1. Introduction

The CAP 2023-2027 confirmed the European Partnership for Innovation in Agriculture (EIP AGRI) as the preferred instrument for accelerating innovation and knowledge sharing. This European initiative had a high degree of implementation in the 2014-2022 programming period, both at European and Italian level. In Italy, regional public institutions allocated more than 270 million euro to the implementation of 720 Operational Groups (OGs) projects, multi-actor partnerships that worked or are still working to identify and introduce innovative solutions to respond to farmers' problems.

The EIP AGRI bases its implementation on the so-called "interactive approach" [

1] which 20-year studies have shown to be the most effective way of introducing innovation [

2]. According to this approach, the interventions are carried out by a diverse group of actors (multi-actor approach), such as farmers, consultants, researchers, processing industries, and others directly involved in identifying, developing, and introducing specific innovative solutions [

3].

The literature on the interactive approach in the context of EIP AGRI is still limited, both at national and international level, being its implementation recent and, thus, scarce the availability of data on it. Hence, the Horizon 2020 projects that studied the interactive approach included in their investigations all multi-actor-related experiences, even those not necessarily linked with EIP AGRI [

4,

5]. The existing studies on the Italian OGs concentrate primarily on procedures, financial and governance aspects [

6,

7]. An analysis of farmers’ participation and the factors affecting their engagement and promoting interactive innovation processes was carried out in the Veneto region [

8], although the study is based on a single OG. Similarly,

Harrahill et al. [

9] studied the dynamics of farmers’ participation in an OG in Ireland, with a focus on how their knowledge shaped the operation of the OG and the bioeconomy activities within it.

Considering the relevance given to this approach by the EC and for the success of the EIP AGRI initiative, it seems useful to verify its implementation by the OGs. A first level of analysis should investigate how the main components of the approach have been implemented in the project activities, with particular attention to the interaction between partners (farmers, consultants, researchers, other actors included in the group), considered one of its most important elements [

10]. Another level of analysis refers to the process used by OGs to identify innovative solutions based on real farmers’ problems/opportunities. Furthermore, it is useful to understand the links between the distribution of roles and tasks within the partners and the identification of farmers' needs and innovative solutions. Finally, important indications on the application of the EIP AGRI approach could derive from the analysis of communication flows and tools.

The paper presents the main results of a research carried out in 2020-2022, which analysed the interactive approach as implemented by the EIP AGRI Italian OGs, with a specific focus on the abovementioned items. The main scope of this work is twofold, understanding how much effective the implementation of this approach has been for the national agricultural, food and forestry sectors and providing insights and suggestions to improve funding and implementation processes set up by the 2023 –2027 CAP that has confirmed and enhanced the European action on knowledge and innovation.

1.1. Theoretical background

In the context of the European agricultural policies, AKIS is described as “a system of innovation, with emphasis on the organisations involved, the links and interactions between them, the institutional infrastructure with its incentives and budget mechanisms”[

1]. The definition summarizes the results from research and/or development activities about the knowledge and innovation process of the recent decades and focuses on the need to connect science and practice in an effective way and to boost knowledge exchange and innovation for the benefit of farmers [

1,

11].

This setting is based on the “interactive approach” that is the acknowledgment of all actors’ contribution to the creation and sharing of knowledge and innovation. The involvement of the heterogeneity of AKIS actors [

12] also implies the enhancement of their effective abilities and skills in the implementation of the different activities connected to the knowledge and innovation process [

13]. Especially, it recognizes the importance of innovation resulting from both research and from practice; this coexistence is based on the enhancement of equal dignity in the innovation process [

14].

Sewell et al. [

15] consider as key issue of the interactive approach the focus on farmers and their real needs. This aspect, highlighted by many studies on innovation pathways, is often graphically synthesized by placing the farmers at the centre of the AKIS, as the most important node of an innovation cluster. This representation highlights the importance to deliver tailor-made solutions, aimed to solve concrete problems or seize opportunities to improve their existing farming activities, rather than focusing the process on innovation

per se. It is therefore clear that the word “interactive” does not only refer to possible relations among actors, but also and mainly to relations among objectives and knowledge, in an iterative process of co-construction.

Usually, these key elements are introduced in research or innovation projects that have the aim to improve the development or the sustainability of farms, sectors, areas, districts. They are named participatory or co-innovation projects and they are common in European policy interventions related to research (Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe), rural development and many other objectives. Ingram et al. [

16] underlined the risk of transforming this approach into a “rhetorical mainstreaming” rather than in a method to promote ideas, research results and innovations useful to solve the problems of farms and territories. The most important attentions regard the joint definition of problems/opportunities, the common construction of programs, the concerted testing of solutions [

17] and eventually redesign of activities. For a real participatory and co-innovation project it is necessary to have an adaptive cycle of plan-do-review [

18] between all project actors. Many authors emphasize the need for an iterative exchange among the actors, through repeated interaction in all phases of the innovation activities [

19,

20,

21].

Since the interactive/participatory approach is not simple to implement due to the different interests, points of view and roles of the actors involved, these projects need the presence of facilitation actions along the different stages of the project implementation [

22,

23], which can be promoted by the public funding institutions [

7]. This function is important in all project phases: during the needs analysis, when building the network, deciding upon objectives and solutions, when the first results are available and in case of changing in the structure and activities of the projects. It substantially regards all the innovation process management [

24]. The function of facilitation in co-innovation projects has been lately named brokerage or innovation support [

25] and it can be played by different actors with specific competencies and skills. Advisors are often recommended for innovation brokerage activities, given their important role in accompanying farmers during changes and business growth. Despite the importance of this function, there is still a lack of studies on how the role of advisors is managed within the OGs and their contribution to the innovation process.

Parzonko et al. [

26] [

24] analysed the role of the innovation broker in the formation of the EIP-AGRI OGs. They show that the main tasks of an innovation broker consist of supporting entities interested in cooperating to obtain funds for innovative activities; preparing project proposals and handling all documents related to the functioning of the OG; and identifying suitable actors to be included in the cooperation project.

Another key aspect is the dissemination of the results of the innovation/research projects towards a wider rural territory and any other farms interested. Indeed, in the partnerships of co-innovation projects a small number of actors is involved compared to the large number of potential users, and the aim of the rural development policies based on the interactive approach is the diffusion of innovative solutions. Therefore, to complement and make the projects results more effective in practice, additional advisory activities are needed targeting the outside. Co-innovation projects do not always foresee thorough advisory actions; thus, public institutions should envisage specific interventions. Viewed from this angle, the OGs could be themself the actors playing the brokering function towards farmers and other actors in the rural territories. An online survey submitted to Spanish EIP-AGRI OGs to investigate their characteristics and functions [

27] reveals that they perform three main functions: innovation process management, demand articulation, and institutional support and innovation brokering.

1.2. The context of the study

In the 2014-2022 programming period, EIP AGRI had good results in Italy, in terms of activated initiatives and financial resources allocated. All Italian regions, except for Valle d’Aosta, implemented, within their Rural Development Programs (RDP), the measures to support the creation of OGs. As of April 2023, 720 OGs have been funded accounting for 227-million-euro, an average of 32-million-euro per year. Considering the link with rural development priorities, 38% of the OGs address competitiveness and viability issues, 30% relate to supply chains and risk management, 17% to ecosystems protection, 14% to climate change, and 1% to social inclusion and local development.

The OGs’ partnerships involved more than 5.500 partners, 46% of which are farms and 22% research institutions. Only 8% are advisory bodies.

This intervention was carried out in a not very innovative agricultural and rural context, considering that in the 2018-2020 period, only 11% of Italian farmers introduced innovations in their farms (Census of Agriculture 2021) and there is an important innovation gap between the Northern (22%) and Southern regions and islands (6%). Thus, a more extensive support action from policy makers to address and improve both human resources and farm structures is more necessary than ever.

2. Materials and Methods

The research is structured into two main strands of investigation, as follows:

The interaction processes inside and outside the OGs, analysed via an online survey.

The effectiveness of the interactive approach, analysed by using in-depth case studies.

The online survey was carried out by sending a questionnaire to the partners of the OGs. The 517 respondents of 270 Italian OGs filled in the online questionnaire submitted in two rounds, by using the CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing) methodology, before and during the pandemic. This approach does not allow statistically representative sampling, but it guarantees a remarkable speed in the collection of information. The questionnaire includes 20 questions, 17 of which investigated on (i) the partners’ role in the OG; (ii) methods used to ensure internal and external communication; (iii) methods and tools to collect partners’ needs; (iv) the lessons deriving from the participation in the OG for the different actors; (v) the specific conditions experienced by the OG during the COVID pandemic. Many questions envisaged the use of a 5-point Likert scale for the answer. The questionnaire targeted all OGs active in Italy by the end of 2021, included those that had already closed their projects, and all partners. The answers from different partners of the same OGs could ensure a different point of view about the functioning of the OG as a partnership and the effectiveness of the project implemented.

The results of the online survey were first analysed using descriptive statistical methods to identify some focal issues, on which some insights were developed, namely: the effectiveness of the interactions, the degree of communicative openness, the management capacity, the impact on professional skills, and the effects of the pandemic.

The selection of case studies (the second analysis tool) was based on the following criteria:

geographical location: north, central, and south Italy

progress of the project (advanced or concluded)

number of partners (between 6 and 10 partners, considering the average of Italian OGs)

production sector

horizontal issues.

To carry out case studies [

28], semi-structured interviews were employed to collect information useful for analysing the following aspects of the OGs:

The inclusion. Analysis of the heterogeneity of participants and the consideration of different perspectives represented within the partnership; the presence of categories of partners consistent with the problems addressed by the project and the innovative solutions identified; the type of actions carried out.

The process. Understanding whether the project activities enabled to enhance the knowledge assets of all partners, to involve the whole partnership and how.

The impact. Analysis of the partners’ satisfaction; the effectiveness of the participatory processes and of the new skills/abilities that emerged; and the correspondence of the innovative solutions to the problems and opportunities identified in the planning phase.

The interviews allowed to describe all phases of the process (from the project design to the implementation of the planned actions), in terms of relationship among partners, and between them and all other external actors.

Overall, 10 case studies in 6 different regions were run and 64 actors were interviewed, including 20 researchers, 30 farmers, 4 advisors and 10 other actors (

Table 1).

The OGs covered by the case studies are briefly described below.

OG Beenomix 2.0 – Genomics and sustainability in Beekeeping.The project aims to improve the prospects of genetic selection and conservation in beekeeping, developing an open fertilization station prototype (ADA, Mating Area) and a diagnostic tool, based on SNP markers, for the racial recognition of Apis mellifera varieties and the development of a test for the SDL locus.

OG Biofertimat – Use of recycled matrices as fertilizers for organic fruit and vegetable crops. An approach to improve the local circular economy. The project aimed to identify the alternative organic matrices to mineral fertilization more suitable for organic farming deriving from agricultural by-products or agri-food waste.

OG Bovini – Integrated approach to reduce the consumption of antibiotics in milk production used to produce regional PDO cheeses. As stated in the title, the project aims to build a path to diminish the consumption of antibiotics in dairy cow farms to produce PDO cheeses in Emilia-Romagna, through the application of innovative tools for the quantification of the antibiotics and the evaluation of biosafety and well-being parameters.

OG Cheesmine – Experimental path of cheese maturing in the Dossena mines. The project aimed to define a production specification for bovine and goat cheeses to standardize the cheese-making processes, with microbiological and structural characteristics suitable for aging in mines.

OG Innobier – Basic business models for the production of beer from sustainable and innovative agriculture.The main objective was to build business models for the development of a South Tyrolean agricultural beer value chain, taking into consideration all stages of beer production, from both technical (e.g., choice of the most suitable cereal; malting process; etc.) and economic point of view (investments per farms’ type; profitability, marketing).

OG Irrigation Systems – Rationalization of irrigation systems for tree crops in response to climate change.The objective was to rationalize the irrigation systems for tree crops and introduce innovative techniques of air conditioning of the orchards.

OG I.T.A. 2.0 – Risk management 2.0: research, monitoring, processes, technologies and online communication, for the competitiveness of quality agriculture. The project aims to make the insurance chain more efficient by increasing the potential types of damages covered (natural disasters, plant diseases and price volatility of agricultural products), through the use of new methods of quantifying the damage and with the introduction of innovative financial instruments.

OG Rovitis 4.0 – Robotic management of the vineyard. The project aimed to develop two small-sized prototype robots used to manage the cultivation practices in the vineyard (defence, localized mechanical weeding and canopy management), implementing the dialogue activities between the robotic medium, sensors and the Decision Support System.

OG Salvarebioviter. – Recovery, protection and valorisation of the viticultural biodiversity of Emilia-Romagna. The project aims to counter the risk of loss of regional viticultural biodiversity, through the agronomic and oenological enhancement of varieties at risk of erosion as well as the genetic characterization and ampelographic of other varieties.

OG Small fruits Marche – Innovative solutions to extend the production and ripening calendar of strawberries and small fruits in the Marche region. The project aims to introduce a precision irrigation system for the management of water and nutritional supplies to reduce cultivation inputs and the risk of environmental contamination in cultivation of berries.

Table 2.

Operational Groups per sector and cross-cutting theme.

Table 2.

Operational Groups per sector and cross-cutting theme.

| OG |

Region |

Sector |

Cross-cutting theme |

| Beenomix 2.0 |

Lombardia |

Apiculture |

Biodiversity |

| Biofertimat |

Veneto |

Horticulture |

Bio-fertilization |

| Bovini |

Emilia Romagna |

Cattle |

Antibiotic resistance |

| Cheesmine |

Lombardia |

Cheese making |

Local development |

| Innobier |

Provincia Bolzano |

Beer |

Farm management |

| Irrigation systems |

Emilia Romagna |

Fruit |

Irrigation |

| ITA 2.0 |

Provincia Trento |

Multisector |

Risk management |

| Rovitis 4.0 |

Veneto |

Viticulture |

Precision farming |

| Salvarebioviter |

Emilia Romagna |

Viticulture |

Biodiversity |

| Small Fruits |

Marche |

Fruit |

Market |

Each case study was analysed considering some items deemed relevant for the implementation of the interactive approach, namely: the connection to and appropriate consideration of the users’ conditions and needs; the partnership characteristics with specific reference to competences and roles of single partners; the presence of innovation brokers and how they played their role in all project phases; the working dynamics existing among partners, with particular attention to the division of tasks and the quality/quantity of exchanges; the dissemination and advisory actions both for the approach used and tools chosen.

These criteria are summarised in

Table 3, which was used to provide a first synthetic opinion on the overall success of projects in relation to envisaged results and innovative effects.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Online Survey

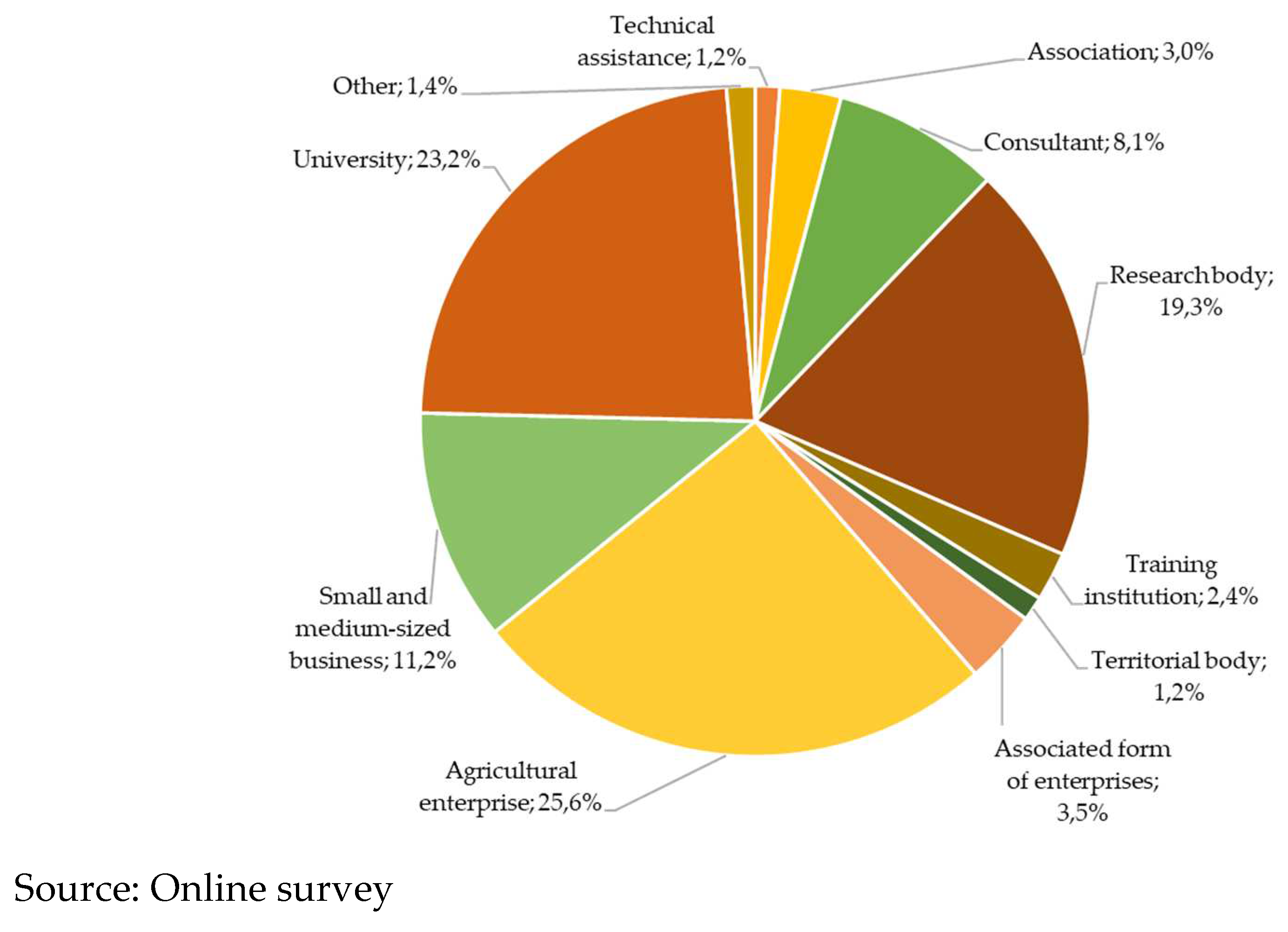

The breakdown of respondents by profile (

Figure 1) shows the relevant presence of universities and public research bodies (42.5%) followed by farmers and other small-medium entrepreneurs (36.8%). The share of consultants and technicians is modest (9.3%).

Regardless of the professional profile, each partner has a role in building and managing the OG. Almost half of the respondents are coordinators (45%) while 38% are targets of the innovation (

Table A1,

Appendix A). The main motivation to join the project (45% of the responses) is to find a solution to a problem that the innovation proposed by the OGs intends to solve. However, the need to share a common problem emerged too as a relevant motivation to be part of the group (30%).

The answers to the first three questions listed in

Table A2 (

Appendix A) provide some elements of evaluation on one of the key aspects of the EIP AGRI approach, that is, the interaction between actors. Relationships among partners are more intense between the leader and the innovators and gradually they fade away from the core of the group. This force of attraction exerted by coordinators was reduced by the pandemic and the consequent limitations to mobility and direct contacts. These limitations, however, facilitated the use of online communication tools and the growth of IT skills.

With reference to the communication aspects, the survey revealed that the information within the group circulates mainly in written form, followed by direct contacts between partners. External communications tools are more diversified and based on the use of the Internet (websites and social networks) (

Table A3,

Appendix A). The OGs envisage the provision of advice to partners especially through on-site meetings and visits for groups (66%) or individual contacts (52%). Advice to external actors, that is, not directly involved in the OG, was also provided through group meetings and visits (47%) but less individual contacts (21%) (

Table A4,

Appendix A).

The planning process that led to the identification of the OG’s activities for the adoption and diffusion of the innovation is usually linear, rarely with feedback interventions (

Table A5,

Appendix A). The innovation needs analysis was developed in the design phase, mainly through meetings with farmers (77%). Changes of the project planning are rare; 79% of respondents reported that no changes were needed. However, the analysis of the project calls in all Italian regions shows that relevant changes were not allowed by the regional funding bodies; this condition can explain the low level of adjustments during the implementation phase.

The participants were asked to evaluate the experience of cooperation within the OG (

Table A6,

Appendix A). The overall opinion is positive, not only for the results achieved in terms of innovative solutions (score 4), but also for the network of relationships and new skills acquired (scores 4.1 and 4). All the positive opinions about OGs have higher scores (>3) than the negative ones (<3).

To further assess whether these opinions are influenced by the organizational and relational methods adopted by the OGs, we crossed the Likert scores between questions to highlight possible existing correlations between the factors investigated, such as, for example, to evaluate if the satisfaction degree is related to the frequency of relationships between partners.

This analysis is performed by calculating the frequency distribution of the pairs of scores assigned by each participant. The resulting 5x5 contingency table is then aggregated excluding intermediate scores (3) to get four classes of score pairs

1. The following table 4 summarizes the percentages: high values indicate a direct relation between the evaluations, low values an opposite one. The presence of extreme values along the diagonals indicates a polarization of the answers, which confirms the reliability of the judgements. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient is also calculated

2 to assess the statistical significance of crossing answers.

The share of responses with high satisfaction and relational frequency (score >3) is equal to 39% of the total, against 6% of those who assign a low score (<3). The most satisfied are those who have more frequent contacts, but it should be noted that even a high relational frequency might be associated with negative judgments (20%); on the contrary, a low frequency of relationships is not linked to a fair level of satisfaction (2.5%).

Compared to the frequency of information circulated between partners, the incidence of the highest scores reaches 46% against 6% of those assigning a score lower than 3. Therefore, a greater intensity of information exchanges seems to be linked to greater satisfaction of OG members; this assessment is reinforced by the fact that a low percentage of respondents (3%) were satisfied in situations of poor circulation of information. However, it should be considered that 16% said they were satisfied even if the dissemination of information was modest.

Summarizing, a greater frequency of contacts and information exchanges between partners are the recurring characteristics of the OGs that have achieved the results deemed most satisfactory according to the survey participants. The correlation coefficients confirm the statistical significance of this link; the result appears to be more robust in relation to information exchange.

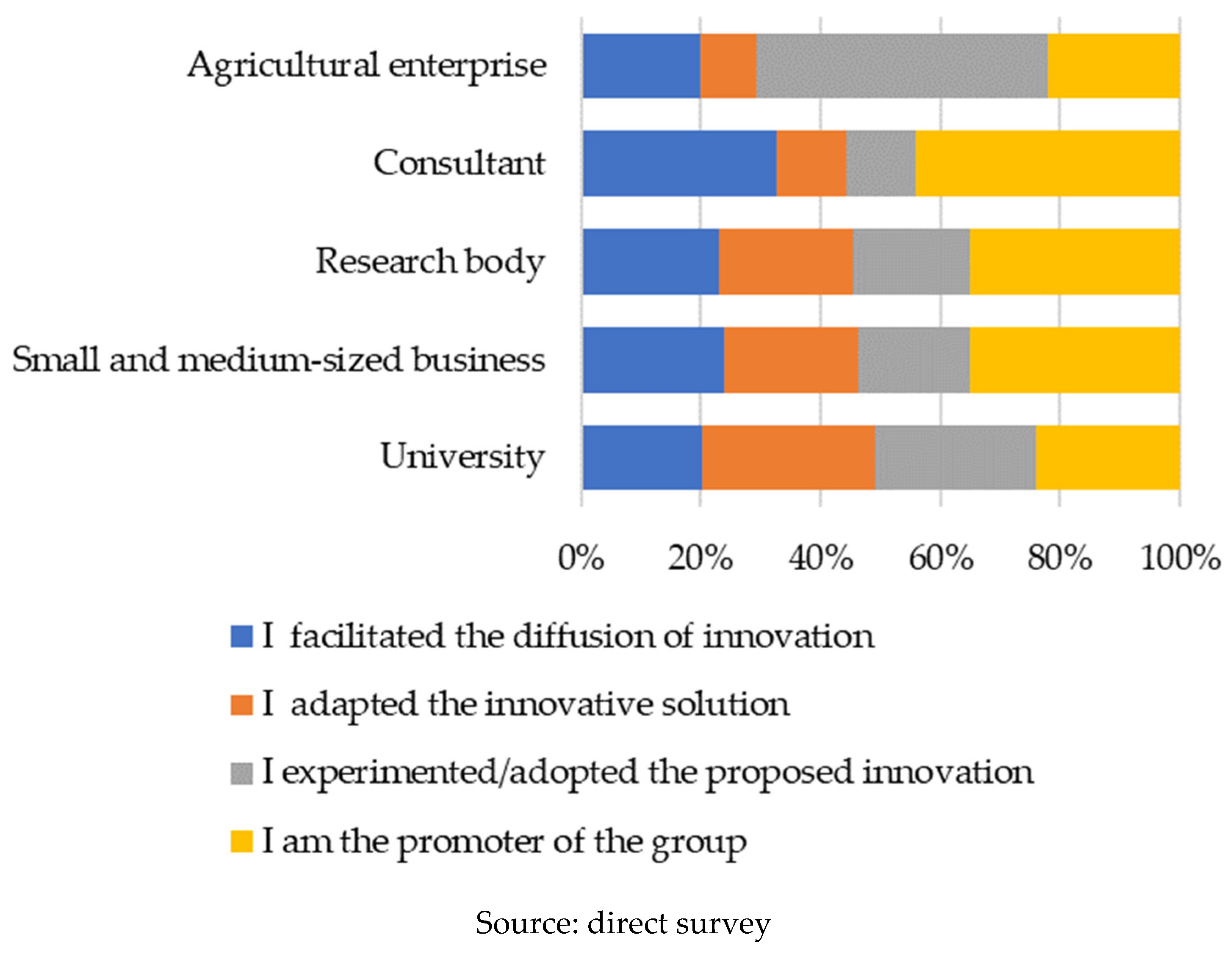

The key principles of the interactive approach are therefore effective in achieving the objectives of the Italian OGs. However, given the heterogeneity of the OGS’ partners, we consider relevant to understand the role individual partners played within the group. Crossing the answers to the question on the role within the OG (

Table A1) with the partner category we obtain the frequency distribution represented in

Figure 2.

Source: direct survey

We can outline how farmers play a predominantly “passive” role in implementing the innovation, while consultants, when involved in the OGs, are more committed in coordinating and organizing the group. The roles of the other categories of partners are more diversified with a slight prevalence of the organizational position for research institutions and SMEs, while universities have carried out the important task of experimenting and adapting innovation to the specific operational context.

3.2. Case studies

The compared analysis of the case studies shows a general adherence to the interactive approach in the Italian experience, although in some cases not all its elements were adequately considered by the OGs analysed (

Table 5).

Rating scale: absent (1), poor (2) medium (3) good (4) very good (5)

The qualitative analysis highlights how the problems and opportunities identified by the OGs’ projects cover the key issues and sectors for the region or area considered and the aspects more important for the farms or SMEs involved. In addition, the proposed innovations are generally considered useful to solve the problems identified or enhance the opportunities.

Building the OG partnership and setting up the project objectives

The pathways observed for the identification of problems and related solutions are various.

In some cases, the identification of the issues to be tackled starts from farmers, which might be single farmers or small groups of them (Rovitis; Cheesmine, Small Fruits), interested to implement specific innovations, or associated farmers (Biofertimat; ITA 2.0; Innobier). In the latter, farmers’ associations go from cooperatives to producers’ organisations to farmers’ organisations, but in all cases, it is the association, which collects the needs of farmers and from them leads the definition of the problem to be analysed within the OG.

A second pattern of problem identification and definition links to the existence of specific interests of a public institution or private structure (Bovini; Irrigation Systems); in contexts characterized by problems relevant for an entire industry (such as the use of antibiotics) or an entire territory (such as water management), technical partners led the process and organise meetings with farmers to better define the problem and identify possible solutions, which are then formalized in the project proposal.

In a third pattern the scientific partners lead the process of definition of the problem (Beenomix; Salvarebioviter), which derives, however, from the interaction with farmers and producers, originating from previous projects (Beenomix) or from traditional cooperation with farmers in a certain geographical area (Salvarebioviter).

A fourth pattern can be identified in relation to the process that the lead partner, regardless its nature, followed to define the project idea, process which appear to be based on a shared idea among potential members of the partnership and the defined by a process of interaction within them and with other actors, which might decide to join the group (ITA 2.0, Beenomix, Innobier).

Despite the consistency between problems/opportunities identified and innovations proposed, sometimes the solutions were not immediately usable in the farms, for multiple reasons highlighted as follows: i) need of further experimentations to introduce the innovation on the ground (Biofertimat); ii) inaccurate costs/benefits analysis related to the introduction of the proposed innovations, which required high initial investments not always affordable by farmers (Small fruits); iii) the adoption of the innovation was subordinated to conditions that were not yet present in the partners’ farms, such as farmers’ competences that needed to be reinforced, farms structure to be improved, or unsuitable soil conditions (Irrigation systems); iv) legal and security conditions were not yet available (Rovitis 4.0). Hence, the process of identification of problems and solutions often does not take into consideration the complexity of factors that could favour or hinder the adaptation and introduction of an innovation in a specific context, including viability, skills, culture and interest for new products or varieties.

Another issue to be highlighted is the research/experimental nature of some projects (Biofertimat, Salvarebioviter) that not always allow to reach all results and results ready for dissemination.

Partnerships’ integration: functioning, teamwork, and level of partners’ participation.

In most cases, the OGs’ partnerships were consistent with the problems to be addressed and the actions identified. This aspect was also influenced by the selection criteria envisaged in the calls for the financing of OGs’ projects.

Building partnership appropriate to the problem to be tackled and the innovations to be introduced is a needed condition but not necessarily sufficient to have a well-functioning partnership. The capacity to work in a team is a key condition, but it is well known that the teamwork is easy to understand and put down on paper in the planning phase but difficult to master in the implementation process.

The results of the case studies showed that the well-functioning partnerships were those with previous experience of projects based on a multi-actor approach (e.g., Salvarebioviter, Innobier). The presence of a partner playing an active mediating role is identified as an additional success factor in those partnerships considered as well-functioning by interviewees (Bovini, Innobier, Ita 2.0, Salvarebioviter), even in projects where potential competition between partners exists. The OG Bovini is an interesting example where the well-played role of the leader was key to promote the full engagement of potential competitors as partners, which agreed to share experimental results among them to improve the viability of the entire industry (producers of PDO cheese).

Two OGs experienced serious difficulties on these aspects: Rovitis 4.0 did not reach all expected results due to the controversies arose among partners and the difficulty to reach a compromise; the partners of Cheesime were not used to work as a team and to cooperate with others, and this caused arguments and disputes between partners, which were solved thank to the capacity of the leader to act in a balanced and coherent way and show the results of the innovation.

The small groups strategy, namely the creation of working groups based on the work to be done, was sometimes adopted to support the smooth functioning of the group and to reduce the distance between different partner typologies, such as farmers and scientists, and facilitate communication (e.g., Irrigation Systems, Ita 2.0). Limiting the involvement of the entire partnership proves how difficult it might be to promote the interaction, as envisaged in the EIP-AGRI approach. Furthermore, while this solution helps to reduce conflicts, it might as well decrease the full potential of the interactive approach, which lays on the interaction between partners and the possibility through it to co-create the solution.

Communication barriers between partners, which do not traditionally work together, such as farmers and researchers, are identified as the main obstacles to setting up good teamwork procedures. In some OGs these problems were prevented and/or solved by the presence of professionals with specific mediation capacities (Biofertimat, Bovini, Beenomix, Innobier), which were able to facilitate the dialogue between partners. They are often technicians of the farmers’ organisations, associations, cooperatives, producers’ organisations; on the one hand, they know farmers and their issues, on the other hand they are experts of the sector, they know production techniques and they can properly communicate with researchers, and at the same time to work as intermediaries between them and farmers. These experts are often advisors, and their presence in the OGs analysed is more common in those projects that have among the partners organisations representing associated farmers (e.g., producers’ organisations, consortia, farmers’ organisations, cooperatives). The low rate of advisors’ participation in the Italian OGs, linked to administrative issues experienced at the beginning of the programming period, deprived the EIP AGRI experience of a brokerage function, which could be essential to boost communication flows and contamination of languages.

Regarding the participation of farmers to the OGs project, it is important underline that often the non-recognition of their engagement, both in terms of time and economic compensation, due the eligibility of expenditure, reduced their interest in the OGs activities reflecting negatively on the project results.

Implementation of the project: definition of roles, distribution of tasks, and external factors.

Well-defined roles, and appropriate distribution of tasks among partners are, together with the above-mentioned teamwork, key elements of the interactive approach.

In the OGs analysed, the implementation of the projects was influenced, positively and/or negatively, by all elements mentioned above and especially by the clarity of tasks and roles. When partners, regardless of whether they were farmers (e.g., Biofertimat: Small fruits) or other core participants (e.g., Rovitis 4.0, Biofertimat), did not have a clear role and were not assigned well-defined tasks, the project management and the development of the results were not fluid and complete.

Another aspect that hinders the achievement of all results was the incomplete preliminary context analysis about the future application of the innovation (Innobier, Irrigation systems, Biofertimat, Small fruits), i.e., if farmers can introduce the proposed innovation given their competences and equipment available or if the chain is capable to support its introduction in the market.

Also, the presence of external factors can influence in a notable way planning and results of a project, such as climate change. By way of example, Beenomix 2.0, whose innovation consisted of sharing with beekeepers the importance of mating control for effective genetic improvement, was particularly influenced by adverse weather conditions; similarly, the success of Salvarebioviter, which aimed to grow ancient vines varieties, were undermined by not considered climate changes.

Implementation of the project: dissemination and role of advisors

The Italian OGs suffered the consequences of the COVID pandemic. The most negatively affected actions were the experimental tests and the dissemination/training. After a period of difficulties, the partnership reorganised the schedule and the modes of communication and continued their work.

The analysis of the case studies shows that planning, management and implementation of dissemination and the role of advisory are the most important weaknesses. Dissemination actions were usually set up in a traditional manner; often a detailed plan was prepared only at the end of the activities and using generics tools more suitable for a wide audience than specific users (newsletter, brochure, generic dissemination articles) or more adequate for scientific users (conference, seminar).

Most OGs examined did not apply the real interactive approach because the phase of dissemination and diffusion was managed outside the iterative process among partners. This situation had two consequences: the dialogue with the farmers inside the projects was very low and often there was not dissemination outside the project among the other farms potentially interested in the innovations. The already mentioned lack of advisors’ participation was the main reason for the difficulty to confront with farmers and their workers; however, this issue also reflects a cultural gap.

Differently, in some OGs (Bovini, Innobier, Salvarebioviter, Beenomix) the actions to involve farmers, within and outside the partnership, were implemented during the entire project process and improved the effectiveness of results. In at least one case (Innobier), the role of advisors was relevant not only to involve farmers but to solve problems arose during the implementation of the project.

The indicator of effectiveness and efficiency scores between 3 and 4.5; only in one case its value is 2.5 (Rovitis 4.0), linked to the conflicts between partners already mentioned (Table n. 5).

The overall evaluation of the OGs’ analysed retes from medium to good.

The reasons for the less brilliant performances lay on the following factors: i) the innovative solutions do not always fully respond to the needs of users and/or their uptake entails high costs; ii) the relations inside the partnership were not properly managed, especially those involving the users of the innovations; iii) dissemination was based on generic plans and tools, while targeting actions were usually dedicated to scientific users.

In these conditions, projects were positively concluded, but not all results were achieved and, more important, the innovative solutions did not have the diffusion desired (Biofertimat, Irrigation systems, Small fruits, Cheesmine).

In other cases, the results reached the envisaged users and more large number of users; so, the partnership of the projects became an investment for future experiences (Beenomix, Bovini, Innobier, Ita 2.0, Salvarebioviter).

4. Conclusions and recommendations

The two strands of investigation chosen by the study enable to draw some conclusions, even coincident.

Most OGs’ partners involved in the study considered problems, opportunities and related innovative solutions covered by the projects relevant to their work. Hence, we can state that in Italy the EIP AGRI was able to capture the real issues of farmers and other actors of rural territories. Given the novelty of EIP AGRI intervention, this outcome was not obvious, and it can be considered the result of a set of factors: a thorough information activity from public institutions and farmer’s associations, the good setting of calls for funding, the knowledge of economic, social and environmental context showed by the projects’ promoters, and the good level of dialogue among the components of partnerships, prior and during the project implementation.

A first positive effect of the OGs’ participation for the different actors was the possibility to build new relationships or improved the existing ones; that will be an important resource for the future AKIS activities in the different rural territories.

Another element emerging from the study regards the weight of researchers and farmers, or their representatives, within the partnerships. Both categories are always included in the partnerships; however, researchers had often a more active and determinant role, while farmers were usually passive during the implementation of the project, sometimes involved just to test some results.

Advisors, as already mentioned, participated as partners in few projects; when present, communication and information flows were more intensive and effective.

A common difficulty of OGs was the implementation of the interactive approach along all project phases. A continuous process of exchanges among partners, to understand if the implementation was on track or if adjustments were needed, was rarely found. In this respect, the process of dissemination of innovations can be considered the most critical; the actions to spread the innovation were usually plan at the end of the project and realized with traditional tools. This situation influenced, sometimes negatively, the full adoption of technologies, new organisation models and rationalised processes by the envisaged users.

This approach towards dissemination also influenced the diffusion of the OGs results outside the partnership, for which no specific actions were envisaged in most projects. However, they are published in the project websites, in the regional databases, when present, and in the national database (

www.innovarurale.it), thus available to be consulted by those interested to know more about them.

In Italy, therefore, the interactive approach that is the core of EIP AGRI was only partially implemented and there are ample spaces of improvement for Italian future OGs.

The study highlighted how hard is to measure and fully understand the process triggered by the interactive approach. Being this process influences by the specific context where the project is implemented and by the relationships existing between partners, it does not always assume the same shape, with similar characteristics. As mentioned in the first paragraphs, this approach has been studied for many years and it was evident how some of its key elements can favour or hinder the adoption of innovations. However, it cannot be considered as a predictive model, due to the complexity of fully defining the role of each component and its weight on the process. For example, the results of previous and present studies show that, when the actors work together, the innovation process is more effective; however, the intensity, modality and direction of this relation can be different according to the situation, thus, the effects can change. It follows that the experience studied in specific contexts can give essential insights about the interactive model, but they do not allow to define precise roles and criteria.

Instead, a result that this study cannot provide is the impact of the EIP AGRI on the agrifood system at local and/or national level, since the conclusion of the OGs’ projects is recent, and many are still working. The in-depth analysis of the effects the EIP AGRI in the long term might be the focus of a future study.

The analysis carried out in the present study allowed to formulate some recommendations for the future implementation of OGs, considering that they have been confirmed in the 2023-27 CAP programming period as privileged tool to boost innovation diffusion.

The analysis of the case studies highlighted that internal communication problems, directly related with low levels of interactions, can jeopardise the results of the projects. These difficulties were often solved or, at least, improved by the presence of an “intermediary”, that is, a member of the group who played the role traditionally described as the innovation broker. In few cases this role had been envisaged since the beginning of the project, and in those cases where an intermediary was not foreseen and found within the group, the project did not deploy its full potential. Thus, OGs should be encouraged to include such a role within their partnership since the beginning of the project. Within the Italian experience, the role of the innovation broker might be played by different types of actors, in most cases private but they might also come from public bodies. This variety depends on the different arrangements that exist at regional level in terms of organisation and management of the interventions promoting innovation. Whatever is the legal nature of the intermediary, however, this proved to be relevant to the success of the project. Whether a public or private actor might ensure more efficiency as innovation broker in the Italian context, or in another context characterised by such a variety of arrangements, might be an issue to be further studied.

The effectiveness of the interactions between actors appears to be positively affected by the presence of partners with previous work experience in interactive projects. Additionally, partnerships composed by partners which had already worked together in previous projects tend to encounter less communication problems and be more successful. Of course, the composition of the partnership depends on the objectives of the project; however, building a partnership around few actors who already worked together and integrating it with new members able to bring new ideas and perspectives might increase the potential success of projects. The promotion of other collaborative projects between the various AKIS actors could guarantee a greater ability to interact effectively also in the next GOs.

Regional administrations should make an additional effort to reduce administrative requirements and bureaucracy in relation to innovation projects, even by allowing OGs to modify the projects during the implementation phase. It can be argued that allowing important modifications increases uncertainty of results for the funding bodies; however, this risk should be adequately taken into consideration being uncertainty a built-in element of innovative projects.

Particular attention should be paid to the link of projects’ results with intellectual property rights. The possibility to patent the result of the project might create tensions within the partnership. Original results should be a legitimate aspiration of OGs partnership; nonetheless, their use might become difficult, and this might reduce the scope of the project itself. It might be wiser to focus on effective introduction of innovation and less on original results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Vagnozzi A. and Giarè F.; methodology Arzeni A. Giarè F. and Vagnozzi A.; data collection, Arzeni A., Giarè F., Lai M., Lasorella M.V., Ugati R., Vagnozzi A..; data curation, Arzeni A. and Lai M.; writing, Arzeni A., Giarè F., Lai M., Lasorella M.V., Ugati R., Vagnozzi A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian National Rural Network.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the interviewees for their availability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Online survey: questions and answers related to the involvement in the OG.

Table A1.

Online survey: questions and answers related to the involvement in the OG.

| Questions |

Responses |

% share on total |

| 1 - How would you define your role within the OG (individually or through the company/organisation you represent)? |

multiple choice |

| I am the promoter of the group |

234 |

45% |

| I adapted the innovative solution |

148 |

29% |

| I adopted the proposed innovation |

196 |

38% |

| I facilitated the diffusion of innovation |

183 |

35% |

| 2 - How did you get involved in the GO? |

single choice |

| I am among the promoters of the project |

246 |

48% |

| I was contacted by the OG leader |

144 |

28% |

| I was contacted by another OG partner |

50 |

10% |

| I knew about it through the technical assistance services |

7 |

1% |

| I was already linked with the OG subjects |

55 |

11% |

| By chance, I inquired and expressed my interest to participate |

5 |

1% |

| I attended a meeting about the OG topic and contact them |

9 |

2% |

| 3 - What is the main reason for your participation in the OG? |

single choice |

| I am interested in finding a solution to a problem |

232 |

45% |

| I found a solution and I want to spread it |

34 |

7% |

| The solution might more easily emerge from the interaction with others |

156 |

30% |

| I have the opportunity to complete a previous experience on the same topic |

63 |

12% |

| Other |

32 |

6% |

Table A2.

Online survey: questions and answers related to the relationships existing within the OG.

Table A2.

Online survey: questions and answers related to the relationships existing within the OG.

| Questions |

Pre-pandemic |

Post-pandemic |

Shift |

| 4 - How often did you interact with the other participants? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| With the leader |

4,3 |

4,1 |

-0,2 |

| With the innovation promoters |

4,1 |

4,0 |

-0,1 |

| With partners providing the technical-informative support |

3,8 |

3,6 |

-0,2 |

| With partners who have experimented/adopted the proposed innovation |

3,7 |

3,5 |

-0,2 |

| With partners who facilitated/disseminated the diffusion of innovation |

3,6 |

3,4 |

-0,2 |

| With companies receiving innovation |

3,5 |

3,2 |

-0,3 |

| With other participants of the OG |

3,7 |

3,5 |

-0,2 |

| With companies external to the OG interested in adopting/testing innovation |

2,5 |

2,2 |

-0,3 |

| With other agricultural consultants interested in the innovation |

2,5 |

2,1 |

-0,4 |

| With other OGs having similar problems/needs |

2,0 |

1,9 |

-0,1 |

| 5 - How often did you participate in the OG activities? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| Plenary meetings |

4,1 |

3,5 |

-0,6 |

| Subgroup meetings |

3,8 |

3,3 |

-0,5 |

| On-line contacts (email, whatsApp, social networks) |

4,2 |

4,2 |

0,0 |

| On-line activities by cooperative tools (e.g. online platforms, shared folders or documents, etc.) |

3,6 |

3,7 |

0,1 |

| Filed visits (farms, laboratories, etc.) |

3,5 |

2,9 |

-0,6 |

| Other interaction methods (specify) |

2,4 |

2,1 |

-0,3 |

| Scores: 1=very low frequency 5=very high frequency |

|

|

|

Table A3.

Online survey: questions and answers related communication within the OG.

Table A3.

Online survey: questions and answers related communication within the OG.

| Questions |

Multiple choices |

| 6 - How did you receive information on the OG's activities? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| Through documents dedicated to OG members |

4,0 |

| Through direct contacts with other OG members |

4,2 |

| Through documents also disseminated outside the OG |

2,8 |

| Participating in public events (e.g., seminars, media interviews) |

3,1 |

| Consulting information disseminated online (e.g., website, blog, social network) |

3,1 |

| Through ad hoc tools created for communication between OG partners |

3,4 |

| 7 - The OG spread public information about the project mainly through |

responses |

% share on total |

| Dedicated website |

284 |

55% |

| Generalist social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, etc.) |

183 |

35% |

| Scientific or professional social networks (ResearchGate, Linkedin, etc.) |

13 |

3% |

| Dissemination articles |

168 |

32% |

| Scientific articles |

57 |

11% |

| Seminars and workshops |

222 |

43% |

| Scientific conferences |

55 |

11% |

| Meetings and fields visits |

201 |

39% |

| Videos |

47 |

9% |

| Demo fields |

81 |

16% |

| Scores: 1=very low frequency 5=very high frequency |

|

|

Table A4.

Online survey: questions and answers about advisors.

Table A4.

Online survey: questions and answers about advisors.

| Questions |

Multiple choices |

| 8 - The OG advised entrepreneurial partners about innovation mainly through |

responses |

% share on total |

| Colective meetings and field visits |

342 |

66% |

| Video tutorials |

33 |

6% |

| Demo fields |

173 |

33% |

| On-site individual advice |

268 |

52% |

| Off-site individual advice |

37 |

7% |

| Remote individual advice (telephone, e-mail, chat, etc.) |

187 |

36% |

| On-site advice for small groups |

85 |

16% |

| Off-site advice for small groups |

46 |

9% |

| 9 - The OG advised external entrepreneurs about innovation mainly through |

responses |

% share on total |

| Colective meetings and field visits |

244 |

47% |

| Video tutorials |

75 |

15% |

| Demo fields |

162 |

31% |

| On-site individual advice |

108 |

21% |

| Off-site individual advice |

47 |

9% |

| Remote individual advice (telephone, e-mail, chat, etc.) |

132 |

26% |

| On-site advice for small groups |

64 |

12% |

| Off-site advice for small groups |

48 |

9% |

Table A5.

Online survey: questions and answers about the OG management.

Table A5.

Online survey: questions and answers about the OG management.

| Questions |

Multiple choices |

| 10 - In which phases of the project were the problems/needs of the farmers identified? |

responses |

% share on total |

| Collection of issues/needs during the design phase |

308 |

60% |

| Feedback check after some phases of the project |

98 |

19% |

| Feedback check after all phases of the project |

91 |

18% |

| Check after the last phase with partners and/or farmers |

20 |

4% |

| 11 - What tools were mainly used to identify the problems/needs of farmers? |

responses |

% share on total |

| Questionnaire to farmers partners for analysing issues/needs |

83 |

16% |

| Questionnaire to other farmers for analysing issues/needs |

46 |

9% |

| Meetings to assess the real needs of farmers |

398 |

77% |

| Informal gatherings during the activities |

263 |

51% |

| Interviews of farmers |

165 |

32% |

| Analysis of available statistical data |

130 |

25% |

| Applications (apps, social networks, etc.) for information gathering |

19 |

4% |

| 12 - Were changes introduced compared to the project presented? |

responses |

% share on total |

| No, there were no significant changes |

407 |

79% |

| Yes, the partnership changed |

42 |

8% |

| Yes, the objectives changed |

16 |

3% |

| Yes, the organisation of the activities changed |

62 |

12% |

| 14 - What issues were encountered during the project implementation? |

responses |

% share on total |

| Non-participation of all partners in the activities |

150 |

29% |

| Lack of funds dedicated to the exchanges/meetings between partners |

73 |

14% |

| Lack of actions for exchanges/meetings between partners |

37 |

7% |

| Understanding the needs of the different actors involved was difficult |

122 |

24% |

| Lack of a facilitator within the group |

37 |

7% |

| Lack of a business support consultant |

53 |

10% |

| Other |

59 |

11% |

Table A6.

Online survey: questions and answers about the results of the OG.

Table A6.

Online survey: questions and answers about the results of the OG.

| Questions |

Multiple choices |

| 13 - What changes has the OG produced in your professional environment? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| I have expanded my network of relationships |

4,1 |

| I introduced new organisational methods |

3,2 |

| I adopted a new tool/device |

2,9 |

| I acquired new skills |

4,0 |

| Other changes |

2,1 |

| 15 - Considering your OG's experience, how much do you agree with these statements? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| I investigated the problem to be addressed |

4,2 |

| Participation required too much time for me |

2,3 |

| The group of participants was too large |

1,7 |

| I understood the points of view of the other participants |

3,7 |

| The solution identified has been scarcely applicable or unsuitable |

1,7 |

| Timing to implement the project activities was too limited |

2,6 |

| With the project I learnt how to solve the problem |

3,3 |

| I was marginally involved in the decision-making process |

1,7 |

| I had the opportunity to develop new ideas |

3,8 |

| I enriched my initial knowledge (before the OG) |

4,0 |

| The OG's objectives should be limited (e.g. at territory or sector scale) |

2,4 |

| 16 - In a nutshell, how satisfied are you with the following aspects? |

weighted average score (1-5) |

| Results achieved by the OG |

4,0 |

| Involvement in activities |

4,2 |

| Relations with other participants |

4,1 |

| Organisation of the OG (e.g. methods of communication, frequency of meetings) |

4,0 |

| Other aspects |

2,6 |

| Scores: 1=strongly disagree; 5=completely agree |

|

References

- EU SCAR. Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems in Transition – A Reflection Paper. Brussels: European Commission, 2012.

- Maziliauskas, A.; Baranauskienė, J.; Pakeltienė, R. Factor of effectiveness of European Innovation partnership in agriculture. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 2018, 40, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, E.; Fosselle, S.; Rogge, E.; Home, R. An Analytical Framework to Study Multi-Actor Partnerships Engaged in Interactive Innovation Processes in the Agriculture, Forestry, and Rural Development Sector. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldsend, A. F.; Cronin, E.; Varga, E.; Biró, S.; Rogge, E. ‘Sharing the space’ in the agricultural knowledge and innovation system: multi-actor innovation partnerships with farmers and foresters in Europe. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 2021, 27, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldsend, A.F.; Varga, E.; Biró, S.; Von Münchhausen, S.; Häring, A.M. Multi-actor co-innovation partnerships in agriculture, forestry and related sectors in Europe: Contrasting approaches to implementation. Agricultural Systems. 2022, 202, 103472, ISSN 0308-521X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, E.; Ugati, R. I Gruppi Operativi e I progetti pilota di cooperazione. Una prima valutazione. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics 2018, 73, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarè, F.; Vagnozzi, A. Governance’s effects on innovation processes: the experience of EIP AGRI’s Operational Groups (OGs) in Italy. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics. 2022, 76, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, N.; Brunori, G.; Favilli, E.; Grando, S.; Proietti, P. Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrahill, K.; Macken-Walsh, Á.; O’Neill, E.; Lennon, M. , An Analysis of Irish Dairy Farmers’ Participation in the Bioeconomy: Exploring Power and Knowledge Dynamics in a Multi-actor EIP-AGRI Operational Group. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachoud, C.; Labeyrie, V.; Polge, E. , Collective action in Localized Agrifood Systems: An analysis by the social networks and the proximities. Study of a Serrano cheese producer’ association in the Campos de Cima da Serra/Brazil. Journal of Rural Studies, 2019, 72, 58–74, ISSN 0743-0167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU SCAR. Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems Towards the Future – a Foresight Paper, Brussels, 2015.

- Van Oost, I.; Vagnozzi, A. Knowledge and innovation, privileged tools of the agro-food system transition towards full sustainability. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics 2020, 75, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Geerling-Eiff, F.; Potters, J.; Klerkx, L. , Public-private partnerships as systemic agricultural innovation policy instruments – Assessing their contribution to innovation system function dynamics. NJAS–- Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences. 2019, 88, 76–95, ISSN 1573-5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, E.T.; Barnaud, C.; Girard, N.; Labatut, J.; Martin, G. How to foster agroecological innovations? A comparison of participatory design methods, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2016, 59, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Dwyer, J.; Gaskell, P.; Mills, J. Reconceptualising translation in agricultural innovation: A co-translation approach to bring research knowledge and practice closer together. Land Use Policy. 2018, 70, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, A.M.; Hartnett, M.K.; Gray, D.I.; Blair, H.T.; Kemp, P.D.; Kenyon, P.R.; Morris, S.T.; Wood, B.A. Using educational theory and research to refine agricultural extension: Affordances and barriers for farmers’ learning and practice change. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 2017, 23, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Gaskell, P.; Mills, J.; Dwyer, J. How do we enact co-innovation with stakeholders in agricultural research projects? Managing the complex interplay between contextual and facilitation processes. Journal of Rural Studies. 2020, 78, 65–77, ISSN 0743-0167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Kröger, M. Joint problem framing in sustainable land use research: Experience with Constellation Analysis as a method for inter- and transdisciplinary knowledge integration. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 526–539, ISSN 0264-8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, S.; García, M.C.; Peluffo, S.; Dieste, J.P.; Pedemonte, A.J.; Bacigalupe, G.F.; Scarlato, M.; Alliaume, F.; Alvarez, J.; Chiappe, M.; Rossing, W.A.H. Co-innovation of family farm systems: A systems approach to sustainable agriculture. Agricultural Systems, 2014, 126, 76–86, ISSN 0308-521X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M. C.; Morehouse, B. J. The co-production of science and policy in integrated climate assessments. Global Environmental Change, 2005, 15 57-68, ISSN 0959-3780. [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.R.; Chapman, D.F.; Paine, M.S. Networks of practice for co-construction of agricultural decision support systems: Case studies of precision dairy farms in Australia. Agricultural Systems, 2012, 108, 10–18, ISSN 0308-521X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L. J. Public Participation Methods: A Framework for Evaluation. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C.; Pyburn, R.; Röling, N.G. Wheelbarrows full of OGs: social learning in rural resource management: international research and reflections, Koninklijke Van Gorcum, 2002, 479, ISBN (Print)9789023238508, 2002.

- Ernst, A. Review of factors influencing social learning within participatory environmental governance. Ecology and Society, 2019, 24. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26796921.

- Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. ; Matching demand and supply in the agricultural knowledge infrastructure: Experiences with innovation intermediaries. Food Policy, 2008, 33, 260–276, ISSN 0306-9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybaert, C.; Debruyne, L.; Kyndt, E.; Marchand, F. Competencies for Agricultural Advisors in Innovation Support. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzonko, A. J. , Wawrzyniak, S., Krzyżanowska K.; The role of the innovation broker in the formation of EIP-AGRI Operational Groups. Annals of the Polish Association of Agricultural and Agribusiness Economists. XXIV. 194-208. [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Nieto-Alemán, P.; Marín-Corbí, J.; Garcia-Alvarez-coque, J.M. Collaboration through EIP-AGRI Operational Groupsand Their Role as Innovation Intermediaries’. New Medit 2021, 20, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. , Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, 2018, CA: Sage.

Notes

| 1 |

The four classes count the relative frequency of the score pairs: s1>3 and s2>3 (high-high); s1<3 and s2<3 (low-low); s1> 3 and s2<3 (high-low); s1< 3 and s2>3 (low-high).. |

| 2 |

The correlation is calculated by associating the average scores expressed by each participant for each answer option, in this way the integers values of the Likert scale are converted into continuous values. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).