Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous Research on the Topic

1.2. The Extreme Characteristics of the 2017 Wildfire Season in Portugal

1.3. The Objective and Hypothesis of This Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Sample

3.2. Firefighters’ Lessons Learned from the 2017 Wildfires

3.2.1. Fire Behavior

- Changes in fire behavior

- Awareness of the 2017 fires repeatability in the future

3.2.2. Fire Exceeding Control Capacity

- Impossible to fight certain fires

3.2.3. Material and Human Resources

- More material and human resources

3.2.4. Defense System Organization

- Governance/Coordination Issues

- Communication in the operational theatre

3.2.5. Strategies and Tactics

- Personal and team safety

- Changes in strategies and tactics

- Limitation in the use of water in direct attack

3.2.6. Preparation

- Firefighters’ preparation

- Firefighters’ endurance

3.2.7. Proactive Initiatives and Actions

- Prevention

- Surveillance

- Increasing penalties

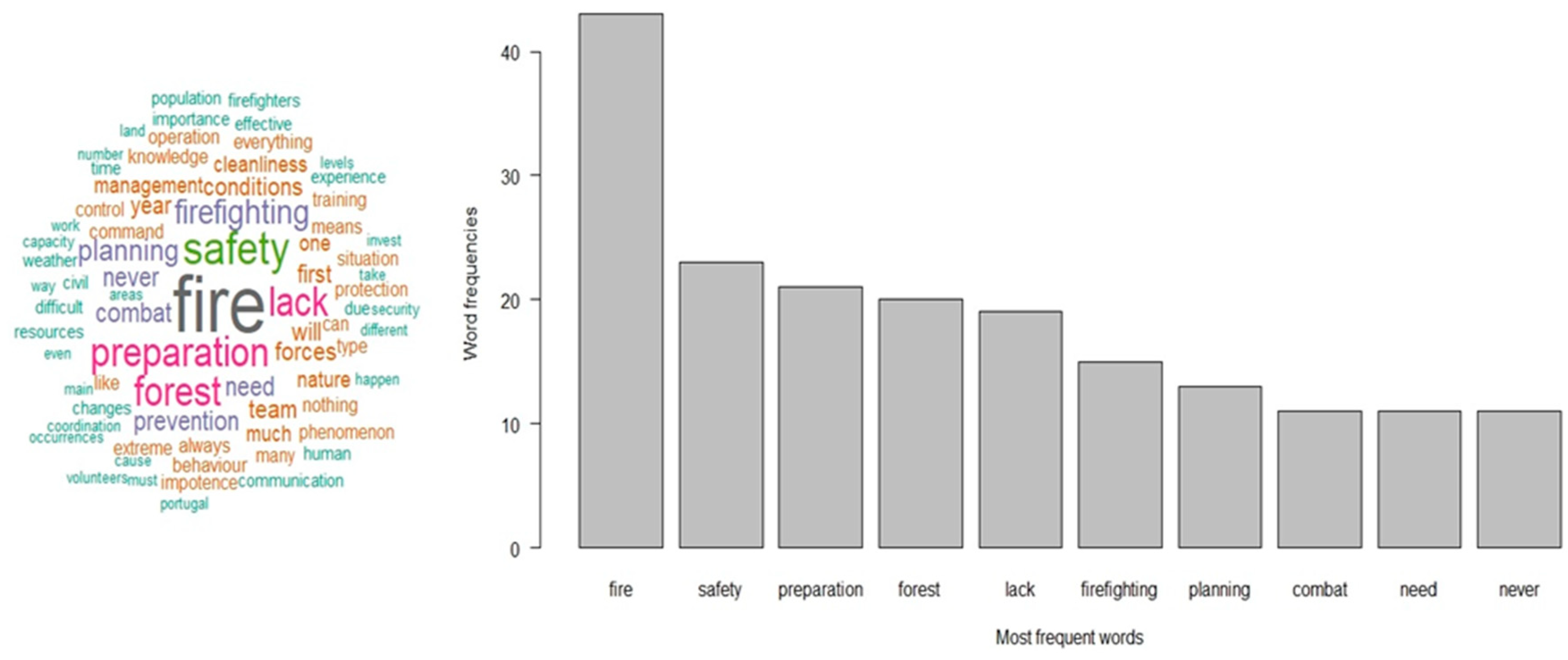

3.2.8. Word Cloud

3.3. Improvement Suggestions

3.3.1. Defense System Organization

- Governance and coordination issues

- Communication in the operational theatre

- Firefighters’ career and work conditions

3.3.2. Preparation

- Firefighters’ preparation

- Citizens’ preparation

3.3.3. Material and Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Supporting and investing in firefighters

- Equipment and vehicles

- Change the financing model

3.3.4. Proactive Initiatives and Actions

- Spatial planning of the territory and forests

- Prevention

3.3.5. Strategies and Tactics

- Personal, teams’, and citizens’ safety

- Changes in strategies and tactics

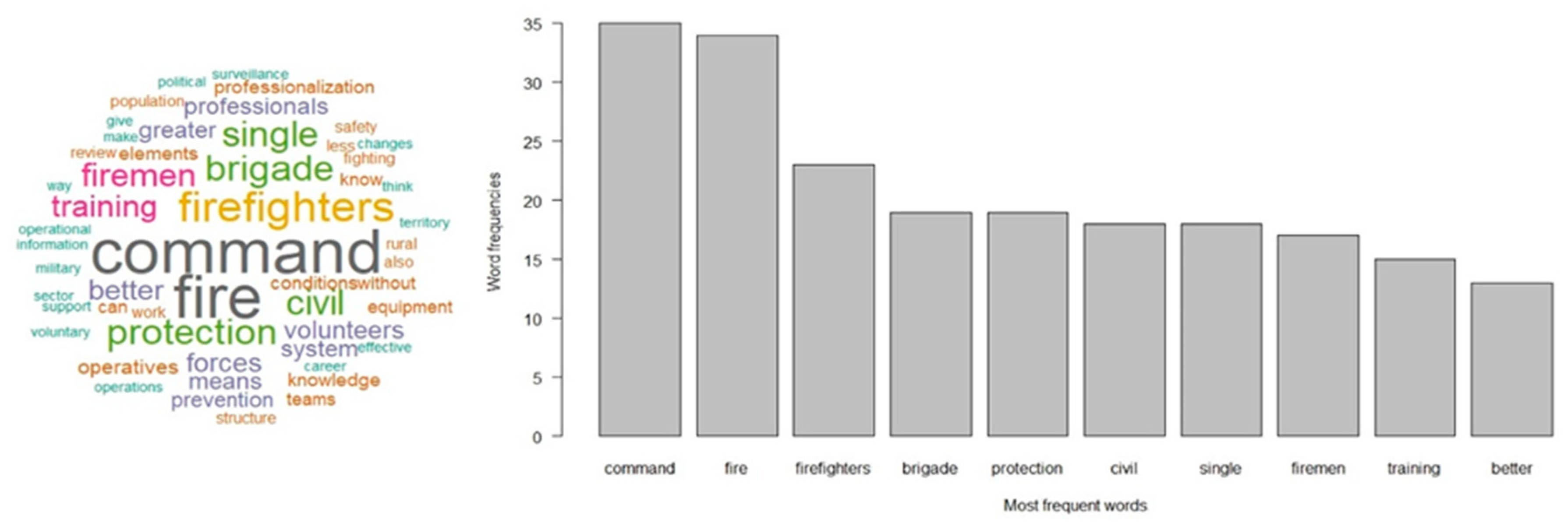

3.3.6. Word Clouds

4. Overall Discussion

4.1. Lessons Learned from the Experience

4.2. Improvement Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leone, V.; Elia, M.; Lovreglio, R.; Correia, F.; Tedim, F. The 2017 Extreme Wildfires Events in Portugal through the Perceptions of Volunteer and Professional Firefighters. Fire 2023, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L.D.; Yocom Kent, L.L.; Sherriff, R.L.; Heyerdahl, E.K. Deciphering the Complexity of Historical Fire Regimes: Diversity Among Forests of Western North America BT - Dendroecology: Tree-Ring Analyses Applied to Ecological Studies. In; Amoroso, M.M., Daniels, L.D., Baker, P.J., Camarero, J.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 185–210. ISBN 978-3-319-61669-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Amraoui, M.; Bouillon, C.; Coughlan, M.; Delogu, G.; Fernandes, P.; Ferreira, C.; McCaffrey, S.; McGee, T.; et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIRE-RES. D1.1 Transfer of Lesson Learned on Extreme Wildfire Events to Key Stakeholders; Castellnou, M., Nebot, E., Estivill, L., Miralles, M., Rosell, M., Valor, T., Casals, P., Eds.; European Union, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, J.; Fonseca, C.; Salgueiro, A.; Fernandes, P.; Lopez, E.; de Neufville, R.; Mateus, F.; Castellnou, M.; Silva, J.S.; Moura, J. Análise e Apuramento Dos Factos Relativos Aos Incêndios Que Ocorreram Em Pedrógão Grande, Castanheira de Pêra, Ansião, Alvaiázere, Figueiró Dos Vinhos, Arganil, Góis, Penela, Pampilhosa Da Serra, Oleiros e Sertã Entre 17 e 24 de Junho de 2017; Lisboa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Técnica, Independente; Guerreiro, J.; Fonseca, C.; Salgueiro, A.; Fernandes, P.; Iglésias, E.; de Neufville, R.; Mateus, F.; Castellno, M.; Sande, J.; et al. Avaliação Dos Incêndios Ocorridos Entre 14 e 16 de Outubro de 2017 Em Portugal Continental; Lisboa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cleave, P. The Pros And Cons Of Using Open Ended Questions. Available online: https://www.smartsurvey.co.uk/blog/the-pros-and-cons-of-using-open-ended-questions# accessed (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Go Survey Open-Ended Questions vs Closed-Ended Questions. Available online: https://www.gosurvey.in/blog/open-ended-questions-vs-closed-ended-questions (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Questback 7 Reasons to Use Open-Ended Survey Questions. Available online: https://www.questback.com/blog/7-reasons-to-use-open-ended-survey-questions/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Dosseto, F. Open-Ended Questions vs. Close-Ended Questions: Examples and How to Survey Users. Available online: https://www.hotjar.com/blog/open-ended-questions/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Kalmukov, Y. Using Word Cloud for Fast Identification of Papers’ Subject Domain and Reviewers Competences. In Proceedings of the Proceedings University of Ruse-2021 volume 60, book 3.2, Studentska, 2021; pp. 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Asare-Marfo, D. Why Do Some Open-Ended Survey Questions Result in Higher Item Nonresponse Rates than Others? Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/decoded/2021/10/14/why-do-some-open-ended-survey-questions-result-in-higher-item-nonresponse-rates-than-others/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- FAO. FAO Strategy on Forest Fire Management; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council Use of Lookouts, Awareness, Communications, Escape Routes, Safety Zones (LACES) System for Safety on the Fireground (AFAC Publication No. 2013); East Melbourne, Vic: Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wotton, B.M.; Flannigan, M.D.; Marshall, G.A. Potential Climate Change Impacts on Fire Intensity and Key Wildfire Suppression Thresholds in Canada. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.P., C.; B., D.; Incoll, R.; Maderson, A. Forest Fire Victoria Inc. Submission to Inspector General for Emergency Management. The Examination of Victoria’s Preparedness, Response, Relief and Recovery Concerning the 2019-20 Fire Season; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, A.; Baker, E.; Kurvits, T. Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires; UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.M. Creating Fire-Smart Forests and Landscapes. Forêt Méditerranéenne 2010, XXXI(4), 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Morgera, E.; Cirelli, M. Forest Fires and the Law: A Guide for National Drafters Based on the Fire Management Voluntary Guidelines.; FAO Legisl.; FAO: Rome, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prestemon, J.; Butry, D.; Chas-Amil, M.; Touza, J. Effects of Law Enforcement Efforts on Intentional Wildfires. In Proceedings of the Advances in forest fire research 2018; Viegas, D., Ed.; University of Coimbra: Coimbra, 2018; p. 1125. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, G. Organograma Das 52 Entidades Que “Controlam Os Incêndios Em Portugal” Tem Fundamento? Não Passa de Uma Extrapolação Grosseira. Available online: https://poligrafo.sapo.pt/fact-check/organograma-das-52-entidades-que-controlam-os-incendios-em-portugal-tem-fundamento-nao-passa-de-uma-extrapolacao-grosseira (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Beighley, M.; Hyde, A.C. Portugal Wildfire Management in a New Era Assessing Fire Risks, Resources and Reforms; Lisbon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rouet-Leduc, J.; Pe’er, G.; Moreira, F.; Bonn, A.; Helmer, W.; Shahsavan Zadeh, S.A.A.; Zizka, A.; van der Plas, F. Effects of Large Herbivores on Fire Regimes and Wildfire Mitigation. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2690–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; McCaffrey, S.; Leone, V.; Delogu, G.M.; Castelnou, M.; McGee, T.K.; Aranha, J. What can we do differently about the extreme wildfire problem: An overview. In Extreme Wildfire Events and Disasters: Root Causes and New Management Strategies; Tedim, F., Leone, V., McGee, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, 2020; pp. 233–263. ISBN 978-0-12-815721-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire Management in Mediterranean-Type Regions: Paradigm Change Needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Davies, G.M.; Ascoli, D.; Fernández, C.; Moreira, F.; Rigolot, E.; Stoof, C.R.; Vega, J.A.; Molina, D. Prescribed Burning in Southern Europe: Developing Fire Management in a Dynamic Landscape. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, e4–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Elliott, G.; Omodei, M. Householder Decision-Making under Imminent Wildfire Threat: Stay and Defend or Leave? Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S.; Wilson, R.; Konar, A. Should I Stay or Should I Go Now? Or Should I Wait and See? Influences on Wildfire Evacuation Decisions. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.K. Preparedness and Experiences of Evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River Wildfire. Fire 2019, Vol. 2, Page 13 2019, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.E.; Cruz, M.G. Fireline Intensity. In Encyclopedia of Wildfires and Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Fires; Manzello, S.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-3-319-51727-8. [Google Scholar]

- Delogu, G.M. Dalla Parte Del Fuoco, Ovvero, Il Paradosso Di Bambi; Il maestrale; 2013; ISBN 9788864291499. [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, S.J. Awful Splendour: A Fire History of Canada; UBC Press: Vancouver, 2011; ISBN 9780774855853. [Google Scholar]

- Carnicer, J.; Alegria, A.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Karali, A.; Koutsias, N.; Lionello, P.; Parrington, M.; Vitolo, C. Global Warming Is Shifting the Relationships between Fire Weather and Realized Fire-Induced CO2 Emissions in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.; Carmo, M.; Rio, J.; Novo, I. Changes in the Seasonality of Fire Activity and Fire Weather in Portugal: Is the Wildfire Season Really Longer? Meteorology 2023, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to Coexist with Wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.L.; Bengston, D.N.; DeVaney, L.A.; Thompson, T.A.C. Wildland Fire Management Futures: Insights from a Foresight Panel; 2015; Vol. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, I.; Nielsen, J.Ø. Coexisting with Wildfire? Achievements and Challenges for a Radical Social-Ecological Transformation in Catalonia (Spain). 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; McCaffrey, S.; Leone, V.; Vazquez-Varela, C.; Depietri, Y.; Buergelt, P.; Lovreglio, R. Supporting a Shift in Wildfire Management from Fighting Fires to Thriving with Fires: The Need for Translational Wildfire Science. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essen, M.; McCaffrey, S.; Abrams, J.; Paveglio, T. Improving Wildfire Management Outcomes: Shifting the Paradigm of Wildfire from Simple to Complex Risk. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2021.2007861 2022, 66, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P.; Spies, T.A.; Steelman, T.A.; Moseley, C.; Johnson, B.R.; Bailey, J.D.; Ager, A.A.; Bourgeron, P.; Charnley, S.; Collins, B.M. Wildfire Risk as a Socioecological Pathology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Forest Fires Sparking Firesmart Policies in the EU; Calzada, V. , Faivre, N., Rego, F., Rodríguez, M., Xanthopoulos, G., Eds.; Publicatio.; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-77492-8. [Google Scholar]

- European Science & Technology Advisory Group (E-STAG) Evolving Risk of Wildfires in Europe. The Changing Nature of Wildfire Risk Calls for a Shift in Policy Focus from Suppression to Prevention; Rossi, J.-L., Komac, B., Migliorin, M., Schwarze, R., Sigmund, Z., Awad, C., Chatelon, F., Goldammerd, J.G., Marcelli, T., Morvan, D., Simeoni, A., Benni, T., Eds.; United Nations for Disaster Risk Reduction: Brussels, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Managing Wildfires in a Changing Climate; Washington DC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Union of European Academies for Science applied to Agriculture. Forest Fires: New Paradigms between Prevention, Management and Recovery; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, C.; Kraus, D.T. Best Practices of Fire Use: Prescribed Burning and Suppression: Fire Programmes in Selected Case-Study Regions in Europe; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Rossa, C.G.; Madrigal, J.; Rigolot, E.; Ascoli, D.; Hernando, C.; Guiomar, N.; Guijarro, M. Prescribed burning in the European Mediterranean Basin. In Global Application of Prescribed Fire; Weir, J., Scasta, D., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 230–248. ISBN 9781486312481. [Google Scholar]

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Xanthopoulos, G. A Wildfire Risk Management Concept Based on a Social-Ecological Approach in the European Union: Fire Smart Territory. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, D.; Plana, E.; Oggioni, S.D.; Tomao, A.; Colonico, M.; Corona, P.; Giannino, F.; Moreno, M.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Kaoukis, K.; et al. Fire-Smart Solutions for Sustainable Wildfire Risk Prevention: Bottom-up Initiatives Meet Top-down Policies under EU Green Deal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 92, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Fire-Smart Management of Forest Landscapes in the Mediterranean Basin under Global Change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, G.M. Dalla Parte Del Fuoco. Ovvero Il Paradosso Di Bambi. Il maestrale, 2013; ISBN 9788864291499. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, A.P.; Claro, J.; Oliveira, T. Simulation Analysis of the Impact of Ignitions, Rekindles, and False Alarms on Forest Fire Suppression. Can. J. For. Res. 2014, 44, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, G.H.; Brown, T.C. Be Careful What You Wish for: The Legacy of Smokey Bear. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.J. Vestal Fire: An Environmental History, Told through Fire, of Europe and Europe’s Encounter with the World; University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 1997; ISBN 0295803525. [Google Scholar]

- P., C.; M., C.; A., L.; M., M.; Kraus, D. Prevention of Large Wildfires Using the Fire Types Concept; Cerdanyola del Vallès: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; ISBN 978-84-694-1457-6. [Google Scholar]

- Castañedaa, N.P.; Reyes, J.B. Cambio climático e incendios de 5a generación. In Natural Hazards & Climate Change, riesgos Naturales y cambio Climático; Santamarta Cerezal, J.C., Hernández-Gutiérrez, L.E., Arraiza Bermudez-Cañete, M.P., Eds.; Colegio de Ingenieros de Montes, 2014; p. 81. ISBN 978-84-617-1060-7. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, V.; Tedim, F. How to create a change in wildfire policies. In Extreme Wildfire Events and Disasters; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Busenberg, G. Wildfire Management in the United States: The Evolution of a Policy Failure. Rev. Policy Res. 2004, 21, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Thompson, M.P.; Finney, M.A. Negative Consequences of Positive Feedbacks in US Wildfire Management. For. Ecosyst. 2015, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.; Dickinson, M.B.; Bohrer, G.; Calkin, D.; Evers, L.; Gilbertson-Day, J.; Nicolet, T.; Ryan, K.; Tague, C. Research and Development Supporting Risk-Based Wildfire Effects Prediction for Fuels and Fire Management: Status and Needs. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2013, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, G.; Leone, V.; Delogu, G.M. The suppression model fragilities: The “firefighting trap.”. In Extreme Wildfire Events and Disasters: Root Causes and New Management Strategies; Tedim, F., Leone, V., McGee, T., Eds.; Elsevier,, 2020; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ekin, A. ‘It eats everything’ – the new breed of wildfire that’s impossible to predict | Horizon: the EU Research & Innovation magazine | European Commission. In Horizon - the EU Research &Innovation Magazine; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Farrel, S. Open-Ended vs. Closed-Ended Questions in User Research. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/open-ended-questions/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

| Firefighters | Original Sample | Replies to Question 1 | Replies to Question 2 | |||

| Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | |

| Professional | 62 | 33.51 | 45 | 36.00 | 34 | 35.05 |

| Volunteers | 123 | 66.49 | 80 | 64.00 | 63 | 64.95 |

| Total | 185 | 100 | 125 | 100.00 | 97 | 100.00 |

| Items | Question 1 | Question 2 | |||||||

| PF | VF | PFS | VF | ||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 38 | 84.4 | 69 | 86.25 | 32 | 94.1 | 55 | 87.3 |

| Female | 7 | 15.6 | 11 | 13.75 | 2 | 5.9 | 7 | 11.11 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.59 | |

| Age | <25 | 2 | 4.4 | 7 | 8.75 | 2 | 5.9 | 3 | 4.76 |

| 25-29 | 4 | 8.9 | 5 | 6.25 | 1 | 2.9 | 5 | 7.94 | |

| 30-34 | 5 | 11.1 | 11 | 13.75 | 3 | 8.8 | 11 | 17.46 | |

| 35-39 | 8 | 17.8 | 9 | 11.25 | 6 | 17.6 | 5 | 7.94 | |

| 40-44 | 10 | 22.2 | 12 | 15 | 9 | 26.5 | 7 | 11.11 | |

| 45-49 | 5 | 11.1 | 16 | 20 | 5 | 14.7 | 14 | 22.22 | |

| 50-54 | 4 | 8.9 | 14 | 17.5 | 3 | 8.8 | 12 | 19.05 | |

| 55-59 | 4 | 8.9 | 6 | 7.5 | 3 | 8.8 | 4 | 6.35 | |

| 60-64 | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 3.75 | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 3.17 | |

| Education level | 2nd cycle (6 years of studies) | 1 | 2.2 | 3 | 3.75 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 1.59 |

| 3rd cycle (9 years of studies) | 5 | 11.1 | 6 | 7.5 | 4 | 11.8 | 4 | 6.35 | |

| Secondary school (12 years of studies) | 29 | 64.4 | 41 | 51.25 | 21 | 61.8 | 35 | 55.56 | |

| Bachelor or license | 7 | 15.6 | 23 | 28.75 | 5 | 14.7 | 18 | 28.57 | |

| Master | 3 | 6.7 | 7 | 8.75 | 3 | 8.8 | 5 | 7.94 | |

| Job starting date | 1973-1990 | 8 | 17.8 | 18 | 22.5 | 6 | 17.6 | 14 | 22.22 |

| 1991-2000 | 17 | 37.8 | 23 | 28.75 | 15 | 44.1 | 19 | 30.16 | |

| 2001 -2010 | 13 | 28.9 | 19 | 23.75 | 9 | 26.5 | 17 | 26.98 | |

| 2011-2021 | 7 | 15.6 | 19 | 23.75 | 4 | 11.8 | 12 | 19.05 | |

| No Response | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.59 | |

| Topics / Items | PF | VF | Total | |||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |||

| Fire behavior | Change in the behavior of fires | 11 | 18.03 | 13 | 13.26 | 24 | 15.09 | |

| Awareness of the 2017 fires repeatability in the future | 1 | 1.64 | 1 | 1.02 | 2 | 1.26 | ||

| Fire exceeding control capacity | Impossible to fight certain fires | 5 | 8.2 | 9 | 9.18 | 14 | 8.81 | |

| Material and human resources | More material and human resources | 5 | 8.2 | 9 | 9.18 | 14 | 8.81 | |

| Defense system organization | Governance/Coordination Issues | 7 | 11.48 | 10 | 10.20 | 17 | 10.69 | |

| Communication in the operational theatre | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4.08 | 4 | 2.52 | ||

| Strategies and tactics | Personal and team safety | 17 | 27.87 | 15 | 16.32 | 32 | 20.13 | |

| Changes in strategies and tactics | 5 | 8.20 | 2 | 2.04 | 7 | 4.40 | ||

| Limitation in the use of water in a direct attack | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.63 | ||

| Preparation | Firefighters’ preparation | 1 | 1.64 | 7 | 7.14 | 8 | 5.03 | |

| Firefighters’ endurance | 1 | 1.64 | 3 | 3.06 | 4 | 2.52 | ||

| Proactive initiatives and actions | Prevention | 4 | 6.5 | 18 | 18.37 | 22 | 13.84 | |

| Surveillance | 1 | 1.64 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.63 | ||

| Increasing penalties | 1 | 1.64 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.63 | ||

| Spatial planning | 3 | 4.92 | 6 | 6.12 | 9 | 5.66 | ||

| Total | 61 | 100 | 98 | 100 | 159 | 100 | ||

| No replies | 17 | 21.79 | 44 | 30.99 | 61 | 43.57 | ||

| Topics / Items/ Subitems | PF | VF | Total | |||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |||

| Material and human resources | Equipment and vehicles | 4 | 7,27 | 6 | 5,66 | 10 | 6,21 | |

| Human resources | 7 | 12,73 | 10 | 9,43 | 17 | 10,6 | ||

| Supporting and investing in firefighters | 3 | 5,45 | 3 | 2,83 | 6 | 3,73 | ||

| Change the financing model | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | ||

| Defense system organization | Governance and coordination issues | Single command to firefighters | 12 | 21,82 | 17 | 16 | 29 | 18 |

| Independence from Civil Protection | 1 | 1,82 | 1 | 0,94 | 2 | 1,24 | ||

| Less politicization of the Civil Protection system | 1 | 1,82 | 2 | 1,89 | 3 | 1,86 | ||

| Better organization | 2 | 3,64 | 3 | 2,83 | 5 | 3,11 | ||

| Concentration of combat in a single entity | 1 | 1,82 | 1 | 0,94 | 2 | 1,24 | ||

| Command of operations | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | ||

| Valorizing experience | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | ||

| Enhanced power and autonomy to operators in the theater of operations | 1 | 1,82 | 2 | 1,89 | 3 | 1,86 | ||

| Collaboration within institutions | 1 | 1,82 | 3 | 2,83 | 4 | 2,48 | ||

| Less bureaucracy and procedures simplification | 0 | 0,00 | 2 | 1,89 | 2 | 1,24 | ||

| Communication in the operational theatre | More information for operators on the field | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | |

| Effective communication system | 1 | 1,82 | 1 | 0,94 | 2 | 1,24 | ||

| Firefighters career and work conditions | Career dignification and remuneration | 2 | 3,64 | 5 | 4.71 | 7 | 4.34 | |

| Better working conditions | 1 | 1,82 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,62 | ||

| Strategies and tactics | Personal and team safety | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | |

| Changes in strategies and tactics | Management of aerial means | 0 | 0,00 | 1 | 0,94 | 1 | 0,62 | |

| Preparation | Firefighters’ preparation | More and rigorous formation, and updated training models | 3 | 5,45 | 7 | 6,6 | 10 | 6,21 |

| Professionalization of firefighters | 4 | 7,27 | 4 | 3,77 | 8 | 4,97 | ||

| Specialization | 3 | 5,45 | 9 | 8,49 | 12 | 7,45 | ||

| Knowledge about fire dynamics | 1 | 1,82 | 3 | 2,83 | 4 | 2,48 | ||

| Citizens ‘preparation | Culture of training the population from school age on | 2 | 3,64 | 3 | 2,83 | 5 | 3,11 | |

| Proactive initiatives and actions | Spatial planning of the territory and forests | 4 | 6.5 | 18 | 18.37 | 22 | 13.84 | |

| Prevention | 1 | 1.64 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.63 | ||

| Do not know/ Does not fit | 1 | 2 | 8 | 7,55 | 9 | 5,59 | ||

| Total | 55 | 100 | 106 | 100 | 161 | 100 | ||

| Rank | Question 1 | Question 2 | ||||

| PF +VF | PF | VF | PF +VF | PF | VF | |

| 1 | Fire | Fire | Fire | Command | Command | Fire |

| 2 | Safety | Forest | Forest | Fire | Fire | Command |

| 3 | Preparation | Lack | Preparation | Firefighting | Brigades | Professional |

| 4 | Forest | Necessary | Lack | Brigades | Civil Protection | Firefighters |

| 5 | Lack | Preparation | Combat | Protection | Firefighters | Volunteers |

| 6 | Firefighting | Behaviour | Fight | Civil Protection | Single | Firemen |

| 7 | Planning | Planning | Prevention | Single | Firefight | Operations |

| 8 | Combat | Safety | Safety | Firemen | Professionals | Knowledge |

| 9 | Need | Security | Forces | Training | Training | Better |

| 10 | Never | Training | Team | Better | Prevention | Civil Protection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).