INTRODUCTION

The practice of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks has emerged as a major public health concern, particularly in developing countries. While self-medication itself is considered a form of self-care, its abuse through the indiscriminate use of natural products without professional guidance can have profound adverse health implications (Khatony et al., 2020; Owusu-Ofori et al., 2021). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-care as the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability, with or without the support of a healthcare provider (WHO, 2014). However, the subjective nature of self-care, influenced by diverse perceptions of health threats, has opened the door to potential abuse.

Self-medication entails the use of medicines or perceived medicinal products to treat or prevent self-identified diseases or symptoms without professional medical consultation or prescription (Tarciuc et al., 2020; Malik et al., 2020; Makowska et al., 2020). While self-medication, when done responsibly, can be an essential component of the healthcare system, it is often driven by self-perceptions, recommendations from non-professional sources, and media influences, leading to misinformation and the risk of abuse (Akande-Sholabi et al., 2021; Aslam et al., 2021; Wegbom et al., 2021).

Within the realm of self-medication, the abuse of natural products presents specific challenges. Natural product abuse involves the inappropriate use of medicinal substances derived from plants, animals, environmental, or microbial origins during self-medication, potentially leading to self-harm or adverse health effects. Throughout history, humans have explored natural products for food and medicine, initially with limited knowledge, leading to both beneficial and harmful outcomes, but in this way gathered relevant knowledge about their benefits and side effects (Chopra & Dhingra, 2021; Andrews & Johnson, 2020) which formed the basis for modern medicine. With the accumulation of knowledge and advancements in modern medicine and pharmacology, natural products have been integrated into complementary and alternative medicine practices (Atanasov et al., 2021; Tangkiatkumjai et al., 2020). However, the increasing availability and accessibility of natural products have raised concerns regarding their responsible use.

Disease outbreaks, such as the recent Covid-19 pandemic, have heightened anxiety and stress levels in the population, leading to an increased propensity for substance abuse, including self-medication with natural products (Panchal et al., 2020; Adger, 2021; Taylor, 2022). Disease outbreaks are characterized by an unexpected surge in new cases within defined geographical areas (epidemic) or widespread transmission across international borders (pandemic) (WHO, n.d.). As public panic ensues due to disease outbreaks, individuals resort to self-medication, seeking solace and protection from perceived threats through the use of various natural products.

Notably, self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks has been reported extensively in developing countries, with Asia, Africa, and Latin America experiencing a surge in such practices, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic (Feng et al., 2021; Liana & Phanumartwiwath, 2021; Anjorin et al., 2021; Bendezu-Quispe et al., 2022). The prevalence of natural product use during Covid-19 has been documented in several studies from different countries, emphasizing its widespread adoption (Nguyen et al., 2021; Parvizi et al., 2022; Umeta Chali et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022; Satyanarayana et al., 2023; Amuzie et al., 2022; Mphekgwana et al., 2021; AlNajrany et al., 2021; Guidos et al., 2022; Ayima et al., 2021).

The increased reliance on natural products for self-medication during disease outbreaks has raised concerns among global health organizations, such as the WHO, which cautions against unsubstantiated practices and emphasizes the need for evidence-based use of natural products (WHO, 2020). While there is potential for the efficacy of certain natural products, the lack of clinical trials and scientific evidence poses significant safety concerns.

This study aims to assess the implications of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks in developing countries. The objectives are to evaluate the state and quality of evidence in current literature, identify determinants and contributing factors to self-medication, analyse the risks and implications of such practices, and explore potential solutions to address this public health challenge. By shedding light on the impact of natural product use during disease outbreaks, this study seeks to inform policy decisions, promote responsible self-care practices, and safeguard public health in vulnerable populations across developing countries.

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) was used for documenting and reporting the review process together with screenshots of database search results. A Population, Exposure and Outcome (PEO) Framework (Moran et al., 2021) was used to formulate the study research question, which is: “What are the implications of self-medication with natural products (O) during disease outbreaks (E) among people in developing countries (P)?”

Data Sources

Relevant data were sourced via EBSCOHost from MEDLINE, The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Academic Search Complete and APA PsycINFO, Social Sciences Full Text (H.W. Wilson) and SocINDEX databases covering psychological, educational, social and health-related disciplines to ensure proper coverage. Being a modified systematic literature review, grey literature data were also sourced via Google scholar (Appendix section, Figure 2 and 3).

Search Strategy

A database search on EBSCOHost was conducted on 7th of March 2023, using Boolean operators and keywords derived from the research question to formulate a search strategy. The initial search strategy was “self-medication AND (natural products OR traditional medicine OR complementary OR alternative medicine OR herbal medicine) AND disease outbreaks AND developing countries” (Appendix section, Figure 4).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only articles published in English language between 2013-2033 were included. Articles related to alcohol, drug addiction, and substance abuse were excluded. Included articles met the following criteria: (1) addressed self-medication with at least one form of natural product; (2) within the geographical context of at least one developing country; and (3) in relation to a disease outbreak.

Study Selection

After manually identifying articles based on their titles from the search results, all relevant articles were collected, and their abstracts were evaluated for their alignment with the research question. Subsequently, those found to be relevant to the study were further assessed by reviewing their full texts to determine their suitability for inclusion in the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Management

From each article, four (4) topical themes were extracted in relation to self-medication with one or more forms of natural products in developing countries during a disease outbreak viz: (1) sources of natural products utilised (2) associated factors or determinants, (3) implications and (4) solutions. The following primary information were also extracted from each article: citation details, study location, study design, the prevalence of self-medication, disease outbreak, forms of natural products used and topical theme of the article. A preformulated digital data extraction form developed using a Microsoft word table was used to guide the retrieval, sorting and management of data from the included articles.

Quality and Bias Assessment

The quality and risk of bias of the included studies were assessed using the AXIS critical evaluation technique, based on criteria such as study objectives, design suitability, sample size, participant response rate, and internal consistency. Other factors evaluated included the justification of findings, acknowledgment of limitations, conflicts of interest/funding disclosure, and ethical considerations. Each study was scored using a checklist, where 'Yes' (1) indicated good quality and 'No' or 'Not Reported' (0) indicated otherwise. The final score out of 20 provided an insight into the overall study quality, enhancing the reliability and validity of the literature reviewed (Ayosanmi et al., 2022; Parvizi et al. (2023).

Data Analysis

Adopting a mixed method approach to analyse the extracted data, each article in this study was systematically assessed to identify, group, and compare any reoccurring themes whilst using descriptive statistics, a quantitative synthesis of the included research was carried out and results presented. Also, narrative synthesis was performed where the heterogeneous nature of the study data deterred any form of data pooling for quantitative synthesis (Carroll et al., 2020).

RESULTS

Study Selection

The initial search yielded a total of 1,683 publications, from which 453 duplicate records were removed yielding 1,230 articles. Manual title and abstract screening led to the removal of 857 articles as unrelated resulting in 373 articles, in which the full text of 38 articles was non-retrievable. Among the 335 articles thus assessed against the selection criteria, 117 articles were excluded as unrelated to any natural product use, 64 articles were outside the geographical context of developing countries, 98 articles were unrelated to disease outbreaks and 18 articles were not published in English resulting in 38 articles. After the review of full texts, 18 articles were excluded due to their study design (e.g., systematic literature reviews), resulting in the inclusion of 20 articles which were included in the final review, a PRISMA flowchart of the process is presented (Appendix section, Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

A total of 15,488 participants was recorded from the 20 selected articles of which 7.37% of the participants resorted to using at least one natural product for self-medication during a disease outbreak. The percentage utilisation of natural products per article ranged from 15.5% in an article with 97 participants (James et al., 2020) to 100% in an article with 16 participants (Mwangomilo, 2021). However, 2 articles did not quantify the number of participants' utilisation (Thebe, 2022 and Aprilio & Wilar, 2021) of a natural product. Among the 20 articles, 16 countries were captured including Kuwait, Mexico, Vietnam, Ghana, Saudi Arabia, China, Indonesia, Serbia, India, Turkey, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, and Ethiopia. Also, majority of the articles reported on Covid-19 (16 articles), HIV/Aids (2 articles) and Ebola (2 articles). Among these, the majority (14) articles were cross-sectional studies (Appendix section, Table 2) and Herbal medicines (13 articles) were the most reported (Appendix section, Table 1).

Study Quality and Bias Assessment

AXIS critical evaluation technique was used to assess the cross-sectional articles for quality and bias. Overall, 71.4% of the 14 articles accrued 15 or more points over the 20 points system in AXIS evaluation tool. The lowest score was 9 points by Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021 and the highest point recorded was 19 with 2 articles by Nguyen et al., 2021 and Amuzie et al., 2022. While majority (12) of the articles provided details regarding ethical approval and participants' consent before or during the studies (regarded as good practice), majority (9) of the articles did not report or describe the participants' response rate or put measures in place to address non-response rate, therefore signalling the possibility of response-bias in these studies (Appendix section, Table 3).

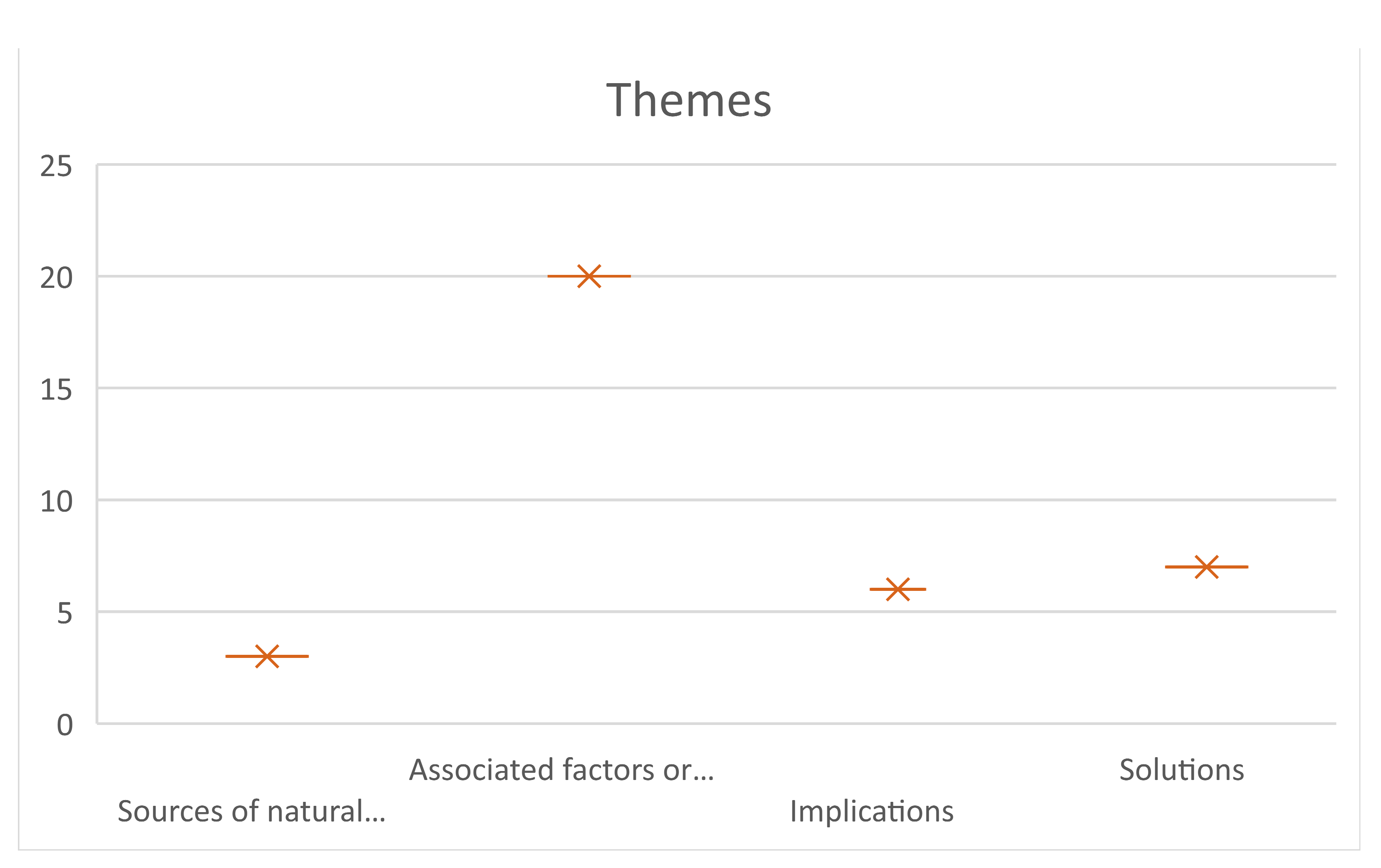

Themes

From the final 20 articles, 4 topical themes were extracted in relation to self-medication with one or more forms of natural products in developing countries during disease outbreaks. The most common theme was associated risk factors while themes such as the implications were under-reported (Appendix section, Figure 5).

Theme One: Sources

Theme One focused on the sources of natural products used during disease outbreaks. The most frequently mentioned sources were personal gardens, herbal drugstores, and traditional medicine hospitals or herbalists. Other sources included friends and relatives, public markets, and products ordered over the TV or Internet (Nguyen et al., 2021; Erarslan & Kültür, 2021; Tran et al., 2021).

Theme Two: Associated Factors or Determinants

Theme Two delved into the associated factors or determinants influencing the use of natural products. These factors were grouped into seven categories: demographic, personal, ideological, acquisitional, personal beliefs and opinions, external, and health-related factors. Demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, and urban dwelling significantly influenced natural product use (Alotiby et al., 2021; AlNajrany et al., 2021; Amuzie et al., 2022). Personal factors, including previous experiences and absence of health insurance, also played a role (Nguyen et al., 2021; Kristianto et al., 2022). Accessible, available, and affordable natural products were more likely to be used, representing the acquisition factors (Tran et al., 2021; Aprilio & Wilar, 2021; Tran et al., 2021). Ideological factors like religion and culture influenced people's beliefs and values regarding natural products (Shiferaw et al., 2020; James et al., 2020). Personal ideas and thoughts, such as the perception of efficacy and safety, were significant in promoting the use of natural products during disease outbreaks (Kretchy et al., 2022; Kültür, 2021; James et al., 2020; Hughes et al., 2012). External factors such as advice from family and friends, media influence, and non-availability of conventional medication also affected usage (Alotiby et al., 2021; Kretchy et al., 2022; James et al., 2020). Health-related factors, such as mental illness and the need for immune system boost, also influenced natural product use during disease outbreaks (James et al., 2020; Alonso-Castro et al., 2021; Kurniasih & Juwita, 2021).

Theme Three: Implications

Theme Three explored the implications of using natural products during disease outbreaks. The common implications of natural products used during disease outbreaks include Diarrhoea, Stomach pain, Sweating, Headache, and Nausea/vomiting (Alonso-Castro et al., 2021; Alotiby et al., 2021; Kurniasih & Juwita, 2021). These side effects are typically mild and self-limiting and may not require medical attention in most cases. Others include Drowsiness, Dizziness, Hunger, Fatigue/tiredness, Coughing and Sneezing. Severe conditions include Anxiety, Tremors, Insomnia, Hallucinations, Anger, Depression, Gastritis, Constipation, Hypotension, Hyperglycaemia, Itching, difficulty in breathing, and unexplained effects (Alonso-Castro et al., 2021; Thebe, 2022; Alotiby et al., 2021; Kurniasih & Juwita, 2021). Other issues found were higher frequency and severity of symptoms (Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021), interaction with other medication (Aprilio & Wilar, 2021) and less communication with physicians (Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021). One study by Nuertey et al., 2022 shows that steam inhalation and herbal baths increased the risk of COVID-19 infection.

Theme Four: Solutions

Theme Four discussed proposed solutions to address self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks. Public enlightenment and health education campaigns were suggested to raise awareness about the potential risks and benefits of using natural products (AlNajrany et al., 2021; Aprilio & Wilar, 2021; James et al., 2020). Researchers recommended further investigation and standardization of natural products to ensure their safety and efficacy (Kretchy et al., 2022). Incorporating local wisdom through ethnomedicine was also advised to enhance health promotion and education (Aprilio & Wilar, 2021).

DISCUSSION

Self-medication with natural products is a human behaviour which poses a major public health challenge across several countries. The practise holds significant health implications, especially when used during times of disease outbreaks characterised by fear, anxiety, depression, and irrational thinking. The findings from this study reveals the focus of current literature on the factors and determinants of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks with little attention being paid to investigating the implications of the practise.

While it is important to acknowledge the determinants of the behaviour, it is very paramount that the implications are made known and given public attention to help give voice to those possibly affected and suffering in silence. This is reflected in one of the findings in this review by Ismail & Al Hashel (2021) that participants who practised self-medication with natural products during the Covid-19 pandemic were withdrawn and had less communication with their physicians, as such and by extension, possible side effects could not have been reported. According to Vickers et al. (2006), participants in their study claimed to refrain from reporting the side effects of their herbal medicine use to their doctors due to the negative response they might get in return. However, no newer study was found to corroborate this claim. On the other hand, when appropriately considered, this could account for the current paucity of reports in the literature on the implications of natural products used during the pandemic.

In this review, one identified contributory factor to self-medication with natural products during the pandemic is the presence of several conspiracy theories about Covid-19 vaccines (Thebe, 2022). While this presents as a contributory factor, by extension this stands as an implication of self-medication with natural products in the form of vaccine hesitancy. A study by Kabakama et al., 2022 titled ‘Commentary on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa’ reported that in some countries such as Cameroon, Uganda, Sierra Leone and Tanzania, herbal medicine and steam inhalation is considered a more protective and curative alternative to vaccination due to discrepancies and misconceptions associated with the vaccination programme in these countries.

Regarding steam inhalation for preventing and treating Covid-19 in some developing countries, one study in this review by Nuertey et al., 2022 shows that steam inhalation and herbal baths increased the risk of COVID-19 infection. While the study did not report the possible reason for this finding, it reported that subgroup analyses of some home remedies for Covid-19 such as herbal steam inhalation and herbal baths were associated with an increased risk of Covid-19 infection (95% CI = 6.10–116.24 and 95% CI = 0.49–14.78 respectively). While steam inhalation is shown to increase the risk of Covid-19, a more worrying aspect of this practice is steam burns. A study by Brewster et al. (2020) titled ‘Steam inhalation and paediatric burns during the COVID-19 pandemic’ shows that there was a 30% increase in the number of scalds resulting from steam inhalation in children as presented at the Birmingham Children's Hospital, in the UK.

Furthermore, within the context of this review, another discernible factor contributing to self-medication practices with natural products during disease outbreaks is the purported aim of fortifying the immune system against the virulent disease (James et al., 2020; Kurniasih & Juwita, 2021; Kladar et al., 2022). While this may seem rational, the act of self-medication with natural products could paradoxically engender a false sense of safety, potentially exacerbating the spread of the disease.

Moreso, home remedies played a major role in the utilisation of natural products during disease outbreaks, this is fostered by persistent farming where personal gardening is identified as a reoccurring factor that encourages self-medication with natural products in this review. This is directly linked with the identified acquisition factors such as ease of accessibility, availability, and affordability (Nguyen et al., 2021), which in turn pose a considerable challenge for regulatory efforts by the government and health agencies in several developing countries (Adebisi et al., 2022) exacerbated by ideological factors such as religion (Kristianto et al., 2022), culture and tradition (Aprilio & Wilar, 2021).

In addition, demographic factors were identified in the majority (14) of the articles reviewed. While this is not shocking as demographic factors have a proven association with health behaviour in literature (Zajacova et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2021), the review showed some interesting findings. For example, females were found to self-medicate with natural products more than the male (Alonso-Castro et al., 2021; Kretchy et al., 2022; AlNajrany et al., 2021; Nuertey et al., 2022; Erarslan & Kültür, 2021; James et al., 2020; Shiferaw et al., 2020). The literature presents several reasons for these findings, Al-Hussaini et al. (2014) study in Kuwait showed that the female sex is more likely to self-medicate because, since their teenage age, they are used to self-medication for menstrual pains. Concerning the Covid-19 pandemic, Heemskerk et al. (2022) observed in their study that the female sex is more likely to feel more at risk of Covid-19 than their male counterparts. In this vein, Coman et al. (2022) posit that the female sex is more likely to seek social media guidance and follow through with advice from digital media. Moreover, this review repeatedly sighted the influence of social media as a contributor to self-medication with natural products during the pandemic (Alotiby et al., 2021; Kretchy et al., 2022; Nuertey et al., 2022).

A seemingly interesting finding from the review is the higher prevalence of self-medication with natural products during the pandemic in urban areas than in rural areas. However, on careful examination, one would find that most of the studies were conducted via the internet as online surveys. With limited internet connectivity in rural areas, more participants' responses would be from urban areas, creating a form of selection bias (Lehdonvirta et al., 2021). While age did not show any significant difference with natural product use, young adults were more likely to self-medicate with natural products (Hughes et al., 2021). However, being married and having children are two significant factors which influenced the use of natural products during the pandemic (Nguyen et al., 2021; Nuertey et al., 2022; Kristianto et al., 2022; Kladar et al., 2022; James et al., 2020; Hughes et al., 2021). A study by Tugume & Nyakoojo (2019) indicates that married couples and parents are driven to herbal medicine to protect their families due to a sense of duty and responsibility.

Findings from this review show that the major side effects of self-medication with natural products are Diarrhoea, Stomach pain, Sweating, Headache, and Nausea/vomiting according to Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 and Alotiby et al., 2021. It is worth noting that these are among the enlisted symptoms of drugs including herbal remedies overdose according to the Department of Health, Government of Australia (Department of Health, Australia 2021). The issue of overdose with natural products is ubiquitously reported in the literature, especially about herbal and traditional medicine which is probably because most herbal and traditional medicines especially home remedies lack appropriate dosage indications (Zhou et al., 2019).

According to Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 in this review, diarrhoea is a common side effect of many natural products used for self-medication, and it can be caused by a variety of factors. Some herbs, such as aloe vera and senna, have laxative effects that can cause diarrhoea (Ashfaq & Yousaf, 2022). Alotiby et al., 2021 identified Stomach pain in this review as a major side effect of herbal medicine use, particularly if the herbs are taken on an empty stomach or in large amounts, a finding corroborated by Tripathi & Bahuguna (2022). Sweating, headache, and nausea/vomiting are other common side effects of natural products cited in this review by Alonso-Castro et al., 2021, Alotiby et al., 2021 and Kurniasih & Juwita (2021). These side effects may be due to the active ingredients in the herbs or to an allergic reaction (Suntar, 2020). In this review, Kurniasih & Juwita (2021) observed some natural products can interact with other medications, so it is important to consult with a healthcare provider before using any herbal remedies, particularly when taking other medications (Nugraha et al., 2020).

Severe side effects of natural product use can be a cause for concern and may require immediate medical attention. For example, in this review a study by Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 identified anxiety and tremors, as common symptoms of an adverse reaction to some herbs, and in some cases, these symptoms can be severe enough to require hospitalization. Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 also identified insomnia, hallucinations, and depression as other severe side effects that can be caused by herbal medicines, especially if they are taken in high doses or used improperly (Tripathi & Bahuguna, 2022). Another study in this review by Aprilio & Wilar (2021) observed that It's important to note that some herbs can interact with prescription medications, leading to severe side effects, such as hypotension, hyperglycemia, and constipation, a finding corroborated by Kim et al., 2021. Also in this review, Kurniasih & Juwita (2021) observed that herbs can also cause itching and breathing difficulties, which can be dangerous for people with asthma or other respiratory conditions. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that even natural remedies can have side effects and can be toxic if taken improperly or in excess.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Like any research, this study has certain limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the systematic review included a limited number of articles, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. While there is no universal consensus on the minimum sample size for systematic literature reviews, future research should aim to include a more extensive range of relevant studies to enhance the robustness of the conclusions. Additionally, half of the assessed articles relied on online surveys, which may not fully represent the actual population under study. The potential for bias exists due to the lack of reporting or addressing non-response rates in some studies employed for this review, potentially impacting the overall significance of the findings.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study aimed to investigate the implications of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks in developing countries. The findings indicate that self-medication with natural products is a prevalent practice, with herbal medicine being the most commonly used form of self-medication. Despite limited research on the topic, the identified common side effects of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks include diarrhoea, stomach pain, sweating, headache, and nausea/vomiting, among others. Notably, individuals who self-medicate tend to experience more frequent and severe disease symptoms, and interactions with other medications may lead to adverse effects. One concerning finding is that certain practices, such as steam inhalation and herbal baths, were associated with increased COVID-19 infection risk.

The study also revealed that people who self-medicate with natural products tend to withdraw and had less communication with their physicians, thereby hampering the report of side effects to their doctors, which by extension might account for the current paucity of reports on the implications of the practise in the literature. In the same vein, the study posits the possibility of individuals suffering in silence from the impact of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks such as the recent Covid-19 pandemic. The study highlights various factors which influence the practice of self-medication with natural products, including demographic, personal, ideological, acquisitional, external, and health-related factors. Among these, ideological and acquisitional factors exert the strongest influence.

In a nutshell, this study sheds light on the implications of self-medication with natural products during disease outbreaks, emphasizing the need for better awareness and understanding of this practice and its potential to cause self-harm and potentially exacerbate the spread of the prevailing disease. Individuals who self-medicate may not report the negative implications due to fear of judgment and reactions from others including healthcare workers. It is crucial to foster an environment that enhances open communication and encourages help-seeking without prejudice or stigmatization. Additionally, while the regulation of natural products is essential, promoting evidence-based herbal medicine and fostering research to isolate active medicinal components can contribute to safer and more effective usage. By stimulating further research, particularly qualitative studies, the study encourages individuals to share their experiences, thereby informing public health policies and interventions in this domain.

Funding

There was no funding received for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Gratitude is extended to my dissertation supervisor, Chris Smith, for his invaluable guidance and support. Thanks to Andrea Jane Evans of the UCLAN Library Support Team for literature search assistance, and to Christopher Bell of the UCLAN EAP and Academic Skills Development Team for his tremendous preliminary support and guidance towards my dissertation. Sincere appreciation also goes to the contributing authors, whose valuable research and insights have shaped the content and findings presented here.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Declares no competing or conflicting interests.

Appendix

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing study selection protocol.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing study selection protocol.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Google scholar search results.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Google scholar search results.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of EBSCOHost search results.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of EBSCOHost search results.

Figure 4.

Screenshot of Keywords and EBSCOHost database search strategy.

Figure 4.

Screenshot of Keywords and EBSCOHost database search strategy.

Figure 5.

Extraction of themes.

Figure 5.

Extraction of themes.

Table 1.

Data Extraction Table.

Table 1.

Data Extraction Table.

| S/N |

Author and Year |

Study Location |

Disease Outbreak |

Natural Products |

Source |

Factors or Determinants |

Implications |

Solutions |

Prevalence Data (Per Participants) |

| S1 |

Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021). |

Kuwait |

COVID-19 |

HM

|

NR |

Worsening of headaches,

Inadequate quality of medical care,

Psychosocial stressors |

Higher frequency and severity of migraine, Less compliance to treatment, Less communication with physicians

|

Neurological intervention |

39.9% of 1018 |

| S2 |

Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 |

Mexico |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Advice from friends

Determinants

Female, Low education, Unmarried, Unemployment, No health insurance, Mental illness |

Drowsiness, Dizziness, Fatigue/tiredness, Nausea/vomiting, Headache, Anxiety, Tremors, Insomnia, Hallucinations, Anger, Depression, Hunger, Diarrheal, Gastritis, Stomach pain, Sweating |

Public health campaigns |

61% of 2100 |

| S3 |

Nguyen et al., 2021 |

Vietnam |

COVID-19 |

HM |

Personal garden, Markets, Herbal drug stores |

Factors

Previous personal experiences, considered natural, Ease of access, Availability, Advice from family.

Determinants

Married, Urban dwelling, medium income, perception of health status |

NR |

NR |

49% of 508 |

| S4 |

Alotiby et al., 2021 |

Saudi Arabia |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Social media, Family/ friends influence, Previous positive experience, published articles, Health care staff, Internet (YouTube/ google)

Determinants

Socio-demographic factors, Age |

Diarrhoea, Abdominal pain, Constipation, Headache, Hypotension, Hyperglycaemia |

NR |

92.7% of 1054 |

| S5 |

Kretchy et al., 2022 |

Ghana |

COVID-19 |

CAM |

NR |

Factors

Strong belief of efficacy, Deemed Safe,

Self-decided, Media (e.g., TV, Radio, Newspapers), Friends/Relatives, social media, Internet

Determinants

Female, Having children, Covid-19 status |

NR |

Public health policy,

Clinically validated CAM treatments,

isolating lead herbal compounds by pharmaceutical companies |

82.5% of 1195 |

| S6 |

AlNajrany et al., 2021 |

Saudi Arabia |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Coping with stress

Determinants

Female, Age increase by 10 years, Unemployment, Comorbidities,

On prescription medication, Higher education |

NR |

Public awareness campaigns |

64% of 1473 |

| S7 |

Kurniasih & Juwita (2021) |

Indonesia |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Considered safe,

From nature, used over generations, Boost Immune system |

itching,

nausea,

vomiting,

unexplained effects |

NR |

83% of 68 |

| S8 |

Aprilio & Wilar, (2021). |

Africa,

India,

China |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Considered safe,

From nature,

Easier Access

Cultural values

|

Interaction with other medication |

Appropriating health education to a society’s particular

Culture.

Local wisdom through ethnomedicine should work in health promotion and education |

NR |

| S9 |

Nuertey et al., 2022 |

Ghana |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Social media, Family/ friends, Previous use

Determinants

Younger people, Married, Female

|

Steam inhalation and herbal baths increased risk of COVID-19 infection.

|

NR |

29.6% of 882 |

| S10 |

Kristianto et al., 2022 |

Indonesia |

COVID-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Magical health beliefs, holistic health belief, knowledge, and attitudes

Determinants

Young adults, Religion (Muslim), Married,

Higher Education, High Income, Urban dwelling, Having Insurance, High perceived risk of having COVID-19 |

NR |

NR |

62% of 1621 |

| S11 |

Kladar et al., 2022 |

Serbia |

COVID-19 |

CAM |

NR |

Factors

Expected effects on immune and respiratory system, populistic thematic literature, Internet.

Determinants

Younger people (21-35), Higher education, Employed, Higher income,

Married

|

NR |

NR |

23.24% of 1704 |

| S12 |

Mwangomilo, 2021 |

Tanzania |

COVID-19 |

TM |

NR |

Factors

Natural origin of traditional medicines,

Approval of traditional medicine,

Preservation and duration of expiration of some traditional medicines,

Cost of preparation and time,

Use of traditional medicine,

|

NR |

promote proper use of traditional medicine |

100% 0f 16 |

| S13 |

Erarslan & Kültür (2021) |

Turkey |

COVID-19 |

HM |

Herbalist

Pharmacist

Friends-relatives

TV,

Internet |

Factors

Safety, Efficacy, Recognition, Recommendation of friends-relatives,

Price

Determinants

Female,

Being a healthcare professional, Housewives, Having a Covid-19

positive family member |

NR |

NR |

54.4% of 871 |

| S14 |

Tran et al., 2021 |

Vietnam |

COVID-19 |

HM |

Home gardens,

herbal drugstores

traditional medicine hospital |

Factors

A natural source of medicine,

Having positive previous personal experience, Being used it before pandemic, Ease of accessibility, Availability

Determinants

Education, marital status, self-perception of health status |

NR |

NR |

46.8 % of 787 |

| S15 |

Amuzie et al., 2022 |

Nigeria |

Covid-19 |

HM |

|

Factors

Family members influence, Fear of isolation, Fear of stigmatization,

Doctor, Colleagues, Internet, Fear of infection, Death of a colleague, friend or family member, Media

Determinants

Older age, Lower educational status,

Perception to cost |

|

|

43.7% of 469 |

| S16 |

Thebe, 2022 |

Zimbabwe |

Covid-19 |

HM |

NR |

Factors

desire, need, fear, suffering, strain, pain, illness, hospitals considered a death sentence, mistrust of western medicines and institutions, conspiracies theories about vaccines and COVID-19,

need to pursue livelihood despite the pandemic |

coughing,

sneezing,

difficulty in breathing |

NR |

NR |

| S17 |

James et al., 2020 |

Sierra Leone |

Ebola |

T&CM |

NR |

Factors

Immune booster, Personal experience of efficacy, Low side effects, a holistic approach to health, easier to talk to a T&CM practitioner.

Determinants

Adult age (34-49), Female,

Secondary education, Muslim,

Married, Middle Income, Urban dwelling,

Low perception about one health,

Absence of a chronic disease |

NR |

Public education,

practitioner–survivors communication

promoting regulation and research |

45.5% of 358 |

| S18 |

James et al., 2020 |

Sierra Leone |

Ebola |

T&CM |

NR |

Health system factors

Non-availability of drugs at the health care facilities, Negative attitude of healthcare providers and other patients,

Perceived ineffectiveness of conventional medicine, Long distance from the health facility

Patient factors

Unaffordability of drugs at the health care facilities, Previous positive experience with T&CM use, Adherence to traditional practices, |

NR |

NR |

100% of 41 |

| S19 |

Hughes et al., 2012 |

South Africa |

HIV/AIDS |

TM |

NR |

Factors

Self, Family/Friends, Previous use of TM,

Perceived efficacy,

Determinants

Adults (38-62), Rural, No schooling,

Unmarried, Employed, Have a source of income, No health insurance,

|

NR |

NR |

15.5% of 97 |

| S20 |

Shiferaw et al., 2020 |

Ethiopia |

HIV/AIDS |

HM |

NR |

Factors

Wanting personal control over health, Reduced side-effects, improved general wellbeing, Family, Culture, Tradition

Determinants

Age (above 60), Female, Having side-effects from antiretroviral therapy (ART)

|

NR |

NR |

37.35% of 318 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Assessment Parameters |

Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021 |

Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 |

Nguyen et al., 2021 |

Alotiby et al., 2021 |

Kretchy et al., 2022 |

AlNajrany et al., 2021 |

Kurniasih & Juwita (2021) |

Aprilio & Wilar, (2021) |

Nuertey et al., 2022 |

Kristianto et al., 2022 |

Kladar et al., 2022 |

Mwangomilo, 2021 |

Erarslan & Kültür (2021) |

Tran et al., 2021 |

Amuzie et al., 2022 |

Thebe, 2022 |

James et al., 2020 |

James et al., 2020 |

Hughes et al., 2012 |

Shiferaw et al., 2020 |

TOTAL |

| |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

C6 |

S7 |

S8 |

S9 |

S10 |

S11 |

S12 |

S13 |

S14 |

S15 |

C16 |

S17 |

S18 |

S19 |

S20 |

|

| |

|

| Data type |

| Primary |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

19 |

| Secondary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| |

| Article Type |

| Published (Journal) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

19 |

| Unpublished (Dissertation) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| |

| Study type |

| Quantitative |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

|

|

Y |

Y |

15 |

| Qualitative |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

|

4 |

| Mixed method |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| |

| Method |

| Cross sectional study |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

|

Y |

Y |

|

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

|

|

Y |

Y |

14 |

| Case control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Literature review |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| In depth Interviews |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

2 |

| Narrative Synthesis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Focused Group Discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

1 |

| |

Table 3.

Quality and Bias Assessment of Included Articles.

Table 3.

Quality and Bias Assessment of Included Articles.

| Assessment Parameters |

Ismail & Al Hashel, 2021 |

Alonso-Castro et al., 2021 |

Nguyen et al., 2021 |

Alotiby et al., 2021 |

Kretchy et al., 2022 |

AlNajrany et al., 2021 |

Kurniasih & Juwita (2021) |

Aprilio & Wilar, (2021) |

Nuertey et al., 2022 |

Kristianto et al., 2022 |

Kladar et al., 2022 |

Mwangomilo, 2021 |

Erarslan & Kültür (2021) |

Tran et al., 2021 |

Amuzie et al., 2022 |

Thebe, 2022 |

James et al., 2020 |

James et al., 2020 |

Hughes et al., 2012 |

Shiferaw et al., 2020 |

|

| |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S6 |

S7 |

S8 |

S9 |

S10 |

S11 |

S12 |

S13 |

S14 |

S15 |

S16 |

S17 |

S18 |

S19 |

S20 |

|

| |

Introduction |

| 1. Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

YG |

YG |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| |

Methods |

| 2. Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 3. Was the sample size justified? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

NA |

NA |

N |

N |

NA |

N |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

N |

Y |

|

| 4. Was the target/reference population clearly defined? (Is it clear who the research was about?) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 5. Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? |

NR |

NR |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

NA |

NA |

Y |

N |

NA |

NR |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 6. Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? |

NR |

NR |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

NA |

NA |

Y |

N |

NA |

NR |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 7. Were measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders? |

NR |

Y |

Y |

NR |

Y |

Y |

NR |

NA |

NA |

NR |

NR |

NA |

NR |

NR |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NR |

NR

|

|

| 8. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NR |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 9. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialled, piloted or published previously? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

N |

N |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 10. Is it clear what was used to determine statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (e.g.,p values, CIs) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NR |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

N |

Y |

|

| 11. Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

Result

12. Were the basic data adequately described? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 13. Did the response rate not raise concerns about non-response bias? |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

NA |

NA |

N |

N |

NA |

N |

N |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

N |

N |

|

| 14. If appropriate, was information about non-responders described? |

N |

N |

Y

|

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

NA |

NA |

N |

NR |

NA |

N |

N |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NR |

N |

|

| 15. Were the results internally consistent? ALPHA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 16. Were the results for the analyses, as described in the methods, presented? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

|

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| |

Discussion |

| 17. Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by the results? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| 18. Were the limitations of the study discussed? |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

N |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| |

Others |

| 19. Was there information about any funding sources or conflicts of interest and/or how it may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results? |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

NA |

NA |

N |

Y |

NA |

NR |

N |

N |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

N |

|

| 20. Was ethical approval or consent of participants attained? |

NR |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

NA |

Y |

Y |

Y |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Y |

Y |

|

| |

Score |

| Aggregate risk of bias rating |

9/20 |

17/20 |

19/20 |

15/20 |

17/20 |

17/20 |

10/20 |

NA |

NA |

15/20 |

14/20 |

NA |

10/20 |

15/20 |

19/20 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

15/20 |

16/20 |

|

| Questionnaire administration |

OFF |

OFF |

ON |

ON |

ON |

OFF |

ON |

NA |

NA |

OFF |

ON |

NA |

ON |

ON |

OFF |

NA |

NA |

NA |

OFF |

|

|

References

- Adebisi, Y.A.; Nwogu, I.B.; Alaran, A.J.; Badmos, A.O.; Bamgboye, A.O.; Rufai, B.O.; Okonji, O.C.; Malik, M.O.; Teibo, J.O.; Abdalla, S.F.; et al. Revisiting the issue of access to medicines in Africa: Challenges and recommendations. Public Heal. Challenges 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, H. Alcohol and Other Drug Use and Abuse in Adolescents. 2021; 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, O.; Gautam, L.; Simkhada, P.; Hall, S. Prevalence, determinants and knowledge about herbal medicine and non-hospital utilisation in southwest Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajibo, H. T. , Chukwu, N. E., & Okoye, U. U. (2020). COVID-19, lockdown experiences and the role of social workers in cushioning the effect in Nigeria. Journal of Social Work in Developing Societies, 2(2) 6-13.

- Ajibola, O.; Omisakin, O.A.; Eze, A.A.; Omoleke, S.A. Self-Medication with Antibiotics, Attitude and Knowledge of Antibiotic Resistance among Community Residents and Undergraduate Students in Northwest Nigeria. Diseases 2018, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akande-Sholabi, W.; Ajamu, A.T.; Adisa, R. Prevalence, knowledge and perception of self-medication practice among undergraduate healthcare students. J. Pharm. Policy Pr. 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, M.; Mustafa, S.; Ali, S. Self-medication among undergraduate medical students in Kuwait with reference to the role of the pharmacist. J. Res. Pharm. Pr. 2014, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlNajrany, S.M.; Asiri, Y.; Sales, I.; AlRuthia, Y. The Commonly Utilized Natural Products during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Ruiz-Padilla, A.J.; Ortiz-Cortes, M.; Carranza, E.; Ramírez-Morales, M.A.; Escutia-Gutiérrez, R.; Ruiz-Noa, Y.; Zapata-Morales, J.R. Self-treatment and adverse reactions with herbal products for treating symptoms associated with anxiety and depression in adults from the central-western region of Mexico during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 272, 113952–113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotiby, A. The Impact of Media on Public Health Awareness Concerning the Use of Natural Remedies Against the COVID-19 Outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, ume 14, 3145–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotiby, A.A.; Al-Harbi, L.N. Prevalence of using herbs and natural products as a protective measure during the COVID-19 pandemic among the Saudi population: an online cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y. M. (2020). Self-medication. In Drug safety in developing countries (pp. 73-86). Academic Press.

- Amuzie, C.I.; Kalu, K.U.; Izuka, M.; Nwamoh, U.N.; Emma-Ukaegbu, U.; Odini, F.; Metu, K.; Ozurumba, C.; Okedo-Alex, I.N. Prevalence, pattern and predictors of self-medication for COVID-19 among residents in Umuahia, Abia State, Southeast Nigeria: policy and public health implications. J. Pharm. Policy Pr. 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjorin, A.; Abioye, A.; Asowata, O.; Soipe, A.; Kazeem, M.; Adesanya, I.; Raji, M.; Adesanya, M.; Oke, F.; Lawal, F.; et al. Comorbidities and the COVID-19 pandemic dynamics in Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2020, 26, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilio, K.; Wilar, G. Emergence of Ethnomedical COVID-19 Treatment: A Literature Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, ume 14, 4277–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M. H. , & Yousaf, M. (2022). Antifungal Activity of Senna alata–A Review. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 12(4), 307-311.

- Aslam, A.; Gajdács, M.; Zin, C.S.; Ab Rahman, N.S.; Ahmed, S.I.; Zafar, M.Z.; Jamshed, S. Evidence of the Practice of Self-Medication with Antibiotics among the Lay Public in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayosanmi, O.S.; Alli, B.Y.; Akingbule, O.A.; Alaga, A.H.; Perepelkin, J.; Marjorie, D.; Sansgiry, S.S.; Taylor, J. Prevalence and Correlates of Self-Medication Practices for Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Benites-Meza, J.K.; Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Uyen-Cateriano, A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Toro-Huamanchumo, C.J.; Hernandez, A.V.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Consumption of Herbal Supplements or Homeopathic Remedies to Prevent COVID-19 and Intention of Vaccination for COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, C.T.; Choong, J.; Thomas, C.; Wilson, D.; Moiemen, N. Steam inhalation and paediatric burns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1690–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, P.; Chesser, M.; Lyons, P. Air Source Heat Pumps field studies: A systematic literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorge, N.W.; Zahn, M.V.; Belot, M.; Broek-Altenburg, E.v.D.; Choi, S.; Jamison, J.C.; Tripodi, E. Socio-demographic factors associated with self-protecting behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Popul. Econ. 2021, 34, 691–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, B.; Dhingra, A.K. Natural products: A lead for drug discovery and development. Phytotherapy Res. 2021, 35, 4660–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Huang, F.; Zhang, M.; Huang, B.; Wang, Y. Current status of traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of COVID-19 in China. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, E.; Coman, C.; Repanovici, A.; Baritz, M.; Kovacs, A.; Tomozeiu, A.M.; Barbu, S.; Toderici, O. Does Sustainable Consumption Matter? The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Medication Use in Brasov, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erarslan, Z. B. , & Kültür, Ş. A cross-sectional survey of herbal remedy taking to prevent Covid-19 in Turkey. Journal of Research in Pharmacy 2021, 25, 920–936. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhriati, F.; Yusuf, C.F. Religious Traditional Treatment of Epidemics: A Legacy From Acehnese Manuscripts. Anal. 2020, 5, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Yang, J.; Xu, M.; Lin, R.; Yang, H.; Lai, L.; Wang, Y.; Wahner-Roedler, D.L.; Zhou, X.; Shin, K.-M.; et al. Dietary supplements and herbal medicine for COVID-19: A systematic review of randomized control trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 44, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, M.; Le Tourneau, F.-M.; Hiwat, H.; Cairo, H.; Pratley, P. In a life full of risks, COVID-19 makes little difference. Responses to COVID-19 among mobile migrants in gold mining areas in Suriname and French Guiana. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114747–114747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, H. T. (2020). Some home remedies for hair loss. International journal of scientific & technology research. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9(1), 1914-1917.

- Huang, J.; Tao, G.; Liu, J.; Cai, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, J.-X. Current Prevention of COVID-19: Natural Products and Herbal Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 588508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Puoane, T.; Clark, B.; Wondwossen, T.; Johnson, Q.; Folk, W. Prevalence and Predictors of Traditional Medicine Utilization Among Persons Living With Aids (PLWA) on Antiretroviral (ARV) and Prophylaxis Treatment in Both Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 9, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Al Hashel, J. Use of traditional medicine in treatment of migraine during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic- an online survey. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 429, 119337–119337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.B.; Wardle, J.; Steel, A.; Adams, J. Ebola survivors’ healthcare-seeking experiences and preferences of conventional, complementary and traditional medicine use: A qualitative exploratory study in Sierra Leone. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pr. 2020, 39, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Wardle, J.; Steel, A.; Adams, J.; Bah, A.J.; Sevalie, S. Additional file 1 of Traditional and complementary medicine use among Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone: a qualitative exploratory study of the perspectives of healthcare workers providing care to Ebola survivors. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Wardle, J.; Steel, A.; Adams, J. Experiences and preferences of conventional, complementary and traditional medicine use among Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone. Adv. Integr. Med. 2019, 6, S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatony, A.; Soroush, A.; Andayeshgar, B.; Abdi, A. Nursing students’ perceived consequences of self-medication: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Park, J.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Yu, Y.J.; Kim, J.E.; Lim, S.C. A Study on Safety and Drug Interactions of Herbal Drugs that Compose 100 Herbals Medication Prescriptions. Yakhak Hoeji 2021, 65, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladar, N.; Bijelić, K.; Gatarić, B.; Pajić, N.B.; Hitl, M. Phytotherapy and Dietotherapy of COVID-19—An Online Survey Results from Central Part of Balkan Peninsula. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretchy, I.A.; Boadu, J.A.; Kretchy, J.-P.; Agyabeng, K.; Passah, A.A.; Koduah, A.; Opuni, K.F. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine for the prevention of COVID-19 infection in Ghana: A national cross-sectional online survey. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristianto, H. , Pramesona, B. A., Rosyad, Y. S., Andriani, L., Putri, T. A. R. K., & Rias, Y. A. (2022). The effects of beliefs, knowledge, and attitude on herbal medicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Indonesia. F1000Research, 11, 483-493.

- Kristianto, H. , Pramesona, B. A., Rosyad, Y. S., Andriani, L., Putri, T. A. R. K., & Rias, Y. A. (2022). The effects of beliefs, knowledge, and attitude on herbal medicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Indonesia. F1000Research, 11, (2) 483-495.

- Kurniasih, T. R. , & Juwita, F. I. (2021). The Use of Herbal Medicine Among Sleman Residents during COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications, 4, (5) 78-81, 2021.

- Lam, C.S.; Koon, H.K.; Chung, V.C.-H.; Cheung, Y.T. A public survey of traditional, complementary and integrative medicine use during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0253890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V. , Oksanen, A., Räsänen, P., & Blank, G. (2021). Social media, web, and panel surveys: using non-probability samples in social and policy research. Policy & Internet, 13(1), 134-155.

- Liana, D. , & Phanumartwiwath, A. (2021). Leveraging knowledge of Asian herbal medicine and its active compounds as COVID-19 treatment and prevention. Journal of Natural Medicines, 1-18.

- Lin, L. T. , Hsu, W. C. ( 4(1), 24–35.

- Liu, J.; Manheimer, E.; Shi, Y.; Gluud, C. Chinese Herbal Medicine for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2004, 10, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, M. , Boguszewski, R., Nowakowski, M., & Podkowińska, M. (2020). Self-medication-related behaviors and Poland’s COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8344.

- Malik, M.; Tahir, M.J.; Jabbar, R.; Ahmed, A.; Hussain, R. Self-medication during Covid-19 pandemic: challenges and opportunities. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, M. , Odette, D. U. M. A., Gheorma, A., Manole, A., Pavaleanu, I., Velenciuc, N., & Duceac, L. D. (2017). Self-medication-a public health problem in Romania nowadays. The first quests. The Medical-Surgical Journal, 121(3), 608-615.

- Moran, S. , Bailey, M., & Doody, O. (2021). An integrative review to identify how nurses practicing in inpatient specialist palliative care units uphold the values of nursing. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 1-16.

- Mwangomilo, F. G. (2021). Community perceptions on the use of traditional medicines for management of covid-19 in Ilala. (Doctoral Dissertation, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences). http://dspace.muhas.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/3007.

- Nguyen, P.H.; De Tran, V.; Pham, D.T.; Dao, T.N.P.; Dewey, R.S. Use of and attitudes towards herbal medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Vietnam. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 44, 101328–101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuertey, B.D.; Addai, J.; Kyei-Bafour, P.; Bimpong, K.A.; Adongo, V.; Boateng, L.; Mumuni, K.; Dam, K.M.; Udofia, E.A.; Seneadza, N.A.H.; et al. Home-Based Remedies to Prevent COVID-19-Associated Risk of Infection, Admission, Severe Disease, and Death: A Nested Case-Control Study. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraha, R.V.; Ridwansyah, H.; Ghozali, M.; Khairani, A.F.; Atik, N. Traditional Herbal Medicine Candidates as Complementary Treatments for COVID-19: A Review of Their Mechanisms, Pros and Cons. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Ofori, A.K.; Darko, E.; Danquah, C.A.; Agyarko-Poku, T.; Buabeng, K.O. Self-Medication and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Survey of Students Studying Healthcare Programmes at a Tertiary Institution in Ghana. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, N. , Kamal, R., Orgera, K., Cox, C., Garfield, R., Hamel, L., & Chidambaram, P. (2020). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://pameladwilson.com/wp-content/uploads/4_5-2021-The-Implications-of-COVID-19-for-Mental-Health-and-Substance-Use-_-KFF-1.pdf.

- Parvizi, A.; Haddadi, S.; Vajargah, P.G.; Mollaei, A.; Firooz, M.; Hosseini, S.J.; Takasi, P.; Farzan, R.; Karkhah, S. A systematic review of life satisfaction and related factors among burns patients. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 2830–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, A.; Baye, A.M.; Amogne, W.; Feyissa, M. Herbal Medicine Use and Determinant Factors Among HIV/AIDS Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS - Res. Palliat. Care 2020, ume 12, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süntar, I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: role of medicinal plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 19, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangkiatkumjai, M.; Boardman, H.; Walker, D.-M. Potential factors that influence usage of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide: a systematic review. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarciuc, P.; Stanescu, A.M.A.; Diaconu, C.C.; Paduraru, L.; Duduciuc, A.; Diaconescu, S. Patterns and Factors Associated with Self-Medication among the Pediatric Population in Romania. Medicina 2020, 56, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. (2022). The psychology of pandemics. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 581-609.

- Thebe, P. Home Remedies as Agency in the Face of COVID-19 in Zimbabwe. Orient. Anthr. A Bi-annual Int. J. Sci. Man 2022, 22, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.D.; Tran, V.D.; Pham, D.T.; Cao, T.T.N.; Bahlol, M.; Dewey, R.S.; Le, M.H.; A Nguyen, V. Perspectives on COVID-19 prevention and treatment using herbal medicine in Vietnam: A cross-sectional study. . 2021, 34, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P. , & Bahuguna, Y. (2022). A review on herbal gargles. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 11 (5) 396-404.

- Tugume, P.; Nyakoojo, C. Ethno-pharmacological survey of herbal remedies used in the treatment of paediatric diseases in Buhunga parish, Rukungiri District, Uganda. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Vickers, K.; Jolly, K.B.; Greenfield, S.M. Herbal medicine: women's views, knowledge and interaction with doctors: a qualitative study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 6, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegbom, A.I.; Edet, C.K.; Raimi, O.; Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Kiri, V.A. Self-Medication Practices and Associated Factors in the Prevention and/or Treatment of COVID-19 Virus: A Population-Based Survey in Nigeria. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9, 606801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (n.d.). Disease outbreaks. https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/disease-outbreaks/index.html.

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO supports scientifically-proven traditional medicine. https://www.afro.who-supports-scientifically-proven-traditional-medicine.

- WHO Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine. (accessed on). Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine#tab=tab_1.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2014). Self care for health. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/205887. 1066.

- Zajacova, A.; Jehn, A.; Stackhouse, M.; Denice, P.; Ramos, H. Changes in health behaviours during early COVID-19 and socio-demographic disparities: a cross-sectional analysis. Can. J. Public Heal. 2020, 111, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, C.-G.; Chang, D.; Bensoussan, A. Current Status and Major Challenges to the Safety and Efficacy Presented by Chinese Herbal Medicine. Medicines 2019, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).