1. Introduction

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has reduced global migration flows by 27% [

1]. Besides this, several other factors such as increased health concerns, job losses, and travel restrictions have also had a considerable negative impact on many migrant workers sending remittances to families in the country. A report shows that in 2020, the average flow in the sector for countries receiving global remittances declined by 1.5% to a total of

$711 billion [

2]. However, over the next two years, the pandemic coincided with some easing of the bottlenecks, i.e. as international borders opened and visa approvals resumed, the international migration system regained some normal momentum, resulting in increased global remittance flows. According to World Bank data, in 2021, total global remittances were estimated at

$781 billion and further increased to

$794 billion in 2022. [

3]. However, amid the growing uncertainty and elevated inflation worldwide that adversely affected migrants’ real income and their remittances. Bangladesh’s remittance earnings for the financial year 2022 stood at USD 21031.68 million and the remittance-GDP ratio, remittance-export earnings ratio, and remittance-import payments ratio were 4.56 percent, 42.71 percent, and 25.49 percent respectively in the financial year 2022 [

4].

The motivations for sending remittances are mainly composed of a summation of socioeconomic reasons, such as altruism, investment, self-interest, debt-repayment, and social commitment purposes [

5,

6]. Moreover, an ample body of literature has risen on the impact of household remittances on poverty, inequality, investment in small enterprises, resource-mobilization, health, and education [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, studies of the impact of remittances on digital financial inclusion from the perspective of Bangladesh are rare. In this study, using a survey of remittance-receiving households in Bangladesh, a hypothesis is tested that remittances affect the use of digital financial services.

Evidence from previous studies shows that migrant household remittances may affect different types of financial inclusion through multiple pathways. Firstly, sending remittances by official channels can rise household needs as a bank saving increases and government support. Since different fixed costs and variable expenses are associated with sending remittances, migrants may also send remittances irregularly to families, which can save a family extra cash in a limited period. It may rise households’ requirements for savings accounts for keeping the money of any fugitive remaining cash from the hairiness of remittances [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Secondly, if migrants send remittances through formal channels, their families can be informed by financial institutions about their various bank loan products. Moreover, since financial institutions keep important information about remittance-receiving households, the trust of financial institutions to extend various types of loans to these households can be increased [

15,

18]. Thirdly, financial institutions through the accumulation of remittances not only help meet the credit needs of remittance-receiving households but also extend to other households and organizations [

19,

20,

21].

The basic objective of this study is to find the effect of migrant household remittances on digital financial services in Bangladesh. Specifically, to observe what induces the use of financial inclusions among Bangladeshi remittance recipient households and whether there is any variation in the use of such financial services among non-remittance recipient households. The outcomes also have enlightenments for whether an increase in migrant household remittances will increase the digital financial product position of Bangladeshi households.

To solve the research problems, this paper applies an estimation of Instrumental Variables (IV) and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis. Therefore, this study uses migrant network effects to control for expected endogenous effects of migrant household remittances to get an impartial and coherent analysis of the effect of remittances on financial services. There may be endogeneity of migrant remittances received by households, as this precludes the use of an instrumental variable technique that we know generally depends on the probabilities of causal and reverse causality. In addition, the PSM method was adopted as a robustness test to verify the results derived from the study hypothesis.

The outcomes of this study explore that households receiving remittances in Bangladesh increase the probability of using savings accounts and adopting mobile banking. This study closely relates to an increasing body of literature that conceptualizes the impact of migrant household remittances on financial products and it provides extensive literature that explains the impact of migrant household remittances on the financial area and national economic development. [

14,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, this paper distinguishes itself from the existing literature from a developing country’s perspective specifically in Bangladesh. As we know that Bangladesh was the 7th highest recipient of remittances in the world with almost

$22.1 billion in 2021 and was the third-highest recipient of remittances in South Asia [

22]. This contributes a distinctly captivating study for the region to conduct empirical research.

The contemporary relevance of this paper and the benefits of substantive financial services are emphasized in the literature. Empirical evidence shows that remittances increase consumption, income, employment, education, access to microfinance, and mental health [

23,

24,

25]. Moreover, remittance ingoing to microfinance may assist in enormous financing opportunities in commercially viable products, increase the number of start-ups business, and improve the profitability of existing enterprises [

26]. Additionally, household savings have been shown to increase access to saving [

27,

28], investment [

29], consumption [

29,

30], and women's empowerment. Eventually, financial inclusion is significantly correlated with household economic development, which may provide a route to investment and economic growth in the development of the state [

31,

32,

33].

The rest of this article expands upon as follows: section 2, elaborates on the background to financial inclusion in Bangladesh, section 3 the relevant literature is discussed, section 4 describes the data and empirical methodology, section 5 presents the empirical findings and

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Background to digital financial inclusion in Bangladesh

Recently, the political and economic slogan in Bangladesh is to build a Digital Bangladesh. However, in the era of cyber technology, no institutional definition has been made for building a digital Bangladesh. However, what can be understood is that the main goal is to make the country's financial sector rapidly develop and pioneer through various inclusions using modern technology. A large population of Bangladesh is still immersed in the darkness of illiteracy, but the use of mobile phones has become a very easy matter even for this illiterate population.

The first mobile banking service was launched in Bangladesh in 2010. Currently, there are 15 mobile banking services in Bangladesh. First Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited launched their mobile banking service and the mobile banking service they operated was called Rocket. Soon after the arrival of Rocket in 2011 as a subsidiary of BRAC Bank, Bikash was launched as the second mobile banking service, which now has more than 5 crore mobile banking users. At present, development services are available in all parts of the country in cities, towns, villages, and towns. Then many more mobile banking services were added. The cash mobile banking service was launched in 2019. Despite being relatively new, the cash mobile banking service operated by Bangladesh Postal Department has gained 40 million subscribers much faster than development. On March 17, 2021, "Upay", one of the country's mobile financial services and a subsidiary of UCB Bank, started its journey as the country's fourth mobile financial service. Which has already gained huge popularity in the country. Another new mobile financial service trust Asiata Pay or "TAP" was launched in the country last year in 2021.

The service can be used on any mobile phone with a subscription to any of the existing six mobile operators in Bangladesh. Under mobile banking services, banks appoint banking agents to perform banking activities on their behalf, such as opening mobile banking accounts and providing cash services (receipts and payments). Cash withdrawals from a mobile account can also be made from an ATM that validates each transaction by 'mobile phone and PIN' instead of 'card and PIN'. Other services provided through the mobile banking system are person-to-person (money transfer), person-to-business (commercial payments, utility bill payments), business-to-person (salary/commission disbursement), and government-to-person (Disbursement of Government Allowance) transactions.

Currently, remittances can be sent directly from 65 countries of the world through mobile banking. Migrants who want to send money to their family from abroad can easily send money to the family's mobile number. In this case, Bikash is a popular mobile banking service in Bangladesh. Many times, expatriates are cheated by trying to send their hard-earned money to their families through others. Therefore, if expatriates send money from abroad directly to their family's mobile number, there is no opportunity for anyone else to embezzle that money. Expatriate Bangladeshis living abroad can easily and conveniently send money to their loved ones' mobile accounts in Bangladesh through authorized and listed foreign banks, money transfer organizations, and money exchange houses.

3. Literature Review

Recent studies have examined the impact of remittances on different household activities, for instance, entrepreneurship [

34,

35,

36,

37], poverty and inequality [

10,

38], as well as education and wellness [

8]. Evidence from developing nations shows that remittance-receiving households are generally more motivated to invest in the housing sector [

35,

39]. Moreover, it also shows that it has a positive impact on employment, productivity, and micro-macroeconomic development. However, some also argue that remittances can discourage labor supply, as a result, which creates a cycle of financial dependence by reducing recipients' motivation to work [

40]. Furthermore, in most countries, remittance-recipient households tend to spend more on various types of luxury goods than investing in physical assets [

40,

41,

42].

In previous studies, research on remittances and financial inclusion has gained much concentration on mainly among policy development experts. This increasing interest in their financial inclusion is day-by-day driving towards financial inclusion in households, societies, and financial development [

27,

28,

29,

43]. Hence, in this background, a rising body of literature is building toward understanding the implications and impacts of household remittance receipts and new financial inclusion [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The existing literature thus far provides us with two main perspectives on the association between migrant household remittances and financial inclusion. Firstly, remittances are a simple credit alternative. This ramification is from a theoretical and also analytical framework in which an imperfect credit market exists where remittances assist marginal and liquidity-strapped households’ investment in physical or human capital and alleviate the effect of shocks by financial crises [

37,

44,

45,

46]. Secondly, there is an increasing body of evidence that remittances have a significant impact on savings at both the macro and micro economic levels [

14,

16,

47,

48]. A few of the causes for the positive effect of remittances comprise the weighting of remittances in the savings index, which can essentially create demand for remittance recipients in deposit accounts; expanding knowledge about financial inclusion products; matching information from other users; and above all enhancing some of their financial opportunities and creditworthiness by receiving remittances s [

17,

20].

From the above review, it is clear that there is a limitation of the literature on financial inclusion related to remittances and socioeconomic outcomes in households, especially in developing countries. It is therefore hoped that this study will be able to contribute to the existing literature in this field, which will help inform policy development and discussions.

4. Methods

This paper uses a household survey that conducts a stratified random sampling method that includes 16 districts out of the 8 divisions at the first-order administrative level (consisting of 64 districts) and the capital city in Bangladesh and interviewed 2,165 households in 2022-2023. The household survey was a one-time collection of data on migration and remittances from one migrant household. Among the important data, there were mainly preferences for the use of family financial inclusion. For example, whether the household has its own savings account, the extent to which the household uses mobile banking, and the extent to which ATM cards are used for financial transactions. Indeed, the focus of this article is to examine the impact of household remittance receipts on access to digital financial inclusion.

This paper analyzes the relationship between household remittance receipt and the use of digital financial inclusion using the following model:

where,

h = the household

FinI = 1, if uses of financial inclusion, and otherwise=0

Rm = households’ covariates

ε = the error term

In this study, follow [

14] by determining the controlling variables which are the age of the household head, gender of the household head, household head’s level of education, the household size, dependents, female members, destination of migrants, activity of migrant and regional as a dummy. An empirical estimated equation (i) using a Linear Probability Model. This study also describes the marginal impacts of Probit Regressions for the diverse financial services determinatives.

Using the two models such as linear probability and probit model can rise an important problem which means the hypotheses that were omitted may be endogenous due to the omitted variables. Research estimates may be biased in cases where omitted variables are related to households' likelihood of receiving remittances and using financial inclusion. Therefore, this problem is solved using an instrumental variable analysis. Moreover, opposite causation may influence these analyses from equation (i) owing to the fact that access to financial inclusions may rise the simplicity of sending-receiving remittances. Thus, this probably increases the probability of migrants’ remittances inflow.

This study adopts an instrumental variable because it can eliminate potential bias arising from the possible endogeneity of the results. In the migration and remittances literature, these instruments are mainly called migrant network impacts. [

7,

14,

49]. A Migrant’s destination or network may influence the probability of migration and the receipt of remittances by their family, which may serve as an instrument for the migrant network effect. Indeed, it is not expected that migrant network effects will influence households' access to and use of digital financial inclusion.

The reliability and validity of the identification strategy used in this article depend on the instrument (the network effect of migrants) satisfying both assumptions. Firstly, migrants' remittances are positively correlated with the instrumental variables analysis. Secondly, those factors that may always affect household financial inclusion are assumed, namely those that are most likely to be correlated with the instruments. Additionally, it is assumed that the instrument meets exclusion restrictions. From this, it is clear that the instrument does not affect the direct effect outcome, financial service, without the first-level regression.

Robustness tests are performed using population Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to discourse potential selection bias connecting from the selection of unobservable characteristics that might create a relationship between the propensity to receive remittances and the likelihood of using financial services. Migration and remittance studies show that the PSM approach allows for potential selection corrections by differentiating from remittance-receiving households to non-remittance-receiving households depend on their propensity score [

50,

51].

In the Propensity Score Matching approach, the status of financial inclusion is defined as households not receiving remittances as the control group and households receiving remittances as the treatment group which exhibits opposite results. Various studies have shown that PSM provides more accurate non-experimental estimates when households self-select into a treatment group than other estimation methods [

52]. Below are the equations:

Let

Ri = 1 (if received remittances)

Ri = 0 if not received remittances

F1i = financial Inclusion – a household receiving remittances

F

0i = financial inclusion-a household non-receiving remittances

Above equation (ii) shows that it is impossible to observe two distinct types of families at the same time. Therefore, the result of household remittance receipts could be examined, but the same result may not be observed here in the non-existence of a remittance receipt. In fact, the Propensity Score Matching estimations depend on unpredictable independence acceptance, which explains conditional on Z, the dynamic effects are independent of the treatment positions (receiving remittances). The treatment assignment is as proper as random, since controlling for the observable covariates Z [

53].

Applying propensity score matching, the parameter of interest in this study is the average treatment effect on treatment, which is calculated by subtracting the average treatment effect of the treated group from the control on a given propensity score.

Thus,

An Average Treatment Effect on Treatment (ATET) = K [F ⃓ Y =1, L(Z)] - K [F ⃓ R = 0, L (Z)]

5. Findings

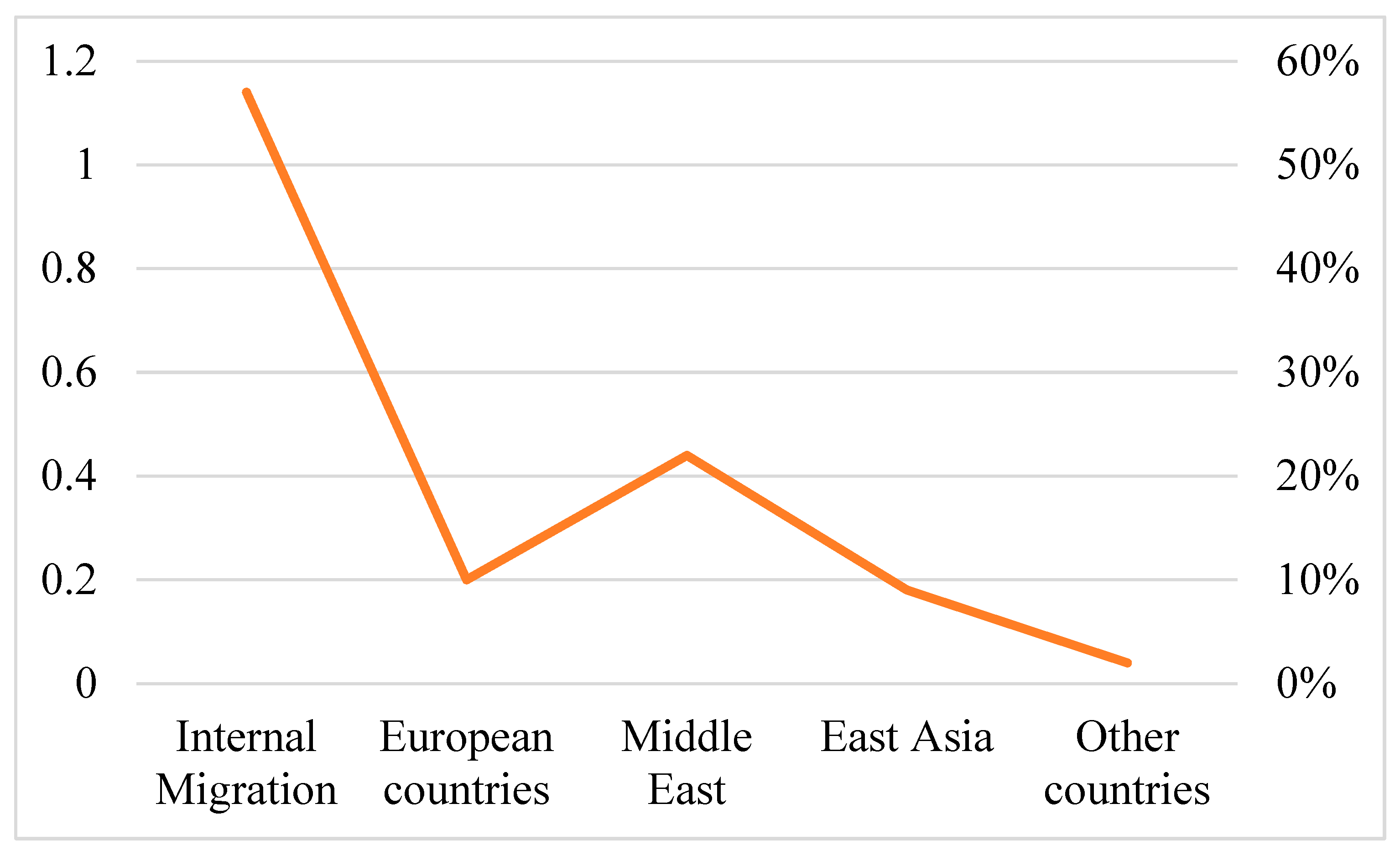

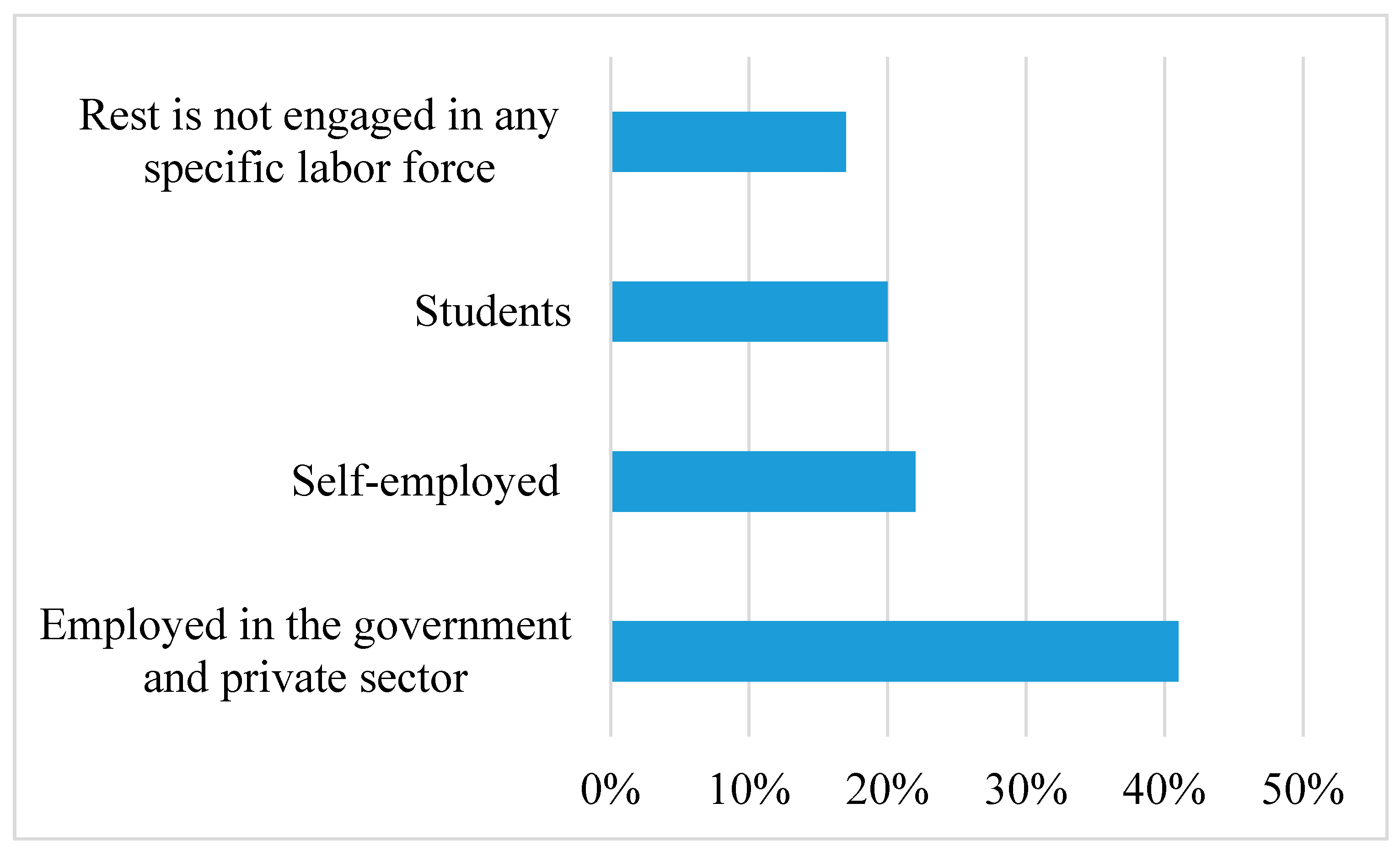

Migrants have migrated to different cities within the country and also outside the country. As shown in Figure 1.1, about 57% of migrants migrated within Bangladesh (mainly from rural to urban), while among other countries 10% migrated to various European countries 10%, 22% to the Middle East, East Asia 9% and 3% to other destinations. Among total internal migrants, 41% are employed in the government and private sector, 22% are self-employed, 20% are students, and the residue is not engaged in any specific labor force or is engaged in other activities as shown in Figure 1.2. The majority of migrants in European countries are involved in paid employment (63%) and others are engaged in small-scale trade. Most (97%) from the Middle East and other countries are engaged in paid employment, but there are also some students from other countries.

Figure 1.1.

Destination of Migrants (Authors Computation).

Figure 1.1.

Destination of Migrants (Authors Computation).

Figure 1.2.

Employment Status of Internal Migrants (Authors Computation).

Figure 1.2.

Employment Status of Internal Migrants (Authors Computation).

Table 1.1 presents descriptive statistics of household characteristics. The average annual remittance of each family was BDT 475,000, of which 87% was international remittance and 13% was internal remittance. Sixty-three percent of households hold their own bank account, 21% used mobile banking, and only 7% used ATM cards for cash transactions. There was no significant numerical difference between rural and urban participants. The average adult has a little more than 9 years of formal education, but the average head of household has a little more than 10 years of formal education. The average household size is about 4 people and the age of the household head is 36 years. Households headed by a female constitute 37.8 percent of total households, while the proportion of female members in a household is 32.5%. The family dependency ratio is seen at 43.4%.

Table 1.1.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 1.1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

| Remittance (Internal) |

163.211 |

628.332 |

| Remittance (International) |

144.334 |

598.243 |

| The household has a bank account |

0.635 |

0.534 |

| Households use mobile banking |

0.215 |

0.521 |

| Households use an ATM card |

0.072 |

0.543 |

| Household head level of educational |

10.324 |

5.361 |

| Number of household members |

4.057 |

3.145 |

| The average age of the household member |

36.325 |

8.822 |

| Dependents (%) |

43.715 |

21.825 |

| Female member of the household (%) |

37.567 |

18.354 |

| Region (Urban) |

0.497 |

0.499 |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

0.169 |

0.457 |

Table 1.2 presents the mean difference that represents the characteristics of households of whether remittance receive or not. In this paper, financial inclusion is basically proxied with three indicators: firstly, the household having its own bank account, secondly the household using mobile for financial transactions, and thirdly the household using ATM cards for financial needs. Analysis of the results indicates that the majority of households who received remittances have at least one bank account. Moreover, remittances received by households that used mobile banking for financial needs were about 21.8 percent and only 9.3 percent that used ATM cards for financial needs. It is noted here that most of the women-headed families who have received remittances live in rural villages.

Table 1.2.

Mean Difference (t-test).

Table 1.2.

Mean Difference (t-test).

| Variable |

Received Remittance |

Difference |

| |

No |

Yes |

|

| Remittance (Internal) |

|

|

|

| Remittance (International) |

|

|

|

| The household has a bank account |

0.621 |

0.721 |

|

| |

(0.415) |

(0.422) |

-0.047**

|

| Households use mobile banking |

0.315 |

0.288 |

|

| |

(0.427) |

(0.417) |

0.071**

|

| Households use an ATM card |

0.746 |

0.644 |

|

| |

(0.409) |

(0.438) |

0.077**

|

| Household head level of educational |

10.334 |

9.385 |

|

| |

(4.147) |

(4.333) |

0.217 |

| Number of household members |

4.879 |

4.709 |

|

| |

(1.726) |

(2.357) |

-0.411***

|

| The average age of the household member |

36.384 |

39.821 |

|

| |

(8.373) |

(9.217) |

-1.784***

|

| Dependents (%) |

34.331 |

29.473 |

|

| |

(23.928) |

(23.548) |

3.245***

|

| Female member of the household (%) |

31.154 |

33.825 |

|

| |

(15.377) |

(16.342) |

-2.316**

|

| Region (Urban) |

0.498 |

0.572 |

|

| |

(0.428) |

(0.433) |

-0.137***

|

| Gender (Female migrant) |

0.087 |

0.549 |

|

| |

(0.208) |

(0.477) |

-0.077***

|

Probit regression results are presented in Table 1.3 below and the disaggregated (internal and international remittances) analyses are presented in Table 1.4 and Table 1.5 respectively. Both Table 1.4 and Table 1.5 use linear probabilistic regression estimation techniques. Each table shows in different columns, the effect of migrant remittances on the probability that the household has a bank account, households use mobile banking and household members use ATM cards respectively for their financial transactions.

Table 1.3.

Total Remittance: Probit regression results.

Table 1.3.

Total Remittance: Probit regression results.

| |

Total Remittance |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.007***(0.001) |

0.003(0.002) |

0.002(0.002) |

| The Age of household head |

0.035***(0.002) |

0.015***(0.004) |

0.026***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.028***(0.007) |

0.006(0.008) |

0.004(0.007) |

| The Household head level of educational |

0(0.002) |

-0.006***(0.001) |

-0.004***(0.001) |

| Female household head (%) |

0(0.002) |

0(0.002) |

-0.001**(0.002) |

| Destination |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

0.023(0.033) |

0.007(0.022) |

0.061**(0.022) |

| |

Middle East |

0.006(0.034) |

0.221**(0.044) |

0.062(0.048) |

| |

East Asia |

-0.022(0.061) |

-0.082(0.067) |

-0.025(0.065) |

| |

Other countries |

0.051(0.062) |

0.043(0.202) |

0.006(0.073) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.050*(0.018) |

-0.022(0.032) |

-0.035(0.037) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

0.002(0.017) |

0.006(0.044) |

-0.030(0.280) |

| |

Student |

-0.02(0.072) |

0.232(0.085) |

-0.024(0.078) |

| |

Unemployment |

0(0.04) |

0.013(0.20) |

0.020(0.072) |

| |

Others |

-0.022(0.072) |

0.043(0.033) |

-0.008(0.077) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.075**(0.24) |

-0.46(0.034) |

-0.071*(0.030) |

| Const. |

0.028(0.084) |

0.477(0.243) |

0.424***(0.221) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

0.411 |

0.156 |

0.283 |

Probit regression results indicate that the positive impact of remittances was seen on all financial inclusion indicators for households, but their coefficients are significant that is in determining if a family member holds a bank account. This analysis retains regardless of total remittances (Table 1.3). Additionally, Table 1.4 and Table 1.5, explore that having at least one bank account in the household receiving remittances increases the likelihood of financial inclusion, in other words, a unit change in migrant remittances increases the probability of household members holding a bank account. This outcome is certainly plausible given that having a bank account can reduce the expenditure of remittance transfers, thereby increasing migrant remittance flows.

Table 1.4.

Internal Remittance: Probit regression results.

Table 1.4.

Internal Remittance: Probit regression results.

| |

Remittance (Internal) |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.007***(0.003) |

0.003(0.002) |

0.002(0.002) |

| The Age of household head |

0.034***(0.002) |

0.031***(0.004) |

0.016***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.028***(0.007) |

0.006(0.008) |

0.004(0.007) |

| The Household head level of educational |

0.0(0.002) |

-0.006***(0.003) |

-0.003***(0.002) |

| Female household head (%) |

0.0(0.002) |

-0.002(0.002) |

-0.002(0.001) |

| Destination |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

0.017(0.033) |

0.008(0.022) |

0.062(0.042) |

| |

Middle East |

0.02(0.034) |

0.211**(0.049) |

0.063(0.048) |

| |

East Asia |

-0.022(0.042) |

-0.081(0.068) |

-0.029(0.088) |

| |

Other countries |

0.043(0.061) |

0.042(0.011) |

0.007(0.073) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.044*(0.018) |

-0.011(0.032) |

-0.037(0.029) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

0.003(0.019) |

0.007(0.028) |

-0.028(0.041) |

| |

Student |

-0.020(0.072) |

0.021(0.083) |

-0.023(0.078) |

| |

Unemployment |

0.0(0.040) |

-0.072(0.075) |

0.010(0.071) |

| |

Others |

-0.024(0.071) |

0.019(0.101) |

-0.008(0.070) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.072**(0.024) |

-0.048(0.039) |

-0.072*(0.030) |

| Const. |

0.041(0.081) |

0.475***(0.135) |

0.049***(0.133) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

0.411 |

0.204 |

0.283 |

Table 1.5.

International Remittance: Probit regression results.

Table 1.5.

International Remittance: Probit regression results.

| |

Remittance (International) |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.007***(0.003) |

0.003(0.004) |

0.002(0.004) |

| The Age of household head |

0.039***((0.004) |

0.034***(0.004) |

0.026***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.030***(0.007) |

0.007(0.008) |

0.004(0.007) |

| The Household head level of educational |

0.0(0.001) |

-0.007***(0.003) |

-0.004***(0.003) |

| Female household head (%) |

0.0(0.001) |

-0.002*(0.001) |

-0.001**(0.002) |

| Destination |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

-0.006(0.037) |

0.004(0.048) |

0.076*(0.043) |

| |

Middle East |

-0.020(0.031) |

-0.107**(0.049) |

0.077(0.072) |

| |

East Asia |

-0.041(0.041) |

-0.088(0.068) |

-0.039(0.071) |

| |

Other countries |

0.021(0.064) |

0.033(0.216) |

0.001(0.076) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.074**(0.031) |

-0.017(0.030) |

-0.040(0.027) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

-0.020(0.015) |

-0.011(0.027) |

-0.044(0.029) |

| |

Student |

-0.048(0.071) |

0.121(0.084) |

-0.039(0.076) |

| |

Unemployment |

-0.031(0.038) |

-0.069(0.074) |

0.001(0.073) |

| |

Others |

-0.071(0.074) |

0.02(0.087) |

-0.031(0.079) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.063**(0.41) |

-0.49(0.039) |

-0.73(0.028) |

| Const. |

0.082(0.082) |

0.061***(0.201) |

0.49***(0.211) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

0.385 |

0.155 |

0.286 |

Table 1.6 shows the regression result, which indicates the impact of total remittances in light of instrumental variables on financial inclusion in Bangladesh. However, Table 1.7 and Table 1.8 report the analysis of separately collected data on internal and international remittances respectively on financial inclusion. The two-stage least squares regression estimates come together with the results of the Linear Probability Model and Probit estimates. In fact, the two-stage least squares regression is more robust in that it dominates for prospective endogeneity between financial inclusion and remittance. The outcome further confirms that household remittances have a significant positive impact on the likelihood that household members will hold at least a bank account. Thus, it can be said that higher remittances provide extra cash to households for some time, which raises the demand for bank deposits, as financial establishments are considered safe places for households to keep their cash. These results are highly consistent with some recent studies [

14].

Table 1.6.

Total Remittance: Instrumental variable.

Table 1.6.

Total Remittance: Instrumental variable.

| |

Total Remittance |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.029***(0.011) |

-0.010(0.012) |

0.017*(0.011) |

| The Age of household head |

0.039***(0.002) |

0.039***(0.004) |

0.017***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.022**(0.007) |

0.021(0.008) |

0.001(0.007) |

| The Household head level of educational |

-0.001(0.001) |

-0.004**(0.003) |

-0.007***(0.003) |

| Female household head (%) |

0.000(0.001) |

-0.001*(0.002) |

-0.002*(0.002) |

| Destination |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

-0.042(0.041) |

0.022(0.0399) |

0.041(0.029) |

| |

Middle East |

-0.027(0.0371) |

0.0133**(0.044) |

0.037(0.072) |

| |

East Asia |

0.007(0.049) |

-0.081(0.071) |

-0.031(0.069) |

| |

Other countries |

0.071(0.081) |

0.051(0.211) |

0.013(0.074) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.231(0.024) |

-0.032(0.039) |

-0.024(0.039) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

0.211**(0.071) |

-0.067(0.074) |

0.055(0.066) |

| |

Student |

0.081(0.061) |

0.071(0.218) |

0.029(0.211) |

| |

Unemployment |

0.078(0.071) |

-0.127(0.088) |

0.071(0.067) |

| |

Others |

0.013(0.073) |

-0.044(0.211) |

0.063(0.101) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.127***(0.039) |

-0.031(0.59) |

-0.114**(0.0510 |

| Const. |

-0.112(0.129) |

0.701***(0.155) |

0.398***(0.192) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

0.316 |

0.193 |

0.273 |

| KP rk LM statistic (P-value) |

62.288 |

43.407 |

42.308 |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| CD Wald F statistic |

32.290 |

23.674 |

22.881 |

| Sargan stat. (p-value) |

11.725 |

8.919 |

0.775 |

| |

(0.001) |

(0.002) |

(0.401) |

The coefficient of remittance was also found to have a positive relationship with the probability of using mobile banking for a household's financial transactions. This outcome further ensures the recent findings using the Linear Probability Model and Probit estimates. However, the indicative migrant remittance coefficients point out that higher remittance increases the likelihood of a household using mobile banking. In fact, the coefficient of household remittances is not statistically positively significant when financial inclusion was proxied by the use of ATM cards. In fact, the coefficient of remittances is not important when financial inclusion is substituted by using ATM cards. This implies that remittances do not affect the probability of household members using ATM cards. An almost identical outcome was found in this case when the disaggregated migrant remittances were considered.

Table 1.7.

Internal Remittance: Instrumental variable.

Table 1.7.

Internal Remittance: Instrumental variable.

| |

Internal Remittance |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.041***(0.011) |

-0.012(0.023) |

0.028*(0.022) |

| The Age of household head |

0.039***(0.002) |

0.019***(0.004) |

0.021***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.025**(0.007) |

0.021(0.008) |

0.010(0.007) |

| The Household head level of educational |

-0.003(0.001) |

-0.004**(0.003) |

-0.007***(0.003) |

| Female household head (%) |

0.011(0.001) |

-0.003*(0.001) |

-0.002*(0.002) |

| Destination |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

-0.032(0.038) |

0.021(0.028) |

0.033(0.041) |

| |

Middle East |

-0.020(0.033) |

0.127**(0.049) |

0.049(0.072) |

| |

East Asia |

0.019(0.047) |

-0.092(0.071) |

-0.031(0.69) |

| |

Other countries |

0.071(0.081) |

0.051(0.219) |

0.027(0.074) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.021(0.024) |

-0.031(0.039) |

-0.26(0.034) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

0.133**(0.071) |

-0.066(0.075) |

0.046(0.068) |

| |

Student |

0.081(0.066) |

0.071(0.221) |

0.028(0.113) |

| |

Unemployment |

0.082(0.073) |

-0.211(0.088) |

0.062(0.066) |

| |

Others |

0.115(0.073) |

-0.434(0.221) |

0.064(0.101) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.218***(0.039) |

-0.014(0.049) |

-0.211**(0.039) |

| Const. |

-0.118(0.217) |

-0.615***(0.159) |

0.399***(0.168) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

0.329 |

0.157 |

0.283 |

| KP rk LM statistic (P-value) |

61.142 |

42.631 |

41.281 |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| CD Wald F statistic |

34.216 |

24.373 |

23.536 |

| Sargan stat. (p-value) |

11.812 |

8.413 |

0.601 |

| |

(0.001) |

(0.002) |

(0.398) |

Table 1.8.

International Remittance: Instrumental Variable Results.

Table 1.8.

International Remittance: Instrumental Variable Results.

| |

International Remittance |

| |

The household has a bank account |

Households use mobile banking |

Households use an ATM card |

| Remittance (Log) |

0.079***(0.031) |

-0.004(0.031) |

0.022*(0.021) |

| The Age of household head |

0.029***(0.003) |

0.032***(0.004) |

0.016***(0.003) |

| Number of household members |

0.007(0.007) |

0.010(0.008) |

0.001(0.008) |

| The Household head level of educational |

-0.003*(0.001) |

-0.007***(0.003) |

-0.007***(0.003) |

| Female household head (%) |

0.001(0.001) |

-0.001(0.001) |

-0.003*(0.001) |

| Destination of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

European countries |

-0.398***(0.139) |

0.039(0.201) |

-0.101(0.103) |

| |

Middle East |

-0.401***(0.104) |

0.144(0.108) |

-0.101(0.102) |

| |

East Asia |

-0.311**(0.100) |

-0.621(0.100) |

-0.104(0.111) |

| |

Other countries |

-0.319(0.138) |

0.0701(0.122) |

-0.124(0.122) |

| Employment status of migrants |

|

|

|

| |

Paid employment |

-0.003(0.0035) |

-0.031(0.039) |

-0.031(0.038) |

| |

Small-scale trade |

0.193**(0.064) |

-0.033(0.071) |

0.041(0.071) |

| |

Student |

0.073(0.082) |

0.0211(0.088) |

0.011(0.077) |

| |

Unemployment |

0.071(0.071) |

-0.087(0.075) |

0.041(0.069) |

| |

Others |

0.136(0.011) |

-0.010(0.111) |

0.071(0.110) |

| Gender (Female migrant) |

-0.188***(0.072) |

-0.030(0.049) |

-0.101**(0.049) |

| Const. |

0.149(0.109) |

0.489***(0.211) |

0.491***(0.163) |

| Rural |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| R-squared |

-0.109 |

0.152 |

0.189 |

| KP rk LM statistic (P-value) |

18.143 |

18.852 |

18.408 |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| CD Wald F statistic |

11.458 |

9.608 |

9.431 |

| Sargan stat. (p-value) |

3.128 |

9.511 |

0.311 |

| |

(0.0712) |

(0.0012) |

(0.627) |

Consistent with research assumptions, the migrant location in terms of the Middle East affects household financial inclusion. That is, migrant household members in the Middle Eastern region were more possible to use mobile banking than internal migrant households. Additionally, the number of adults member in a household increases the likelihood that a household holds a bank account. Nevertheless, the age of an adult member in a household increases the probability that a household member will hold a bank account, use ATM cards as well as use mobile banking. Furthermore, a student migrant in the households was more probably to hold a bank account. Notwithstanding, female migrants in the households were less likely to hold a bank account as well as use mobile banking, compared to male migrants in the households.

Table 1.9 presents the Propensity Score Matching analysis of the effect of remittance-receiving households on total remittance of financial inclusion. However, Table 1.10 reports the separate data analyses of internal and international remittances respectively using three matching algorithms such as nearest neighbor, stratification, and kernel matching. The matching algorithms provide immensely corresponding estimates of the impact of migrant household remittances on financial inclusion, the contradictory approach reveals that entire remittances significatively increase savings account provide by 11.8-13.7 percent. These outcomes delve out that migrant remittance-receiving households have a significant positive impact on financial inclusion. This result is quite consistent with the conclusions of previous studies on the impact of remittances on financial inclusion [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Table 1.9.

Total Remittances: Propensity Score Matching Results.

Table 1.9.

Total Remittances: Propensity Score Matching Results.

| Variables (Outcome) |

Matching algorithm |

ATET |

S.E |

t-test |

| The household has a bank account |

Nearest Neighbor |

0.137***

|

0.039 |

2.847 |

| The household has a bank account |

Kernel |

0.131***

|

0.029 |

2.369 |

| The household has a bank account |

Stratification |

0.118***

|

0.030 |

3.612 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Nearest Neighbor |

-0.082*

|

0.049 |

-1.623 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Kernel |

-0.002 |

0.038 |

-0.065 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Stratification |

0.006 |

0.037 |

0.191 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Nearest Neighbor |

-.0.88 |

0.071 |

-1.326 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Kernel |

-0.038 |

0.036 |

-1.101 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Stratification |

-0.049 |

0.049 |

-0.881 |

Table 1.10.

Internal and International Remittances: Propensity Score Matching Results.

Table 1.10.

Internal and International Remittances: Propensity Score Matching Results.

| Outcome variables |

Matching algorithm |

Remittance |

| |

|

Internal |

International |

| |

|

ATET |

S.E |

t-test |

ATET |

S.E |

t-test |

| The household has a bank account |

Nearest Neighbor |

0.131***

|

0.048 |

2.361 |

-0.002 |

0.041 |

-0.075 |

| The household has a bank account |

Kernel |

0.113***

|

0.031 |

2.851 |

0.029 |

0.028 |

1.166 |

| The household has a bank account |

Stratification |

0.118***

|

0.028 |

2.711 |

0.028 |

0.031 |

1.121 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Nearest Neighbor |

-0.082*

|

0.048 |

-1.568 |

-0.038 |

0.049 |

-1.178 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Kernel |

-0.002 |

0.039 |

-0.071 |

-0.073 |

0.049 |

-1.378 |

| Households use mobile banking |

Stratification |

0.006 |

0.041 |

0.125 |

-0.048 |

0.037 |

-1.255 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Nearest Neighbor |

-0.081 |

0.070 |

-1.445 |

-0.069 |

0.055 |

-1.226 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Kernel |

-0.036 |

0.035 |

-1.114 |

-0.065*

|

0.039 |

-1661 |

| Households use an ATM card |

Stratification |

-0.049 |

-0.49 |

-0.889 |

-0.071 |

0.038 |

-1.232 |

6. Conclusions

This paper seeks to understand the impacts of migrant remittances on the use of financial inclusion within households using the Migration and Remittance Household Survey in Bangladesh. Analyzing the results shows that the use of bank accounts in conventional financial management banks and mobile banking for receiving remittances and financial transactions among migrant households has increased. The use of ATM cards by households for financial transactions has not been significantly affected. The article explains that remittance-recipient households play an important role in strengthening financial inclusion in a country.

The significant positive relatedness between penetration to financial services and remittances attained from this paper may be implemented in the context of state policy decisions. For example, Bangladesh is one of the most remittance-dependent countries in the world, which has various barriers to receiving remittance practices. Despite the various costs and expenses associated with managing remittance receipts by remittance recipient households in Bangladesh may increase the likelihood of the role of financial inclusion in increasing the flow of remittances sent to the country through the formal channel.

References

- United Nations. Growth of international migration. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, 2022. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/desa/growth-international-migration-slowed-27-or-2-million-migrants-due-covid-19-says-un\.

- Lionell, R. Animated Chart: Remittance Flows and GDP Impact By Country. Visual Capitalist, 2023, January 25. Available at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/remittance-flows-gdp-impact-by-country/. 25 January.

- Ong, R. Remittances Grow 5% in 2022, Despite Global Headwinds. The World Bank, Press Release, 2022, November 30. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/11/30/remittances-grow-5-percent-2022. 30 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bank. Quarterly Report on Remittance Inflows in Bangladesh. ResearchDepartment, External Economics Wing, 2022, July-September. https://www.bb.org.bd/pub/quaterly/remittance_earnings/july-september_2022.pdf.

- Lucas, R.E.; Stark, O. Motivations to Remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy. 1985, 93, 901–918. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, H.; Docquier, F. The Economics of Migrants’ Remittances. In S. Kolm, and J. M. Ythier (Eds.). Handbook on the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity (Vol. 1). Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006.

- Ajefu, J. B. Migrant remittances and assets accumulation among Nigerian households. Migration and Development, 2018, 7(1), 72-84. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. International migration, remittances and household investment: Evidence from Philippine migrants. Exchange Rate Shock. Economic Journal, 2008, 118(528), 591–630. [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, C. Mexican Microenterprise Investment and Employment: The Role of Remittances. Integration and trade, 2007, 27, July–December. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Page, J. Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Development, 2005, 32, 1645–1669. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D.; Rapoport, H. Network Effects and the Dynamics of Migration and Inequality: Theory and Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 2007, 84(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Amuedo-Dorantes, C.; Tania, S.; Susana, P. Remittances and healthcare expenditure patterns of populations in origin communities: evidence from Mexico. INTAL-ITD Working Paper, 2007, 25.

- Acosta, P.; Fajnzylber, P.; Lopez, H. The Impact of Remittances on Poverty and Human Capital: Evidence from Latin American Household Surveys. International Remittances and the Household: Analysis and Review of Global Evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4247, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Anzoátegui, D.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Pería, M.S.M. Remittances and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from El Salvador. World Development, 2014, 54, 338-349. [CrossRef]

- Nyamongo, E.M.; Misati, R.N.; Kipyegon, L.; Ndirangu, L. Remittances, Financial Development, and Economic Growth in Africa. Journal of Economic and Business, 2012, 64, 240-260. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Peria, M.S.M. Do Remittances Promote Financial Development? Journal of Development Economics, 2011, 96(2), 255-264. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, C.; Cuecuecha, A. Remittances and the Use of Formal and Informal Financial Services. World Development, 2016, 77, 80-98. [CrossRef]

- Chami, R.; Fullenkamp, C. Workers’ Remittances and Economic Development: Realities and Possibilities, in Maximizing the Development Impact of Remittances. New York: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012.

- Orozco, M. International Financial Flows and Worker Remittances: Best practices. Report Commissioned by the Population and Mortality Division of the United Nations, 2004.

- Orozco, M.; Fedewa, R. Leveraging Efforts on Remittances and Financial Intermediation. INTAL-ITD: Inter-American Development Bank, 2006.

- Terry, D. F.; Wilson, S. R. Beyond Small Changes – Making Migrant Remittances Count, Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, 2005.

- https://socioeconomic.corona.gov.bd/economy/overseas-employment-and-remittance#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20World%20Bank,of%20remittance%20in%20South%20Asia.

- Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Expanding Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts. Review of Financial Studies, 2010, 23(1), 433–464. [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.; Khandker, S. The Impact of Group-Based Credit on Poor Households in Bangladesh: Does the Gender of Participants Matter? Journal of Political Economy, 1998, 106(5), 958–996. [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S. Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence using Panel Data from Bangladesh. World Bank Economic Review, 2005, 19(2), 263–286. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Glennerster, R.; Kinnan, C. The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. MIT Bureau for Research and Economic Analysis of Development Working Paper 278, 2010.

- Aportela, F. Effects of Financial Access on Savings by Low-income People. MIT Department of Economics Dissertation, 1999.

- Ashraf, N.; Aycinena, C.; Martinez, A.; Yang, D. Remittances and the Problem of Control: A Field experiment among migrants from El Salvador. Mimeo: University of Michigan, 2010.

- Dupas, P. , Robinson, J. Savings constraints and microenterprise development: Evidence from a field Experiment in Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2013, 5(1), 163-92. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.; Karlan, D.; Yin, W. Female Empowerment: Further Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines. World Development, 2010, 28(3), 333–344.

- Deodat, A. Financial development, international migrant remittances and endogenous growth in Ghana. Studies in Economics and Finance, 2011, 28(1), 68–89.

- Mundaca, D. Remittances, Financial Markets Development and Economic Growth: The Case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Review of Development Economics, 2009, 13(2), 288–303.

- Misati, R. N.; &, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Nyamongo, E. M. Financial Development and Private Investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and Business, 2011, 63(2), 139–151. [CrossRef]

- Cox-Edwards, A.; Ureta, M. International Migration, Remittances, and Schooling: Evidence from El Salvador. Journal of Development Economics, 2003, 72(2), 429–461. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. H.; Cuecuecha, A. Remittances, Household Expenditure and Investment in Guatemala. World Development, 2010, 38(11), 1626–1641. [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.; Parrado, E. International Migration and Business Formation in Mexico. Social Science Quarterly, 1998, 79(1), 1–20.

- Woodruff, C.; Zenteno, R. Migration Networks and Microenterprises in Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 2007, 82, PP. 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P. What is the Impact of International Remittances on Poverty and Inequality in Latin America? World Development, 2008, 36(1), 89–144.

- Osili, U.O. Migrants and Housing Investments: Theory and Evidence from Nigeria. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 2004, 52(4), 821-849. [CrossRef]

- Chami, R.; Jahjah, S.; Fullenkamp, C. Are immigrant remittance flows a source of capital for development? IMF Working Paper, WP/03/189, International Monetary Fund Institute, 2003.

- Ahlburg, D. Remittances and their impact: A study of Tonga and Western Samoa. Canberra: National Centre for Development Studies, Research School of Pacific Studies, the Australian National University, 1991.

- Brown, R. P. C.; Dennis, A.; Ahlburg, D. A. Remittances in the south pacific. International Journal of Social Economics, 1999, 6(1–3), 325–344.

- Ashraf, N.; Aycinena, D.’ Martınez, C.; Yang, D. Savings in Transnational Households: A field Experiment among Migrants from El Salvador. Review of Economics and Statistics, 2015, 97(2), 332–351. [CrossRef]

- Calero, C.; Bedi, A. S.; Sparrow, R. Remittances, Liquidity Constraints and Human Capital Investments in Ecuador. World Development, 2009, 37, 1143–1154. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E. J.; Wyatt, T. J. The Shadow Value of Migrant Remittances, Income and Inequality in a Household-Farm Economy. Journal of Development Studies, 1996, 32(6), 899–912.

- Ambrosius, C.; Cuecuecha, A. Are Remittances a Substitute for Credit? Carrying the Financial Burden of Health Shocks in National and Transnational Households. World Development, 2013, 46, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pattillo, C. A.; Wagh, S. ; Effect of Remittances on Poverty and Financial Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 2009, 37(1), 104–115. [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Lopez Cordova, E.; Martinez Perıa, M. S.; Woodruff, C. Remittances and Banking Sector Breadth and Depth. Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 2011, 95 (2), 229–241. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P. School Attendance, Child Labour, and Remittance from International Migration in El Salvador. The Journal of Development Studies, 2011, 47(6), 913-936.

- Rubin, D. B. Estimating Causal Effects of Treatments in Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 1974, 66, 688–701. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. R.; Rubin, D. B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 1983, 70(1), 41–55.

- Dehejia, R.; Wahba, S. Propensity Score-Matching Methods For Nonexperimental Causal Studies. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 2002, 84(1), 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M. Earnings and Employment Effects of Continuous Off-the-Job Training in East Germany after Unification. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 1999, 17(1), 74–90.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).