Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Coaxial Nanowires

2.2. Sample Preparation for the Magnetic Impedance Measurement

2.3. Remaining Experimental Details

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure of the Samples

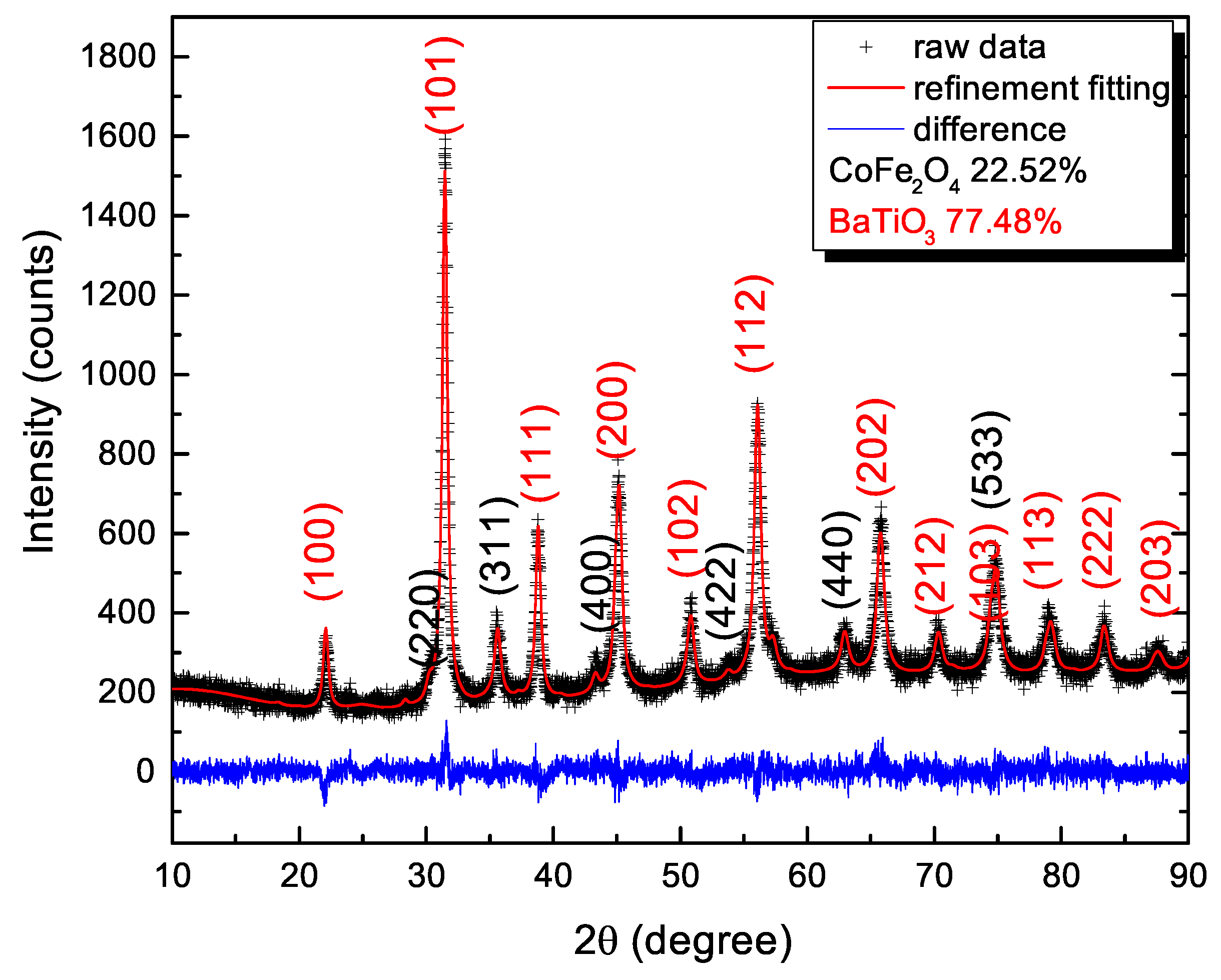

3.2. Phase Analysis of the Coaxial Nanowires

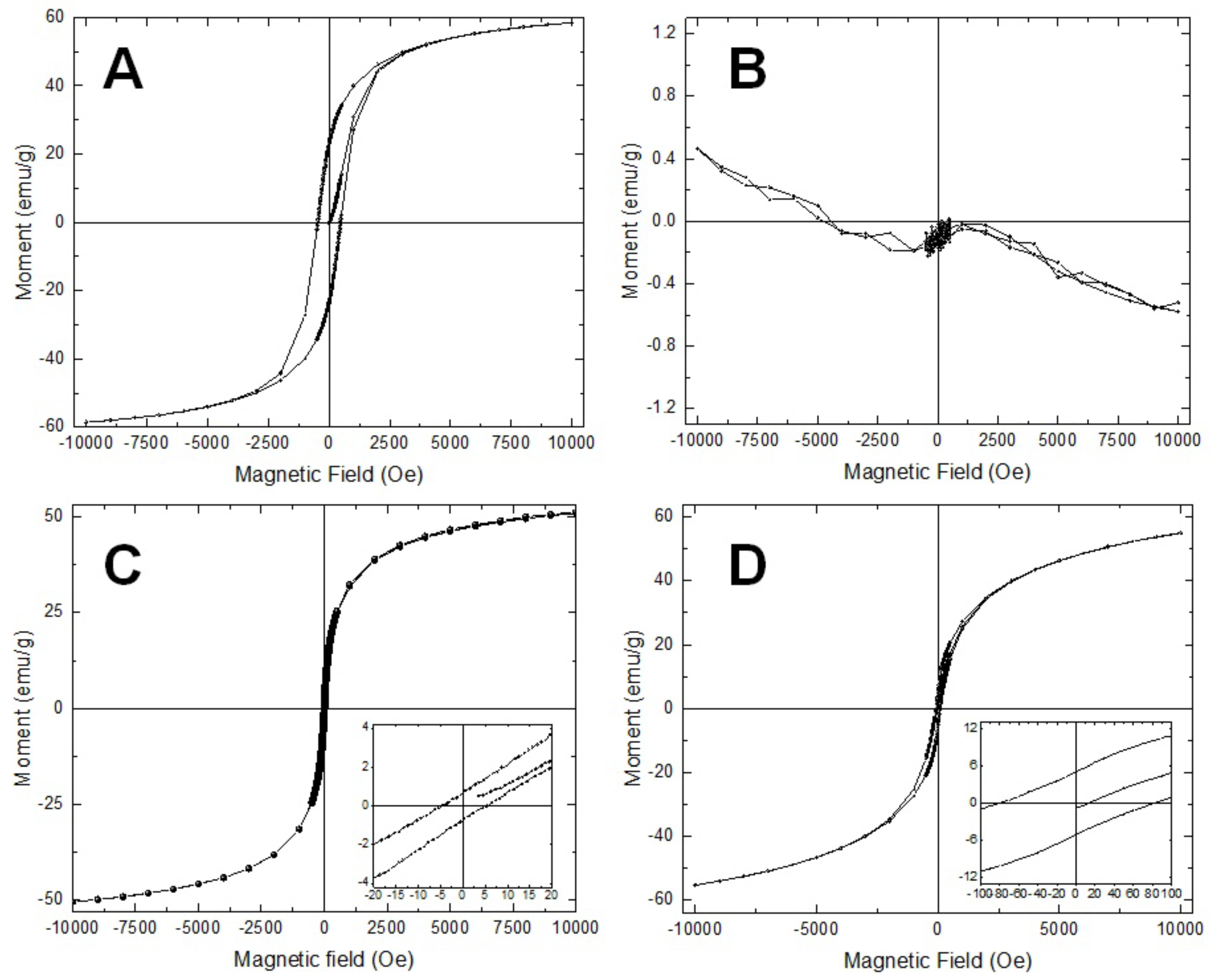

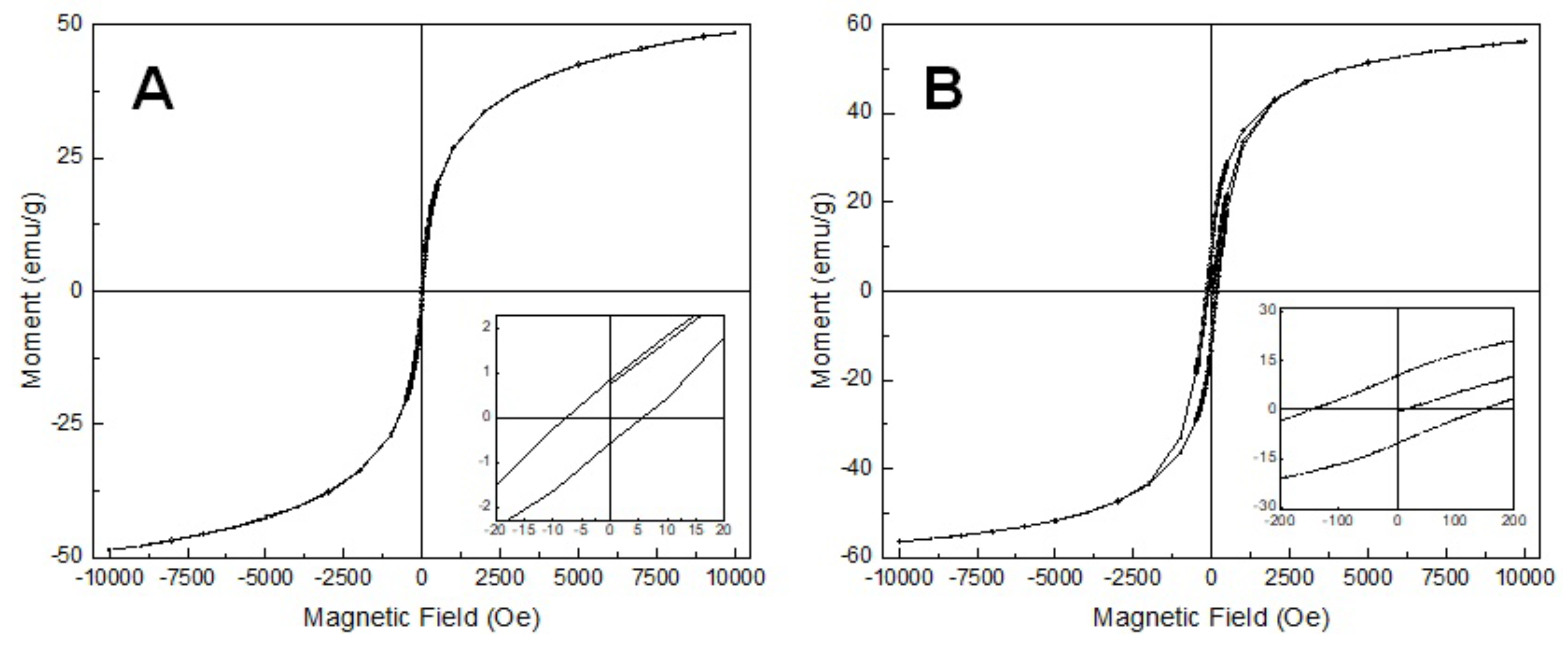

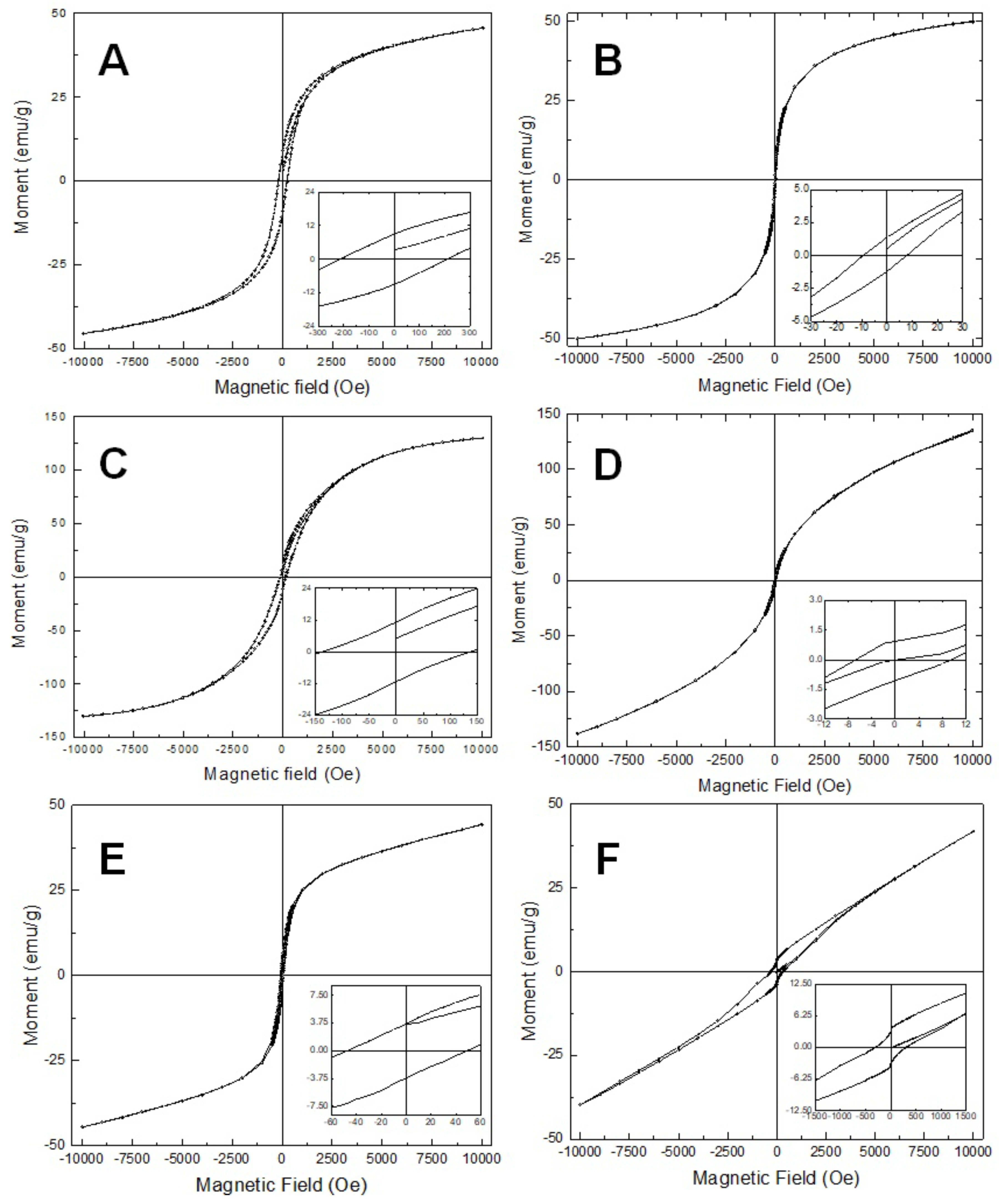

3.3. Magnetic Properties of the Samples

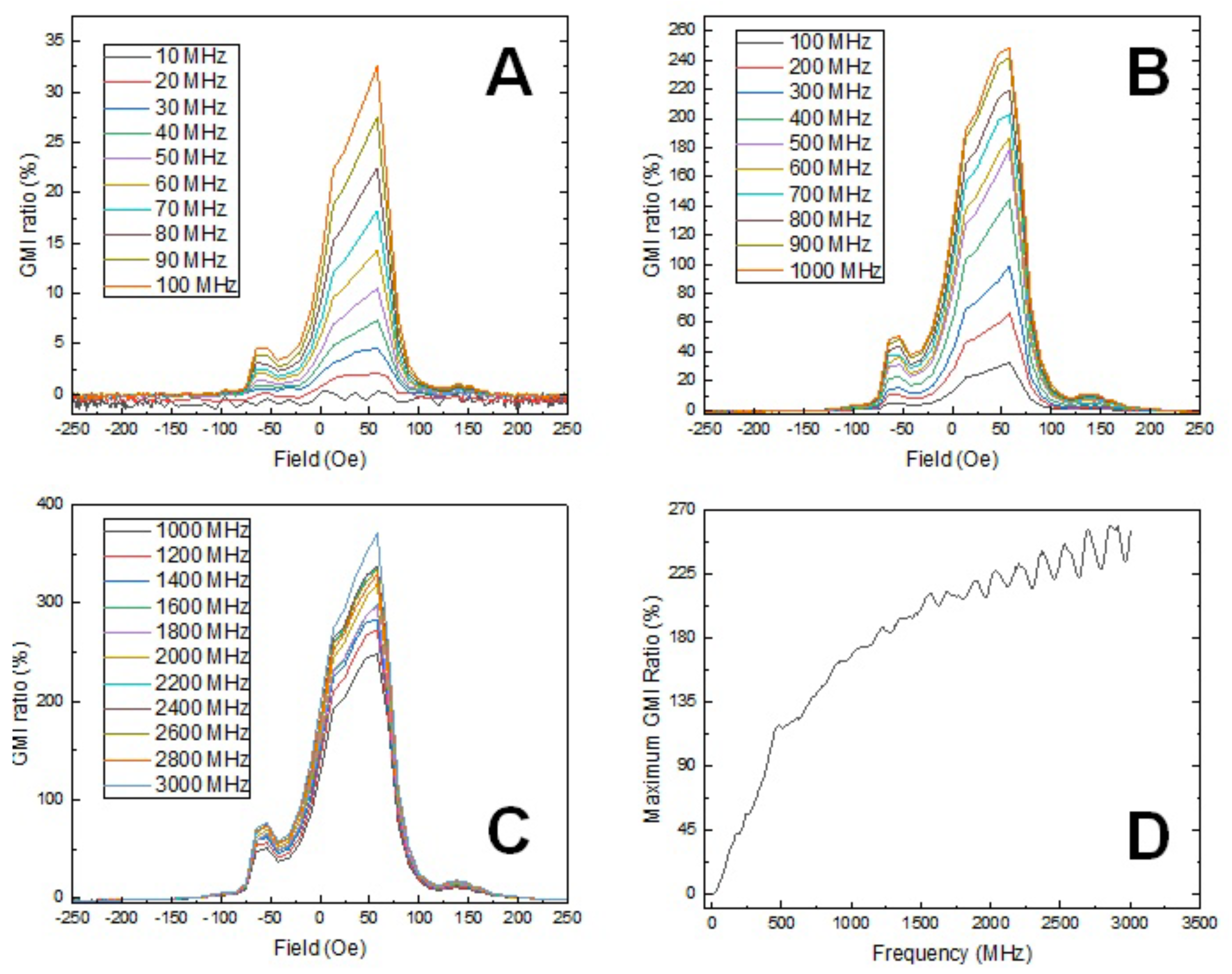

3.4. Magnetic Impedance Measurement of the Coaixal Nanowires

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Jin, S.; Tiefel, T.H.; McCormack, M.; Fastnacht, R.A.; Ramesh, R.; Chen, L.H. Thousandfold change in resistivity in magnetoresistive La-Ca-Mn-O films. Science 1994, 264, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Attfield, J.P. Cation disorder and size effects in magnetoresistive manganese oxide perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, R15622–R15625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, A.P. Colossal magnetoresistance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1997, 9, 8171–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, D.S.; Juang, R.-S. An overview of the structure and magnetism of spinel ferrite nanoparticles and their synthesis in microemulsions. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 129, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.G.; Saion, E.B.; Ahangar, H.A.; Shaari, A.H.; Hashim, M. Simple Synthesis and Characterization of Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles by a Thermal Treatment Method. J. Nanomater. 2010, 2010, 907686. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, D.R.; Chougule, B.K. Effect of copper substitution on electrical and magnetic properties of NiFe2O4 ferrite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 117, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.M.; Yi, J.B.; Yang, Y.; Kho, K.W.; Tan, H.R.; Shen, Z.X.; Ding, J.; Sun, X.W.; Olivo, M.C.; Feng, Y.P. Single-Crystalline MFe2O4 Nanotubes/Nanorings Synthesized by Thermal Transformation Process for Biological Applications. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 2798–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laokul, P.; Arthan, S.; Maensiri, S.; Swatsitang, E. Magnetic and Optical Properties of CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Reverse Micelle Microemulsion Method. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2015, 28, 2483–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, Y.; Alan, F.; Tan, M.; Yilgin, R.; Ozturk, M. Low temperature hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of Mn doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 3625–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhame, S.D.; Joy, P.A. Tuning of the magnetostrictive properties of CoFe2O4 by Mn substitution for Co. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 113911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, Y.; Baykal, A.; Gozuak, F.; Kavas, H. Structural and magnetic properties of CoxZn1-xFe2O4 nanocrystals synthesized by microwave method. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 2887–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapoglu, N.; Birsoz, B.; Baykal, A.; Koseoglu, Y.; Toprak, M.S. Synthesis and magnetic properties of octahedral ferrite NixCo1-x Fe2O4 nanocrystals. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2007, 5, 570–580. [Google Scholar]

- Moradmard, H.; Farjami Shayesteh, S.; Tohidi, P.; Abbas, Z.; Khaleghi, M. Structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of magnesium doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 650, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, Y.W.; Liao, C.S.; Yan, C.H. Magnetism and phase transition for CoFe2-xMnxO4 nanocrystalline thin films and powders. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 247, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.P.; Lee, J.-G.; Kweon, H.S.; Lee, Y.B. The crystallographic, magnetic properties of Al, Ti doped CoFe2O4 powders grown by sol–gel method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2004, 283, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virden, A.; Wells, S.; O’Grady, K. Physical and magnetic properties of highly anisotropic cobalt ferrite particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 316, e768–e771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Sant, S.; Wang, B.; Laurent, S.; Sen, T. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs): development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2011, 63, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Liang, G.; Sun, Q.; Yang, C. High-frequency magnetic properties of Ni-Zn ferrite nanoparticles synthesized by a low temperature chemical method. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 674–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, J.; Lofland, S.E.; Ma, Z.; Mohaddes-Ardabili, L.; Zhao, T.; Salamanca-Riba, L.; Shinde, S.R.; Ogale, S.B.; Bai, F.; et al. Multiferroic BaTiO3-CoFe2O4 Nanostructures. Science 2004, 303, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, G.V.; Groessinger, R. Effect of preparation conditions on magnetoelectric properties of CoFe2O4–BaTiO3 magnetoelectric composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 316, e624–e627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raidongia, K.; Nag, A.; Sundaresan, A.; Rao, C.N.R. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric properties of core-shell CoFe2O4@BaTiO3 nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 062904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Kim, Y.; Goetze, S.; Li, X.; Dong, S.; Werner, P.; Alexe, M.; Hesse, D. Magnetoelectric Coupling in Ordered Arrays of Multilayered Heteroepitaxial BaTiO3/CoFe2O4 Nanodots. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3202–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.J.; Wen, X.; Tiwari, P.; Arnold, D.P.; Andrew, J.S. Magnetic field sensors using arrays of electrospun magnetoelectric Janus nanowires. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2018, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, D.; Bingham, N.S.; Heiligtag, F.J.; Pilet, N.; Warnicke, P.; Vaz, C.A.F.; Shi, Y.; Buzzi, M.; Rupp, J.L.M.; Heyderman, L.J.; et al. Nanoparticle-Based Magnetoelectric BaTiO3–CoFe2O4 Thin Film Heterostructures for Voltage Control of Magnetism. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9840–9851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Dai, J.; Li, Z.; Feng, W. Preparation and magnetic properties of CoFe2O4 oriented fiber arrays by electrospinning. Materials 2020, 13, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallarino, L.; Quintana, M.; Rojo, E.L.; Berger, A. Suppression of Coercivity in Nanoscale Graded Magnetic Materials. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 16, 034038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Chemicals | Molar Ratio | Solvent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoFeO | Co(Ac)4HO | Fe(NO)9HO | 1 | 2 | water | ||

| NiFeO | Ni(Ac)4HO | Fe(NO)9HO | 1 | 2 | water | ||

| FeO | Fe(NO)9HO | - | water | ||||

| BaTiO | Ba(Ac) | Ti(CHO) | 1 | 1 | Propionic acid | ||

| GdBaCuO | Gd(Ac)HO | Ba(Ac) | Cu(Ac) | 1 | 2 | 3 | Propionic acid |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).