Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Significance of the Study

1.3. Literature Review

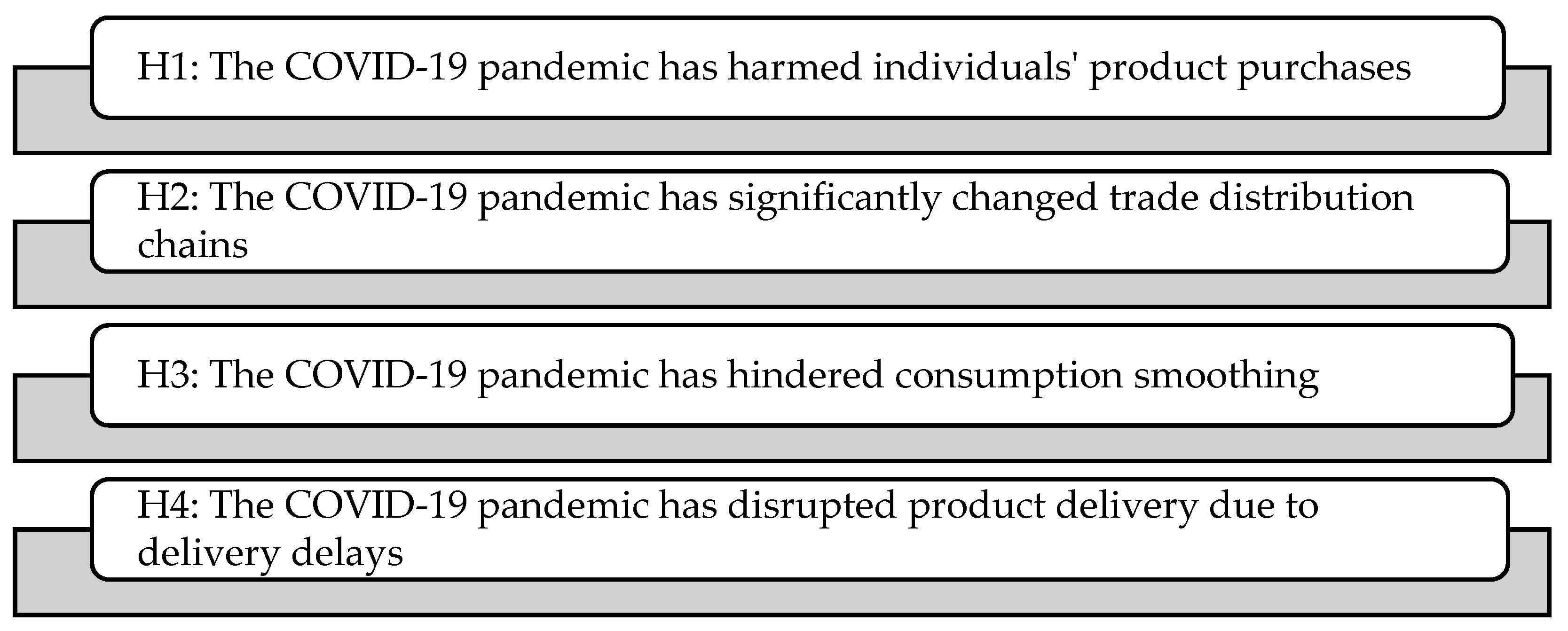

1.4. Research objectives and hypothesis

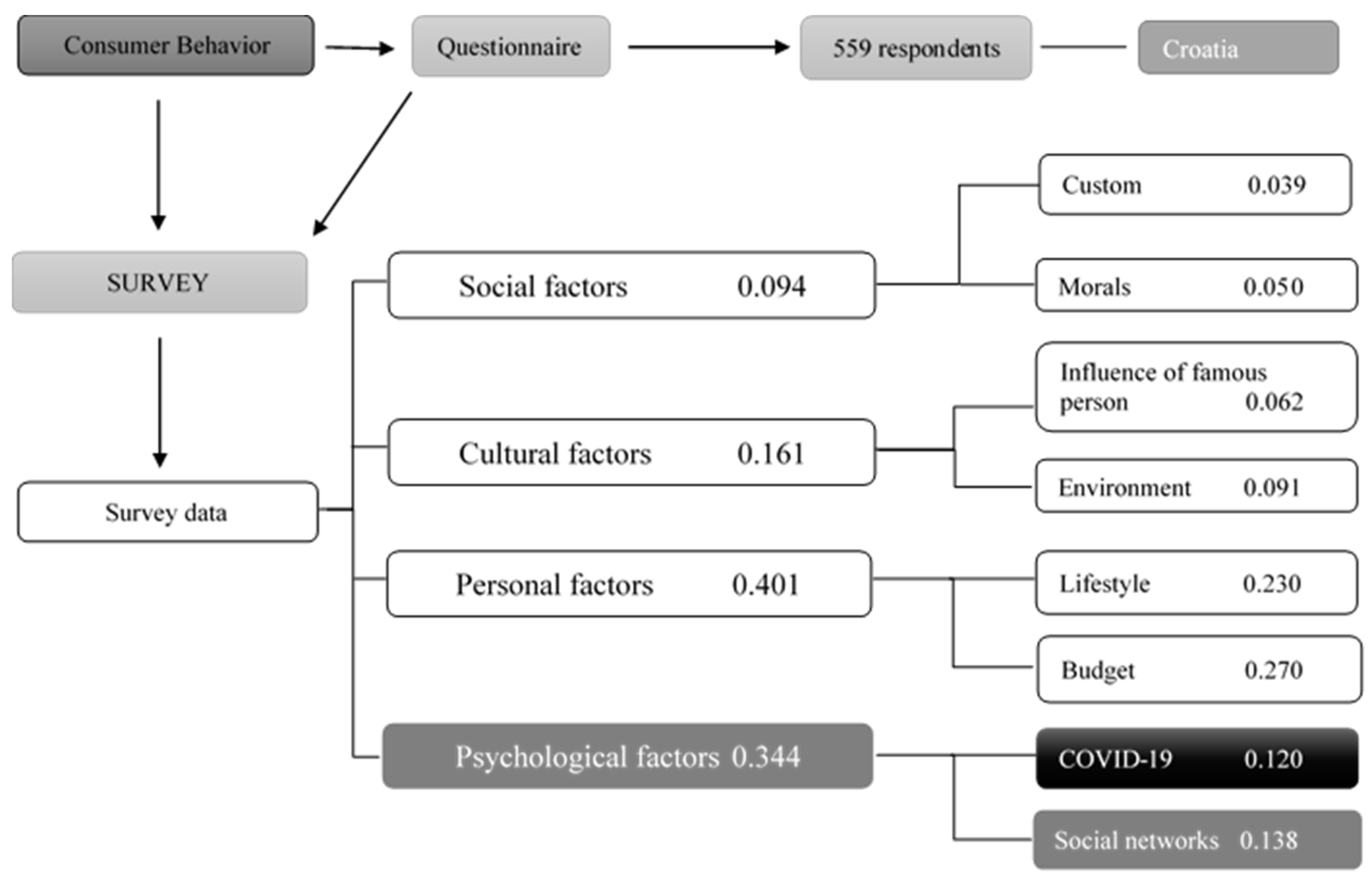

2. Materials and Methods

- Unity.

- Complexity.

- Interdependence.

- Hierarchic structure.

- Measurement.

- Consistency.

- Synthesis.

- Tradeoffs.

- Judgement and Consensus.

- Process Repetition.

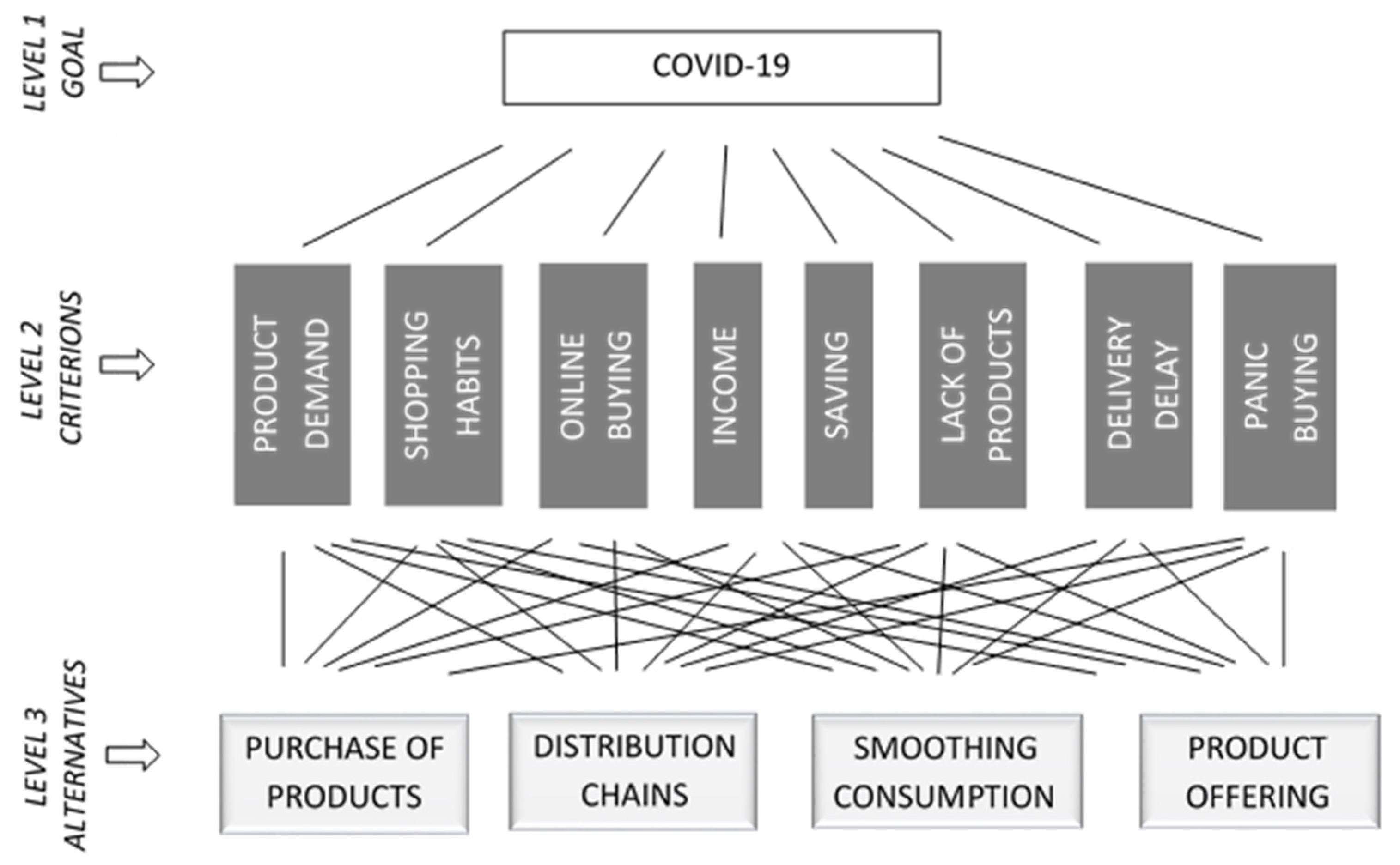

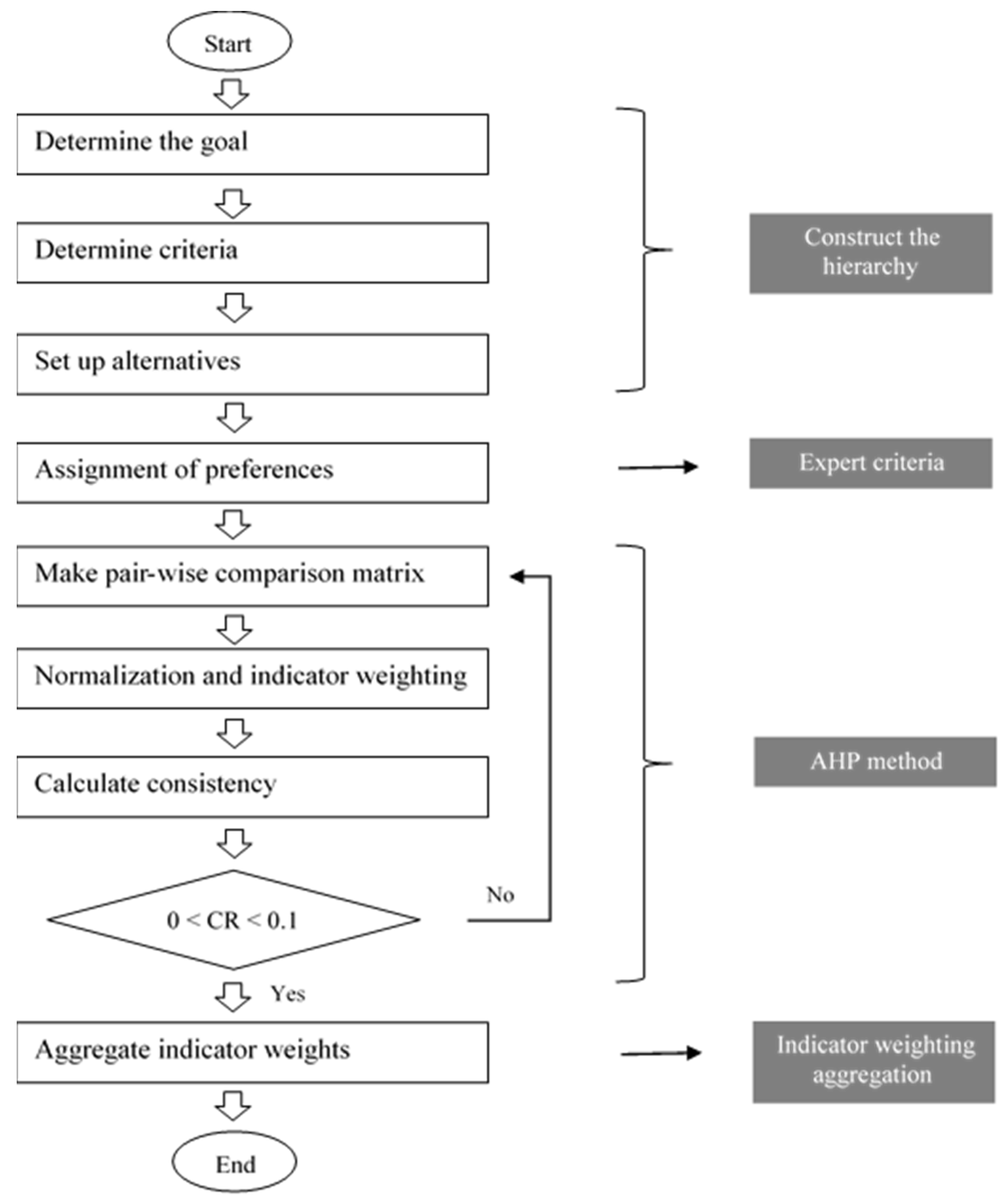

2.1. Modelling the AHP hierarchic structure

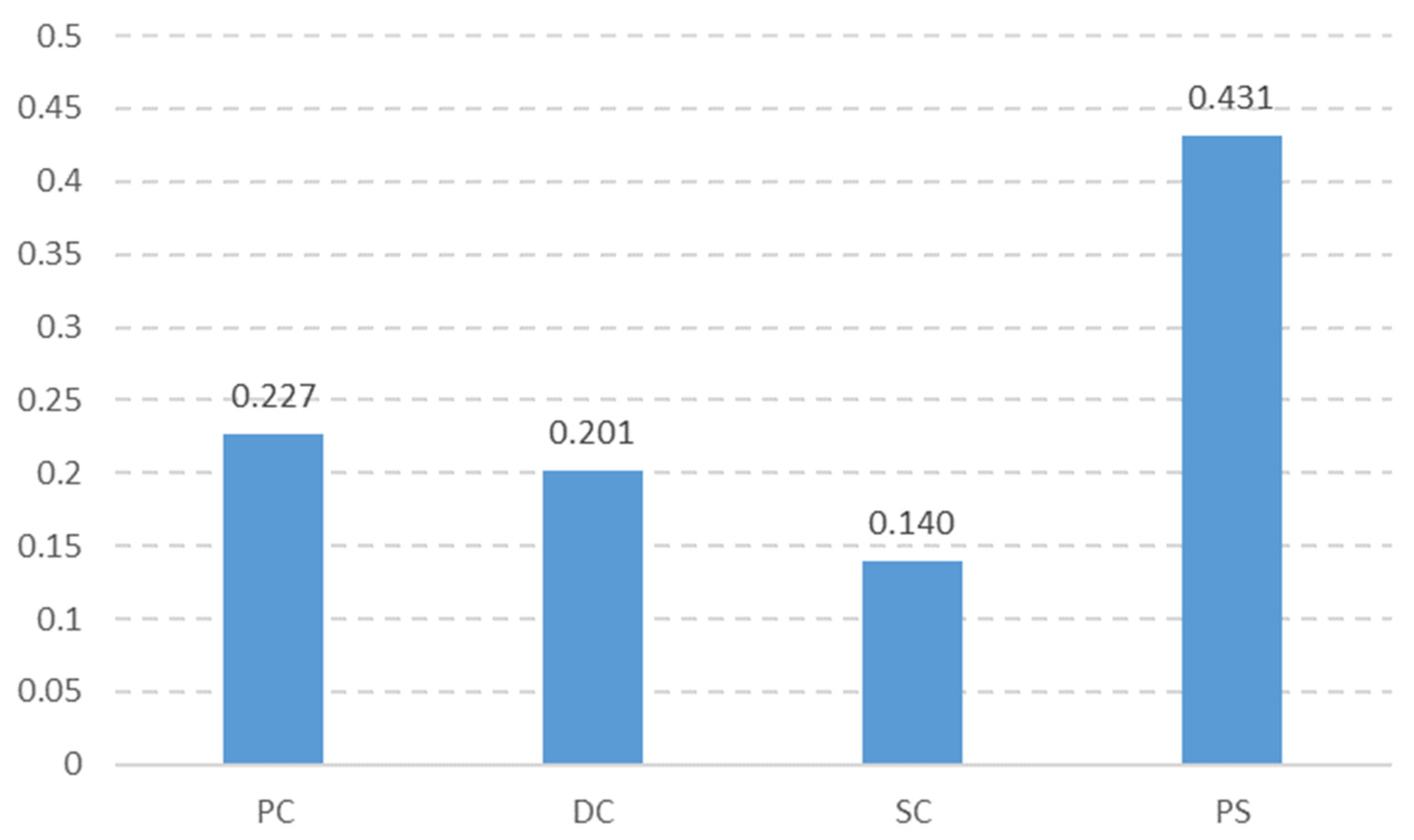

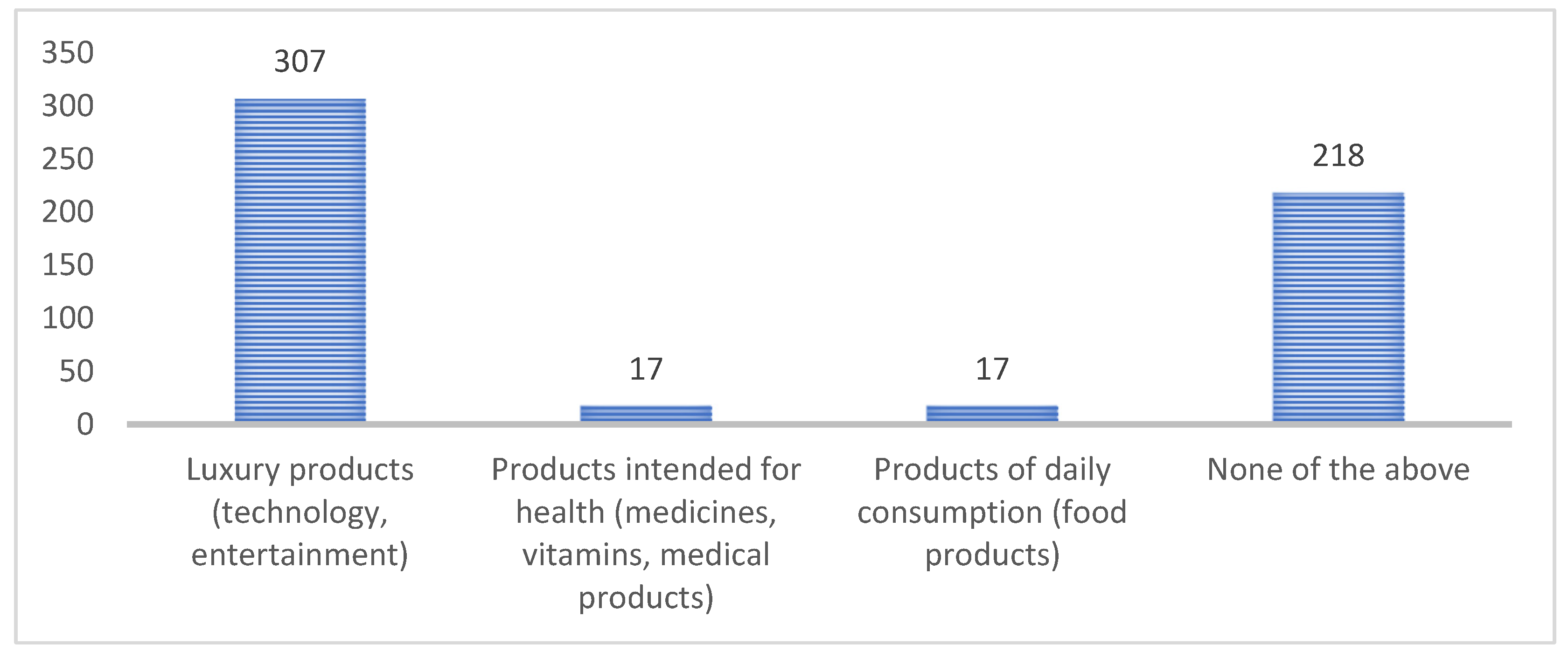

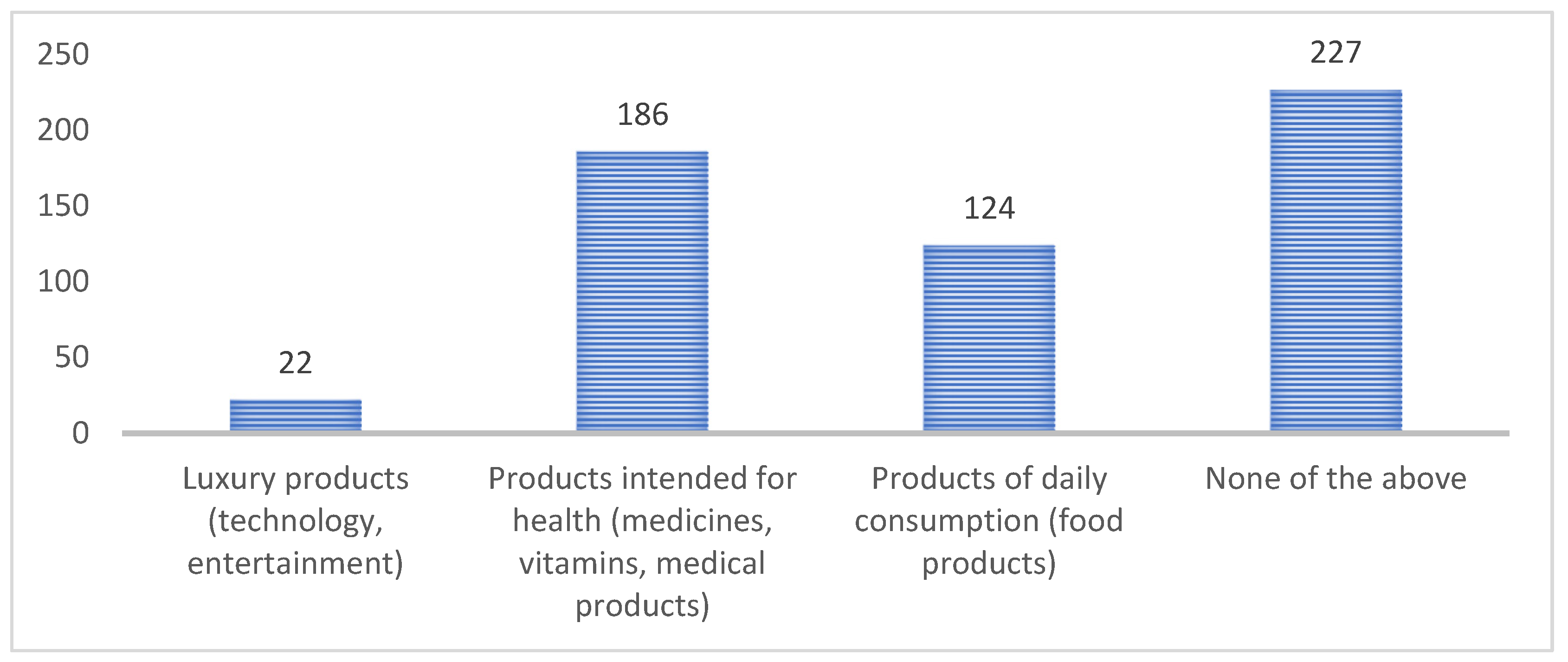

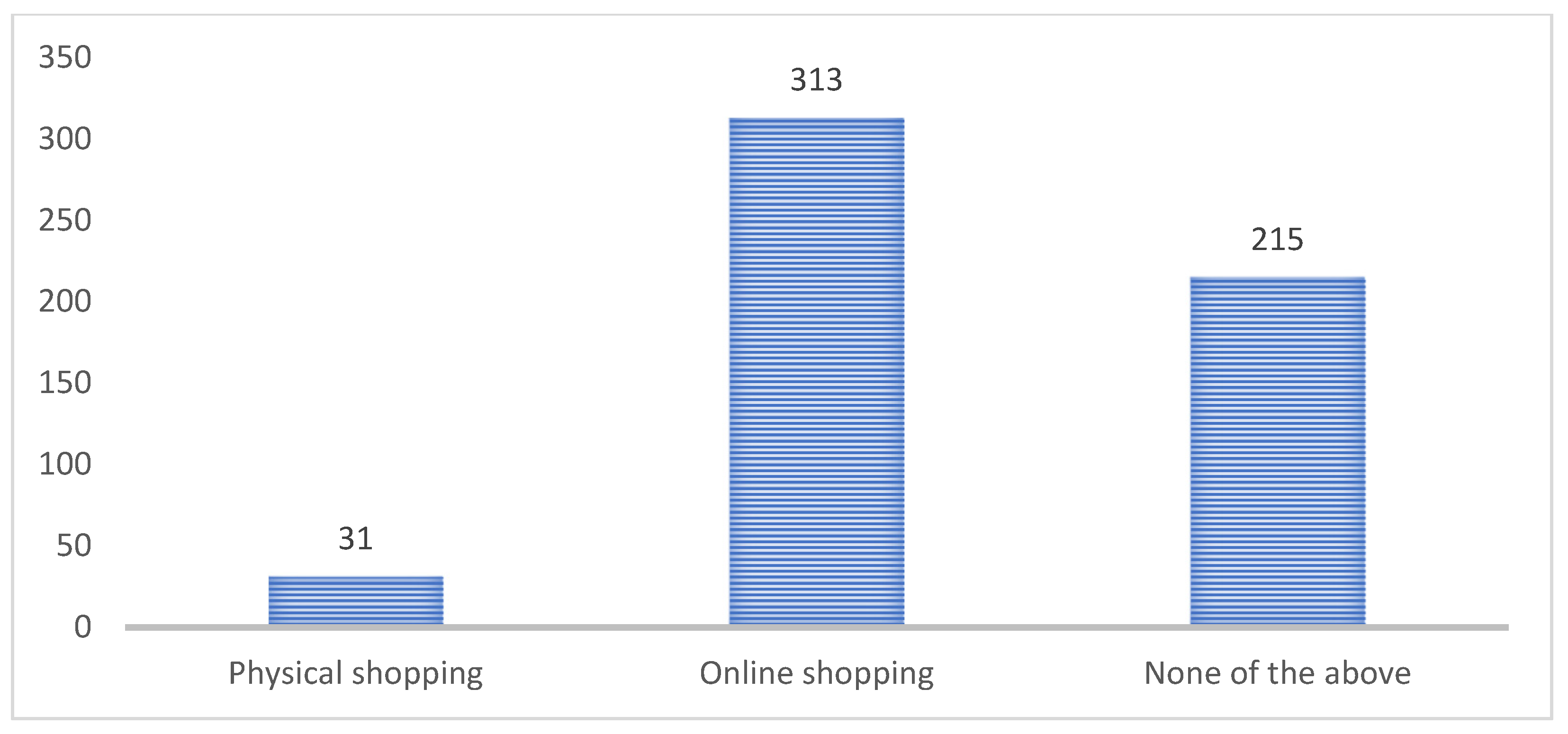

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- World Health Organization. Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide.

- Kohli, S.; Timelin, B.; Fabius, V.; Veranen, M. S. How COVID-19 is changing consumer behavior - now and forever. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/how%20covid%2019%20is%20changing%20consumer%20behavior%20now%20and%20forever/how-covid-19-is-changing-consumer-behaviornow-and-forever.pdf.

- Monitor Deloitte. Impact of COVID-19 on short- and medium-term consumer behavior: Will the crisis have a lasting effect on consumption? Monitor Deloitte, 2020, 6. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/sk/Documents/consumer-business/Impact_of_the_COVID-19_crisis_on_consumer_behavior.pdf.

- KPMG International Limited. COVID-19 is changing consumer behavior worldwide; business needs to adapt rapidly. KPMG. 2020. Available online: https://kpmg.com/ro/en/home/media/press-releases/2020/12/covid-19-is-changing-consumer-behavior-worldwide---business-need.html.

- Statista. Coronavirus: impact on the retail industry worldwide - Statistics & Facts. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/6239/coronavirus-impact-on-the-retail-industry-worldwide/#editorsPicks.

- D'Arpizio, C.; Levato, F.; Fenili, S.; Colacchio, F.; Prete, F. Luxury after Covid-19: Changed for (the) Good? Bain & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/luxury-after-coronavirus/.

- Euromonitor International. Top 10 Global Consumer Trends 2022. Euromonitor International. 2022. Available online: https://go.euromonitor.com/white-paper-EC-2022-Top-10-Global-Consumer-Trends.html?utm_campaign=CT_WP_20_01_14_Top_10_GCT_2020_EN&utm_medium=Website&utm_source=Landing-Page.

- International Monetary Fund. The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression. Press Release. 2020, 20(98). Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/23/pr2098-imf-managing-director-statement-following-a-g20-ministerial-call-on-the-coronavirus-emergency.

- United Nations. COVID-19 and E-commerce: A Global Review. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2020. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtlstict2020d13_en.pdf.

- Šostar, Marko, Chandrasekharan, H. Arunchand, Rakušić, Ivana. Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Sales, Vallis Aurea – 8th International Conference, 2022, 451-459. Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr:8443/1262599.

- Šostar M, Ristanović V. Assessment of Influencing Factors on Consumer Behavior Using the AHP Model. Sustainability. 2023, 15(13), 10341. [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. L. An eigenvalue allocation model for prioritization and planning. Working paper, Energy Management and Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 1972.

- Saaty, T. L. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. Journal of mathematical psychology. 1977, 15(3), 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. L. The analytic hierarchy process. McGraw-Hill, New York. 1980.

- Saaty, T. L. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World. RWS Publications, Pittsburgh. 2008.

- Salem, O.; Salman, B.; Ghorai, S. Accelerating Construction of Roadway Bridges Using Alternative Techniques and Procurement Methods. Transport 2017, 33, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurík, L.; Horňáková, N.; Šantavá, E.; Cagáňová, D.; Sablik, J. Application of AHP method for project selection in the context of sustainable development. Wireless Networks 2020, 28, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzal-Dec, D.J.; Zwolińska-Ligaj, M.A. How to Deal with Crisis? Place Attachment as a Factor of Resilience of Urban–Rural Communes in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M.; Pourmadadkar, M.; Ardestani, A.; Ghadamgahi, S.; Yang, H. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Shopping and Travel Behaviour: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, A., Leone, D. and Caporuscio, A. Changes in the post-covid-19 consumers’ behaviors and lifestyle in italy. A disaster management perspective. Italian Journal Marketing 2022, 87–106. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.; Mahroof Khan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Hashmi, M.S.; Khan, M.M.; Hishan, S.S. Post-COVID 19 Tourism: Will Digital Tourism Replace Mass Tourism? Sustainability, 2021, 13, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R. Y. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumers: Preparing for Digital Sales in IEEE. Engineering Management Review, 2020, 48(3), 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Hajizada, S.; Kovalyova, I.; Sakhbieva, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. Journal of Theoretical Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2021, 16, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H.; Meyerhoefer D. C. Covid-19 and the Demand for Online Food Shopping Services: Empirical Evidence from Taiwan. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2020, 103(2), 448–465. [CrossRef]

- Rahmanov. F., Mursalov. M., Rosokhata, A. Consumer behavior in digital era: impact of COVID-19. Marketing and Management of Innovations 2021, 2, 243–251.

- Tran, N. T. A; Nguyen, D. H. A.; Ngo, M. V. and Nguyen, H. H. Explaining consumers’ channel-switching behavior in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Cogent Business & Management 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B. J. Impact of COVID-19 on consumer buying behavior toward online shopping in Iraq. Economic Studies Journal 2020, 18(42), 267–280. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3729323.

- Pham, K. V.; Do Thi, H. T. and Ha Le, H. T. study on the COVID-19 awareness affecting the consumer perceived benefits of online shopping in Vietnam. Cogent Business and Management, 2020, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Saleem, A.; Saeed, W.; Ul Haq, J. Online Consumer Satisfaction During COVID-19: Perspective of a Developing Country. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Zhang, D. The Impact of Consumer Purchase Behavior Changes on the Business Model Design of Consumer Services Companies Over the Course of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milaković Kursan, I. Purchase experience during the COVID-19 pandemic and social cognitive theory: The relevance of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability for purchase satisfaction and repurchase. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, A.; Ishak, A.; Abdurrahman, A.; Astuti, B.; Marsasi, E. G.; Ridanasti, E.; Roostika, R.; Muhammad, S. COVID-19 Pandemic and Adaptive Shopping Patterns: An Insight from Indonesian Consumers. Global Business Review 2021, 0(0). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L.; Holmberg, U.; Post, A. Reorganising grocery shopping practices – the case of elderly consumers. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2022, 32(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H. Online grocery shopping before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analytical review. Telematics and Informatics 2022, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Nian Ci, T.; Kamarudin A, A.; Govindarajo, S. N.; Ting, C. L. (2023). Upsurge of Online Shopping in Malaysia during COVID-19 Pandemic. IntechOpen 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A.; Winkler, C.; Schmid, B.; Axhausen, K. In-store or online grocery shopping before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel Behaviour and Society 2023, 30, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaimo, L.S.; Fiore, M.; Galati, A. How the Covid-19 Pandemic Is Changing Online Food Shopping Human Behaviour in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolko Herceg, K. Utjecaj pandemije COVID-19 na online ponašanje potrošača u Hrvatskoj. CroDiM, 2021, 4(1), 131–140. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/254860.

- Diaz-Gutierrez, J. M.; Mohammadi-Mavi, H.; Ranjbari, A. COVID-19 Impacts on Online and In-Store Shopping Behaviors: Why they Happened and Whether they Will Last Post Pandemic. Transportation Research Record 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C. J.; Limongi, R.; De Sousa Júnior H., J.; Santos, S. W.; Raash, M.; Hoeckesfeld, L. Assessing the effects of COVID-19-related risk on online shopping behavior. Journal of Market Analytics 2023, 11, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.; Truong, D. M. How do customers change their purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, R. The Coronavirus Shopping Anxiety Scale: initial validation and development. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 2022, 31(4), 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Determinants of Consumers’ Online/Offline Shopping Behaviours during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, N.; Eschenbrenner, B.; Baier, D. Online shopping continuance after COVID-19: A comparison of Canada, Germany and the United States. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, A.; Caniato, F. Can Supply Chain Finance help mitigate the financial disruption brought by Covid-19? Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 2021, 27(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Das, R.; Kanti De, P. Impact of COVID-19 in food supply chain: Disruptions and recovery strategy, Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 2021, 2. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, S. and Seckin Aday, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Quality and Safety 2020, 4(4), 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwailem, A.A.; Salem, E.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; AlTameem, A.; AlKhathami, M.; Khan, M.B.; Hasanat, M.H.A. Impacts of COVID-19 on the Food Supply Chain: A Case Study on Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, E. J. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 2020, 68(2), 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Panchal, R.; Tiwari, M. Impact of COVID-19 on logistics systems and disruptions in food supply chain. International Journal of Production Research, 2020, 59(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, M. S. Food Supply Chain During Pandemic: Changes in Food Production, Food Loss and Waste. Journal of Environmental Impacts, 2021, 4(2), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ráthonyi, G.; Kósa, K.; Bács, Z.; Ráthonyi-Ódor, K.; Füzesi, I.; Lengyel, P.; Bácsné Bába, É. Changes in Workers’ Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Cinelli, G.; Bigioni, G.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Bianco, F.F.; Caparello, G.; Camodeca, V.; Carrano, E.; et al. Psychological Aspects and Eating Habits during COVID-19 Home Confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian Online Survey. Nutrients, 2020, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J. S.; Diaz, M.; Arnaboldi, M. Understanding panic buying during COVID-19: A text analytics approach. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Taha, V.; Pencarelli, T.; Škerháková, V.; Fedorko, R.; Košíková, M. The Use of Social Media and Its Impact on Shopping Behavior of Slovak and Italian Consumers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.; Sparke, K. Panic buying in times of coronavirus (COVID-19): Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand the stockpiling of nonperishable food in Germany. Appetite 2021, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.R., Blut, M., Xiao, S.H.; Grewal, D. Impulse buying: a meta-analytic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2019, 48, 384–404. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. An, N.; Gao, Z.; Kiprop, E.; Geng, X. Consumer food stockpiling behavior and willingness to pay for food reserves in COVID-19. Food Security, 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulos, K. D.; Lukas, M.; Wilson, O. S. J. Consumer Spending Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Assessment of Great Britain. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: implications for retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2020, 49(3), 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R. S.; Farrokhnia, A. R.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M.; Yannelis, C. How Does Household Spending Respond to an Epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies 2020, 10(4), 834–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, K.; Venkatesh, A.; Manivannan, R. S. A. Covid-19 is driving fear and greed in consumer behaviour and purchase pattern. South Asian Journal of Marketing 2021, 2(2), 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loske, D. The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: An empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, M.; Rizwan, S.; Ahmed, S.; Bin Khalid, H.; Naz, M. Discovering panic purchasing behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of underdeveloped countries. Cogent Business & Management, 2022, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Giroux, M.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, H.; Jang, S.; Kim, S. (S.); Park, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Lee, J. C.; Choi, Y. K. Nudging to reduce the perceived threat of coronavirus and stockpiling intention. Journal of Advertising 2020, 49(5), 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P. C.; Rifkin, S. L. I'll trade you diamonds for toilet paper: Consumer reacting, coping and adapting behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billore, S. and Anisimova, T. Panic buying research: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 45(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, M.; Neal, T. Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Econometrics 2021, 220(1), 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laato, S.; Najmul Islam, A. K. M.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadze, L.; Sraieb, M.M. Impact of Anti-Pandemic Policy Stringency on Firms’ Profitability during COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D.; Dennis, C. Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Business Research 2020, 116, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroux, M.; Park, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Choi, Y. K.; Lee, J. C.; Kim, S. (S.); Jang, S.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, H.; Kim, J. The Impact of Communication Information on the Perceived Threat of COVID-19 and Stockpiling Intention. Australasian Marketing Journal 2023, 31(1), 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L. A.; Hansen, T. E.; Johannesen, N.; Sheridan, A. Consumer responses to the Covid-19 crisis: evidence from bank account transaction data. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 2022, 124(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, M.; Shen, Y.; Ferasso, M; D’Adamo, I. Intensifying effects of COVID-19 on economic growth, logistics performance, environmental sustainability and quality management: evidence from Asian countries. Journal of Asia Business Studies 2022, 16(3), 448–471. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, M. C. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2020, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M.; Sousa, N.; Silva, R. COVID 19 and the Business Management Crisis: An Empirical Study in SMEs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L. A.; Hansen, T. E.; Johannesen, N.; Sheridan, A. Consumer Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Bank Account Transaction Data. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounie, D.; Camara, Y.; Galbraith, W. J. Consumers' Mobility, Expenditure and Online-Offline Substitution Response to COVID-19: Evidence from French Transaction Data. Economics Observatory 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oana, D. The Impact of the Current Crisis Generated by the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Behavior. Studies in Business and Economics 2020, 15(2), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanka, R.; Buff, C. COVID-19 Generation: A Conceptual Framework of the Consumer Behavioral Shifts to Be Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2020, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Crosta, A.; Ceccato, I.; Marchetti, D.; La Malva, P.; Maiella, R.; Cannito, L.; Cipi, M.; Mammarella, N.; Palumbo, R.; Verrocchio, C. M.; Palumbo, R.; Di Domenico, A. Psychological factors and consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayburn, W. S.; McGeorge, A.; Anderson, S.; Sierra, J. J. Crisis-induced behavior: From fear and frugality to the familiar. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 46(2), 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, C. D.; Kim, S. S.; Voyer, G. B.; Kim, C.; Sung, B.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, H.; Fastoso, F.; Choi, K. Y.; Yoon, S. The impact of COVID-19 on consumer evaluation of authentic advertising messages. Psychology and Marketing, 2021, 39(1), 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambefort, M. How the COVID-19 Pandemic is Challenging Consumption. Markets, Globalization & Development Review 2020, 5(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, X.; Zhao, T.; Ma, T. Conformity Consumer Behavior and External Threats: An Empirical Analysis in China During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SAGE Open 2021, 11(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. The Consumer in the Age of Coronavirus. Journal of Creating Value 2020, 6(1), 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chang, I. P. B.; Hristov, H.; Pravst, I.; Profeta, A.; Millard, J. Changes in Food Consumption During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Consumer Survey Data from the First Lockdown Period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-S.; Chen, J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Consumption Behavior: Based on the Perspective of Accounting Data of Chinese Food Enterprises and Economic Theory. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Paço, A.; Dinis, P. A. M.; Vidal, G. D.; Da Cunha, A. D.; de Vasconcelos, R. C.; Baumgartner, J. R.; Rampasso, I.; Anholon, R.; Doni, F.; Sonetti, G.; Azeiteiro, U.; Carvalho, S.; Rios, M. J. F. The influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable consumption: an international study. Environmental Sciences Europe 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlich, M. "COVID-19 Induced Changes in Consumer Behavior". Open Journal of Business and Management 2021, 9(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D.; Guidetti, M.; Capasso, M.; Cavazza, N. Finally, the chance to eat healthily: Longitudinal study about food consumption during and after the first COVID-1 lockdown in Italy. Food Quality and Preference 2022, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, J.; Skevas, T.; Segovia, M.S. Grocery Shopping Preferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attina, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; Esposito, E.; De Lorenzo, A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2020, 18(229). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimpo, M.; Akamatsu, R.; Kojima, Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food and drink consumption and related factors: A scoping review. Nutrition and Health 2022, 28(2), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Wilson, S. Consumption practices during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 46(2), 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callinan, S.; Mojica-Perez, Y.; Wright, C. J. C.; Livingston, M.; Kuntsche, S.; Laslett, M. A.; Room, R.; Kuntsche, E. Purchasing, consumption, demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with shifts in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug and Alcohol Review 2021, 40(2), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodkiewicz, J.; Talarowska, M.; Miniszewska, J.; Nawrocka, N.; Bilinski, P. Alcohol Consumption Reported during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Initial Stage. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, R.; Vaccaro, M. C. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases 2020, 30(9), 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sarkar, A.; Debroy, A. Impact of COVID-19 on changing consumer behaviour: Lessons from an emerging economy. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 2022, 46(3), 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresiene, D.; Keliuotyte-Staniuleniene, G.; Liao, Y.; Kanapickiene, R.; Pu, R.; Hu, S.; Yue, X.-G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer and Business Confidence Indicators. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2021, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M. C.; Rizou, M.; Aldawoud, S. M. T.; Rowan, J. N. Innovations and technology disruptions in the food sector within the COVID-19 pandemic and post-lockdown era. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 110, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, K.; Min, J.; White, B. Hope, fear, and consumer behavioral change amid COVID-19: Application of protection motivation theory. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2022, 46(2), 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, G. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis and Sustainable development. In Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis. State of the Art Surveys. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science 2005, 78, 953–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, G. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis and Sustainable Development. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science 2016, 233, 1235–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, R.V. Introduction to multiple attribute decision-making (madm) methods. Decision Making in the Manufacturing Environment, 2007, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenius, J.; Dyer, S. J.; Fishburn, C. P.; Steuer, E. R.; Zionts, S.; Deb, K. Multiple Criteria Decision Making, Multiattribute Utility Theory: Recent Accomplishments and What Lies Ahead. Management Science 2008, 54, 1339–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati, A.; Haghshenas, H.; Ghadirifaraz, B.; Laghaei, J.; Eftekhari, G. Applying AHP and Clustering Approaches for Public Transportation Decision Making: A Case Study of Isfahan City. Journal of Public Transportation 2016, 19, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Y. A Novel Distance Function of D Numbers and Its Application in Product Engineering. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2016, 47, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Pradhan, B.; Xu, C.; Bui, T. D. Spatial prediction of landslide hazard at the Yihuang area (China) using two-class kernel logistic regression, alternating decision tree and support vector machines. CATENA 2015, 133, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H.; Hashim, M.; Ahmad, B. B. Remote sensing and GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio, logistic regression, and fuzzy logic methods at the central Zab basin, Iran. Environmental Earth Sciences 2015, 73, 8647–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchini, K. E.; Emami, N. S.; Tahmasebipour, N.; Pourghasemi, R. H.; Naghibi, A. S.; Arami, A. S.; Pradhan, B. Assessment and comparison of combined bivariate and AHP models with logistic regression for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Chaharmahal-e-Bakhtiari Province. Iran Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2016, 9. [CrossRef]

- Prokos, H.; Baba, H.; Lóczy, D.; El Kharim, Y. Geomorphological hazards in a Mediterranean mountain environment–example of Tétouan, Morocco. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2016, 65, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzougagh, B.; Dridri, A.; Boudad, L.; Kodad, O.; Sdkaoui, D.; Bouikbane, H. Evaluation of natural hazard of Inaouene Watershed River in northeast of Morocco: Application of morphometric and geographic information system approaches. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies 2016, 19(1), 85–97. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342888363_Evaluation_of_natural_hazard_of_Inaouene_Watershed_River_in_Northeast_of_Morocco_Application_of_Morphometric_and_Geographic_Information_System_approaches.

- Siekelova, A.; Podhorska, I.; Imppola, J. J. Analytic hierarchy process in multiple-criteria decision-making: A model example. Proceedings of International Conference on Entrepreneurial Competencies in a Changing World 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J. J. Analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Studies in Systems, Decision and Control 2021, 336. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E. and Pereyra-Rojas, M. Practical Decision Making Using Super Decisions V3. Springer Briefs in Operations Research 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, B.; Özceylan, E. E.; Kabak, M.; Dikmen, A. U. Evaluation of criteria and COVID-19 patients for intensive care unit admission in the era of pandemic: A multi-criteria decision making approach. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjanto, S.; Setiyowati, S.; Vulandari, R. T.; Surakarta, S. N. Application of analytic hierarchy process and weighted product methods in determining the best employees. Indonesia Journal of Applied Statistics 2021, 4(2), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç, A.; Eren, T. Determination of KOSGEB Support Models for Small- and Medium-Scale Enterprises by Means of Data Envelopment Analysis and Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods. Processes 2019, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, C. B.; Okumuş, A.; Adıgüzel Mercangöz, B. An intelligent approach for analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on marketing mix elements (7Ps) of the on-demand grocery delivery service. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 2022, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Hasrini and Diningtyas Aulia Nurhadi. “Designing Marketing Strategy Based on Value from Clothing-producing Companies Using the AHP and Delphi methods.” Jurnal Teknik Industri. 2019, 20(2), 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Boroujerdi, S. S.; Husin, M. M.; Mansouri, H.; Alavi, A. Crafting a Successful Seller-Customer Relationship for Sports Product: AHP Fuzzy Approach. New Approaches in Exercise Physiology, 2020, 2(3), 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.-H.; Hsu, K.-Y.; Fu, H.-P.; Teng, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-J. Integrating FSE and AHP to Identify Valuable Customer Needs by Service Quality Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoera, I. C.; Olufayo, O. T.; Bulugbe, T. O. The Influence Of Retargeting And Affiliate Marketing On Youth Buying Behaviour Using The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). UNILAG Journal of Business 2022, 8(2). [Google Scholar]

- Produção, G.; Pessanha, L.; Morales, G. Consumer behavior in the disposal of Information Technology Equipment: characterization of the household flow. Gestão & Produção 2020, 27(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesic, I.; Pivac, T.; Lopatny, M. Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Tourist Destination Choice: A Case Study of Croatia. Conference: Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe 2021: ToSEE – Smart, Experience, Excellence & ToFEEL – Feelings, Excitement, Education, Leisure. 2021, 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. R.; Matsui, T.; Park, J. Y.; Okutani, T. Perceived Consumer Value of Omni-Channel Service Attributes in Japan and Korea. Engineering Economics 2019, 30(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catic, L.; Poturak, M. Influence of brand loyalty on consumer purchase behavior. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 2022, 11(8), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrayani, R. Identify Consumer Behavior in Choosing Delivery Services in Shopping in the Digital Era, Journal of Research in Business, Economics, and Education. 2021, 3(6), 198–203. Available online: https://e-journal.stie-kusumanegara.ac.id/index.php/jrbee/article/view/356.

- Jhaveri, A. C.; Nenavani, M. J. Evaluation of eTail Services Quality: AHP Approach. Vision 2020, 24(3), 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, J. Development of an AHP hierarchy for managing omnichannel capabilities: a design science research approach. Business Research 2020, 13, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Al Qassimi, N.; Abdelaziz Mahmoud, N.S.; Lee, S.Y. Analyzing the Housing Consumer Preferences via Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Behavioral Science 2022, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, A. and Dhurkari, R. Shopping Goods and Consumer Buying Behavior: An AHP Perspective. Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computers in Management and Business, 2018, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Pineda, Abraham, Jose Alejandro Cano, and Rodrigo Gómez-Montoya. 2021. Application of AHP for the Weighting of Sustainable Development Indicators at the Subnational Level. Economies 9. [CrossRef]

- Ristanović,V., Primorac,D. & Mikić,M.(2023).Application of Multi-Criteria Assessment in Banking Risk Management. International Review of Economics and Business 26(1), 97-117. [CrossRef]

- Ristanović, V.; Primorac, D.; Kozina, G. Operational risk management using multi-criteria assessment (AHP model). Tech. Gaz. 2021, 28, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. L. How to make a decision: The analytic decision process. European Journal of Operational Research, 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. L. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gutić, Dragutin and Šostar, Marko. Organizacija poduzeća. Univerzitet modernih znanosti CKM Mostar; Studio HS Internet. Osijek, Hrvatska, 2017.

| Sex | No |

| Male | 201 |

| Female | 358 |

| Age range | No |

| 18 to 25 | 134 |

| 26 to 35 | 117 |

| 36 to 45 | 173 |

| 46 to 55 | 79 |

| More than 56 | 56 |

| Occupation or Job status | No |

| Jobless | 148 |

| Gainfully employed | 411 |

| Relationship status | No |

| Not married | 241 |

| Married | 318 |

| Monthly earnings | No |

| Max 499 euro | 127 |

| 500 to 799 euro | 83 |

| 800 to 1099 euro | 153 |

| More than 1099 euro | 196 |

|

n |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

|

RI |

0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 1.11 | 1.25 | 1.35 | 1.40 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.51 | 1.48 | 1.56 | 1.57 |

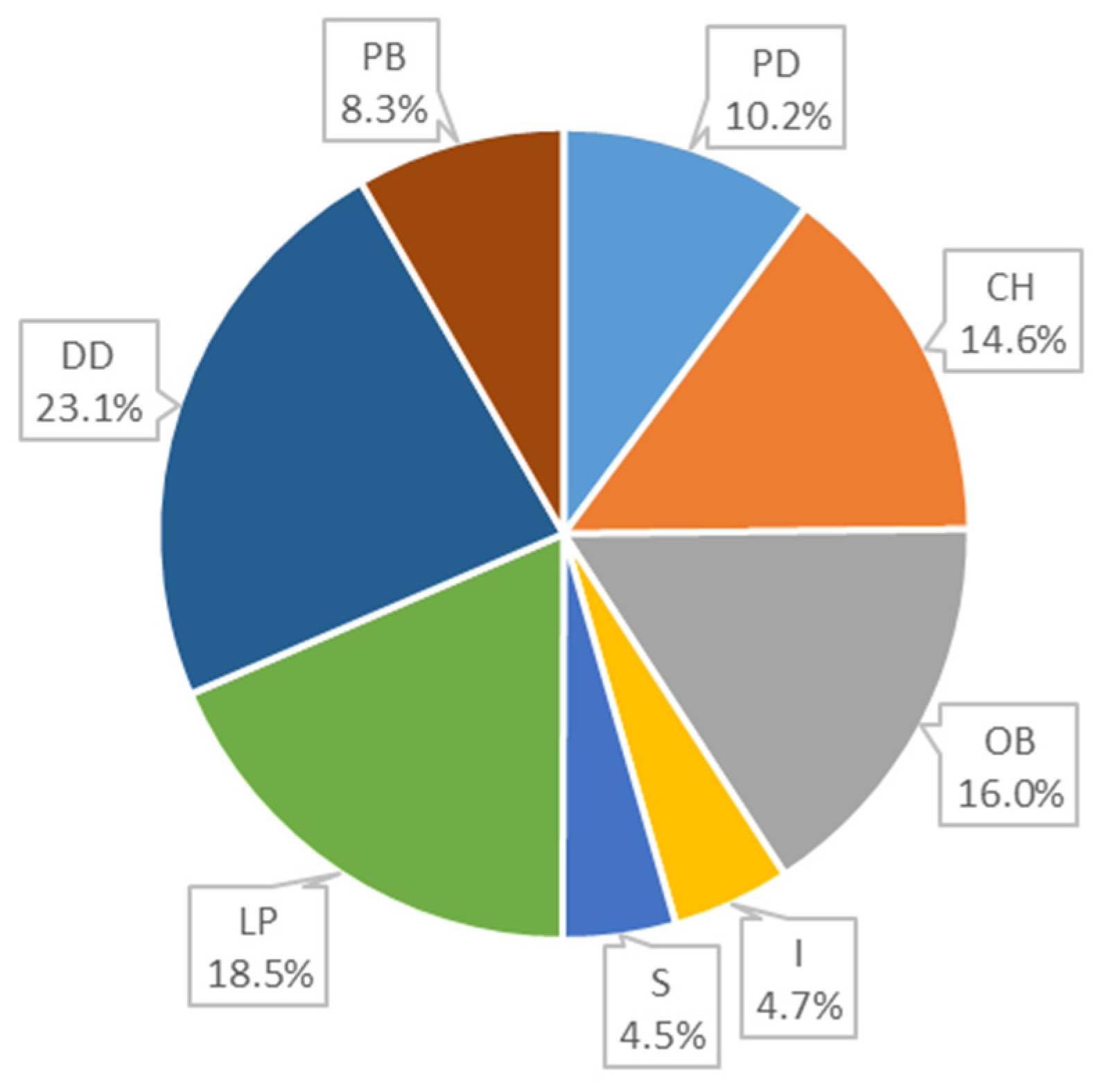

| Alterntives/ Criteria | PD | CH | OB | I | S | LP | DD | PB |

| PC | 0.387 | 0.269 | 0.237 | 0.248 | 0.177 | 0.168 | 0.264 | 0.275 |

| DC | 0.198 | 0.222 | 0.173 | 0.195 | 0.140 | 0.231 | 0.183 | 0.198 |

| SC | 0.140 | 0.128 | 0.138 | 0.137 | 0.264 | 0.117 | 0.139 | 0.140 |

| PS | 0.275 | 0.381 | 0.452 | 0.419 | 0.419 | 0.484 | 0.481 | 0.387 |

| MATRIX | ||||||||

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | |

| λmax | 4.12 | 4.22 | 4.12 | 4.22 | 4.14 | 4.12 | 4.22 | 4.12 |

| RI | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| CI | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| CR | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| PD | CH | OB | I | S | LP | DD | PB | Priorities | range | |

| PC | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 3 |

| DC | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 2 |

| SC | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 4 |

| PS | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 1 |

| Weight vector |

(0.10) | (0.15) | (0.16) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.19) | (0.23) | (0.08) | 1.00 | |

| rang | 5 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).