeep, A.; Jangid, M.K.; Srihari, V.; Poswal, H.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Understanding the Cyclic (In)stability and the Effects of Presence of a Stable Conducting Network on the Electrochemical Performances of Na2 Ti3 O7. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Das, D.; Banerjee, S.; Majumder, S.B. Synthesis and electrochemical performance of in-situ and ex-situ carbon- coated Na2Ti3O7, as a promising anode for sodium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulova, T.L.; Skundin, A.M. Balance between reversible and irreversible processes during lithium intercalation in graphite. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2006, 42, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.; Amarilla, J.M.; Lasri, K.; Saadoune, I. Influence of the synthesis method on the electrochemical properties of the Li4Ti5O12 spinel in Li-half and Li-ion full-cells. A systematic comparison. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 93, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschuk, N.O.; Easton, E.B.; Zenkina, O.V. Reducing the resistance for the use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis in materials chemistry. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27925–27936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, D. Negative capacitance or inductive loop? – A general assessment of a common low frequency impedance feature. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 98, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Deng, J.; Leow, W.R.; Xia, H.; Zhu, Z.; Lv, Z.; Wei, J.; Li, W.; Persson, C.; et al. Correlating the Peukert’s Constant with Phase Composition of Electrode Materials in Fast Lithiation Processes. ACS Mater. Lett. 2019, 1, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).