1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a change in the functioning of public administration. Imposed social isolation has resulted in increased demand for public e-services, allowing government customers to remotely handle matters important to them. The increased interest in using public e-services has led local government entities to increase the number of available e-services.

According to the current Polish legislation, public entities should make content and services available online while maintaining digital accessibility requirements. The indicator of such accessibility is their compliance with the WCAG 2.1 standard. It seems reasonable to examine whether the content and services made available by local governments generally meet the standards of digital accessibility, and if not, why not.

Within the study, the authors adopted the definition of digital accessibility in accordance with EN 301 549 V3.2.1 (2021-03) HARMONISED EUROPEAN STANDARD Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services: Digital accessibility is the extent to which digital products, systems, services, environments, and objects can be used by the biggest possible portion of the population, in the widest possible range of features and capabilities, in order to achieve the purpose for which the specified products, systems, services, environments, and objects have been produced and made available [Standard EN301549].

The research was carried out in two areas: the digital accessibility of the main informational websites of cities with county rights (physical survey) and the extent and manner of implementation of the obligation to ensure digital accessibility of LGUs (survey).

2. The Issue of Digital Accessibility in Polish Law

The issue of digital accessibility, although not yet explicitly named, was introduced into the Polish legal order by the Act of February 17, 2005, on informatization of the activities of entities performing public tasks [KRI Act]. The implementing provision of the Act was the Ordinance of the Council of Ministers of April 12, 2012, on the National Interoperability Framework, minimum requirements for public registers and information exchange in electronic form and minimum requirements for ICT systems [KRI Ordinance], which imposed on public entities the use of the WCAG 2.0 standard for all websites and applications they produce and make available.

The provision that directly introduced the concept of digital accessibility into Polish law is the Act of April 4, 2019, on digital accessibility of internet websites and mobile applications of public entities [Act 04/04/2019], which implements the DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL (EU) 2016/2102 of October 26, 2016, on the accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies [EU Directive 2016/2102].

The provisions of Law 04/04/2019 imposed the following obligations on Polish public entities:

1. Ensuring reliability: Public offices have been required to ensure that their websites and mobile applications can be used by people with disabilities. Websites and mobile applications must be designed, made accessible, and operated following the requirements outlined in the Act.

2. Monitoring and reporting: Offices must monitor the accessibility of their websites and mobile applications (accessibility declaration), and report on activities undertaken to ensure that the standards are maintained. These reports must be updated on a regular basis and made available to the public.

3. Training and services: Offices are required to provide their employees with the necessary training on developing and making websites and mobile applications digitally accessible. Employees should also be re-trained in the principles and techniques of creating their content.

4. Providing access information: Offices are required to make available information about the digital accessibility of their websites and applications, such as an accessibility declaration and contact information for users who need assistance with the digital accessibility of shared content.

5. Mutual recognition: If an office uses content provided by other sub-entities, it is obliged to check whether that content is accessible. If the content is not digitally accessible, the office should bring it up to accessibility standards or withdraw it from publication.

6. Accessibility of content procured from third parties: If the authority outsources the creation of an internet website or mobile application to an external company, it should include accessibility rules in the order/contract and monitor whether the content complies with the standards.

Another law introducing digital accessibility requirements is the Act of July 19, 2019, on Ensuring Accessibility for People with Special Needs [Law 19/07/2019]. The purpose of this law is to ensure equal access to various areas of social life, including information, services, buildings, and public spaces regardless of health condition or disability. The law thus expands the scope of accessibility to include architectural and communication accessibility. Concerning the use of information and communication technologies, this means the necessity of:

1. installation of devices or other technical means to serve the hearing-impaired, in particular, induction loops, FM systems, or devices based on other technologies aimed at assisting hearing,

2. providing information about the scope of activities on the website of the entity in question - in the form of an electronic file containing machine-readable text, recordings of content in Polish sign language, and information in easy-to-read text

3. providing, at the request of a person with special needs, communication with the public entity in the form specified in the request.

In addition, Law 19/07/2019 mandates public entities to appoint an accessibility officer and specifies the manner and scope of accessibility control in public entities, the manner of its certification, and penalties for evading the obligation to ensure accessibility.

The 10/07/2019 law implements the DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND COUNCIL (EU) 2019/882 of April 17, 2019, [EU Directive 2019/822] on the accessibility requirements for products and services

Analysing the timing and subject matter scope of the digital accessibility regulations implemented in Poland, it was to be expected that public administration would be prepared to provide digitally accessible electronic services when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out.

3. Survey of the LGUs’ Accessibility Level

3.1. Survey Assumptions

Informational websites of all 66 Polish cities with the status of “cities with county rights” were selected as the subjects of the study. This assumption is due to formal and practical reasons.

Formally, cities with county rights:

are the largest cities in Poland,

due to the distribution of population, they are the centres with the highest population of people at risk of digital exclusion (requiring digital accessibility),

due to the level of employment in city offices and the size of their budgets, they have the greatest human and financial potential to implement changes in the ICT area,

they are the main centres serving tourist traffic and foreign investment, and therefore their websites should be a model not only aesthetically and functionally, but also technologically.

The practical advantage of this particular research sample is the possibility to compare the results obtained with the results of the study of compliance with the WCAG standard conducted in 2015 after the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of April 12, 2012, on the National Interoperability Framework, minimum requirements for public registers and exchange of information in electronic form and minimum requirements for ICT systems entered into force.

3.2. Scope of the Study of the Websites

Web accessibility was checked on two levels:

Technical accessibility - ensures that people using screen readers (e.g., the blind or deaf-blind) can efficiently navigate the site and read the content provided. This level of accessibility is required in compliance with the WCAG standard.

Visual accessibility - the ability to use text magnification, change contrasts, invert colours, highlight active links in the text, and other facilitations in the “visual” use of web pages.

Both studies (2015 and 2023) checked compliance with the WCAG 2.0 standard by assuming that the WCAG 2.1 version of the standard includes the WCAG 2.0 standard, i.e., pages that do not meet the requirements of WCAG 2.0 certainly do not meet the requirements of version 2.1.

Table 1.

List of websites included in the study.

Table 1.

List of websites included in the study.

| City |

LGU website |

| Biała Podlaska |

https://bialapodlaska.pl/ |

| Białystok |

https://www.bialystok.pl/ |

| Bielsko-Biała |

https://bielsko-biala.pl/ |

| Bydgoszcz |

https://www.bydgoszcz.pl/ |

| Bytom |

https://www.bytom.pl/ |

| Chełm |

https://samorzad.gov.pl/web/miasto-chelm |

| Chorzów |

https://www.chorzow.eu/ |

| Częstochowa |

https://www.czestochowa.pl/ |

| Dąbrowa Górnicza |

https://www.dabrowa-gornicza.pl/ |

| Elbląg |

https://www.elblag.pl/ |

| Gdańsk |

https://www.gdansk.pl/ |

| Gdynia |

https://www.gdynia.pl/ |

| Gliwice |

https://gliwice.eu/ |

| Gorzów Wielkopolski |

https://um.gorzow.pl/ |

| Grudziądz |

https://grudziadz.pl/ |

| Jastrzębie-Zdrój |

https://www.jastrzebie.pl/ |

| Jaworzno |

https://www.jaworzno.pl/ |

| Jelenia Góra |

https://www.jeleniagora.pl/ |

| Kalisz |

https://www.kalisz.pl/ |

| Katowice |

https://katowice.eu/ |

| Kielce |

https://www.kielce.eu/ |

| Konin |

https://www.konin.pl/ |

| Koszalin |

https://www.koszalin.pl/ |

| Kraków |

https://www.krakow.pl/ |

| Krosno |

https://www.krosno.pl/ |

| Legnica |

https://portal.legnica.eu/ |

| Leszno |

https://leszno.pl/ |

| Lublin |

https://lublin.eu/ |

| Łomża |

http://www.lomza.pl/ |

| Łódź |

https://uml.lodz.pl/index.php |

| Mysłowice |

https://www.myslowice.pl/ |

| Nowy Sącz |

https://nowysacz.pl/ |

| Olsztyn |

https://olsztyn.eu/o-olsztynie.html |

| Opole |

https://www.opole.pl/dla-mieszkanca |

| Ostrołęka |

https://www.ostroleka.pl/ |

| Piekary Śląskie |

https://piekary.pl/ |

| Piotrków Trybunalski |

https://www.piotrkow.pl/ |

| Płock |

https://nowy.plock.eu/ |

| Poznań |

https://www.poznan.pl/ |

| Przemyśl |

https://przemysl.pl/ |

| Radom |

http://www.radom.pl/page/ |

| Ruda Śląska |

https://www.rudaslaska.pl/ |

| Rybnik |

https://www.rybnik.eu/ |

| Rzeszów |

https://www.erzeszow.pl/ |

| Siedlce |

https://siedlce.pl/ |

| Siemianowice Śląskie |

https://siemianowice.pl/ |

| Skierniewice |

https://www.skierniewice.eu/ |

| Słupsk |

https://www.slupsk.pl/ |

| Sopot |

https://www.sopot.pl/ |

| Sosnowiec |

https://www.sosnowiec.pl/ |

| Suwałki |

https://um.suwalki.pl/ |

| Szczecin |

https://www.szczecin.eu/pl |

| Świętochłowice |

https://swietochlowice.pl/ |

| Świnoujście |

https://www.swinoujscie.pl/ |

| Tarnobrzeg |

https://um.tarnobrzeg.pl/ |

| Tarnów |

https://www.tarnow.pl/ |

| Toruń |

https://www.torun.pl/ |

| Tychy |

https://umtychy.pl/ |

| Wałbrzych |

https://um.walbrzych.pl/ |

| Warszawa |

https://um.warszawa.pl/ |

| Włocławek |

https://www.wloclawek.eu/ |

| Wrocław |

https://www.wroclaw.pl/ |

| Zabrze |

https://miastozabrze.pl/ |

| Zamość |

http://www.zamosc.pl/ |

| Zielona Góra |

https://www.zielona-gora.pl/ |

| Żory |

https://www.zory.pl/ |

The following parameters were checked in the visual accessibility study for each site:

Publication of accessibility statements,

Responsiveness of the site

Ability to change text size,

Ability to change contrast,

Availability of a visual facilitation package (including at least: font size, contrast, highlighting active links, highlighting titles)

3.3. LGU Digital Accessibility Survey Study

The survey was conducted in two parts in December 2022 and March 2023 in the form of a standardized questionnaire sent to the local government units’ official email addresses. In the December 2022 survey, 97 LGUs responded, and in the March 2023 survey, another 156 LGUs responded. Since the responses of 3 LGUs were included in both surveys, those from March 2023 were included in the sample. A total of 250 LGUs responded to the accessibility questions, which makes 8.7% of the 2,873 LGUs in Poland.

In terms of digital accessibility, the questionnaires included the following questions:

1. Has your office made the accessibility declaration available on its website?

2. Has your office appointed an accessibility officer?

3. Are issues related to ensuring accessibility included in your office’s organizational documents?

4. Have all employees of your office received training on ensuring digital accessibility?

5. What organizational forms of training on digital accessibility have been used by your employees (please indicate the most popular)?

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Selected Websites of LGUs

A summary of the results obtained from the validation of selected websites for compliance with the WCAG 2.0 standard is presented in the table below:

Table 2.

Validation of the WCAG 2.0 standard for selected websites.

Table 2.

Validation of the WCAG 2.0 standard for selected websites.

| Number of errors in the code of the tested website |

2015 |

2023 |

| No errors |

7 websites |

12 websites |

| Less than 5 errors |

7 websites |

9 websites |

| From 5 to 50 errors |

34 websites |

31 websites |

| More than 50 errors |

18 websites |

14 websites |

If we assume that the target state is the absence of errors in the page code, and the acceptable state is less than 5 errors, we can consider that the degree of compliance with the WCAG 2.0 standard has increased over 8 years from 21.21% to 31.81%. Despite the significant percentage increase (about 50%) in absolute terms, it should be considered that the surveyed sites have not reached a satisfactory level of compliance with the WCAG standard.

The websites of Polish cities with county rights were also directly analysed in terms of visual accessibility. A comparison of the 2015 and 2023 results is presented in the table below:

Table 3.

Visual accessibility analysis of selected websites.

Table 3.

Visual accessibility analysis of selected websites.

| No. |

Feature studied |

2015 |

2023 |

| 1 |

Accessibility statement made available |

0 websites |

54 websites |

| 2 |

Responsiveness of the website |

22 websites |

66 websites |

| 3 |

Changing text size |

26 websites |

41 websites |

| 4 |

Changing contrast settings |

9 websites |

43 websites |

| 5 |

The site has a facilitation package |

26 websites |

13 websites |

| 6 |

The site does not have any facilitation (3-5) |

25 websites |

10 websites |

A physical survey of websites shows that 81.81% of sites have placed a mandatory accessibility statement (in 2015 it was not required). The biggest improvement is in the responsiveness of the surveyed sites. This is mainly due to the development of content management systems (CMS) used by the LGUs. Today, responsive websites have become a common standard.

The number of sites that do not offer any facilities for the visually impaired has decreased (from 37.9% in 2015 to 15.2% in 2023). Unfortunately, the number of sites that offer a full facilitation package - including at least: font size, contrast, marking active links, and marking titles - also decreased (from 39.4% in 2015 to 19.7% in 2023).

In the other parameters studied, there was no significant change if we add up the number of pages that only allow changing contrast and the facilitation package, and the number of pages that allow changing font size and the facilitation package.

4.2. Survey of LGUs

The survey questions yielded the following results:

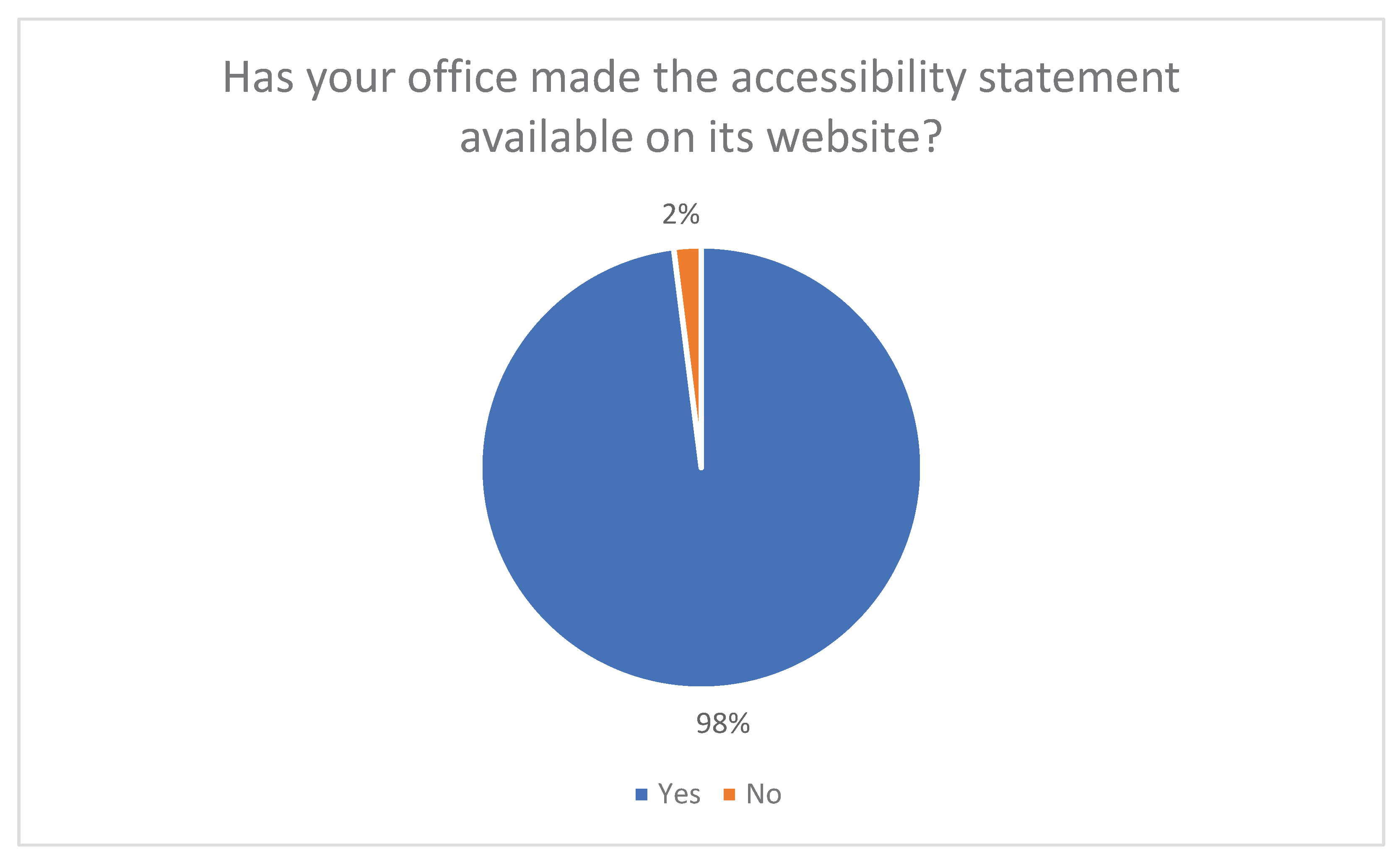

Figure 1.

Declaration of accessibility.

Figure 1.

Declaration of accessibility.

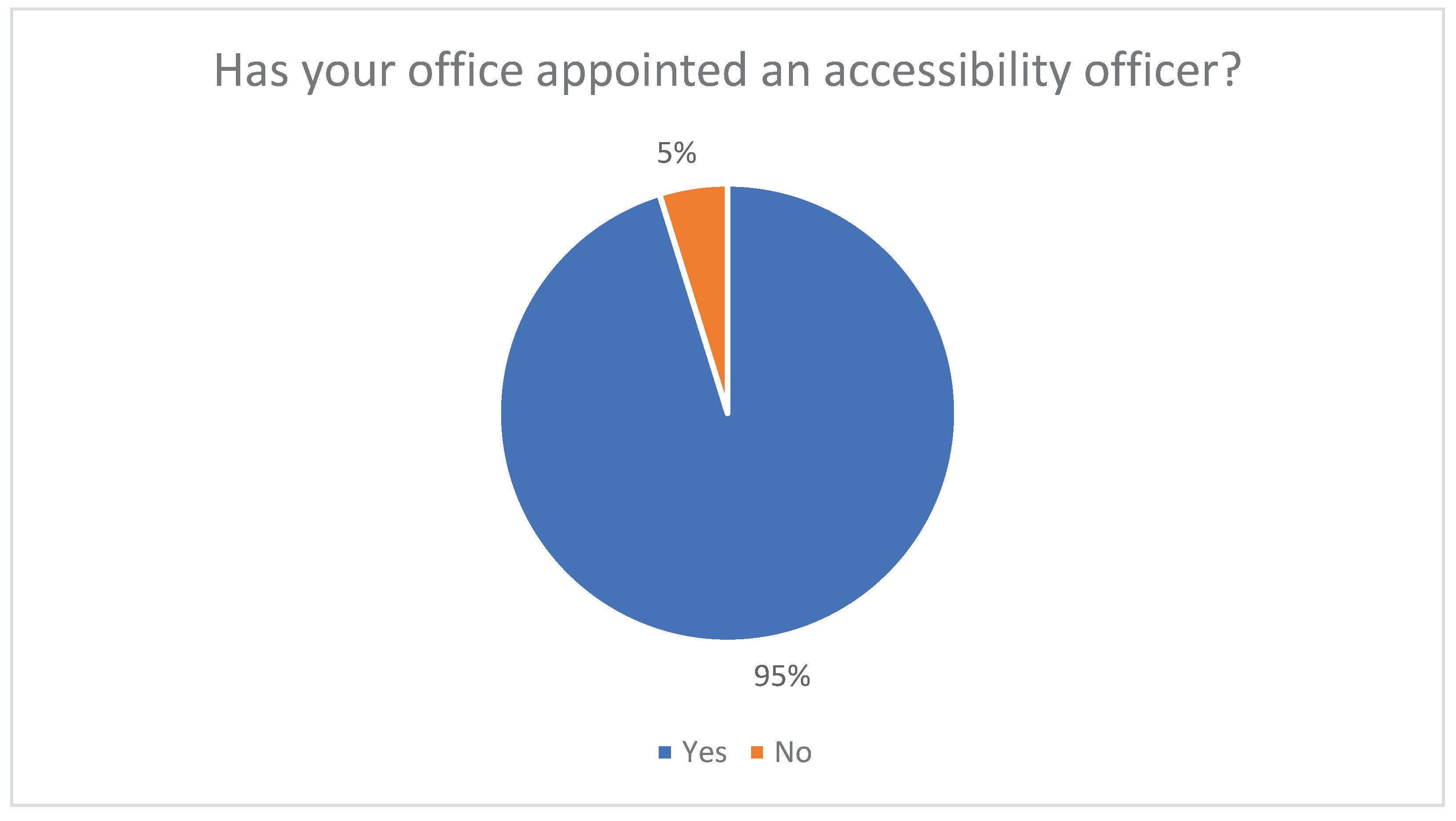

Figure 2.

Accessibility Officer.

Figure 2.

Accessibility Officer.

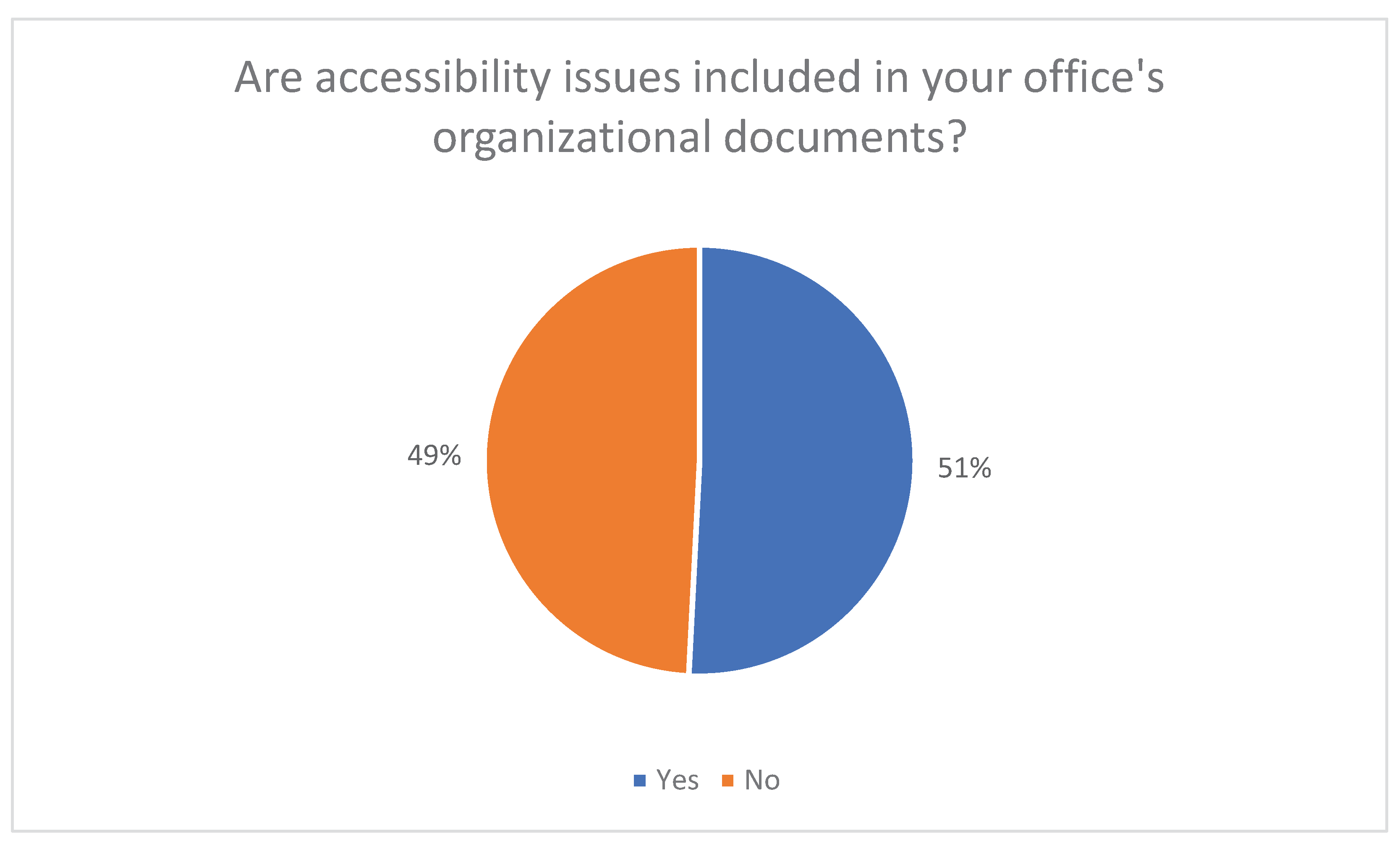

Figure 3.

The problem of accessibility in the organization of the office.

Figure 3.

The problem of accessibility in the organization of the office.

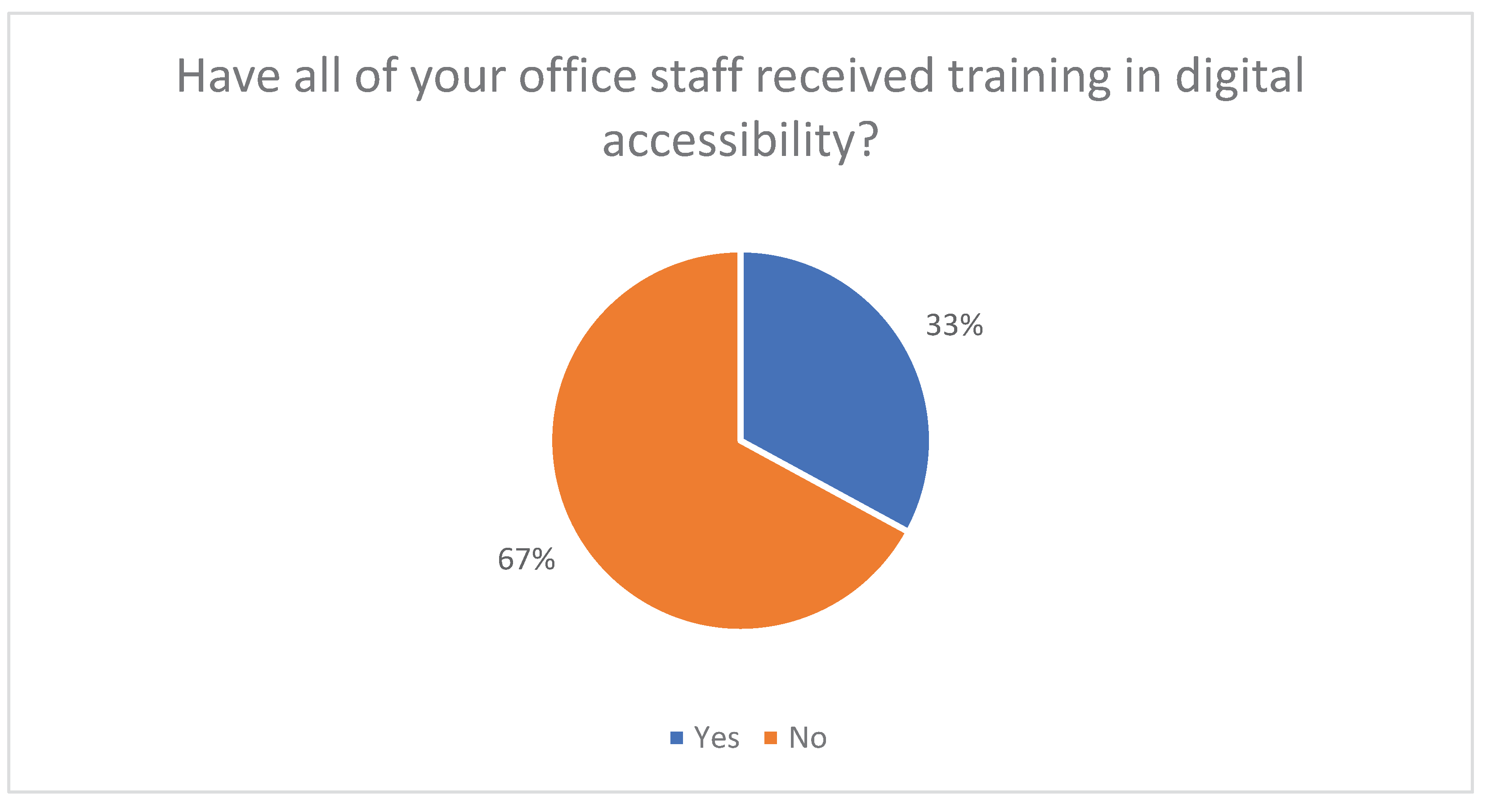

Figure 4.

Employee training.

Figure 4.

Employee training.

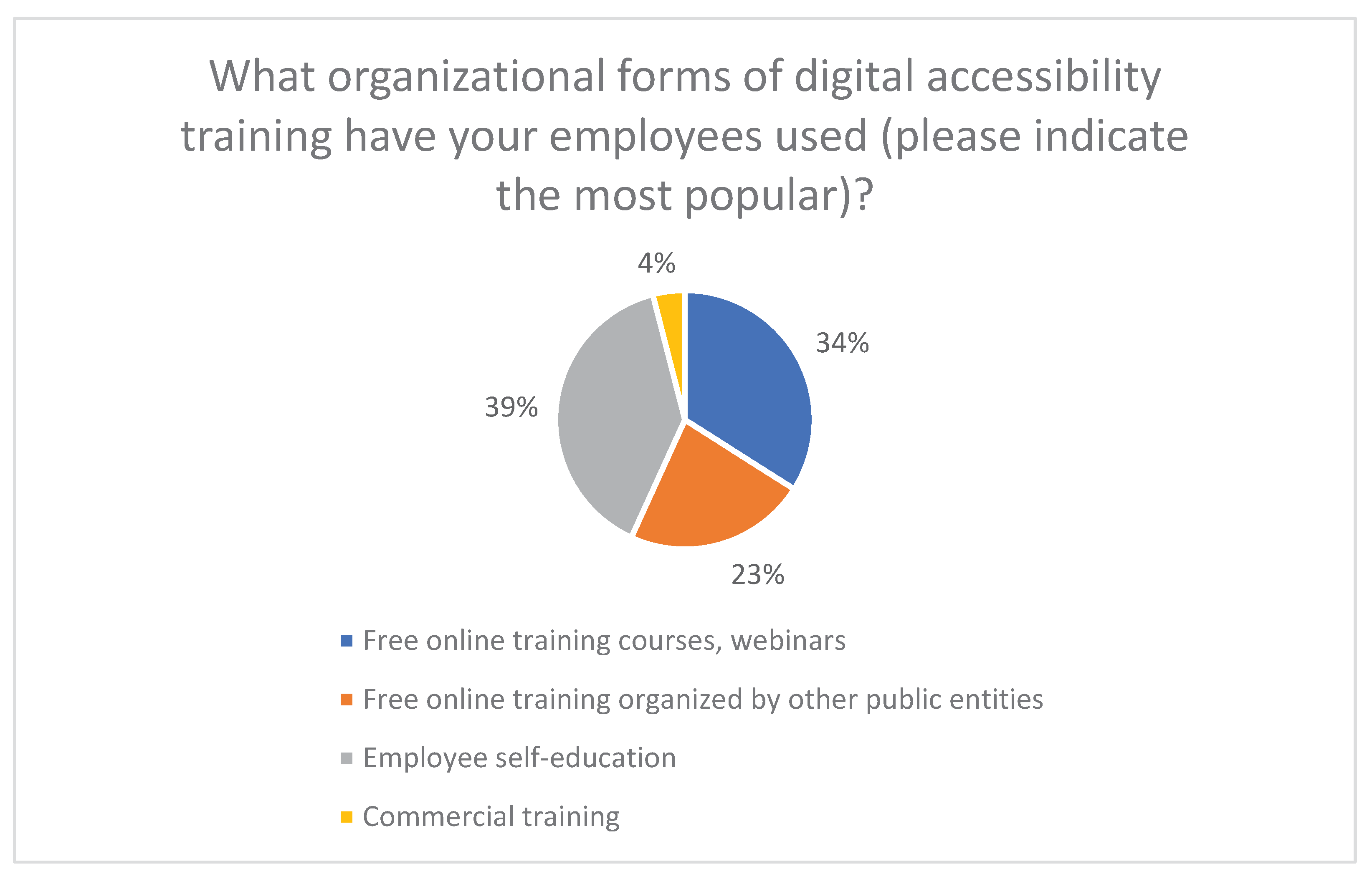

Figure 5.

Accessibility training methods.

Figure 5.

Accessibility training methods.

Surveys conducted among local government units showed that they have implemented formal requirements for digital accessibility: they have left declarations of accessibility of their websites and applications and appointed accessibility officers. The difference between the number of websites with accessibility declarations (for the physical websites surveyed) and the level declared in the survey is due to the difference in the target group of the survey. According to the structure of the local government in Poland, the largest number of municipal governments (rural municipalities and rural-urban municipalities) are characterized by greater formalism in their operations - timely fulfilment of obligations arising directly from the law. Thus, the results of the survey concerning the publication of accessibility declarations should be considered more representative of Polish municipalities.

The level of actual actions taken for the development of the digital accessibility level within the activities of local governments is much worse. Effective actions of the administration are based on efficient internal procedures and the competence of officials. Only 51% of the surveyed offices have introduced considerations related to ensuring digital accessibility into their internal executive procedures, which have a decisive impact on the way local government employees perform their duties. Another important indicator of more than declarative provision of digital accessibility is the level of training of the offices’ employees. Of the surveyed offices, only 33% declared that all employees were trained in digital accessibility. If we additionally take into account that only 4% declared the use of commercial training in this area, and almost 40% relied on self-acquisition of knowledge - the self-education of employees, the level and scope of knowledge acquired by the employees of the local government raises serious doubts.

5. Discussion

The laws in force in Poland as of 2019 and the implementing regulations cited in Part 2 of the article have provided the necessary legal environment for a qualitative change in the digital accessibility of the electronic public services made available by local government administration. Thus, it seems legitimate to conclude that the implementation of formal and legal requirements would result in Polish public entities entering the COVID-19 pandemic period prepared to provide digitally accessible services.

The comparative (physical) surveys of websites conducted did not show a qualitative change in the area of digital accessibility, and in some areas, there was a deterioration in quality. An example of this is the reduction in the number of sites providing a text enlargement function at the level of website functionality. Although all the most popular web browsers have such a function, efficient use of this functionality requires the use of so-called keyboard shortcuts (“ctrl+”, “ctrl-”), and this is a serious limitation, for example for people who cannot use both hands and all fingers efficiently when using a computer keyboard.

The vast majority of LGUs (more than 90% of those surveyed) implement formal requirements, the fulfilment of which is easy to control and sanctioned by law. However, based on the conducted survey, it is impossible to demonstrate that the digital accessibility considerations have been indeed integrated into the standard operations of the local government.

A qualitative leap in the digital accessibility of administration is possible only by incorporating this modus operandi into the operational standards of the offices, as well as by common and efficient training of the officials, and the ability to create digitally accessible documents and content must be added to the minimum standard of digital competencies required from the public administration employees.

Even though due to the COVID-19 pandemic much of the activity of the LGUs has been transferred to the digital world, there has been no noticeable change in the level of digital accessibility of the public e-services that they provide.

References

- EN 301 549 V3.2.1 (2021-03) HARMONISED EUROPEAN STANDARD Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services. Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/301500_301599/301549/03.02.01_60/en_301549v030201p.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Act of on the computerization of the activities of entities performing public tasks (Dz.U. 2005 nr 64 poz. 565). 17 February.

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of on the National Interoperability Framework, minimum requirements for public registers and exchange of information in electronic form, and minimum requirements for ICT systems (Dz.U. 2012 poz. 526). 12 April.

- Act of on digital accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public entities (Dz.U. 2019 poz. 848). 4 April.

- DIRECTIVE (EU) 2016/2102 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of October 26, 2016 on the accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L2102 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Act of 19 July 2019 on ensuring accessibility for people with special needs (Dz. U. 2019 poz. 1696.

- Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on accessibility requirements for products and services. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2019:151:TOC (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Nowak, P.A. ; Nowak, P.A., Ed.; Marshal’s Office of the Lodzkie Region: Poland, 2015; pp. 141–152.Inclusion. In Book Innovations 2015. Information Society development in the New Financial Perspective; Nowak, P.A., Ed.; Marshal’s Office of the Lodzkie Region: Poland, 2015; Marshal’s Office of the Lodzkie Region: Poland, 2015; pp. 141–152. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).