Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes, Chitosan Nanogels

2.3. Nanoparticles Obtaining and Characterization

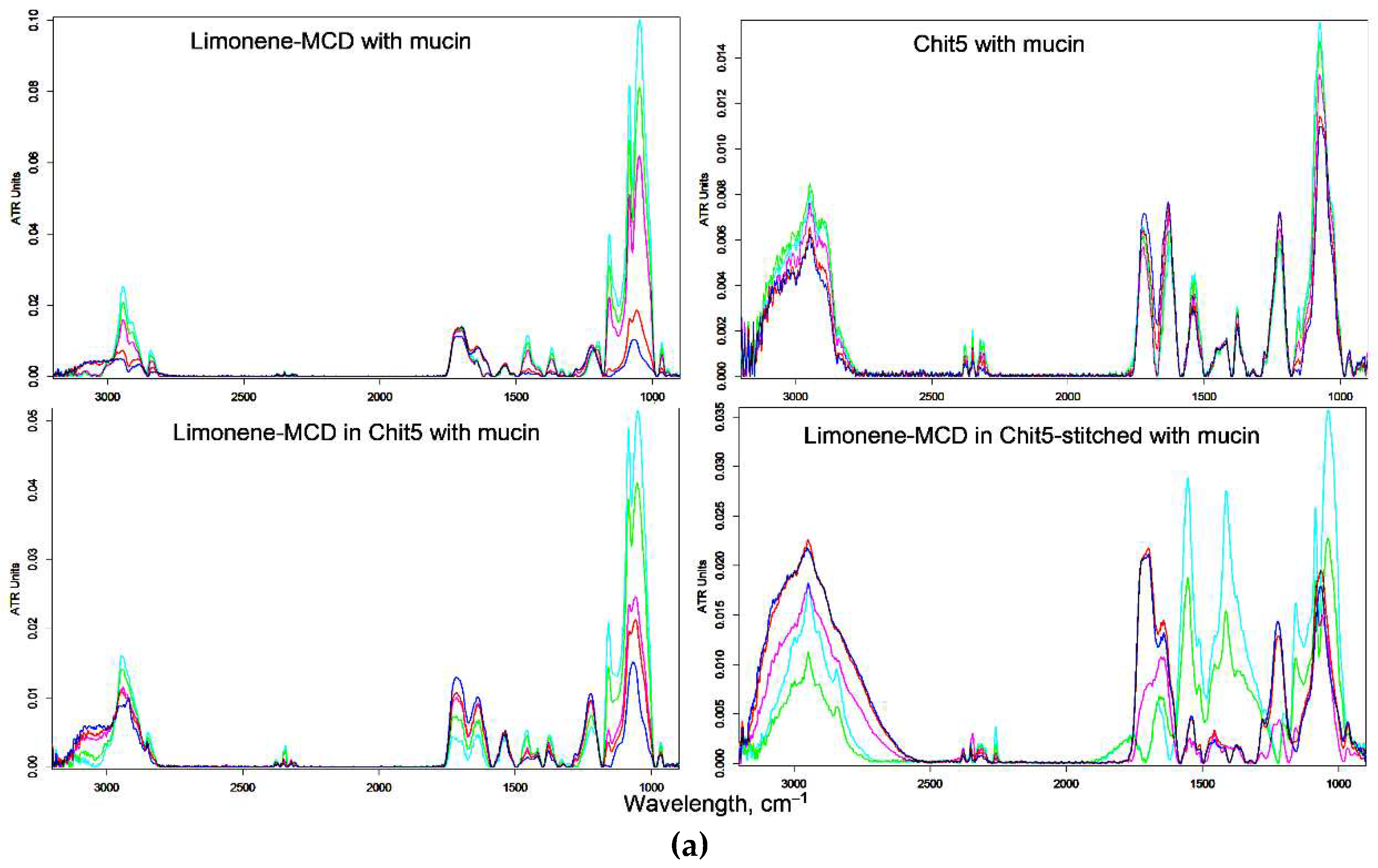

2.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

2.5. UV Spectroscopy

2.6. Drug Capacity of Nanogels

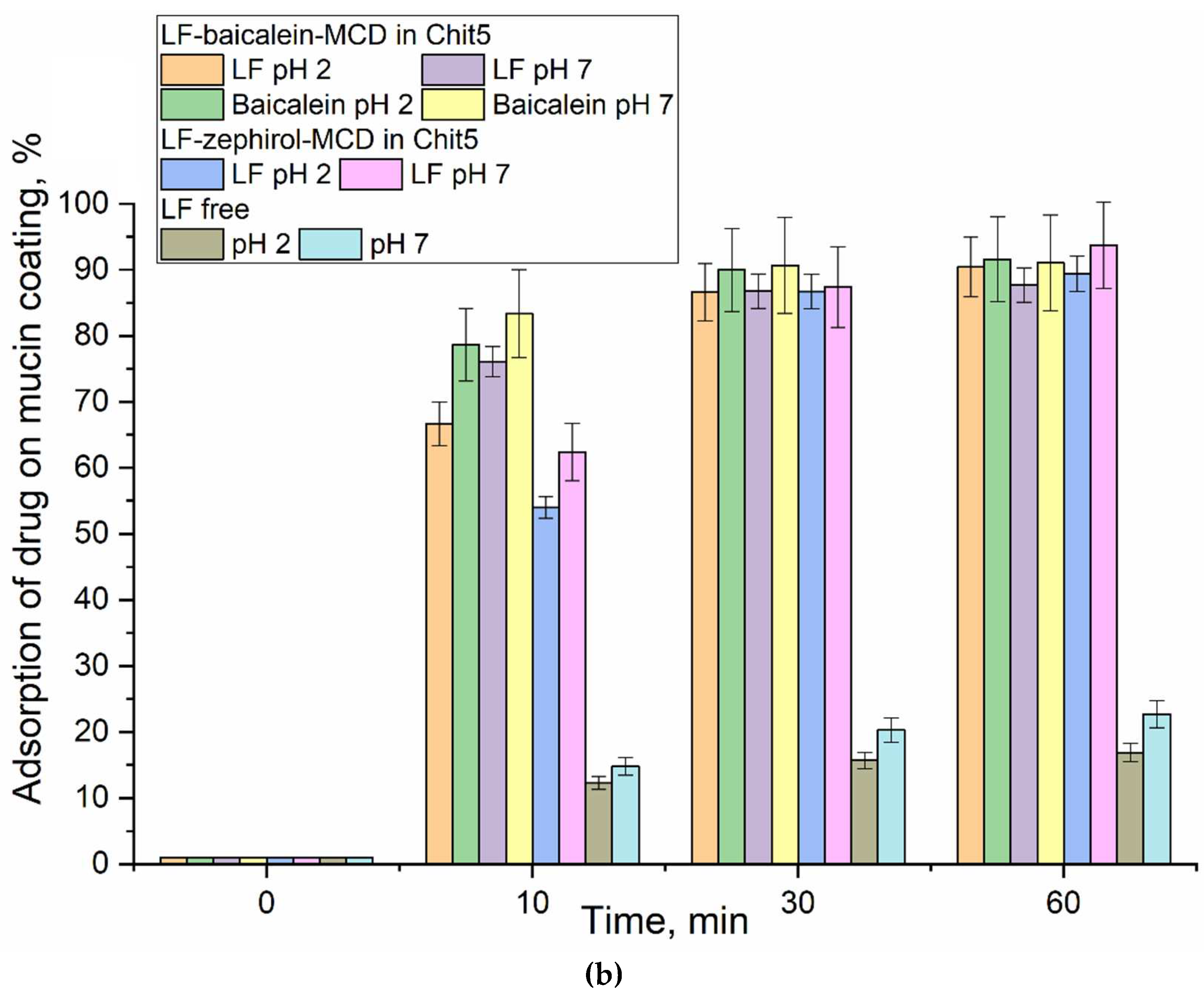

2.7. Study of the Mucoadhesive Properties of Nanogels

2.8. Antioxidant Activity Using ABTS Assay

2.9. Antibacterial Activity Studies: FTIR Spectroscopy, Microbiology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inclusion of Drugs in MCD and Chitosan Nanogels

3.2. Molecular Mechanism of Formation of Chitosan-Genipin Based Nanogels

3.3. Antibacterial Activity of Drugs in a Simple Form and in the Form of a Nanogel

3.3.1. Broad Activity Screening of Individual Components of Drug Formulations

3.3.2. Combined Formulations LF + Second Drug in Nanogel

3.3.3. Prolonged Effect of Selected Medicinal Formulations

3.3.4. FTIR Spectroscopy and Flow Cytometry for Studying of Mechanism of Drug Action on Cells

3.4. Antioxidant Activity of Components of Natural Extracts and Drugs in Chitosan Nanogel

3.5. Mucoadhesive Properties of Chitosan Nanoparticles

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | cyclodextrin |

| EG | eugenol |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| LF | levofloxacin |

| MCD | methyl-cyclodextrin |

| MM | miramistin |

| MN | metronidazole |

| SEC | selectivity coefficient |

| SHA | salicylhydroxamic acid |

| SYC | synergy coefficient |

References

- Parnmen, S.; Nooron, N.; Leudang, S.; Sikaphan, S.; Polputpisatkul, D.; Rangsiruji, A. Phylogenetic evidence revealed Cantharocybe virosa (Agaricales, Hygrophoraceae) as a new clinical record for gastrointestinal mushroom poisoning in Thailand. Toxicol. Res. 2020, 36, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoegberg, L.C.G.; Shepherd, G.; Wood, D.M.; Johnson, J.; Hoffman, R.S.; Caravati, E.M.; Chan, W.L.; Smith, S.W.; Olson, K.R.; Gosselin, S. Systematic review on the use of activated charcoal for gastrointestinal decontamination following acute oral overdose. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 1196–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, L.; Palsson, O.S.; Pandolfino, J.E. Best Practice Update: Incorporating Psychogastroenterology Into Management of Digestive Disorders. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, M.; Petraccia, L.; Mennuni, G.; Fontana, M.; Scarno, A.; Sabetta, S.; Fraioli, A. Cambios, dolencias funcionales y enfermedades en el sistema gastrointestinal en personas mayores. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalelkar, P.P.; Riddick, M.; García, A.J. Biomaterial-based antimicrobial therapies for the treatment of bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Ma, J.; Wei, B. Oral absorption and drug interaction kinetics of moxifloxacin in an animal model of weightlessness. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, W.; Lambert, J.R.; Dwyer, B. Cytotoxin production by Helicobacter pylori from patients with upper gastrointestinal tract diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 1203–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J. Review article: Bacteria and pathogenesis of disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract - Beyond the era of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 39, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilat, T.L.; Kuzmina, L.P.; Bezrukavnikova, L.M.; Kolyaskina, M.M.; Korosteleva, M.M.; Ismatullaeva, S.S.; Khanferyan, R.A. Dietary therapeutic and preventive food products in complex therapy of gastroinal tract diseases associated with helicobacter pylori. Meditsinskiy Sov. 2021, 2021, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Cong, H.; Hu, H.; Xu, F.J. An overview of chitosan and its application in infectious diseases. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.E.; Gomes, C.; Taylor, T.M. Characterization of beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes containing essential oils (trans-cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, cinnamon bark, and clove bud extracts) for antimicrobial delivery applications. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, N.N.R.; Alviano, C.S.; Blank, A.F.; Romanos, M.T. V.; Fonseca, B.B.; Rozental, S.; Rodrigues, I.A.; Alviano, D.S. Synergism Effect of the Essential Oil from Ocimum basilicum var. Maria Bonita and Its Major Components with Fluconazole and Its Influence on Ergosterol Biosynthesis. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M.; Yoshinari, T.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Rezaee, M.B.; Nagasawa, H.; Sakuda, S. Dillapiol and apiol as specific inhibitors of the biosynthesis of aflatoxin G1 in Aspergillus parasiticus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2329–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenov, V. V.; Rusak, V. V.; Chartov, E.M.; Zaretskii, M.I.; Konyushkin, L.D.; Firgang, S.I.; Chizhov, A.O.; Elkin, V. V.; Latin, N.N.; Bonashek, V.M.; и др. Polyalkoxybenzenes from plant raw materials 1. Isolation of polyalkoxybenzenes from CO2 extracts of Umbelliferae plant seeds. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2007, 56, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E. V Spectroscopy Approach for Highly - Efficient Screening of Lectin - Ligand Interactions in Application for Mannose Receptor and Molecular Containers for Antibacterial Drugs. 2022.

- Leite, A.M.; Lima, E.D.O.; De Souza, E.L.; Diniz, M.D.F.F.M.; Trajano, V.N.; De Medeiros, I.A. Inhibitory effect of β-pinene, α-pinene and eugenol on the growth of potential infectious endocarditis causing Gram-positive bacteria. Rev. Bras. Ciencias Farm. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 43, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Petrov, R.A.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V. Mannosylated Polymeric Ligands for Targeted Delivery of Antibacterials and Their Adjuvants to Macrophages for the Enhancement of the Drug Efficiency. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Belogurova, N.G.; Krylov, S.S.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V; Kudryashova, E. V Plant Alkylbenzenes and Terpenoids in the Form of Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes as Antibacterial Agents and Levofloxacin Synergists. 2022.

- Valdivieso-Ugarte, M.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Gil, Á. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties of essential oils: A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boire, N.A.; Riedel, S.; Parrish, N.M. Essential Oils and Future Antibiotics: New Weapons against Emerging’Superbugs’? Journal of Ancient Diseases & Preventive Remedies. J Anc Dis Prev Rem 2013, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, A. V.; Shevchenko, O.G.; Rusak, V. V.; Chartov, E.M.; Myshlyavtsev, A.B.; Rusanov, D.A.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V. Antioxidant Activity of Natural Allylpolyalkoxybenzene Plant Essential Oil Constituents. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, C. Bin; Han, K.T.; Cho, K.S.; Ha, J.; Park, H.J.; Nam, J.H.; Kil, U.H.; Lee, K.T. Eugenol isolated from the essential oil of Eugenia caryophyllata induces a reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 2005, 225, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadtong, S.; Watthanachaiyingcharoen, R.; Kamkaen, N. Antimicrobial constituents and synergism effect of the essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus and Alpinia galanga. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, A.M.; Silva-Silva, J.V.; Fernandes, J.M.P.; Abreu-Silva, A.L.; Calabrese, K.D.S.; Mendes Filho, N.E.; Mouchrek, A.N.; Almeida-Souza, F. GC-MS Characterization of Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Antitrypanosomal Activity of Syzygium aromaticum Essential Oil and Eugenol. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana-Sánchez, A.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M.; Obledo-Vázquez, E.N.; Padilla-Camberos, E.; Silva-Vázquez, R.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Mexican oregano essential oils (Lippia graveolens H. B. K.) with different composition when microencapsulated inβ-cyclodextrin. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.; Tambor, K.; Herman, A. Linalool Affects the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Essential Oils. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 72, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Davydova, M.P.; Danilov, M.R.; Dyachkova, U.D.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Kudryashova, E. V Mannosylated Systems for Targeted Delivery of Antibacterial Drugs to Activated Macrophages. 2022, 1–29.

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyasov, I.R.; Beloborodov, V.L.; Selivanova, I.A.; Terekhov, R.P. ABTS/PP decolorization assay of antioxidant capacity reaction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białas, N.; Sokolova, V.; van der Meer, S.B.; Knuschke, T.; Ruks, T.; Klein, K.; Westendorf, A.M.; Epple, M. Bacteria ( E. coli ) take up ultrasmall gold nanoparticles (2 nm) as shown by different optical microscopic techniques (CLSM, SIM, STORM). Nano Sel. 2022, 3, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Jin, M.; Vu, S.H.; Jung, S.; He, N.; Zheng, Z.; Lee, M.S. Application of chitosan/alginate nanoparticle in oral drug delivery systems: prospects and challenges. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Gupta, S.; Singh, A.R.; Ferosekhan, S.; Kothari, D.C.; Pal, A.K.; Jadhao, S.B. Chitosan Nanoencapsulated Exogenous Trypsin Biomimics Zymogen-Like Enzyme in Fish Gastrointestinal Tract. PLoS One 2013, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Sirvi, A.; Kaur, S.; Samal, S.K.; Roy, S.; Sangamwar, A.T. Polymeric micelles based on amphiphilic oleic acid modified carboxymethyl chitosan for oral drug delivery of bcs class iv compound: Intestinal permeability and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 153, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Araújo, M.; Novoa-Carballal, R.; Andrade, F.; Gonçalves, H.; Reis, R.L.; Lúcio, M.; Schwartz, S.; Sarmento, B. Novel amphiphilic chitosan micelles as carriers for hydrophobic anticancer drugs. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranachai, T.; Praphairaksit, N.; Muangsin, N. Chitosan/polyethylene glycol beads crosslinked with tripolyphosphate and glutaraldehyde for gastrointestinal drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Zhai, G. The design of pH-sensitive chitosan-based formulations for gastrointestinal delivery. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Streltsov, D.A.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V. Chitosan or Cyclodextrin Grafted with Oleic Acid Self-Assemble into Stabilized Polymeric Micelles with Potential of Drug Carriers. Life 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindén, S.; Mahdavi, J.; Hedenbro, J.; Borén, T.; Carlstedt, I. Effects of pH on Helicobacter pylori binding to human gastric mucins: Identification of binding to non-MUC5AC mucins. Biochem. J. 2004, 384, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.P. Colonization and infection by Helicobacter pylori in humans. Helicobacter 2007, 12, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchicchi, B.; Hensel, A.; Goycoolea, F. Polysaccharides as Bacterial Antiadhesive Agents and “Smart” Constituents for Improved Drug Delivery Systems Against Helicobacter pylori Infection. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 4888–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.J.; Guo, R.T.; Lu, I.L.; Liu, H.G.; Wu, S.Y.; Ko, T.P.; Wang, A.H.J.; Liang, P.H. Structure-based inhibitors exhibit differential activities against Helicobacter pylori and Escherichia coli undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthases. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2008, 2008, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Caro, S.; Zocco, M.A.; Cremonini, F.; Candelli, M.; Nista, E.C.; Bartolozzi, F.; Armuzzi, A.; Cammarota, G.; Santarelli, L.; Gasbarrini, A. Levofloxacin based regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002, 14, 1309–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Caro, S.; Fini, L.; Daoud, Y.; Grizzi, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; De Lorenzo, A.; Di Renzo, L.; McCartney, S.; Bloom, S. Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based schemes vs quadruple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in second-line. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 5669–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Savchenko, I. V; Kudryashova, E. V Fluorescent Probes with Förster Resonance Energy Transfer Function for Monitoring the Gelation and Formation of Nanoparticles Based on Chitosan Copolymers. 2023.

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Streltsov, D.A.; Ezhov, A.A. Smart pH- and Temperature-Sensitive Micelles Based on Chitosan Grafted with Fatty Acids to Increase the Efficiency and Selectivity of Doxorubicin and Its Adjuvant Regarding the Tumor Cells. 2023.

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Dyachkova, U.D.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V Application Prospects of FTIR Spectroscopy and CLSM to Monitor the Drugs Interaction with Bacteria Cells Localized in Macrophages for Diagnosis and Treatment Control of Respiratory Diseases. 2023, 1–23.

- Dawidowicz, A.L.; Olszowy, M. Does antioxidant properties of the main component of essential oil reflect its antioxidant properties? The comparison of antioxidant properties of essential oils and their main components. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1952–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, M.; Xiao, C.; Zhao, Q.; Su, G. Practical problems when using ABTS assay to assess the radical-scavenging activity of peptides: Importance of controlling reaction pH and time. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayaci, F.; Ertas, Y.; Uyar, T. Enhanced thermal stability of eugenol by cyclodextrin inclusion complex encapsulated in electrospun polymeric nanofibers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 8156–8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelić, R.; Tomović, M.; Stojanović, S.; Joksović, L.; Jakovljević, I.; Djurdjević, P. Study of inclusion complex of β-cyclodextrin and levofloxacin and its effect on the solution equilibria between gadolinium(III) ion and levofloxacin. Monatshefte fur Chemie 2015, 146, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, T.; Chen, F.; Duan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y. An inclusion complex of eugenol into β-cyclodextrin: Preparation, and physicochemical and antifungal characterization. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, M.; Zha, B.; Diao, G. Correlation of polymer-like solution behaviors with electrospun fiber formation of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and the adsorption study on the fiber. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 9729–9737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miranda, J.C.; Martins, T.E.A.; Veiga, F.; Ferraz, H.G. Cyclodextrins and ternary complexes: Technology to improve solubility of poorly soluble drugs. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 47, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, A.; Ringard-lefebvre, C.; Baszkin, A. Drug – Cyclodextrin Association Constants Determined by Surface Tension and Surface Pressure Measurements. 1999, 285, 280–285.

- Szabó, Z.I.; Deme, R.; Mucsi, Z.; Rusu, A.; Mare, A.D.; Fiser, B.; Toma, F.; Sipos, E.; Tóth, G. Equilibrium, structural and antibacterial characterization of moxifloxacin-β-cyclodextrin complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1166, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kemary, M.; Sobhy, S.; El-Daly, S.; Abdel-Shafi, A. Inclusion of Paracetamol into β-cyclodextrin nanocavities in solution and in the solid state. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 79, 1904–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfoury, M.; Landy, D.; Auezova, L.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S. Effect of cyclodextrin complexation on phenylpropanoids’ solubility and antioxidant activity. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2322–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szente, L.; Singhal, A.; Domokos, A.; Song, B. Cyclodextrins: Assessing the impact of cavity size, occupancy, and substitutions on cytotoxicity and cholesterol homeostasis. Molecules 2018, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarzycki, P.K.; Lamparczyk, H. The equilibrium constant of β-cyclodextrin-phenolphtalein complex; Influence of temperature and tetrahydrofuran addition. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1998, 18, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Malashkeevich, S.M.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V. Thermoreversible Gels Based on Chitosan Copolymers as “Intelligent” Drug Delivery System with Prolonged Action for Intramuscular Injection. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Ferberg, A.S.; Krylov, S.S.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V; Kudryashova, E. V Polymeric Micelles Formulation of Combretastatin Derivatives with Enhanced Solubility, Cytostatic Activity and Selectivity against Cancer Cells. 2023.

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Dobryakova, N. V; Ezhov, A.A.; Kudryashova, E. V Achievement of the selectivity of cytotoxic agents against can- cer cells by creation of combined formulation with terpenoid adjuvants as prospects to overcome multidrug resistance. 2022, 1–34.

- Elshafie, H.S.; Sakr, S.H.; Sadeek, S.A.; Camele, I. Biological Investigations and Spectroscopic Studies of New Moxifloxacin/Glycine-Metal Complexes. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E. V. Mannose Receptors of Alveolar Macrophages as a Target for the Addressed Delivery of Medicines to the Lungs. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 48, 46–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| in MCD | in MCD-Chit5 | in MCD-Chit5-gen | |||||||

| 1 mg/mL | 0.1 mg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 1 mg/mL | 0.1 mg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 1 mg/mL | 0.1 mg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | |

| Linalool | 78±6 | 85±8 | 0.6±0.1 | 73±4 | 82±5 | 0.20±0.05 | 58±3 | 76±7 | 0.30±0.06 |

| Menthol | 83±6 | 90±4 | 1.1±0.1 | 81±5 | 90±3 | 0.4±0.1 | 79±6 | 84±5 | 0.4±0.1 |

| Zephirol | 12±2 | 34±3 | 0.8±0.1 | 10±1 | 33±2 | 1.2±0.2 | 10±1 | 23±2 | 1.6±0.2 |

| Quercetin | 85±5 | 92±4 | 1.1±0.1 | 87±4 | 92±3 | 0.9±0.1 | 82±6 | 89±5 | 0.9±0.1 |

| Dihydroquercetin | 86±3 | 91±4 | 1.1±0.1 | 87±5 | 95±2 | 1.0±0.1 | 83±4 | 87±6 | 0.24±0.02 |

| Eugenol | 79±3 | 90±4 | 0.9±0.1 | 70±2 | 85±3 | 1.1±0.1 | 67±5 | 82±4 | 1.2±0.1 |

| Baicalein | 26±3 | 72±7 | 1.8±0.2 | 49±4 | 68±6 | 1.6±0.2 | 66±3 | 77±5 | 0.8±0.1 |

| Myristicin | 80±5 | 87±5 | 1.0±0.1 | 86±4 | 86±7 | 1.2±0.1 | 90±2 | 89±3 | 1.0±0.1 |

| Limonene | 83±4 | 90±2 | 1.0±0.1 | 87±3 | 88±5 | 1.0±0.1 | 87±6 | 89±4 | 0.9±0.1 |

| Azaron | 81±5 | 87±4 | 0.7±0.1 | 86±6 | 91±3 | 0.8±0.1 | 64±3 | 87±2 | 1.0±0.2 |

| 1 μg/mL | 0.1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 1 μg/mL | 0.1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 1 μg/mL | 0.1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | |

| LF | 9±1 | 16±3 | 2.3±0.2 | 7±1 | 14±2 | 3.6±0.3 | 7±1 | 13±3 | 4.0±0.3 |

| 10 μg/mL | 1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 10 μg/mL | 1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | 10 μg/mL | 1 μg/mL | Selectivity (E. coli vs Lactobacillus) | |

| MN | 41±4 | 77±5 | 0.8±0.1 | 46±7 | 82±8 | 0.7±0.1 | 20±2 | 69±3 | 1.4±0.1 |

| MM | 10±2 | 26±4 | 0.7±0.1 | 9±1 | 18±3 | 2.3±0.3 | 10±1 | 15±1 | 2.4±0.1 |

| SHA | 20±3 | 84±5 | 0.5±0.1 | 20±2 | 85±3 | 0.6±0.1 | 17±2 | 76±8 | 0.7±0.1 |

| Compound X | Linalool | Menthol | Zephirol | Quercetin | Dihydroquercetin | Eugenol | Baicalein | Myristicin | Limonene | Azaron | MN | MM | SHA |

| E. coli | 1.06±0.13 | 1.49±0.20 | 1.14±0.05 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.3±0.2 | 1.16±0.07 | 1.15±0.05 | 1.08±0.09 | 1.27±0.08 | 1.0±0.1 | 0.23±0.02 | 1.23±0.05 | 1.73±0.24 |

| Lactobacillus | 0.76±0.03 | 1.11±0.05 | 0.26±0.02 | 1.15±0.06 | 1.06±0.08 | 0.91±0.05 | 0.83±0.03 | 1.24±0.12 | 1.02±0.06 | 0.91±0.09 | 0.69±0.05 | 1.06±0.07 | 0.91±0.08 |

| Selectivity E. coli vs Lactobacillus | 1.4±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 | 4.4±0.4 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.4±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | 0.33±0.04 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.9±0.2 |

| Compound | IC50, mg/mL |

| Linalool | 0.46±0.07 |

| Menthol | >3 |

| Zephirol | 0.27±0.05 |

| Quercetin | <0.01 |

| Dihydroquercetin | |

| Eugenol | |

| Baicalein | |

| Myristicin | |

| Limonene | 1.5±0.2 |

| Azaron | ~0.01 |

| LF | 0.015±0.005 |

| MN | 0.04±0.01 |

| MM | 0.008±0.002 |

| SHA | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).