Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

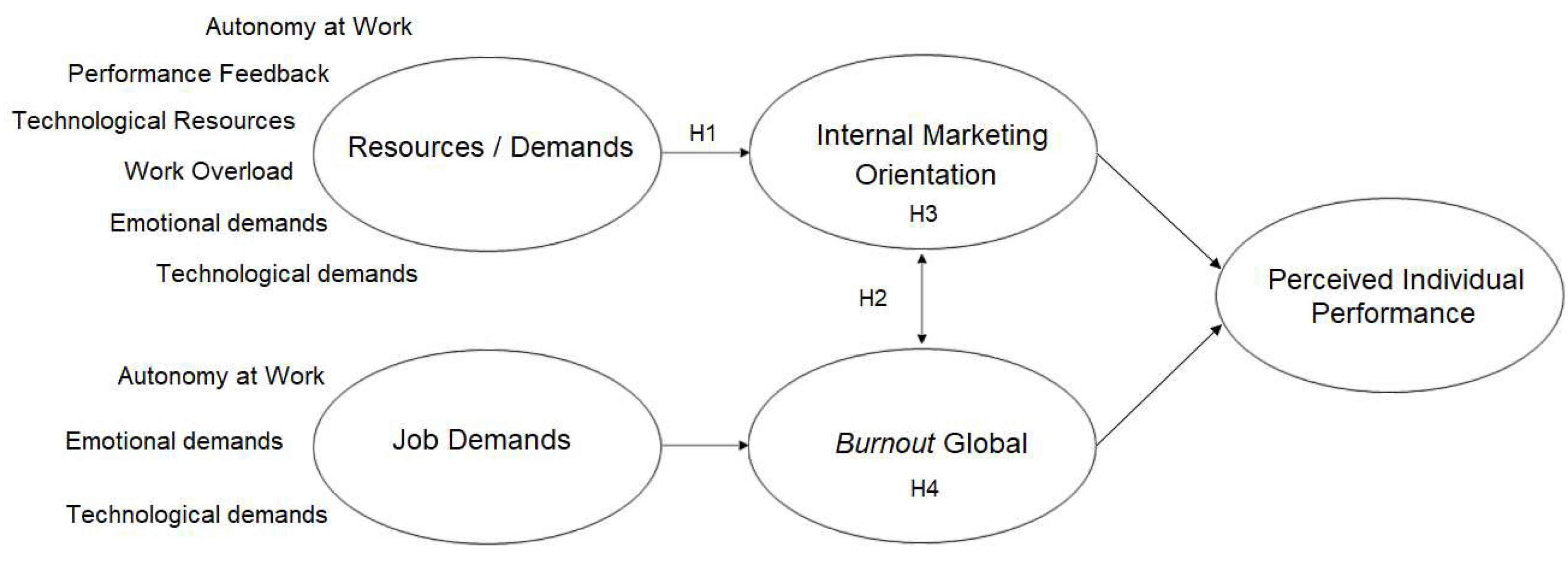

2.1. Job Demands-Resources Model

2.2. Internal Marketing

2.3. Burnout

2.4. Individual Performance

2.5. Theoretical Construction of the Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Sample

3.3. Instrument

4. Results

4.1. Correlations

4.2. Regression

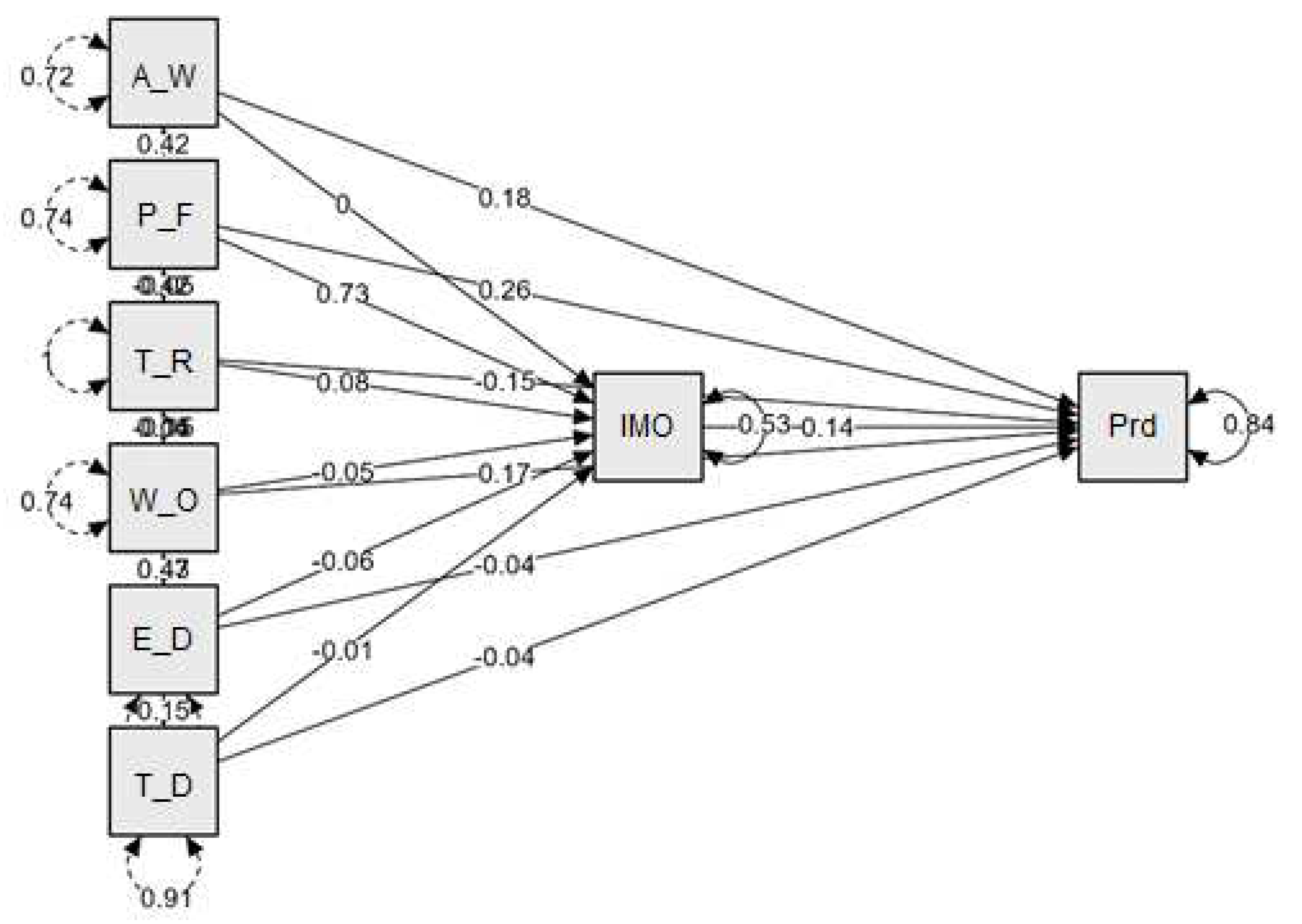

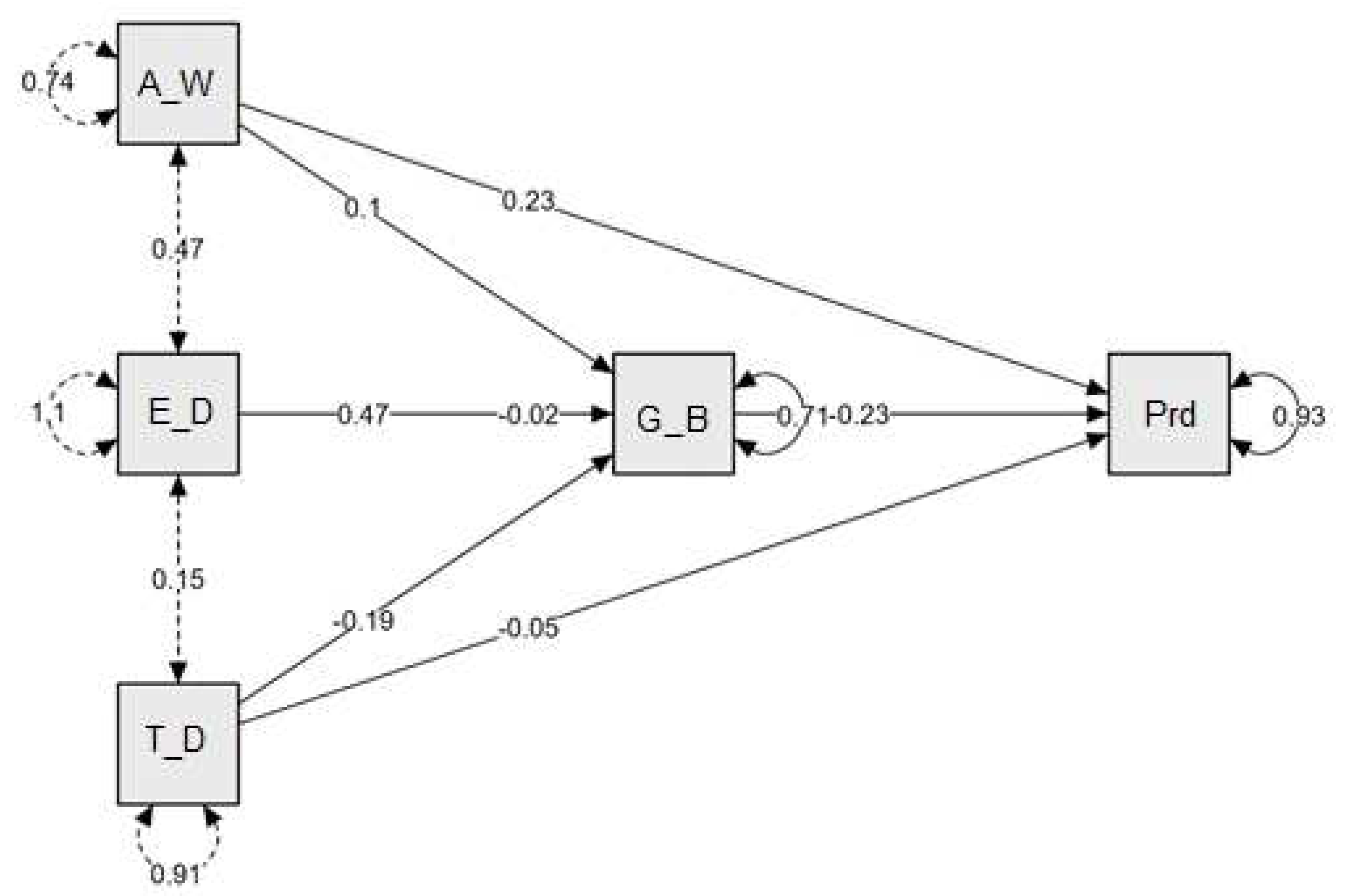

4.3. Mediation

5. Discussion

Future Directions and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, J.; Boukis, A.; Storey, C. Internal Marketing: A Systematic Review. J. Mark. Theo. Pract. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psych. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J.; Perhoniemi, R.; Toppinen-Tanner, S. Positive gain spirals at work: From job resources to work engagement, personal initiative and work-unit innovativeness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, & European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Psychosocial risks in Europe: Prevalence and strategies for prevention. Publications Office of the European Union, 2014Eurofound, & European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Psychosocial risks in Europe: Prevalence and strategies for prevention. Publications Office of the European Union, 2014. /: of the European Union, 2014. https.

- Kalia, M. Assessing the economic impact of stress--the modern day hidden epidemic. Metabolism: clinic. and experim. 2002, 51, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leka, S.; Jain, A. Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: an overview. World Health Organization, 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44428.

- Eurofound. Burnout in the workplace: A review of data and policy responses in the EU. Publications Office of the European Union, 2018. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef18047en.pdf. /: of the European Union, 2018. https.

- Osam, K.; Shuck, B.; Immekus, J. Happiness and healthiness: A replication study. Hum. Res. Devel. Quart. 2020, 31, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ. Dynam. 2017, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A. C. S.; Santos, A. S.; Costa, P. V.; Freitas, C. P. P.; Witte, H.; Schaufeli, W. B. Trabalho e Bem-Estar: Evidências da Relação entre Burnout e Satisfação de Vida. Rev. Aval. Psicol. 2019, 18, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. Internal-market orientation and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. The notion of internal market orientation and employee job satisfaction: Some preliminary evidence. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psych. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psych. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory. Wellbeing 2014, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Wolter, C. The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work and Stress 2019, 33, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A. D.; Chang, M.-L.; Wang, T.-H.; Lai, C.-H. How to create genuine happiness for flight attendants: Effects of internal marketing and work-family interface. J. Air Trans. Manag. 2020, 87, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L. L. The employee as customer. J. Ret. Bank. 1981, 3, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq, M.; Ahmed, P. K. Advances in the internal marketing concept: definition, synthesis and extension. J. Serv. Mark. 2000, 14, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A. K.; Jaworski, B. J. Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. J. Marketing 1990, 54, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lings, I. N. Internal market orientation - Construct and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lings, I. N.; Greenley, G. E. Measuring Internal Market Orientation. J. Serv. Res 2005, 7, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. V.; Gonçalves, G. Organizational Culture, Internal Marketing, and Perceived Organizational Support in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2018, 34, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Barnes, B. R.; Ye, Y. Investigating internal market orientation: is context relevant? Qual. Market Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yen, D. A.; Barnes, B. R.; Huang, Y. A. Enhancing firm performance through internal market orientation and employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2019, 30, 964–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, W. E.; Arbeit, S. P. Selling jobs in the service sector. Business Horizons 1976, 19, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. I. Burnout and Work Engagement: The JDR Approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Org. Behav. 2014, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H. J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Social Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Witte, H.; Desart, S. Manual Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT) – Version 2.0. 2020. https://burnoutassessmenttool.be/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/User-Manual-BAT-version-2.0.pdf.

- Salvagioni, D. A. J.; Melanda, F. N.; Mesas, A. E.; González, A. D.; Gabani, F. L.; Andrade, S. M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. P.; Wiernik, B. M. The Modeling and Assessment of Work Performance. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Org. Behav. 2015, 2, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.; Hildebrandt, V.; van Buuren, S.; van der Beek, A. J.; Vet, H. C. W. Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. Int. J. Prod. Perf. Manag. 2012, 62, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K. B.; Jeung, C.-W.; Yoon, H. J. Investigating the influences of core self-evaluations, job autonomy, and intrinsic motivation on in-role job performance. Hum. Res. Devel. Quart. 2010, 21, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J. W.; Youssef-Morgan, C. M. The positive psychology of mentoring: A longitudinal analysis of psychological capital development and performance in a formal mentoring program. Hum. Res. Devel. Quart. 2019, 30, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L. Measuring Individual Performance. Body@Work, Research Center on Physical Activity, Work and Health, 2014. http://publications.tno.nl/publication/34609635/BTWAre/koopmans-2014-measuring.pdf.

- Nemteanu, M. S.; Dabija, D. C. The influence of internal marketing and job satisfaction on task performance and counterproductive work behavior in an emerging marketing during the covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, W. D.; Kang, S.; Huh, C.; Lee, M. J. (MJ). What factors influence Generation Y’s employee retention in the hospitality industry? An internal marketing approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardes, E. W.; Rodrigues, L. S.; Teixeira, A. Effects of internal marketing on job satisfaction in the banking sector. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1313–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics (5 ed.). Report Number, 2011.

- Pestana, M. H.; Gageiro, J. N. Análise de dados para ciências sociais – A complementaridade do SPSS. Edições Sílabo, 2008.

- Biesanz, J. C.; Falk, C. F.; Savalei, V. Assessing Mediational Models: Testing and Interval Estimation for Indirect Effects. Mult. Behav. Res. 2010, 45, 661–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, Y.; Baek, S. I. The Impact Of Job Demands And Resources On Job Crafting. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2017, 33, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, V. S.; Rodrigues, R. G. Internal Market Orientation in Higher Education Institutions - its Inter-Relations with other Organisational Variables. Pub. Policy Admin. 2012, 11, 690–702. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, A.; Cunha, M. P. Como os climas organizacionais autentizóticos explicam o absentismo, a produtividade e o stresse: um estudo luso-brasileiro (G/no5/2005). Working Papers in Management, Universidade de Aveiro, 2005.

- Lee, M. C. C.; Idris, M. A.; Tuckey, M. Supervisory coaching and performance feedback as mediators of the relationships between leadership styles, work engagement, and turnover intention. Hum. Res. Devel. Int. 2019, 22, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dextras-Gauthier, J.; Marchand, A. Does organizational culture play a role in the development of psychological distress? The Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2018, 29, 1920–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. Antecedents of internal marketing practice: Some preliminary empirical evidence. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2008, 19, 400–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S. P.; Santos, J. V.; Silva, I. S.; Veloso, A.; Brandão, C.; Moura, R. COVID-19 and People Management: The View of Human Resource Managers. Admin. Sciences 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C. F.; Liu, B. Z. Examining job stress and burnout of hotel room attendants: Internal marketing and organizational commitment as moderators. J. Hum. Res. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 16, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, S. Performance Feedback, Goal Clarity, and Public Employees’ Performance in Public Organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieong, C. Y.; Lam, D. Role of Internal Marketing on Employees’ Perceived Job Performance in an Asian Integrated Resort. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Esposito, A.; Sciarra, I.; Chiappetta, M. Definition, symptoms and risk of techno-stress: a systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Envir. Health 2019, 92, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, S.; Arslan, A.; Kilinç, S. The moderating roles of technological self-efficacy and time management in the technostress and employee performance relationship through burnout. Inf. Techn. & People 2021, 34, 1890–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovic, M.; Gahan, P.; Olsen, J.; Gulyas, A.; Shallcross, D.; Mendoza, A. Exploring the adoption of virtual work: the role of virtual work self-efficacy and virtual work climate. The Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2021, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T. M.; Boehm, S. A. Am I outdated? The role of strengths use support and friendship opportunities for coping with technological insecurity. Comp. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 2 | .414** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 3 | .675** | .577** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 4 | .387** | .464** | .484** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 5 | −.033 | −.072 | .073 | .073 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 6 | −.214** | −.189** | −.172** | −.152** | .522** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 7 | .136** | .173** | .214** | .445** | .278** | .147** | 1.000 | |||||

| 8 | −.298** | −.355** | −.354** | −.291** | .445** | .543** | −.058 | 1.000 | ||||

| 9 | −.385** | −.434** | −.492** | −.286** | .085 | .356** | −.154** | .651** | 1.000 | |||

| 10 | −.156** | −.209** | −.222** | −.140** | .196** | .322** | .013 | .553** | .550** | 1.000 | ||

| 11 | −.279** | −.259** | −.343** | −.256** | .176** | .454** | −.092 | .599** | .697** | .678** | 1.000 | |

| 12 | .292** | .258** | .342** | .079 | .107* | −.043 | .023 | −.061 | −.226** | −.167** | −.196** | 1.000 |

| Hypothesis / Dimension (H1) |

Global IMO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coeffcient | z-value | p-value | |

| Autonomy at Work | .016 | .337 | .737 |

| Performance Feedback | .629 | 12.74 | < .001 |

| Technological Resources | .075 | 1.65 | .100 |

| r2 | .460 | ||

| p-value | < .001 | ||

| Work overload | .065 | 1.08 | .282 |

| Emotional Demands | −.271 | −4.60 | < .001 |

| Technological Demands | .158 | 3.01 | .003 |

| r2 | .077 | ||

| p-value | < .001 | ||

| Hypothesis / Path relation | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | z-value | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| AW → Prd | .178 | .072 | 2.475 | .013 | .009 | .352 |

| PF → Prd | .263 | .087 | 3.033 | .002 | .103 | .438 |

| TR → Prd | −.154 | .062 | −2.479 | .013 | −.288 | −.025 |

| WO → Prd | .174 | .068 | 2.547 | .011 | .021 | .317 |

| ED → Prd | −.040 | .056 | −.721 | .471 | −.166 | .087 |

| TD → Pro | −.038 | .058 | −.654 | .513 | −.166 | .104 |

| Indirect Effect (H3) | ||||||

| AW → IMO → Prd | −2.105e-4 | .008 | −.027 | .979 | −.025 | .016 |

| PF → IMO → Prd | .100 | .049 | 2.066 | .039 | .007 | .217 |

| TR → IMO → Prd | .011 | .009 | 1.290 | .197 | −.001 | .044 |

| WO → IMO → Prd | −.007 | .008 | −.895 | .371 | −.037 | .005 |

| ED → IMO → Prd | −.009 | .007 | −1.193 | .233 | −.038 | .002 |

| TD → IMO → Prd | −.002 | .006 | −.275 | .783 | −.021 | .011 |

| Total Effect | ||||||

| AW → Prd | .178 | .072 | 2.458 | .014 | .005 | .349 |

| PF → Prd | .363 | .073 | 5.003 | < .001 | .226 | .503 |

| TR → Prd | −.143 | .062 | −2.296 | .022 | −.272 | −.015 |

| WO → Prd | .166 | .068 | 2.428 | .015 | .018 | .314 |

| ED → Prd | −.049 | .056 | −.876 | .381 | −.176 | .078 |

| TD → Prd | −.040 | .059 | −.680 | .496 | −.166 | .099 |

| Path relation | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | z-value | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| AW → Prd | .232 | .071 | 3.273 | .001 | .079 | .381 |

| ED → Prd | −.021 | .063 | −.326 | .745 | −.170 | .132 |

| TD → Prd | −.052 | .056 | −.922 | .357 | −.177 | .078 |

| Indirect Effect (H4) | ||||||

| AW → GB → Prd | −.023 | .015 | −1.476 | .140 | −.064 | .004 |

| ED → GB → Prd | −.110 | .031 | −3.594 | < .001 | −.198 | −.039 |

| TD → GB → Prd | .045 | .016 | 2.792 | .005 | .012 | .097 |

| Total Effect | ||||||

| AW → Prd | .209 | .072 | 2.904 | .004 | .048 | .359 |

| ED → Prd | −.130 | .058 | −2.257 | .024 | −.247 | −.014 |

| TD → Prd | −.007 | .056 | −.127 | .899 | −.141 | .126 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).